Abstract

Spores of Clostridium perfringens possess high heat resistance, and when these spores germinate and return to active growth, they can cause gastrointestinal disease. Work with Bacillus subtilis has shown that the spore's dipicolinic acid (DPA) level can markedly influence both spore germination and resistance and that the proteins encoded by the spoVA operon are essential for DPA uptake by the developing spore during sporulation. We now find that proteins encoded by the spoVA operon are also essential for the uptake of Ca2+ and DPA into the developing spore during C. perfringens sporulation. Spores of a spoVA mutant had little, if any, Ca2+ and DPA, and their core water content was approximately twofold higher than that of wild-type spores. These DPA-less spores did not germinate spontaneously, as DPA-less B. subtilis spores do. Indeed, wild-type and spoVA C. perfringens spores germinated similarly with a mixture of l-asparagine and KCl (AK), KCl alone, or a 1:1 chelate of Ca2+ and DPA (Ca-DPA). However, the viability of C. perfringens spoVA spores was 20-fold lower than the viability of wild-type spores. Decoated wild-type and spoVA spores exhibited little, if any, germination with AK, KCl, or exogenous Ca-DPA, and their colony-forming efficiency was 103- to 104-fold lower than that of intact spores. However, lysozyme treatment rescued these decoated spores. Although the levels of DNA-protective α/β-type, small, acid-soluble spore proteins in spoVA spores were similar to those in wild-type spores, spoVA spores exhibited markedly lower resistance to moist heat, formaldehyde, HCl, hydrogen peroxide, nitrous acid, and UV radiation than wild-type spores did. In sum, these results suggest the following. (i) SpoVA proteins are essential for Ca-DPA uptake by developing spores during C. perfringens sporulation. (ii) SpoVA proteins and Ca-DPA release are not required for C. perfringens spore germination. (iii) A low spore core water content is essential for full resistance of C. perfringens spores to moist heat, UV radiation, and chemicals.

Clostridium perfringens food poisoning is caused mainly by enterotoxigenic type A isolates that have the ability to form metabolically dormant spores that are extremely resistant to heat, radiation, and toxic chemicals (45, 49, 50, 55). These highly resistant spores can survive traditional methods for cooking meat and poultry products as well as other processing treatments used in the food industry. The surviving spores can then go through germination and outgrowth, generating the vegetative cells that cause disease (30).

Spores of Bacillus species also have the extreme resistance of C. perfringens spores. The factors involved in Bacillus subtilis spore resistance include the following: (i) relatively impermeable spore inner membrane; (ii) low water content of the spore core; (iii) high levels of pyridine-2,6-dicarboxylic acid (dipicolinic acid [DPA]) in the spore core and the type and amount of cations chelated by DPA; and (iv) the saturation of spore DNA with α/β-type small, acid-soluble spore proteins (SASP) (63, 64). Studies have shown that α/β-type SASP are also an important factor in C. perfringens spore resistance to moist heat, UV radiation, and some chemicals (45, 49, 50), while small changes in the water content of the cores of these spores alter resistance to moist heat and nitrous acid (46).

Spore germination has been well studied in B. subtilis (34, 62) and can be initiated by a variety of compounds (termed germinants) including amino acids and some other nutrients and nutrient mixtures, a 1:1 chelate of Ca2+ and DPA (Ca-DPA), cationic surfactants, and hydrostatic pressure (41, 44). The germinant receptors, located in the spore's inner membrane (18, 43), sense nutrients present in the environment and stimulate the release of monovalent cations (H+, Na+, and K+), divalent cations (Ca2+, Mg2+, and Mn2+), and the spore core's large depot (∼25% of core weight [dry weight]) of DPA (62) present in a 1:1 chelate with divalent cations, predominantly Ca2+ (Ca-DPA) (35, 36, 59, 61). Ca-DPA release is crucial to spore progression from germination into outgrowth because of the following. (i) Water replaces Ca-DPA, thus elevating the spore core water content. (ii) Ca-DPA triggers the initiation of hydrolysis of the spore's peptidoglycan (PG) cortex by the cortex-lytic enzyme (CLE) CwlJ that is probably directly activated by Ca-DPA (42). Cortex hydrolysis then allows the core to expand and take up even more water to the level found in vegetative cells. This latter event restores protein movement and enzyme activity in the spore core and allows resumption of energy metabolism and macromolecular synthesis (9, 62).

Release of Ca-DPA during B. subtilis spore germination and DPA uptake during sporulation into the developing spore from the mother cell, the site of DPA synthesis, require the SpoVA proteins that may be components of some type of gated channel in the spore's inner membrane (70, 72). In B. subtilis, the hexacistronic spoVA operon encodes the SpoVA proteins (24), and most, if not all, of these are likely to be membrane proteins as shown directly for SpoVAD proteins (71). The spoVA operon is transcribed exclusively during B. subtilis sporulation in the developing forespore just prior to DPA uptake (68, 70). B. subtilis strains with deletions in the spoVA operon initiate sporulation, but the spoVA spores are extremely unstable and lyse during sporulation, probably because of their lack of DPA (68). B. subtilis spores that lack DPA due to inactivation of the DPA synthase are also unstable and lyse during sporulation (68). The reason for the instability of DPA-less B. subtilis spores is not clear but may be because the second of two redundant CLEs, SleB, is spontaneously activated in spores that lack DPA (68).

Clostridium species also contain a spoVA operon, although this operon is only tricistronic, containing spoVAC, spoVAD, and spoVAE (4, 5, 38, 56), suggesting that not all the SpoVA proteins in the spores of Bacillus species are essential for DPA movement during sporulation and spore germination in Clostridium species. To study the roles of SpoVA proteins and DPA levels in the properties of spores of Clostridium species, C. perfringens was used to examine the expression of the spoVA operon during growth and sporulation and to construct a spoVA deletion mutation. The properties of the resultant spoVA spores, in particular their Ca-DPA level, resistance, and germination, were then examined to help elucidate the roles of SpoVA proteins and DPA in C. perfringens spore properties. Surprisingly, while C. perfringens spoVA spores lacked DPA, these spores were stable and germinated relatively normally. However, these spoVA spores had significantly higher core water content and exhibited markedly decreased resistance to moist heat, UV radiation, and a number of chemicals than wild-type spores did.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and plasmids.

The C. perfringens strains and plasmids used in this study are described in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristic(s) | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| C. perfringens strains | ||

| SM101 | Electroporatable derivative of food poisoning type A isolate, NCTC8798; carries a chromosomal cpe | 74 |

| DPS104 | spoVA mutant (spoVA::tetM) derivative of SM101 | This study |

| SM101(pDP51) | Wild-type strain carrying spoVA-gusA fusion | This study |

| SM102(pDP79) | Wild-type strain carrying spoVAD-gusA fusion | This study |

| SM101(pDP80) | Wild-type strain carrying spoVAE-gusA fusion | This study |

| DP104(pDP54) | spoVA mutant complemented with wild-type spoVA | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pJIR418 | C. perfringens/E. coli shuttle vector; Cmr and Emr | 66 |

| pMRS127 | C. perfringens/E. coli shuttle vector carrying a promoterless gusA; Emr | 49 |

| pJIR599 | pBluescript II carrying erythromycin resistance gene (ermB); Emr | 2 |

| pJIR750 | C. perfringens/E. coli shuttle vector; Cmr | 3 |

| pJIR1886 | pBluescript II carrying tetracycline resistance gene (tetM); Tetr | J. I. Rood |

| pDP1 | gerAA internal fragment (∼800 bp) cloned in EcoRI site of pCR-XL-TOPO | D. Paredes-Sabja |

| pDP31 | ∼1.0-kb PCR fragment containing 730 bp upstream and 270 bp of the N-terminus-coding region of spoVAC in pCR-XL-TOPO | This study |

| pDP32 | ∼1.4-kb PCR fragment containing 324 bp of the C-terminus-coding region and 1,054-bp downstream of spoVAE in pCR-XL-TOPO | This study |

| pDP33 | ∼1.0-kb KpnI-SpeI fragment from pDP31 cloned between KpnI/SpeI sites of pDP1 | This study |

| pDP34 | ∼1.4-kb PstI-XhoI fragment from pDP32 cloned between PstI/XhoI sites of pDP33 | This study |

| pDP35 | ∼3.2-kb EcoRI fragment carrying tetM from pJIR1886 cloned in the EcoRI site of pDP34 | This study |

| pDP45 | ∼1.1-kb SmaI fragment carrying ermB from pJIR599 cloned in the SmaI site of pDP35 | This study |

| pDP51 | ∼ 393-bp PCR amplified upstream region of spoVAC cloned in pMRS127 | This study |

| pDP53 | ∼2.5-kb PCR fragment containing spoVA operon and upstream region cloned in pCR-XL-TOPO | This study |

| pDP54 | ∼2.5-kb KpnI-SalI fragment containing the spoVA operon and upstream region from pDP53 in pJIR750 | This study |

| pDP79 | ∼378 bp of PCR-amplified upstream region of spoVAD cloned in pMRS127 | This study |

| pDP80 | ∼351 bp of PCR-amplified upstream region of spoVAE cloned in pMRS127 | This study |

Construction of gusA fusion plasmids and GUS assay.

Expression of C. perfringens spoVAC, spoVAD, and spoVAE was examined by fusing DNA upstream of each gene to Escherichia coli gusA in pMRS127, an E. coli-C. perfringens shuttle vector (49). Briefly, 300- to 400-bp DNA fragments upstream of spoVAC, spoVAD, or spoVAE from C. perfringens SM101 were PCR amplified using primers CPP274/CPP275, CPP382/CPP381, and CPP387/CPP384 (the forward and reverse primers had SalI and PstI cleavage sites, respectively) (Table 2). These PCR fragments were digested with SalI and PstI and cloned between the SalI and PstI cleavage sites in pMRS127 to create spoVAC-gusA, spoVAD-gusA, and spoVAE-gusA fusion constructs, giving plasmids pDP51, pDP79, and pDP80, respectively (Table 1). These plasmids were introduced into C. perfringens SM101 by electroporation (10), and erythromycin-resistant (Emr) (50 μg/ml) transformants were selected. The transformants carrying the plasmid with the spoVAC-gusA, spoVAD-gusA, or spoVAE-gusA fusion were grown vegetatively in TGY medium (3% Trypticase soy, 2% glucose, 1% yeast extract, 0.1% l-cysteine) (22), sporulated in Duncan-Strong (DS) (11) medium, and assayed for β-glucuronidase (GUS) activity as described previously (17, 49). GUS specific activity was expressed in Miller units and calculated as described previously (21).

TABLE 2.

Primers used in this study

| Primer name | Primer sequencea | Positionsb | Genes | Usec |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CPP288 | GGGTACCCCTATGAGGATATATTTCAGATTGGG | −731 to −706 | spoVAC | MP |

| CPP289 | GACTAGTCTGCTCCAGCCTTAGCGGC | +252 to +270 | spoVAC | MP |

| CPP290 | GCTGCAGCGGTGCAATCTGTGTAATAGGACAG | +42 to +66 | spoVAE | MP |

| CPP291 | CCTCGAGGCTTGTGCAGACAGTCCTAAGC | +1399 to +1420 | spoVAE | MP |

| CPP341 | GGGTACCCGATGAAGGAACGCCGGTT | −393 to −375 | spoVAC | CP |

| CPP347 | GCGTCGACGTACAACTAAAAAAGCTGTACCT | +521 to +544 | spoVAE | CP |

| CPP274 | GCGTCGACGATGAAGGAACGCCGGTT | −393 to −375 | spoVAC | GUS |

| CPP275 | GCTGCAGAGCTATATTAATCACCCTTTTCTATT | −27 to −1 | spoVAC | GUS |

| CPP382 | GCAGCGTCGACGTAGGTGGATTAATTTGTGTAATAGG | −371 to −346 | spoVAD | GUS |

| CPP381 | GACGCTGCAGTACTCATTCTTATCACCCCAC | −14 to + 7 | spoVAD | GUS |

| CPP387 | GCAGCGTCGACAAAGAGTATGGATATGATATTAGTAAGG | −335 to −307 | spoVAE | GUS |

| CPP384 | GACGCTGCAGCTTGCAAAATTCTCATCTCCTCATTATT | −12 to +16 | spoVAE | GUS |

Restriction sites are marked by underlining.

The nucleotide position numbering begins from the first codon and refers to the relevant position within the respective gene sequence.

MP, construction of mutator plasmid; CP, construction of complemented plasmid; GUS, construction of gusA fusion plasmid.

Construction of a C. perfringens spoVA deletion mutant.

To isolate a derivative of C. perfringens SM101 with a deletion of the entire spoVA operon, a ΔspoVA suicide vector was constructed as follows. A 1,001-bp DNA fragment carrying 270 bp from the N-terminal coding region and 731 bp upstream of spoVAC was PCR amplified using primers CPP288/CPP289 (Table 2), which had KpnI and SpeI cleavage sites at the 5′ ends of the forward and reverse primers, respectively. A 1,378-bp fragment carrying 324 bp from the C-terminal coding region and 1,054 bp downstream of spoVAE was PCR amplified using primers CPP290/CPP291 (Table 2), which had PstI and XhoI cleavage sites at the 5′ ends of the forward and reverse primers, respectively (Table 2). These PCR fragments were cloned into plasmid pCR-XL-TOPO, giving plasmids pDP31 and pDP32. An ∼1.0-kb KpnI-SpeI fragment from pDP31 was cloned into pDP1 (Table 1), giving plasmid pDP33, and an ∼1.4-kb PstI-XhoI fragment from pDP32 was cloned in pDP33, giving pDP34. Next, an ∼3.2-kb EcoRI fragment carrying the tetracycline resistance gene (tetM) from pJIR1886 (Table 1) was cloned into the EcoRI site of pDP34, giving pDP35. Finally, an ∼1.1-kb SmaI fragment carrying the erythromycin resistance gene (ermB) from pJIR599 (Table 1) was cloned into a unique SmaI site in pDP35, giving pDP45 which cannot replicate in C. perfringens. Plasmid pDP45 was introduced into C. perfringens SM101 by electroporation (10), and the C. perfringens spoVA deletion strain DPS104 was isolated by allelic exchange (54). The presence of the spoVA deletion in strain DPS104 (Fig. 1A) was confirmed by PCR and Southern blot analyses (data not shown).

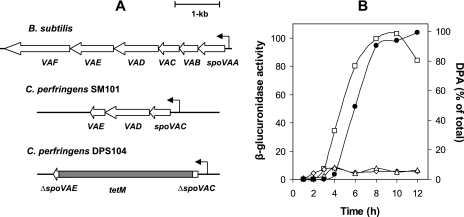

FIG. 1.

Arrangement of the spoVA operon in B. subtilis and in C. perfringens strains and expression of the spoVA operon during C. perfringens sporulation. (A) The arrangement of the spoVA operons of the various organisms is shown with the location of the known (B. subtilis) and putative (C. perfringens) promoters indicated by the leftward pointing arrows. (B) The GUS specific activity from the spoVAC-gusA fusion (open squares), spoVAD-gusA fusion (open diamonds), or spoVAE-gusA fusion (open triangles) and the level of DPA accumulated (filled circles) in C. perfringens SM101 grown in sporulation medium were determined as described in Materials and Methods.

Construction of a spoVA-complemented strain.

An ∼2.5-kb fragment containing spoVAC, spoVAD, and spoVAE plus 393 bp upstream of spoVAC was PCR amplified using primers CPP341/CPP347 (Table 2) and cloned into pCR-XL-TOPO (Invitrogen), giving pDP53. The ∼2.5-kb KpnI-SalI fragment of pDP53 was cloned between the KpnI and SalI sites of plasmid pJIR750 (3) to create the spoVA-complementing plasmid, pDP54. Plasmid pDP54 was introduced into C. perfringens strain DPS104 by electroporation (10), and chloramphenicol-resistant (Cmr) transformants were selected. The presence of plasmid pDP54 in C. perfringens DPS104(pDP54) was confirmed by PCR (data not shown).

Spore preparation and purification.

Starter cultures (10 ml) of C. perfringens isolates were prepared by overnight growth at 37°C in fluid thioglycolate broth (FTG) (Difco) as described previously (22). Sporulating cultures of C. perfringens were prepared by inoculating 0.2 ml of an FTG starter culture into 10 ml of DS sporulation medium (11), and this culture was incubated for 24 h at 37°C to form spores as confirmed by phase-contrast microscopy. Large amounts of spores were prepared by scaling up the latter procedure. Spore preparations were cleaned by repeated centrifugation and washing with sterile distilled water until the spores were >99% free of sporulating cells, cell debris, and germinated spores, suspended in distilled water to a final optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of ∼6, and stored at −20°C (47).

Measurement of spore properties.

For most analyses of spore Ca2+ and DPA content, spore coats were extracted to remove material that might interfere with the quantitation of either the amount of spores being assayed or the amount of DPA. Spore coats were extracted from a spore suspension with an OD600 of ∼20 in 1 ml of 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0)-8 M urea-1% (wt/vol) sodium dodecyl sulfate-50 mM dithiothreitol for 90 min at 37°C (treatment 1), and the spores were washed three times with 150 mM NaCl and twice with water (48). Note that this extraction procedure did not kill spores as determined on plates containing lysozyme (see Results). An aliquot of decoated spores at an OD600 of 12 was incubated at 100°C for 60 min, the sample was cooled on ice and centrifuged for 5 min, and Ca2+ and DPA were measured in the supernatant fluid as described previously (51, 73). While most analyses used decoated spores, similar results were obtained when spores were not initially decoated.

For determination of spore core densities (wet weight) by equilibrium density gradient centrifugation (27), decoated spores were suspended in 100 μl of 30% Histodenz (Nycodenz) (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), incubated for 60 min on ice, loaded on the top of 2-ml step gradients of 51 to 70% (for spoVA spores) or 61 to 80% (for wild-type spores) Histodenz in ultraclear centrifuge tubes, and the tubes were centrifuged for 45 min at 14,000 rpm and 20°C in a swinging bucket rotor in a Beckman TL-100 ultracentrifuge (27).

Spore germination assays.

Spore suspensions were heat activated at 80°C for 10 min, cooled in water at ambient temperature for 5 min, and subsequently incubated at 40°C for 10 min as described previously (47). Spore germination with nutrients or Ca-DPA (50 mM CaCl2 and 50 mM DPA adjusted to pH 8.0 with Tris base) was routinely measured by monitoring the OD600 of spore cultures (Smartspec 3000 spectrophotometer; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA), which falls ∼60% upon complete germination of wild-type spores, and the levels of germination were confirmed by phase-contrast microscopy. However, upon complete germination of spoVA spores, the OD600 fell by only ∼40% due to the lower refractive index of spoVA spores. The extent of spore germination was calculated by measuring the decrease in OD600 and expressed as a percentage of the initial OD600. All values reported are averages of two experiments performed on at least two independent spore preparations, and individual values varied by less than 10% from the average values shown.

Decoating treatments.

Spores (1 ml at an OD600 of 20) were decoated either by treatment 1 as described above or in 1 ml of 0.1 M sodium borate (pH 10)-2% 2-mercaptoethanol for 60 min at 37°C (32) (treatment 2). Decoated spores were washed at least nine times with sterile distilled water before use.

DPA release.

DPA release from untreated or decoated spores during nutrient germination was measured by heat activating a spore suspension (OD600 of 1.5) as described above, cooling, and incubating with 100 mM AK (100 mM l-asparagine and 100 mM KCl) in 25 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) at 40°C for 60 min. For measuring DPA release during dodecylamine germination, untreated or decoated spores (OD600 of 1.5) were incubated at 60°C with 1 mM dodecylamine in 25 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4). Aliquots (1 ml) of germinating cultures were centrifuged for 2 min at 8,000 rpm in a microcentrifuge, and DPA in the supernatant fluid was measured by monitoring the OD270 as described previously (6, 47). The total DPA content of wild-type spores was measured by boiling an aliquot (1 ml) for 60 min, centrifuging at 8,000 rpm in a microcentrifuge for 15 min, and measuring the OD270 of the supernatant fluid as described previously (6, 47). In B. subtilis spores, ≥85% of the material absorbing at 270 nm is DPA (1, 6).

Assessment of colony-forming efficiency of spores.

To assess the colony-forming efficiency of untreated and decoated spores, spores at an OD600 of 1 were heat activated at 80°C for 10 min, aliquots of various dilutions were plated on brain heart infusion (BHI) agar with or without lysozyme (1 μg/ml) in the plates, the plates were incubated at 37°C anaerobically for 24 h, and colonies were counted.

SASP extraction.

Extraction of SASP from C. perfringens spores and their analysis by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis at low pH were as described previously (49, 50). Briefly, SASP were extracted from 40 mg (dry weight) of disrupted spores with dilute acid, and the extracts were processed and lyophilized. The dry residue was dissolved in 30 μl of 8 M urea, 5-μl aliquots were run on polyacrylamide gels at low pH, and the gels were stained with Coomassie brilliant blue (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA), all as described previously (50). Analysis of relative band intensities on stained gels by densitometry was performed using the public domain NIH Image program (developed at the U.S. National Institutes of Health and available on the Internet at http://rsb.info.nih.gov/nih-image/).

Spore resistance.

The resistance of C. perfringens spores to moist heat was measured as described previously (49, 55). Briefly, cultures of C. perfringens strains that had been grown on DS medium for 24 h were heat treated at 75°C for 20 min to kill vegetative cells. The number of initial CFU was determined by serially diluting heat-treated spore cultures grown in DS medium in phosphate-buffered saline (140 mM NaCl-25 mM sodium phosphate buffer [pH 7.0]), plating on BHI agar, and anaerobic incubation for 24 h at 37°C. The spore cultures grown in DS medium and treated at 75°C were then heated at 94 or 100°C for various times, aliquots of appropriate dilutions were plated, and the plates were incubated anaerobically for 24 h at 37°C as described above. Plots of CFU/ml versus time at 94 or 100°C were used to determine decimal reduction values (D94°C or D100°C values), which are the times cultures need to be kept at 94 or 100°C to achieve 90% reduction in CFU/ml.

C. perfringens spore resistance to UV radiation was determined as described previously (48, 50). Briefly, purified spores at an OD600 of 2 were diluted 100-fold in 25 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 6.8) and UV irradiated at 254 nm with a UVGL-25 Mineralight lamp (UVP Inc., Upland, CA) for various times. Appropriate dilutions were spread onto BHI plates and incubated as described above prior to assessment of colony formation.

The resistance of C. perfringens spores to chemicals was determined as described previously (45). Briefly, purified spores at an OD600 of ∼1 were treated as follows. (i) The spores were treated with 2 M hydrogen peroxide (Mallinckrodt Baker Inc., Phillipsburg, NJ) at room temperature, and aliquots were neutralized with catalase (Sigma) as described previously (57). (ii) The spores were treated with 300 mM HCl at room temperature, and aliquots were diluted 100-fold in 25 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0). (iii) The spores were treated with 400 mM NaNO2-400 mM Na acetate buffer (pH 4.5) at room temperature, and aliquots were diluted 10-fold in 500 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 8.5). (iv) The spores were treated with 25 g/liter formaldehyde (Sigma) at 30°C, and aliquots were diluted 10-fold in 400 mM glycine (pH 7.0) and incubated for 20 min at room temperature prior to analysis. Determination of spore killing was as described above.

RESULTS

Identification of the putative spoVA operon in C. perfringens.

The SpoVA proteins are encoded by six open reading frames (ORFs) in a hexacistronic operon in B. subtilis (24). In contrast, only three ORFs (CPR2017, CPR2018, and CPR2019) encoding proteins with high similarity (65 to 73%) to B. subtilis SpoVA proteins were found in the C. perfringens SM101 genome (37) (Fig. 1A). These ORFs are annotated as spoVAC (CPR2019), spoVAD (CPR2018), and spoVAE (CPR2017) and form a putative tricistronic operon. This organization of the spoVA operon is not unique to C. perfringens, as it is conserved among Clostridium species (4, 5, 38, 56). The first gene in the putative tricistronic operon, spoVAC (CPR2019), is predicted to encode a 155-residue protein with four transmembrane alpha-helical segments (TMS). The spoVAD gene (CPR2018) is predicted to encode a protein of 339 amino acid residues with no TMS; perhaps this is a peripheral inner membrane protein that interacts with other inner membrane proteins. The spoVAE gene (CPR2017) is predicted to encode a 121-residue protein with four TMS.

Expression of C. perfringens spoVA genes.

To assess whether the putative C. perfringens spoVA genes are expressed uniquely during sporulation and comprise a tricistronic operon, DNA upstream of each gene was fused to E. coli gusA, and GUS activity was measured after introduction of the various fusions into C. perfringens SM101. No significant GUS activity was observed in vegetative cultures carrying plasmid pDP51 with a spoVAC-gusA fusion (data not shown). However, a sporulating culture carrying plasmid pDP51 (spoVAC-gusA) exhibited significant GUS activity (Fig. 1B), indicating that a sporulation-specific promoter is located upstream of spoVAC. Expression of GUS from the spoVAC-gusA fusion began ∼3 h after induction of sporulation, and GUS specific activity reached a maximum 8 to 10 h after initiation of sporulation and then fell somewhat (Fig. 1B). The decrease in GUS specific activity late in sporulation is consistent with spoVA being packaged into the spore where it cannot be easily assayed (29). Phase bright spores became visible ∼6 h after induction of sporulation (data not shown), when ∼50% of the spore's maximum DPA level had been accumulated, and DPA accumulation lagged ∼1 h behind expression of the spoVA operon (Fig. 1B). Thus, spoVAC and probably spoVA operon transcription and accumulation of the SpoVA proteins precede DPA accumulation by the developing spore, as is also the case in B. subtilis (29).

In contrast to the results with the spoVAC-gusA fusion, there was no detectable GUS activity observed in either vegetative or sporulating cultures carrying plasmids pDP79 (spoVAD-gusA) or pDP80 (spoVAE-gusA) (Fig. 1B and data not shown). These results indicate that no promoter is present in DNA 300 to 400 bp upstream of spoVAD or spoVAE, and thus, these genes almost certainly form a tricistronic operon in C. perfringens with spoVAC as the first gene in the operon, and these results further indicate that this operon is expressed only during sporulation.

Effect of a spoVA mutation on C. perfringens spore properties.

Previous studies with B. subtilis (12-14, 33, 68) have shown that sporulation of strains with null mutations in any of the first five cistrons of the spoVA operon gives immature forespores that lyse within the sporangium. Isolation of stable spoVA spores in B. subtilis requires the elimination of either all three functional nutrient germinant receptors or the CLE, SleB (68). Surprisingly, spores of the C. perfringens spoVA mutant (strain DPS104) were stable, appeared bright when viewed by phase-contrast microscopy, and were easily purified to give clean spore preparations containing >95% free spores. As expected, the Ca2+ and DPA contents of C. perfringens spoVA spores were negligible compared to those in wild-type spores (Table 3). Sporulation of C. perfringens strain DPS104 with DPA present in the sporulation medium at 100 μg/ml also gave spores that contained no DPA (data not shown), although this exogenous DPA level restores nearly wild-type DPA levels to spores of B. subtilis strains defective in DPA synthase (12, 13, 33, 40). However, attempts to correct the DPA-less phenotype of spoVA spores by complementation with the wild-type spoVA operon failed, as the DPA level in C. perfringens DPS104(pDP54) spores was similar to that of spoVA spores (data not shown). Together the latter findings indicate that SpoVA proteins are essential for Ca-DPA uptake during C. perfringens sporulation. Interestingly, the molar ratio of Ca2+ to DPA in C. perfringens wild-type spores was 0.7:1, indicating that DPA may also be forming complexes with other divalent cations, such as Mg2+ and Mn2+ (Table 3) (16, 35, 36, 59, 61).

TABLE 3.

Effects of spoVA mutation on C. perfringens spore properties

| Strain (genotype) | DPA (μg/ml/OD600)a | Ca2+ (μg/ml/OD600)a | Core density (g [wet weight]/ml)b | Water content (g/100 g of protoplast [wet weight])c |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SM101 (wild type) | 21.7 | 3.6 | 1.381 | 31 |

| DPS104 (spoVA) | <0.27 | <0.07 | 1.303 | 62 |

Values are averages of determinations on three different spore preparations.

Values are averages of determination of two different spore preparations that differed by ≤0.003 g/ml.

Spore core water content was calculated according to the formula y = −0.00254x + 1.460 (27), where y is the spore core density (wet weight) and x is the core water content in grams per 100 g of protoplast (core) weight (wet weight).

As noted above, the C. perfringens spoVA spores appeared bright when observed by phase-contrast microscopy, suggesting that the cores of these spores were less hydrated than the protoplast of growing cells. However, the spoVA spores were less bright than wild-type spores (data not shown), suggesting that the cores of these spores are not as dehydrated as those of wild-type spores. Indeed, the core density (wet weight) of spoVA spores was significantly lower than that of wild-type spores (Table 3). The latter difference indicated that the spoVA spore core contains almost twice as much water per gram (wet weight) as the wild-type spore core does (Table 3).

In addition to differences in Ca-DPA content and core density (wet weight) between wild-type and spoVA spores, spoVA spores had lower colony-forming efficiency than wild-type spores did. When wild-type and spoVA spores were heat activated (80°C, 10 min), plated on BHI agar, and incubated overnight at 37°C under anaerobic conditions, the viability of spoVA spores was ∼20-fold lower than that of wild-type spores (Table 4). The lower apparent viability of spoVA spores was not due to their killing during heat activation, as unheated spoVA spores actually gave sixfold-fewer colonies than heat-activated spoVA spores (data not shown). The viability of the spoVA spores was also not increased on plates containing lysozyme (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Colony formation by spores of C. perfringens strainsa

| Treatmentb and strain (genotype) | Spore titer (CFU/ml/OD600)c

|

|

|---|---|---|

| BHI | BHI + Lyzd | |

| No treatment | ||

| SM101 (wild type) | 3.7 × 107 | 4.6 × 107 |

| DPS104 (spoVA) | 1.9 × 106 | 2.2 × 106 |

| Treatment 1 | ||

| SM101 (wild type) | 3.3 × 103 | 9.8 × 107 |

| DPS104 (spoVA) | 2.2 × 103 | 1.7 × 106 |

| Treatment 2 | ||

| SM101 (wild type) | 3.6 × 106 | 3.7 × 107 |

| DPS104 (spoVA) | 9.3 × 105 | 5.7 × 106 |

Heat-activated spores of various strains were plated on BHI agar, and colonies were counted after anaerobic incubation at 37°C for 24 h.

Spores were decoated by treatment 1 or treatment 2.

The titers are the averages from three experiments.

BHI plates containing 1 μg/ml lysozyme.

Effect of a spoVA mutation on germination of C. perfringens spores.

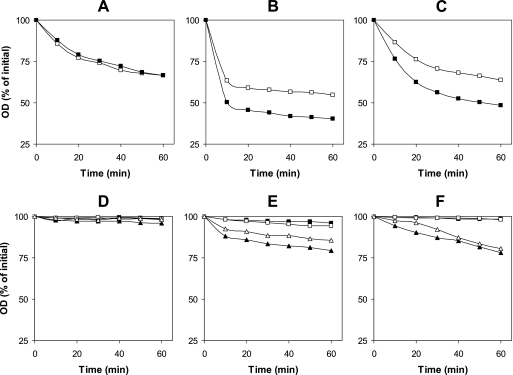

One possible explanation for the lower viability of the C. perfringens spoVA spores noted above is that Ca-DPA and/or SpoVA proteins are also essential for the germination of C. perfringens spores. If this is correct, then C. perfringens spoVA spores should germinate to a much lower extent than wild-type spores do. However, wild-type and spoVA spores germinated similarly in BHI broth through 60 min of incubation (Fig. 2A). Although the decreases in OD600 of wild-type and spoVA spores incubated aerobically at 40°C in BHI broth for 18 h to inhibit cell growth were 60 and 45%, respectively (data not shown), phase-contrast microscopy revealed that >99% of both the spoVA and wild-type spores had become phase dark and thus had germinated fully. Similarly, while spoVA spores appeared to germinate to a lesser extent than wild-type spores incubated with AK or Ca-DPA for 60 min when spore germination was monitored by the OD600 of the cultures (Fig. 2B and C), phase-contrast microscopy indicated again that >99 and ∼90% of both the wild-type and spoVA spores incubated with AK and Ca-DPA had germinated fully, respectively (data not shown). To more rigorously quantify this result, spoVA and wild-type spores were germinated with 100 mM AK (pH 7.0) at 40°C for 80 min. While >99% of the spores of both strains had become phase dark as determined by phase-contrast microscopy, the OD600 of the germinating wild-type and spoVA spore cultures had decreased by 62 and 42%, respectively (average of four independent experiments). These results indicate the following. (i) As suggested above, the refractive index of spoVA spores, and thus, their OD600 is ∼30% lower than that of wild-type spores, most likely due to the higher water content in the spoVA spore core; consequently, the difference between the OD600 of a culture of dormant and fully germinated spores is ∼30% greater for wild-type spores. (ii) DPA-less C. perfringens spores are able to germinate normally with either nutrients or exogenous Ca-DPA.

FIG. 2.

Germination of intact and decoated C. perfringens wild-type and spoVA spores with various germinants. (A to C) Heat-activated intact spores of strains SM101 (wild type) (filled squares) and DPS104 (spoVA) (open squares) were incubated at 40°C with BHI broth (A), 100 mM AK (B), or 50 mM Ca-DPA (C), and at various times, the OD600 was recorded as described in Materials and Methods. (D to F) Spores were decoated by treatment 1 (squares) or treatment 2 (triangles). Decoated spores of strains SM101 (wild type) (filled symbols) and DPS104 (spoVA) (open symbols) were heat activated and incubated with BHI broth (D), 100 mM AK (E), or 50 mM Ca-DPA (F), and at various times, the OD600 was recorded as described in Materials and Methods. No significant germination of intact or decoated spores of strain SM101 or DPS104 was observed when heat-activated spores were incubated in 25 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) at 40°C for 60 min.

Germination of decoated C. perfringens spores.

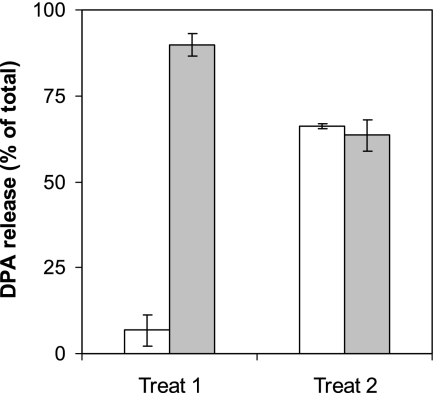

The results noted above suggested that cortex hydrolysis during C. perfringens spore germination can be independent of both SpoVA proteins and any signaling by Ca-DPA, and thus, perhaps CLEs are not activated directly by Ca-DPA in C. perfringens. To begin to examine the roles of CLEs in C. perfringens spore germination, we decoated wild-type and spoVA spores with treatments that are reported to remove CLEs (32, 42) and examined germination of the decoated spores. While it is still not clear which C. perfringens CLEs identified by analyses of enzyme activity on spore cortex peptidoglycan in vitro are actually involved in cortex PG degradation during spore germination, it was notable that both wild-type and spoVA spores decoated by treatment 1 were unable to germinate and remained phase bright when incubated for 60 min with BHI, AK, or Ca-DPA (Fig. 2D, E, and F and data not shown). Even after an 18-h incubation, >99% of these decoated spores remained phase bright (data not shown). These results are consistent with treatment 1 removing or inactivating all CLEs in C. perfringens spores, including any putative CLE directly activated by Ca-DPA. Although wild-type and spoVA spores decoated with treatment 2 exhibited little germination after incubation at 40°C for 60 min in BHI broth (Fig. 2D), ∼20% of the spores had become phase dark after 18 h of incubation (data not shown). In addition, wild-type and spoVA spores decoated by treatment 2 did germinate at a very low rate with AK or Ca-DPA (Fig. 2E and F), and ∼30% of the spores were phase dark after 18 h of incubation with AK and Ca-DPA (data not shown), consistent with treatment 2 completely removing the CLE SleC but removing only ∼90% of SleM from C. perfringens spores (23). Interestingly, no DPA was released from the cores of wild-type spores decoated with treatment 1 when these spores were incubated with AK, yet nearly all the spore's DPA was released when these spores were incubated with dodecylamine (Fig. 3), suggesting that perhaps the spore's germinant receptors had been damaged by treatment 1. In contrast, wild-type spores decoated with treatment 2 did release DPA when incubated with AK or dodecylamine (Fig. 3). These results strongly suggest that spoVA spores need undamaged germinant receptors and at least one CLE to initiate cortex hydrolysis during spore germination.

FIG. 3.

DPA release from decoated C. perfringens spores incubated with various germinants. Spores of C. perfringens strain SM101 (wild type) were decoated by either treatment 1 (Treat 1) or treatment 2 (Treat 2). Decoated spores were germinated with 100 mM AK and 25 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) for 60 min at 37°C (white bars) or with 1 mM dodecylamine and 25 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4) for 60 min at 60°C (gray bars), and DPA release was measured as described in Materials and Methods.

Colony-forming efficiency of decoated C. perfringens spores.

The extremely poor germination of the decoated spores noted above suggested that decoated wild-type and spoVA spores might have much lower colony-forming efficiency than intact spores do. Indeed, when heat-activated wild-type and spoVA spores were plated on BHI agar and incubated for 24 h at 37°C under anaerobic conditions, the colony-forming efficiencies of wild-type and spoVA spores decoated by treatment 1 were ∼104- and 103-fold lower, respectively, than those of the corresponding intact spores (Table 4). No additional colonies appeared when plates were incubated for up to 3 days. Wild-type and spoVA spores decoated with the milder treatment (treatment 2) exhibited much smaller decreases in colony-forming efficiencies (Table 4). Strikingly, when spores decoated with either treatment were plated on BHI agar containing 1 μg/ml lysozyme, the colony-forming efficiencies were restored to those of the corresponding intact spores (Table 4). These results indicate that the decoating treatments had not simply killed the spores.

Levels of α/β-type SASP in wild-type and spoVA spores.

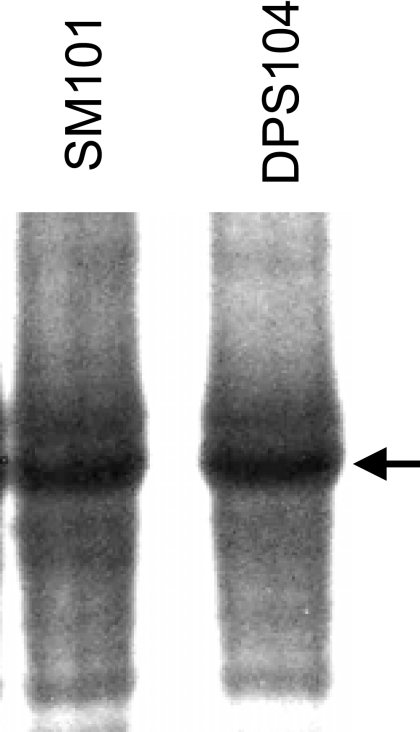

In B. subtilis, α/β-type SASP are degraded during the first minute of germination (52, 60) by a germination-specific protease (GPR) specific for a highly conserved sequence found in all SASP (64, 67). B. subtilis GPR is synthesized as a zymogen with a molecular mass of ∼46 kDa (termed P46) beginning at approximately the third hour of sporulation (53) and is autoprocessed to the ∼41-kDa active protease (P41) about 2 h later. This latter autoprocessing is triggered synergistically by Ca-DPA accumulation in the forespore and by decreases in the developing forespore's core pH and water content, conditions that preclude attack of P41 on its SASP substrates (19, 20, 53). C. perfringens also contains a gpr gene encoding a protein with high similarity to B. subtilis GPR, including the highly conserved P46 → P41 autoprocessing site (53). If P46 autoprocessing is regulated in C. perfringens as it is in B. subtilis, perhaps little, if any, GPR is autoprocessed to P41 during sporulation of C. perfringens strain DPS104 (spoVA). However, if P41 is present in C. perfringens spoVA spores, perhaps this protease can catalyze some SASP hydrolysis in the more hydrated core of spoVA spores. Given the important role played by α/β-type SASP in C. perfringens spore resistance (45, 49, 50), it was thus of interest to compare the levels of α/β-type SASP in C. perfringens spoVA and wild-type spores. Polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis at low pH of a SASP extract from wild-type and spoVA spores gave only a tight group of protein bands (Fig. 4), one of which was a major one, as seen previously (50). The intensities of these bands, and thus total α/β-type SASP levels, were similar in extracts from spores of these two strains (Fig. 4), as was confirmed by densitometric analysis of gels from three independent experiments (data not shown). These results suggest that either little, if any, P46 is autoprocessed to P41 during sporulation of strain DPS104 (spoVA) or the hydration level of the spoVA spore core is still low enough to preclude P41 activity on α/β-type SASP. It is also possible that the binding of α/β-type SASP to DNA in the spoVA spores helps protect these proteins against GPR digestion (19, 20, 53) (but see Discussion).

FIG. 4.

Levels of α/β-type SASP in C. perfringens wild-type and spoVA spores. Spores of C. perfringens strains SM101 (wild type) and DPS104 (spoVA) were dry ruptured, SASP were extracted, and extracts were processed and lyophilized The dry residue was dissolved in 30 μl of 8 M urea, 5-μl aliquots were run on polyacrylamide gels at low pH, and the gel was stained as described in Materials and Methods. The arrow indicates the major band reactive with antibody to the B. subtilis α/β-type SASP, SspC (50).

Moist heat, UV, and chemical resistance of C. perfringens spoVA spores.

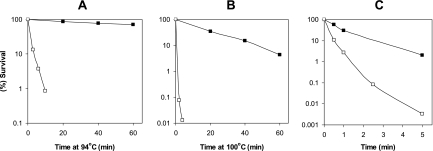

Previous work (49, 50) has shown that binding of α/β-type SASP to DNA is a major factor in C. perfringens spore resistance to moist heat and UV radiation and that small changes in spore core water content have significant effects on spore resistance to moist heat and nitrous acid but not UV radiation (46). As expected, C. perfringens spoVA spores were very sensitive to moist heat (Fig. 5A and B), with 70- to 80-fold lower D94°C (5 min; results from three independent experiments) and D100°C (0.5 min) values than wild-type spores (D94°C, 410 min; D100°C, 45 min). However, the heat resistance of spoVA spores could not be restored to wild-type levels by complementation with the wild-type spoVA operon, as the heat resistance of C. perfringens DPS104(pDP54) spores was similar to that of spoVA spores (data not shown). The spoVA spores were also significantly more sensitive to UV radiation than wild-type spores were (Fig. 5C).

FIG. 5.

Resistance of C. perfringens wild-type and spoVA spores to moist heat at 94°C (A) or 100°C (B) and to UV radiation (C). Spore cultures grown in DS medium or purified spores of C. perfringens strains SM101 (wild type) (filled squares) and DPS104 (spoVA) (open squares) were used to measure survival upon various treatments as described in Materials and Methods. The variability of the survival values in these experiments was ±20%.

Previous studies (46) have also shown that the resistance of C. perfringens mutant spores with slightly higher core water content to hydrogen peroxide and HCl is essentially identical to that of wild-type spores. However, C. perfringens spoVA spores with approximately twofold-higher water content than wild-type spores were more sensitive than wild-type spores not only to nitrous acid (Fig. 6A) but also to HCl (Fig. 6B), formaldehyde (Fig. 6C), and hydrogen peroxide (Fig. 6D).

FIG. 6.

Resistance of C. perfringens wild-type and spoVA spores to nitrous acid (A), HCl (B), formaldehyde (C), and hydrogen peroxide (D). Spores of C. perfringens strains SM101 (wild type) (filled squares) and DPS104 (spoVA) (open squares) were purified, and their survival upon various treatments was measured as described in Materials and Methods. The variability of the survival values in these experiments was ±15%.

DISCUSSION

The work in this communication indicates that C. perfringens spoVA spores accumulate no Ca-DPA and do not take up exogenous DPA and that the spoVA operon is expressed only during C. perfringens sporulation. These results are similar to those found with B. subtilis (13, 40, 68) and indicate that in C. perfringens the spoVA operon also encodes sporulation-specific genes essential for the uptake of Ca2+ and DPA during spore maturation. Unfortunately, we were unable to restore the DPA-less phenotype of C. perfringens spoVA spores by complementation with a wild-type spoVA operon, although the reason for this failure is not clear. Perhaps an alternative approach, such as introduction of the C. perfringens spoVA operon into a B. subtilis spoVA strain and vice versa could be successful. It was, however, most striking that sporulation of the C. perfringens spoVA strain gave stable Ca-DPA-less spores, since B. subtilis spoVA strains give only immature spores that lyse during sporulation, probably due to their germination within the sporangium (13, 68). Spores of B. subtilis strains that cannot synthesize DPA are also unstable and lyse during sporulation (13, 40). B. subtilis spores with significantly lower than normal DPA levels can be isolated, but they exhibit relatively rapid spontaneous germination (28). Thus, B. subtilis spores with low or no DPA levels, for whatever reason, spontaneously and rapidly trigger subsequent events in the spore germination process, most notably the hydrolysis of cortex PG. Indeed, the activity of one of the two redundant CLEs, CwlJ, appears to be directly stimulated by Ca-DPA, while the second redundant CLE, SleB, is somehow activated in spores that lack DPA or have low DPA, possibly responding to a change in the strain on cortex PG (42, 68). However, clearly, the CLEs in C. perfringens spores are not activated in spores that lack DPA. The reason for the stability of the DPA-less C. perfringens spoVA spores is unclear and may well reflect significant differences in the signaling mechanisms operating during germination of B. subtilis and C. perfringens spores, in particular the signaling mechanisms involving Ca-DPA. It will obviously be of great interest in future work to determine whether C. perfringens spores also have a CLE whose activity responds directly to DPA or Ca-DPA, although work thus far indicates that Ca-DPA triggers germination of these spores by acting through a nutrient germinant receptor (47).

In addition to the major general conclusions noted above, the current work also strongly indicates that the core water content plays a major role in the resistance of C. perfringens spores to moist heat. A recent study (46) found that wild-type C. perfringens spores from cultures grown at 42°C had ∼20% less core water than spores from cultures grown at 26°C and that D100°C values for moist heat were approximately fourfold lower in spores at 26°C than in spores at 42°C, both of which had essentially identical DPA levels. In the current work, an approximately twofold-higher core water content in spoVA spores was accompanied by an 80-fold-lower D100°C value. While some of the effects on the resistance of spoVA spores to moist heat may be due to the loss of specific protective effects of Ca-DPA, most previous work (15), primarily with spores of Bacillus species, has found a strong inverse relationship between a spore's moist heat resistance and its core water content; this also seems to be true for C. perfringens spores over a wide range of core water contents. Presumably, a low core water content is most effective in stabilizing essential proteins in the spore core, and thus, a higher core water core results in an increased rate of inactivation of such proteins during moist heat treatment (8).

A notable observation made in this work was that C. perfringens spoVA spores were significantly more sensitive to formaldehyde, hydrogen peroxide, and nitrous acid than were wild-type spores. Previous work has shown that B. subtilis spores with or without Ca-DPA have core water contents similar to those found in this work for the corresponding C. perfringens spores (40, 68). B. subtilis spores that lack DPA are also significantly more sensitive to formaldehyde and hydrogen peroxide than wild-type spores are, although nitrous acid resistance has not been tested (40). B. subtilis spore resistance to formaldehyde, hydrogen peroxide, and nitrous acid is due in large part to the protection of spore DNA against these agents by DNA's saturation with α/β-type SASP (63). However, the levels of α/β-type SASP in DPA-less B. subtilis spores appear to be essentially identical to those in wild-type spores (40, 68), as was also the case with C. perfringens spores. Thus, the decreased resistance of DPA-less C. perfringens spores to formaldehyde, hydrogen peroxide, and nitrous acid is not due to decreased levels of α/β-type SASP. Possible explanations for this decreased resistance follow. (i) The increased hydration of the DPA-less spores allows more rapid reaction of reactive chemicals with either DNA saturated with α/β-type SASP or other targets in the spore core, such as proteins. (ii) While the levels of α/β-type SASP in the DPA-less spores are normal, a significant amount of these proteins may not be bound to the DNA because a higher core water content promotes their dissociation, a process known to take place in fully germinated B. subtilis spores that have a core water content comparable to that in growing cells (52); this protein-free DNA would then be very sensitive to DNA-damaging chemicals, as is the case in B. subtilis and C. perfringens spores (45, 49, 50, 63). Analysis of whether hydrogen peroxide kills DPA-less C. perfringens spores by DNA damage might resolve this issue, as at least with B. subtilis spores, DNA is so well protected by α/β-type SASP that this agent does not kill these spores by DNA damage, although it does cause lethal DNA damage in B. subtilis spores that lack most α/β-type SASP (57, 63). However, there have as yet been no detailed studies of the mechanism of the killing of C. perfringens spores by hydrogen peroxide or any other agent. The DPA-less C. perfringens spoVA spores were also more sensitive to HCl than wild-type spores were. HCl resistance of DPA-less B. subtilis spores has not been tested, so this is a novel observation. Since the mechanism of C. perfringens spore killing by and resistance to HCl are not known, it is difficult to explain this observation, although at least in B. subtilis spores, the α/β-type SASP are not involved in HCl resistance (63).

A third notable observation made in this work is that the DPA-less C. perfringens spoVA spores were markedly more UV sensitive than wild-type spores were. This was not seen previously with C. perfringens spores that had 15 to 20% higher core water contents but retained normal DPA levels, so perhaps sensitization to UV requires a much larger increase in core water content, as was also the case for sensitization to hydrogen peroxide (46). The major factor in the UV resistance of B. subtilis spores is the saturation of spore DNA with α/β-type SASP, and this is also important in the UV resistance of C. perfringens spores (49, 50, 60, 61, 63). Perhaps a significant amount of the C. perfringens α/β-type SASP are dissociated from the DNA in the DPA-less spores as suggested above, thus causing their decreased UV resistance. This does not appear to occur in DPA-less B. subtilis spores that have almost identical UV resistance to wild-type spores (40, 68), but perhaps the C. perfringens α/β-type SASP have significantly lower affinity for DNA than do the comparable B. subtilis proteins. While this has not been studied directly, it has been shown that one C. perfringens α/β-type SASP is less effective in restoring resistance properties to α/β-type SASP-deficient B. subtilis spores than a B. subtilis protein is, although the reason for this difference has not been established (26). In addition, the C. perfringens and B. subtilis α/β-type SASP exhibit significant differences in primary sequence, in particular in the spacing between two highly conserved regions recently shown to be crucial for the binding to and protection of DNA by a B. subtilis protein (25, 64).

One of the more surprising findings in this work was that the colony-forming efficiency of the C. perfringens spoVA spores was 20-fold lower than that of wild-type spores, although this is not the case with DPA-less B. subtilis spores (40, 68). The lower colony-forming efficiency of the C. perfringens spoVA spores was not due to inefficient spore germination, as these spores germinated as well as wild-type spores did and their viability was not increased by inclusion of lysozyme in plating medium. Thus, the majority of these spores appear to be dead. While we are not certain why this is the case, if some of the chromosome in the DPA-less C. perfringens spores is indeed not saturated with α/β-type SASP, as suggested above, perhaps this naked DNA is particularly susceptible to damage caused by endogenous agents. Indeed, while B. subtilis spores that lack either DPA or most α/β-type SASP are fully viable, the viability of B. subtilis spores that lack both DPA and α/β-type SASP is drastically reduced, and these spores die during sporulation largely due to DNA damage (58). Perhaps analysis of surviving C. perfringens spoVA spores for evidence of DNA damage, for example mutations, might clarify the reason why so many of these spores appear dead.

It was also notable that decoating of wild-type or spoVA C. perfringens spores caused a significant reduction in apparent spore viability, with this reduction being greatest for the harsher decoating regimen of treatment 1. However, these decoated spores were not dead, since their viability could be completely restored by inclusion of lysozyme in the plating medium. This result strongly suggests that the decoating treatment has removed the CLEs that degrade the C. perfringens cortex PG during spore germination, although this same decoating treatment does not remove all CLEs from B. subtilis spores. This suggests that CLEs in C. perfringens spores are located only in or adjacent to the outer edge of the cortex. The CLEs SleC and SleM, one of which (SleC) is activated by proteolysis early in germination, have been identified in and purified from C. perfringens spores, and their enzymatic activity has been characterized (7, 23, 31, 39, 65, 69). However, the roles of these proteins in vivo during spore germination have not been established, and they show little homology with the CLEs CwlJ and SleB that catalyze cortex hydrolysis during B. subtilis spore germination. Analysis of C. perfringens spores with mutations in the sleC and sleM genes should allow a better understanding of the roles of the proteins encoded by the sleC and sleM genes in spore germination and how these CLEs interact with germinant receptors and Ca-DPA.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the Army Research Office to M.R.S. and P.S. and from a fellowship from MIDEPLAN (CHILE) to D.P.-S.

We thank Nahid Sarker for her technical support.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 9 May 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Atluri, S., K. Ragkousi, D. E. Cortezzo, and P. Setlow. 2006. Cooperativity between different nutrient receptors in germination of spores of Bacillus subtilis and reduction of this cooperativity by alterations in the GerB receptor. J. Bacteriol. 18828-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Awad, M. M., A. E. Bryant, D. L. Stevens, and J. I. Rood. 1995. Virulence studies on chromosomal alpha-toxin and theta-toxin mutants constructed by allelic exchange provide genetic evidence for the essential role of alpha-toxin in Clostridium perfringens-mediated gas gangrene. Mol. Microbiol. 15191-202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bannam, T. L., and J. I. Rood. 1993. Clostridium perfringens-Escherichia coli shuttle vectors that carry single antibiotic resistance determinants. Plasmid 29233-235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bettegowda, C., X. Huang, J. Lin, I. Cheong, M. Kohli, S. A. Szabo, X. Zhang, L. A. Diaz, Jr., V. E. Velculescu, G. Parmigiani, K. W. Kinzler, B. Vogelstein, and S. Zhou. 2006. The genome and transcriptomes of the anti-tumor agent Clostridium novyi-NT. Nat. Biotechnol. 241573-1580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bruggemann, H., S. Baumer, W. F. Fricke, A. Wiezer, H. Liesegang, I. Decker, C. Herzberg, R. Martinez-Arias, R. Merkl, A. Henne, and G. Gottschalk. 2003. The genome sequence of Clostridium tetani, the causative agent of tetanus disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1001316-1321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cabrera-Martinez, R. M., F. Tovar-Rojo, V. R. Vepachedu, and P. Setlow. 2003. Effects of overexpression of nutrient receptors on germination of spores of Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 1852457-2464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen, Y., S. Miyata, S. Makino, and R. Moriyama. 1997. Molecular characterization of a germination-specific muramidase from Clostridium perfringens S40 spores and nucleotide sequence of the corresponding gene. J. Bacteriol. 1793181-3187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coleman, W. H., D. Chen, Y. Q. Li, A. E. Cowan, and P. Setlow. 2007. How moist heat kills spores of Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 1898458-8466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cowan, A. E., D. E. Koppel, B. Setlow, and P. Setlow. 2003. A soluble protein is immobile in dormant spores of Bacillus subtilis but is mobile in germinated spores: implications for spore dormancy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1004209-4214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Czeczulin, J. R., R. E. Collie, and B. A. McClane. 1996. Regulated expression of Clostridium perfringens enterotoxin in naturally cpe-negative type A, B, and C isolates of C. perfringens. Infect. Immun. 643301-3309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Duncan, C. L., and D. H. Strong. 1968. Improved medium for sporulation of Clostridium perfringens. Appl. Microbiol. 1682-89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Errington, J., S. M. Cutting, and J. Mandelstam. 1988. Branched pattern of regulatory interactions between late sporulation genes in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 170796-801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Errington, J. 1993. Bacillus subtilis sporulation: regulation of gene expression and control of morphogenesis. Microbiol. Rev. 571-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fort, P., and J. Errington. 1985. Nucleotide sequence and complementation analysis of a polycistronic sporulation operon, spoVA, in Bacillus subtilis. J. Gen. Microbiol. 1311091-1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gerhardt, P., and R. E. Marquis. 1989. Spore thermoresistance mechanisms, p. 43-63. In I. Smith, R. A. Slepecky, and P. Setlow (ed.), Regulation of procaryotic development: structural and functional analysis of bacterial sporulation and germination. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC.

- 16.Gould, G. W., and A. Hurst. 1969. The bacterial spore. Academic Press, London, United Kingdom.

- 17.Griffith, K. L., and R. E. Wolf, Jr. 2002. Measuring beta-galactosidase activity in bacteria: cell growth, permeabilization, and enzyme assay in 96-well arrays. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 290397-402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hudson, K. D., B. M. Corfe, E. H. Kemp, I. M. Feavers, P. J. Coote, and A. Moir. 2001. Localization of GerAA and GerAC germination proteins in the Bacillus subtilis spore. J. Bacteriol. 1834317-4322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Illades-Aguiar, B., and P. Setlow. 1994. Studies of the processing of the protease which initiates degradation of small, acid-soluble proteins during germination of spores of Bacillus species. J. Bacteriol. 1762788-2795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Illades-Aguiar, B., and P. Setlow. 1994. Autoprocessing of the protease that degrades small, acid-soluble proteins of spores of Bacillus species is triggered by low pH, dehydration, and dipicolinic acid. J. Bacteriol. 1767032-7037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jefferson, R. A., S. M. Burgess, and D. Hirsh. 1986. β-Glucuronidase from Escherichia coli as a gene-fusion marker. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 838447-8451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kokai-Kun, J. F., J. G. Songer, J. R. Czeczulin, F. Chen, and B. A. McClane. 1994. Comparison of Western immunoblots and gene detection assays for identification of potentially enterotoxigenic isolates of Clostridium perfringens. J. Clin. Microbiol. 322533-2539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kumazawa, T., A. Masayama, S. Fukuoka, S. Makino, T. Yoshimura, and R. Moriyama. 2007. Mode of action of a germination-specific cortex-lytic enzyme, SleC, of Clostridium perfringens S40. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 71884-892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kunst, F., N. Ogasawara, I. Moszer, A. M. Albertini, G. Alloni, V. Azevedo, M. G. Bertero, P. Bessieres, A. Bolotin, S. Borchert, R. Borriss, L. Boursier, A. Brans, M. Braun, S. C. Brignell, S. Bron, S. Brouillet, C. V. Bruschi, B. Caldwell, V. Capuano, N. M. Carter, S. K. Choi, J. J. Codani, I. F. Connerton, A. Danchin, et al. 1997. The complete genome sequence of the gram-positive bacterium Bacillus subtilis. Nature 390249-256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee, K. S., D. Bumbaca, J. Kosman, P. Setlow, and M. J. Jedrzejas. 2008. Structure of a protein-DNA complex essential for DNA protection in spores of Bacillus species. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1052806-2811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leyva-Illades, J. F., B. Setlow, M. R. Sarker, and P. Setlow. 2007. Effect of a small, acid-soluble spore protein from Clostridium perfringens on the resistance properties of Bacillus subtilis spores. J. Bacteriol. 1897927-7931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lindsay, J. A., T. C. Beaman, and P. Gerhardt. 1985. Protoplast water content of bacterial spores determined by buoyant density sedimentation. J. Bacteriol. 163735-737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Magge, A., A. Granger, P. Wahome, B. Setlow, V. Vepachedu, C. Loshon, L. Peng, D. Chen, Y.-Q. Li, and P. Setlow. 9 May 2008. Role of dipicolinic acid in the germination, stability, and viability of spores of Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. doi: 10.1128/JB.00477-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Mason, J. M., R. H. Hackett, and P. Setlow. 1988. Regulation of expression of genes coding for small, acid-soluble proteins of Bacillus subtilis spores: studies using lacZ gene fusions. J. Bacteriol. 170239-244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McClane, B. A. 2007. Clostridium perfringens, p. 423-444. In M. P. Doyle and L. R. Beuchat (ed.), Food microbiology: fundamentals and frontiers, 3rd ed. ASM Press, Washington, DC.

- 31.Miyata, S., R. Moriyama, N. Miyahara, and S. Makino. 1995. A gene (sleC) encoding a spore-cortex-lytic enzyme from Clostridium perfringens S40 spores; cloning, sequence analysis and molecular characterization. Microbiology 1412643-2650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miyata, S., S. Kozuka, Y. Yasuda, Y. Chen, R. Moriyama, K. Tochikubo, and S. Makino. 1997. Localization of germination-specific spore-lytic enzymes in Clostridium perfringens S40 spores detected by immunoelectron microscopy. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 152243-247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moir, A., and D. A. Smith. 1990. The genetics of bacterial spore germination. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 44531-553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moir, A., B. M. Corfe, and J. Behravan. 2002. Spore germination. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 59403-409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Murrell, W. G., and A. D. Warth. 1965. Composition and heat resistance of bacterial spores, p. 1-12. In L. L. Campbell and H. O. Halvorson (ed.), Spore III. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC.

- 36.Murrell, W. G. 1967. The biochemistry of the bacterial endospore. Adv. Microbiol. Physiol. 1133-251. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Myers, G. S., D. A. Rasko, J. K. Cheung, J. Ravel, R. Seshadri, R. T. DeBoy, Q. Ren, J. Varga, M. M. Awad, L. M. Brinkac, S. C. Daugherty, D. H. Haft, R. J. Dodson, R. Madupu, W. C. Nelson, M. J. Rosovitz, S. A. Sullivan, H. Khouri, G. I. Dimitrov, K. L. Watkins, S. Mulligan, J. Benton, D. Radune, D. J. Fisher, H. S. Atkins, T. Hiscox, B. H. Jost, S. J. Billington, J. G. Songer, B. A. McClane, R. W. Titball, J. I. Rood, S. B. Melville, and I. T. Paulsen. 2006. Skewed genomic variability in strains of the toxigenic bacterial pathogen, Clostridium perfringens. Genome Res. 161031-1040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nölling, J., G. Breton, M. V. Omelchenko, K. S. Makarova, Q. Zeng, R. Gibson, H. M. Lee, J. Dubois, D. Qiu, J. Hitti, Y. I. Wolf, R. L. Tatusov, F. Sabathe, L. Doucette-Stamm, P. Soucaille, M. J. Daly, G. N. Bennett, E. V. Koonin, and D. R. Smith. 2001. Genome sequence and comparative analysis of the solvent-producing bacterium Clostridium acetobutylicum. J. Bacteriol. 1834823-4838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Okamura, S., K. Urakami, M. Kimata, T. Aoshima, S. Shimamoto, R. Moriyama, and S. Makino. 2000. The N-terminal prepeptide is required for the production of spore cortex-lytic enzyme from its inactive precursor during germination of Clostridium perfringens S40 spores. Mol. Microbiol. 37821-827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Paidhungat, M., B. Setlow, A. Driks, and P. Setlow. 2000. Characterization of spores of Bacillus subtilis which lack dipicolinic acid. J. Bacteriol. 1825505-5512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Paidhungat, M., and P. Setlow. 2000. Role of Ger proteins in nutrient and nonnutrient triggering of spore germination in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 1822513-2519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Paidhungat, M., K. Ragkousi, and P. Setlow. 2001. Genetic requirements for induction of germination of spores of Bacillus subtilis by Ca2+-dipicolinate. J. Bacteriol. 1834886-4893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Paidhungat, M., and P. Setlow. 2001. Localization of a germinant receptor protein (GerBA) to the inner membrane of Bacillus subtilis spores. J. Bacteriol. 1833982-3990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Paidhungat, M., B. Setlow, W. B. Daniels, D. Hoover, E. Papafragkou, and P. Setlow. 2002. Mechanisms of induction of germination of Bacillus subtilis spores by high pressure. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 683172-3175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Paredes-Sabja, D., D. Raju, J. A. Torres, and M. R. Sarker. 2008. Role of small, acid-soluble spore proteins in the resistance of Clostridium perfringens spores to chemicals. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 122333-335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Paredes-Sabja, D., N. Sarker, B. Setlow, P. Setlow, and M. R. Sarker. 2008. Roles of DacB and Spm proteins in Clostridium perfringens spore resistance to moist heat, chemicals, and UV radiation. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 743730-3738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Paredes-Sabja, D., J. A. Torres, P. Setlow, and M. R. Sarker. 2008. Clostridium perfringens spore germination: characterization of germinants and their receptors. J. Bacteriol. 1901190-1201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Popham, D. L., S. Sengupta, and P. Setlow. 1995. Heat, hydrogen peroxide, and UV resistance of Bacillus subtilis spores with increased core water content and with or without major DNA-binding proteins. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 613633-3638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Raju, D., M. Waters, P. Setlow, and M. R. Sarker. 2006. Investigating the role of small, acid-soluble spore proteins (SASPs) in the resistance of Clostridium perfringens spores to heat. BMC Microbiol. 650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Raju, D., P. Setlow, and M. R. Sarker. 2007. Antisense-RNA-mediated decreased synthesis of small, acid-soluble spore proteins leads to decreased resistance of Clostridium perfringens spores to moist heat and UV radiation. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 732048-2053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rotman, Y., and M. L. Fields. 1968. A modified reagent for dipicolinic acid analysis. Anal. Biochem. 22168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sanchez-Salas, J. L., M. L. Santiago-Lara, B. Setlow, M. D. Sussman, and P. Setlow. 1992. Properties of Bacillus megaterium and Bacillus subtilis mutants which lack the protease that degrades small, acid-soluble proteins during spore germination. J. Bacteriol. 174807-814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sanchez-Salas, J. L., and P. Setlow. 1993. Proteolytic processing of the protease which initiates degradation of small, acid-soluble proteins during germination of Bacillus subtilis spores. J. Bacteriol. 1752568-2577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sarker, M. R., R. J. Carman, and B. A. McClane. 1999. Inactivation of the gene (cpe) encoding Clostridium perfringens enterotoxin eliminates the ability of two cpe-positive C. perfringens type A human gastrointestinal disease isolates to affect rabbit ileal loops. Mol. Microbiol. 33946-958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sarker, M. R., R. P. Shivers, S. G. Sparks, V. K. Juneja, and B. A. McClane. 2000. Comparative experiments to examine the effects of heating on vegetative cells and spores of Clostridium perfringens isolates carrying plasmid genes versus chromosomal enterotoxin genes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 663234-3240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 56.Sebaihia, M., B. W. Wren, P. Mullany, N. F. Fairweather, N. Minton, R. Stabler, N. R. Thomson, A. P. Roberts, A. M. Cerdeno-Tarraga, H. Wang, M. T. Holden, A. Wright, C. Churcher, M. A. Quail, S. Baker, N. Bason, K. Brooks, T. Chillingworth, A. Cronin, P. Davis, L. Dowd, A. Fraser, T. Feltwell, Z. Hance, S. Holroyd, K. Jagels, S. Moule, K. Mungall, C. Price, E. Rabbinowitsch, S. Sharp, M. Simmonds, K. Stevens, L. Unwin, S. Whithead, B. Dupuy, G. Dougan, B. Barrell, and J. Parkhill. 2006. The multidrug-resistant human pathogen Clostridium difficile has a highly mobile, mosaic genome. Nat. Genet. 38779-786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Setlow, B., and P. Setlow. 1993. Binding of small, acid-soluble spore proteins to DNA plays a significant role in the resistance of Bacillus subtilis spores to hydrogen peroxide. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 593418-3423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Setlow, B., S. Atluri, R. Kitchel, K. Koziol-Dube, and P. Setlow. 2006. Role of dipicolinic acid in resistance and stability of spores of Bacillus subtilis with or without DNA-protective α/β-type small acid-soluble proteins. J. Bacteriol. 1883740-3747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Setlow, P. 1983. Germination and outgrowth, p. 211-254. In A. Hurst and G. W. Gould (ed.), The bacterial spore, vol. II. Academic Press, London, United Kingdom. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Setlow, P. 1988. Small, acid-soluble spore proteins of Bacillus species: structure, synthesis, genetics, function, and degradation. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 42319-338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Setlow, P. 1994. Mechanisms which contribute to the long-term survival of spores of Bacillus species. Soc. Appl. Bacteriol. Symp. Ser. 2349S-60S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Setlow, P. 2003. Spore germination. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 6550-556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Setlow, P. 2006. Spores of Bacillus subtilis: their resistance to and killing by radiation, heat and chemicals. J. Appl. Microbiol. 101514-525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Setlow, P. 2007. I will survive: DNA protection in bacterial spores. Trends. Microbiol. 15172-180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Shimamoto, S., R. Moriyama, K. Sugimoto, S. Miyata, and S. Makino. 2001. Partial characterization of an enzyme fraction with protease activity which converts the spore peptidoglycan hydrolase (SleC) precursor to an active enzyme during germination of Clostridium perfringens S40 spores and analysis of a gene cluster involved in the activity. J. Bacteriol. 1833742-3751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sloan, J., T. A. Warner, P. T. Scott, T. L. Bannam, D. I. Berryman, and J. I. Rood. 1992. Construction of a sequenced Clostridium perfringens-Escherichia coli shuttle plasmid. Plasmid 27207-219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sussman, M. D., and P. Setlow. 1991. Cloning, nucleotide sequence, and regulation of the Bacillus subtilis gpr gene, which codes for the protease that initiates degradation of small, acid-soluble proteins during spore germination. J. Bacteriol. 173291-300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tovar-Rojo, F., M. Chander, B. Setlow, and P. Setlow. 2002. The products of the spoVA operon are involved in dipicolinic acid uptake into developing spores of Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 184584-587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Urakami, K., S. Miyata, R. Moriyama, K. Sugimoto, and S. Makino. 1999. Germination-specific cortex-lytic enzymes from Clostridium perfringens S40 spores: time of synthesis, precursor structure and regulation of enzymatic activity. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 173467-473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Vepachedu, V. R., and P. Setlow. 2004. Analysis of the germination of spores of Bacillus subtilis with temperature sensitive spo mutations in the spoVA operon. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 23971-77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Vepachedu, V. R., and P. Setlow. 2005. Localization of SpoVAD to the inner membrane of spores of Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 1875677-5682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Vepachedu, V. R., and P. Setlow. 2007. Role of SpoVA proteins in release of dipicolinic acid during germination of Bacillus subtilis spores triggered by dodecylamine or lysozyme. J. Bacteriol. 1891565-1572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Yingst, D. R., and J. F. Hoffman. 1983. Intracellular free Ca and Mg of human red blood cell ghosts measured with entrapped arsenazo III. Anal. Biochem. 132431-448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zhao, Y., and S. B. Melville. 1998. Identification and characterization of sporulation-dependent promoters upstream of the enterotoxin gene (cpe) of Clostridium perfringens. J. Bacteriol. 180136-142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]