Abstract

The Brucella abortus type IV secretion system (T4SS), encoded by the virB operon, is essential for establishing persistent infection in the murine reticuloendothelial system. To gain insight into the in vivo interactions mediated by the T4SS, we compared host responses elicited by B. abortus with those of an isogenic mutant in the virB operon. Mice infected with the B. abortus virB mutant elicited smaller increases in serum levels of immunoglobulin G2a, gamma interferon (IFN-γ), and interleukin-12p40 than did mice infected with wild-type B. abortus. Despite equal bacterial loads in the spleen, at 3 to 4 days postinfection, levels of IFN-γ were higher in mice infected with wild-type B. abortus than in mice infected with the virB mutant, as shown by real-time PCR, intracellular cytokine staining, and cytokine levels. IFN-γ-producing CD4+ T cells were more abundant in spleens of mice infected with wild-type B. abortus than in virB mutant-infected mice. Similar numbers of IFN-γ-secreting CD8+ T cells were observed in the spleens of mice infected with B. abortus 2308 or a virB mutant. These results suggest that early differences in cytokine responses contribute to a stronger Th1 polarization of the immune response in mice infected with wild-type B. abortus than in mice infected with the virB mutant.

Brucella abortus is an intracellular pathogen that resides mainly in phagocytic cells and causes disease in animals and humans (3, 43). The infection in both natural and incidental host species is characterized by bacterial persistence in the reticuloendothelial system. This persistent phase of the infection can be studied in the mouse model, which has been used to identify virulence mechanisms used by Brucella spp. to establish persistence (15, 17, 22, 31, 32).

Protection against B. abortus infection is thought to be mediated primarily by a Th1 type of immune response (1, 44). B. abortus triggers host antigen-presenting cells to release interleukin-12 (IL-12), which causes Th0 cells to differentiate into gamma interferon (IFN-γ)-secreting Th1 cells that are capable of activating macrophage microbicidal mechanisms (25, 44). In vitro and in vivo studies using mouse or murine macrophages have shown that infection with Brucella spp. triggers the production of IL-6, IL-1, and tumor necrosis alpha, whereas in humans, IL-1, IL-6, and IL-8, but not tumor necrosis alpha, are produced during infection (5, 11, 28). While IFN-γ and IL-12 promote the control of Brucella replication in the mouse, IL-10 decreases the ability of mice to control infections with B. abortus (12, 33).

The type IV secretion system (T4SS) encoded by the virB operon is essential for establishing persistent infection by Brucella spp. in mice (10, 17, 35, 38). In addition, it has been shown to contribute to intracellular survival in in vitro models of infection by allowing the vacuole containing Brucella spp. to exclude lysosomal proteins and associate with the exit sites of the endoplasmic reticulum (6-9). This endoplasmic reticulum-associated compartment appears to be the preferred niche for the intracellular replication of Brucella spp. Although it is widely thought that the formation of the replicative niche for Brucella requires the translocation of effector proteins into the host cell that interfere with vacuolar trafficking, no secreted effectors of the T4SS have been identified to date.

Our knowledge about how Brucella spp. persist in the host in the face of an active immune response to the bacteria is limited. In particular, the relationship between T4SS-mediated intracellular survival and replication in vitro and persistence in the reticuloendothelial system in vivo is unclear. B. abortus mutants lacking an intact T4SS are initially able to colonize the spleens of mice during the first 3 days after infection at the same levels as those of wild-type bacteria (31, 32). Furthermore, while B. abortus infection results in the early activation of host genes involved in inflammation and immunity, mutants lacking a functional T4SS do not trigger this response (32). To gain further insight into how the T4SS affects the host response to infection, we characterized serum antibody and cytokine responses to B. abortus 2308, a wild-type strain, and an isogenic virB mutant. The results of these studies showed that while infection with wild-type B. abortus elicits a Th1 type of immune response, this polarization is decreased in mice infected with a mutant lacking a functional T4SS.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, media, and culture conditions.

Bacterial strains used in this study were Brucella abortus wild-type strain 2308 and its isogenic mutant strain BA41 (17), which has an insertion of mTn5Km2 at nucleotide 1232 of the B. abortus virB locus (GenBank accession number AF226278). This insertion is located 59 bp downstream of the virB1 gene and is polar upon the expression of downstream genes in the virB operon (39). Strains were cultured on tryptic soy agar (Difco/Becton-Dickinson, Sparks, MD) or in tryptic soy broth at 37°C on a rotary shaker. Bacterial inocula for infection of mice were cultured on tryptic soy agar plus 5% blood (2). For cultures of strain BA41, kanamycin (Km) was added to the culture medium at 100 mg/liter. All work with live B. abortus cells was performed at biosafety level 3.

Infection of mice.

Female C57BL/6 mice were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME) and were used at the age of 6 to 8 weeks. Mice were held in microisolator cages with sterile bedding and water and irradiated feed in a biosafety level 3 facility. Groups of 5 to 10 mice were inoculated intraperitoneally (i.p.) with 0.1 ml of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 5 × 105 cells of a B. abortus wild-type strain or an isogenic virB mutant. All animal experiments were approved by the Texas A&M University and University of California Laboratory Animal Care and Use Committees and were conducted in accordance with institutional guidelines.

Multiplex cytokine assays.

Detection of specific cytokines in the serum or spleens of C57BL/6 mice was performed using Multi-Plex cytokine assays (4) (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Groups of five C57BL/6 mice were infected i.p. with 5 × 105 cells of either the wild type or the virB mutant, and serum was obtained from the saphenous vein at days 1, 4, and 7 postinfection. Cytokine detection was performed according to the instructions provided by the kit's manufacturer. Briefly, serum was filtered twice through a 0.2-μm filter and then diluted 1:3 in Multi-Plex sample diluent buffer, added to the plate, and incubated at room temperature for 30 min. The samples were washed several times, and 25 μl of the detection antibody solution was added to each well. Washes were monitored by incubation at room temperature for 30 min. The samples were washed, and 50 μl of streptavidin-phycoerythrin was added and incubated at room temperature for 10 min. The samples were washed and resuspended in 125 μl of assay buffer (proprietary formula) and read using the Luminex 100 instrument (Bio-Rad).

For the detection of specific cytokines in the spleen, groups of five C57BL/6 mice were infected i.p. with 5 × 105 cells of either wild-type or virB mutant B. abortus, and spleens were obtained at days 1, 4, and 7 postinfection. Spleens were homogenized in 3 ml of PBS and passed through a 100-μm cell strainer. The cells were centrifuged for 10 min at 1,000 rpm. The supernatant was passed twice through a 0.2-mm filter and cultured to ensure that no viable bacteria were present. Cytokines were concentrated by using Millipore 5K filter devices and stored at −80°C. Cytokine detection was performed as described above.

ELISA.

The presence of antibody specific for Brucella abortus in the serum samples from 10 C57BL/6 mice infected with B. abortus 2308 and 10 mice infected with the B. abortus virB mutant was determined by indirect enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). MaxiSorp plates from Qiagen (Valencia, CA) were coated with 100 μl formalin-killed whole B. abortus cells (1 μg/ml) in carbonate buffer (pH 9.6), and plates were incubated at 4°C overnight. After washing with PBS and 0.05% Tween 20, the serum samples were diluted 1:100 in PBS containing 1% bovine serum albumin and incubated at room temperature for 1 h. After washing with PBS and 0.05% Tween 20, the reactivity was measured using horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse immunoglobulin M (IgM), IgG, IgG1, IgG2a, or IgG3 (1:1,000; BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA) by incubating the plates at 37°C for 1 h. The reaction was developed with Sigma Fast o-phenylenediamine dihydrochloride tablet sets. The resulting color was read at 410 nm with an ELISA microplate reader (MR5000; Dynatech). Data points are the averages of duplicate dilutions, with each measurement being performed twice.

RNA isolation.

RNA was isolated using Tri reagent (Molecular Research Centre, Inc., Cincinnati, OH). Spleen samples were homogenized in 1 ml of Tri reagent and incubated for 5 min at room temperature. RNA was extracted by adding 0.2 ml of chloroform and centrifuging the samples at 10,000 rpm for 15 min at 4°C. RNA was precipitated with 0.5 ml of isopropanol and resuspended in H2O.

cDNA.

One microgram of RNA was transcribed to cDNA using TaqMan reverse transcription reagents (Applied Biosystems, Branchburg, NJ). The RNA was mixed with a solution containing 5 μl of 10× buffer, 11 μl of 20 mM MgCl2, 10 μl of deoxynucleoside triphosphates, 2.5 μl of random hexamers, 1 μl of reverse transcriptase, and H2O in a final volume of 50 μl. Samples were incubated at 25°C for 10 min, followed by reverse transcription at 48°C for 30 min and inactivation at 95°C for 5 min.

Real-time PCR.

Reverse-transcribed cDNA was amplified with previously reported primer sets (26) for mouse IFN-γ (forward primer TCA AGT GGC ATA GAT GTG GAA GAA and reverse primer TGG CTC TGC AGG ATT TTC ATG) and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) (forward primer TGT AGA CCA TGT AGT TGA GGT CA and reverse primer AGG TCG GTG TGA ACG GAT TTG) using Sybr green PCR master mix (Applied Biosystems) and an ABI Prism 7900HT detection system (Applied Biosystems) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Induction of mRNA was determined from the threshold cycle (CT) values normalized for GAPDH expression and then normalized to the value derived from the naive controls (23).

Intracellular cytokine staining.

Intracellular staining for IFN-γ was performed in splenocytes from groups of four C57BL/6 mice infected for 3 days with B. abortus 2308 or a virB mutant. Splenocytes from each mouse were analyzed individually using four-color flow cytometry. Briefly, after passing the spleen cells through a 100-μm cell strainer and treating the samples with ACK buffer (0.15 M NH4Cl, 1.0 mM KHCO3, 0.1 mM Na2EDTA [pH 7.2]) to lyse red blood cells, splenocytes were washed with PBS (Gibco) containing 1% bovine serum albumin (fluorescence-activated cell sorter [FACS] buffer). Cells were incubated for 6 h in RPMI 1640-5% fetal bovine serum with 10 μg/ml brefeldin A (Sigma). Cells were stained individually or with a cocktail of Pacific Blue-conjugated rat anti-mouse CD4 (L3T4), Alexa Fluor 700-conjugated rat anti-mouse CD8a (Ly-2), and allophycocyanin II-Alexa Fluor 750 rat anti-mouse CD3e (eBioscience). The cells were washed with FACS buffer and fixed with 4% formaldehyde for 30 min at 4°C, followed by permeabilization for 30 min using a saponin-based buffer and staining with phycoerythrin-conjugated anti-mouse IFN-γ for 30 min at 4°C. Finally, samples were washed in FACS buffer containing saponin. Flow cytometry analysis was performed using an LSRII apparatus (Becton Dickinson, San Diego, CA), and data were collected for over 1 million cells/mouse. The CD3 cells were gated (R1) based on side scatter and CD3 expression. CD4+ or CD8+ T cells were gated (R2) based on CD3 expression and CD4 or CD8 expression, respectively.

Statistical analysis.

For the determination of statistical significance between experimental groups, a Student's t test was performed on the data after logarithmic conversion. A P value of <0.05 was considered to be significant.

RESULTS

The T4SS mutant and the wild type elicit different antibody responses in infected mice.

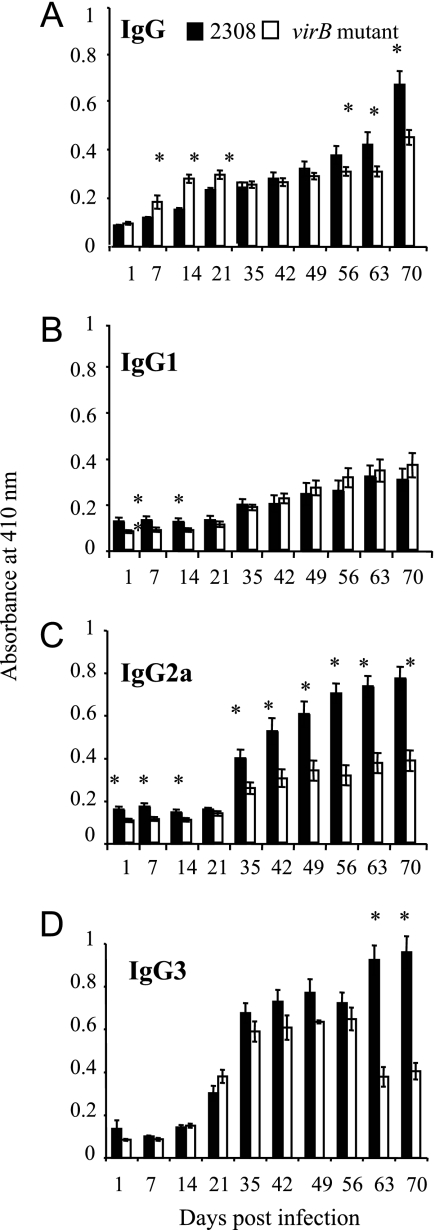

To compare host responses to wild-type B. abortus and a virB mutant, anti-B. abortus IgG levels in serum from infected mice were measured by ELISA. The results of this experiment (Fig. 1A) revealed that between days 7 and 21, the virB mutant elicited a higher B. abortus-specific IgG response than strain 2308, while after day 56, mice infected with wild-type B. abortus exhibited higher IgG titers. This trend was also observed when IgM was assayed in the same serum samples (data not shown). The differences in titer early during infection may reflect increased killing and presentation of antigen from the virB mutant, which started to be cleared from spleens of infected mice by 5 days after infection, while CFU of the wild-type strain did not decline (31). To determine whether these IgG responses are qualitatively similar, we assayed the same serum samples for IgG1, IgG2a, and IgG3 isotypes. Both strains elicited similar levels of IgG1 (Fig. 1B) and IgG3 (Fig. 1D), but levels of IgG2a (Fig. 1C) were significantly higher in mice infected with B. abortus 2308 between 35 and 70 days postinfection. In an identical experiment performed using BALB/c mice (data not shown), we obtained the same results, showing that this difference is not related to differences between the two mouse strains in their responses to Brucella infection (25).

FIG. 1.

Measurement of antibody levels in sera from mice infected with B. abortus 2308 or the virB mutant by ELISA. Samples from groups of 10 mice inoculated i.p. with 5 × 105 cells of either B. abortus 2308 or the virB mutant were taken at different times postinoculation. The significance of differences between arithmetic means of data for wild-type and mutant mice at each time point was determined using a Student's t test. Asterisks indicate significant differences between immunoglobulin levels in mice infected with 2308 and those in mice infected with the virB mutant (P < 0.05).

The virB mutant elicits reduced levels of circulating IFN-γ and IL-12 in comparison with those of wild-type B. abortus.

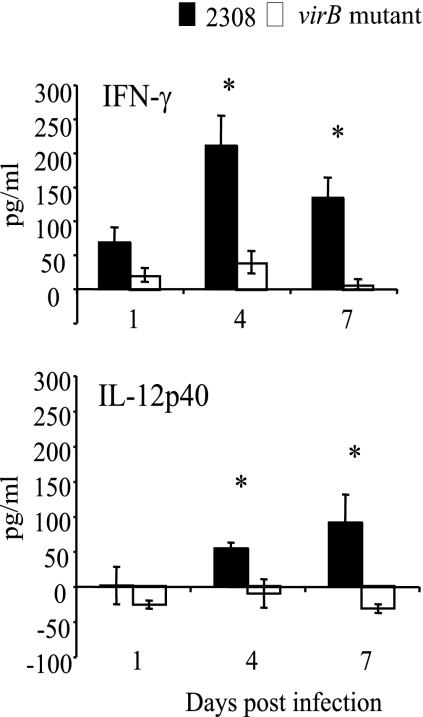

In order to determine whether the higher levels of IgG2a elicited by wild-type B. abortus reflected a greater Th1 polarization of the early immune response, we determined the levels of the Th1-associated cytokines IFN-γ and IL-12 after infection with wild-type B. abortus or the virB mutant. For these experiments, mice were infected with either wild-type B. abortus or the virB mutant, and serum was obtained at days 1, 4, and 7 postinfection. The detection of IFN-γ and IL-12p40 was performed using BioPlex cytokine assays (Fig. 2). Since the cytokine levels in naive serum varied among mice, the increase in the cytokine concentration in infected serum samples over that in uninfected serum samples was calculated (Fig. 2). Results of the cytokine assays showed that on days 4 and 7 postinfection, levels of IFN-γ and IL-12p40 remained unchanged in the sera of mice infected with B. abortus virB, whereas in mice infected with the B. abortus wild-type strain, the levels of IL-12p40 and IFN-γ increased significantly above preinfection levels.

FIG. 2.

Quantification of cytokine levels in sera of mice infected with B. abortus 2308 or the virB mutant. Samples from groups of 10 mice infected i.p. with either B. abortus 2308 or the virB mutant were taken at different times postinoculation, and cytokine concentrations were determined by Multi-Plex assays. Data shown are increases in cytokine concentrations over preinfection levels. The significance of differences for wild-type and mutant mice at each time point was determined using a paired Student's t test. Error bars represent standard deviations. Asterisks indicate significant differences between the wild type and the mutant (P < 0.05).

Splenocytes of mice infected with the Brucella wild-type strain produce higher levels of IFN-γ than do splenocytes of mice infected with the T4SS mutant.

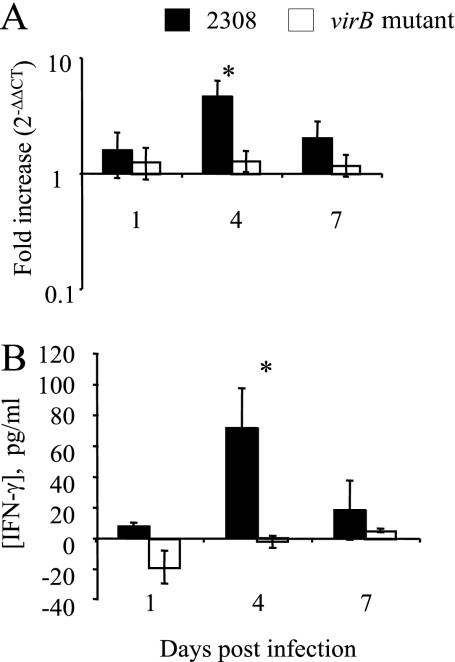

Since B. abortus grows and persists in tissues of the reticuloendothelial system, we determined whether the difference in the level of circulating IFN-γ correlates with changes in IFN-γ production in splenic tissue when the CFU levels of 2308 and the virB mutant are similar. RNA from spleens isolated from mice infected with B. abortus 2308 or the virB mutant was used to quantify IFN-γ transcripts by quantitative real-time PCR. The results shown in Fig. 3A are normalized to levels of GAPDH and to levels in uninfected mice using the 2−ΔΔCT formula. Figure 3B (bottom) shows increases in IFN-γ protein levels measured by a BioPlex assay in concentrated supernatants of spleen homogenates. Significantly greater increases in both IFN-γ transcripts and protein levels were observed at day 4 postinfection in mice infected with B. abortus 2308 than in mice infected with the virB mutant, which is in agreement with the levels of IFN-γ measured in the serum (Fig. 2).

FIG. 3.

Quantification of IFN-γ levels in spleens of mice infected with B. abortus 2308 or the virB mutant. (A) Transcript levels in spleens from groups of five mice infected with either B. abortus 2308 (black bars) or the virB mutant (white bars) were assayed by real-time reverse transcription-PCR at different times postinoculation. Increases (2−ΔΔCT) in transcript levels were calculated by normalizing CT values for IFN-γ levels to CT values for GAPDH levels and to CT values for IFN-γ levels measured in a group of mock-infected mice. (B) Cytokine measurement of IFN-γ in splenic tissue by Multi-Plex assay was performed with groups of five mice infected with either B. abortus 2308 or the virB mutant at different times postinoculation. Data shown are increases in cytokine concentrations over preinfection levels. The significance of differences for wild-type and mutant mice at each time point was determined using a paired Student's t test. Error bars represent standard deviations. Asterisks indicate significant differences between the wild type and the mutant (P < 0.05). Results shown at the top and bottom are from two independent experiments.

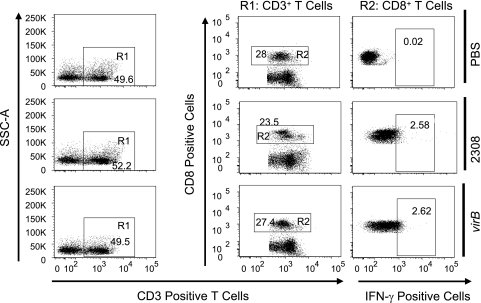

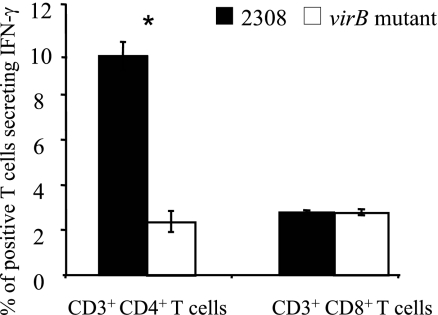

Splenic CD4+ T cells, but not CD8+ T cells, produce more IFN-γ when mice are infected with wild-type B. abortus than when they are infected with the virB mutant.

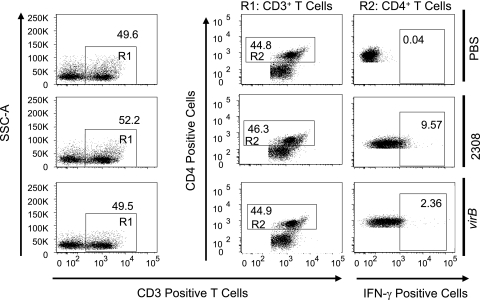

We decided to determine the main source of IFN-γ in splenic T cells after infection with wild-type Brucella or the virB mutant (Fig. 4 and 5). Three days after infection, when the bacterial burdens of wild-type B. abortus and the virB mutant were similar (31, 32; data not shown), mice infected with wild-type B. abortus had more numerous IFN-γ-producing CD4+ T cells (9.7% ± 0.6%) than did virB mutant-infected mice (2.3% ± 0.5%) (Fig. 6). However, no difference in the frequencies of IFN-γ-producing CD8+ T cells in wild-type and mutant-infected mice was observed (2.7% ± 0.6% for 2308 and 2.6% ± 0.5% for the virB mutant) (Fig. 6). This result shows that CD4+ T cells are the source of increased levels of IFN-γ elicited by B. abortus and that infection with the virB mutant elicits reduced IFN-γ production by splenic CD4+ T cells.

FIG. 4.

IFN-γ-producing CD4+ T cells in spleens of mice after infection with B. abortus 2308 or the virB mutant. C57BL/6 mice (four mice per group) were injected i.p. with PBS or 5 × 105 CFU of B. abortus 2308 or the virB mutant. Mice were sacrificed 3 days after infection, and splenocytes were stained with a cocktail of Pacific Blue-conjugated anti-mouse CD4 (L3T4), Alexa Fluor 700-conjugated anti-mouse CD8a (Ly-2), APC-Alexa Fluor 750 anti-mouse CD3e, and phycoerythrin-conjugated anti-mouse IFN-γ. One million cells/sample were acquired with an LSRII apparatus. Numbers indicate the percentages of cells in each gate. Data for one mouse per group are shown as a representative of the group. SSC, side scatter.

FIG. 5.

IFN-γ-producing CD8+ T cells in spleens of mice after infection with B. abortus 2308 or the virB mutant. C57BL/6 mice (four mice per group) were injected i.p. with PBS or 5 × 105 CFU of B. abortus 2308 or the virB mutant and sacrificed 3 days after infection. Splenocytes were stained as described in the legend of Fig. 4. One million cells/sample were acquired with an LSRII apparatus. Numbers indicate the percentages of cells in each gate. Data for one mouse per group are shown as a representative of the group. SSC, side scatter.

FIG. 6.

Percentage of splenic CD4+ T cells or CD8+ T cells secreting IFN-γ after infection with B. abortus 2308 or the virB mutant. C57BL/6 mice (four mice per group) were injected i.p. with PBS or 5 × 105 CFU of B. abortus 2308 or the virB mutant. Mice were sacrificed 3 days after infection, and cells/mouse were stained for IFN-γ-producing cells. One million cells/sample were acquired with an LSRII apparatus. The asterisk represents statistical significance determined using a Student's t test on data after logarithmic conversion.

DISCUSSION

This study was undertaken to investigate the in vivo effects of the B. abortus T4SS on the host response to infection. We showed previously that during the infection of mice with B. abortus wild-type isolate 2308 and its isogenic virB mutant, both strains are present in similar numbers for the first 5 days postinfection (31). By 5 days postinfection, colonization of the spleen by the T4SS mutant starts to decrease relative to that of the wild-type, which persists at a constant level (31). The finding that both the virB mutant and the wild type are initially able to colonize the spleen at similar levels following i.p. inoculation suggests that during the first few days after infection, the virB mutant is able to resist immune clearance as well as does wild-type B. abortus. However, despite equal survival rates in tissues during this early period (3 to 4 days) after infection, wild-type B. abortus and virB mutant B. abortus elicited very different transcriptional responses in host splenocytes. While infection with wild-type B. abortus resulted in the upregulation of genes involved in inflammation and immunity, including IFN-γ and genes induced by both IFN-γ and IFN-α/β, the virB mutant used in the present study did not (32). To determine whether these differences in early host transcriptional responses in the spleen correlate with differences in global immune responses to both Brucella strains, we examined serum antibody and cytokine responses to wild-type B. abortus and the T4SS mutant.

In line with previous reports, infection with wild-type B. abortus preferentially elicited IgG2a, which is indicative of a Th1-type response (41). Interestingly, the increase in the level of IgG2a in sera of mice infected with the virB mutant over levels in sera of uninfected mice was only modest (Fig. 1). There are two possible explanations for this difference: one is a lack of antigen to stimulate the immune response in mice infected with the virB mutant, as by 56 days, very few of the virB mutant bacteria remained in the spleen (17, 31). Alternatively, wild-type B. abortus and the virB mutant could elicit different responses early during infection that could influence later development of different antibody isotype profiles. To test the second idea, we compared serum cytokine profiles elicited by infection with B. abortus 2308 and those elicited by infection with the virB mutant at 3 to 4 days postinfection, when similar numbers of both strains were present in the spleen (31). In agreement with previously published reports (13, 14, 37, 44), the levels of IL-12p40 and IFN-γ increased significantly above preinfection levels in mice infected with wild-type B. abortus. The virB mutant did not elicit IL-12 production, which is required for the stimulation of IFN-γ production and Th1 polarization (19), and also did not elicit IFN-γ production. We did not detect increases in serum levels of IL-4 (not shown), which would be indicative of Th2 polarization (40), in mice infected with either B. abortus strain. The weak Th1 polarization elicited by the virB mutant may contribute to its reduced protective properties as a vaccine compared with other attenuated strains of Brucella spp. (20, 21).

The cytokines present during T-cell responses influence the differentiation of Th cells into Th1 cells, which produce IFN-γ and IL-2, thereby stimulating cell-mediated responses, or Th2 cells, which produce IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, and IL-10 and mediate humoral responses. Although differences in methodology make it difficult to compare these results with those from previously published studies, the trend that we observed is in line with previous reports in which cytokine production could be elicited in splenocytes from B. abortus-infected mice by ex vivo stimulation with B. abortus antigens (18, 25, 27).

Effectors secreted by the T4SS play important roles in the interaction of bacterial pathogens with their hosts, and a number of them interfere with the immune response to infection (16, 30, 34, 36, 42). Furthermore, in Helicobacter pylori and Legionella pneumophila, there is evidence for the T4SS-mediated release of peptidoglycan (42) and flagellin (24, 29), respectively, into infected cells, and therefore, the T4SS-dependent induction of IFN-γ and IL-12 could result from either the injection of effectors or the release of pathogen-associated molecular patterns into the host cell cytosol. Once type IV secreted Brucella molecules have been identified, it will be possible to determine whether they act directly or indirectly to trigger the T4SS-dependent host responses observed in this study. In summary, results presented here suggest that the T4SS is required to elicit early differences in cytokine responses to wild-type B. abortus and the virB mutant that contribute to the Th1 polarization of the immune response.

Acknowledgments

This investigation was conducted in a facility constructed with support from Research Facilities Improvement Program grant C06 RR12088-01 from the National Center for Research Resources, National Institutes of Health. Work in the laboratory of R.M.T. is funded by NIH grants AI50553 and U54 AI057156.

We thank L. Sower and A. Recinos III for assistance with use of the BioPlex Instrument in the WRCE Proteomics Facility. We are also grateful to A. Bäumler and N. Baumgarth for critical comments on the manuscript.

Editor: J. B. Bliska

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 5 May 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Agranovich, I., D. E. Scott, D. Terle, K. Lee, and B. Golding. 1999. Down-regulation of Th2 responses by Brucella abortus, a strong Th1 stimulus, correlates with alterations in the B7.2-CD28 pathway. Infect. Immun. 674418-4426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alton, G. G., L. M. Jones, and D. E. Pietz. 1975. Laboratory techniques in brucellosis. Monogr. Ser. World Health Organ. 1-163. [PubMed]

- 3.Araj, G. F. 1999. Human brucellosis: a classical infectious disease with persistent diagnostic challenges. Clin. Lab. Sci. 12207-212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Branden, L. J., and C. I Smith. 2002. Bioplex technology: novel synthetic gene delivery system based on peptides anchored to nucleic acids. Methods Enzymol. 346106-124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Caron, E., T. Peyrard, S. Kohler, S. Cabane, J. P. Liautard, and J. Dornand. 1994. Live Brucella spp. fail to induce tumor necrosis factor alpha excretion upon infection of U937-derived phagocytes. Infect. Immun. 625267-5274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Celli, J., C. de Chastellier, D. M. Franchini, J. Pizarro-Cerda, E. Moreno, and J. P. Gorvel. 2003. Brucella evades macrophage killing via VirB-dependent sustained interactions with the endoplasmic reticulum. J. Exp. Med. 198545-556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Celli, J., S. P. Salcedo, and J. P. Gorvel. 2005. Brucella coopts the small GTPase Sar1 for intracellular replication. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1021673-1678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Comerci, D. J., M. J. Martinez-Lorenzo, R. Sieira, J. P. Gorvel, and R. A. Ugalde. 2001. Essential role of the VirB machinery in the maturation of the Brucella abortus-containing vacuole. Cell. Microbiol. 3159-168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Delrue, R. M., M. Martinez-Lorenzo, P. Lestrate, I. Danese, V. Bielarz, P. Mertens, X. De Bolle, A. Tibor, J. P. Gorvel, and J. J. Letesson. 2001. Identification of Brucella spp. genes involved in intracellular trafficking. Cell. Microbiol. 3487-497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.den Hartigh, A. B., Y. H. Sun, D. Sondervan, N. Heuvelmans, M. O. Reinders, T. A. Ficht, and R. M. Tsolis. 2004. Differential requirements for VirB1 and VirB2 during Brucella abortus infection. Infect. Immun. 725143-5149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dornand, J., A. Gross, V. Lafont, J. Liautard, J. Oliaro, and J. P. Liautard. 2002. The innate immune response against Brucella in humans. Vet. Microbiol. 90383-394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fernandes, D. M., and C. L. Baldwin. 1995. Interleukin-10 downregulates protective immunity to Brucella abortus. Infect. Immun. 631130-1133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fernandez-Lago, L., M. Monte, and A. Chordi. 1996. Endogenous gamma interferon and interleukin-10 in Brucella abortus 2308 infection in mice. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 15109-114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fernandez-Lago, L., E. Rodriguez-Tarazona, and N. Vizcaino. 1999. Differential secretion of interleukin-12 (IL-12) subunits and heterodimeric IL-12p70 protein by CD-1 mice and murine macrophages in response to intracellular infection by Brucella abortus. J. Med. Microbiol. 481065-1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fretin, D., A. Fauconnier, S. Kohler, S. Halling, S. Leonard, C. Nijskens, J. Ferooz, P. Lestrate, R. M. Delrue, I. Danese, J. Vandenhaute, A. Tibor, X. DeBolle, and J. J. Letesson. 2005. The sheathed flagellum of Brucella melitensis is involved in persistence in a murine model of infection. Cell. Microbiol. 7687-698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guillemin, K., N. R. Salama, L. S. Tompkins, and S. Falkow. 2002. Cag pathogenicity island-specific responses of gastric epithelial cells to Helicobacter pylori infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 9915136-15141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hong, P. C., R. M. Tsolis, and T. A. Ficht. 2000. Identification of genes required for chronic persistence of Brucella abortus in mice. Infect. Immun. 684102-4107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hort, G. M., J. Weisenburger, B. Borsdorf, C. Peters, M. Banai, H. Hahn, J. Jacob, and M. E. Mielke. 2003. Delayed type hypersensitivity-associated disruption of splenic periarteriolar lymphatic sheaths coincides with temporary loss of IFN-gamma production and impaired eradication of bacteria in Brucella abortus-infected mice. Microbes Infect. 595-106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hsieh, C. S., S. E. Macatonia, C. S. Tripp, S. F. Wolf, A. O'Garra, and K. M. Murphy. 1993. Development of TH1 CD4+ T cells through IL-12 produced by Listeria-induced macrophages. Science 260547-549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kahl-McDonagh, M. M., P. H. Elzer, S. D. Hagius, J. V. Walker, Q. L. Perry, C. M. Seabury, A. B. den Hartigh, R. M. Tsolis, L. G. Adams, D. S. Davis, and T. A. Ficht. 2006. Evaluation of novel Brucella melitensis unmarked deletion mutants for safety and efficacy in the goat model of brucellosis. Vaccine 245169-5177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kahl-McDonagh, M. M., and T. A. Ficht. 2006. Evaluation of protection afforded by Brucella abortus and Brucella melitensis unmarked deletion mutants exhibiting different rates of clearance in BALB/c mice. Infect. Immun. 744048-4057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lestrate, P., R. M. Delrue, I. Danese, C. Didembourg, B. Taminiau, P. Mertens, X. De Bolle, A. Tibor, C. M. Tang, and J. J. Letesson. 2000. Identification and characterization of in vivo attenuated mutants of Brucella melitensis. Mol. Microbiol. 38543-551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Livak, K. J., and T. D. Schmittgen. 2001. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(−delta delta C(T)) method. Methods 25402-408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Molofsky, A. B., B. G. Byrne, N. N. Whitfield, C. A. Madigan, E. T. Fuse, K. Tateda, and M. S. Swanson. 2006. Cytosolic recognition of flagellin by mouse macrophages restricts Legionella pneumophila infection. J. Exp. Med. 2031093-1104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Murphy, E. A., J. Sathiyaseelan, M. A. Parent, B. Zou, and C. L. Baldwin. 2001. Interferon-gamma is crucial for surviving a Brucella abortus infection in both resistant C57BL/6 and susceptible BALB/c mice. Immunology 103511-518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Overbergh, L., A. Giulietti, D. Valckx, R. Decallonne, R. Bouillon, and C. Mathieu. 2003. The use of real-time reverse transcriptase PCR for the quantification of cytokine gene expression. J. Biomol. Tech. 1433-43. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pasquali, P., R. Adone, L. C. Gasbarre, C. Pistoia, and F. Ciuchini. 2001. Mouse cytokine profiles associated with Brucella abortus RB51 vaccination or B. abortus 2308 infection. Infect. Immun. 696541-6544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rafiei, A., S. K. Ardestani, A. Kariminia, A. Keyhani, M. Mohraz, and A. Amirkhani. 2006. Dominant Th1 cytokine production in early onset of human brucellosis followed by switching towards Th2 along prolongation of disease. J. Infect. 53315-324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ren, T., D. S. Zamboni, C. R. Roy, W. F. Dietrich, and R. E. Vance. 2006. Flagellin-deficient Legionella mutants evade caspase-1- and Naip5-mediated macrophage immunity. PLoS Pathog. 2e18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rieder, G., W. Fischer, and R. Haas. 2005. Interaction of Helicobacter pylori with host cells: function of secreted and translocated molecules. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 867-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rolan, H. G., and R. M. Tsolis. 2007. Mice lacking components of adaptive immunity show increased Brucella abortus virB mutant colonization. Infect. Immun. 752965-2973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Roux, C. M., H. G. Rolan, R. L. Santos, P. D. Beremand, T. L. Thomas, L. G. Adams, and R. M. Tsolis. 2007. Brucella requires a functional type IV secretion system to elicit innate immune responses in mice. Cell. Microbiol. 91851-1869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sathiyaseelan, J., R. Goenka, M. Parent, R. M. Benson, E. A. Murphy, D. M. Fernandes, A. S. Foulkes, and C. L. Baldwin. 2006. Treatment of Brucella-susceptible mice with IL-12 increases primary and secondary immunity. Cell. Immunol. 2431-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schmid, M. C., F. Scheidegger, M. Dehio, N. Balmelle-Devaux, R. Schulein, P. Guye, C. S. Chemmakesava, B. Biedermann, and C. Dehio. 2004. The VirB type IV secretion system of Bartonella henselae mediates invasion, proinflammatory activation and antiapoptotic protection of endothelial cells. Mol. Microbiol. 52141-147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sieira, R., D. J. Comerci, D. O. Sanchez, and R. A. Ugalde. 2000. A homologue of an operon required for DNA transfer in Agrobacterium is required in Brucella abortus for virulence and intracellular multiplication. J. Bacteriol. 1824849-4855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sporri, R., N. Joller, U. Albers, H. Hilbi, and A. Oxenius. 2006. MyD88-dependent IFN-gamma production by NK cells is key for control of Legionella pneumophila infection. J. Immunol. 1766162-6171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stinebring, W. R., and J. S. Youngner. 1964. Patterns of interferon appearance in mice infected with bacteria or bacterial endotoxin. Nature 204712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sun, Y. H., A. B. den Hartigh, R. L. Santos, L. G. Adams, and R. M. Tsolis. 2002. virB-mediated survival of Brucella abortus in mice and macrophages is independent of a functional inducible nitric oxide synthase or NADPH oxidase in macrophages. Infect. Immun. 704826-4832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sun, Y. H., H. G. Rolan, A. B. den Hartigh, D. Sondervan, and R. M. Tsolis. 2005. Brucella abortus virB12 is expressed during infection but is not an essential component of the type IV secretion system. Infect. Immun. 736048-6054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Swain, S. L., A. D. Weinberg, M. English, and G. Huston. 1990. IL-4 directs the development of Th2-like helper effectors. J. Immunol. 1453796-3806. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vendrell, J. P., A. Delobbe, M. F. Huguet, F. Peraldi, A. Serre, and A. Cannat. 1987. Biological properties of a panel of murine monoclonal anti-Brucella antibodies. Immunology 617-10. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Viala, J., C. Chaput, I. G. Boneca, A. Cardona, S. E. Girardin, A. P. Moran, R. Athman, S. Memet, M. R. Huerre, A. J. Coyle, P. S. DiStefano, P. J. Sansonetti, A. Labigne, J. Bertin, D. J. Philpott, and R. L. Ferrero. 2004. Nod1 responds to peptidoglycan delivered by the Helicobacter pylori cag pathogenicity island. Nat. Immunol. 51166-1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Young, E. 2000. Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett's principles and practice of infectious disease, vol. 2. Churchill Livingstone, Philadelphia, PA.

- 44.Zhan, Y., and C. Cheers. 1993. Endogenous gamma interferon mediates resistance to Brucella abortus infection. Infect. Immun. 614899-4901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]