Abstract

The human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) Tat is a 14-kDa viral protein that acts as a potent transactivator by binding to the transactivation-responsive region, a structured RNA element located at the 5′ end of all HIV-1 transcripts. Tat transactivates viral gene expression by inducing the phosphorylation of the C-terminal domain of RNA polymerase II through several Tat-activated kinases and by recruiting chromatin-remodeling complexes and histone-modifying enzymes to the HIV-1 long terminal repeat. Histone acetyltransferases, including p300 and hGCN5, not only acetylate histones but also acetylate Tat at lysine positions 50 and 51 in the arginine-rich motif. Acetylated Tat at positions 50 and 51 interacts with a specialized protein module, the bromodomain, and recruits novel factors having this particular domain, such as P/CAF and SWI/SNF. In addition to having its effect on transcription, Tat has been shown to be involved in splicing. In this study, we demonstrate that Tat interacts with cyclin-dependent kinase 13 (CDK13) both in vivo and in vitro. We also found that CDK13 increases HIV-1 mRNA splicing and favors the production of the doubly spliced protein Nef. In addition, we demonstrate that CDK13 acts as a possible restriction factor, in that its overexpression decreases the production of the viral proteins Gag and Env and subsequently suppresses virus production. Using small interfering RNA against CDK13, we show that silencing of CDK13 leads to a significant increase in virus production. Finally, we demonstrate that CDK13 mediates its effect on splicing through the phosphorylation of ASF/SF2.

Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) is a complex retrovirus that depends on alternative splicing to generate mRNAs encoding viral proteins essential for viral replication. More than 40 different alternatively spliced HIV-1 mRNAs are produced through the differential combination of four 5′ splice donor sites (D1 to D4) and eight 3′ splice acceptor sites (A1, A2, A3, A4a, A4b, A4c, A5, and A7) (49, 51, 58). Splicing of HIV-1 mRNA generates three classes of RNA: unspliced (US) (9 kb), including Gag and polymerase; singly spliced (4 kb), including Env, Vpu, Vif, and Vpr; and doubly spliced (2 kb), including Tat, Rev, and Nef. The expression of these different viral mRNA species is temporally regulated. While multiply spliced viral RNA species are abundant during early stages of infection, US and singly spliced viral RNA appear at the later stages of infection (32, 33).

HIV-1 is highly dependent on the host splicing machinery in order to process viral transcripts into the different mRNA isoforms present in infected cells (reviewed in reference 59). Serine/arginine-rich (SR) proteins are among the splicing factors that are essential for the operation and regulation of viral and cellular splicing (29, 52). They belong to a family of a dozen different proteins characterized by one or two RNA recognition motifs at their N termini and an arginine/serine-rich (RS) motif at their C termini (12). SR proteins regulate splicing by recognizing exonic splicing enhancer elements (ESEs) embedded within exons and induce spliceosome assembly by stabilizing the interaction of snRNPs and/or other factors at the splice sites (56, 57). SR proteins are also thought to mediate cross-intron interactions between splicing factors bound to the 5′ and 3′ splice sites, namely, U1snRNP and U2AF (23, 60), and recruit splicing factors necessary for the subsequent formation of a cross-exon recognition complex (50).

The activities of SR proteins are regulated by phosphorylation of the RS domain. Although its precise physiological role is still unknown, the phosphorylation of SR proteins affects their protein-protein and protein-RNA interactions (61), intracellular localization and trafficking (9, 35), and alternative splicing of pre-mRNA (20). To date, several kinases have been reported to phosphorylate SR proteins, including SR protein kinase (SRPK)-family kinases (25, 37), mammalian pre-mRNA processing mutant 4 (PRP4) (36), a family of kinases termed Clk (Cdc2-like kinase) consisting of four members (Clk1 to -4) (15, 42), topoisomerase I (53), and Cdc2 kinase (44). Furthermore, several cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs) have been associated with splicing regulation by affecting SR protein phosphorylation. For example, CDK11p110 colocalizes with the general splicing factor RNPS1 and SR proteins, such as 9G8 (28). Other studies have also shown that CDK11, CDK12, and CDK13 are able to bind cyclin L and regulate alternative splicing in vitro (13, 14, 28).

We have previously shown that HIV-1 splicing is regulated by the viral protein Tat (5). Tat binds to the transactivation-responsive region, a secondary structure at the 5′ end of viral mRNA, and increases transcription elongation efficiency by recruiting CDK9 and other Tat-activated kinases (16, 63, 64). In addition, Tat transactivates viral gene expression by recruiting chromatin-remodeling complexes and histone-modifying enzymes, including histone acetyltransferases p300 and hGCN5 (2, 18, 31, 40, 41, 45, 48). Histone acetyltransferases not only acetylate histones but also acetylate Tat at lysine positions 50 and 51 in the arginine-rich motif (31, 45). According to our previous study, acetylated Tat (AcTat) inhibits HIV-1 splicing through its interaction with the splicing regulator p32. In two independent studies, p32 has been shown to inhibit splicing by inhibiting phosphorylation of ASF/SF2 (46) and to bind CDK13, a kinase involved in the regulation of splicing (14, 22). In this study, we demonstrated that AcTat interacts with CDK13 both in vivo and in vitro. We found that CDK13 regulates HIV-1 mRNA splicing and phosphorylates the splicing factor ASF/SF2. CDK13 was also shown to act as a restriction factor, in that its overexpression suppresses virus production. Using small interfering RNA against CDK13, we observed that silencing CDK13 leads to a significant increase in virus production. The model supported in this study is illustrated by the fact that AcTat interacts with p32 and CDK13 in a trimeric complex and inhibits HIV-1 splicing by affecting phosphorylation of the splicing factor ASF/SF2.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmids and drugs.

Flag-Tat plasmid was obtained from J. Hiscott (McGill, Montreal), glutathione S-transferase (GST)-p32 from J. Kjems (University of Aarhus, Denmark), and GST-SF2 from J. L. Manley (Columbia University, NY). pNLEnv was a kind gift from H. G. Kräusslich (Universität Heidelberg, Germany) (7). pNL50/51 was generated by subcloning the SalI-BamHI fragment from pNL4-3 (NIH Reagent Program) into a Bluescript SK+ vector (Stratagene) where lysines at positions 50 and 51 of Tat were mutated into alanines by use of a QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene). The following primers were used for mutagenesis: 5′-GGCATCTCCTATGGCAGGGCGGCGCGGAGACAGCGACG-3′ (forward) and 5′-CGT CGCTGTCTCCGCGCCGCCCTGCCATAGGAGATGCC-3′ (reverse). pcRev, GST-Tat, GST, and pNL-Luc vectors were provided by the NIH Reagent Program. The full-length CDK13 open reading frame (ORF) (pcCDK13) flanked with a hemagglutinin (HA) tag was cloned into pcDNA3 (22).

Cell culture and transfections.

HLM-1 cells (NIH Reagent Program) are HeLa-T4+ cells containing one integrated copy of the HIV-1 genome with a Tat-defective mutation at the first AUG of the Tat gene. HLM-1 and HeLa-T4+ cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, l-glutamine (2 mM), penicillin (100 U/ml)-streptomycin (100 μg/ml) (Quality Biological), and G418 (200 μg/ml) for selection. Five million HLM-1 or HeLa-T4+ cells were transfected with 5 to 10 μg of plasmid or small interfering RNA by nucleofection according to the manufacturer's protocol (Amaxa, Cologne, Germany). 293T cells were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, l-glutamine (2 mM), and penicillin (100 U/ml)-streptomycin (100 μg/ml). They were seeded in a six-well plate and transfected with pNLenv, Tat, and CDK13 expression plasmids by use of Metafectene according to the manufacturer's protocol (Biontex Laboratories GmbH, Martinsried, Germany).

GST pulldown assays.

GST-tagged proteins were purified as described previously (30). GST-p32, GST-Tat, and GST proteins were added to 2 mg of protein extracts from HeLa-T4+ cells and rotated overnight at 4°C. The next day, glutathione beads were added for 2 h and complexes were washed twice with TNE300 (100 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 300 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA) plus 1% NP-40 and once with TNE50 (100 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA) plus 0.1% NP-40. Proteins were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis on a 4 to 20% Tris-glycine gel (Invitrogen) and then transferred onto a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane, and immunoblotting was performed using anti-U1snRNP (Santa Cruz) and anti-CDK13 (anti-C-terminal peptide L49 and anti-C-terminal amino acids 1254 to 1312, respectively) or with anti-p32, kindly provided by A. M. Geneviere or W. Russell, respectively.

Coimmunoprecipitation and Western blotting.

Cells were centrifuged at 4°C and cell pellets were washed twice with Dulbecco's phosphate-buffered saline without calcium or magnesium. Whole-cell lysates were prepared as previously described (54). Ten-microgram portions of anti-Flag M1 (Sigma, F3040) or anti-HA probe (sc-7392) antibodies were incubated with 2 mg of whole-cell lysates overnight. The next day, protein A/G beads (30% slurry) were added for 2 h and then the immunoprecipitated (IPed) complex was washed twice with TNE300 plus 0.1% NP-40 and once with TNE150 (100 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA) plus 0.1% NP-40 and then resuspended in 2× SDS Laemmli buffer. Samples were separated on 4 to 20% or 6% Tris-glycine gels (Invitrogen) and transferred onto a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane, and anti-CDK13 antibody (Ab) was used for immunodetection.

Size exclusion chromatography.

293T cells were infected with adeno-Tat virus at a multiplicity of infection of 1 and incubated overnight as described previously (1). The cells in a 100-mm plate were lysed with 0.5 ml of whole-cell lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 0.5 M NaCl, 1% NP-40, 0.1% SDS) supplemented with protease cocktail (Sigma) and RNasin (Amersham). Cell lysates were clarified by centrifugation for 30 min at 10,000 × g, and then gel filtration was conducted on an Akta purifier system (Amersham Biosciences) with a Superose 6 10/30 column. One milliliter of 293T cells (protein concentration, 10 mg/ml) was applied to the column. Samples were eluted with buffer D (20 mM HEPES, pH 7.9, 0.05 M KCl, 0.2 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 0.05 M dithiothreitol [DTT], and 20% glycerol; Quality Biological, Inc.) plus 600 mM NaCl at a flow rate of 0.4 ml/min. Eluates were monitored by measuring absorbency at 280 nm. Fractions were collected in 0.5-ml volumes in individual tubes and then used for IP with Flag Ab or for immunoblotting with p32 and CDK13 antibodies.

RPA.

The probe for RNase protection assays (RPA) is expressed from pBS/HIV978-340, containing the major 5′ splice donor sequence of HIV-1 cut by HindIII (6). One microgram of purified DNA was used to generate the RNA probe in the presence of 32P-UTP by use of the T7 MAXIscript kit (Ambion, Austin, TX), which was then gel purified. RNA (30 μg) extracted from HLM-1 cells by use of RNA-Bee according to the manufacturer's directions (Tel-Test, Texas) was hybridized with a 5 × 105-cpm probe by use of the RPA III kit (Ambion). The hybridized RNA was digested with RNase T1 at a 1:100 dilution. Protected fragments were resolved on a 6% denaturing Tris-borate-EDTA-urea acrylamide gel and visualized by autoradiography.

Kinase assays.

Kinase assays were performed after immunoprecipitating CDK13 from 2 mg of HeLa cells transfected with HA-CDK13 by use of 10 μg of HA probe Ab (sc-7392). IPed complex was incubated with 1 μM ATP, 1 μCi of [γ-32P]ATP, and 1 μg of GST-SF2 or GST alone in TTK kinase buffer (43) containing 50 mM HEPES (pH 7.9), 10 mM MgCl2, 6 mM EGTA, and 2.5 mM DTT for 1 h at 37°C. Phosphorylated GST-SF2 was resolved on a 4 to 20% Tris-glycine gel, subjected to autoradiography, and quantified with a phosphorimager (Packard Instruments, Wellesley, MA). GST-SF2 and GST were expressed as described above and eluted from the glutathione beads with an elution buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8) and 5 mM glutathione.

Minigene splicing.

293T cells were transfected with pNLEnv, pcTat, pcTat50, pcTat51, and/or CDK13 expression plasmids. Cells were harvested after 48 h and protein extracts were analyzed by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and immunoblotting using antisera against HIV-1 Nef (1:1,000) and monoclonal Ab 902 directed against Env (1:500), both provided by the NIH Reagent Program.

RT assay.

Viral supernatants (10 μl) were incubated in a 96-well plate with reverse transcriptase (RT) reaction mixture containing 1× RT buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, 1 mM DTT, 5 mM MgCl2, 20 mM KCl), 0.1% Triton, poly(A) (10−2 U), poly(dT) (10−2 U), and [3H]TTP. The mixture was incubated overnight at 37°C, and 5 μl of the reaction mix was spotted on a DEAE Filtermat paper, washed four times with 5% Na2HPO4 and three times with water, and then dried completely. RT activity was measured in a Betaplate counter (Wallac, Gaithersburg, MD).

Single-cycle infectivity assays.

HeLa-CD4-long terminal repeat (LTR)/β-galactosidase (β-Gal) Magi indicator cells were plated in six-well plates (2 × 105 cells/well). HIV-1 virions (normalized to RT activity) were added in increasing dilutions to duplicate wells. At 48 h after infection, cells were harvested for quantitation of β-Gal production after hydrolysis of 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside (X-Gal) in vitro as previously described (11). Briefly, Magi cells infected with the virus express the β-Gal gene upon activation of the LTR with the viral Tat. X-Gal was added to cells, and subsequent cleavage of X-Gal by β-Gal-expressing cells confers a blue color to the infected cells as a marker of infection.

RESULTS

Tat acetylation mutant has reduced virus production.

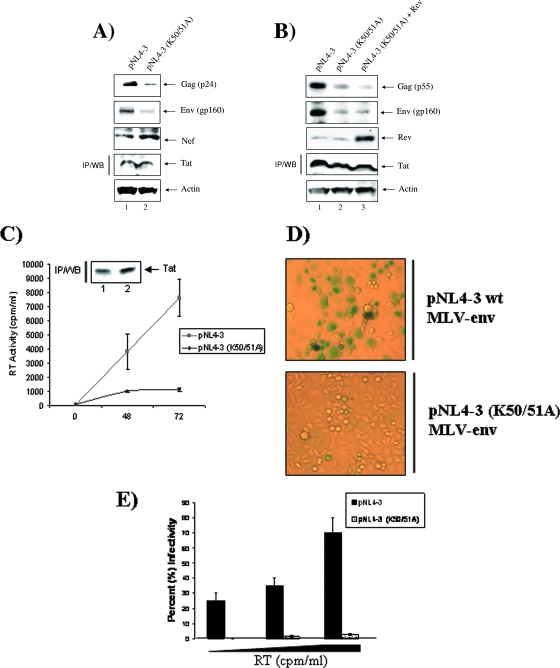

Posttranslational modifications are important determinants of Tat function. Acetylation is one of the most studied modifications of Tat and it is thought to enhance the function of Tat in transcriptional elongation (17, 45). In addition, we have demonstrated that when acetylated at lysines 50 and 51, Tat acquires a novel function, that of viral mRNA splicing regulation (5). In a previous study, we have established that AcTat interacts with the splicing inhibitor p32 in vitro and that both proteins colocalize in the nucleus and more specifically on the HIV-1 LTR. Mutating lysines 50 and 51 into alanines induces a change in HIV-1 splicing pattern by favoring the production of the spliced mRNA species (5). To determine the role of Tat acetylation at positions 50 and 51 in the context of the full virus, we cloned the pNL4-3 (K50, 51A) double mutant by changing lysines of Tat at positions 50 and 51 into alanines. As shown in Fig. 1A, transfection of 293T cells with the double mutant pNL4-3 (K50, 51A) produces low levels of US and singly spliced messages related to Gag (p24) and Env (gp160), respectively, compared to cells transfected with the wild-type (wt) virus, pNL4-3. In contrast, the levels of doubly spliced Nef seem to be high in cells transfected with the mutant virus compared to the wt virus. These results indicate that mutation of Tat at lysines 50 and 51 leads to a decrease in proteins encoded by US and singly spliced mRNA and an increase in protein encoded by doubly spliced mRNAs. Similar levels of Tat and actin were observed by IP/Western blotting and Western blotting, respectively. Decreases in Gag and Env were not due to a decrease in mRNA stability, as overexpression of Rev did not reverse the effect of the mutation on the production of the two corresponding genes (Fig. 1B). This decrease in the expression of structural proteins correlated with a decrease in the amount of virus produced by the mutant compared to the wt, as measured by RT activity in the supernatant after transfection of pNL4-3 and pNL4-3 (K50, 51A) (Fig. 1C). Again, similar amounts of Tat were seen from both wt and mutant clones after 72 h (Fig. 1C, inset). We also investigated whether the mutation affected the infectivity of the virus. To that end, we collected viral supernatant from cells transfected with pNL4-3 and pNL4-3 (K50, 51A), and infected Magi cells with different concentrations of the collected virus for 48 h. Cells were then fixed and stained with X-Gal and the number of β-Gal-expressing cells (blue cells) was counted. Percent infectivity was determined by calculating the percentage of blue cells among Magi cells. Figure 1D shows that NL4-3 (K50, 51A) lost its infectious potential, as indicated by the decrease in blue cells compared to what was seen for the NL4-3 virus. Increasing amounts of wt and mutant viruses, normalized to their RT activities, were used to infect Magi cells. Figure 1E indicates that increasing amounts of wt virus led to a significant increase in infectivity. However, the mutant virus had a reduced infectivity even when high amounts of virus were used for infection. While ∼70% of Magi cells were infected when NL4-3 was used at the highest virus concentration (6 × 105 RT activity), only ∼3% of Magi cells were infected with the mutant virus at a similar concentration (Fig. 1E), indicating that modifications at positions 50 and 51 of Tat are needed for the production of infectious virus.

FIG. 1.

Tat acetylation mutant has reduced virus production. (A and B) Western blotting (WB) to detect the different viral proteins by use of antibodies against Gag (1:200), Env (1:200), and Nef (1:1,000) in 293T cells transfected with pNL4-3 or pNL4-3 (K50, 51A) for 48 h in the absence (A) or presence (B) of Rev. (C) RT assay to determine virus production in supernatant of 293T cells transfected with pNL4-3 or pNL4-3 (K50, 51A) collected at 0, 48, and 72 h after transfection. The data are representative of three independent experiments. (Inset) Similar amounts of Tat were seen from both wt and mutant clones after 72 h. (D) Magi cell assay to determine infectivity of viruses harvested from 293T cells transfected with pNL4-3 or pNL4-3 (K50, 51A) collected 72 h after transfection. Magi cells were infected with the wt and mutant viruses. Blue cells are infected cells. (E) Infectivity was determined by calculating the percentage of infected cells (blue cells) in the Magi cell assay system after infection for 48 h with increasing amounts of virus and with increasing RT activity. The data are representative of three independent experiments.

CDK13 interacts with Tat in vitro and in vivo.

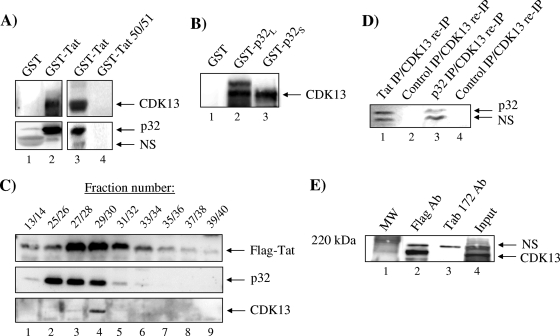

The recently identified CDK13 has been shown to interact with p32 and regulate the splicing of minigenes in vivo (14, 22). Based on our previous finding that AcTat interacts with p32, we wanted to determine whether Tat, p32, and CDK13 are part of the same complex. First, we performed a GST pulldown experiment by incubating GST-Tat with HeLa-T4+ cell extracts and showed by Western blotting that GST-Tat but not GST alone interacted with CDK13 (Fig. 2A, top). GST-Tat also interacted with p32 (Fig. 2A, bottom), showing that Tat interacts either directly or indirectly with both p32 and CDK13. Also, the GST-Tat mutant did not show binding to either CDK13 or p32 (Fig. 2A, lane 4). p32 is expressed in the cells in a long proform that can be proteolytically cleaved to produce the mature short p32 form (27). Both GST-p32 short and long forms interacted with CDK13 (Fig. 2B), indicating that Tat, p32, and CDK13 may be part of the same complex. We also found that GST-Tat interacted with a component of the spliceosome machinery, U1snRNP (data not shown). Second, we performed gel filtration chromatography to determine whether Tat, CDK13, and p32 comigrate into similar fractions. Extracts from 293T cells infected with adenovirus expressing Flag-Tat were separated using a size exclusion column into 50 fractions. Consecutive fractions were combined, Flag Ab was used to IP Flag-Tat, and anti-p32 was used to detect p32 by immunoblotting (Fig. 2C). Both Tat and p32 comigrated in fractions 25 to 30, i.e., in 6 out of 12 fractions where Tat was detected. Although Tat was present at high levels in fractions 31 to 34, p32 was mostly absent from these fractions, indicating that Tat was not always present in the same complex as p32. CDK13 comigrated with Tat and p32, as it was detected in fractions 27 and 28 at low levels and 29 and 30 at higher levels. We then performed IP/re-IP followed by Western blotting for p32. Fractions 27 to 31 (100 μl of each fraction) were pulled and IPed first with either anti-Tat (Fig. 2D, lane 1) or anti-p32 (Fig. 2D, lane 3), eluted with radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer, and then re-IPed with anti-CDK13 Ab. IPed complexes were then run on a gel and Western blotted for the presence of p32. Results in Fig. 2D indicate that these three proteins are complexed in vivo. The presence of this specific complex in these fractions was roughly 5% of the total Tat protein (data not shown). We further analyzed the association of Tat and CDK13 by immunoprecipitating Tat from HLM-1 cells transfected with Flag-Tat and determined its interaction with CDK13 by Western blotting. Indeed, after IP of Tat by use of a Flag Ab, we detected CDK13 binding by Western blotting in cells transfected with Flag-Tat (Fig. 2E).

FIG. 2.

CDK13 and Tat interact both in vitro and in vivo. (A) GST-Tat or GST (1 μg) was incubated in HeLa cell extract (1 mg) in order to pull down CDK13. Glutathione beads were added and then the precipitated complex was washed and separated on a 4 to 20% Tris-glycine polyacrylamide gel. Western blotting was then performed using CDK13 (1:1,000), p32 (1:1,000), and U1 70K (1:200) antibodies to determine whether these proteins were pulled down by GST-Tat. A control experiment utilized GST-Tat 50/51 (1 μg) (lane 3). (B) GST-p32 was used to determine whether p32 binds CDK13 under conditions similar to those described for panel A. (C) 293T cells lysated from the cells infected with adeno-Tat were fractionated using a Sepharose 6 chromatography column and analyzed with indicated antibodies by immunoblotting (p32 and CDK13) or IP (Flag). (D) IP followed by re-IP was done with pulled fractions of 27 to 31 (100 μl, ∼50 μg of protein) and anti-Tat (polyclonal immunoglobulin G [IgG]-purified Ab, 5 μg) (lane 1), preimmune IgG sera (5 μg) (lane 2), anti-p32 (∼1 μg) (lane 3), or IgG purified (1 μg) overnight with TNE50 plus 0.1% NP-40 (lane 4). The next day, samples were pulled down with protein A/G beads, washed with TNE150, and eluted with 50 μl of radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer. Eluates were re-IPed with CDK13 (∼1 μg) and Western blotted with anti-p32 Ab. (E) HLM-1 cells were transfected with Flag-Tat plasmid, and Flag Ab (5 μg) was used to pull down the Flag-Tat complex. Tab 172 was used as a negative control. Binding of CDK13 to Flag-Tat was determined by Western blotting for the IPed complex by use of an Ab against CDK13 (1:1,000). NS, nonspecific.

CDK13 increases HIV-1 splicing.

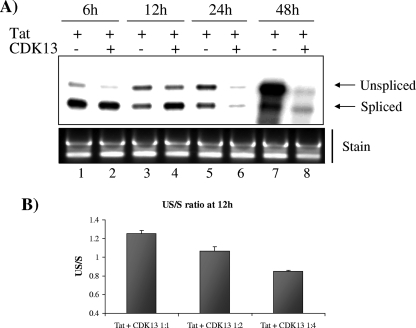

CDK13 was recently identified as a kinase that binds to cyclin L and regulates alternative splicing in vitro (14). Since we found that CDK13 interacts with Tat, we believe that CDK13 might be regulating HIV-1 mRNA splicing. To test this hypothesis, we studied the production of US and spliced HIV-1 mRNA after transfection of HLM-1 with Tat to induce transactivation, using a probe that can detect both US and spliced HIV-1 mRNA. Cells transfected with Tat alone or cotransfected with Tat and CDK13 were harvested at different time points after transfection, and the levels of US and spliced mRNA were assessed under each of these conditions. At 6 h after transfection, spliced mRNA was the predominant form of mRNA produced in cells expressing Tat alone or with CDK13 (Fig. 3A, lanes 1 and 2). US mRNA started accumulating at 12 h after transfection in cells overexpressing Tat alone and in the presence of CDK13 (Fig. 3A, lanes 3 and 4). After 24 and 48 h, the US mRNA became the predominant form of viral RNA in cells expressing Tat; however, viral mRNA production was dramatically decreased in cells cotransfected with Tat and CDK13 at the corresponding time points, indicating that the overexpression of CDK13 inhibited the production of the US RNA and subsequently led to the downregulation of viral expression (Fig. 3A, lanes 5, 6, 7, and 8). Since US mRNA started to accumulate 12 h after Tat transfection, we chose this time point to assess the dose-dependent effect of CDK13 on the accumulation of US mRNA by calculating the US/spliced (US/S) ratio. Figure 3B shows that increasing amounts of CDK13 decreased the US/S ratio in a dose-dependent manner, further indicating that CDK13 counteracts the accumulation of US mRNA needed for successful viral replication.

FIG. 3.

CDK13 regulates HIV-1 mRNA splicing. (A) Total RNA was extracted from HLM-1 cells transfected with Tat plasmids alone or cotransfected with Tat and CDK13 after 6, 12, 24, and 48 h and analyzed by RPA to detect the US and spliced HIV-1 mRNA. The free probe (312 nucleotides) and two protected fragments from US (262 nucleotides) and spliced (213 nucleotides) transcripts are indicated by arrows. Three micrograms of total RNA was run on a gel (1%) and stained with ethidium bromide. (B) US/S ratio calculated after quantification of the US and spliced viral mRNA detected by RPA from HLM-1 cells transfected with Tat plasmids (1 μg) with increasing amounts of CDK13 (1, 2, and 4 μg) for 12 h.

CDK13 regulates minigene splicing.

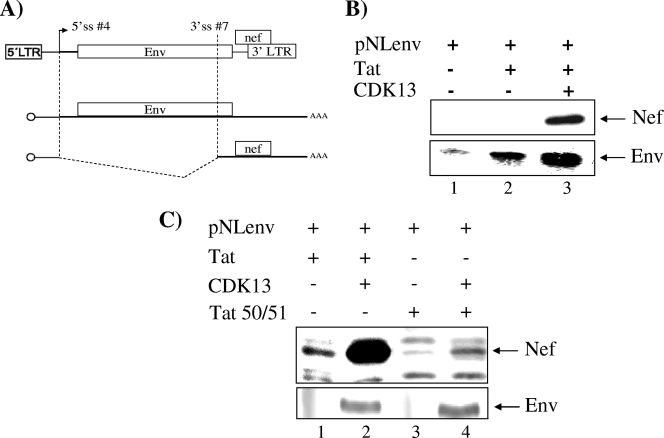

We then studied the effect of CDK13 overexpression on the splicing of pNLEnv (Fig. 4A). In this system, Env is expressed from a US mRNA and Nef from a spliced mRNA. 293T cells were cotransfected with pNLEnv along with Tat alone or Tat and CDK13 and the production of Nef and Env proteins was determined by Western blotting. Env protein production is increased when Tat is cotransfected with pNLEnv (Fig. 4B, compare lanes 1and 2), and no Nef was produced under these conditions. Interestingly, when CDK13 was cotransfected with Tat, Nef protein was produced, indicating that splicing can be detected under these conditions (Fig. 4B, lane 3). These results indicate that CDK13 induced splicing of the pNLEnv minigene. Cotransfection of CDK13 and the Tat (K50, 51A) mutant did not lead to an increase in Nef production, indicating that Tat acetylation at lysine 50 and 51 is needed for the CDK13-mediated effect on splicing (Fig. 4C).

FIG. 4.

CDK13 increases HIV-1 minigene splicing. (A) Schematic depiction of pNLenv. The vpu, env, and nef ORFs, 5′ splice site 4 (5′ ss #4) and 3′ splice site 7 (3′ ss #7), as well as the 5′ and 3′ LTRs, are represented in the top drawing. The middle and bottom drawings depict the US (middle) and spliced (bottom) RNA produced from pNLenv. (B) Western blotting to detect US Env and spliced Nef in HeLa cells transfected with pNLenv alone or with Tat in the presence or absence of CDK13 by use of anti-Env Ab (1:200) and anti-Nef Ab (1:1,000). Quantitation of lanes 1, 2, and 3 from Env Western blotting gave counts of 1.9 × 103, 8.3 × 103, and 26.5 × 103, respectively, while that of lanes 1, 2, and 3 from Nef gave counts of 0.3 × 103, 0.8 × 103, and 14.9 × 103, respectively. Therefore, the increase in Nef levels is ∼15-fold, whereas that for Env is ∼3.2-fold. (C) Nef and Env Western blots for 293 cells cotransfected with wt Tat or the Tat 50/51 mutant and CDK13.

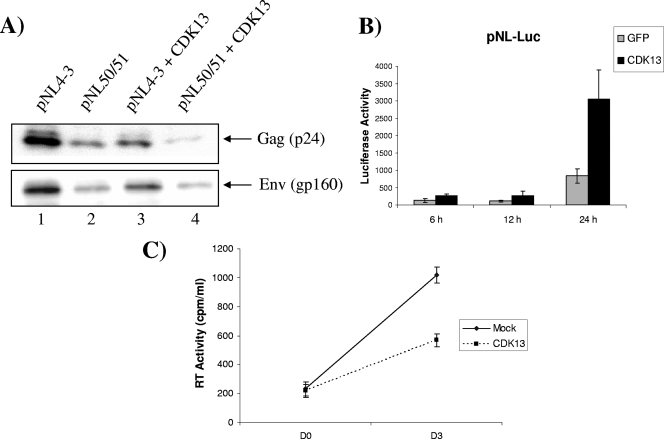

CDK13 may act as a restriction factor for viral replication.

Since our data from Fig. 3 showed that CDK13 overexpression dramatically decreased viral mRNA production 24 and 48 h after cotransfection with Tat, we wanted to determine whether the effect of CDK13 on viral mRNA is translated at the protein level. For this reason, we cotransfected the pNL4-3 wt or mutant with CDK13 and showed that CDK13 overexpression decreases the wt expression of Gag and Env to levels similar to those seen for the 50/51 mutant (Fig. 5A). However, to determine the effect of CDK13 on doubly spliced Nef, we cotransfected CDK13 with pNL-Luc, a pNL4-3 plasmid that has a firefly luciferase gene inserted into the nef gene. We monitored the luciferase expression at 6, 12, and 24 h after transfection of the plasmid with or without CDK13. Luciferase expression slightly increases over time in the absence of CDK13; however, the increase in luciferase activity was dramatic after 24 h of CDK13 cotransfection, indicating that CDK13 increases the production of doubly spliced Nef (Fig. 5B). The decrease in Gag and Env production upon overexpression of CDK13 leads to a 43% decrease in virus production, as determined by RT assay from a supernatant of cells transfected with pNL4-3 alone or cotransfected with CDK13 (Fig. 5C). Therefore, CDK13 not only affected the splicing ratio, as determined by our RNA splicing experiment, but also tipped the balance of the viral proteins produced toward the spliced Nef at the expense of US or singly spliced Gag and Env.

FIG. 5.

Effect of CDK13 overexpression on virus production. (A) 293T cells were transfected with pNL4-3 wt or the pNL4-3 (K50, 51A) mutant alone or cotransfected with CDK13 plasmid, and Western blotting was performed to determine the effect of CDK13 on the expression of viral proteins Gag, Env, and Nef. (B) pNL-Luc was cotransfected with green fluorescent protein (GFP) or CDK13 expression vectors. Luciferase activity was measured 6, 12, and 18 h after transfection. The data are representative of three independent experiments. (C) An RT assay was performed to measure virus secreted in cell supernatant collected immediately (D0) and at day 3 (D3) after cotransfecting 293T cells with pNL4-3 and empty vector (Mock) or CDK13. The data are representative of three independent experiments.

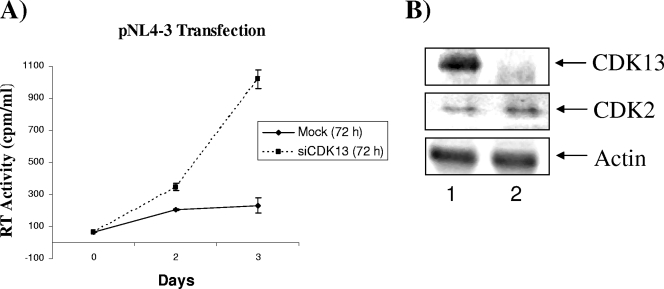

Silencing of CDK13 increases HIV-1 production.

Since our data suggest that CDK13 overexpression may restrict the virus, we wanted to determine whether CDK13 silencing increases virus production. HeLa-T4+ cells were transfected with siCDK13 or mock transfected for 72 h; cells were harvested, reseeded, and transfected with the pNL4-3 viral strain; and RT activity was measured at different days after transfection. In mock-transfected cells, RT activity slowly increased, while it increased dramatically in cells transfected with siCDK13, to a level whereby RT activity was ∼5 times higher in cells transfected with siCDK13 than mock-transfected cells at days 2 and 3 (Fig. 6). CDK13, but not CDK2 or actin, levels were decreased in siCDK13-treated cells (Fig. 6B). These results further demonstrate the restrictive role of CDK13 in viral replication and correlate CDK13 silencing to an increase in viral replication.

FIG. 6.

Effect of CDK13 silencing on virus production. HeLa cells were transfected with siCDK13 or with the small interfering enhanced green fluorescent protein gene (Mock) as a negative control for 72 h, and then cells were reseeded and transfected with pNL4-3. Viral supernatants (from three independent experiments) were collected at days 0, 2, and 3; RT activity was measured and is represented on the y axis as cpm/ml. (B) Western blotting of CDK13 and control proteins CDK2 and actin (25 μg of total protein) from HeLa cells transfected with siCDK13 after 72 h.

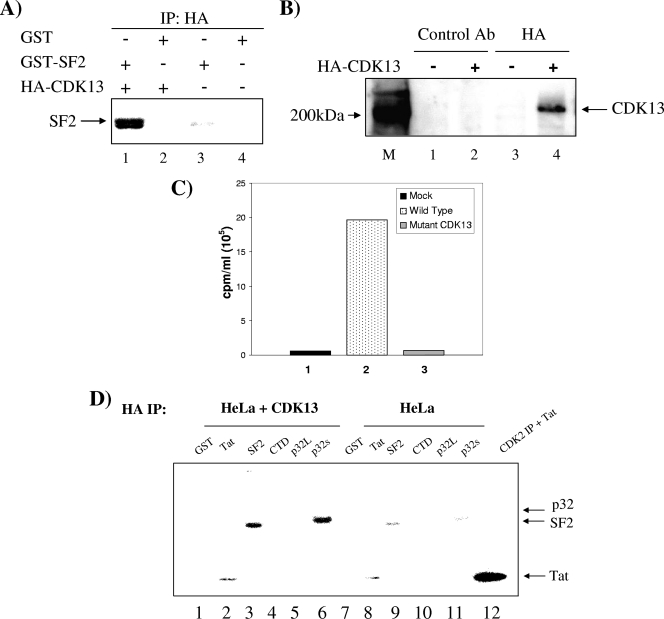

CDK13 regulates splicing by phosphorylating the splicing factor ASF/SF2.

CDK13 has been identified as a protein that binds tightly to the splicing regulator p32. So far, our data suggest that Tat, p32, and CDK13 may form one complex that acts to regulate HIV-1 mRNA splicing. The main study that has established a role for p32 in splicing demonstrated that p32 does so by inhibiting the phosphorylation of ASF/SF2. ASF/SF2 is an essential splicing factor that plays an important role in cellular and viral mRNA splicing. To determine whether CDK13 regulates splicing by affecting ASF/SF2 phosphorylation, we performed an in vitro kinase assay where we incubated active CDK13 with purified GST-ASF/SF2 and showed that ASF/SF2 phosphorylation is ninefold higher when ASF/SF2 was incubated with the complex from cells overexpressing HA-CDK13 than when it was incubated with the mock-transfected complex (Fig. 7A). Figure 7B shows that IP using HA Ab is able to specifically pull down CDK13 from HeLa-T4+ cells overexpressing HA-CDK13 but not from HeLa-T4+ cells alone. To further show specificity, we transfected a mutant CDK13 construct, followed by IP and its use in an in vitro kinase assay. Figure 7C shows that only wt and not mutant CDK13 was able to phosphorylate SF2 in vitro. Finally, since CDK13 was found to interact with p32 and Tat, we wanted to assess whether CDK13 could phosphorylate these two proteins. Figure 7D indicates that CDK13 can phosphorylate only the short form of p32 and not the long form. Interestingly and unlike other CDKs including CDK9 and CDK2, CDK13 was not able to phosphorylate Tat itself or the C-terminal domain, indicating the substrate specificity of the kinase activity of CDK13.

FIG. 7.

CDK13 phosphorylates ASF/SF2 in vitro. (A) CDK13 was IPed from HLM-1 cells transfected with HA-CDK13 or mock transfected using an Ab against HA epitope. The IPed complex was incubated with purified GST-SF2 and an in vitro kinase assay was performed in the presence of labeled ATP. The reaction products were separated on a 4 to 20% Tris-glycine polyacrylamide gel and the gel was dried and exposed to a phosphorimager cassette in order to detect the phosphorylated products. (B) Western blotting using an anti-CDK13 Ab was performed on the complex IPed with the anti-HA Ab described for panel A to confirm that the HA Ab pulled down CDK13. (C) Experiment similar to that described for panel A, in which either HA-CDK13, a mutant CDK13 (CDC2L5C Ter), or mock-transfected cells were processed and IPed for kinase activity on GST-SF2. The data are averages from three independent experiments. (D) An in vitro kinase assay was performed as described for panel A by use of IPed HA-CDK13 with GST, GST-SF-2, GST-C-terminal domain, GST-p32L, GST-p32S, and purified Tat as substrates. Purified CDK2/cylin E complex (0.5 μg) was incubated with Tat (0.5 μg) as a control.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we have demonstrated the molecular mechanism by which the viral protein Tat regulates HIV-1 mRNA splicing through its interaction with CDK13. We have previously established that lysines 50 and 51 of Tat mediate Tat binding to the splicing regulator p32 and that mutation at these residues affects viral mRNA. Comparing the splicing profiles of wt NL4-3 and double mutant NL4-3 (K50, 51A) viruses, we demonstrated that the double mutation differentially decreases the production of proteins encoded by US and singly spliced mRNAs (Gag and Env, respectively) and increases proteins encoded by doubly spliced mRNAs (Nef) (Fig. 1A). This decrease in Gag and Env production was not due to an effect of the mutation on the US and singly spliced mRNA stability, as overexpression of Rev did not revert the level of Gag and Env expressed from the mutant virus to levels comparable to those seen for the wt virus (Fig. 1B). In addition, sequence analysis of the Tat gene indicated that the two point mutations introduced to mutate the lysine 50 and 51 into alanines did not affect any splicing regulatory sequences present in the Tat gene, including the exon splice enhancer ESS2 or the splice acceptors A4c, A4b, and A5. A point mutation was introduced in Rev at serine 5, which was mutated into arginine; however, this mutation does not seem to have a functional implication, since overexpression of wt Rev with the pNL4-3 mutant did not change the viral expression pattern compared to what was seen for the mutant virus alone. Based on these results, we believe that Tat acetylated at positions 50 and 51 is able to inhibit viral splicing by binding to the splicing inhibitor p32. p32 was shown to inhibit splicing by preventing the phosphorylation of the splicing factor ASF/SF2 (46). Recently, p32 was found to interact with CDK13, a novel CDK, in a yeast two-hybrid system (22). Although the role of CDKs and their associated cyclins is essential for cell cycle and RNA transcription regulation (reviewed in reference 47), evidence has emerged that they are also involved in the regulation of RNA splicing (reviewed in reference 39). For example, CDK11p110 colocalizes with the general splicing factor RNPS1 and increases splicing efficiency, possibly through the phosphorylation of the SR protein 9G8 (28). In addition, blocking the activity of cyclin L1, a cyclin partner of CDK11p110, inhibits the second step (cutting of the lariat exon intermediate and ligation of adjacent exons) of pre-mRNA splicing in an in vitro assay (19). A recently identified Cdc2-related kinase, CrkRS or CDK12, is also implicated in the regulation of RNA splicing (34). In fact, CDK12 localizes in nuclear speckles and phosphorylates the C-terminal domain of RNA polymerase II and the splicing factor ASF/SF2 in vitro, suggesting a role in transcription and splicing. CDK12 was also shown to interact with cyclins L1 and L2. Furthermore, another CDK, namely, CDK13, was identified. It contains an RS domain characteristic of the SR protein family of splicing factors. CDK13 was also shown to have cyclin L as a partner, interact directly with the splicing regulator p32, and regulate splicing both in vitro and in vivo (22).

Since we established that Tat interacted with p32 on one hand and that p32 interacts with CDK13 on the other, we wanted to study whether Tat, p32, and CDK13 are part of the same complex. In fact, separating cell extract by size exclusion chromatography, we found that the three proteins comigrated in the same fraction and complexed (Fig. 2C and D), indicating that Tat, p32, and CDK13 may be part of the same complex. In addition, we demonstrated that CDK13 interacted with the viral protein Tat both in vitro and in vivo (Fig. 2). Since CDK13 has been shown to interact with the splicing regulator p32 and to regulate mRNA splicing, we hypothesized that this interaction might have an implication for HIV-1 mRNA splicing. In fact, our results show that CDK13 increases viral splicing and favors the production of the doubly spliced mRNA-encoded protein Nef. Indeed, we have shown that overexpression of CDK13 led to the accumulation of spliced viral mRNA and prevented the shift to US mRNA observed in the absence of CDK13 (Fig. 3A). CDK13 also disrupted the splicing pattern of HIV-1 mRNA, as indicated by the dose-dependent decrease of the US/S ratio of viral mRNA in the presence of increasing amounts of CDK13 (Fig. 3B). The net effect of the disruption of HIV-1 mRNA splicing seems to be an overall decrease in viral mRNA, protein, and virus production (Fig. 3A and 5).

Several CDKs and non-cyclin-dependent kinases have been shown to increase splicing by affecting the phosphorylation of splicing factors. p32 is a splicing regulator that inhibits splicing by preventing the phosphorylation of the splicing factor ASF/SF2. Since CDK13 is able to bind p32, we wanted to determine whether CDK13 is able to phosphorylate ASF/SF2. Indeed, in an in vitro kinase assay, we demonstrated that CDK13 phosphorylates ASF/SF2 (Fig. 5) and that its kinase activity was inhibited by several CDK inhibitors (data not shown).

The phosphorylation of ASF/SF2 is a fundamental event in the splicing activity of this protein as well as other SR proteins. Several kinases are involved in the phosphorylation of ASF/SF2, including SRPK family kinases (25, 37), mammalian PRP4 (36), and a family of kinases termed Clk (Cdc2-like kinase), or LAMMER kinases from the consensus motif, consisting of four members (Clk1 to -4) (15, 42). SR proteins are known to be phosphorylated, predominantly on serine residues of the RS domain (15, 24). At least eight members of the family, including ASF/SF2, SC35, and SRp40, are recognized by mAb104, a monoclonal Ab specific for the phosphoepitope present in all SR proteins (62). Spliceosome assembly may be mediated by phosphorylation of SR proteins that facilitate specific protein interactions, while preventing SR proteins from binding randomly to RNA. Once a functional spliceosome has formed, dephosphorylation of SR proteins appears to be necessary to allow the transesterification reactions to occur (10). Therefore, the sequential phosphorylation and dephosphorylation of SR proteins may mark the transition between stages in each round of the splicing reaction.

Several viral proteins have been reported to interact with and modulate the activity of splicing factors. In fact, HIV-2 Gag interacts specifically with PRP4, a serine/threonine kinase, and inhibits PRP4-mediated phosphorylation of splicing factor ASF/SF2, leading to an overall downregulation of splicing (4). Furthermore, SR proteins purified from adenovirus- or vaccinia virus-infected cells are hypophosphorylated and functionally inactivated as splicing regulatory proteins. In fact, adenovirus makes extensive use of RNA splicing to produce a complex set of spliced mRNAs during virus replication and remodels the host cell RNA splicing machinery to orchestrate the shift from the early to the late profile of viral mRNA accumulation. Recent progress has to a large extent focused on the mechanisms regulating E1A and L1 alternative splicing. Interestingly, regulation of SR protein activities during adenoviral infection occurs through dephosphorylation mediated by the viral E4-ORF4 protein and cellular protein phosphatase 2A (21). Virus-induced dephosphorylation renders SR proteins inactive as both splicing activators and repressors and thus alters the alternative splicing of the viral pre-mRNA. In an analogous situation, the herpes simplex virus type 1 protein ICP27 modifies SRPK1 activity, resulting in hypophosphorylation of SR proteins, impairing their ability to function in spliceosome assembly (55).

Doubly spliced transcripts Tat, Rev, and Nef were shown to be regulated by ASF/SF2. The two silencer elements (ESS3 and ISS) and two enhancer elements [ESE2 and ESE3/(GAA)3] were identified at the splice acceptor site A7, which is involved in the production of Tat and Rev. While hnRNP A1 binds ISS and ESS3 and is involved in the inhibitory process, ASF/SF2 activates site A7 utilization (29, 52). Based on that fact, we tested the effect of CDK13 on the splicing of an HIV-1 minigene containing the splice donor D4 and the splice acceptor A7. In fact, overexpression of CDK13 in the presence of wt Tat increased the utilization of A7, and thereby splicing, potentially through the increased phosphorylation of ASF/SF2 (Fig. 4). This increase in the splicing of Nef mediated by CDK13 did not happen in the absence of Tat or the presence of that Tat 50/51 double mutant. These results indicate that lysine 50 and 51 of Tat are important for the CDK13-mediated increase of Nef splicing. These results open several questions about the involvement of Tat acetylation in the regulation of splicing. Since CDK13 seems to be dependent on Tat acetylation for its effect on splicing, does that imply that the interaction of AcTat with p32 competes with the ability of CDK13 to bind to Tat and thus inhibits its splicing effect? Does Tat act as a chaperone molecule (analogous to Tat's ability to bind to Dicer and control RNA interference machinery) that brings p32 and CDK13 into the same complex in order for the CDK13 activity to be inhibited by p32? Increasing evidence supports the involvement of Tat in the regulation of the activity of other proteins involved in RNA processing, such as Dicer. Tat has been shown to have an RNA silencing suppressor function by modulating the activity of Dicer (3, 26). Similarly, other viral proteins have also been shown to act as RNA silencing suppressors, including Ebola virus VP35 and influenza A virus NS1 proteins (8, 26, 38).

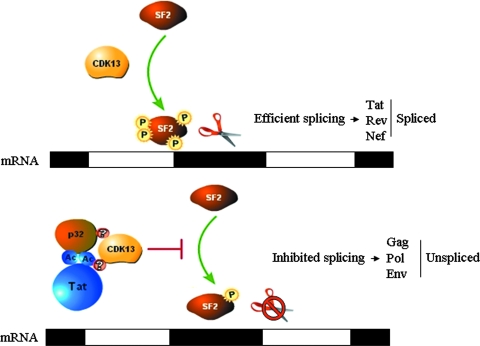

Since CDK13 seems to promote viral splicing by phosphorylating ASF/SF2 and being able to bind Tat and p32, we suggest a model in which the AcTat-p32 complex sequesters CDK13 into an inhibitory complex, preventing it from phosphorylating ASF/SF2. In our model, illustrated in Fig. 8, the accumulation of viral mRNAs is subjected to a temporal regulation, a mechanism that ensures that proteins that are needed at certain stages of the viral life cycle are produced. According to our study, we suggest that early during infection, CDK13 induces the splicing of HIV-1 mRNA through the phosphorylation of ASF/SF2, leading to the production of doubly spliced mRNA. Once Tat accumulates in the infected cells, it recruits CDK13 along with p32 in an inhibitory complex where CDK13 is not able to phosphorylate ASF/SF2, and thus splicing is inhibited. Splicing inhibition and the production of US mRNA are characteristic of the late infection stage, where mRNAs encoding structural proteins predominate. Second, according to our results CDK13 seems to act as a restriction factor that prevents viral replication, potentially by mediating excessive splicing. By recruiting CDK13 into an inhibitory complex, Tat seems to be rescuing the virus and ensuring its proper replication in a permissive environment. Further studies need to be done to determine whether the AcTat-p32 complex targets CDK13 for degradation or whether it binds to its catalytic domains, preventing its kinase activity. In addition, several questions still need to be addressed in future. Besides its role in splicing regulation, does CDK13 have any potential role in viral transactivation? Finally, we found that several CDK inhibitors were able to inhibit or activate CDK13 activity (data not shown). Could these drugs be used to target and activate latent viral reservoirs or decrease viral replication by increasing CDK13 activity? Current efforts are under way to address these issues.

FIG. 8.

Model illustrating the effect of Tat-p32-CDK13 interaction on the regulation of HIV-1 splicing. In the absence of the AcTat-p32 complex, CDK13 mediates ASF/SF2 phosphorylation, needed for efficient splicing. AcTat-p32 sequesters CDK13 away from its substrate, ASF/SF2, and thus inhibits CDK13-mediated ASF/SF2 phosphorylation.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the NIH AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program for providing us with many of the reagents used in this study.

This work was supported by GW, Keck, Conrad, REF, and NIH grants to F.K.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 14 May 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ammosova, T., R. Berro, M. Jerebtsova, A. Jackson, S. Charles, Z. Klase, W. Southerland, V. R. Gordeuk, F. Kashanchi, and S. Nekhai. 2006. Phosphorylation of HIV-1 Tat by CDK2 in HIV-1 transcription. Retrovirology 378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Benkirane, M., R. F. Chun, H. Xiao, V. V. Ogryzko, B. H. Howard, Y. Nakatani, and K. T. Jeang. 1998. Activation of integrated provirus requires histone acetyltransferase. p300 and P/CAF are coactivators for HIV-1 Tat. J. Biol. Chem. 27324898-24905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bennasser, Y., S. Y. Le, M. Benkirane, and K. T. Jeang. 2005. Evidence that HIV-1 encodes an siRNA and a suppressor of RNA silencing. Immunity 22607-619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bennett, E., A. Lever, and J. Allen. 2004. Human immunodeficiency virus type 2 Gag interacts specifically with PRP4, a serine-threonine kinase, and inhibits phosphorylation of splicing factor SF2. J. Virol. 7811303-11312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berro, R., K. Kehn, C. de la Fuente, A. Pumfery, R. Adair, J. Wade, A. M. Colberg-Poley, J. Hiscott, and F. Kashanchi. 2006. Acetylated Tat regulates human immunodeficiency virus type 1 splicing through its interaction with the splicing regulator p32. J. Virol. 803189-3204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bieniasz, P., and B. Cullen. 2000. Multiple blocks to human immunodeficiency virus type 1 replication in rodent cells. J. Virol. 749868-9877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bohne, J., H. Wodrich, and H. G. Krausslich. 2005. Splicing of human immunodeficiency virus RNA is position-dependent suggesting sequential removal of introns from the 5′ end. Nucleic Acids Res. 33825-837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bucher, E., H. Hemmes, P. de Haan, R. Goldbach, and M. Prins. 2004. The influenza A virus NS1 protein binds small interfering RNAs and suppresses RNA silencing in plants. J. Gen. Virol. 85983-991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Caceres, J. F., G. R. Screaton, and A. R. Krainer. 1998. A specific subset of SR proteins shuttles continuously between the nucleus and the cytoplasm. Genes Dev. 1255-66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cao, W., S. F. Jamison, and M. A. Garcia-Blanco. 1997. Both phosphorylation and dephosphorylation of ASF/SF2 are required for pre-mRNA splicing in vitro. RNA 31456-1467. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chackerian, B., E. M. Long, P. A. Luciw, and J. Overbaugh. 1997. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 coreceptors participate in postentry stages in the virus replication cycle and function in simian immunodeficiency virus infection. J. Virol. 713932-3939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chandler, S. D., A. Mayeda, J. M. Yeakley, A. R. Krainer, and X. D. Fu. 1997. RNA splicing specificity determined by the coordinated action of RNA recognition motifs in SR proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 943596-3601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen, H. H., Y. C. Wang, and M. J. Fann. 2006. Identification and characterization of the CDK12/cyclin L1 complex involved in alternative splicing regulation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 262736-2745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen, H. H., Y. H. Wong, A. M. Geneviere, and M. J. Fann. 2007. CDK13/CDC2L5 interacts with L-type cyclins and regulates alternative splicing. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 354735-740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Colwill, K., T. Pawson, B. Andrews, J. Prasad, J. L. Manley, J. C. Bell, and P. I. Duncan. 1996. The Clk/Sty protein kinase phosphorylates SR splicing factors and regulates their intranuclear distribution. EMBO J. 15265-275. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cujec, T. P., H. Okamoto, K. Fujinaga, J. Meyer, H. Chamberlin, D. O. Morgan, and B. M. Peterlin. 1997. The HIV transactivator TAT binds to the CDK-activating kinase and activates the phosphorylation of the carboxy-terminal domain of RNA polymerase II. Genes Dev. 112645-2657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Deng, L., C. de la Fuente, P. Fu, L. Wang, R. Donnelly, J. D. Wade, P. Lambert, H. Li, C. G. Lee, and F. Kashanchi. 2000. Acetylation of HIV-1 Tat by CBP/P300 increases transcription of integrated HIV-1 genome and enhances binding to core histones. Virology 277278-295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Deng, L., D. Wang, C. de la Fuente, L. Wang, H. Li, C. G. Lee, R. Donnelly, J. D. Wade, P. Lambert, and F. Kashanchi. 2001. Enhancement of the p300 HAT activity by HIV-1 Tat on chromatin DNA. Virology 289312-326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dickinson, L. A., A. J. Edgar, J. Ehley, and J. M. Gottesfeld. 2002. Cyclin L is an RS domain protein involved in pre-mRNA splicing. J. Biol. Chem. 27725465-25473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Duncan, P. I., D. F. Stojdl, R. M. Marius, and J. C. Bell. 1997. In vivo regulation of alternative pre-mRNA splicing by the Clk1 protein kinase. Mol. Cell. Biol. 175996-6001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Estmer Nilsson, C., S. Petersen-Mahrt, C. Durot, R. Shtrichman, A. R. Krainer, T. Kleinberger, and G. Akusjarvi. 2001. The adenovirus E4-ORF4 splicing enhancer protein interacts with a subset of phosphorylated SR proteins. EMBO J. 20864-871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Even, Y., S. Durieux, M. L. Escande, J. C. Lozano, G. Peaucellier, D. Weil, and A. M. Geneviere. 2006. CDC2L5, a Cdk-like kinase with RS domain, interacts with the ASF/SF2-associated protein p32 and affects splicing in vivo. J. Cell. Biochem. 99890-904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Graveley, B. R. 2000. Sorting out the complexity of SR protein functions. RNA 61197-1211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gui, J. F., W. S. Lane, and X. D. Fu. 1994. A serine kinase regulates intracellular localization of splicing factors in the cell cycle. Nature 369678-682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gui, J. F., H. Tronchere, S. D. Chandler, and X. D. Fu. 1994. Purification and characterization of a kinase specific for the serine- and arginine-rich pre-mRNA splicing factors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 9110824-10828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Haasnoot, J., W. de Vries, E. J. Geutjes, M. Prins, P. de Haan, and B. Berkhout. 2007. The Ebola virus VP35 protein is a suppressor of RNA silencing. PLoS Pathog. 3e86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Honore, B., P. Madsen, H. Rasmussen, J. Vandekerckhove, J. Celis, and H. Leffers. 1993. Cloning and expression of a cDNA covering the complete coding region of the P32 subunit of human pre-mRNA splicing factor SF2. Gene 134283-287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hu, D., A. Mayeda, J. H. Trembley, J. M. Lahti, and V. J. Kidd. 2003. CDK11 complexes promote pre-mRNA splicing. J. Biol. Chem. 2788623-8629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jacquenet, S., D. Decimo, D. Muriaux, and J. L. Darlix. 2005. Dual effect of the SR proteins ASF/SF2, SC35 and 9G8 on HIV-1 RNA splicing and virion production. Retrovirology 233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kashanchi, F., S. N. Khleif, J. F. Duvall, M. R. Sadaie, M. F. Radonovich, M. Cho, M. A. Martin, S. Y. Chen, R. Weinmann, and J. N. Brady. 1996. Interaction of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Tat with a unique site of TFIID inhibits negative cofactor Dr1 and stabilizes the TFIID-TFIIA complex. J. Virol. 705503-5510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kiernan, R. E., C. Vanhulle, L. Schiltz, E. Adam, H. Xiao, F. Maudoux, C. Calomme, A. Burny, Y. Nakatani, K. T. Jeang, M. Benkirane, and C. Van Lint. 1999. HIV-1 tat transcriptional activity is regulated by acetylation. EMBO J. 186106-6118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim, S. Y., R. Byrn, J. Groopman, and D. Baltimore. 1989. Temporal aspects of DNA and RNA synthesis during human immunodeficiency virus infection: evidence for differential gene expression. J. Virol. 633708-3713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Klotman, M. E., S. Kim, A. Buchbinder, A. DeRossi, D. Baltimore, and F. Wong-Staal. 1991. Kinetics of expression of multiply spliced RNA in early human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection of lymphocytes and monocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 885011-5015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ko, T. K., E. Kelly, and J. Pines. 2001. CrkRS: a novel conserved Cdc2-related protein kinase that colocalises with SC35 speckles. J. Cell Sci. 1142591-2603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Koizumi, J., Y. Okamoto, H. Onogi, A. Mayeda, A. R. Krainer, and M. Hagiwara. 1999. The subcellular localization of SF2/ASF is regulated by direct interaction with SR protein kinases (SRPKs). J. Biol. Chem. 27411125-11131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kojima, T., T. Zama, K. Wada, H. Onogi, and M. Hagiwara. 2001. Cloning of human PRP4 reveals interaction with Clk1. J. Biol. Chem. 27632247-32256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kuroyanagi, N., H. Onogi, T. Wakabayashi, and M. Hagiwara. 1998. Novel SR-protein-specific kinase, SRPK2, disassembles nuclear speckles. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 242357-364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li, W. X., H. Li, R. Lu, F. Li, M. Dus, P. Atkinson, E. W. Brydon, K. L. Johnson, A. Garcia-Sastre, L. A. Ball, P. Palese, and S. W. Ding. 2004. Interferon antagonist proteins of influenza and vaccinia viruses are suppressors of RNA silencing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1011350-1355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Loyer, P., J. H. Trembley, R. Katona, V. J. Kidd, and J. M. Lahti. 2005. Role of CDK/cyclin complexes in transcription and RNA splicing. Cell. Signal. 171033-1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Marcello, A., M. Zoppe, and M. Giacca. 2001. Multiple modes of transcriptional regulation by the HIV-1 Tat transactivator. IUBMB Life 51175-181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Marzio, G., M. Tyagi, M. I. Gutierrez, and M. Giacca. 1998. HIV-1 tat transactivator recruits p300 and CREB-binding protein histone acetyltransferases to the viral promoter. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 9513519-13524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nayler, O., S. Stamm, and A. Ullrich. 1997. Characterization and comparison of four serine- and arginine-rich (SR) protein kinases. Biochem. J. 326693-700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nekhai, S., R. R. Shukla, and A. Kumar. 1997. A human primary T-lymphocyte-derived human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Tat-associated kinase phosphorylates the C-terminal domain of RNA polymerase II and induces CAK activity. J. Virol. 717436-7441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Okamoto, Y., H. Onogi, R. Honda, H. Yasuda, T. Wakabayashi, Y. Nimura, and M. Hagiwara. 1998. cdc2 kinase-mediated phosphorylation of splicing factor SF2/ASF. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 249872-878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ott, M., M. Schnolzer, J. Garnica, W. Fischle, S. Emiliani, H. R. Rackwitz, and E. Verdin. 1999. Acetylation of the HIV-1 Tat protein by p300 is important for its transcriptional activity. Curr. Biol. 91489-1492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Petersen-Mahrt, S., C. Estmer, C. Ohrmalm, D. Matthews, W. Russell, and G. Akusjarvi. 1999. The splicing factor-associated protein, p32, regulates RNA splicing by inhibiting ASF/SF2 RNA binding and phosphorylation. EMBO J. 181014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pumfery, A., C. de la Fuente, R. Berro, S. Nekhai, F. Kashanchi, and S. H. Chao. 2006. Potential use of pharmacological cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors as anti-HIV therapeutics. Curr. Pharm. Des. 121949-1961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pumfery, A., L. Deng, A. Maddukuri, C. de la Fuente, H. Li, J. D. Wade, P. Lambert, A. Kumar, and F. Kashanchi. 2003. Chromatin remodeling and modification during HIV-1 Tat-activated transcription. Curr. HIV Res. 1343-362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Purcell, D. F., and M. A. Martin. 1993. Alternative splicing of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 mRNA modulates viral protein expression, replication, and infectivity. J. Virol. 676365-6378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Reed, R. 1996. Initial splice-site recognition and pairing during pre-mRNA splicing. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 6215-220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Riggs, N., S. Little, D. Richman, and J. Guatelli. 1994. Biological importance and cooperativity of HIV-1 regulatory gene splice acceptors. Virology 202264-271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ropers, D., L. Ayadi, R. Gattoni, S. Jacquenet, L. Damier, C. Branlant, and J. Stevenin. 2004. Differential effects of the SR proteins 9G8, SC35, ASF/SF2, and SRp40 on the utilization of the A1 to A5 splicing sites of HIV-1 RNA. J. Biol. Chem. 27929963-29973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rossi, F., E. Labourier, T. Forne, G. Divita, J. Derancourt, J. F. Riou, E. Antoine, G. Cathala, C. Brunel, and J. Tazi. 1996. Specific phosphorylation of SR proteins by mammalian DNA topoisomerase I. Nature 38180-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Santiago, F., E. Clark, S. Chong, C. Molina, F. Mozafari, R. Mahieux, M. Fujii, N. Azimi, and F. Kashanchi. 1999. Transcriptional up-regulation of the cyclin D2 gene and acquisition of new cyclin-dependent kinase partners in human T-cell leukemia virus type 1-infected cells. J. Virol. 739917-9927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sciabica, K. S., Q. J. Dai, and R. M. Sandri-Goldin. 2003. ICP27 interacts with SRPK1 to mediate HSV splicing inhibition by altering SR protein phosphorylation. EMBO J. 221608-1619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shen, H., and M. R. Green. 2004. A pathway of sequential arginine-serine-rich domain-splicing signal interactions during mammalian spliceosome assembly. Mol. Cell 16363-373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shen, H., J. L. Kan, and M. R. Green. 2004. Arginine-serine-rich domains bound at splicing enhancers contact the branchpoint to promote prespliceosome assembly. Mol. Cell 13367-376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Smith, J., A. Azad, and N. Deacon. 1992. Identification of two novel human immunodeficiency virus type 1 splice acceptor sites in infected T cell lines. J. Gen. Virol. 731825-1828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Stoltzfus, C. M., and J. M. Madsen. 2006. Role of viral splicing elements and cellular RNA binding proteins in regulation of HIV-1 alternative RNA splicing. Curr. HIV Res. 443-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wu, J. Y., and T. Maniatis. 1993. Specific interactions between proteins implicated in splice site selection and regulated alternative splicing. Cell 751061-1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Xiao, S. H., and J. L. Manley. 1997. Phosphorylation of the ASF/SF2 RS domain affects both protein-protein and protein-RNA interactions and is necessary for splicing. Genes Dev. 11334-344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zahler, A. M., W. S. Lane, J. A. Stolk, and M. B. Roth. 1992. SR proteins: a conserved family of pre-mRNA splicing factors. Genes Dev. 6837-847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zhou, M., M. A. Halanski, M. F. Radonovich, F. Kashanchi, J. Peng, D. H. Price, and J. N. Brady. 2000. Tat modifies the activity of CDK9 to phosphorylate serine 5 of the RNA polymerase II carboxyl-terminal domain during human immunodeficiency virus type 1 transcription. Mol. Cell. Biol. 205077-5086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zhu, Y., T. Pe'ery, J. Peng, Y. Ramanathan, N. Marshall, T. Marshall, B. Amendt, M. B. Mathews, and D. H. Price. 1997. Transcription elongation factor P-TEFb is required for HIV-1 tat transactivation in vitro. Genes Dev. 112622-2632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]