Abstract

All orthoretroviruses encode a single structural protein, Gag, which is necessary and sufficient for the assembly and budding of enveloped virus-like particles from the cell. The Gag proteins of Rous sarcoma virus (RSV) and human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) contain a short spacer peptide (SP or SP1, respectively) separating the capsid (CA) and nucleocapsid (NC) domains. SP or SP1 and the residues immediately upstream are known to be critical for proper assembly. Using mutagenesis and electron microscopy analysis of insect cells or chicken cells overexpressing RSV Gag, we defined the SP assembly domain to include the last 8 residues of CA, all 12 residues of SP, and the first 4 residues of NC. Five- or two-amino acid glycine-rich insertions or substitutions in this critical region uniformly resulted in the budding of abnormal, long tubular particles. The equivalent SP1-containing HIV-1 Gag sequence was unable to functionally replace the RSV sequence in supporting normal RSV spherical assembly. According to secondary structure predictions, RSV and HIV-1 SP/SP1 and adjoining residues may form an alpha helix, and what is likely the functionally equivalent sequence in murine leukemia virus Gag has been inferred by mutational analysis to form an amphipathic alpha helix. However, our alanine insertion mutagenesis did not provide evidence for an amphipathic helix in RSV Gag. Taken together, these results define a short assembly domain between the folded portions of CA and NC, which is essential for formation of the immature Gag shell.

In retroviruses the polyprotein Gag forms the protein shell of the immature virion. At the time of budding, maturation is triggered by proteolytic cleavage of Gag to yield the canonical MA (matrix), CA (capsid), and NC (nucleocapsid) proteins, with a concomitant change in morphology of the virus particle. For immature assembly of Gag virus-like particles (VLPs), the MA domain can be replaced by heterologous membrane binding domains (MBDs) (31, 59), and the NC domain can be replaced by leucine zipper interaction domains (2, 29, 73). By contrast, the CA portion of Gag is indispensable for properly formed immature particles. CA, which consists of two subdomains together with short immediately adjoining sequences, is responsible for the primary Gag-Gag interactions underlying the immature protein lattice (2, 37, 47, 67). For example, chimeric Gag proteins that share the same CA and adjacent sequences can coassemble into the same VLP even if the MA or NC domains are from different viruses (4, 41).

All immature retroviral particles have a similar appearance by thin-section transmission electron microscopy (TEM); they are spherical with an inner, electron-dense ring. The Gag lattice in immature particles is hexagonal (5, 6, 70), but the molecular contacts in the lattice have not been defined. In contrast, the hexagonal lattice of the shell of the mature virion core, which is composed of CA, is relatively well understood (15, 17, 18, 44, 49, 54). The CA N-terminal domain (CA-NTD) forms hexagonal rings, while the CA C-terminal domain (CA-CTD) forms bridges between these rings. The process by which proteolytic cleavage of Gag molecules in the immature Gag lattice leads to reorganization to create the mature CA lattice is not understood in molecular terms.

In the avian alpharetroviruses (e.g., Rous sarcoma virus [RSV]) and in lentiviruses (e.g., human immunodeficiency virus type 1 [HIV-1]), a short spacer peptide called SP (12 amino acid residues in RSV) or SP1 (14 residues in HIV-1) separates CA from NC in the Gag protein. For both RSV and HIV-1, SP and SP1 are predicted to form part of an α-helix that extends from near the end of CA through part or all of SP or SP1 (1, 45), and a number of genetic results support this prediction (1, 45, 51). Nevertheless, the last 11 amino acids of CA plus any included SP/SP1 sequences are disordered in all high-resolution structures of RSV and HIV-1 CA (10, 14, 34, 69). Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR)-based studies of polypeptide fragments encompassing SP or SP1 and the adjoining sequences offer conflicting conclusions about the likelihood that this region adopts an α-helical form in vivo (52, 55). The gammaretroviruses, including murine leukemia virus (MLV), do not contain any distinct SP domain but do contain a motif at the C terminus of CA that is similarly critical for assembly. Genetic data strongly suggest that this region forms an amphipathic α-helix in MLV (11).

SP1 or SP and the C-terminal residues of CA-CTD are critically important for proper assembly. Deletion of SP1 from HIV-1 Gag largely abrogates particle production in vivo (35, 46). In the baculovirus overexpression system and in vitro, deletion of SP1 results in the formation of tubular structures (20, 22, 53). The functions affected by mutations in the SP1 region are disputed but have been suggested to include Gag-Gag interaction (25, 46, 51, 61), Gag-nucleic acid interaction and RNA packaging specificity (26, 33, 61, 62), and Gag-membrane interaction (24, 25, 46). In RSV, deletions of and in SP grossly alter the sedimentation rate of released particles (36), presumably implying major morphological changes in virion structure. Insertion of a five-amino-acid sequence (GSGSG) between RSV SP and NC leads to budding of apparently flexible tubular particles in the baculovirus-insect cell expression system (29).

In addition to its role in immature assembly, SP/SP1 plays a critical role in virus maturation. SP/SP1 release from the C-terminal end of CA is the final proteolytic step in maturation. SP1 has been suggested to temporally regulate this cleavage step (57), and disruption of the cleavage site(s) between CA and SP/SP1 results in noninfectious particles that lack a properly formed mature core (56, 68, 71). The small-molecule inhibitor 3-O-(3′,3′-dimethylsuccinyl) betulinic acid (PA-457) specifically prevents this cleavage in HIV-1 (32, 42, 74, 75). Inhibition by PA-457 depends on the assembly state of Gag; PR-mediated cleavage of unassembled Gag is unaffected by the drug (42, 63). Additionally, the viral determinants of PA-457 activity and resistance mutants map to the CA/SP1 border region (3, 43, 74). Thus, the mechanism of PA-457 action has been inferred to involve direct interaction with the CA-SP1 cleavage site (63, 74).

EM analysis of RSV Gag mutants in the baculovirus overexpression system as well as in DF1 chicken cells has allowed us to define the sequence in this region that is important for proper immature assembly. Mutations in the last eight residues of CA, in all of SP, or in the first four residues of NC lead to extrusion of membrane-enclosed tubular Gag particles from cells. The equivalent SP1 sequence of HIV-1 cannot replace the RSV SP sequence.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Baculovirus constructs.

Plasmids were created using common subcloning techniques as well as two-step PCR mutagenesis and were propagated in Escherichia coli DH5α. Baculovirus constructs SP/NC(+8i) (where the insertion of GSGSG occurs after residue 8 of NC; other constructs contain the same insertion [i], incrementally moved four residues further upstream), SP/NC(+4i), SP/NC(−4i), SP/NC(−8i), CA/SP(0i) (insertion occurs at the CA/SP border), CA/SP(−4i), CA/SP(−8i), SP/NC(5s) (GSGSG occurs as a substitution, not an insertion), diglycine mutations GG1 to GG7, and alanine insertions 1 to 4 were constructed by two-step PCR mutagenesis using the vector pET-3xcΔMBDΔPR (9) as a template. A PstI-KpnI fragment from each PCR product was then inserted into the baculovirus vector pFB MA-CA (29), resulting in a reading frame expressing each mutant in a GagΔPR (Gag protein lacking the PR domain) background. RSV CA-SP1-NC 1 was created using two-step PCR as follows: RSV CA was amplified from pET-3xcΔMBDΔPR; the reverse primer used contained the SP1 sequence from HIV-1 strain HXB2, resulting in a product of RSV CA with HIV-1 SP1 appended. RSV NC was amplified from pET-3xcΔMBDΔPR using a modified forward primer containing a short length of HXB2 SP1 sequence. A second PCR using these two products as a mixed template joined the pieces, resulting in a fragment encoding RSV CA and NC linked by the 14-residue HIV-1 SP1 domain. A PstI-KpnI fragment from this product was then inserted into pFB MA-CA as above, resulting in RSV Gag containing the 14-residue HIV-1 SP1 sequence in place of the 12-residue sequence of RSV SP. RSV CA-SP1-NC2 and RSV CA-SP1-NC3 were engineered using the same method; in addition to SP1, RSV CA-SP1-NC2 also replaces the last eight residues of RSV CA and the first four residues of NC with HIV-1 sequence. RSV CA-SP1-NC3 replaces the last 11 residues of RSV CA and all of SP with the equivalent HIV-1 sequence. The Gag expression constructs were shuttled into baculovirus “bacmids” using the Bac-to-Bac Baculovirus Expression System (Invitrogen).

Retroviral vectors.

Constructs pQGagΔPR, pQGag+4iΔPR, and pQGag5sΔPR were derived from retroviral vector pQCXIP (Clontech) containing full-length RSV Gag. pQGagΔPR was created by removing the PR domain from Gag by PCR and reinserting the product into vector pQXCIP. pQGag+4iΔPR and pQGag+5sΔPR were constructed similarly but using two-step PCR mutagenesis to include the desired GSGSG mutation in the final product.

Cell culture and cell lines.

Baculovirus infections were performed with Spodoptera frugiperda Sf9 insect cells grown in SF-900 II serum-free medium (Gibco). Infectious baculovirus was obtained by transfection of 106 adherent Sf9 cells with 1 μg of bacmid DNA using CellFECTIN reagent (Invitrogen). Fresh Sf-900 II serum-free medium was placed onto the cells after 5 h, and baculovirus-containing medium was harvested 48 to 72 h later. This medium was clarified and then used to infect suspension cultures of fresh Sf9 cells, which were grown for 48 to 72 h before being assayed for Gag expression or prepared for EM analysis.

Chicken DF1 fibroblasts were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum, 5% Nuserum (Gibco), and 1% heat-inactivated chick serum. Avian cell lines were created by retroviral transduction using MLV vectors. pQGag constructs and a plasmid expressing vesicular stomatitis virus G protein were cotransfected into the Phoenix packaging cell line, which expresses MLV Gag-Pol, using FuGENE 6 reagent (Roche). Medium from the cells was used to infect naïve DF1 cells. One day after infection the DF1 cells were selected for 3 days in medium containing 1 μg/ml puromycin. The resistant cells were cultured, and expression of RSV Gag protein was confirmed by Western blotting.

EM.

Infected Sf9 cells were collected 48 h postinfection and fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde in Sorensen's NA-K buffer, pH 7.0. Samples were then postfixed in 2% osmium tetroxide and dehydrated in an increasing series of ethanol washes. TEM samples were then embedded in Spurr resin (65) (Electron Microscopy Sciences). Ultrathin sections 90 to 110 nm thick were cut from the embedded samples and mounted on copper grids. The grids were stained with 2% uranyl acetate and Reynold's lead citrate (60), and samples were viewed on a Phillips Morgagni 268 TEM. Scanning EM (SEM) samples were analyzed by correlative fluorescence microscopy-SEM as described previously (39). Briefly, DF1 cells grown on a coverslip etched with a finder grid were cotransfected with RSV Gag and dominant-negative fluorescently labeled VPS4 [VPS4(EQ)-green fluorescent protein (GFP)] (where EQ represents the mutation E228Q) plasmids at a 2:1 ratio using FuGENE 6 transfection reagent (Roche). Cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde at 24 h posttransfection and analyzed by fluorescence microscopy to identify cells expressing GFP. The locations of GFP-positive cells on the finder grid were noted. Samples were then postfixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde and dehydrated in ethanol as for TEM, critical-point dried, and coated with a thin film of evaporated carbon. The previously identified GFP-positive cells were then viewed on a Hitachi S4700 field emission SEM at the University of Missouri Electron Microscopy core facility.

RESULTS

Mutational analysis of the SP region.

Previous work showed that RSV GagΔPR assembled into spherical VLPs when expressed in Sf9 insect cells (30). In contrast, the insertion of a five-amino-acid residue linker (GSGSG) directly at the SP/NC border in Gag resulted in the assembly of flexible tubular structures on the surface of the cells (29). Another study in which SP was partially or wholly deleted revealed that the released particles in the medium had abnormal mobility on a velocity sedimentation gradient, implying an assembly defect, but particle morphology was not analyzed (36). In order to examine directly the importance of SP and the surrounding sequence during assembly, we have now created a series of mutations within the end of CA, SP, and the beginning of NC, utilizing the same GSGSG insertion described previously (Fig. 1). Mutation SP/NC(+8i) places the insertion after residue 8 of NC (D496). Each of the other constructs contains the same insertion, incrementally moved four residues further upstream, through NC, and finally to residue A468, which is eight amino acid residues upstream of the end of CA [mutation CA/SP(−8)]. Mutation SP/NC(0i) was previously described under the name MACA-fNC (29). A related construct, SP/NC(5s), places the GSGSG mutation at the SP/NC border as a substitution rather than an insertion, replacing residues 488MAVVN492. All of these mutant Gag proteins, along with wild-type (WT) RSV Gag and Gag lacking NC (MA-CA), were expressed in Sf9 insect cells using a baculovirus vector. The WT Gag and all of the mutant constructs described here lack the PR domain, due to its previously described inhibitory effect on assembly in this system (30).

FIG. 1.

Schematic diagram of mutations. All constructs are based on GagΔPR, an RSV Gag protein with a deletion of the PR domain. aa, amino acid.

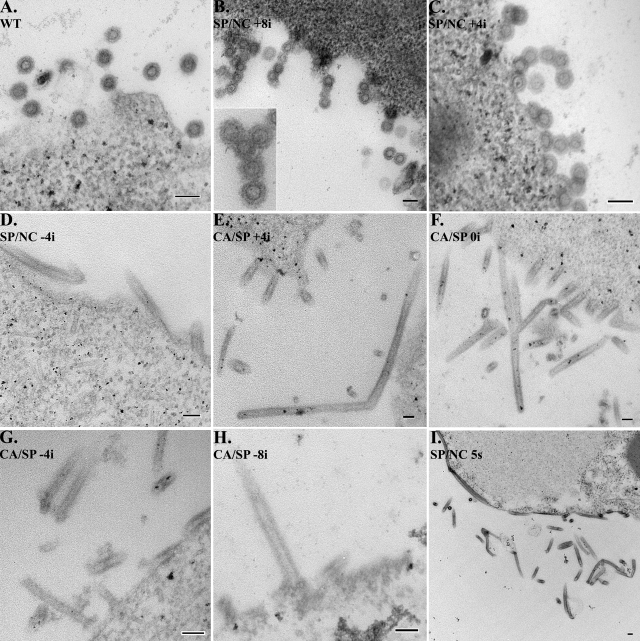

Upon analysis by TEM of thin-sectioned cells, we found that WT RSV Gag assembled into classical immature particles, as shown previously (4, 30). These particles had a discrete spherical outline at their boundaries and an electron-lucent center, surrounded by a distinct, stained-ring structure that presumably represents a portion of the Gag protein shell (Fig. 2A). The two mutants carrying a linker insertion within NC, SP/NC(+8i) and SP/NC(+4i), also formed spherical structures on the surface of infected cells (Fig. 2B and C). These particles were very close in appearance to WT RSV Gag VLPs, with the exception of the frequent appearance of chains of particles. At high magnification individual particles in the chain were observed to maintain a discrete visible inner ring and separate electron-lucent centers (Fig. 2B, inset), implying that each particle contained a distinct shell of Gag protein. We interpret these observations to mean that particles in a chain are either fused or adhered by the VLP membrane and not by the Gag shell.

FIG. 2.

Thin-section TEM of Gag-expressing insect cells. Sf9 insect cells expressing WT (A), SP/NC(+8i) (B), SP/NC(+4i) (C), SP/NC(−4i) (D), CA/SP(+4i) (E), CA/SP(0i) (F), CA/SP(−4i) (G), CA/SP(−8i) (H), and SP/NC(5s) (I) RSV GagΔPR were thin sectioned and analyzed for particle production. Scale bar, 100 nm.

In contrast, all other mutant Gag proteins with GSGSG mutations assembled into flexible tubes (Fig. 2D to I) that were indistinguishable from those observed in the original insertion CA/SP(0i) (29). The morphology was consistent whether the linker was inserted four amino acid residues from the end of SP in mutant SP/NC(−4i) (Fig. 2D), four residues from the beginning of SP in mutant SP/NC(−8i) (Fig. 2E), or at the CA/SP border in mutant CA/SP(0i) (Fig. 2F). To further delineate the sequence that is important for this dramatic morphology change, two additional GSGSG insertions were constructed in the C-terminal tail of CA. Mutants CA/SP(−4i) and CA/SP(−8i) also produced flexible tubes (Fig. 2G and H). Finally, to address the hypothesis that it is the spacing between the CA and NC domains that is important for proper assembly, we constructed a GSGSG substitution mutation, SP/NC(5s) (Fig. 1), in which the final residue of SP (M488) and first four residues of NC (A489 to N492) are replaced by GSGSG. This Gag mutant also resulted in tubular morphology (Fig. 2I). Taken together, these results imply that during the assembly of Gag at the membrane, the amino acid sequence surrounding and including SP forms a structure that is critical for proper immature spherical morphology.

Tubular assembly mutants fail to assemble in vitro.

In the presence of nucleic acid, purified RSV Gag protein expressed in E. coli can assemble into immature spherical particles that closely resemble the protein core of enveloped, PR-defective particles that have budded from cells (5, 72). Efficient assembly requires removal of the MBD of MA and the PR domain. We tested a subset of the GSGSG mutants in this in vitro assembly system for their ability to form proper immature particles (data not shown). The mutations were built into the protein ΔMBDΔPR, which was purified from E. coli lysates as described previously (47). By negative staining EM, SP/NC(+4i) formed spherical particles like those observed in parallel for the WT protein. By contrast, mutants SP/NC(5s) and SP/NC(−4i) consistently failed to assemble into any regular particles, with only irregular aggregates visualized on the EM grid. In vitro assembly has more stringent requirements than assembly in living cells, in that mutations in other parts of Gag lead to tubular assembly in cells while they abrogate assembly in vitro (58). Thus, the failure of these GSGSG insertion mutations to assemble in vitro further supports the existence of an essential assembly domain that ends in the first several residues of NC.

Defining the borders of the assembly element.

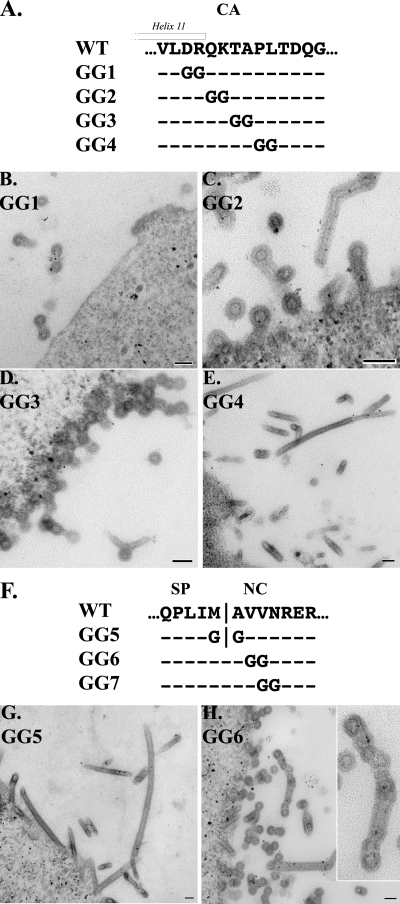

In order to delimit the morphology-determining element more precisely, we performed a more detailed mutational analysis on the end of the CA-CTD and the beginning of NC using adjacent diglycine (GG) substitutions (Fig. 3A and F). The mutant Gag proteins were expressed and imaged as above. Mutant GG1 replaces residues 463DR464. Despite the substitution of two charged residues within CA helix 11, GG1 assembled as spherical particles (Fig. 3B). Mutant GG2 replaces residues 465QK466, the final residue of CA helix 11 (Q465) and the first residue of the CA tail. This mutant gave an intermediate phenotype, forming a mixture of spherical and tubular structures (Fig. 3C). Mutant GG3, replacing residues 467TA468, produced particles with uniform spherical morphologies resembling the WT but with a tendency to form chains (Fig. 3D). Mutant GG4, replacing residues 469PL470, resulted in the assembly of flexible tubes like those observed for most of the other mutants (Fig. 3E). Since the mutations GG3 and GG4 flank the location of the insertion site in CA/SP(−8i), which assembled into tubes, these two diglycine substitutions define the N-terminal end of the morphology-determining element to be P469, although one or both of the residues Q465 and K466 may play a lesser role.

FIG. 3.

Fine-mapping of CA-SP-NC sequence element. Diglycine substitutions were created in RSV GagΔPR in the C-terminal tail of CA (A) or the N terminus of NC (F). Sf9 insect cells expressing protein GG1 (B), GG2 (C), GG3 (D), GG4 (E), GG5 (G), or GG6 (H) were thin sectioned and analyzed by TEM for particle morphology. The hollow line indicates helix 11 of CA. Scale bar, 100 nm.

Similarly, to identify which residues in the N terminus of NC are important for proper assembly, we created three GG substitutions that cover the first four residues of NC (Fig. 3F). Mutant GG5 lies directly on the SP/NC border, replacing the final residue of SP, M488, and the first residue of NC, A489. This Gag protein assembled into flexible tubes (Fig. 3G) similar to those observed for the GSGSG insertion and substitution mutants at the SP/NC border. Mutant GG6, replacing residues 490VV491 in NC, assembled into particles with a mixture of morphologies (Fig. 3H). Three categories of budding particles were observed: spheres, tubes, and intermediate structures. The last often displayed characteristics of both spheres and tubes, the most striking examples appearing as chains of incompletely formed particles. Unlike the chains formed by SP/NC(+8i) and SP/NC(+4i), the chains formed by GG6 included particles that did not have discrete electron-lucent centers closed by an electron-dense ring (Fig. 3H, inset). This result suggests that the Gag shell was incompletely formed, with adjacent particles sharing portions of their protein shell. Finally, mutant GG7, replacing residues 491VN492, assembled only into flexible tubes (data not shown). Thus, V491 and/or N492 has a role in spherical assembly. Since mutants GG6 and GG7 overlap at residue V491 but have a dramatic difference in morphology, V490 and V491 may play a less important role. Taken together, the data from GG substitutions near the SP/NC border imply that at least some of the first four residues of NC are important for proper immature assembly. This result was unexpected, as it was previously shown that replacing the entire NC domain of RSV with that of HIV-1 had no effect on particle morphology in the same baculovirus-insect cell expression system (4).

In summary, the combined data from the GSGSG and GG mutations suggest that the assembly element that is critical for proper immature assembly of RSV Gag comprises the 24 residues from P469 in the unstructured tail of CA through N492, the fourth residue of NC.

Mutagenesis to test for an amphipathic helix.

Structural information about SP and the C-terminal tail of CA is difficult to interpret in a unified manner. On the one hand, solved structures of retroviral CA domains that include this region, in whole or in part, assign it no secondary structure (10, 14, 34). Genetic studies in HIV-1 and MLV suggest that the region may form an α-helix (1, 11, 45). NMR analysis for HIV-1 offers conflicting conclusions on the existence of an α-helix (52, 55). Less is known about the corresponding segment of RSV Gag. The secondary structure prediction algorithm PSIpred predicts an α-helix spanning residues D472 to E494 (Fig. 4A), which matches rather well with our genetic data placing the assembly element within residues P469 to N492. All of the mutations presented above are rich in glycine, a helix-breaking residue, consistent with the hypothesis that helix formation is required during assembly of immature spherical VLPs.

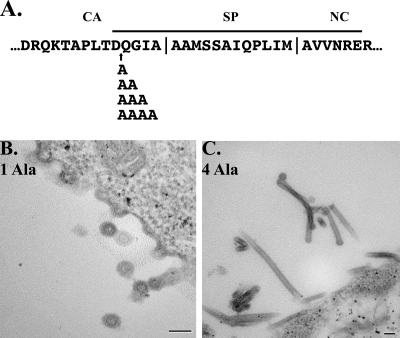

FIG. 4.

Alanine mutation of predicted α-helix. A series of alanine insertions was created within the predicted α-helix spanning CA-SP-NC of RSV Gag (bold line). Four insertions were made, consisting of one, two, three, or four alanine residues (A). Each protein was expressed in Sf9 insect cells, and budding particles were analyzed by thin-section TEM. Thin sections of Gag containing a single alanine (B) or four alanines (C) are shown. Scale bar, 100 nm.

Data from MLV suggest that the end of CA forms an amphipathic helix in which the correct helix phase, but not the number of helical turns, is critical (11). To address the hypothesis that in RSV a similar phased helix is required for proper assembly, we created a series of alanine insertion mutants between residues D472 and Q473 (Fig. 4A), the location of the GSGSG insertion in CA/SP(−4i), which gave rise to tubes (Fig. 2). Insertion of one or two Ala residues would alter the helical phase, while insertion of three or four alanines would approximately preserve the phase.

Gag proteins containing the alanine mutations were expressed in insect cells and analyzed by thin-section TEM as before. Insertion of one alanine residue did not have a dramatic effect on particle assembly (Fig. 4B), and the same phenotype was found for insertions of two or three alanines (data not shown). All three of these mutants budded predominantly spherical particles, similar in morphology to wild-type VLPs, and also exhibited the tendency to form particle chains as observed with several of the other sphere-forming mutants. In contrast, the Gag protein containing an insertion of four alanine residues assembled uniformly into flexible tubes (Fig. 4C). These results do not support the hypothesis that a phased α-helix in this region is required for proper Gag assembly. However, they do not eliminate the possibility of a different type of helical structure.

The equivalent HIV-1 sequence cannot functionally replace the RSV sequence.

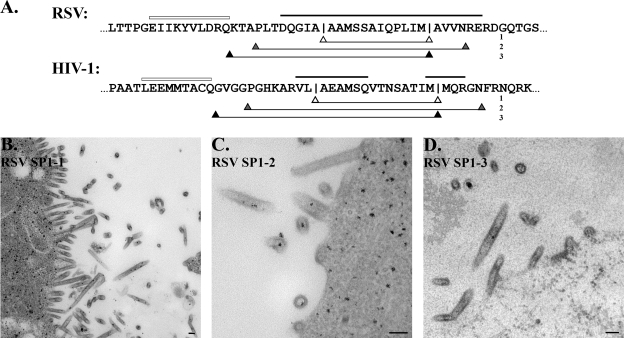

Like the avian alpharetroviruses, lentiviruses also contain a spacer peptide between CA and NC in Gag. The lengths and sequences of these peptides vary from 5 residues (equine infectious anemia virus) to 14 residues (HIV-1) to 20 residues (bovine immunodeficiency virus [BIV]), with little evident sequence similarity. According to structure predictions, a similar helical structure beginning in the tail of CA and extending into SP1 could be formed in HIV-1 Gag, except that in this case the predicted helix is split into two parts (Fig. 5A, bold lines). We decided to test for functional similarity by swapping the HIV-1 for the RSV sequence, thereby creating chimeric Gag proteins.

FIG. 5.

Substitution of HIV-1 sequence into RSV Gag. (A) Comparison of CA-SP-NC from RSV Gag with CA-SP1-NC from HIV-1 Gag reveals the predicted structural similarity. Hollow lines indicate helix 11 of CA, and bold lines designate predicted α-helices. Three sections of HIV-1 sequence were swapped into RSV GagΔPR, indicated by the open, shaded, and filled arrowhead lines (swaps are numbered at right). The RSV GagΔPR proteins containing HIV-1 sequence were then expressed in Sf9 insect cells, and budding particles were analyzed by thin-section TEM. (B) Swap 1. (C) Swap 2. (D) Swap 3. Scale bar, 100 nm.

We built three variations of chimeric proteins (Fig. 5A). The first, RSV SP1-1, replaces the 12-residue RSV SP with the 14-residue SP1 of HIV-1. The second, RSV SP1-2, replaces a longer sequence, residues P469 to V491, with HIV-1 residues P357 to N383, based on the results of our mutagenesis in RSV and NMR data on HIV-1 peptides (52). The third chimera, RSV SP1-3, replaces the entire tail of CA from the end of helix 11 and all of SP (K465 to M488) with the corresponding sequence from HIV-1, G353 to M378. The Gag chimeras were expressed in Sf9 insect cells and viewed by thin-section TEM as before. The results showed that none of the HIV-1 sequences was able to function in the context of RSV Gag. All three chimeras led to the assembly of flexible tubes (Fig. 5B to D). Occasionally, particles were observed that resembled normal spheres (Fig. 5C), but these were seen too infrequently to judge their significance. Taken together, these results suggest that despite predicted structural similarity, this region of RSV Gag performs a function during assembly that the HIV-1 sequence cannot. Of course, we cannot exclude the possibility that some different variation of the sequence exchange would lead to proper RSV assembly.

Expression of Gag mutants in avian cells.

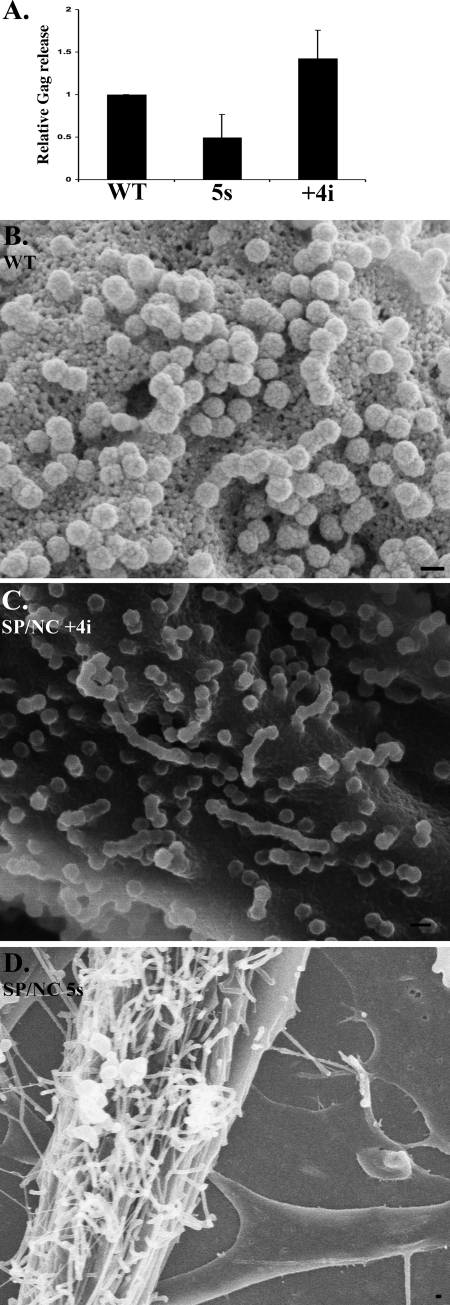

To confirm that the dramatic effect on assembly observed is not cell type dependent, we also examined the budding of a subset of the mutants in DF1 chicken fibroblasts, which support the replication of RSV. An MLV-based retroviral vector system was used to derive stable cell lines expressing mutant or WT RSV GagΔPR. Two representative Gag mutants first were chosen that had resulted either in tubes [SP/NC(5s)] or spheres [SP/NC(+4i)] in Sf9 cells. As analyzed by immunoblotting of cell lysates and of the VLP pellet collected by centrifugation from the medium, no significant differences in Gag expression or release were observed (Fig. 6A). The cells were also subjected to thin-section TEM, but no budding structures could be detected on the surface of any of the cell lines, probably due to a combination of low expression levels and the rapid budding that is a characteristic of alpharetroviruses in avian cells.

FIG. 6.

Analysis of budding in chicken cells. (A) DF1 cells stably expressing RSV GagΔPR WT, SP/NC(5s), or SP/NC(+4i) were analyzed for Gag release. Medium was collected over 24 h, and Gag release was quantified by Western blot analysis using α-RSV CA antibody. The amount of Gag released was normalized by expression level, with the WT set to 1, and relative release was plotted. Error bars indicate standard deviations from three independent experiments. Gag budding from DF1 cells was also analyzed for morphology. RSV GagΔPR WT (B), SP/NC(+4i) (C), or SP/NC(5s) (D) was cotransfected with VPS4(EQ)-GFP into DF1 cells. Fluorescently labeled cells were identified 48 h posttransfection and subsequently imaged by SEM to reveal the morphology of particles on the cell surface. Scale bar, 100 nm.

In order to visualize viral budding structures on cells, we turned to the technique of correlative fluorescence microscopy and SEM, coupled with coexpression of a protein that blocks the last step in budding. DF1 cells were cotransfected with a Gag expression plasmid and a plasmid expressing a fluorescently tagged dominant-negative form of VPS4 [VPS4(EQ)-GFP], which induces retrovirus budding arrest similar to the effect of a late domain mutation (19, 48, 50, 64). In this combined microscopic analysis, individual fluorescent cells are identified on a finder grid, and then after fixation the same cells are located and viewed by SEM. Cells expressing the control GagΔPR were largely covered with normal VLPs (Fig. 6B), as reported previously with this technique (39). Cells expressing SP/NC(+4i) in the same GagΔPR context also showed abundant spherical budding structures (Fig. 6C). By contrast, cells expressing SP/NC(5s) showed many flexible tubular structures on the plasma membrane (Fig. 6D). We interpret these tubes to be equivalent to the tubes visualized in Sf9 cells by thin-section TEM. Thus, tubular budding in the mutants appears to be an intrinsic property of Gag, independent of the cells in which it is expressed.

DISCUSSION

We have shown that the segment of RSV Gag comprising SP and closely adjoining sequences constitutes an assembly domain that plays a critical role in the formation of immature particles. Systematic mutagenesis coupled with EM defined this domain approximately as a 24-amino-acid sequence that includes the last 8 residues of CA, all 12 residues of SP, and the first 4 residues of NC. Glycine-rich mutations in this sequence uniformly led to tubular budding from cells and, for those mutants tested as purified proteins, to loss of assembly of any kind in vitro. Previous results from limited mutagenesis of RSV Gag implicate SP in the proper assembly and infectivity of virus particles (12, 29, 36). Several studies of the corresponding HIV-1 sequence also imply that SP1 and the C-terminal end of CA are important for virus budding and release (1, 45, 46, 51), and a similar function has been inferred for the BIV sequence (23). The Gag protein of the MLV, which lacks a cleaved SP between the CA and NC domains, also contains a sequence critical for particle assembly at the C terminus of CA (11). Together, these several studies suggest that an assembly domain between CA and NC is a universal feature of retroviral Gag proteins.

For HIV-1, mutations in and around SP have been interpreted to affect not only particle formation but also RNA genome packaging (26, 61) and Gag-membrane association (24, 25). Our working hypothesis to explain these diverse effects is that the SP assembly domain primarily mediates proper Gag-Gag interactions and that disruption of these interactions leads indirectly to other complex phenotypes because proper oligomerization is required for membrane association and for genome packaging. However, the possibility that SP or SP1 is more directly involved in membrane or RNA interaction is not excluded. For example, this sequence might position the NC domain to facilitate proper interactions with the genomic RNA.

What is the significance of tubular budding? The protein shell of mature retrovirus cores is made of CA protein. In HIV-1, this core is typically conical but also may be tubular. As purified mature proteins, HIV-1 CA (13, 16, 21, 44) and RSV CA (34) assemble into tubular structures, and in the case of HIV-1 these include conical structures that resemble authentic mature cores isolated from virions. The HIV-1 CA lattice was originally elucidated by cryo-EM reconstruction from CA tubes (44) and, more recently, at higher resolution from two-dimensional CA crystals (15, 17). The lattice is characterized by a hexagonal arrangement of the NTDs toward the outside, with the hexagonal units tied to each other by CTD-CTD contacts toward the inside. In addition, the lattice is stabilized by intermolecular CTD-NTD contacts (17, 37, 38). The mature lattice spacing, i.e., the center-to-center distance of the hexagons, is about 9.3 nm, and this is similar for in vitro assembled tubes and for authentic mature cores (7, 16, 44). Because of the ability of mature CA to form tubular structures, it is generally assumed that tubular morphology implies a mature lattice.

In contrast to CA, Gag proteins almost invariably assemble into spherical structures, as visualized most readily by in vitro assembly with purified proteins; the most widely studied are those of RSV (9, 47, 58, 72) and HIV-1 (8, 21, 22, 66). Although the exact nature of the Gag lattice remains to be deciphered, several of its properties have been defined. First, the CA portion of Gag, including the short, immediately adjoining sequences, is the major locus of the specific protein-protein interactions that underlie Gag assembly (4, 40, 41). Second, despite the central role of CA in assembly, for HIV-1 the immature Gag lattice spacing at ∼8.0 nm is smaller than the mature HIV-1 CA lattice spacing (5, 6), implying differences in the CA-CA domain contacts. One of these differences may be a domain swap of a portion of the CA-CTD (27, 28). Third, immature spherical assembly requires that the CA sequence be extended N terminally for at least a short stretch of amino acid residues; this leads to an unfolding of the N-terminal beta-hairpin of mature CA, a structure that is clamped in place by a salt bridge formed by the N-terminal Pro residue that is conserved in all orthoretroviruses. In HIV-1, it is unknown how unfolding of the beta-hairpin helps signal the CA domains to take on their immature protein-protein contacts, but monoclonal antibody studies suggest a pH-dependent conformational difference between the mature and the immature CA-NTDs (22). In RSV, the difference between mature and immature NTD contacts is better understood. The last 25 residues in each p10 domain just upstream of CA make a bridging contact to the neighboring NTD in the hexamer (58), precluding mature NTD contacts and yielding an immature hexamer with dimensions different from those of the mature hexamer.

Our findings that the sequences just downstream of CA, including SP, are critically important for spherical assembly suggest that this assembly domain acts as a molecular switch. This notion was originally suggested for HIV-1 by Gross et al. (22) because deletions of SP1 led to formation of tubes in the in vitro assembly system. The presence of the SP assembly domain is necessary but not sufficient for spherical, immature assembly since proteins with the structure CA-SP-NC in RSV or CA-SP1-NC in HIV-1 assemble readily into tubes (9, 22, 66). Thus, immature assembly apparently requires an “immature switch” both upstream and downstream of CA. If either is absent, the default is mature assembly. If both are present, Gag interactions result in the formation of the immature protein lattice. Removal of these switches by PR-mediated proteolysis leads to reassembly of CA to form the mature core. This model is supported not only by the fact that disrupting the function of SP prevents immature assembly but also by the finding that inhibiting removal of SP/SP1 from CA during maturation disrupts the formation of a proper mature core (35, 42, 43, 56, 57, 68, 71, 75).

How the SP assembly domain functions remains uncertain. A simple model suggested by Wright et al. (70) is based on their cryo-EM tomography of immature HIV-1 particles, which shows a density feature just below, i.e., internal to, the hole at the center of the hexagonal CA lattice. The authors modeled this density as a six-helix bundle comprising SP1 and perhaps adjoining sequences. This model is consistent with computer predictions of an alpha helix. But by definition a six-helix bundle would undergo only homotypic interactions, which would not readily explain our observation that the RSV SP assembly domain cannot be functionally replaced by the equivalent HIV-1 sequence. Similarly, it was reported previously that HIV-1 SP1 cannot replace the analogous sequence in the nonprimate lentivirus BIV (23). These findings suggest that the SP assembly domain makes specific contacts with not only itself but also other parts of Gag, most likely the CA-CTD. We hypothesize that the SP assembly domain interactions promote the formation of domain-swapped-CTD-CTD dimers, leading to a juxtaposition of one CTD to another that differs from the structure in the mature lattice, as experimentally observed by cryo-EM tomography for immature HIV-1 particles (70). Higher resolution tomography and more detailed mutagenesis will be needed to unravel the mechanism by which the SP assembly helps orchestrate Gag assembly.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by U.S. Public Health Service grants CA20081 to V.M.V. and AI73098 to M.C.J.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 30 April 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Accola, M. A., S. Hoglund, and H. G. Gottlinger. 1998. A putative alpha-helical structure which overlaps the capsid-p2 boundary in the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Gag precursor is crucial for viral particle assembly. J. Virol. 722072-2078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Accola, M. A., B. Strack, and H. G. Gottlinger. 2000. Efficient particle production by minimal Gag constructs which retain the carboxy-terminal domain of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 capsid-p2 and a late assembly domain. J. Virol. 745395-5402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adamson, C. S., S. D. Ablan, I. Boeras, R. Goila-Gaur, F. Soheilian, K. Nagashima, F. Li, K. Salzwedel, M. Sakalian, C. T. Wild, and E. O. Freed. 2006. In vitro resistance to the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 maturation inhibitor PA-457 (Bevirimat). J. Virol. 8010957-10971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ako-Adjei, D., M. C. Johnson, and V. M. Vogt. 2005. The retroviral capsid domain dictates virion size, morphology, and coassembly of Gag into virus-like particles. J. Virol. 7913463-13472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Briggs, J. A. G., M. C. Johnson, M. N. Simon, S. D. Fuller, and V. M. Vogt. 2006. Cryo-electron microscopy reveals conserved and divergent features of Gag packing in immature particles of Rous sarcoma virus and human immunodeficiency virus. J. Mol. Biol. 355157-168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Briggs, J. A. G., M. N. Simon, I. Gross, H. G. Krausslich, S. D. Fuller, V. M. Vogt, and M. C. Johnson. 2004. The stoichiometry of Gag protein in HIV-1. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 11672-675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Briggs, J. A. G., T. Wilk, R. Welker, H. G. Krausslich, and S. D. Fuller. 2003. Structural organization of authentic, mature HIV-1 virions and cores. EMBO J. 221707-1715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Campbell, S., R. J. Fisher, E. M. Towler, S. Fox, H. J. Issaq, T. Wolfe, L. R. Phillips, and A. Rein. 2001. Modulation of HIV-like particle assembly in vitro by inositol phosphates. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 9810875-10879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Campbell, S., and V. M. Vogt. 1997. In vitro assembly of virus-like particles with Rous sarcoma virus Gag deletion mutants: identification of the p10 domain as a morphological determinant in the formation of spherical particles. J. Virol. 714425-4435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Campos-Olivas, R., J. L. Newman, and M. F. Summers. 2000. Solution structure and dynamics of the Rous sarcoma virus capsid protein and comparison with capsid proteins of other retroviruses. J. Mol. Biol. 296633-649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cheslock, S. R., D. T. K. Poon, W. Fu, T. D. Rhodes, L. E. Henderson, K. Nagashima, C. F. McGrath, and W. S. Hu. 2003. Charged assembly helix motif in murine leukemia virus capsid: an important region for virus assembly and particle size determination. J. Virol. 777058-7066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Craven, R., A. E. Leure-DuPree, C. R. Erdie, C. B. Wilson, and J. W. Wills. 1993. Necessity of the spacer peptide between CA and NC in the Rous sarcoma virus Gag protein. J. Virol. 676246-6252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ehrlich, L. S., T. B. Liu, S. Scarlata, B. Chu, and C. A. Carter. 2001. HIV-1 capsid protein forms spherical (immature-like) and tubular (mature-like) particles in vitro: structure switching by pH-induced conformational changes. Biophys. J. 81586-594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gamble, T. R., S. H. Yoo, F. F. Vajdos, U. K. von Schwedler, D. K. Worthylake, H. Wang, J. P. McCutcheon, W. I. Sundquist, and C. P. Hill. 1997. Structure of the carboxyl-terminal dimerization domain of the HIV-1 capsid protein. Science 278849-853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ganser, B. K., A. Cheng, W. I. Sundquist, and M. Yeager. 2003. Three-dimensional structure of the M-MuLV CA protein on a lipid monolayer: a general model for retroviral capsid assembly. EMBO J. 222886-2892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ganser, B. K., S. Li, V. Y. Klishko, J. T. Finch, and W. I. Sundquist. 1999. Assembly and analysis of conical models for the HIV-1 core. Science 28380-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ganser-Pornillos, B. K., A. Cheng, and M. Yeager. 2007. Structure of full-length HIV-1 CA: a model for the mature capsid lattice. Cell 13170-79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ganser-Pornillos, B. K., U. K. von Schwedler, K. M. Stray, C. Aiken, and W. I. Sundquist. 2004. Assembly properties of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 CA protein. J. Virol. 782545-2552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Garrus, J. E., U. K. von Schwedler, O. W. Pornillos, S. G. Morham, K. H. Zavitz, H. E. Wang, D. A. Wettstein, K. M. Stray, M. Cote, R. L. Rich, D. G. Myszka, and W. I. Sundquist. 2001. Tsg101 and the vacuolar protein sorting pathway are essential for HIV-1 budding. Cell 10755-65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gay, B., J. Tournier, N. Chazal, C. Carriere, and P. Boulanger. 1998. Morphopoietic determinants of HIV-1 Gag particles assembled in baculovirus-infected cells. Virology 247160-169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gross, I., H. Hohenberg, and H. G. Krausslich. 1997. In vitro assembly properties of purified bacterially expressed capsid proteins of human immunodeficiency virus. Eur. J. Biochem. 249592-600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gross, I., H. Hohenberg, T. Wilk, K. Wiegers, M. Grattinger, B. Muller, S. Fuller, and H. G. Krausslich. 2000. A conformational switch controlling HIV-1 morphogenesis. EMBO J. 19103-113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guo, X. F., J. Hu, J. B. Whitney, R. S. Russell, and C. Liang. 2004. Important role for the CA-NC spacer region in the assembly of bovine immunodeficiency virus Gag protein. J. Virol. 78551-560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guo, X. F., and C. Liang. 2005. Opposing effects of the M368A point mutation and deletion of the SP1 region on membrane binding of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Gag. Virology 335232-241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guo, X. F., A. Roldan, J. Hu, M. A. Wainberg, and C. Liang. 2005. Mutation of the SP1 sequence impairs both multimerization and membrane-binding activities of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Gag. J. Virol. 791803-1812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guo, X. F., B. B. Roy, J. Hu, A. Roldan, M. A. Wainberg, and C. Liang. 2005. The R362A mutation at the C-terminus of CA inhibits packaging of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 RNA. Virology 343190-200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ivanov, D., J. R. Stone, J. L. Maki, T. Collins, and G. Wagner. 2005. Mammalian SCAN domain dimer is a domain-swapped homolog of the HIV capsid C-terminal domain. Mol. Cell 17137-143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ivanov, D., O. V. Tsodikov, J. Kasanov, T. Ellenberger, G. Wagner, and T. Collins. 2007. Domain-swapped dimerization of the HIV-1 capsid C-terminal domain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1044353-4358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Johnson, M. C., H. M. Scobie, Y. M. Ma, and V. M. Vogt. 2002. Nucleic acid-independent retrovirus assembly can be driven by dimerization. J. Virol. 7611177-11185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Johnson, M. C., H. M. Scobie, and V. M. Vogt. 2001. PR domain of Rous sarcoma virus Gag causes an assembly/budding defect in insect cells. J. Virol. 754407-4412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jouvenet, N., S. J. Neil, C. Bess, M. C. Johnson, C. A. Virgen, S. M. Simon, and P. D. Bieniasz. 2006. Plasma membrane is the site of productive HIV-1 particle assembly. PLoS Biol. 4e435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kanamoto, T., Y. Kashiwada, K. Kanbara, K. Gotoh, M. Yoshimori, T. Goto, K. Sano, and H. Nakashima. 2001. Anti-human immunodeficiency virus activity of YK-FH312 (a betulinic acid derivative), a novel compound blocking viral maturation. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 451225-1230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kaye, J. F., and A. M. L. Lever. 1998. Nonreciprocal packaging of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 and type 2 RNA: a possible role for the p2 domain of Gag in RNA encapsidation. J. Virol. 725877-5885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kingston, R. L., T. Fitzon-Ostendorp, E. Z. Eisenmesser, G. W. Schatz, V. M. Vogt, C. B. Post, and M. G. Rossmann. 2000. Structure and self-association of the Rous sarcoma virus capsid protein. Structure 8617-628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Krausslich, H. G., M. Facke, A. M. Heuser, J. Konvalinka, and H. Zentgraf. 1995. The spacer peptide between human immunodeficiency virus capsid and nucleocapsid proteins is essential for ordered assembly and viral infectivity. J. Virol. 693407-3419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Krishna, N. K., S. Campbell, V. M. Vogt, and J. W. Wills. 1998. Genetic determinants of Rous sarcoma virus particle size. J. Virol. 72564-577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lanman, J., T. T. Lam, S. Barnes, M. Sakalian, M. R. Emmett, A. G. Marshall, and P. E. Prevelige, Jr. 2003. Identification of novel interactions in HIV-1 capsid protein assembly by high-resolution mass spectrometry. J. Mol. Biol. 325759-772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lanman, J., T. T. Lam, M. R. Emmett, A. G. Marshall, M. Sakalian, and P. E. Prevelige, Jr. 2004. Key interactions in HIV-1 maturation identified by hydrogen-deuterium exchange. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol 11676-677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Larson, D. R., M. C. Johnson, W. W. Webb, and V. M. Vogt. 2005. Visualization of retrovirus budding with correlated light and electron microscopy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 10215453-15458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lee, S. K., V. Boyko, and W. S. Hu. 2007. Capsid is an important determinant for functional complementation of murine leukemia virus and spleen necrosis virus Gag proteins. Virology 360388-397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lee, S. K., K. Nagashima, and W. S. Hu. 2005. Cooperative effect of gag proteins p12 and capsid during early events of murine leukemia virus replication. J. Virol. 794159-4169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li, F., R. Goila-Gaur, K. Salzwedel, N. R. Kilgore, M. Reddick, C. Matallana, A. Castillo, D. Zoumplis, D. E. Martin, J. M. Orenstein, G. P. Allaway, E. O. Freed, and C. T. Wild. 2003. PA-457: a potent HIV inhibitor that disrupts core condensation by targeting a late step in Gag processing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 10013555-13560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li, F., D. Zoumplis, C. Matallana, N. R. Kilgore, M. Reddick, A. S. Yunus, C. S. Adamson, K. Salzwedel, D. E. Martin, G. P. Allaway, E. O. Freed, and C. T. Wild. 2006. Determinants of activity of the HIV-1 maturation inhibitor PA-457. Virology 356217-224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li, S., C. P. Hill, W. I. Sundquist, and J. T. Finch. 2000. Image reconstructions of helical assemblies of the HIV-1CA protein. Nature 407409-413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liang, C., J. Hu, R. S. Russell, A. Roldan, L. Kleiman, and M. A. Wainberg. 2002. Characterization of a putative alpha-helix across the capsid-SP1 boundary that is critical for the multimerization of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gag. J. Virol. 7611729-11737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liang, C., J. Hu, J. B. Whitney, L. Kleiman, and M. A. Wainberg. 2003. A structurally disordered region at the C terminus of capsid plays essential roles in multimerization and membrane binding of the Gag protein of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J. Virol. 771772-1783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ma, Y. M., and V. M. Vogt. 2004. Nucleic acid binding-induced gag dimerization in the assembly of Rous sarcoma virus particles in vitro. J. Virol. 7852-60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Martin-Serrano, J., T. Zang, and P. D. Bieniasz. 2003. Role of ESCRT-I in retroviral budding. J. Virol. 774794-4804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mayo, K., J. McDermott, and E. Barklis. 2002. Hexagonal organization of Moloney murine leukemia virus capsid proteins. Virology 29830-38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Medina, G., Y. Zhang, Y. Tang, E. Gottwein, M. L. Vana, F. Bouamr, J. Leis, and C. A. Carter. 2005. The functionally exchangeable L domains in RSV and HIV-1 Gag direct particle release through pathways linked by Tsg101. Traffic 6880-894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Melamed, D., M. Mark-Danieli, M. Kenan-Eichler, O. Kraus, A. Castiel, N. Laham, T. Pupko, F. Glaser, N. Ben-Tal, and E. Bacharach. 2004. The conserved carboxy terminus of the capsid domain of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Gag protein is important for virion assembly and release. J. Virol. 789675-9688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Morellet, N., S. Druillennec, C. Lenoir, S. Bouaziz, and B. P. Roques. 2005. Helical structure determined by NMR of the HIV-1 (345-392)Gag sequence, surrounding p2: implications for particle assembly and RNA packaging. Protein Sci. 14375-386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Morikawa, Y., D. J. Hockley, M. V. Nermut, and I. M. Jones. 2000. Roles of matrix, p2, and N-terminal myristoylation in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Gag assembly. J. Virol. 7416-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mortuza, G. B., L. F. Haire, A. Stevens, S. J. Smerdon, J. P. Stoye, and I. A. Taylor. 2004. High-resolution structure of a retroviral capsid hexameric amino-terminal domain. Nature 431481-485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Newman, J. L., E. W. Butcher, D. T. Patel, Y. Mikhaylenko, and M. F. Summers. 2004. Flexibility in the P2 domain of the HIV-1 Gag polyprotein. Protein Sci. 132101-2107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pepinsky, R. B., I. A. Papayannopoulos, E. P. C. Chow, N. K. Krishna, R. C. Craven, and V. M. Vogt. 1995. Differential proteolytic processing leads to multiple forms of the CA protein in avian-sarcoma and leukemia viruses. J. Virol. 696430-6438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pettit, S. C., M. D. Moody, R. S. Wehbie, A. H. Kaplan, P. V. Nantermet, C. A. Klein, and R. Swanstrom. 1994. The p2 domain of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Gag regulates sequential proteolytic processing and is required to produce fully infectious virions. J. Virol. 688017-8027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Phillips, J. M., P. S. Murray, D. Murray, and V. M. Vogt. 10 April 2008. A molecular switch required for retrovirus assembly participates in the hexagonal immature lattice. EMBO J. [Epub ahead of print.] doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 59.Reil, H., A. A. Bukovsky, H. R. Gelderblom, and H. G. Gottlinger. 1998. Efficient HIV-1 replication can occur in the absence of the viral matrix protein. EMBO J. 172699-2708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Reynolds, E. S. 1963. The use of lead citrate at high pH as an electron-opaque stain in electron microscopy. J. Cell Biol. 17208-212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Roldan, A., R. S. Russell, B. Marchand, M. Gotte, C. Liang, and M. A. Wainberg. 2004. In vitro identification and characterization of an early complex linking HIV-1 genomic RNA recognition and Pr55Gag multimerization. J. Biol. Chem. 27939886-39894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Russell, R. S., A. Roldan, M. Detorio, J. Hu, M. A. Wainberg, and C. Liang. 2003. Effects of a single amino acid substitution within the p2 region of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 on packaging of spliced viral RNA. J. Virol. 7712986-12995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sakalian, M., C. P. McMurtrey, F. J. Deeg, C. W. Maloy, F. Li, C. T. Wild, and K. Salzwedel. 2006. 3-O-(3′,3′-dimethysuccinyl) betulinic acid inhibits maturation of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Gag precursor assembled in vitro. J. Virol. 805716-5722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Shehu-Xhilaga, M., S. Ablan, D. G. Demirov, C. Chen, R. C. Montelaro, and E. O. Freed. 2004. Late domain-dependent inhibition of equine infectious anemia virus budding. J. Virol. 78724-732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Spurr, A. R. 1969. A low-viscosity epoxy resin embedding medium for electron microscopy. J. Ultrastruct. Res. 2631-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.von Schwedler, U. K., T. L. Stemmler, V. Y. Klishko, S. Li, K. H. Albertine, D. R. Davis, and W. I. Sundquist. 1998. Proteolytic refolding of the HIV-1 capsid protein amino-terminus facilitates viral core assembly. EMBO J. 171555-1568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.von Schwedler, U. K., K. M. Stray, J. E. Garrus, and W. I. Sundquist. 2003. Functional surfaces of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 capsid protein. J. Virol. 775439-5450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wiegers, K., G. Rutter, H. Kottler, U. Tessmer, H. Hohenberg, and H. G. Krausslich. 1998. Sequential steps in human immunodeficiency virus particle maturation revealed by alterations of individual Gag polyprotein cleavage sites. J. Virol. 722846-2854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Worthylake, D. K., H. Wang, S. H. Yoo, W. I. Sundquist, and C. P. Hill. 1999. Structures of the HIV-1 capsid protein dimerization domain at 2.6 angstrom resolution. Acta Crystallogr. D 5585-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wright, E. R., J. B. Schooler, H. J. Ding, C. Kieffer, C. Fillmore, W. I. Sundquist, and G. J. Jensen. 2007. Electron cryotomography of immature HIV-1 virions reveals the structure of the CA and SP1 Gag shells. EMBO J. 262218-2226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Xiang, Y., R. Thorick, M. L. Vana, R. Craven, and J. Leis. 2001. Proper processing of avian sarcoma/leukosis virus capsid proteins is required for infectivity. J. Virol. 756016-6021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yu, F., S. M. Joshi, Y. M. Ma, R. L. Kingston, M. N. Simon, and V. M. Vogt. 2001. Characterization of Rous sarcoma virus Gag particles assembled in vitro. J. Virol. 752753-2764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zhang, Y. Q., H. Y. Qian, Z. Love, and E. Barklis. 1998. Analysis of the assembly function of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Gag protein nucleocapsid domain. J. Virol. 721782-1789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zhou, J., L. Huang, D. L. Hachey, C. H. Chen, and C. Aiken. 2005. Inhibition of HIV-1 maturation via drug association with the viral Gag protein in immature HIV-1 particles. J. Biol. Chem. 28042149-42155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zhou, J., X. Yuan, D. Dismuke, B. M. Forshey, C. Lundquist, K. H. Lee, C. Aiken, and C. H. Chen. 2004. Small-molecule inhibition of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 replication by specific targeting of the final step of virion maturation. J. Virol. 78922-929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]