Abstract

Vibrio fischeri quorum sensing involves the LuxI and LuxR proteins. The LuxI protein generates the quorum-sensing signal N-3-oxohexanoyl-l-homoserine lactone (3OC6-HSL), and LuxR is a signal-responsive transcriptional regulator which activates the luminescence (lux) genes and 17 other V. fischeri genes. For activation of the lux genes, LuxR binds to a 20-base-pair inverted repeat, the lux box, which is centered 42.5 base pairs upstream of the transcriptional start of the lux operon. Similar lux box-like elements have been identified in only a few of the LuxR-activated V. fischeri promoters. To better understand the DNA sequence elements required for LuxR binding and to identify binding sites in LuxR-regulated promoters other than the lux operon promoter, we have systematically mutagenized the lux box and evaluated the activity of many mutants. By doing so, we have identified nucleotides that are critical for promoter activity. Interestingly, certain lux box mutations allow a 3OC6-HSL-independent LuxR activation of the lux operon promoter. We have used the results of the mutational analysis to create a consensus lux box, and we have used this consensus sequence to identify LuxR binding sites in 3OC6-HSL-activated genes for which lux boxes could not be identified previously.

Quorum sensing and response in bacteria involves the production and detection of diffusible signal molecules. Many species of Proteobacteria use acyl-homoserine lactones (acyl-HSL) as quorum-sensing signals (2, 10-13, 22, 28). Acyl-HSL quorum sensing was first described for the marine luminescent bacterium Vibrio fischeri, where the seven-gene luminescence (lux) operon is activated by a transcription factor called LuxR when it is bound by the quorum-sensing signal N-3-oxohexanoyl-l-HSL (3OC6-HSL) (6, 8, 9, 25). The 3OC6-HSL synthase is LuxI (20). The activation of the lux operon involves LuxR binding to a 20-base-pair inverted repeat centered at −42.5 from the transcriptional start site of the lux operon (5, 7, 25). LuxR is an ambidextrous activator that requires contact with the carboxy-terminal domain of the RNA polymerase α subunit and region 4 of the σ70 subunit (7, 16, 23).

For other bacteria, LuxR homologs often bind to promoter elements with sequence similarity to the lux box (12). The Agrobacterium tumefaciens TraR protein has been studied in considerable detail. A TraR crystal structure has been solved (29), and the lux box-like element to which TraR binds has been subjected to extensive mutational analysis (27). The binding of TraR to target DNA and subsequent activation of transcription involves many bases in the binding site. Some bases are involved in direct contact with TraR, some with the ability of TraR to bend DNA, and some with the ability of RNA polymerase to bind to the promoter (27). For LuxR, the available evidence indicates that the two distal bases of the lux box are not critical, but little else is known about lux box sequence requirements for LuxR binding and transcriptional activation (5).

We recently performed a transcriptome analysis and identified 10 promoters in addition to the promoter of the lux operon that are activated by LuxR directly (1). Of these 10, only 1 had an identifiable lux box. To begin to understand elements in LuxR binding sites that are required for LuxR-DNA interactions and to develop an understanding of how LuxR might bind to quorum-controlled promoters for which a lux box cannot be identified, we performed a mutational analysis of the lux box in the promoter of the lux operon. This analysis has enabled us to redefine a minimal lux box. By using the minimal lux box-like sequence, we have identified LuxR binding sites for 3OC6-HSL-activated genes other than those in the lux operon.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids and growth conditions.

We used Escherichia coli DH12S (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) cells for cloning and for analysis of mutant lux box activities. Vibrio fischeri ES114 (4) was used as the source of DNA for amplification of the lux operon promoter. Escherichia coli cells were grown in Luria-Bertani broth (19) without added sodium chloride at 30°C with shaking, and V. fischeri cells were grown at 28°C in L-marine medium (3) with shaking. Plating was on media with 2% agar. Chloramphenicol and kanamycin were used for plasmid maintenance at 25 and 50 μg/ml, respectively. Where indicated, we used 3OC6-HSL (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO) at a final concentration of 2.3 μM. The 3OC6-HSL was prepared as a concentrated stock in acidified ethyl acetate (100 μl of glacial acetic acid per liter). The stock was added to culture vessels, the ethyl acetate was removed by evaporation under a light stream of nitrogen, and then the culture medium was added.

The luxR expression vector used in our experiments was pHV402, which contains luxR under the control of its own promoter and contains a chloramphenicol resistance marker (14). We constructed our lux box mutant vectors in pPROBE-gfp[LVA]. This vector contains a promoterless short-half-life gfp and a kanamycin resistance marker (17).

DNA manipulations.

For purification of chromosomal DNA, PCR products, and plasmids, we used Qiagen kits (Germantown, MD) according to the manufacturer's procedures. For PCR amplifications, we used an Expand Long Template system (Roche, Indianapolis, IN). We obtained T4 polynucleotide kinase, T4 DNA ligase, and EcoRI from New England Biolabs (Ipswich, MA), and BamHI was obtained from Roche. All primers were synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA), and primer sequences are available upon request.

Site-directed mutagenesis and construction of transcriptional fusions.

We used site-directed mutagenesis to introduce nucleotide substitutions in the lux box of a native V. fischeri lux operon promoter. Briefly, we used primers containing restriction enzyme sites on their 5′ extremities in conjunction with primers that were completely or partially complementary to the lux box sequence to amplify the luxI promoter. Appropriate primers were used to amplify the upstream and downstream flanks of the promoter. The two flanks were purified and used as templates in a crossover reaction using the external primers. The final PCR products were digested with EcoRI and BamHI and ligated to similarly digested pPROBE-gfp[LVA] by using standard techniques (19). The restriction sites for EcoRI and BamHI are located in a multicloning site upstream of a promoterless gfp. Promoters cloned into EcoRI and BamHI-digested pPROBE-gfp[LVA] will function to initiate gfp transcription. The resulting plasmids were then used to transform E. coli cells in the presence or absence of the luxR expression vector pHV402 by electroporation, as previously described (19). To construct transcriptional fusions containing promoters of non-lux genes, a similar method was used. However, amplification of the promoter regions was performed as a single step since no internal primers were used and no nucleotide substitutions were introduced.

DNA sequencing and sequence analysis.

The lux promoters were PCR amplified and sequenced at either the University of Iowa DNA Facility or the University of Washington DNA Sequencing and Gene Analysis Center. Sequenced promoters were compared to the wild-type lux promoter sequence by using ClustalW (http://clustalw.genome.jp) (24). All plasmids used in this study possessed lux operon promoters that were identical to the wild-type promoter with the exception of the base substitutions introduced.

Analysis of promoter activity in recombinant E. coli cells.

Plasmids containing transcriptional fusions were introduced into E. coli cells in the presence or absence of the luxR expression vector pHV402, as indicated in the figure legends. Overnight cultures of the recombinant E. coli cells were used to inoculate fresh cultures with or without 3OC6-HSL, as indicated, at a starting optical density (600 nm) of 0.1. When the optical density reached 1.2 ± 0.2 (mean ± standard deviation), fluorescence was measured with a GENios Pro 96-well plate reader (TECAN, Research Triangle Park, NC). We chose an optical density which corresponds to late-logarithmic or early stationary growth because the differential in fluorescence between active and inactive promoters was at a maximum at this point. We used a fusion of the wild-type promoter to gfp as a positive control and the promoterless gfp plasmid pPROBE-gfp[LVA] as a negative control. The results are the averages of the results of three independent experiments, and the bars in the figures show the range of values obtained.

DNA mobility shift assays.

Gel-shift experiments were performed as previously described (25). Specific probes were generated by PCR amplification of promoter regions using the transcriptional fusion plasmids as templates. The nonspecific probe was obtained by PCR amplification of non-V. fischeri DNA from the multicloning site of the mini-CTX plasmid (15). Probes were purified and labeled at both ends using [γ32-P]ATP (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ) and T4 polynucleotide kinase (New England Biolabs). The binding reaction mixtures contained 1 fmol of each probe, LuxR at 7 nM, and 3OC6-HSL at 10 μM in 20 μl of DNA binding buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.4 at 22°C], 50 mM KCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 100 μg/ml bovine serum albumin, and 5% glycerol).

RESULTS

Effects of single- and multiple-nucleotide substitutions on lux box activity in recombinant E. coli cells.

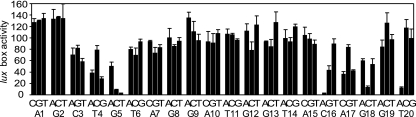

We constructed promoters containing lux boxes with single- and double-nucleotide substitutions. These promoters were used to drive gfp transcription in recombinant E. coli cells. Promoter activity was followed by measuring gfp expression in the presence of 3OC6-HSL. In the first analysis, we tested all possible single-substitution lux box mutations (Fig. 1). In the presence of LuxR and 3OC6-HSL, most substitutions at most positions were well tolerated. Substitutions at positions 3, 4, 5, 16, 17, and 18 resulted in significant loss of activity, as did a specific mutation of T20 to A. Position T20 overlaps the −35 RNA polymerase binding region (7). Thus, the T-to-A mutation at this position might have affected RNA polymerase binding rather than LuxR activity.

FIG. 1.

Effects of single-base-substitution lux box mutations on promoter activity. Every nucleotide in the lux box was replaced with the three other ones. The sequence of a wild-type lux box and the nucleotide numbering system used are shown on the bottom, and activity is expressed as percent of wild-type activity. Experiments were performed with recombinant E. coli cells containing the LuxR expression vector pHV402 and a plasmid containing a lux promoter-gfp transcriptional fusion with a lux box nucleotide substitution as indicated. Cultures were grown with 3OC6-HSL. The results represent the means of the results of three independent experiments, and the error bars represent standard deviations from the means.

The analysis of single-base substitutions in the lux box indicates that positions 3 to 5 and 16 to 18 are important for appropriate LuxR binding but, individually, the other bases are not. To learn more about the nature of the LuxR interactions with positions 3 to 5 and 16 to 18, we analyzed mutant lux boxes with double mutations in these critical positions that retained their dyad symmetry (Table 1). The activity of promoters with these symmetrical mutations was greatly reduced compared to the activity of the wild-type promoter or promoters with single substitutions at one of these positions. We believe that this evidence suggests that C3, T4, G5, C16, A17, and G18 represent areas where LuxR interacts physically with the DNA. If a loss of activity in the single-base-change analysis resulted from disruption of dyad symmetry, one would expect that the double mutants in which dyad symmetry was maintained would show higher activity than the single-substitution lux box mutants. This was not the case. As a control for these experiments, we examined lux boxes with double mutations in bases in which single substitutions did not appear to affect LuxR activity. These mutations also maintained dyad symmetry, and lux boxes with these mutations showed substantial activity (Table 1). This is consistent with the idea that specific interactions of LuxR with these bases are not critical for LuxR function.

TABLE 1.

Double mutations in lux box critical bases that conserve the palindrome cause severe loss of promoter function

| lux box nucleotide substitution(s) | Percent (±SD) of wild-type activity |

|---|---|

| Critical-base substitutionsa | |

| C3A | 70 (12) |

| G18T | 54 (9) |

| C3A, G18T | 2.4 (0.5) |

| C3G | 82 (5) |

| G18C | 14 (2) |

| C3G, G18C | 0.1 (0.4) |

| C3T | 58 (6) |

| G18A | 60 (3) |

| C3T, G18A | 21 (1) |

| T4A | 39 (5) |

| A17T | 42 (2) |

| T4A, A17T | <0.1 |

| T4C | 79 (7) |

| A17G | 84 (5) |

| T4C, A17G | 21 (4) |

| T4G | 28 (3) |

| A17C | 36 (5) |

| T4G, A17C | <0.1 |

| G5C | 9 (1) |

| C16G | 43 (8) |

| G5C, C16G | 0.3 (0.3) |

| Noncritical-base substitutions | |

| A7T | 84 (5) |

| T14A | 99 (15) |

| A7T, T14A | 67 (12) |

| A10C | 94 (18) |

| T11G | 96 (2) |

| A10C, T11G | 77 (4) |

| A10T | 108 (6) |

| T11A | 107 (8) |

| A10T, T11A | 91 (0.4) |

The critical bases are positions 3 to 5 and 16 to 18 of the lux box.

Does a palindrome with conservation at positions 3 through 5 and 16 through 18 retain activity?

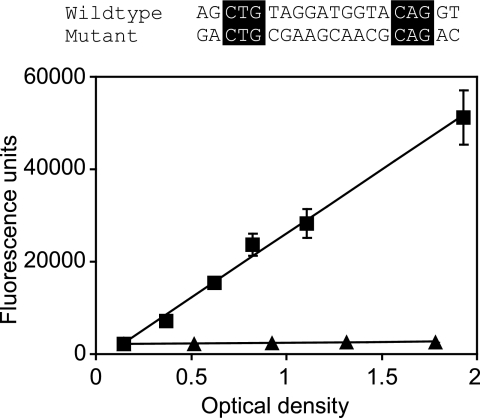

To address the question of whether a palindrome with conservation at the critical positions retains activity, we created a single lux box with changes in the 14 positions shown by the experimental results depicted in Fig. 1 to tolerate substitutions. The mutant lux box was designed such that dyad symmetry was maintained, purines were substituted for purines, and pyrimidines were substituted for pyrimidines. A promoter with this lux box showed no detectable activation by LuxR and 3OC6-HSL (Fig. 2). Thus, at least some of the residues in regions flanking positions 3 to 5 and 16 to 18 are important for lux box function. The results are in some ways reminiscent of those obtained for the lux box-like element to which the A. tumefaciens TraR protein binds (27), where bases equivalent to the lux box positions 3 to 5 and 16 to 18 make direct contact with the transcription factor and the intervening bases serve as a noncontacted spacer. The spacer region undergoes bending upon TraR binding, and this bending is thought to be important for high-affinity TraR-DNA binding.

FIG. 2.

Activity of a palindromic lux box containing substitutions in all nucleotides except those at positions 3 to 5 and 16 to 18. An alignment of the wild-type and mutant lux box sequences is shown. The unchanged nucleotides are boxed. Transcription was monitored in recombinant E. coli cells containing pHV402 and the appropriate lux promoter-gfp fusion plasmid. The activities of the wild-type lux box (squares) and the mutant lux box (triangles) are shown as a function of the optical density of the culture (at 600 nm). The results represent the means of the results of three independent experiments, and the error bars represent standard deviations.

Identification of a 3OC6-HSL-independent lux box.

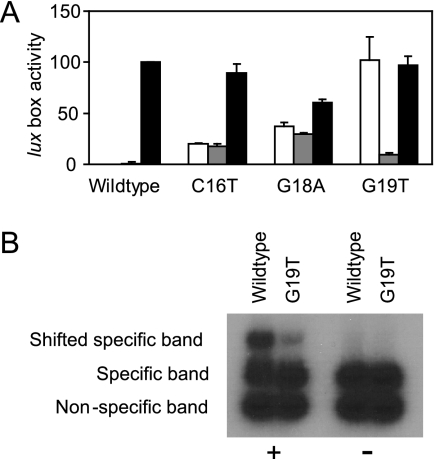

The data shown in Fig. 1 establish that in the presence of LuxR and 3OC6-HSL, many mutant promoters retain considerable activity. However, these results do not demonstrate that activity is dependent upon 3OC6-HSL. Therefore, we tested the dependence of these promoters on 3OC6-HSL by performing control experiments in which the recombinant E. coli strains were grown without added 3OC6-HSL. In almost every case, the promoter activity was absolutely dependent upon the presence of the signal (data not shown), but there were three notable exceptions. Two of these promoters, one with a C16T lux box mutation and the other with a G18A mutation, showed limited activity, and the activity was not only 3OC6-HSL independent, but it was also LuxR independent (Fig. 3A). We suggest that these promoters were better recognized by RNA polymerase than was the wild-type promoter. The more-interesting case was the G19T mutation. The promoter with this mutation was exquisitely dependent upon LuxR, but the LuxR response was 3OC6-HSL independent (Fig. 3A). This is an unexpected phenotype, and we do not have an explanation for how a lux box mutation can result in 3OC6-HSL-independent LuxR activity. One idea is that this mutation creates a high-affinity binding target for LuxR. However, the results of in vitro DNA binding experiments are not consistent with this model. The results presented in figure 3B show that binding of purified LuxR to both the wild-type and the G19T promoter depends on 3OC6-HSL. The absence of LuxR binding to the nonspecific probe in the reactions indicates that binding is DNA sequence specific.

FIG. 3.

3OC6-HSL-independent activity of lux box mutants. (A) In vivo transcriptional-fusion analysis of selected lux box mutants. Transcription was monitored as green fluorescent protein fluorescence in E. coli cells containing a lux promoter-gfp fusion plasmid with the indicated lux box. White bars are results for cells containing the LuxR expression vector pHV402 grown without 3OC6-HSL, gray bars are results for cells without pHV402 grown with 3OC6-HSL, and black bars are results for cells containing pHV402 grown with 3OC6-HSL. Data are presented as percent of the activity in cells with the wild-type lux box plasmid and pHV402 grown with 3OC6-HSL. The results are the means of the results of three independent experiments, and the error bars show standard deviations. (B) In vitro binding of purified LuxR to the wild-type lux box and the G19T mutant lux box with 3OC6-HSL (+) or without 3OC6-HSL (−). Specific probes were generated by PCR amplification of promoter regions using the transcriptional-fusion plasmids as templates. The nonspecific probe was obtained by PCR amplification of the multicloning site of the mini-CTX plasmid (15).

Construction of a minimal lux box consensus sequence and identification of lux boxes for 3OC6-HSL-regulated promoters.

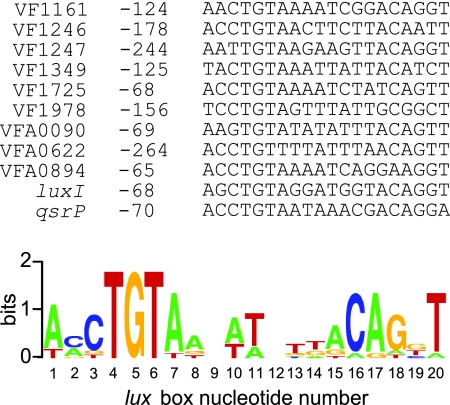

In a previous publication, we used microarray technology to identify 10 non-lux transcriptional units that are directly activated by LuxR and 3OC6-HSL (1). Curiously, only one of these transcripts had an identifiable lux box promoter element (1). Based on the results of our single-substitution mutational analysis (Fig. 1) we propose that the minimal sequence defining a lux box is [N3]YR[N10]YRDNB, where N is any nucleotide; Y is C or T; R is A or G; D is A, G, or T; and B is C, G, or T. Not all sequences that conform to this set of rules will function as a lux box, but we believe that most lux boxes will conform to this sequence. We searched the nine LuxR-activated promoters for which we could not previously identify a lux box by using the minimal lux box sequence described above and Regulatory Sequence Analysis Tools (http://rsat.ulb.ac.be/rsat/) (26). Our minimal lux box is highly degenerate. So, as expected, multiple sites were found in each promoter region. Thus, we applied the following additional criteria: First, because we learned that mutant lux boxes with substitutions in more than one of the critical bases at positions 3 to 5 and 16 to 18 showed little or no activity, we filtered the search results so that a minimum of 5 of these 6 bases were conserved. We then rated the remaining candidate lux boxes according to two criteria: (i) the number of bases that formed a palindrome and (ii) the number of bases that were the same as in the wild-type (luxI) lux box. All promoters searched contained lux boxes with at least 8 bases forming a palindrome and 11 bases conserved with the wild-type lux box (Fig. 4), and these sequences were studied further.

FIG. 4.

Predicted lux boxes found in the promoters of 3OC6-HSL-activated genes. The distances of the lux box elements from the translational start sites of the downstream open reading frames are indicated. The sequence logo shown was constructed based on the lux boxes found using WebLogo (http://weblogo.berkeley.edu/).

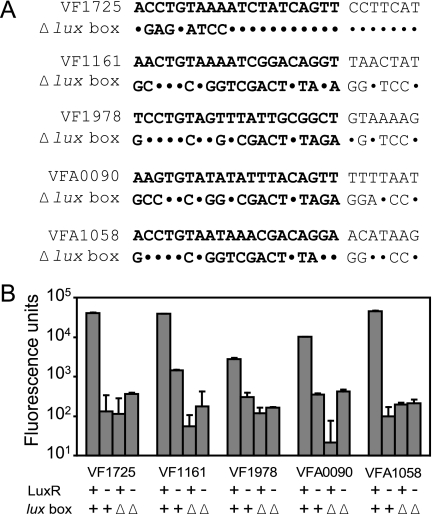

To test whether putative lux boxes were required for LuxR activation of the quorum-sensing-controlled promoters, we generated two promoter fusions to gfp for five of the transcriptional units, VF1161, VF1725, VF1978, VFA0090, and VFA1058. One fusion extended from downstream of the ATG codon of the first gene in each unit to immediately upstream of the predicted lux box. The other fusion lacked either part of or the entire putative lux box (Fig. 5A). We measured promoter activity in recombinant E. coli cells with or without a LuxR expression vector. In all cases, there was LuxR-dependent activation of promoters with full lux box-like elements and there was not LuxR-dependent activation of promoters with deletions in the lux box-like sequences (Fig. 5B). It is possible that some of the lux box deletions constructed have affected RNA polymerase binding to the promoter because the lux box overlaps the −35 region (7). Nevertheless, our data indicate that the regions deleted are required for promoter activity and that the activity of the construct containing the lux box-like element is strictly dependent upon LuxR. These data support the view that the elements we identified are involved in LuxR-driven promoter activation.

FIG. 5.

Mutational analysis of putative lux boxes of previously identified V. fisheri quorum-controlled promoters (1). (A) DNA sequences of putative lux boxes found in the promoter regions of the genes indicated and deletion mutants (Δlux box). Downstream DNA was identical in wild-type and mutant constructs. The lux box elements are in bold. Nucleotides unchanged in the mutant are shown as dots. (B) Promoter activity of constructs shown in panel A. Experiments were performed with recombinant E. coli cells, and data are given as fluorescence units (fluorescence per optical density unit). Activity in the presence (+) or absence (−) of LuxR is shown. Bars labeled “lux box +” represent the activity of wild-type constructs, whereas “lux box Δ” designates the activity of the Δlux box constructs shown in panel A. All fusions were tested in the presence of 3OC6-HSL. The results are the means of the results of three independent experiments. Error bars show standard deviations of the means.

DISCUSSION

The induction of V. fischeri luminescence by LuxR and 3OC6-HSL serves as a quorum-sensing paradigm. We understand many details about how 3OC6-HSL is synthesized by V. fischeri, how it exits and enters cells, how it interacts with the transcription factor LuxR, and how LuxR interacts with its binding site in the promoter region of the lux operon (10, 22, 28). However, we know relatively little about elements of the binding site, the lux box, that is required for LuxR activation of the lux operon. We recently learned that a number of genes other than the lux genes are activated by LuxR and 3OC6-HSL (1). Although evidence indicates that they are activated by LuxR directly, there is no apparent lux box in the promoter regions of most of these genes (1). The systematic mutational analysis described here has revealed information about the roles of different elements in the lux box and has allowed us to identify LuxR binding targets in quorum-sensing-activated V. fischeri genes other than the lux genes.

Our analysis of mutant lux boxes with single-base substitutions (Fig. 1) indicates that LuxR makes direct contact with the lux box in the regions of nucleotides 3 to 5 and 16 to 18. Single-base substitutions in these regions reduce activity substantially. Residual activity could be a consequence of the affinity of the unaltered half site to interact with one monomer of a LuxR dimer. In support of this, mutants with nucleotide substitutions in both half sites in these critical regions (nucleotides 3 to 5 and 16 to 18), but not in other regions, have a severely reduced activity (Table 1). We note that a consensus sequence derived from lux boxes of a number of V. fischeri strains isolated from a variety of marine environments shows conservation of nucleotides C3, T4, G5, C16, A17, and G18 (1). By examining the activity of lux boxes with multiple mutations in the sequence flanking nucleotides 3 to 5 and 16 to 18, we have shown that although these regions may not be involved in direct interactions with LuxR, their sequence is important for activity (Fig. 2). We believe our findings are consistent with the model for TraR interaction with regulatory DNA. The A. tumefaciens TraR protein interaction with regulatory DNA is the only other example of a LuxR homolog that has been studied in detail (27). In fact, the structure of TraR bound to the regulatory region has been deduced (29), and the structural data, together with a detailed binding site mutational analysis, provide a compelling view of the interactions. Nucleotides equivalent to lux box residues 3 to 5 and 16 to 18 are in close contact with TraR, and the intervening sequence provides a proper bend for the protein to interact with the binding site (27).

A few single-nucleotide substitutions increased 3OC6-HSL-independent transcription. For the most part, the phenotypes of these mutant promoters can be explained as resulting from an increased affinity for RNA polymerase. However, one mutant with a lux box G19T substitution shows an unexpected LuxR-dependent but 3OC6-HSL-independent activity (Fig. 3A). One explanation for this curious phenotype might be that the mutant lux box has an increased affinity for LuxR. We assume that LuxR dimers and monomers are in equilibrium and that 3OC6-HSL shifts the equilibrium toward dimers. If the G19T mutant lux box had a much greater affinity for LuxR dimers than did the wild-type lux box, then the low level of LuxR dimers that we predict would exist in the absence of 3OC6-HSL might be sufficient for promoter activation. To test this hypothesis, we performed in vitro DNA binding experiments (Fig. 3B). The results of these experiments did not support the idea that the mutant lux box had a greater affinity for LuxR than did the wild-type lux box. Because LuxR is difficult to handle in vitro (25), the results of DNA binding experiments are more difficult to interpret than are those of experiments with TraR (30) or the Pseudomonas aeruginosa LasR (21), for example. Therefore, the most-critical experiments could not be performed and the results of our in vitro studies must be interpreted with caution.

The LuxR-type regulator LasR binds to DNA sequences with homology to lux boxes, and the binding sites are commonly referred to as las boxes (18, 21). Recently, it has been shown that LasR is also capable of functional binding to specific DNA regions with no apparent homology to las boxes (21). This indicates that there is significant plasticity in LasR binding sites and that the utilization of consensus sequences and bioinformatics tools to predict such binding sites may prove difficult. Accordingly, our mutational studies revealed that there can be considerable sequence plasticity in functional lux boxes. Nevertheless, there is significant conservation in bases 3 to 5 and 16 to 18 of this 20-base-pair inverted repeat. We used this information to analyze promoter regions of LuxR-regulated genes for which we could not previously identify lux box-like elements (1). Our search involved two steps. First, we used computational tools to identify degenerate lux box-like sequences in the promoters for such genes. Second, we filtered the sequences we found to identify those which had at least 5 of the 6 bases in the regions of positions 3 to 5 and 16 to 18 conserved and we identified the sequence that showed the greatest extent of inverted repeat match. By doing so, we were able to identify putative lux boxes in the promoters of all 3OC6-HSL-activated genes described previously (Fig. 4) (1). To determine whether our search-and-filter approach identified real LuxR binding sites, we constructed and tested transcriptional fusions that contained or lacked the predicted lux box elements of five of the promoters (Fig. 5). Our results showed that the predicted lux boxes are required for LuxR-dependent promoter activation. This provides evidence that the search revealed LuxR binding sites. The results presented in this study broaden our understanding of LuxR-DNA interactions and how they affect promoter activity.

Acknowledgments

We thank Mark Urbanowski for his technical advice and Amy Schaefer for critical reading of the manuscript. Escherichia coli DH12S was a kind gift from Bradley D. Jones (The University of Iowa).

This work was supported by a grant from the W. M. Keck Foundation.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 14 December 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Antunes, L. C. M., A. L. Schaefer, R. B. R. Ferreira, N. Qin, A. M. Stevens, E. G. Ruby, and E. P. Greenberg. 2007. A transcriptome analysis of the Vibrio fischeri LuxR-LuxI regulon. J. Bacteriol. 1898387-8391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bassler, B. L., and R. Losick. 2006. Bacterially speaking. Cell 125237-246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bassler, B. L., M. Wright, and M. R. Silverman. 1994. Multiple signalling systems controlling expression of luminescence in Vibrio harveyi: sequence and function of genes encoding a second sensory pathway. Mol. Microbiol. 13273-286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boettcher, K. J., and E. G. Ruby. 1990. Depressed light emission by symbiotic Vibrio fischeri of the sepiolid squid Euprymna scolopes. J. Bacteriol. 1723701-3706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Devine, J. H., G. S. Shadel, and T. O. Baldwin. 1989. Identification of the operator of the lux regulon from the Vibrio fischeri strain ATCC7744. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 865688-5692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eberhard, A., A. L. Burlingame, C. Eberhard, G. L. Kenyon, K. H. Nealson, and N. J. Oppenheimer. 1981. Structural identification of autoinducer of Photobacterium fischeri luciferase. Biochemistry 202444-2449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Egland, K. A., and E. P. Greenberg. 1999. Quorum sensing in Vibrio fischeri: elements of the luxI promoter. Mol. Microbiol. 311197-1204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Engebrecht, J., K. Nealson, and M. Silverman. 1983. Bacterial bioluminescence: isolation and genetic analysis of functions from Vibrio fischeri. Cell 32773-781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Engebrecht, J., and M. Silverman. 1984. Identification of genes and gene products necessary for bacterial bioluminescence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 814154-4158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fuqua, C., and E. P. Greenberg. 2002. Listening in on bacteria: acyl-homoserine lactone signalling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 3685-695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fuqua, C., and E. P. Greenberg. 1998. Self perception in bacteria: quorum sensing with acylated homoserine lactones. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 1183-189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fuqua, C., M. R. Parsek, and E. P. Greenberg. 2001. Regulation of gene expression by cell-to-cell communication: acyl-homoserine lactone quorum sensing. Annu. Rev. Genet. 35439-468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fuqua, C., S. C. Winans, and E. P. Greenberg. 1996. Census and consensus in bacterial ecosystems: the LuxR-LuxI family of quorum-sensing transcriptional regulators. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 50727-751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gray, K. M., L. Passador, B. H. Iglewski, and E. P. Greenberg. 1994. Interchangeability and specificity of components from the quorum-sensing regulatory systems of Vibrio fischeri and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 1763076-3080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hoang, T. T., A. J. Kutchma, A. Becher, and H. P. Schweizer. 2000. Integration-proficient plasmids for Pseudomonas aeruginosa: site-specific integration and use for engineering of reporter and expression strains. Plasmid 4359-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Johnson, D. C., A. Ishihama, and A. M. Stevens. 2003. Involvement of region 4 of the sigma70 subunit of RNA polymerase in transcriptional activation of the lux operon during quorum sensing. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 228193-201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miller, W. G., J. H. Leveau, and S. E. Lindow. 2000. Improved gfp and inaZ broad-host-range promoter-probe vectors. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 131243-1250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rust, L., E. C. Pesci, and B. H. Iglewski. 1996. Analysis of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa elastase (lasB) regulatory region. J. Bacteriol. 1781134-1140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 20.Schaefer, A. L., D. L. Val, B. L. Hanzelka, J. E. Cronan, Jr., and E. P. Greenberg. 1996. Generation of cell-to-cell signals in quorum sensing: acyl homoserine lactone synthase activity of a purified Vibrio fischeri LuxI protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 939505-9509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schuster, M., M. L. Urbanowski, and E. P. Greenberg. 2004. Promoter specificity in Pseudomonas aeruginosa quorum sensing revealed by DNA binding of purified LasR. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 10115833-15839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smith, D., J. H. Wang, J. E. Swatton, P. Davenport, B. Price, H. Mikkelsen, H. Stickland, K. Nishikawa, N. Gardiol, D. R. Spring, and M. Welch. 2006. Variations on a theme: diverse N-acyl homoserine lactone-mediated quorum sensing mechanisms in gram-negative bacteria. Sci. Prog. 89167-211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stevens, A. M., N. Fujita, A. Ishihama, and E. P. Greenberg. 1999. Involvement of the RNA polymerase alpha-subunit C-terminal domain in LuxR-dependent activation of the Vibrio fischeri luminescence genes. J. Bacteriol. 1814704-4707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thompson, J. D., D. G. Higgins, and T. J. Gibson. 1994. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 224673-4680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Urbanowski, M. L., C. P. Lostroh, and E. P. Greenberg. 2004. Reversible acyl-homoserine lactone binding to purified Vibrio fischeri LuxR protein. J. Bacteriol. 186631-637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van Helden, J. 2003. Regulatory sequence analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 313593-3596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.White, C. E., and S. C. Winans. 2007. The quorum-sensing transcription factor TraR decodes its DNA binding site by direct contacts with DNA bases and by detection of DNA flexibility. Mol. Microbiol. 64245-256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Williams, P., K. Winzer, W. C. Chan, and M. Camara. 2007. Look who's talking: communication and quorum sensing in the bacterial world. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B 3621119-1134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang, R. G., T. Pappas, J. L. Brace, P. C. Miller, T. Oulmassov, J. M. Molyneaux, J. C. Anderson, J. K. Bashkin, S. C. Winans, and A. Joachimiak. 2002. Structure of a bacterial quorum-sensing transcription factor complexed with pheromone and DNA. Nature 417971-974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhu, J., and S. C. Winans. 1999. Autoinducer binding by the quorum-sensing regulator TraR increases affinity for target promoters in vitro and decreases TraR turnover rates in whole cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 964832-4837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]