Abstract

An evaluation of anti-rubella virus immunoglobulin G (IgG) immunoassays that report in international units per milliliter (IU/ml) was performed to determine their analytical performance and the degree of correlation of the test results. A total of 321 samples were characterized based on results from a hemagglutination inhibition assay. The 48 negative and 273 positive samples were used to determine the sensitivity and specificity of the assays. When equivocal results were interpreted as reactive, the sensitivity of the immunoassays ranged from 98.9 to 99.9% and the specificity ranged from 77.1 to 95.8%. All assays had positive and negative delta values of less than 2. A significant difference between the mean results of all assays was demonstrated by analysis of variance. However, post hoc analysis showed there was good correlation in the mean results expressed in IU/ml between some of the assays. Our results show the level of standardization between anti-rubella virus IgG immunoassays reporting results expressed as IU/ml has improved since a previous study in 1992, but further improvement is required.

Rubella virus causes a relatively benign childhood rash and fever. However, primary maternal infection during the first trimester is associated with a 80 to 90% risk of congenital rubella syndrome (2, 3, 25). In developed countries, the risk of congenital rubella syndrome has been minimized through vaccination programs (22-24) and by testing pregnant women for evidence of rubella virus immunoglobulin G (IgG) at their first antenatal visit (10, 11). Since the isolation of rubella virus in 1962, rubella testing has developed continuously, with the hemagglutination inhibition (HAI) assay often being considered the reference method (4, 15, 29).

Since the 1980s, rubella virus IgG assays have been calibrated against the same World Health Organization (WHO) international standard rubella virus serum (second standard preparation) and test results have been reported in international units per milliliter (IU/ml). The introduction of quantitative measurement of rubella virus IgG had the potential to increase standardization and facilitate the comparison between the results of different tests.

In 1992, we published a multicenter evaluation comparing commercial immunoassays used to measure rubella virus IgG antibodies (9). The conclusion was that, although there was a moderate degree of correlation, reporting anti-rubella virus IgG levels in IU/ml had insufficient practical use. At that time, we concluded that the results of rubella virus antibody testing be confined to a statement concerning immunity rather than a numerical value. More than 15 years later, the assays compared in the 1992 study are no longer in common usage in Australia and have generally been replaced with random-access analyzers that perform a range of immunoassays of multiple disciplines. A comparison of six random-access and two microtiter plate (MTP) immunoassays that report anti-rubella virus IgG levels in IU/ml was undertaken to review analytical performance and determine whether the standardization of reporting in the newer assays had improved. While the standardization of reporting for rubella virus IgG levels is greater with the introduction of automated immunoassays, further improvement is needed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Samples.

A total of 321 serum or plasma samples were included in the study. The samples were from 201 plasma packs obtained from Australian blood donors and 83 serum samples from individuals presenting for routine pathology tests that were prescreened by the HAI assay and found to have low levels of rubella virus IgG. Another 28 sera from individuals with serological evidence of acute rubella infection were included in the study. They included 13 individual samples and 15 samples from three seroconversion panels. Nine sera containing anti-toxoplasma IgM antibodies were also tested.

Serum or plasma samples used in the study were collected and stored at −20°C. Samples were thawed and aliquoted into single-use vials that were refrozen and stored at −20°C until they were used. Before testing, thawed aliquots were held at 4°C for up to 3 weeks or until use and then were discarded. No sample underwent more than three freeze-thaw cycles.

Tests.

All samples were tested by the HAI assay and eight commercially available immunoassays. Selected samples were tested further using an in-house Western blot assay.

(i) HAI assay.

All samples were tested in an HAI assay (1, 13, 29). Briefly, samples were treated with kaolin to remove nonspecific agglutinins. A twofold serial dilution of each sample was made in phosphate-buffered saline buffer. Fresh pigeon red blood cells coated with rubella virus antigen obtained from Dade Behring (Marburg, Germany) were used as the indicator. The results were expressed as the reciprocal of the titer. Each sample was tested in duplicate, and the results were read by two independent readers. If a reading that exceeded a difference of 1 doubling dilution between duplicate tests or between readers was obtained, the sample was retested.

(ii) Immunoassays.

Six of the assays were automated immunoassays using random-access instruments that could perform a range of infectious disease and biochemical assays, and two were 96-well MTP immunoassays. All tests were performed as instructed by the manufacturer. The manufacturer's cutoff was applied to determine reactivity of the sample. All assays reported the test results in IU/ml.

The random-access immunoassays were Access Rubella IgG (Beckman Coulter, CA), AxSYM Rubella IgG (Abbott Diagnostics, IL), Advia Centaur Rubella G (Bayer HealthCare, NY), Immulite 2000 Rubella Quantitative IgG (Diagnostic Products Corporation, CA), Liaison Rubella IgG (DiaSorin, Saluggia, Italy), and Vidas Rub IgG II (bioMérieux, Marcy l'Etoile, France).

Access Rubella IgG (Beckman Coulter, CA) (Access) had rubella virus membrane antigen bound to paramagnetic particles. Anti-rubella virus IgG bound to the particles was detected using alkaline phosphatase-conjugated monoclonal antibody and a chemiluminescent substrate (Lumi-Phos). The light produced was proportional to the amount of bound patient anti-rubella virus IgG, and the results were calibrated against a multipoint calibration curve standardized against the WHO second international standard preparation for anti-rubella virus serum.

AxSYM Rubella IgG (Abbott Diagnostics, IL) (AxSYM) (8, 21) used a microparticle solid phase coated with rubella virus antigen. Anti-human rubella virus IgG bound to the solid phase was detected with an anti-human IgG conjugated to alkaline phosphatase and a 4-methylumbelliferyl phosphate substrate.

Advia Centaur Rubella G (Bayer HealthCare, NY) (Centaur) (6, 7, 17) employed a sandwich immunoassay using direct chemiluminometric technology. An anti-human IgG monoclonal antibody was coupled to paramagnetic particles acting as the solid phase. Rubella virus was labeled with acridinium ester. The test sample was simultaneously incubated with the solid phase and labeled rubella virus, and the resulting antibody-antigen complex was detected through the addition of acid and base reagents.

Immulite 2000 Rubella Quantitative IgG (Diagnostic Products Corporation, CA) (Immulite) (8, 20, 30) used beads coated with inactivated rubella virus as the solid phase and alkaline phosphatase conjugated to monoclonal murine anti-human IgG as the conjugate. Chemiluminescent substrate was used to detect the antibody-antigen reaction.

Liaison Rubella IgG (DiaSorin Saluggia, Italy) (Liaison) (21) had rubella virus antigen coated onto magnetic particles as the solid phase. The secondary antibody was a mouse monoclonal antibody linked to an isoluminol derivative. To detect bound anti-rubella virus IgG, a starter reagent was added and a flash chemiluminescence reaction was induced. The resulting light signal was measured using a photomultiplier and converted to relative light units that were proportional to the amount of anti-rubella virus IgG present in the sample.

Vidas Rub IgG II (bioMérieux, Marcy l'Etoile, France) (Vidas) (21, 30) combined a two-step sandwich immunoassay method using a fluorescence detection system. The solid-phase receptacle acted as both the solid phase and pipetting device. The conjugate was an alkaline phosphatase-labeled monoclonal anti-human IgG (mouse), and the substrate was 4-methylumbelliferyl phosphate.

The two MTP immunoassays used 96-well plates coated with rubella virus antigen and a series of standards to calibrate the assay. They were ETI-RUBEK-G Plus (DiaSorin, Saluggia, Italy) and Enzygnost Anti-Rubella-Virus/IgG (Dade Behring, Marburg, Germany).

ETI-RUBEK-G Plus (DiaSorin, Saluggia, Italy) (DiaSorin) (9) was a MTP immunoassay using rubella virus coated to the MTP wells. Anti-rubella virus antibodies in the sample were bound to the rubella virus and were detected using a protein A conjugated to horseradish peroxidase tracer and a tetramethylbenzidine-hydrogen peroxide substrate, giving a color change that was proportional to the amount of anti-human IgG bound to the solid phase.

Enzygnost Anti-Rubella-Virus/IgG (Dade Behring, Marburg, Germany) (Enzygnost) was a MTP immunoassay consisting of duplicate test wells, one coated with rubella virus and the other control well coated with noninfected cell culture. The secondary antibody was a rabbit antibody conjugated with peroxidase. The antibody-antigen reaction was detected using a tetramethylbenzidine-hydrogen peroxide substrate. The optical density of the control well antigen was subtracted from that of the antigen-coated well for each sample to reduce the effect of nonspecific reactivity.

Western blot assay.

Samples that were negative by the HAI assay but had an equivocal or positive test result in one or more immunoassays were tested by Western blotting if sufficient sample remained. Western blots were performed by running rubella virus lysate on a nonreducing 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel, transferring the proteins to nitrocellulose, and probing for antibody in plasma samples that were diluted 1 in 100 in buffer (16, 31, 32).

Analysis. (i) Sensitivity and specificity.

The results of the HAI assay were used to assign a negative or positive status to the samples. An HAI titer of less than 8 was considered negative for anti-rubella virus immunoglobulin. A titer of 8 or more was considered positive (15). The analytical sensitivity and specificity of each immunoassay were estimated by comparing the immunoassay qualitative results with the sample's assigned positive or negative status. The sensitivity and specificity of the immunoassays were calculated twice, first interpreting equivocal results as negative and then as positive. The Western blot result did not change the status of any samples and did not affect the estimations of sensitivity or specificity.

(ii) Statistical analyses.

The results expressed as IU/ml were used in statistical analyses. Where an assay produced a result expressed as greater than the highest limit of the assay, the result was assigned a value of the limit level plus one. For example, if the assay's highest reportable result was 300 IU/ml, results greater than 300 IU/ml were assigned a value of 301 IU/ml prior to statistical analyses. The exception was results from Centaur, because the highest reportable result changed from 500 IU/ml to 175 IU/ml midway through the evaluation. All results greater than 175 IU/ml were converted to 176 IU/ml for statistical analysis for this assay.

For all immunoassays, the mean values of the results expressed in IU/ml were compared by analysis of variance, and Tamhane's T2 post hoc test using SPSS (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) version 15.0. A P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Positive and negative delta values were estimated for each immunoassay (5). The delta value is the distance the mean of the positive and negative populations of a data set is removed from the cutoff and is measured in standard deviations. To calculate the delta value, a cutoff of 10 IU/ml was used for each assay, with all results greater than or equal to 10 IU/ml being analyzed as positive. Results less than 10 IU/ml were analyzed as negative.

RESULTS

Of the 321 samples that were tested by the HAI assay, 48 samples had HAI results less than 8 and were considered to have a negative status for anti-rubella virus antibodies. The 273 samples with an HAI titer of 8 or greater were considered positive and consisted of 20 samples with a titer of 8, 27 samples with a titer of 16, 56 samples with a titer of 32, 63 samples with a titer of 64, 52 samples with a titer of 128, 28 samples with a titer of 256, 19 samples with a titer of 512, and 8 samples with a titer of 1,024 or greater. The sensitivity and specificity for each immunoassay were estimated twice, once interpreting equivocal results as positive and again interpreting equivocal results as negative ( Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Sensitivity and specificity of eight immunoassays testing 48 negative and 273 positive samples for anti-rubella virus IgGa

| Assay | Sensitivity (%) (95% confidence limits [%]) with equivocal results assigned as:

|

Specificity (%) (95% confidence limits [%]) with equivocal results assigned as:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative | Positive | Negative | Positive | |

| Access | 96.0 (92.7-97.9) | 99.3 (97.1-99.9) | 95.8 (84.6-99.3) | 91.7 (79.1-97.3) |

| AxSYM | 98.2 (95.5-99.3) | 99.3 (97.1-99.9) | 85.4 (71.6-93.5) | 77.1 (62.3-87.5) |

| Centaur | 99.3 (97.1-99.9) | 99.6 (97.7-99.9) | 93.8 (81.8-98.4) | 87.5 (74.1-94.8) |

| Enzygnost | 99.6 (97.7-99.9) | 99.6 (97.7-99.9) | 91.7 (79.1-97.3) | 85.4 (71.6-93.5) |

| Immulite | 99.3 (97.1-99.9) | 99.6 (97.7-99.9) | 91.7 (79.1-97.3) | 81.3 (66.9-90.6) |

| Liaison | 98.2 (95.5-99.3) | 98.9 (96.6-99.7) | 95.8 (84.6-99.3) | 91.7 (79.1-97.3) |

| DiaSorin | 98.9 (96.6-99.7) | 99.9 (98.3-99.9) | 87.5 (74.1-94.8) | 83.3 (69.2-92.0) |

| Vidas | 96.7 (93.6-98.4) | 99.6 (97.7-99.9) | 95.8 (84.6-99.3) | 95.8 (84.6-99.3) |

Positive and negative status was defined by HAI test results.

There were 48 negative samples tested in all eight immunoassays. When the immunoassay equivocal results were assigned a negative status, the specificity of the eight immunoassays ranged from 85.4 to 95.8%. Twenty-eight of the 48 negative samples were negative in all eight immunoassays. The results for the other 20 samples are presented in Table 2. A Western blot assay could not be performed on 6 of the 20 samples. Of the remaining 14 samples, 10 were negative and 4 were positive by Western blotting. All four Western blot-positive samples had a positive or equivocal test result in three or more immunoassays. One sample was positive in all eight immunoassays. Two of the six samples that were not tested by Western blotting had six or more positive or equivocal immunoassay test results. There were 14 samples that were reactive by either one or two immunoassay test results. Access, Centaur, Liaison, and Vidas gave negative results for all of these 14 samples, whereas Enzygnost, Immulite, DiaSorin, and AxSYM gave a positive or equivocal result for 1, 4, 5, and 7 of these samples, respectively.

TABLE 2.

Qualitative and quantitative anti-rubella virus IgG test results and corresponding Western blot test results of 20 samplesa

| Sample no. | Western blot resultb | Test resultc for immunoassay

|

|||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Access

|

AxSYM

|

Centaur

|

Enzygnost

|

Immulite

|

Liaison

|

DiaSorin

|

Vidas

|

||||||||||

| Qual. | Quant. (IU/ml) | Qual. | Quant. (IU/ml) | Qual. | Quant. (IU/ml) | Qual. | Quant. (IU/ml) | Qual. | Quant. (IU/ml) | Qual. | Quant. (IU/ml) | Qual. | Quant. (IU/ml) | Qual. | Quant. (IU/ml) | ||

| 352494 | NT | Negative | 7.9 | Negative | 3.1 | Negative | 2.6 | Equivocal | 6 | Equivocal | 9.1 | Negative | <5.0 | Negative | 8.8 | Negative | 7 |

| 352516 | NT | Negative | 2.3 | Negative | 0.2 | Negative | 0.2 | Negative | <4 | Equivocal | 6.5 | Negative | <5.0 | Negative | 5.9 | Negative | 0 |

| 352514 | NT | Negative | 1.5 | Equivocal | 5.3 | Negative | 0.2 | Negative | <4 | Negative | <5.0 | Negative | <5.0 | Negative | 2.3 | Negative | 1 |

| 351150 | NT | Negative | 6.7 | Negative | 4.9 | Negative | 0.0 | Negative | <4 | Positive | 10.8 | Negative | <5.0 | Negative | 3.5 | Negative | 4 |

| 351157 | NT | Equivocal | 11.6 | Positive | 16.8 | Equivocal | 8.2 | Positive | 17 | Positive | 13.0 | Equivocal | 9.6 | Negative | 8.4 | Negative | 9 |

| 352505 | NT | Positive | 18.6 | Positive | 14.6 | Positive | 41.6 | Positive | 25 | Positive | 20.3 | Negative | 5.4 | Positive | 25.9 | Positive | 24 |

| 352492 | Negative | Negative | 1.7 | Negative | 0.0 | Negative | 0.2 | Negative | <4 | Equivocal | 5.2 | Negative | <5.0 | Equivocal | 10.4 | Negative | 1 |

| 331811 | Negative | Negative | 0.6 | Equivocal | 7.1 | Negative | 0.3 | Negative | <4 | Negative | <5.0 | Negative | <5.0 | Equivocal | 9.2 | Negative | 1 |

| 331930 | Negative | Negative | 1.1 | Equivocal | 8.7 | Negative | 2.6 | Negative | <4 | Negative | <5.0 | Negative | <5.0 | Negative | 1.9 | Negative | 1 |

| 331443 | Negative | Negative | 1.4 | Positive | 23.5 | Negative | 0.3 | Negative | <4 | Negative | <5.0 | Negative | <5.0 | Negative | 0.6 | Negative | 1 |

| 331442 | Negative | Negative | 0.9 | Positive | 14.8 | Negative | 0.9 | Negative | <4 | Negative | <5.0 | Negative | <5.0 | Negative | 1.4 | Negative | 1 |

| 331479 | Negative | Negative | 1.1 | Positive | 15.6 | Negative | 0.6 | Negative | <4 | Negative | <5.0 | Negative | <5.0 | Negative | 3.1 | Negative | 4 |

| 329934 | Negative | Negative | 1.1 | Positive | 28.1 | Negative | 0.7 | Negative | <4 | Negative | <5.0 | Negative | <5.0 | Negative | 3.5 | Negative | 1 |

| 331590 | Negative | Negative | 1.4 | Negative | 1.5 | Negative | 0.3 | Negative | <4 | Negative | <5.0 | Negative | <5.0 | Positive | 20.8 | Negative | 0 |

| 349450 | Negative | Negative | 1.3 | Negative | 0.6 | Negative | 0.0 | Negative | <4 | Negative | <5.0 | Negative | <5.0 | Positive | 47.9 | Negative | 0 |

| 331812 | Negative | Negative | 1.1 | Negative | 0.7 | Negative | 0.4 | Negative | <4 | Negative | <5.0 | Negative | <5.0 | Positive | 108.7 | Negative | 0 |

| 349703 | Positive | Negative | 7.8 | Negative | 4.0 | Equivocal | 7.6 | Equivocal | 6 | Negative | <5.0 | Equivocal | 9.1 | Negative | 5.9 | Negative | 5 |

| 349418 | Positive | Equivocal | 10.9 | Negative | 2.9 | Positive | 17.9 | Equivocal | 4 | Equivocal | 8.7 | Positive | 25.8 | Positive | 16.5 | Negative | 7 |

| 331441 | Positive | Negative | 7.1 | Equivocal | 5.3 | Equivocal | 5.1 | Positive | 8 | Equivocal | 7.8 | Negative | <5.0 | Negative | 5.7 | Negative | 5 |

| 348611 | Positive | Positive | 25.6 | Positive | 28.0 | Positive | 81.7 | Positive | 31 | Positive | 31.3 | Positive | 45.9 | Positive | 35.8 | Positive | 35 |

The 20 samples were negative in an HAI assay that had at least one reactive test result when tested in eight anti-rubella virus IgG immunoassays as part of an evaluation of the analytical sensitivity of those assays.

NT, not tested.

Qualitative (Qual.) and quantitative (Quant.) test results are given for each immunoassay.

Of the 273 samples assigned a positive status, 255 were positive by all immunoassays. The other 18 positive samples were negative or equivocal in one or more immunoassays. When equivocal immunoassay results were considered positive, the assay's sensitivities ranged from 98.9 to 99.9%. Five samples were reactive in one immunoassay only, eight samples were reactive in two immunoassays, three samples were reactive in three immunoassays, and two samples were reactive in four immunoassays (Table 3). Of the 18 samples, six samples had an HAI titer of 8 or 16, four samples had a titer of 32, and one sample each had a titer of 128 and 256. No sample assigned a positive status was negative or equivocal in more than four immunoassays. No assay reported a negative result on more than 3 of the 18 samples.

TABLE 3.

Results of 18 HAI positive samples that tested negative or equivocal in one or more of eight rubella IgG immunoassays

| Sample no. | HAI test result | Resulta of immunoassay

|

|||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Access

|

AxSYM

|

Centaur

|

Enzygnost

|

Immulite

|

Liaison

|

DiaSorin

|

Vidas

|

||||||||||

| Qual. | Quant. (IU/ml) | Qual. | Quant. (IU/ml) | Qual. | Quant. (IU/ml) | Qual. | Quant. (IU/ml) | Qual. | Quant. (IU/ml) | Qual. | Quant. (IU/ml) | Qual. | Quant. (IU/ml) | Qual. | Quant. (IU/ml) | ||

| 352519 | 8 | Equivocal | 13.8 | Equivocal | 9.3 | Equivocal | 8.8 | Positive | 10 | Positive | 15.0 | Positive | 11.1 | Positive | 11.4 | Equivocal | 12 |

| 352498 | 16 | Equivocal | 11.2 | Equivocal | 6.8 | Positive | 15.0 | Positive | 7 | Positive | 10.9 | Equivocal | 9.8 | Positive | 12.5 | Equivocal | 11 |

| 349091 | 8 | Positive | 29.9 | Negative | 3.6 | Negative | 0.0 | Positive | 79 | Positive | 23.1 | Positive | 61.0 | Positive | 39.9 | Negative | 2 |

| 351148 | 16 | Positive | 15.1 | Positive | 16.4 | Positive | 16.3 | Positive | 11 | Positive | 10.7 | Negative | 8.1 | Equivocal | 10.8 | Equivocal | 12 |

| 331447 | 32 | Equivocal | 13.6 | Positive | 23.7 | Positive | 16.8 | Positive | 11 | Positive | 13.6 | Equivocal | 10.1 | Equivocal | 10.6 | Positive | 16 |

| 348632 | 8 | Equivocal | 13.6 | Positive | 16.7 | Positive | 39.4 | Positive | 16 | Positive | 17.5 | Positive | 21.1 | Positive | 20.9 | Positive | 16 |

| 351149 | 32 | Positive | 19.9 | Positive | 65.4 | Positive | 24.5 | Positive | 27 | Positive | 20.3 | Negative | 6.3 | Positive | 19.2 | Positive | 17 |

| 349624 | 256 | Positive | 148 | Positive | 98.4 | Positive | 333.8 | Negative | <4 | Positive | 131.0 | Positive | 178.0 | Positive | 74.9 | Positive | 184 |

| 351164 | 32 | Equivocal | 14.7 | Positive | 35.8 | Positive | 37.5 | Positive | 23 | Positive | 74.4 | Positive | 15.2 | Positive | 19.7 | Positive | 20 |

| 349456 | 128 | Negative | 9.1 | Positive | 202.3 | Positive | >175.0 | Positive | 80 | Positive | 261.0 | Positive | 267.0 | Positive | 114.2 | Positive | 279 |

| 351176 | 16 | Positive | 18.7 | Positive | 30.4 | Positive | 29.7 | Positive | 25 | Positive | 14.1 | Negative | <5.0 | Positive | 20.1 | Equivocal | 13 |

| 351151 | 16 | Equivocal | 14.8 | Positive | 18.4 | Positive | 13.0 | Positive | 20 | Positive | 14.6 | Positive | 13.0 | Positive | 11.7 | Equivocal | 13 |

| 351107 | 32 | Equivocal | 12.5 | Positive | 13.1 | Positive | 16.6 | Positive | 25 | Equivocal | 6.9 | Positive | 41.2 | Positive | 20.9 | Positive | 31 |

| 351159 | 16 | Positive | 15.7 | Positive | 13.7 | Positive | 17.4 | Positive | 15 | Positive | 13.8 | Positive | 13.4 | Equivocal | 10.9 | Equivocal | 14 |

| 351153 | 16 | Equivocal | 11.4 | Positive | 15.4 | Positive | 143.1 | Positive | 11 | Negative | <5.0 | Positive | 14.1 | Positive | 11.9 | Positive | 19 |

| 348839 | 8 | Positive | 19.5 | Negative | 0.3 | Positive | 18.5 | Positive | 22 | Positive | 12.9 | Positive | 11.6 | Positive | 13.6 | Equivocal | 14 |

| 348566 | 8 | Negative | 9.4 | Equivocal | 6.9 | Positive | 11.4 | Positive | 8 | Positive | 13.1 | Positive | 12.6 | Positive | 14.7 | Positive | 19 |

| 349320 | 8 | Equivocal | 14.7 | Positive | 12.7 | Positive | 29.1 | Positive | 12 | Positive | 16.3 | Positive | 30.3 | Positive | 21.2 | Equivocal | 12 |

Qualitative (Qual.) and quantitative (Quant.) test results are given for each immunoassay.

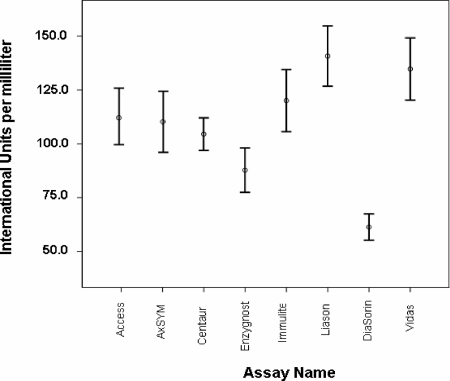

The mean of the results expressed in IU/ml of all eight immunoassays were significantly different (F = 8.375 with 7 df [P < 0.001]) (Fig. 1). Post hoc tests showed that the results of the DiaSorin assay were significantly different from the results from the other assays. The Access and AxSYM results demonstrated no significant difference compared to the results of all other assays, except DiaSorin. A significant difference between results of various combinations of the other assays was demonstrated (Table 4).

FIG. 1.

Mean and 95% confidence intervals of results reported for 321 samples tested with eight immunoassays for anti-rubella virus IgG tests giving results in international units per milliliter.

TABLE 4.

Tamhane's post hoc analysis of the means of anti-rubella virus IgG resultsa

| Immunoassay | Significance (P value)b of the difference of the means of immunoassays

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Access | AxSYM | Centaur | Enzygnost | Immulite | Liaison | DiaSorin | Vidas | |

| Access | ||||||||

| AxSYM | 1.000 | |||||||

| Centaur | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||||

| Enzygnost | 0.129 | 0.351 | 0.302 | |||||

| Immulite | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.892 | 0.013 | ||||

| Liaison | 0.127 | 0.092 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.797 | |||

| DiaSorin | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||

| Vidas | 0.591 | 0.469 | 0.010 | 0.000 | 0.998 | 1.000 | 0.000 | |

Anti-rubella virus IgG results were expressed as international units per milliliter from 321 samples tested on eight immunoassays.

Significance is defined as P < 0.05, and significant P values are indicated by bold font.

The negative and positive delta values were calculated for each immunoassay (Table 5). All assays had a delta value below 2, indicating that the mean of the negative and positive sample populations was less than 2 standard deviations removed from the cutoff of 10 IU/ml. DiaSorin had a negative delta value of less than 1, and AxSYM had a positive delta value of less than 1. The smaller the delta value, the greater the potential of false-positive or negative test results. However, the delta values may have been skewed because a number of test results were reported as greater or less than the limits of reporting for each assay.

TABLE 5.

Estimated delta values of 48 negative samples and 273 positive samples tested for the quantification of anti-rubella virus IgG in eight immunoassays

| Immunoassay | Estimated delta valuea

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Negative | Positive | |

| Access | −1.64 | 1.68 |

| AxSYM | −1.08 | 0.86 |

| Centaur | −1.83 | 1.71 |

| Enzygnost | −1.74 | 1.54 |

| Immulite | −1.47 | 1.27 |

| Liaison | −1.46 | 1.30 |

| DiaSorin | −0.62 | 1.79 |

| Vidas | −1.29 | 1.75 |

Estimated delta values expressed as standard deviations.

DISCUSSION

Testing samples for the presence of anti-rubella virus IgG to determine immune status is performed routinely, especially on women presenting for their first antenatal visit. For the past 15 years, most commercial immunoassays have been calibrated against a WHO international standard, and their results were reported in IU/ml, with 10 IU/ml generally considered the cutoff between immune and nonimmune status (14, 15, 26). In 1992, a multicenter evaluation of immunoassays reporting anti-rubella virus IgG results in IU/ml determined that only a moderate correlation between the results reported by each assay existed (9). Since this time, there have been few published investigations into anti-rubella virus IgG testing, even though many new assays have become available. The present study was undertaken to determine the performance characteristics of some new assays and to establish whether correlation between results reported in IU/ml had improved.

The status of all samples was assigned by HAI testing. Although HAI testing is often considered to be the reference method for rubella virus antibody detection, it must be noted that, unlike rubella virus IgG-specific immunoassays, HAI testing detects both IgG and IgM (13, 15). There were 28 samples from individuals known to have acute rubella infection included in the study, and all these samples were reactive by both the HAI test and immunoassays. Therefore, any discrepancy between the HAI test and immunoassays was not due to the detection of rubella virus IgM.

When a cutoff of 10 IU/ml was used, all assays included in the study had comparable sensitivity and specificity, with overlapping 95% confidence intervals. All assays reported some false-negative and false-positive test results. It is more acceptable to report a false-negative anti-rubella virus IgG test result than a false-positive result. Clinically, a false-negative result may give rise to unnecessary vaccination or, at worst, anxiety for a pregnant woman who has had contact with rubella. A false-positive result may lead to a susceptible person not being vaccinated and result in an infection if she is subsequently exposed to the virus. If a woman is in the first trimester of pregnancy, a congenitally acquired rubella infection may ensue.

When the equivocal test results were considered reactive, all assays had a sensitivity of 98.9% or greater, offering confidence in their ability to detect the presence of anti-rubella virus IgG. A relatively small percentage of false-negative results would be reported using any of the assays evaluated. However, the specificity of the assays would result in a higher percentage of false-positive results, with up to 22% false-positive results with AxSYM. The AxSYM specificity reported by Diepersloot et al. was 81.5% (8). In Australia, many laboratories use the manufacturer's cutoff to determine nonimmune status but apply a “gray zone” to express doubt over the levels of immunity conferred by low levels of reactivity. The “gray zone” used differs widely between laboratories.

Of the 48 samples with an HAI result of <8, four samples were subsequently found to be Western blot positive. Two samples had insufficient volume for Western blotting but were reactive in at least six of the eight immunoassays. It has been noted previously that using methods other than HAI testing, immune individuals with specific but low levels of rubella virus antibodies have been identified (12, 15, 18, 27, 28). Of the remaining 42 samples, Access, Centaur, Liaison, and Vidas reported no false-positive results; Enzygnost had one equivocal result (6 IU/ml). Immulite gave one positive test result (10.8 IU/ml) and three equivocal test results for the 42 samples. The application of a “gray zone” to these assays may not be necessary. AxSYM gave four positive and three equivocal results, the highest results being 28 IU/ml. This confirms previous findings which indicated about 1% of AxSYM positive results could not be confirmed (19). A “gray zone” of 30 IU/ml and a comment indicating doubt in immune status with results between 10 and 30 IU/ml may be considered for this assay. DiaSorin gave three positive test results (20.8, 47.9, and 108.7 IU/ml) and two equivocal test results. The spread of results overlapped considerably with the results reported for positive samples. An application of a “gray zone” to this assay would be impractical.

Statistical comparisons of the results reported by all eight immunoassays suggested that several assays gave comparable results. Results from the automated immunoassays Access, AxSYM, Centaur, and Immulite assays compared well, as did the Immulite, Liaison, and Vidas assays. Results from the MTP immunoassay DiaSorin (and, to a lesser extent Enzygost) did not compare well with any other assay. These results indicate that standardization of some anti-rubella virus IgG assays that report in IU/ml has occurred, but greater standardization throughout all immunoassays is required.

Positive and negative delta values were calculated for all immunoassays. The delta value describes the distance the mean of the positive and negative populations of a data set is removed from the cutoff and is measured in standard deviations. Therefore, an assay with a positive delta value of 4.0 has a mean of the results of positive samples 4 standard deviations from the cutoff. All immunoassays had a delta value of less than 2, implying poor separation of the negative and positive population, potentially leading to the false-negative and false-positive test results. Assays undergo variation from test event to test event, arising from changes of reagent batches, variation in the volume of reagents pipetted, temperature, length of incubation, and other process changes. A low delta value indicates an increased possibility of these variations in the test system affecting the sensitivity or specificity of the assay.

Immunoassays used for the quantification of rubella virus IgG are standardized to the WHO international standard rubella virus serum (second standard preparation) and report results in IU/ml. A report expressed in IU/ml implies traceability from one assay to another, much in the manner of many biochemistry assays. This and previous investigations indicate that the assumption of transferability of IU/ml is incorrect. Therefore, greater standardization of assays reporting rubella virus IgG in IU/ml is required.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the provision of assays at reduced or no charge by manufacturers and distributors. This study was funded by the Australian Government, Department of Health and Ageing, Diagnostics and Technology Branch, as part of “Quality Assurance Systems for Laboratories: Generalizing Their Use for Improving Pathology Services in Australia.”

Carlie Di Camilo and Sau-Wan Chan provided technical assistance.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 23 April 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anonymous. 1978. Haemagglutination-inhibition test for the detection of rubella antibody. J. Hyg. (London) 81373-382. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Best, J. M. 2007. Rubella. Semin. Fetal Neonatal Med. 12182-192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Best, J. M., S. O'Shea, G. Tipples, N. Davies, S. M. Al-Khusaiby, A. Krause, L. M. Hesketh, L. Jin, and G. Enders. 2002. Interpretation of rubella serology in pregnancy—pitfalls and problems. BMJ 325147-148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cradock-Watson, J. E. 1991. Laboratory diagnosis of rubella: past, present and future. Epidemiol. Infect. 1071-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Crofts, N., W. Maskill, and I. D. Gust. 1988. Evaluation of enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays: a method of data analysis. J. Virol. Methods 2251-59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dati, F. 2004. An update on laboratory productivity with infectious disease assays on the Bayer ADVIA Centaur immunoassay system. Clin. Lab. 5053-61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dati, F., G. Denoyel, and J. van Helden. 2004. European performance evaluations of the ADVIA Centaur infectious disease assays: requirements for performance evaluation according to the European directive on in vitro diagnostics. J. Clin. Virol. 30(Suppl. 1)S6-S10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Diepersloot, R. J., H. Dunnewold-Hoekstra, J. Kruit-Den Hollander, and F. Vlaspolder. 2001. Antenatal screening for hepatitis B and antibodies to Toxoplasma gondii and rubella virus: evaluation of two commercial immunoassay systems. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 8785-787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dimech, W., A. Bettoli, D. Eckert, B. Francis, J. Hamblin, T. Kerr, C. Ryan, and I. Skurrie. 1992. Multicenter evaluation of five commercial rubella virus immunoglobulin G kits which report in international units per milliliter. J. Clin. Microbiol. 30633-641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Francis, B. H., L. I. Hatherley, J. E. Walstab, and L. I. Taft. 1982. Rubella screening and vaccination programme at a Melbourne maternity hospital. A five-year review. Med. J. Aust. 1502-504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Francis, B. H., A. K. Thomas, and C. A. McCarty. 2003. The impact of rubella immunization on the serological status of women of childbearing age: a retrospective longitudinal study in Melbourne, Australia. Am. J. Public Health 931274-1276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kleeman, K. T., D. J. Kiefer, and S. P. Halbert. 1983. Rubella antibodies detected by several commercial immunoassays in hemagglutination inhibition-negative sera. J. Clin. Microbiol. 181131-1137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maroto Vela, M. C., M. C. Bernal Zamora, A. Levya Garcia, and G. Piedrola. 1986. Detection of specific IgG and IgM antibodies in the haemagglutination inhibition test and the enzyme-linked immunoassay for the diagnosis of rubella infection. Infection 14159-162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mitchell, L. A., M. K. Ho, J. E. Rogers, A. J. Tingle, R. G. Marusyk, J. M. Weber, P. Duclos, M. L. Tepper, M. Lacroix, and M. Zrein. 1996. Rubella reimmunization: comparative analysis of the immunoglobulin G response to rubella virus vaccine in previously seronegative and seropositive individuals. J. Clin. Microbiol. 342210-2218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. 1997. Detection and quantitation of rubella IgG antibody: evaluation and performance criteria for multiple component test products, specimen handling, and use of test products in the clinical laboratory; approved guideline. NCCLS guideline I/LA6-A, vol. 17, p.25. National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, Villanova, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nedeljkovic, J., T. Jovanovic, S. Mladjenovic, K. Hedman, N. Peitsaro, and C. Oker-Blom. 1999. Immunoblot analysis of natural and vaccine-induced IgG responses to rubella virus proteins expressed in insect cells. J. Clin. Virol. 14119-131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Okrongly, D. 2004. The ADVIA Centaur immunoassay system—designed for infectious disease testing. J. Clin. Virol. 30(Suppl. 1)S19-S22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.O'Shea, S., J. M. Best, and J. E. Banatvala. 1983. Viremia, virus excretion, and antibody responses after challenge in volunteers with low levels of antibody to rubella virus. J. Infect. Dis. 148639-647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.O'Shea, S., H. Dunn, S. Palmer, J. E. Banatvala, and J. M. Best. 1999. Automated rubella antibody screening: a cautionary tale. J. Med. Microbiol. 481047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Owen, W. E., T. B. Martins, C. M. Litwin, and W. L. Roberts. 2006. Performance characteristics of six IMMULITE 2000 TORCH assays. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 126900-905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Petersen, E., M. V. Borobio, E. Guy, O. Liesenfeld, V. Meroni, A. Naessens, E. Spranzi, and P. Thulliez. 2005. European multicenter study of the LIAISON automated diagnostic system for determination of Toxoplasma gondii-specific immunoglobulin G (IgG) and IgM and the IgG avidity index. J. Clin. Microbiol. 431570-1574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Plotkin, S. A. 2001. Rubella eradication. Vaccine 193311-3319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Robertson, S. E., S. L. Cochi, G. A. Bunn, D. L. Morse, and S. R. Preblud. 1987. Preventing rubella: assessing missed opportunities for immunization. Am. J. Public Health 771347-1349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Robertson, S. E., F. T. Cutts, R. Samuel, and J. L. Diaz-Ortega. 1997. Control of rubella and congenital rubella syndrome (CRS) in developing countries. Part 2. Vaccination against rubella. Bull. W. H. O. 7569-80. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Robertson, S. E., D. A. Featherstone, M. Gacic-Dobo, and B. S. Hersh. 2003. Rubella and congenital rubella syndrome: global update. Rev. Panam Salud Publica 14306-315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Skendzel, L. P. 1996. Rubella immunity. Defining the level of protective antibody. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 106170-174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Steece, R. S., M. S. Talley, M. R. Skeels, and G. A. Lanier. 1985. Comparison of enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, hemagglutination inhibition, and passive latex agglutination for determination of rubella immune status. J. Clin. Microbiol. 21140-142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Steece, R. S., M. S. Talley, M. R. Skeels, and G. A. Lanier. 1984. Problems in determining immune status in borderline specimens in an enzyme immunoassay for rubella immunoglobulin G antibody. J. Clin. Microbiol. 19923-925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.van Weemen, B., and J. Kacaki. 1976. A modified haemagglutination inhibition test for rubella antibodies, using standardized, freeze-dried reagents. Report of a comparative multi-centre trial. J. Hyg. (London) 7731-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vlaspolder, F., P. Singer, A. Smit, and R. J. Diepersloot. 2001. Comparison of Immulite with Vidas for detection of infection in a low-prevalence population of pregnant women in The Netherlands. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 8552-555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wilson, K. M., C. Di Camillo, L. Doughty, and E. M. Dax. 2006. Humoral immune response to primary rubella virus infection. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 13380-386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang, T., C. A. Mauracher, L. A. Mitchell, and A. J. Tingle. 1992. Detection of rubella virus-specific immunoglobulin G (IgG), IgM, and IgA antibodies by immunoblot assays. J. Clin. Microbiol. 30824-830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]