Abstract

Shiga toxins (Stx) are the main virulence factors associated with a form of Escherichia coli known as Shiga toxin-producing E. coli (STEC). They are encoded in temperate lambdoid phages located on the chromosome of STEC. STEC strains can carry more than one prophage. Consequently, toxin and phage production might be influenced by the presence of more than one Stx prophage on the bacterial chromosome. To examine the effect of the number of prophages on Stx production, we produced E. coli K-12 strains carrying either one Stx2 prophage or two different Stx2 prophages. We used recombinant phages in which an antibiotic resistance gene (aph, cat, or tet) was incorporated in the middle of the Shiga toxin operon. Shiga toxin was quantified by immunoassay and by cytotoxicity assay on Vero cells (50% cytotoxic dose). When two prophages were inserted in the host chromosome, Shiga toxin production and the rate of lytic cycle activation fell. The cI repressor seems to be involved in incorporation of the second prophage. Incorporation and establishment of the lysogenic state of the two prophages, which lowers toxin production, could be regulated by the CI repressors of both prophages operating in trans. Although the sequences of the cI genes of the phages studied differed, the CI protein conformation was conserved. Results indicate that the presence of more than one prophage in the host chromosome could be regarded as a mechanism to allow genetic retention in the cell, by reducing the activation of lytic cycle and hence the pathogenicity of the strains.

Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli (STEC) strains are considered food- and waterborne pathogens, although person-to-person transmission has also been reported (25, 35). STEC strains cause bloody diarrhea and hemolytic-uremic syndrome and can lead to severe complications (35, 37, 49). One of the best known serotypes is O157:H7, which is the most common virulent serogroup in the United States and Canada, while other serotypes are frequently reported in European outbreaks (4, 49). STEC strains are normally found in cattle, goat, and sheep (5), which act as a reservoir, releasing STEC in their feces.

Shiga toxins (Stx) are the main virulence factors in STEC. They are highly related to the toxin produced by Shigella dysenteriae serotype I (36). Currently, two Stx have been described: Stx1 and Stx2, along with their variants (22). Some of these subtypes are found only in certain reservoirs (14). Generally, Shiga toxins are characterized by their hexameric conformation. They are formed by five B subunits, which allow toxin attachment to their enterocyte receptor; Gb3, which is also present in endothelial cells of glomerular capillaries (21); and one A subunit, which is catalytically active and blocks translation of mRNA to protein, leading to cell death (14).

Shiga toxins are encoded in the genomes of temperate phages (19). They are considered members of the lambdoid family, since they share a common genome arrangement that conserves the relative positions of the genes with similar activities and associated regulatory signals (7). Although Shiga toxin-encoding bacteriophages are a heterogeneous group in terms of morphology and their genetic organization (24, 33, 46, 54), the location of stx genes is conserved, being found next to the lytic genes and downstream of the Q antiterminator (36). Therefore, Shiga toxin production is basically linked to the induction or progression of the phage lytic cycle after activation of the SOS response in the bacterial host. The toxin is released through cell lysis (55). Following the lytic burst, Stx phages act as vectors in the stx horizontal transmission to other members of the family Enterobacteriaceae (1, 2, 19, 33, 44, 46, 51).

Previous studies with STEC O157:H7 strains isolated from a single outbreak showed that isolates harboring two different Stx prophages produced less toxin than strains from the same clone carrying only one Stx prophage (34). In accordance with other authors (20), we hypothesized that the expression of phage genes may be regulated when other temperate phages are present. We examined in an E. coli K-12 background the effect on phage and toxin production when the same host strain was converted by one or two Stx prophages. We also identified the genes implicated in the acquisition of a second prophage.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, bacteriophages, and growing conditions.

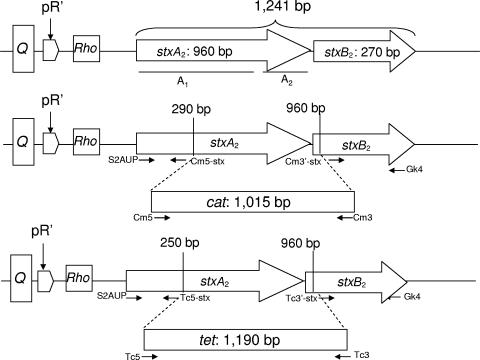

The bacteriophages, strains, and plasmids used in this study are described in Table 1. Phages ΦA9, ΦA75, ΦA312, ΦA534, ΦA549, Φ557, and ΦVTB55 were obtained from STEC isolated from cattle. They were characterized in previous studies (2, 33, 44, 45, 46). Characterization included analysis of morphology and host infectivity. Moreover, genetic characterization comprised the determination of their genome size, restriction fragment length polymorphism and location of stx2 in the restricted phage DNA, sequences of the stx2 and integrase genes, and insertion sites used to integrate within the chromosomes of different host strains. These phages were used to convert laboratory E. coli strains generating lysogens carrying one Shiga toxin-encoding prophage (Stx prophage). This set of phages and phage 933W were modified by the incorporation of an antibiotic resistance gene (cat and/or tet) in the middle of the stx2 genes (Fig. 1) using the Red recombinase system as described previously (45).

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains, bacteriophages, and plasmids used in this study

| Bacterial strain, lysogen, phage, or plasmid | Characteristic(s) | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Bacterial strains | ||

| Shigella sonnei 866 | Used as host strain | 33 |

| E. coli C600 | Used as host strain | 57 |

| E. coli LMG194 | Used for evaluation of CI expression | Invitrogen |

| E. coli TOP10 | Used for evaluation of CI expression | Invitrogen |

| Lysogens | ||

| E. coli MC1061(Φ24B) | Lysogen of phage Φ24B | 2 |

| E. coli C600(Φ3538) | Lysogen of phage Φ3538 | 44 |

| E. coli C600(933W) | Lysogen of phage 933W | 36 |

| LysΦA9, LysΦA9Tc, LysΦA9Cm, LysΦA75, LysΦA75Tc, LysΦA75Cm, LysΦA312, LysΦA312Tc, LysΦA312Cm, LysΦA534, LysΦA534Tc, LysΦA534Cm, LysΦA549, LysΦA549Tc, LysΦA549Cm, LysΦA557, LysΦA557Tc, LysΦA557Cm, LysΦVTB55, LysΦVTB55Tc, and LysΦVTB55Cm | E. coli lysogens harboring Stx phages and the recombinant phages described below | 46 |

| Lys933WΔcro | Lysogen C600(933W) derivative containing the cro gene replaced by a cat gene | This study |

| Lys933WΔcIΔcro | Lysogen C600(933W) derivative containing the fragment between the cI and cro genes replaced by a tet gene | This study |

| Phages | ||

| ΦA9, ΦA75, ΦA312, ΦA534, ΦA549, ΦA557, and ΦVTB55 | Stx phages previously induced from STEC strains and serotypes O157:H7 and O2:H27 isolated from cattle | 33 |

| ΦA9Tc, ΦA9Cm, ΦA75Tc, ΦA75Cm, ΦA312Tc, ΦA312Cm, ΦA534Tc, ΦA534Cm, ΦA549Tc, ΦA549Cm, ΦA557Tc, ΦA557Cm ΦVTB55Tc, and ΦVTB55Cm | Stx phage derivatives containing a fragment of the stx2 operon replaced by an antibiotic resistance gene (tet or cat) | 46 |

| 933W | Reference Stx2 bacteriophage | 36 |

| 933WTc and 933WCm | 933W phage derivative containing the stx2 operon replaced by the tet gene (in 933WTc) or cat gene (in 933WCm) | 45 |

| Φ24B | Δstx2::aph | 2 |

| Φ3538 | Δstx2::cat | 44 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pGEM-T Easy | Vector used for complementation experiments | Promega |

| pGcI | pGEM-T Easy harboring a 879-bp band containing the cI gene | This study |

| pGcI-cro | pGEM-T Easy harboring a 1,017-bp band containing the fragment between cI and cro | This study |

| pGcro | pGEM-T Easy harboring a 287-bp band containing the cro gene | This study |

| pKD46 | Plasmid with the Red recombinase system | 10 |

| pACYC184 | Plasmid carrying the tet gene for tetracycline resistance | 40 |

| pKD3 | Plasmid carrying the cat gene for chloramphenicol resistance | 10 |

| pBAD-TOPO | pBAD-TOPO vector | Invitrogen |

| pBAD::cI | pBAD-TOPO vector carrying a 711-bp fragment (cI gene) downstream of the pBAD promoter | This study |

FIG. 1.

Schematic map of the generation of the recombinant phages (cat or tet) harboring the antibiotic resistance genes in the stx gene, indicating the precise positions where the cassettes were incorporated, the sizes of fragments replaced by the antibiotic cassettes, and the primers used to generate the fragments.

Bacterial strains (Table 1) were grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth and on LB agar. The LB medium was supplemented with kanamycin (50 μg ml−1), chloramphenicol (30 and 5 μg ml−1), and tetracycline (5 μg ml−1) when needed.

Preparation of digoxigenin-labeled gene probes.

DNA fragments of the stxA2, tet (tetracycline resistance), cat (chloramphenicol resistance), and aph (kanamycin resistance) genes were produced by amplification with the respective primers (Table 2), labeled with digoxigenin, and used as probes as previously described (33). The aph, tet, and cat probes hybridize only with the recombinant phages, while the stxA2 probe detects only the Stx2 phages, since this fragment is replaced by the antibiotic resistance gene in the recombinant phages.

TABLE 2.

Oligonucleotides used in this study

| Primer | Sequencea | Gene region | Size (bp) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UP 378 | GCGTTTTGACCATCTTCGT | 378-bp fragment | 378 | 32 |

| LP 378 | ACAGGAGCAGTTTCAGACAG | stxA2 | 378 | 32 |

| S2Aup | ATGAAGTGTATATTATTTA | stxA2 (A subunit) | 979 | 34 |

| S2Alp | TTCTTCATGCTTAACTCCT | stxA2 (A subunit) | 979 | 34 |

| GK3 | ATGAAGAAGATGTTTATG | stxB2 (B subunit) | 230 | 41 |

| GK4 | TCAGTCATTATTAAACTG | stxB2 (B subunit) | 230 | 41 |

| Q up | ATACACTGGCGATAAAGAAG | Antiterminator Q | 34 | |

| Cm-5 | TGTGTAGGCTGGAGCTGCTTC | cat gene (Cmr) | 1,015 | 45 |

| Cm-3 | CATATGAATATCCTCCTTAG | cat gene (Cmr) | 1,015 | 45 |

| Tc-5 | TCAGCCCCATACGATATAAG | tet gene (Tcr) | 1,190 | 45 |

| Tc-3 | TGGAGTGGTGAATCCGTTAG | tet gene (Tcr) | 1,190 | 45 |

| Km-5 | GTCAGCGTAATGCTCTGC | aph gene (Kmr) | 897 | This study |

| Km-3 | GTCTGCTTACATAAACAG | aph gene (Kmr) | 897 | This study |

| Rho | ATATCTGCGCCGGGTCTG | rho gene upstream of stxA2 | 45 | |

| cm5-stx | GAAGCAGCTCCAGCCTACACAACGAAGATGGTCAAAACGCG | Generation of stx-cat phages | This study | |

| cm3′-stx | CTAAGGAGGATATTCATATGATTAGTTTCTGTTAATGCA | Generation of stx-cat phages | This study | |

| Tc5-stx | CTTATATCGTATGGGGCTGAACGAAGATGGTCAAAACGCG | Generation of stx-tet phages | This study | |

| Tc3′-stx | CTAACGGATTCACCACTCCAATTAGTTTCTGTTAATGCA | Generation of stx-cat phages | This study | |

| cro-up | ATGCAAAATCTTGATGAGCCGATTAAAGGTGTCGG | cro gene of 933W | 228 | This study |

| cro-lp | TTATGCAGCCAGAAGGTTCTTTTTGCTTATTTCAAG | cro gene of 933W | 228 | This study |

| cro-cm5 | GAAGCAGCTCCAGCCTACACAGAGCCACTTATAGACAGC | Generation of cro mutant | 93 | This study |

| cro-cm3 | CTAAGGAGGATATTCATATGAAACTAAATACGCATCAA | Generation of cro mutant | 97 | This study |

| cro-ext | CGCTTTGTCAGCGACGTA | Confirmation of cro mutant | 950 | This study |

| cI-up | GTCACGAACTTTTCAGCACT | cI gene of 933W | 710 | This study |

| cI-lp | ATGGTTCAGAATGAAAAAGT | cI gene of 933W | 710 | This study |

| cI-tc5 | CTTATATCGTATGGGGCTGAAACATGATTAAGGTTCTTGG | Generation of cro-cI mutant | 187 | This study |

| cro-tc3 | CTAACGGATTCACCACTCCAAAACTAAATACGCATCAA | Generation of cro-cI mutant | 97 | This study |

| cI ext | TCATTGAACGCCATCTAT | Confirmation of cro-cI mutant | 462 | This study |

| cI2-up | CCTGACGGGATGTTAATTCTGGTTGACCCTGAGCAAG | Short fragment of the cI gene | 219 | This study |

| cI2-lp | TCTTCAGGCCATTGGCTGGCGGATAACTTTCCCACAACG | Short fragment of the cI gene | 219 | This study |

| oR1lp | GAGCCACTTATAGACAGC | Generation of cI pR fragment | 809 | This study |

| pGEMT7 up | TGTAATACGACTCACTAT | Confirmation of pGEM constructs | This study | |

| pBADf | ATGCCATAGCATTTTTATCC | Confirmation of pBAD::cI | Invitrogen | |

| pBADr | GATTTAATCTGTATCAGG | Confirmation of pBAD::cI | Invitrogen |

The sequence corresponding to the target gene is underlined.

Hybridization techniques.

Colony and plaque blot analyses were performed with Nylon-N+ membranes (Hybond N+; Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Barcelona, Spain) (42). Colony hybridization was performed as previously described (17). Stringent hybridization was achieved with the DIG DNA detection kit (Roche Diagnostics, Barcelona, Spain) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The digoxigenin-labeled probes were prepared as described above.

PCR techniques.

PCRs were performed with a GeneAmp PCR system 2400 (Applied Biosystems, Barcelona, Spain). Purified DNA (0.5 ng) was used for PCR amplification. The oligonucleotides used in this study are described in Table 2.

Reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR).

Total RNA was isolated using the Qiagen RNeasy RNA isolation kit (Qiagen Inc., Valencia, CA) according to the manufacturer's guidelines. RNA was quantified using a NanoDrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer (Bonsai Technologies, Barcelona, Spain). To asses the RNA purity, samples were incubated with RQ1 RNase-free DNase (Promega Co., Madison, WI) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Total RNA (5 μg) was used for one-step RT-PCR using illustra Ready-To-Go RT-PCR beads (GE Health Care Life Sciences, Barcelona, Spain) following the manufacturer's instructions.

Sequencing techniques and bioinformatics.

The identity of each PCR product was confirmed by sequencing. The oligonucleotides used for sequencing are described in Table 2. Sequencing was performed with an ABI PRISM Big Dye 3.1 terminator cycle sequencing ready reaction kit and an ABI PRISM 3700 DNA analyzer (both from Applied Biosystems, Barcelona, Spain), according to the manufacturer's instructions. All sequences were performed in duplicate.

Nucleotide sequence analysis searches for homologous DNA sequences in the EMBL and GenBank database libraries were performed with the Wisconsin Package version 10.2, Genetics Computer Group (GCG), Madison, WI. BLAST analyses and protein conformation studies were done with the tools available on the website http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov.

Generation of the lysogens 933WΔcro::cat and 933WΔcIΔcro::tet.

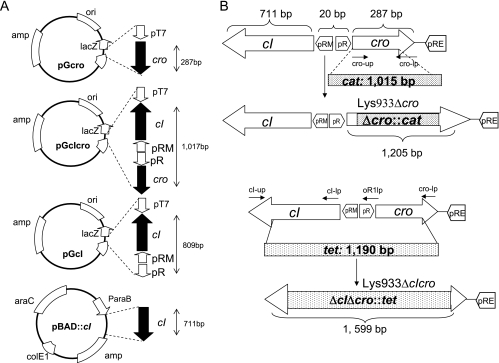

Figure 2 shows the mutations incorporated in the cro and cI-cro genes as well as the fragment sizes of cI and cI-cro genes used in the complementation experiments. Mutants were obtained using a Red recombinase method modified as previously described (45).

FIG. 2.

Generation of Lys933WΔcro::cat and Lys933WΔcIΔcro::tet strains. Schematic map of the E. coli 933W cro-cI locus indicating the positions of the promoters and the cro and cI genes. (A) Schematic diagram of plasmids pGcro, pGcIcro, pGcI and pBAD::cI indicating the orientation of the genes and promoters. (B) Sizes of the genes and substitution by the antibiotic cassettes to construct the mutants Lys933Δcro and Lys933ΔcIΔcro.

To generate Lys933WΔcro::cat, the cro-up/cro-cm5 primer pair (Table 2) was used to generate a 5′ fragment of 93 bp comprising the initial codon of cro to a 5′ region of the cat gene. The cro-lp/cro-cm3 primer pair was used to give a fragment of 97 bp comprising the last codon of cro and the 3′ cat region. The Cm-5/Cm-3 primer pair was used to obtain the 1,015-bp cat fragment. The three PCR products were annealed and amplified using cro-up and cro-lp primers to give a PCR product containing two flanking regions of homology to cro and containing the cat gene. This linear PCR product was transformed into the lysogen 933W carrying the pKD46 plasmid as described previously (45). Recombination between the cro gene and the fragment was confirmed by PCR and sequencing using the external cro primer together with the Cm-5 primer (Table 2).

Strain Lys933WΔcIΔcro::tet was obtained in a similar way. The cI-up/cI-tc5 primer pair was used to generate a 187-bp fragment comprising the initial codon of cI and the 5′ region of the tet gene. The cro-lp/cro-tc3 primer pair was used to obtain a 97-bp fragment which comprises the last codon of cro and the 3′ region of the tet gene. Tc-5 and Tc-3 primers generated the 1,190-bp fragment of the tet gene. The three PCR products were used as templates to generate a linear fragment containing the tet gene with two flanking regions of homology to the cI and cro genes. The fragment was transformed into lysogen 933W as described above, and recombination was confirmed using external cI and cro primers (Table 2) by PCR and sequencing.

Strain Lys933WΔcro:cat was infected with Δstx2::tet recombinant phages, while lysogen Lys933WΔcIΔcro::tet was infected with Δstx2::cat recombinant phages as described in the corresponding section. Experiments to incorporate a second prophage were performed at least three independent times. Strains C600 (933W) and C600 were used as controls.

Complementation with cro and cI.

Complementation experiments were carried out using plasmid pGEM-T Easy in which cI-pRM, cro, and the fragment comprising cI-cro (Fig. 2) were also cloned as the manufacturer indicated (Promega Co., Madison, WI), generating pGcro, pGcIcro, and pGcI (Table 1). The correct orientation was confirmed by PCR and sequencing.

To investigate how different cI expression can affect generation of double mutants, the cI gene (without promoter) was cloned using a pBAD-TOPO TA expression kit, which contains a pBAD-TOPO vector that allows insertion of the gene under the control of an araBAD promoter (Invitrogen Corporation, Barcelona, Spain). Insertion of cI was done following the instructions of the manufacturer. The construct was transformed in E. coli One Shot TOP10 competent cells as described by the manufacturer. In the resulting construct, pBAD::cI, cI gene was positioned immediately downstream of the Para inducible promoter in the correct orientation, as confirmed by PCR and sequencing (Fig. 2).

Regulation of cI expression using pBAD::cI.

The pBAD::cI construct described above was isolated from E. coli TOP10 cells and transformed by electroporation into E. coli strain LMG194 (Table 1) used for control of pBAD expression, C600, and Lys933WΔcIΔcro. The expression of cI was optimized by adding arabinose to the medium at different final concentrations (ranging from 0 to 0.2%) as described by the manufacturer (Invitrogen Corporation, Barcelona, Spain). Results were visualized by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis analysis and Coomassie blue staining. The optimum concentration of arabinose required for maximum expression of the CI protein was found to be 0.2%.

Arabinose (0.002% and 0.2%) were finally used to evaluate whether there were differences in the incorporation of a second prophage in the mutant strain harboring the pBAD::cI construct at two levels of CI expression. The recombinant phages were used for infection of the mutant strain harboring pBAD::cI as described above. Strains C600(933W) and C600 containing pBAD::cI or pBAD without cI were included as controls.

Incorporation of a second prophage in lysogens carrying a Stx prophage.

To obtain E. coli strains carrying two Stx2 phages, E. coli K-12 lysogens of each Stx phage were used (33, 46). Phage suspensions of the recombinant Stx2 phages (including Φ3538 and Φ24B) containing from 107 to 108 PFU ml−1were used to infect a culture of the respective lysogen (109 CFU ml−1) to be further converted. The mixture was then incubated and plated onto LB agar with the respective antibiotic. The incorporation of the two prophages (stx and tet, stx and cat, or stx and aph) in the lysogens was checked by colony hybridization and confirmed by a single PCR (46).

To establish the immunity profiles of the Stx2 phages studied, their abilities to produce plaques and to convert the lysogens carrying one Stx prophage were evaluated. The plaque assay was performed as described previously (34) using Shigella sonnei 866 as the host, and plaques were hybridized with the appropriate probe to check that the lytic effect was caused by the Stx2 phage or the recombinant phage.

Evaluation of toxin production.

The differences in toxin production between the E. coli strains harboring one Stx prophage and those harboring two prophages were determined. For this purpose, bacteria were grown from single colonies in LB at 37°C to the exponential growth phase (3 × 108 CFU ml−1). At this point, mitomycin C was added (0.5 μg·ml−1) for lytic cycle induction, and bacteria were then incubated at 37°C for 18 h. The cultures were analyzed with a spectrophotometer set at 600 nm every 2 h after the addition of mitomycin C. The optical density was compared with a control of the same culture without mitomycin C. After 18 h of incubation, the supernatant of each culture was filter sterilized and analyzed for the presence of Stx2 by both enzyme immunoassay and Vero cell assay. The enzyme immunoassay (Premier EHEC; Meridian Diagnostics Inc., Cincinnati, OH) was used to determine the concentration of Stx2 produced by the lysogens. Dilution of each sample was tested as described by the manufacturer, and results were compared to a standard curve constructed with purified Stx2 (Toxin Technology, Inc., Sarasota, FL). Results obtained were analyzed spectrophotometrically at two wavelengths (450 and 630 nm) and processed as indicated by the manufacturer.

Cytotoxicity assays were done on Vero cells (30). Serial dilutions of the supernatants of the lysogens, obtained as described above, were incubated with 4 × 104 Vero cells ml−1 at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. Purified Stx2 from Toxin Technology, Inc. (Sarasota, FL) served as a positive control. Cells were incubated for 72 h and evaluated every 12 h. The amount of toxin contained in the last 10-fold dilution of the sample in which ≥50% of the Vero cells detached from the plastic, as assessed by direct microscope observation and confirmed by A620, was considered to be the 50% cytotoxic dose (CD50) (56).

To discard the possibility that the diminished Stx expression observed in lysogens harboring truncated phages or both phages was a transport problem from the cell, some experiments were performed with sonicated cultures. For this purpose, the cultures were sonicated at 50% power for a total of 3 min in 15-s bursts with a model 300 sonic dismembrator (Fisher Bioblock Scientific, Strasbourg, France). Sonic lysates were clarified by centrifugation at 8,000 × g for 10 min, filter sterilized as described above, and used for evaluation of cytotoxicity onto Vero cells.

E. coli O157:H7 strain ATCC 43889 and E. coli C600 carrying a 933W prophage were used as Stx-producing controls. E. coli O157:H7 strain ATCC 43888, E. coli K-12 strain C600, LB broth with mitomycin C (0.5 μg·ml−1), and phosphate-buffered saline were used as negative controls.

RESULTS

Generation of E. coli strains harboring two Shiga toxin-encoding prophages.

A group of previously characterized Stx phages was used to produce laboratory lysogens (Table 1). To generate lysogens carrying two Stx prophages, a second recombinant Stx prophage was used to infect these laboratory lysogens. Recombinant prophages were generated by the incorporation of an antibiotic resistance gene (cat or tet) (Table 1 and Fig. 1) that replaced a 670-bp central fragment of the Shiga toxin operon. The presence of the antibiotic resistance gene allowed selection of lysogens carrying the recombinant prophage. In addition, the insertion of the cat or tet gene within the stx operon produced a fragment of different length than the intact stx operon did (1,526 bp for cat recombinants or 1,701 bp for tet compared with the 1,241 bp of the intact stx2). This difference in fragment length could be used to distinguish the Stx phage from the recombinant prophage when amplified using primers (Table 2) from the 5′ and 3′ ends of the stx2 operon, allowing identification of lysogens carrying two prophages when two bands were observed (46).

After the infection of a lysogen carrying one Stx prophage by a second incoming phage (Δstx::cat or Δstx::tet), the most common event was the incorporation of the second phage in a secondary insertion site of the host chromosome (46) (Table 3). Incorporation of a second prophage generated more lysogens (from 0.5 to 1.5 logarithmic units more) than the control case (the host strain lysogenized only by the recombinant prophage). This observation was confirmed in the independent replicate experiments, in all of which the differences were significant (P value of <0.05). The number of colonies of lysogens carrying only one Stx phage exceeded those carrying two phages in only 3 cases out of 80 (Table 3). In those cases in which two prophages coexisted in the same strain, recombination between phages was not observed, nand they were not integrated in tandem. The two prophages occupied different insertion sites in the host chromosome, and both produced separate viral particles, which converted new host strains independently (46). Together with the incorporation of the second prophage, we also observed that insertion of the second recombinant prophage but loss of the first Stx phage also occurred frequently. In this study, this phenomenon has been named phage substitution or “heteroimmune curing” (46, 48). Only in a few cases did infection with the second phage fail to occur.

TABLE 3.

Comparison of the number of lysogens generated when the incoming phage infects a lysogen (Lys) already harboring one Stx prophage versus the number of lysogens generated when the same incoming phage infects E. coli K-12 (prophage-free)

| Incoming phage | No. of replicate exptsa | Comparison in the no. of lysogens (Lys) with one Stx prophage (log CFU·ml−1) versus the no. of lysogens (log CFU·ml−1) generated when the same incoming phage infects E. coli K-12b

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LysΦA9 vs K-12 | LysΦA75 vs K-12 | LysΦ312 vs K-12 | LysΦ534 vs K-12 | LysΦ549 vs K-12 | LysΦ557 vs K-12 | LysΦVTB55 vs K-12 | LysΦ933W vs K-12 | ||

| ΦA9 | 5 | NI | 6.23 vs 5.05 | PS | 6.80 vs 5.74 | PS | PS | 7.55 vs 6.28 | 7.74 vs 7.10 |

| ΦA75 | 4 | 7.55 vs 6.08 | NI | PS | PS | PS | PS | NI | 7.54 vs 6.08 |

| ΦA312 | 4 | 8.13 vs 8.22 | PS | PS | 6.75 vs 6.95 | PS | PS | NI | 8.20 vs 8.22 |

| ΦA534 | 4 | NI | 5.85 vs 1.92 | PS | 5.01 vs 1.92 | 2.73 vs 1.69 | 3.56 vs 1.92 | NI | 6.79 vs 5.87 |

| ΦA549 | 4 | 8.51 vs 7.24 | 7.71 vs 6.89 | PS | PS | 7.69 vs 6.89 | PS | NI | 7.96 vs 7.24 |

| ΦA557 | 4 | 8.04 vs 7.63 | 5.87 vs 5.88 | 6.23 vs 5.88 | 7.29 vs 5.88 | PS | PS | 3.29 vs 5.88 | 8.25 vs 7.63 |

| ΦVTB55 | 4 | 4.89 vs 3.21 | PS | PS | PS | PS | PS | NI | 5.92 vs 3.21 |

| 933W | 6 | 8.34 vs 7.73 | 6.88 vs 6.35 | PS | 7.25 vs 6.35 | PS | PS | NI | 8.35 vs 7.73 |

| Φ3538 | 6 | 7.97 vs 7.38 | 5.47 vs 3.38 | 3.88 vs 3.38 | 4.57 vs 3.38 | 4.09 vs 3.38 | 4.52 vs 3.38 | 4.80 vs 3.38 | 8.86 vs 7.38 |

| Φ24B | 5 | 8.90 vs 8.40 | 8.64 vs 8.30 | 8.81 vs 8.30 | 8.86 vs 8.30 | 8.83 vs 8.30 | 8.86 vs 8.30 | NI | 8.90 vs 8.40 |

Number of independent replicate experiments.

Those cases showing no consistent results in the replicate experiments are shown in italic type (in some cases, infection by the recombinant phage failed); results show the average of the most common effect. Those cases where more lysogens harboring two phages (Stx and incoming phage) were generated than lysogens in E. coli K-12 (harboring only the incoming phage) were generated are shown in bold type. PS, phage substitution, the incoming phage replaced the Stx prophage present in the Lys strain. NI, no infection (lysogens harboring two phages were not generated after several attempts).

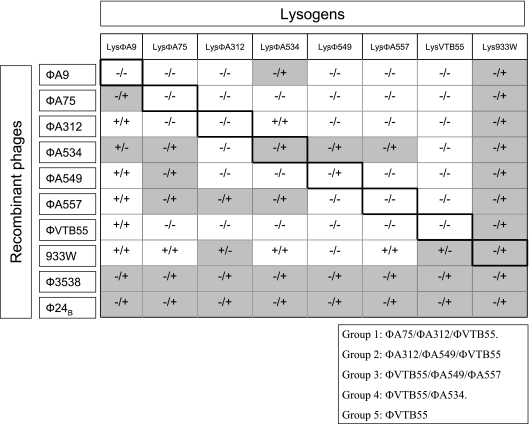

The immunity relationship among the 10 phages showed that only some of the phages were able to generate plaques on single-lysogen lawns, while others were only able to convert them (Fig. 3). The same results were observed for cat or tet recombinant phages. The group of phages studied appeared mostly heteroimmune, although some phages can be grouped according to their inability to infect other lysogens in a lytic or lysogenic way. Group 1 consisted of ΦA75, ΦA312, and ΦVTB55. Group 2 was made up of ΦA312, ΦA549, and ΦVTB55. Group 3 contained ΦA549, ΦA557, and ΦVTB55, and group 4 consisted of ΦA534 and ΦVTB55. Group 5 consisted of phage ΦVTB55, which can be considered a new group because it belongs to the first four groups (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Evaluation of the sensitivity of lytic versus lysogenic infection (lytic/lysogenic) of each recombinant phage on each E. coli lysogen. Results of lytic infection were obtained by spot test and hybridization with the specific probe. Results of lysogenic infection were obtained by colony blotting and confirmed by PCR. The sensitivity of lytic versus lysogenic infection (lytic/lysogenic) are shown as follows: for lytic infection, −, no lysis; +, lysis; for lysogenic infection, −, no lysogenic conversion in the lysogen or no substitution; +, lysogenic conversion with the recombinant phage. Those cases in which lytic infection was achieved but lysogenic infection was not or vice versa are indicated by gray shading. The different immunity groups (groups 1 to 5) established are shown at the bottom of the figure.

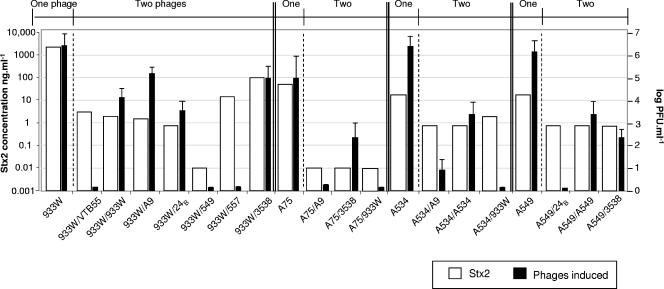

Determination of Shiga toxin production from lysogens harboring one or two Stx2 prophages.

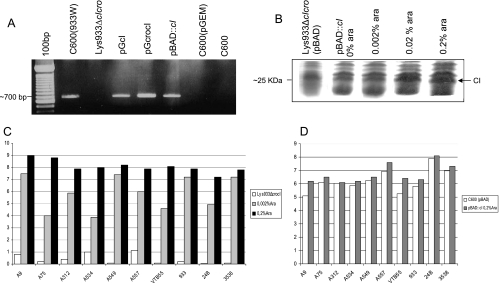

Shiga toxin generation was evaluated after the induction of the lytic cycle of the lysogens. Figure 4 shows representative cases in which the toxin produced from a strain carrying one Stx2 prophage is compared with the toxin produced from strains harboring two prophages. Lysogens with two prophages produced less toxin than those carrying only one prophage. The cytotoxicity assays done with the toxin produced by a lysogen carrying only one prophage showed stronger cytotoxicity than those performed with the toxin produced by the respective strains with two prophages (Table 4). Toxicity was normally observed after 24 to 48 h of incubation.

FIG. 4.

Comparison of toxin and phage production between lysogens carrying one Stx prophage and lysogens carrying two prophages (Stx2 phage and a recombinant phage). Phages are shown below the x axis without the initial Φ symbol. Toxin production was evaluated in the supernatant of the cultures after mitomycin C induction. The concentration was calculated with a standard curve performed with purified Stx2. Values on the z axis correspond to the phage counts on S. sonnei strain 866 in the supernatants of the cultures after mitomycin C induction. The results are the averages plus standard deviations (error bars) from three independent trials.

TABLE 4.

Cytotoxic effect on Vero cells and number of phage

| Lysogena | Cytotoxic effect (CD50·ml−1)b | Phage count (PFU ml−1)c |

|---|---|---|

| Lys(933W) | 1 × 105 | 4.9 × 106 |

| Lys(933W/ΦVTB55) | 5 × 101 | <101 |

| Lys(933W/933W) | 5 × 102 | 3.1 × 104 |

| Lys(933W/ΦA9) | 5 × 102 | 2.1 × 105 |

| Lys(933W/Φ24B) | 5 × 102 | 6.6 × 103 |

| Lys(933W/ΦA549) | 5 × 101 | <101 |

| Lys(933W/ΦA557) | 101 | <101 |

| Lys(933W/Φ3538) | 5 × 102 | 1.0 × 105 |

| Lys(ΦA75) | 102 | 1.4 × 105 |

| Lys(ΦA75/ΦA9) | 1 | 1.0 × 101 |

| Lys(ΦA75/Φ3538) | 1 | 5 × 102 |

| Lys(ΦA75/933W) | 1 | <101 |

| Lys(ΦA534) | 5 × 102 | 1.9 × 106 |

| Lys(ΦA534/ΦA9) | 1 | 1.0 × 101 |

| Lys(ΦA534/ΦA534) | 10 | 2.3 × 103 |

| Lys(ΦA534/933W) | 10 | <101 |

| Lys(ΦA549) | 1 × 104 | 1.2 × 106 |

| Lys(ΦA549/Φ24B) | 50 | <101 |

| Lys(ΦA549/ΦA549) | 10 | 2.0 × 103 |

| Lys(ΦA549/Φ3538) | 10 | 4.1 × 104 |

The lysogens harboring only one phage are shown in bold type.

Cytotoxic effect on Vero cells (CD50 ) of the supernatants of the induced cultures of lysogens carrying one or two prophages. Values of CD50 were measured on Vero cells and correspond to the dilution of the supernatant of the induced cultures that produces a 50% reduction of the cells.

Number of phage present in the supernatants of the induced lysogens detected on S. sonnei strain 866.

In these experiments, we detected only the Shiga toxin produced by the wild-type prophage, since the recombinant prophages cannot produce Stx, and consequently, no toxin was detected. The control assays performed confirmed that the commercial kit used did not detect the product of the truncated stx harbored by the recombinant phages.

To discard the possibility that the diminished expression observed was a transport problem from the cell, we used sonicated cultures of Lys933W, lysogens carrying the 10 recombinant phages, and the set of double lysogens containing both 933W and a recombinant phage. The supernatant of sonicated cultures showed the same results observed for the nonsonicated cultures (data not shown).

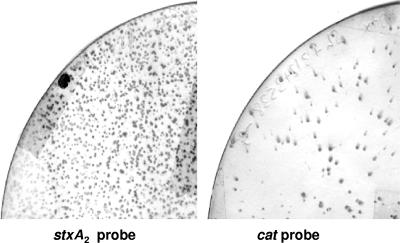

Besides the reduction in toxin production, strains with two prophages also produced fewer phage particles (Fig. 4 and Table 4). This was observed on the basis of the optical density measurements of the cultures and by plaque counts. Plaques enumerated by plaque blot hybridization using stx2 and the cat-, tet-, or aph-specific probes suggested that approximately 70% of the plaques corresponded to the Stx2 phage and the rest of the plaques corresponded to the recombinant phage (for example, see Fig. 5 with LysA549/3538).

FIG. 5.

Plaque assay of phages induced from strain LysA549/3538 carrying two phages. Most of the plaques generated from lysogenic strains harboring two prophages correspond to the Stx2 phage. Both membranes were transferred from the same plate in the same experiment; one was hybridized with the stxA2 probe, while the other was hybridized with the cat probe to reveal the differences in plaque formation of each phage present in the E. coli strain harboring both phages.

The order of infection of the two phages does not seem be relevant, since for example, similar results were obtained with strain Lys(24B/933W) and Lys(933W/24B). The results obtained in cytotoxicity (CD50, 5 × 102) and phage induction (3 × 103 PFU ml−1) were comparable with results obtained with Lys933W/24B presented in Table 4 and Fig. 4.

Some experiments performed with infection of two phages harboring antibiotic cassettes (cat or tet) were conducted to evaluate whether the number of phages produced upon induction vary if the order of conversion varied as well. These assays allowed only evaluation of phage production, without consideration to Stx, which can be produced only from a wild-type Stx2 prophage.

Lys534Cm/933Tc was compared to Lys933Tc/534Cm; after induction, they produced 9 PFU ml−1 versus 14 PFU ml−1. Lys3538/933Tc versus Lys933Tc/3538 produced 4 × 105 versus 2.6 × 105 PFU ml−1, respectively, and Lys549Cm/549Tc versus Lys549Tc/549Cm produced 1.4 × 103 versus 2.3 × 103 PFU ml−1, respectively (results are representative of three independent replicate experiments). Although some variations can be observed, the results do not show consistent differences that can lead to strong conclusions. The main differences are observed in comparisons of the double lysogens with the single lysogens, with less phage produced by the double lysogens than by the single lysogens, as previously reported (Fig. 4 and Table 4).

Implied role of cI and cro in the incorporation of a second prophage.

The lysogen carrying the 933W Stx2 prophage was selected for these studies because it was the only lysogen that allowed lysogenic infection with all the other phages and no cases of phage substitution or noninfection were observed (Table 3). A cro mutant (Lys933WΔcro::cat) was obtained by the incorporation of a cat gene using the Red recombinase system (Fig. 2) and used as host for infection with Δstx::tet phages.

After several attempts, a stable mutant with only the cI gene knocked out was not obtained, probably because the lack of cI regulator implies a constitutive activation of the lytic cycle and a loss of 933W prophage (39). Nevertheless, a stable mutant lacking the fragment between the cI and cro genes was successfully generated (Lys933WΔcIΔcro) and used as host for infection with the Δstx::cat phages.

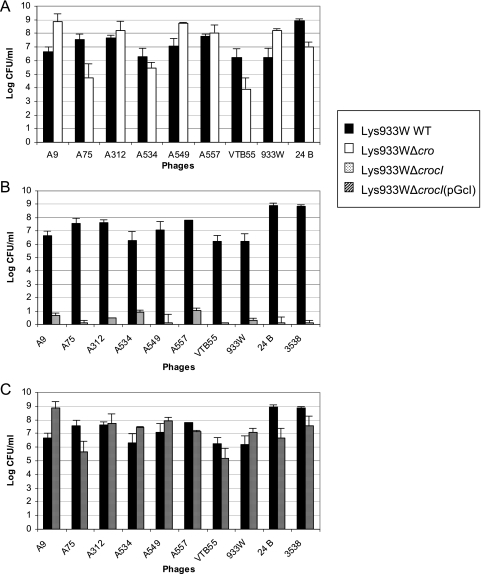

The lack of expression of cI and/or cro in the mutant strains was confirmed by RNA extraction of the strains, followed by RT-PCR. In contrast, positive RT-PCR amplification was achieved with RNA from the strains harboring pGcI, pGcIcro, and pGcro, confirming that all constructs expressed cI (see Fig. 7A) or cro. Strains C600 and C600(pGEM) were used as negative controls, while C600(933W) was the positive control.

FIG. 7.

Effect of cI expression in the incorporation of a second prophage. (A) Expression of cI in the constructs evaluated by RT-PCR. (B) Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis showing CI protein produced by the Lys933WΔcroΔcI mutant complemented with pBAD::cI in the absence of arabinose or at different final concentrations of arabinose (Ara). The mutant strain harboring pBAD vector without an insert at 0.2% arabinose was the control. (C) Representative experiment showing generation of colonies incorporating a second prophage in the Lys933WΔcIΔcro mutant harboring empty pBAD (with 0.2% arabinose) and pBAD::cI induced with 0.002 or 0.2% arabinose. (D) Representative experiment showing strain C600 harboring pBAD and pBAD::cI, expression induced with 0.2% arabinose. In panels C and D, phages are shown below the x axes without the initial Φ symbol and log CFU/ml is shown on the y axes.

There was no significant difference between the Lys933WΔcro mutant and the wild-type C600(933W) in the number of colonies incorporating a second prophage (Fig. 6A). The C600 control did not show differences either. Complementation with pGEMcro did not affect the generation of double lysogens.

FIG. 6.

Effects of lysogen (933W) cI and cro genes in the incorporation of a second prophage. (A) Generation of colonies incorporating a second prophage in the wild-type (WT) Lys933W strain compared with the Lys933WΔcro mutant. (B) Same as panel A but comparing the wild-type Lys933W strain with the Lys933WΔcIΔcro mutant. (C) Same as panel B after complementation of the Lys933WΔcIΔcro mutant with plasmid pGcI. Phages are shown below the x axis without the initial Φ symbol. Results are the averages plus standard deviations (error bars) from three independent experiments.

In contrast, Lys933WΔcIΔcro generated fewer colonies acquiring a second prophage than the wild type did (Fig. 6B). Phage generation was checked in these cultures (without induction), and the number of phages present in the supernatant of these cultures was low (below 102 PFU·ml−1), indicating that spontaneous phage induction was not the cause of the low number of double lysogens generated with the mutant.

When the mutated strain was complemented with pGcI, the difference with the wild type was removed (Fig. 6C). Negative controls with empty vectors (pGEM) were examined and did not show relevant differences compared with the noncomplemented mutant. Strain C600 alone or complemented with pGcI was also used as a control for a prophage-free strain, and although not significant, a small increase in the number of colonies which incorporated a new prophage was observed in those carrying pGcI (data not shown).

The pBAD::cI construct was used to evaluate the influence of CI concentration in the generation of lysogens with two phages. RT-PCR confirmed cI expression in the strains harboring this construct (Fig. 7A). pBAD::cI showed a higher level of expression of cI at a final arabinose concentration of 0.2% in Lys933WΔcIcro (Fig. 7B). Similar results were observed for control strains LMG194 and C600 (data not shown). Complementation of the mutant strain with pBAD::cI when the highest cI expression was activated (0.2% arabinose) led to the generation of more lysogens carrying the second phage than with lower cI concentrations (0.002% arabinose) (Fig. 7C). Strain C600 with the pBAD::cI construct induced with 0.2% arabinose showed a higher rate of incorporation of the prophage than the naïve strain did, although the difference between both sets of experiments were not as relevant as observed with the mutant (Fig. 7D). These results indicate that cI seems to be involved in the incorporation of the second prophage. However, some other factors present in the 933WΔcIΔcro prophage should hinder the incorporation of the second prophage in the mutant strain, since incorporation of a single phage in strain C600 with or without pBAD::cI can be easily achieved.

Negative controls with empty vectors (pBAD) were used and did not show relevant differences compared with the noncomplemented mutant.

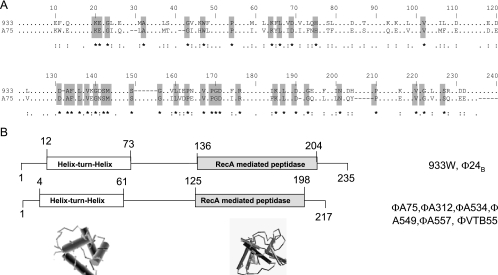

Assuming that the cI product plays a role in the integration of a second prophage in the 933W lysogen chromosome, 933W CI protein could interact with the second prophage, producing a more stable lysogenic state and causing a reduction in toxin production at the same time. We evaluated the differences in the sequences of the cI genes of the 10 phages studied, and the amino acid sequences of the proteins encoded by the genes were compared. The cI genes of all phages, except for phage ΦA9 and Φ3538, were sequenced successfully. For the phages studied, there were differences in the amino acid sequences of the CI proteins (Fig. 8). To evaluate the relevance of the differences in the protein structure, the CI protein conformation was analyzed to examine whether cI genes of heteroimmune phages could work in trans. All CI proteins analyzed shared two common domains (Fig. 8). The first domain corresponds to a helix-turn-helix domain in the NH2-terminal half of CI that mediates its DNA binding. The second domain corresponds to a RecA-mediated peptidase that enhances CI self-cleavage after RecA binding, breaking the CI homodimer, so that the repressor can no longer form dimers and bind DNA.

FIG. 8.

(A) Alignment of the CI protein sequences of the phages studied, 933W (933) and ΦA75 (A75). The proteins were aligned using CLUSTALW (http://npsa-pbil.ibcp.fr/cgi-bin/npsa_automat.pl?page=/NPSA/npsa_clustalw.html). Amino acids that were identical in the two phages are indicated by asterisks and gray shading. Symbols in the sequence: −, no amino acids in this fragment in one of the sequences; ., the amino acids of both sequences are noncoincident. Symbols below the sequence: :, amino acids of both chains are strongly similar; ., amino acids of both chains are weakly similar. (B) Domain map of CI. The protein domains are indicated. The white boxes represent the helix-turn-helix XRE region for DNA binding. The gray boxes represent the RecA-mediated peptidase domains which correspond to the self-cleavage of CI mediated by RecA activity. The predicted model for each domain is indicated below the boxes.

DISCUSSION

Shiga toxins are major virulence factors in STEC. They are encoded in the genomes of temperate lambdoid phages (19), and Stx expression is normally linked to induction of the lytic cycle (43), which allows the release of toxin. A large proportion of the STEC strains isolated from the environment usually carry more than one Stx prophage (2, 3, 17, 24, 34, 50, 54). The presence of more than one stx copy in the host chromosome can alter the expression and release of Shiga toxin. It has been reported that isolates of STEC with two copies of an stx gene produced significantly more Stx in vitro than did strains of the same serotype containing a single copy of the same stx gene (3, 11). In contrast, some evidence of Stx competition has been identified in wild-type pathogenic E. coli O157:H7 (9), and it has also been suggested that the presence of two phages can reduce the Stx produced and that the loss of one of the prophages consequently produced a significant increase in Stx production (34). In order to study this effect, we generated E. coli K-12 strains carrying either one or two Stx2 prophages. We used Shiga toxin-encoding bacteriophages that appeared to be heterogeneous in their host infectivity, phage genome size, insertion site occupancy when converting different host strains, stx2 gene sequence, restriction fragment length polymorphism, and integrase sequence (13, 33, 46). In the present study, we also examined their immunity profiles: most of them appeared heteroimmune, although four immunity groups can be established.

Our finding that incorporation of a second prophage generated more lysogens could be explained as follows: transduction generates lysogens harboring two phages. Once produced, these lysogens show lower phage induction rates than lysogens carrying only one phage, which reduces the number of lysed colonies, thus allowing the growth of these lysogens once generated. The relatively easy generation of strains harboring two prophages could explain the abundance of STEC strains carrying more than one Stx prophage. Similar observations have already been made in other studies, where lysogens seemed to be good hosts for new prophages (13, 15, 23, 31).

Heteroimmune curing or substitution of one phage by the incoming one was also a frequent event observed in our studies and can be explained by natural immunity between the two phages. Superinfection of a lysogen by a phage with a different immunity but the same recombinase frequently leads to the loss of the original prophage (heteroimmune curing) (48). No infection by the second prophage or more colonies harboring only one prophage were observed in only a few cases.

In those cases in which we obtained lysogens carrying two Stx2 prophages, toxin production decreased as a result of lower phage production after the lytic cycle was induced. This observation suggests gene regulation between both phages and confirms the direct link between phage induction and toxin production (43). In consequence, the lysogenic state seems to be stabilized by the presence of a second prophage. This finding is consistent with our observations of certain lysogens carrying one Stx prophage (for example, LysΦA75), in which spontaneous induction (28) of the lytic cycle was observed. In these lysogens, spontaneous induction was not longer detected when a second prophage was incorporated (data not shown).

Moreover, our results are consistent with previous studies in which wild O157:H7 STEC strains isolated from the same outbreak could harbor either one or two functional Stx2 phages (34). In that study, toxin production was also evaluated, indicating that less toxin was generated when two prophages coexisted in the same cell. This indicates that toxin production depends on the lytic cycle induction rate (which is linked to phage production and toxin release) rather than on the number of functional stx2 genes present in the bacterial chromosome. The finding that our E. coli lysogens carrying two prophages produce fewer infectious viral particles indicates that these strains are less susceptible to the SOS response to activate their lytic cycle, thus producing less toxin. Despite the fact that our results are in accordance with previous observations, it should be noted that the experiments presented here have been performed with phages isolated mostly from animal strains, and thus, our results might differ from experiments with human isolates (3, 11). In addition, our data were obtained in an E. coli K-12 background under experimental conditions that differ from the physiological situation (16); therefore, they cannot be necessarily transferred into an in vivo situation during natural human STEC infection.

Experiments conducted to determine which genes could be involved in the acquisition of a second prophage in a 933W lysogen that lowers toxin production indicate that the cI repressor of the 933W phage is involved. The mutant strain constructed lacks the whole fragment between the cI and cro genes, including promoters pRM and pR. Deletion of the whole fragment including the promoters avoids interference with the incoming phage, although the mutated prophage is not inducible anymore. With the exception of N, all phage-encoded functions required for lytic growth ultimately derive from transcription initiation at pR (52, 53). By deleting pR, we blocked the expression of cII, but this was not relevant, since CII directly affects cI, which was truncated. CII can also act on int, but since the phage was already integrated, this should not be a problem, and in addition we avoid excision, a process in which int is also involved together with xis. The lack of excision was experimentally confirmed. The pRE promoter, however, involved in the lytic-lysogenic pathway decision at early stages remained intact. Results of complementation with pGcI suggested that even cI or pR should be involved in generation of double lysogens. Results of complementation with pBAD::cI clearly suggested that cI plays a role in the generation of double lysogeny and suggested that different concentrations of the repressor influence the incorporation of the incoming phage differently. Our results indicate, however, that some other genes present in the mutated prophage must also be involved in blocking infection with the second incoming phage, since the mutant strain (harboring the mutated prophage) generates a low number of double lysogens, while a high number of lysogens are produced when the incoming phage infects a naïve C600 strain (prophage-free) or C600(pBAD::cI). Nevertheless, the unknown gene must somehow be linked to cI, which is involved in a direct or indirect way in the incorporation of the incoming phage in the nonmutated strains.

We hypothesize that the lytic repressor of different phages can act in trans and regulate the lysogenic cycle of the two phages present in the same genome. For those cases in which they appeared heteroimmune and the cI sequences were unrelated, we observed conserved CI protein domains that might enhance binding to the operator regions of the second prophage, stabilizing the lysogenic state and reducing toxin production. This conclusion cannot be extrapolated to phages ΦA9 and Φ3538, since successive attempts to identify and sequence their cI gene were unsuccessful. For those phages sharing identical cI and operator regions, such as phage 933W or phage Φ24B (13, 38), or for phages of this study which shared the same regulator sequences, the explanation is not so clear. The possible presence of an antirepressor has been suggested as a mechanism to allow superinfection of phage Φ24B (13) by cleavage of the CI protein. This would reduce the concentration of CI, avoiding immunity due to repression by CI protein. However, the ant gene was not identified in our phages (data not shown) or in 933W, although the presence of another gene encoding a protein with the same antirepressor role cannot be excluded. In experiments with the Lys933W mutant, our results suggest that since the CI protein of the 933W prophage cannot be produced, the CI concentration of the second phage alone is not sufficient to enhance its incorporation. The amounts of CI or CI homologues caused by the synergic presence of two cI genes or their reduction by the action of a possible antirepressor could explain the variations observed within our group of prophages. Our experiments also suggest differences in the incorporation of the second phage depending on the CI concentration, but more accurate experiments would be necessary to identify the threshold concentration of CI and/or CI homologues necessary to decide whether the incoming phage will integrate or whether superinfection will occur. These observations are in agreement with other authors who anticipate that 933W prophages would direct the synthesis of a tightly regulated amount of repressor (26). They are also consistent with other authors who suggest that repressor differences may be responsible for the variations in toxin and phage production observed in different lysogens obtained with the same host strain (55). Wagner et al. (55) also suggest that with more than one prophage repression system present in a host strain, the control of Stx2 production may move further away from the lytic switch of the prophage and more toward a matrix of interaction between phage repressors and host factors, as confirmed in our work. Moreover, since several truncated prophages without the stx gene have been identified in wild-type pathogenic E. coli O157:H7 (29), the repressor genes present in these prophages could theoretically influence the expression of other phages (including other Stx prophages) present in the same chromosome, controlling their induction and expression of the genes encoded by these phages, including the stx gene among other genes.

The acquisition of more genetic information by the incorporation of a prophage can provide the cell with new functions. For instance, pathogenic genes, which under certain conditions could be beneficial to bacteria, are also a survival strategy for phages (6, 8, 18). Generally, without any selection, temperate phages are spontaneously induced and subsequently lost. This explains why most STEC strains do not possess two phages in their genome. However, in some cases, the presence of more than one prophage facilitates their maintenance in the bacterial chromosome. The explanation of evolutionary advantage suggested for a single phage can also be applied to a second phage. The contribution of phages (together with plasmids, transposons, or pathogenicity islands) to the evolution of bacteria is widely recognized, as they behave as vectors for gene acquisition (8, 12, 18, 47, 55). In this context, phages contribute to short-term bacterial diversification (8). Nevertheless, bacteria need to acquire and fix these genes to achieve long-term genetic diversification (8, 27). The reduction of lytic induction observed in our lysogens carrying two prophages could be considered a first step toward the stabilization of genetic information in the host strains. This could be regarded a prerequisite to fix the new genes. The reduction of lytic induction implies a reduction in toxin production, which produces a less virulent strain. This seems to be a logical strategy to colonize a new environment effectively. A fraction of the population would be able to activate its lytic cycle, causing the destruction of this fraction, but allowing the whole population to be virulent. Another fraction would keep its lysogenic state stable, which reduces the pathogenicity of this fraction, but ensures the maintenance of the population.

Acknowledgments

We thank H. Schmidt for providing strain C600(Φ3538), H. E. Allison for providing strain MC1061(Φ24B), and E. Freire for excellent technical assistance.

This study was supported by the Generalitat de Catalunya (2005SGR00592) and by the Spanish Ministry of Education and Science (AGL200601566/ALI). R. Serra is a recipient of a grant from the Spanish Ministry of Education and Science (AP2003-3971).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 9 May 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Acheson, D. W. K., J. Reidl, X. Zahang, G. T. Keusch, J. J. Mekelanos, and M. K. Waldor. 1998. In vivo transduction with Shiga toxin 1-encoding phage. Infect. Immun. 664496-4498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allison, H. E., M. J. Sergeant, C. E. James, J. R. Saunders, D. L. Smith, R. J. Sharp, T. S. Marks, and A. J. McCarthy. 2003. Immunity profiles of wild-type and recombinant Shiga-like toxin-encoding bacteriophages and characterization of novel double lysogens. Infect. Immun. 713409-3418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bielaszewska, M., R. Prager, W. Zhang, A. W. Friedrich, A. Mellmann, H. Tschape, and H. Karch. 2006. Chromosomal dynamism in progeny of outbreak-related sorbitol-fermenting enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:NM. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 721900-1919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bielaszewska, M., W. Zhang, A. Mellmann, and H. Karch. 2007. Enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli O26:H11/H-: a human pathogen in emergence. Berl. Munch. Tierarztl. Wochenschr. 120279-287. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blanco, J., M. Blanco, J. E. Blanco, A. Mora, M. P. Alonso, E. A. González, and M. I. Bernárdez. 2001. Epidemiology of verocytotoxigenic Escherichia coli (VTEC) in ruminants, p. 113-148. In G. Duffy, P. Garvey, and D. McDowell (ed.), Verocytotoxigenic Escherichia coli. Food & Nutrition Press Inc., Trumbull, CT.

- 6.Brüssow, H., C. Canchaya, and W. D. Hardt. 2004. Phages and the evolution of bacterial pathogens: from genomic rearrangements to lysogenic conversion. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 68560-602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Campbell, A. 1994. Comparative molecular biology of lambdoid phages. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 48193-222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Canchaya, C., G. Fournous, and H. Brussow. 2004. The impact of prophages on bacterial chromosomes. Mol. Microbiol. 539-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cornick, N. A., S. Jelacic, M. A. Ciol, and P. I. Tarr. 2002. Escherichia coli O157:H7 infections: discordance between filterable fecal Shiga toxin and disease outcome. J. Infect. Dis. 18657-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Datsenko, K. A., and B. L. Wanner. 2000. One step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 976640-6645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eklund, M., K. Leino, and A. Siitonen. 2002. Clinical Escherichia coli strains carrying stx genes: stx variants and stx-positive virulence profiles. J. Clin. Microbiol. 404585-4593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Escobar-Paramo, P., O. Clermont, A. B. Blanc-Potard, H. Bui, C. Le Bouguenec, and E. Denamur. 2004. A specific genetic background is required for acquisition and expression of virulence factors in Escherichia coli. Mol. Biol. Evol. 211085-1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fogg, P. C., S. M. Gossage, D. L. Smith, J. R. Saunders, A. J. McCarthy, and H. E. Allison. 2007. Identification of multiple integration sites for Stx-phage Φ24B in the Escherichia coli genome, description of a novel integrase and evidence for a functional anti-repressor. Microbiology 1534098-4110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fraser, M. E., M. Fujinaga, M. M. Cherney, A. R. Melton-Celsea, E. M. Twiddy, A. D. O'Brien, and M. N. G. Jamens. 2004. Structure of Shiga toxin type 2 from Escherichia coli O157:H7. J. Biol. Chem. 27927511-27517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Furst, S., J. Scheef, M. Bielaszewska, H. Russmann, H. Schmidt, and H. Karch. 2000. Identification and characterisation of Escherichia coli strains of O157 and non-O157 serogroups containing three distinct Shiga toxin genes. J. Med. Microbiol. 49383-386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gamage, S. D., A. K. Patton, J. F. Hanson, and A. A. Weiss. 2004. Diversity and host range of Shiga toxin-encoding phage. Infect. Immun. 727131-7139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Garcia-Aljaro, C., M. Muniesa, J. E. Blanco, M. Blanco, J. Blanco, J. Jofre, and A. R. Blanch. 2005. Characterization of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli isolated from aquatic environments. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 24655-65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hendrix, R. W. 2002. Bacteriophages: evolution of the majority. Theor. Popul. Biol. 61471-480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Herold, S., K. Karch, and H. Schmidt. 2004. Shiga-toxin-converting bacteriophages. Genomes in motion. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 294115-121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Herold, S., J. Siebert, A. Huber, and H. Schmidt. 2005. Global expression of prophage genes in Escherichia coli O157:H7 strain EDL933 in response to norfloxacin. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49931-944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hoey, D. E., C. Currie, R. W. Else, A. Nutikka, C. A. Lingwood, D. L. Gally, and D. G. Smith. 2002. Expression of receptors for verotoxin 1 from Escherichia coli O157 on bovine intestinal epithelium. J. Med. Microbiol. 51143-149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jaeger, J. L., and D. W. Acheson. 2000. Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli. Curr. Infect. Dis. Rep. 261-67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jiang, S. C., and J. H. Paul. 1998. Gene transfer by transduction in the marine environment. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 642780-2787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Johansen, B. K., Y. Wasteson, P. E. Granum, and S. Brynestas. 2001. Mosaic structure of Shiga-toxin-2 encoding phages isolated from Escherichia coli O157:H7 indicates frequent gene exchange between lambdoid phage genomes. Microbiology 1471929-1936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kaper, J. B., J. P. Nataro, and H. L. Mobley. 2004. Pathogenic Escherichia coli. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2123-140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Koudelka, A. P., L. A. Hufnagel, and G. B. Koudelka. 2004. Purification and characterization of the repressor of the Shiga toxin-encoding bacteriophage 933W: DNA binding, gene regulation, and autocleavage. J. Bacteriol. 1867659-7669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lawrence, J. G., and J. R. Roth. 1999. Genomic flux: genomic evolution by gene loss and acquisition, p. 263-289. In R. L. Charleboir (ed.), Organization of the prokaryotic genome. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC.

- 28.Livny, J., and D. I. Friedman. 2004. Characterizing spontaneous induction of Stx encoding phages using a selectable reporter system. Mol. Microbiol. 511691-1704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Makino, K., K. Yokoyama, Y. Kubota, C. H. Yutsudo, S. Kimura, K. Kurokawa, K. Ishii, M. Hattori, I. Tatsuno, H. Abe, T. Iida, K. Yamamoto, M. Onishi, T. Hayashi, T. Yasunaga, T. Honda, C. Sasakawa, and H. Shinagawa. 1999. Complete nucleotide sequence of the prophage VT2-Sakai carrying the verotoxin 2 genes of the enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7 derived from the Sakai outbreak. Genes Genet. Syst. 74227-239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marques, L. R. M., M. A. Moore, J. G. Wells, I. K. Wachsmuth, and A. D. O'Brien. 1986. Production of Shiga-like toxin by Escherichia coli. J. Infect. Dis. 154338-341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miller, R. V., S. Ripp, J. Replicon, O. Ogunseitan, and T. A. Kokjohn. 1992. Virus-mediated gene transfer in freshwater environments, p. 50-62. In M. J. Gauthier (ed.), Gene transfers and environment. Springer-Verlag, Berlin, Germany.

- 32.Muniesa, M., and J. Jofre. 1998. Abundance in sewage of bacteriophages that infect Escherichia coli O157:H7 and that carry the Shiga toxin 2 gene. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 642443-2448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Muniesa, M., J. E. Blanco, M. De Simon, R. Serra-Moreno, A. R. Blanch, and J. Jofre. 2004. Diversity of stx2 converting bacteriophages induced from Shiga-toxin-producing Escherichia coli strains isolated from cattle. Microbiology 1502959-2971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Muniesa, M., M. de Simon, G. Prats, D. Ferrer, H. Panella, and J. Jofre. 2003. Shiga toxin 2-converting bacteriophages associated with clonal variability in Escherichia coli O157:H7 strains of human origin isolated from a single outbreak. Infect. Immun. 714554-4562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nataro, J. P., and J. B. Kaper. 1998. Diarrhoeagenic Escherichia coli. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 11142-201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.O'Brien, A. D., J. W. Newland, S. F. Miller, R. K. Holmes, H. W. Smith, and S. B. Formal. 1984. Shiga-like toxin-converting phages from Escherichia coli strains that cause hemorrhagic colitis or infantile diarrhea. Science 226694-696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Paton, J. C., and A. W. Paton. 1998. Pathogenesis and diagnosis of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli infections. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 11450-479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Plunkett, G., J. D. Rose, T. J. Durfee, and F. R. Blattner. 1999. Sequence of Shiga toxin 2 phage 933W from Escherichia coli O157:H7: Shiga toxin as a phage late-gene product. J. Bacteriol. 1811767-1778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rokney, A., O. Kobiler, A. Amir, D. L. Court, J. Stavans, S. Adhya, and A. B. Oppenheim. 2008. Host responses influence on the induction of lambda prophage. Mol. Microbiol. 6829-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rose, R. E. 1988. The nucleotide sequence of pACYC184. Nucleic Acids Res. 16355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Russmann, H., H. Schmidt, A. Caprioli, and H. Karch. 1994. Highly conserved B-subunit genes of Shiga-like toxin II variants found in Escherichia coli O157 strains. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 118335-340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sambrook, J., and D. W. Russell. 2001. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 3rd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 43.Schmidt, H. 2001. Shiga toxin converting bacteriophages. Res. Microbiol. 152687-695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schmidt, H., M. Bielaszewska, and H. Karch. 1999. Transduction of enteric Escherichia coli isolates with a derivative of Shiga toxin 2-encoding bacteriophage φ3538 isolated from E. coli O157:H7. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 653855-3861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Serra-Moreno, R., S. Acosta, J.-P. Hernalsteens, J. Jofre, and M. Muniesa. 2006. Use of the lambda Red recombinase system to produce recombinant prophages carrying antibiotic resistance genes. BMC Mol. Biol. 731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Serra-Moreno, R., J. Jofre, and M. Muniesa. 2007. Insertion site occupancy by stx2 bacteriophages depends on the locus availability of the host strain chromosome. J. Bacteriol. 1896645-6654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Silander, O. K., D. M. Weinreich, K. M. Wright, K. J. O'Keefe, C. U. Rang, P. E. Turner, and L. Chao. 2005. Widespread genetic exchange among terrestrial bacteriophages. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 10219009-19014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Six, E. 1960. Prophage substitution and curing in lysogenic cells superinfected with hetero-immune phage. J. Bacteriol. 80728-729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tarr, P. I., C. A. Gordon, and W. L. Chandler. 2005. Shiga-toxin-producing Escherichia coli and hemolytic uraemic syndrome. Lancet 3651073-1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Teel, L. D., A. R. Melton-Celsa, C. K. Schmitt, and A. D. O'Brien. 2002. One of two copies of the gene for the activable Shiga toxin type 2d in Escherichia coli O91:H21 strain B2F1 is associated with an inducible bacteriophage. Infect. Immun. 704282-4291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tóth, I., H. Schmidt, M. Dow, A. Malik, E. Oswald, and B. Nagy. 2003. Transduction of porcine enteropathogenic Escherichia coli with a derivative of a Shiga toxin 2-encoding bacteriophage in a porcine ligated ileal loop system. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 697242-7247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tyler, J. S., J. Livny, and D. I. Friedman. 2005. Lambdoid phages and Shiga toxin, p. 131-164. In M. K. Waldor, D. I. Friedman, and S. L. Adhya (ed.), Phages: their role in bacterial pathogenesis and biotechnology. ASM Press, Washington DC.

- 53.Tyler, J. S., M. J. Mills, and D. I. Friedman. 2004. The operator and early promoter region of the Shiga toxin type 2-encoding bacteriophage 933W and control of toxin expression. J. Bacteriol. 1867670-7679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Unkmeir, A., and H. Schmidt. 2000. Structural analysis of phage-borne stx genes and their flanking sequences in Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli and Shigella dysenteriae type 1 strains. Infect. Immun. 684856-4864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wagner, P. L., D. W Acheson, and M. K. Waldor. 1999. Isogenic lysogens of diverse Shiga toxin 2-encoding bacteriophages produce markedly different amounts of Shiga toxin. Infect. Immun. 676710-6714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Weinstein, D. L., M. P. Jackson, L. J. Perera, R. K. Holmes, and A. D. O'Brien. 1989. In vivo formation of hybrid toxins comprising Shiga toxin and the Shiga-like toxins and role of the B subunit in localization and cytotoxic activity. Infect. Immun. 573743-3750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Woodcock, D. M., P. J. Crowther, J. Doherty, S. Jefferson, E. DeCruz, M. Noyer-Weidner, S. S. Smith, M. Z. Michael, and M. W. Graham. 1989. Quantitative evaluation of Escherichia coli host strains for tolerance to cytosine methylation in plasmid and phage recombinants. Nucleic Acids Res. 173469-3478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]