Abstract

Coxiella burnetii, an obligate intracellular parasite with a worldwide distribution, is the causative agent of Q fever in humans. We tested a total of 368 samples (placental bits, genital swabs, fecal swabs, and urine and serum samples) collected from women (n = 74) with spontaneous abortions for C. burnetii by a PCR assay targeting IS1111, the repetitive transposon-like region of C. burnetii (trans-PCR); real-time PCR; an indirect immunofluorescence assay (IFA); and the isolation of the pathogen. The IFA showed seropositivity for 25.68% of the women with spontaneous abortions, whereas trans-PCR and real-time PCR each detected the pathogen in 21.62% of cases. Overall, 25.68% of the subjects were positive by one or more assays. Real-time PCR showed a slightly higher level of sensitivity than trans-PCR. With the IFA as the reference, the two PCR assays showed a higher level of sensitivity (84.21%) than pathogen isolation (26.31%), while both the PCR assays and pathogen isolation were specific (100%). The detection of high numbers of C. burnetii cells in clinical samples and the frequent association of the pathogen with cases of spontaneous abortions observed in this study revealed that Q fever remains underdiagnosed and that the prevalence in India is underestimated.

Q fever is an important occupational zoonotic disease caused by the obligate intracellular bacterium Coxiella burnetii and has great public health significance worldwide (21). C. burnetii is considered to be a potential weapon for bioterrorism (9, 10, 12, 15, 23) and has been classified as a critical biological agent into risk group 3, requiring biosafety level 3 containment, by the Centers for Diseases Control and Prevention (2, 7). The most commonly identified sources of human infection are farm animals, especially cattle, goats, and sheep (4), which constitute the best-known reservoirs of C. burnetii (21, 23, 24). C. burnetii infection of pregnant women can provoke placentitis and often lead to premature birth, growth retardation, spontaneous abortion, or fetal death (29). The disease is usually benign, but mortality occurs in 1 to 11% of patients with chronic Q fever (28).

The isolation of the pathogen is a reliable diagnostic method, but it remains time-consuming and hazardous and requires biosafety level 3 practices (25). Therefore, the diagnosis of C. burnetii infection is usually done by PCR or serological examination (17). A PCR assay performed with primers based on IS1111, the repetitive, transposon-like element (trans-PCR) (37), has been found to be highly specific and sensitive for the detection of C. burnetii in different clinical samples (3, 4, 19). Real-time PCR assays with high levels of sensitivity and specificity have been developed previously (5), and real-time PCR is an excellent method for the detection and quantification of C. burnetii cells in body fluids (32). The real-time PCR targeting the IS1111 gene has been employed previously as a method for the detection and quantification of C. burnetii cells in bulk tank milk (15) and clinical samples including peripheral blood mononuclear cells (S. V. S. Malik and M. P. Yadav, presented at the meeting of the Task Force on Rickettsioses, Indian Council of Medical Research, New Delhi, India, 2002). The Sybr green I-based real-time PCR assay has also been employed as an alternative to antibiotic susceptibility testing of C. burnetii Nine Mile, phase I (5, 6). Usually, two distinct types of antibodies are produced in a temporal manner; phase II antibodies appear early in infection, while phase I antibodies arise later and usually only at relatively low levels, except in cases of the chronic form of the disease, in which the levels tend to become greatly elevated (8). An immunofluorescence assay (IFA) is currently used as the reference method for the serodiagnosis of Q fever, and it can differentiate antibodies to phase I and phase II variants in immunoglobulin G (IgG), IgM, and IgA fractions (11, 26, 35, 38).

The objectives of the present study were to investigate the prevalence of Q fever infection in women with spontaneous abortions by employing a serological method (IFA) and molecular methods (trans-PCR and/or real-time PCR), to quantify the C. burnetii cells excreted in clinical samples by real-time PCR and pathogen isolation, and to compare the efficacies of different tests.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Standard strain of C. burnetii.

Phenol-killed, purified, and lyophilized cells of the C. burnetii Nine Mile, phase I, strain (RSA 493) were procured from Rudolf Toman, Institute of Virology, Slovak Academy of Sciences, Bratislava, Slovak Republic.

Samples.

A total of 368 samples comprising placental bits (74 samples), genital swabs (74 samples), fecal swabs (74 samples), urine samples (72 samples), and sera (74 samples) from women (n = 74) with cases of spontaneous abortion were collected from various hospitals in northern India. The clinical samples were collected aseptically in screw-cap sterile vials containing 10 ml of sterile Bovarnick's buffer (74.62 g of sucrose, 0.218 M; 0.52 g of KH2PO4, 0.0038 M; 1.64 g of K2HPO4, 0.0072 M; 0.82 g of Na glutamate, 0.0049 M; 1,000 ml of distilled water; 1% bovine serum albumin; and appropriate antibiotics) (33) as the transport medium. The urine samples were collected directly into sterile vials. The samples were transported to the laboratory under chilled conditions and stored at −20°C until being processed.

DNA extraction.

DNA from the C. burnetii Nine Mile, phase I, strain and clinical samples was purified using the DNeasy tissue kit 250 per the instructions of the manufacturer (Qiagen). Briefly, the placental tissue (25 mg) was cut into small pieces and processed for DNA extraction. Genital swab samples collected in Bovarnick's buffer were extensively washed in 10 ml of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; 0.01 M, pH 7.4) solution. A total of 1 ml of the sample solution was treated with proteinase K and processed for DNA purification. The suspensions of fecal swabs in 10 ml of Bovarnick's buffer were stirred, and 1-ml aliquots were processed for DNA extraction. The aliquots were added to suitable lysis buffer and treated overnight at 55°C with proteinase K (200 μg/ml). The enzyme was then inactivated by being heated to 100°C for 10 min. To remove the PCR-inhibitory substances, the lysed solution was centrifuged at 13,000 × g for 5 min and the supernatant was mixed with a 0.525 volume of ethanol (3) before being processed for DNA extraction. The DNA was quantified by using an ND 100 spectrophotometer (Nanodrop Technologies).

Trans-PCR.

A PCR assay targeting IS1111, an element of C. burnetii (5), was used for the detection of C. burnetii in clinical samples. The primers trans-1 (5′-TAT GTA TCC ACC GTA GCC AGT C-3′), trans-2 (5′-CCC AAC AAC ACC TCC TTA TTC-3′), trans-3 (5′-GTA ACG ATG CGC AGG CGA T-3′), and trans-4 (5′-CCA CCG CTT CGC TCG CTA-3′) used in this study were synthesized by Sigma-Genosys. The trans-1 and trans-2 primers, designed as a pair of 22- and 21-residue oligonucleotide primers (4, 19), and the trans-3 and trans-4 primers (19) were based on the published data sequence of a transposon-like repetitive region of the C. burnetii genome (14). The trans-1 and trans-2 (set I) and trans-3 and trans-4 (set II) primers were designed to amplify a 687-bp fragment and a 243-bp fragment of the transposon-like repetitive element, respectively.

The trans-PCR assay was performed as described previously (4) with suitable modifications. The PCR mixture (50 μl) included 5.0 μl of 10× PCR buffer (100 mM Tris-HCl buffer, pH 8.3, containing 500 mM KCl, 15 mM MgCl2, and 0.01% gelatin), 200 μM deoxynucleoside triphosphate mix, 2 μM (each) primers, 0.5 U of Taq DNA polymerase, 5 μl of template DNA, and sterilized MilliQ water to make up the reaction mixture volume. The DNA amplification reaction was performed in a Mastercycler gradient thermocycler (Eppendorf, Germany). The cycling conditions for PCR included an initial denaturation of DNA at 95°C for 2 min, followed by five cycles at 94°C for 30 s, 66 to 61°C (the temperature was decreased by 1°C between consecutive steps) for 1 min, and 72°C for 1 min. These cycles were followed by 40 cycles consisting of 94°C for 30 s, 61°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 1 min and then a final extension step of 10 min at 72°C. The two sets of primers for C. burnetii genes were amplified under similar PCR conditions and in similar amplification cycles.

The standardized trans-PCR was assessed for its sensitivity to detect C. burnetii DNA in a 10-fold dilution (10−1 to 10−5) of a known concentration (70 ng/μl) of DNA from the C. burnetii Nine Mile, phase I, strain. The template DNA was prepared from killed cells (1 mg) of the C. burnetii strain as mentioned above. The sensitivity of trans-PCR for the detection of C. burnetii in artificially contaminated samples was evaluated by adding different concentrations of DNA from the C. burnetii Nine Mile, phase I, strain to clinical samples except sera (placental bits, genital swabs, fecal swabs, and urine samples) from Q fever-free women as described above. The template DNA was prepared from 1-ml aliquots used for the purification of C. burnetii Nine Mile, phase I, strain DNA from spiked samples by using the DNeasy tissue kit 250. The PCR was performed, and the products were analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis.

The standardized trans-PCR assay was used for the detection of C. burnetii DNA in placental bits, genital swabs, fecal swabs, and urine samples.

qPCR.

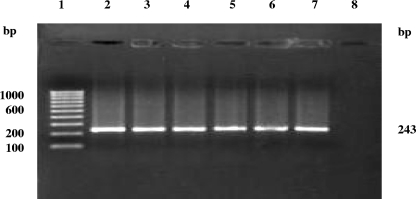

The detection as well as the quantification of C. burnetii cells in clinical samples from women was carried out by a quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) assay using the primer set (trans-3 and trans-4) that generated an amplification product of 243 bp.

The aliquot (2 μl) of DNA extracted from the C. burnetii Nine Mile, phase I, strain was used as a DNA template in the PCR mixture for the standardization of the qPCR. The qPCR assay was performed with brilliant Sybr green master mix (Stratagene) and an Mx3000P spectrofluorometric thermal cycler operated by MxPro qPCR software. The qPCR was run in duplicate, in each case with a total volume of 20 μl containing 5 pmol each of the forward and reverse primers, 2 μl of template DNA, 10 μl of Sybr green qPCR master mix, and 7 μl of nuclease-free PCR-grade water. The PCR conditions included 95°C for 10 min (segment I); 40 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 61°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 1 min (segment II), with the degree of fluorescence recorded at the end point of each cycle; and a dissociation (melting) curve consisting of 95°C for 30 s, followed by 61°C for 30 s, a gradual increase from 61 to 95°C at increments of 2°C per min, and lastly, 95°C for 30 s (segment III). After the completion of the dissociation (melting) curve, the melting temperature was recorded as 83.6°C. The PCR product was confirmed by 1.5% agarose gel electrophoresis with ethidium bromide.

The genome copy numbers per microliter for a known concentration (20 ng/μl) of DNA from the C. burnetii Nine Mile, phase I, strain were calculated to construct a standard curve for the determination of initial copy numbers per the method used previously (6). After the number of DNA copies (107) in the known concentration (20 ng/μl) was worked out, the DNA was diluted to prepare 10-fold serial dilutions ranging from 10−1 to 10−7. The standard curve in terms of a regression line equation was drawn by plotting the known numbers of DNA copies in the dilutions against the threshold cycles. Finally, the numbers of C. burnetii DNA copies in the clinical samples were estimated based on the regression line equation of the standard curve.

The standardized qPCR was used for the detection as well as the quantification of C. burnetii DNA copies in clinical samples (placental bits, genital swabs, fecal swabs, and urine samples) from women. The DNA copies in each clinical sample were quantified by comparing the amount of C. burnetii DNA against the reference value per the standard curve.

IFA.

Antigens, Dolfinin Q fever indirect microimmunofluoresence phase I and II sera, and the standard sera, namely, Dolfinin C. burnetii-positive rabbit serum and C. burnetii-negative rabbit serum, were procured from Dolfin, Spol, Slovakia. A goat anti-human IgG-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) immunoconjugate (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, India) was used. The IFA was performed per the protocol provided by Dolfin, Spol, Slovakia.

Detection of phase I antibodies.

The phase I antigen was used for the detection of elevated levels of C. burnetii phase I antibodies (IgG and IgA) in humans. Briefly, slides were cleaned with an ethanol-acetone mixture (consisting of equal volumes of the components). A working dilution (1:5) of the antigen was prepared in a suspension of 3% egg yolk sac in PBS (0.01 M; pH 7.4). A drop of antigen was placed onto each well of a six-well slide, and the slides were allowed to dry at room temperature for 30 min. The slides were fixed in acetone for 15 min.

Procedure for IgG testing.

All the reagents were brought to room temperature before use. Serum samples were diluted 1:25 by adding 10 μl of serum to 240 μl of PBS, and twofold dilutions (1:50 to 1:3,200) were made using equal volumes of 1:25 serum and PBS. The control sera were diluted in a similar way. The serum dilutions were added to wells (20 μl/well). The procedure was repeated for positive and negative controls. The slides were incubated at 37°C for 30 min in a humidified chamber and then removed from the chamber and immersed twice in PBS for 5 min each time. The slides were dipped briefly in deionized water and air dried. An Evans blue solution, prepared by mixing 50 μl of Evans blue (0.001%) with 5 ml of PBS, was used to dilute the IgG-FITC conjugate (1:200). The diluted IgG-FITC conjugate (20 μl) was added to each well, and the slides were placed in a humidified chamber for incubation at 37°C for 30 min. The slides were then immersed twice in PBS for 5 min each time, dipped briefly in deionized water, and finally air dried. The coverslips were mounted over 1 drop of mounting medium. The slides were viewed as soon as possible at a total magnification of ×400 with a fluorescence microscope.

Procedure for IgM and IgA testing.

All reagents were brought to room temperature before use. Serum samples (5 μl) were mixed with PBS (5 μl) and IgG sorbent (10 μl), i.e., rheumatoid factor absorbent (Dade Behring, Marburg, Germany) dissolved in 1.5 ml of deionized water. The reagents were incubated with agitation at room temperature for 15 min. Subsequently, rheumatoid factor absorbent (20 μl) was added to the mixture, and the mixture was incubated with shaking at room temperature for 15 min. PBS (85 μl) was then added to prepare a final dilution of 1:25, and the mixture was centrifuged at 12,000 to 15,000 rpm for 9 min. The sorbent-treated serum samples (65 μl) were diluted 1:2 with PBS (65 μl) to prepare a final dilution of 1:50, and subsequently, twofold dilutions up to 1:200 in PBS were made. Positive and negative controls were sorbent treated and worked up as the serum samples. The serum dilutions were added to wells (20 μl/well). The procedure was repeated for positive and negative controls. The slides were incubated at 37°C for 30 min in a humidified chamber and then immersed twice in PBS for 5 min each time, dipped briefly in deionized water, and air dried. An Evans blue solution, prepared by mixing 50 μl of Evans blue (0.001%) with 5 ml of PBS, was used to dilute the IgM- or IgA-FITC conjugate (1:100). The diluted IgM- or IgA-FITC conjugate (20 μl) was added to each well, and the slides were incubated in a humidified chamber at 37°C for 30 min. The slides were then immersed twice in PBS for 5 min each time, dipped briefly in deionized water, and finally air dried. The coverslips were mounted over 1 drop of mounting medium, and the slides were viewed as soon as possible at a total magnification of ×400 with a fluorescence microscope.

Detection of phase II antibodies.

The phase II antigen was used for the detection of C. burnetii phase II antibodies (IgG as well as IgM and IgA) in the early stages of infection for the diagnosis of acute Q fever. The procedure was followed as described above for the detection of phase I antibodies.

The serum samples from women were tested for C. burnetii phase I and phase II antibodies by the standardized IFA.

Isolation of C. burnetii.

The isolation of C. burnetii from the clinical samples from women by the chicken embryo inoculation method as described previously (34) was attempted. Embryonated eggs (6 to 7 days old) were procured from the Central Avian Research Institute, Izatnagar, India. The batch of embryonated eggs was tested for the absence of C. burnetii by staining and PCR.

Inocula from different clinical samples were prepared per the method described previously (35) and inoculated into embryonated eggs, and the eggs were observed daily for mortality. The inoculated eggs showing the death of embryos within 6 to 8 days postinoculation were harvested. The impression smears of infected yolk sac membranes (YSM) harvested from chicken embryos were stained with Gimenez's stain and modified Macchiavello's stain for the microscopic demonstration of red inclusion bodies or elementary bodies (EBs) of C. burnetii. The isolates were further confirmed by PCR.

Interpretation of results.

The results of different diagnostic methods (trans-PCR and real-time PCR, IFA, and pathogen isolation) were analyzed to compare the efficacies (sensitivities and specificities) of the methods (25) for the diagnosis of Q fever.

RESULTS

Trans-PCR.

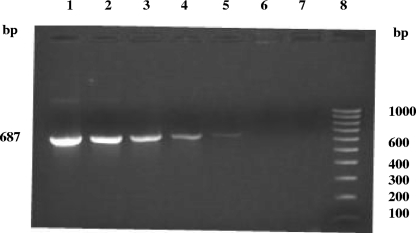

The standardized trans-PCR assay was used for the detection of C. burnetii in clinical samples by employing two sets of primers that specifically allowed the amplification of 687- and 243-bp products. The trans-PCR employing set I primers for C. burnetii, when applied to 10-fold dilutions of a known concentration (70 ng/μl) of DNA from the C. burnetii Nine Mile, phase I, strain as well as of DNA extracted from the artificially contaminated samples, could detect C. burnetii DNA in dilutions of up to 0.007 ng/μl (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Sensitivity of trans-PCR for the detection of various amounts of the C. burnetii standard Nine Mile, phase I, strain (RSA 493) DNA template (687 bp). Lanes: 1 to 6, different dilutions of the DNA template (undiluted [70 ng/μl], 10−1, 10−2, 10−3, 10−4, and 10−5); 7, negative control (no DNA); 8, 100-bp DNA ladder.

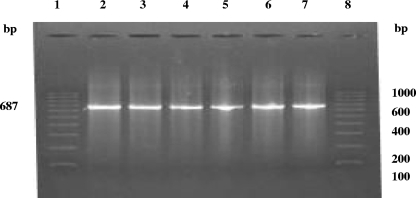

Upon the screening of 294 clinical samples, excluding sera, from 74 women with cases of spontaneous abortion by IS1111-based trans-PCR, C. burnetii could be detected in 29 samples (9 each of placental bits and genital swabs, 5 fecal swabs, and 6 urine samples) from 16 patients (Table 1; Fig. 2 and 3).

TABLE 1.

Comparative efficacies of different methods for the diagnosis of C. burnetii infection in humans with spontaneous abortionsa

| Case | Result from:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trans-PCR | Real-time PCR | IFA | Pathogen isolation | |

| 1 | + | + | + | − |

| 2 | + | + | + | − |

| 3 | − | − | + | − |

| 4 | + | + | + | + |

| 5 | + | + | + | − |

| 6 | + | + | + | − |

| 7 | + | + | + | − |

| 8 | + | + | + | − |

| 9 | + | + | + | − |

| 10 | + | + | + | + |

| 11 | + | + | + | − |

| 12 | − | − | + | − |

| 13 | − | − | + | − |

| 14 | + | + | + | + |

| 15 | + | + | + | + |

| 16 | + | + | + | − |

| 17 | + | + | + | − |

| 18 | + | + | + | + |

| 19 | + | + | + | − |

| Total no. (%) of positive results | 16 (21.62%) | 16 (21.62%) | 19 (25.68%) | 5 (6.75%) |

The cases (19) presented are those of individuals among the 74 patients that were initially tested.

FIG. 2.

Trans-PCR detection of C. burnetii in clinical samples from women with spontaneous abortions. Lanes: 1, 100-bp DNA ladder as a marker; 2, DNA template from the standard C. burnetii Nine Mile, phase I, strain; 3 to 7, DNA of C. burnetii isolates from clinical samples.

FIG. 3.

Trans-PCR detection of C. burnetii DNA in clinical samples from women with spontaneous abortions. Lanes; 1, 100-bp DNA ladder as a marker; 2 to 6, DNA of C. burnetii isolates from clinical samples; 7, DNA template from the standard C. burnetii Nine Mile, phase I, strain; 8, negative control (no DNA).

qPCR.

The qPCR assay specifically allowed the amplification of a 243-bp product from the region corresponding to the IS1111a gene of C. burnetii. The amplification plots and dissociation curves for DNA from the C. burnetii Nine Mile, phase I, strain served as a basis for detecting and quantifying the DNA of C. burnetii in the clinical samples from positive patients.

Clinical samples from all patients found to be positive by trans-PCR and the IFA were further screened by qPCR for the detection as well as the quantification of C. burnetii DNA. The screening of 76 clinical samples, excluding sera (19 each of placental bits, genital swabs, fecal swabs, and urine samples), by qPCR revealed positivity for Q fever in more (33) samples (11 placental bits, 9 genital swabs, 5 fecal swabs, and 8 urine samples) than the screening by trans-PCR.

The numbers of C. burnetii DNA copies in the clinical samples were calculated based on the extrapolation of the threshold cycles of the samples against the standard curve. The numbers of C. burnetii cells detected (expressed as the numbers of DNA copies per microliter) ranged from 1.68 × 102 to 4.16 × 106 in placental tissues, 2.61 × 104 to 8.11 × 104 in genital swabs, 1.13 × 101 to 1.39 × 101 in fecal swabs, and 2.31 × 101 to 6.01 × 101 in urine samples. The highest number of C. burnetii cells (detected as genomic DNA copies) was found in placental tissues, followed by genital swabs, urine samples, and fecal swabs.

IFA.

Upon the screening of sera (74 samples) for phase I and phase II C. burnetii antibodies by the IFA, 19 samples (25.68%) were found to be positive (7 for phase I antibodies and 12 for phase II antibodies) (Table 1), with IgG detected in more samples than IgM and IgA (data not shown).

Isolation of C. burnetii.

Clinical samples (19 each of placental bits, genital swabs, fecal swabs, and urine samples) from the patients found to be positive by trans-PCR, real-time PCR, and/or the IFA were processed and inoculated into 6- to 7-day-old embryonated chicken eggs.

A characteristic mortality pattern of the embryos in the inoculated eggs and the demonstration of typical EBs suggestive of C. burnetii infection in the YSM were observed in five cases (6.75%). In these five cases (cases 4, 10, 14, 15, and 18) in which isolates were recovered from clinical samples (placental bits, genital and fecal swabs, and urine samples), samples from the same patients also showed positivity by PCR and the IFA (Table 1). The examination of impression smears from the YSM of eggs showing mortality revealed characteristic inclusions or EBs, appearing as red intracytoplasmic bodies against a green background of cytoplasm when the smears were stained with Gimenez's stain and as red single or clustered EBs when the smears were stained with modified Macchiavello's stain.

Comparative efficacies of different diagnostic methods.

The efficacies of trans-PCR and real-time PCR, the IFA, and pathogen isolation were compared. The IFA detected the maximum number of positive cases (19), followed by trans-PCR and real-time PCR and pathogen isolation. The pathogen could be isolated in five cases. The percentage of positivity for Q fever among the women was observed to be highest (25.68%) when determined by the IFA, followed by trans-PCR (21.62%), real-time PCR (21.62%), and the isolation of the pathogen (6.75%) (Table 1). Overall, 25.68% of patients (19 of 74) showed positivity for C. burnetii infection in one or more diagnostic tests (Table 1). Upon the comparison of the efficacies of the different diagnostic methods with the IFA as the “gold standard,” the highest level of sensitivity (84.21%) was seen in the case of trans-PCR and real-time PCR, followed by pathogen isolation (26.31%), whereas trans-PCR, real-time PCR, and the isolation of pathogen turned out to have the same level of specificity (100%).

DISCUSSION

Q fever, caused by the rickettsial organism C. burnetii, is an emerging or reemerging rickettsial zoonotic disease worldwide (1). The data in most of the published reports on the prevalence of C. burnetii infection in humans and animals in India are based on results from serosurveys employing capillary agglutination and complement fixation tests, aside from those in the few reports on the isolation of the agent. The present study was undertaken to assess the prevalence of C. burnetii infection in women with spontaneous abortions by employing a serological test and molecular tests, as well as the pathogen isolation method.

In the present study, the trans-PCR assay targeting the IS1111a gene of C. burnetii proved to be highly specific and sensitive for the detection of C. burnetii in clinical samples. Earlier workers found trans-PCR to be highly specific and sensitive for the direct detection of C. burnetii in genital swabs and milk and fecal samples from ewes (3). The high degree of efficacy of the trans-PCR can be attributed to the fact that the targeted region exists in at least 19 copies in the C. burnetii Nine Mile, phase I, genome (14), which gives the trans-PCR a level of sensitivity 100 times higher than that of the PCR assay (3).

The trans-PCR assay could detect a known concentration (70 ng/μl) of purified C. burnetii DNA from the standard C. burnetii strain, as well as DNA in the different types of artificially contaminated samples at up to 0.007 ng/μl, indicating the high level of sensitivity of this assay. Earlier workers reported the detection of a concentration as low as 100 template (one cell) per sample in milk samples spiked with C. burnetii template DNA in decreasing amounts, from 106 to 10−2 particles per PCR mixture. In the cases in which low levels of C. burnetii particles were present in the milk, the assay could detect even a single C. burnetii particle in 1 ml of milk after the concentration of the template DNA by a factor of 200 with cetyltrimethylammonium bromide as the precipitation reagent (37).

Published reports on the detection of C. burnetii in cases of human spontaneous abortions are lacking. In pregnancy, infection has been associated with adverse outcomes; indeed, in one review of 15 patients who acquired infection during pregnancy, only 5 successfully gave birth and only two infants were of normal birth weight (30). These adverse outcomes are believed to occur through either placentitis or direct fetal infection (22). Langley et al. (18) reported seropositivity for C. burnetii in parturient women to be associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes.

Clinical samples from the patients that showed positivity in the trans-PCR and IFA were further screened by the qPCR for the quantification of the pathogen in the samples. The real-time PCR was found to be slightly more sensitive than the trans-PCR assay for the detection of C. burnetii.

The Sybr green-based real-time PCR targeting the IS1111a has been reported previously to be very specific and sensitive, with highly reproducible results, for the detection and quantification of the pathogen (15, 16). Among samples detected earlier to be positive for C. burnetii by the trans-PCR assay, the real-time PCR employed in this study found the highest numbers of DNA copies in placental tissues, followed by genital swabs, urine samples, and fecal swabs, from women with cases of spontaneous abortion. It has been estimated previously that 1 g of infected placental tissue can contain as many as one billion organisms (36).

C. burnetii phase I and phase II antibodies (IgG, IgM, and IgA) indicating acute and/or chronic infections in women (17) were detected by an IFA. The IFA has high specificity and sensitivity for phase II and phase I IgG antibodies and, to a lesser extent, also for the phase II and phase I IgM antibodies (31). The incidence of seropositivity for C. burnetii in the target group (25.68%) as determined by the IFA was lower than that reported previously for serum samples from humans with symptoms of Q fever, 76 and 86% for phase I and phase II antibodies, respectively (31). Another study found that 3.8% of parturient women with adverse pregnancy outcomes in areas where Q fever is endemic show antibodies to C. burnetii by the IFA (18). The finding that IgG class antibodies to phase I and phase II antigens of C. burnetii were detected in more serum samples than IgM and IgA antibodies in our study was similar to the previous results for the sera from humans with symptoms of Q fever (31).

The isolation of the pathogen from placental bits from four of five positive women in the present study was in concurrence with the findings in an earlier report on the recovery of the pathogen from 1 of 16 placental samples from women with spontaneous abortions that showed characteristic inclusions in tissue smears (27).

Three patients (patients 3, 12, and 13) were observed to be seropositive by the IFA but were found to be negative by both the PCR assays and pathogen isolation. The findings of our study concur with those in an earlier report (18), as no placental samples from 153 women determined to be seropositive by the IFA were found by PCR or culture to harbor C. burnetii.

The isolation method employed in the present study, with the detection of a total of 6.75% of the positive cases, turned out to be the least sensitive of the methods examined. Earlier workers reported that the isolation of the agent by cell culture is not completely satisfactory because of the lack of sensitivity of this method and that, therefore, this approach should be used only in special cases (13).

Our results suggested that it would be logical to screen patients with cases of spontaneous abortion for Q fever, preferably by the trans-PCR and/or real-time PCR assay, along with a serological test(s). This practice would help in detecting cases of Q fever in women, including those in women that shed the pathogen in their body fluids but give negative results in serological tests like an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (5) or IFA.

Placental tissue and genital secretions from infected woman are considered to be the principal sources of infection. In our study, of 16 women with spontaneous abortions that showed positivity in the trans-PCR assay as well as the real-time PCR assay, 3 shed C. burnetii in only one type of clinical sample, patient 2 in placental bits, patient 5 in urine, and patient 9 in genital secretions. Trans-PCR and real-time PCR assays employed in our study detected the pathogen in the feces and urine but not in the genital swab and placental bits from a woman that showed positivity in the IFA, which indicated that feces and urine should also be considered as potential sources of infection for humans via the inhalation of infectious aerosols or airborne dust.

Based on the results of the IFA, the overall prevalence of Q fever in women with spontaneous abortions turned out to be 25.68%. An earlier publication reported the seroprevalence of Q fever in human beings in India to be in the range from 2.7 to 26%, based on data from several studies (20).

In conclusion, the trans-PCR, real-time PCR, and IFA turned out to be better tests than pathogen isolation for the rapid and reliable diagnosis of Q fever in women with spontaneous abortions. Real-time PCR, with specificity equal to that of trans-PCR and slightly better sensitivity than trans-PCR, was found to be an excellent test for the detection and/or quantification of the pathogen in clinical samples. The IFA has the advantage of allowing the screening of a large number of serum samples. Among the samples of infected body fluids from women with spontaneous abortions, placental bits harbored the highest numbers of C. burnetii cells, followed by genital secretions and urine and fecal samples. The observed association of C. burnetii infection with reproductive disorders in humans and the high rate of excretion of the pathogen, particularly in the placenta, reveal that Q fever infection in humans remains underdiagnosed; the prevalence is underestimated and presents a potential public health threat.

Acknowledgments

We thank Rudolf Toman, head of the Institute of Virology, Slovak Republic, for kindly providing phenol-killed, purified, and lyophilized cells of the C. burnetii Nine Mile, phase I, strain (RSA 493) for this study. We thank all medical practitioners who shared the clinical samples for investigation.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 30 April 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arricau-Bouvery, N., and A. Rodalakis. 2005. Is Q fever an emerging or re-emerging zoonosis? Vet. Res. 36327-349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bellamy, R. J., and A. R. Freedman. 2001. Bioterrorism. QJM 94227-234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berri, M., K. Laroucau, and A. Rodolakis. 2000. The detection of Coxiella burnetii from ovine genital swabs, milk and fecal samples by the use of a single touchdown polymerase chain reaction. Vet. Microbiol. 72285-293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berri, M., A. Sourian, M. Crosby, D. Crochet, P. Lechopier, and A. Rodolakis. 2001. Relationships between the shedding of Coxiella burnetii, clinical signs and serological responses of 34 sheep. Vet. Rec. 148502-505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boulos, A., J. M. Rolain, M. Maurin, and D. Raoult. 2004. Measurement of the antibiotic susceptibility of Coxiella burnetii using real-time PCR. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 23169-174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brennan, R. E., and J. E. Samuel. 2003. Evaluation of Coxiella burnetii antibiotic susceptibilities by real-time PCR assay. J. Clin. Microbiol. 411869-1874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2002. Q fever—California, Georgia, Pennsylvania, and Tennessee, 2000-2001. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 51924-927. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cowley, R., F. Fernandez, W. Freemantle, and D. Rutter. 1992. Enzyme immunoassay for Q fever: comparison with complement fixation and immunofluorescence tests and dot immunoblotting. J. Clin. Microbiol. 302451-2455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cutler, S. J., G. A. Paiba, J. Howells, and K. L. Morgan. 2002. Q fever—a forgotten disease? Lancet Infect. Dis. 2717-718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fournier, P., and D. Raoult. 2003. Comparison of PCR and serology for the diagnosis of acute Q fever. J. Clin. Microbiol. 415094-5098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fournier, P. E., T. J. Marrie, and D. Raoult. 1998. Diagnosis of Q fever. J. Clin. Microbiol. 361823-1834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Franz, D. R., P. B. Jahrling, A. M. Friedlander, D. J. McClain, D. L. Hoover, W. R. Bryne, J. A. Pavlin, G. W. Christopher, and E. M. Eitzen, Jr. 1997. Clinical recognition and management of patients exposed to biological warfare agents. JAMA 278399-411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Henning, K., and R. Sting. 2002. Definitive ability of Stamp-staining, antigen-ELISA, PCR and cell culture for the detection of Coxiella burnetii. Berl. Munch. Tierarztl. Wochenschr. 115381-384. (In German.) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hoover, T. A., M. H. Vodkin, and J. C. Williams. 1992. A Coxiella burnetii repeated DNA element resembling a bacterial insertion sequence. J. Bacteriol. 1745540-5548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim, S. G., E. H. Kim, C. J. Lafferty, and E. Dubovi. 2005. Coxiella burnetii in bulk tank milk samples, United States. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 11619-621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Klee, S. R., J. Tyczka, H. Ellerbrok, T. Franz, S. Linke, G. Baljer, and B. Appel. 2006. Highly sensitive real-time PCR for specific detection and quantification of Coxiella burnetii. BMC Microbiol. 61186-1471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kovakova, E., J. Kazar, and A. Simkova. 1998. Clinical and serological analysis of a Q fever outbreak in western Slovakia with four-year follow-up. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 17867-869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Langley, J. M., T. J. Marrie, J. C. LeBlanc, A. Almudevar, L. Resch, and D. Raoult. 2003. Coxiella burnetii seropositivity in parturient women is associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 189228-232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lorenz, H., C. Jager, H. Willems, and G. Balger. 1998. PCR detection of Coxiella burnetii from different clinical specimens, especially bovine milk, on the basis of DNA preparation with silica matrix. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 644234-4237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Malik, S. V. S., and V. M. Vaidya. 2005. Q fever: a neglected zoonosis in India? p. 44-54. In Proceedings of the Third Annual Conference of Indian Association Veterinary Public Health Specialists and National Symposium. College of Veterinary Sciences, Punjab Agricultural University, Ludhiana, India.

- 21.Marmion, B. P., P. A. Storm, J. G. Ayres, L. Semendric, L. Mathews, W. Winslow, M. Turra, and R. J. Harris. 2005. Long-term persistence of Coxiella burnetii after acute primary Q fever. Q. J. Med. 987-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marrie, T. J. 1990. Acute Q fever, p. 125-160. In T. J. Marrie (ed.), Q fever: the disease, vol. 1. CRC Press Inc., Boca Raton, FL. [Google Scholar]

- 23.McQuiston, J. H., and J. E. Childs. 2002. Q fever in humans and animals in the United States. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2179-191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Norlander, L. 2000. Q fever epidemiology and pathogenesis. Microb. Infect. 2417-424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Norrung, B., M. Solve, M. Ovesen, and N. Skovgaard. 1991. Evaluation of an ELISA test for detection of Listeria spp. J. Food Prot. 54752-755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Office International des Epizooties. 2004. Q fever, part 2, section 2.2.2, chapter 2.2.10. In Manual of diagnostic tests and vaccines for terrestrial animals. Office International des Epizooties, Paris, France.

- 27.Peacock, M. G., R. N. Philip, J. C. Williams, and R. S. Faulkner. 1983. Serological evaluation of Q fever in humans: enhanced phase I titers of immunoglobins G and A are diagnostic for Q fever endocarditis. Infect. Immun. 411089-1098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Prasad, B., N. Chandiramani, and A. Wagle. 1986. Isolation of Coxiella burnetii from human sources. Int. J. Zoonoses 13112-117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Raoult, D. 1990. Host factors in the severity of Q fever. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 59033-38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schopf, K., D. Khaschabi, and T. Dackau. 1991. Enzootic abortion in a goat herd, caused by mixed infection with Coxiella burnetii and Chlamydia psittaci. Tierarztl. Prax. 19630-634. (In German.) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Setiyono, A., M. Ogawa, Y. Cai, S. Shiga, T. Kishimoto, and I. Kurane. 2005. New criteria for immunofluorescence assay for Q fever diagnosis in Japan. J. Clin. Microbiol. 435555-5559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Spyridaki, I., A. Gikas, D. Kofteridis, A. Psaroulaki, and Y. Tselentis. 1998. Q fever in the Greek island of Crete: detection, isolation and molecular identification of eight strains of Coxiella burnetii from clinical samples. J. Clin. Microbiol. 362063-2067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stemmler, M., and H. Meyer. 2002. Rapid and specific detection of C. burnetii by light cycler PCR, p. 149-154. In U. Reisch, C. Wittwer, and F. Cockerill (ed.), Methods and applications: microbiology and food analysis. Springer, Berlin, Germany.

- 34.Storz, J. 1990. Laboratory methods for rickettsiae and chlamydiae, p. 569-580. In G. R. Carter and J. R. Cole, Jr. (ed.), Diagnostic procedures in veterinary bacteriology and mycology, 5th ed. Academic Press, Inc., San Diego, CA.

- 35.Storz, J. 1990. Rickettsiae and chlamydiae, p. 309-331. In G. R. Carter and J. R. Cole, Jr. (ed.), Diagnostic procedures in veterinary bacteriology and mycology, 5th ed. Academic Press, Inc., San Diego, CA.

- 36.To, H., K. K. Htwe, N. Kako, H. Kim, T. Yamaguchi, H. Fukushi, and K. Hirai. 1998. Prevalence of Coxiella burnetii infection in dairy cattle with reproductive disorders. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 60859-861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Welsh, H. H., E. H. Lennette, F. R. Abhinanti, and J. F. Winn. 1958. Air-borne transmission of Q fever: the role of parturition in the generation of infective aerosols. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 70528-540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yoshiie, K., H. Oda, N. Nagano, and S. Matayoshi. 1991. Serological evidence that the Q fever agent (Coxiella burnetii) has spread widely among dairy cattle of Japan. Microbiol. Immunol. 35577-581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]