Abstract

In serine cycle methylotrophs, methylene tetrahydrofolate (H4F) is the entry point of reduced one-carbon compounds into the serine cycle for carbon assimilation during methylotrophic metabolism. In these bacteria, two routes are possible for generating methylene H4F from formaldehyde during methylotrophic growth: one involving the reaction of formaldehyde with H4F to generate methylene H4F and the other involving conversion of formaldehyde to formate via methylene tetrahydromethanopterin-dependent enzymes and conversion of formate to methylene H4F via H4F-dependent enzymes. Evidence has suggested that the direct condensation reaction is the main source of methylene H4F during methylotrophic metabolism. However, mutants lacking enzymes that interconvert methylene H4F and formate are unable to grow on methanol, suggesting that this route for methylene H4F synthesis should have a significant role in biomass production during methylotrophic metabolism. This problem was investigated in Methylobacterium extorquens AM1. Evidence was obtained suggesting that the existing deuterium assay might overestimate the flux through the direct condensation reaction. To test this possibility, it was shown that only minor assimilation into biomass occurred in mutants lacking the methylene H4F synthesis pathway through formate. These results suggested that the methylene H4F synthesis pathway through formate dominates assimilatory flux. A revised kinetic model was used to validate this possibility, showing that physiologically plausible parameters in this model can account for the metabolic fluxes observed in vivo. These results all support the suggestion that formate, not formaldehyde, is the main branch point for methylotrophic metabolism in M. extorquens AM1.

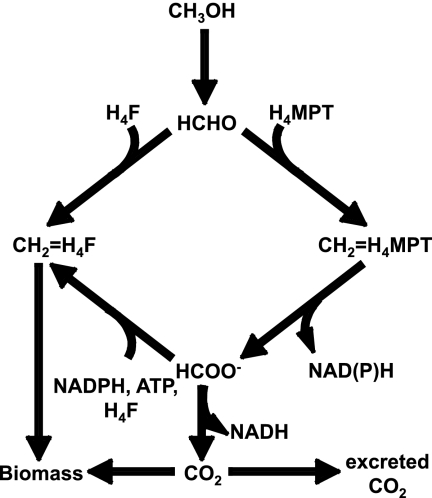

Methylobacterium extorquens AM1 is a facultative methylotroph that has served as a model system for understanding methylotrophic metabolism for many decades (1, 3, 33). One outstanding question in methylotrophic metabolism involves the route by which C1 compounds are incorporated into assimilatory metabolism. In this bacterium, methanol or methylamine is oxidized via formaldehyde and formate to CO2 for energy metabolism and carbon is assimilated via the serine cycle (Fig. 1) (1, 3, 33). The entry point into the serine cycle is methylene tetrahydrofolate (H4F). In the 1960s and 1970s, it was proposed that the main route for generating methylene H4F is the spontaneous (nonenzymatic) condensation of formaldehyde with H4F (12, 19). However, a potential alternate route exists, involving the conversion of formaldehyde to formate and then to methylene H4F (Fig. 1). This set of interconversions was shown to function in the reductive direction (25, 26), and it was suggested that this pathway might contribute to production of biomass from formate (25, 30, 38). This alternate route uses an additional ATP compared to the direct condensation route (Fig. 1), suggesting that it is more expensive energetically. The relative fluxes of these two potential routes were assessed using an in vivo deuterium labeling technique (27). This study suggested that the direct condensation of formaldehyde with H4F is the main source of methylene H4F in cells growing on methanol (27).

FIG. 1.

Traditional scheme of methylotrophic metabolism in serine cycle methylotrophs (12, 19). CH2=H4F, methylene tetrahydrofolate; CH2=H4MPT, methylene H4MPT.

However, the meaning of these results remained uncertain because mutants defective in any of the three enzymes (formyl H4F ligase [FtfL], methenyl H4F cyclohydrolase [Fch] and methylene H4F dehydrogenase [MtdA]) involved in the pathway converting formate to methylene H4F cannot grow on methanol (7, 25, 26, 32). These mutant results suggested that this alternate route of methylene H4F synthesis should play a significant role in methylotrophic metabolism. The present study addressed the role of this pathway in methylotrophic growth using a combination of flux analysis and modeling approaches.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

M. extorquens AM1 was routinely grown at 28°C in the minimal medium described previously (11), either in batch cultures, with 120 mM methanol or 15 mM succinate, or in chemostat cultures in a benchtop fermentor essentially as described previously (9, 37), with a dilution rate of 0.100 h−1 and a substrate concentration in the feed of either 25 mM methanol or 3.7 mM succinate plus 12.5 mM methanol. Methanol was measured in the effluent as described previously (23). Wild-type chemostat cultures maintained a steady-state optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of approximately 1.0. Because of the unique growth requirements of the ΔmtdA mutant (26), this strain was grown in chemostat cultures to a steady-state OD600 of approximately 0.6 with 3.7 mM succinate plus 12.5 mM methanol. The ΔftfL strain (25) was grown in a batch culture on 15 mM succinate and then pelleted, washed, and exposed to 120 mM methanol for 3 to 4 h to promote induction of C1 enzymes. The following antibiotic concentrations were used: kanamycin, 25 to 50 μg/ml, and rifamycin, 25 to 50 μg/ml.

14C-labeling experiments.

The rate of assimilation of labeled carbon from [14C]methanol was determined by incubating cell samples (OD600 between 0.2 and 1.0; high-flux samples diluted to an OD600 of 0.2 to 0.3 to avoid oxygen limitation) with 1 mM labeled methanol (1.4 μCi/μmol final specific activity) in 2-ml autosampling vials (Kimble) for 12 min at 28°C and then pipetting samples onto 0.2-μm polyvinylidene difluoride filters (Millipore), submerging the filters in scintillation fluid, and quantifying the radioactivity with one of two scintillation counters (Beckman LS3801 and Perkin-Elmer 2800TR). Experiments to determine the relative contributions of labeled methylene H4F and labeled CO2 to labeled biomass were performed by modifying a previous method (18). Prior to incubation, cells were diluted with medium bubbled with an N2-O2 gas mixture containing either 0% CO2 or 5% CO2 and then injected into vials containing the same gases.

2H-labeling experiments.

Incorporation of deuterium (2H) into serine was quantified as previously described (27). Briefly, concentrated cell suspensions were incubated with 1 mM fully deuterated methanol (CD3OD) for 20 s (unless otherwise noted) and then lysed via the addition of 3 volumes of boiling ethanol and derivatized with ethyl chloroformate and trifluoroacetic anhydride (ECF/TFAA). Fragments of ECF/TFAA-derivatized serine containing either 0, 1, or 2 deuterium atoms were quantified according to their differences in mass by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. Data were corrected for the natural abundance of heavy isotopes in the derivatized serine fragments.

Flux calculations.

Methanol input rate for methanol-limited chemostat cultures is 41.0 nmol/(ml·min). The methanol concentration in the effluent was below the detection limit (∼50 μM) of our assay (23), indicating essentially complete consumption of the methanol. For a steady-state OD600 of 0.99 (the average of nine cultures), the consumption rate therefore is 41.5 nmol/(ml·OD600·min). This methanol consumption generates a biomass flux of 18.3 nmol/(ml·OD600·min), assuming 47.33% of biomass is carbon (8), using measured dry-weight values (0.278 mg biomass per ml of culture at an OD600 of 1.0 [X. Guo and M. Lidstrom, unpublished data]) and the chemostat growth rate of 0.1 h−1. Biomass fluxes were corrected for CO2 fixation using a value of 47% of biomass carbon from CO2 (see Results).

Conversion of flux rates per culture volume to flux rates per intracellular volume.

Calculations were made assuming 4 × 108 cells per ml of culture at an OD600 of 1.0 (9) and that an M. extorquens AM1 cell may be approximated as a cylinder with a radius of 0.4 μm and length of 3 μm such that the volume of a cell is approximately 1.5 × 10−15 liter (T. Strovas, personal communication).

Measurement of the rate constant for the spontaneous reaction of formaldehyde with H4F.

The reaction of formaldehyde with H4F was monitored at pHs of 6.0, 6.5, 6.7, 7.0, and 8.0 at temperatures of 26 to 28°C. H4F powder (Sigma) was dissolved in 100 mM potassium phosphate buffer (degassed with N2) and used immediately. The final concentration of H4F was determined by measuring the A297, applying an extinction coefficient of 27 mM−1 cm−1 (41). Solutions of formaldehyde (5 to 20 mM) were also made fresh shortly before use by heating paraformaldehyde suspended in 100 mM potassium phosphate buffer (22). The assay was started by adding 100 μl of 5 to 20 mM formaldehyde to 900 μl of 10 to 20 μM H4F in a 1-ml cuvette. An increase in A295 was taken to reflect formation of methylene H4F, and the slope of this increase (ΔA295/min) and the corresponding extinction coefficient of 3.0 mM−1 cm−1 were used to calculate the rate of methylene H4F production (40).

Kinetic model of C1 metabolism.

The previous kinetic model for growth on methanol (27) was modified in several ways. Changes A through E described below represent the new “default” version of the model. In change A, concentrations of energy and redox cofactors (ADP, ATP, NAD+, NADH, NADP+, and NADPH) as measured in Escherichia coli were replaced with newly published values (9) for chemostat cultures of M. extorquens AM1. In change B, kinetic rate constants (Vmaxs) were recalculated from enzyme activities reported in previous publications (5, 6, 10, 25, 31, 32, 39, 40) using a conversion factor of 1 μmol/(min·mg protein) = 3.86 mM/s, with mM referring to intracellular volume in this case. This conversion factor is based on (i) the assumption that 50% of biomass is protein and (ii) the numbers listed above under “Conversion of flux rates per culture volume to flux rates per intracellular volume.” In change C, the spontaneous reaction rate constant for the condensation of formaldehyde with H4F was changed to the maximum measured rate of 0.08 mM−1 s−1. The spontaneous condensation of formaldehyde with tetrahydromethanopterin (H4MPT) was ignored because of its modest contribution of methylene H4MPT relative to the enzyme-catalyzed reaction (40). In change D, formylhydrolase, part of the formyltransferase/hydrolase complex (Fhc), was removed from the model because its activity is not limiting to the flux through Fhc (30) and because no experimental data on Vmax or Km are available for this reaction. In change E, new modeling was used to represent formyltetrahydrofolate ligase (FtfL). This enzyme forms a bond between formate and H4F, hydrolyzing ATP to make the reaction energetically favorable. In this respect, the enzyme is analogous to pyruvic carboxylase, which catalyzes the formation of oxaloacetate from HCO3− and pyruvate at the expense of ATP. Based on this analogy, we used equation IX-337 in Segel's enzyme kinetics text (34) to represent the flux through FtfL. The Keq value used in the modeling was taken from previous measurements (13).

One model feature retained from the previous version was the use of a formate dehydrogenase (FDH) activity that is double the published value. The published value is only for the NAD-linked FDH activity, but M. extorquens AM1 also has two other functional FDHs whose activities are not measurable, since their electron acceptors are unknown (4, 5).

To explore conditions that would predict fluxes similar to those measured, additional changes were then made in an iterative manner to generate a version that predicted measured fluxes. Changes were made solely to parameters for which some uncertainty existed for the published values. The changes made were as follows. The first change was made because total H4F and H4MPT published concentrations (39) are minimum values because (i) the method used did not capture formyl H4F or formyl H4MPT and (ii) capture of the other molecular species was likely incomplete due to the thermodynamics of the reactions involved (J. Vorholt, personal communication). Therefore, the values for total [H4F] and [H4MPT] were increased from 0.15 mM to 0.2 mM and from 0.4 mM to 0.5 mM, respectively. In the second change, involving formaldehyde-activating enzyme (Fae), the Km for H4MPT was reduced to 15% of the published value. The published value is dependent on H4MPT from another species, which is chemically different (6). In the third change, involving Ftr hydrolase complex (Fhc), the activity was increased fivefold from the published value. The enzyme is unstable, and the cofactor used is from a different species. The cofactor in M. extorquens is expected to be different (6, 30). In the fourth change, involving methenyl-H4F cyclohydrolase (Fch), the value of the Keq is pH dependent because H+ participates in the reaction (17). Since the intracellular pH of M. extorquens may be close to 6.5 (see Results), a value determined at this pH (21) was used in the model.

Statistics.

Values reported are means ± standard deviations unless otherwise indicated.

RESULTS

Reexamination of the deuterium assay for direct condensation.

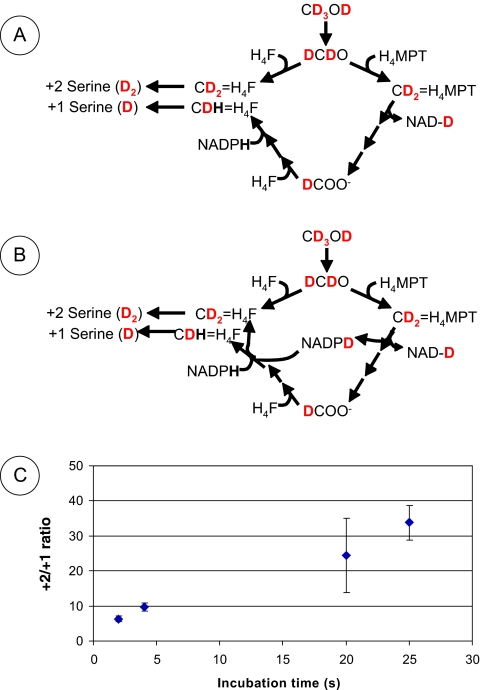

As previously described (27), in M. extorquens AM1 the serine generated from fully deuterated methanol contains two deuteriums when synthesized via the direct condensation route but only one deuterium when synthesized via formate and formyl H4F (Fig. 2A). Therefore, the +2/+1 ratio in serine provides an estimate of the ratio of flux through each route. However, a potential limitation of this estimate is the fact that if the NADPH pool becomes contaminated with deuterium as a result of NADPH production from formaldehyde oxidation via the H4MPT pathway, some +2 serine could be produced via the route involving formate and formyl H4F (27) (Fig. 2B). In the original study, it was assumed that the pool turnover would not be sufficiently rapid to affect the results of the 20-s assay. Since NADH production by methylene H4MPT dehydrogenase (MtdB) cannot be replaced by the NADPH-specific enzyme (MtdA) when overexpressed (24), it appeared that the major pyridine nucleotide produced during methanol oxidation to CO2 is NADH, not NADPH, thereby limiting the amount of deuterated NADPH that could contaminate the assay. However, since it is now known that the intracellular levels of NADPH (9) are small (<1 mM) relative to the levels of methanol consumed per second (>1 mM), rapid contamination of the NADPH pool may occur if a significant amount of NADPH is generated by MtdA/MtdB.

FIG. 2.

The assay for methylene-tetrahydrofolate synthesis routes in whole cells using deuterated methanol (CD3OD). (A) Spontaneous condensation consists of joining formaldehyde (in this case, DCDO) and H4F to form doubly deuterated methylene-tetrahydrofolate (CD2=H4F). In the alternate pathway, the one-carbon unit is joined to H4MPT, released as formate (DCOO−), and then joined to H4F, leading to the formation of CDH=H4F. In this scheme, no significant NADPH (NADPD in this experiment) is produced from the H4MPT pathway, and the ratio of doubly deuterated (D2) serine to singly deuterated (D) serine reflects relative fluxes through the spontaneous and alternate pathways. (B) In this scheme, it is assumed that significant NADPH (NADPD in this experiment) is generated by the H4MPT pathway. Contamination of the NADPH pool with deuterated NADPH produced after metabolism of deuterated methanol will increase the amount of +2 serine at the expense of +1 serine, leading to an overestimation of flux through spontaneous condensation. (C) Effect of assay incubation time on the ratio of +2 serine to +1 serine in methanol-grown cells.

We reasoned that if the NADPH pool became contaminated during the assay time, the +2/+1 ratio of serine should increase with incubation time, whereas a constant or declining +2/+1 ratio would argue against a contamination problem. Figure 2C shows that in methanol-grown cells, the ratio increases roughly linearly over the 25-s time period assessed, consistent with contamination of the NADPH pool with deuterium over time. These results suggested that flux through the direct condensation reaction might be lower than previously suggested.

Biomass assimilation flux in mutants.

To directly test the capacity for flux through the direct condensation reaction, we examined serine production and biomass flux in the ΔftfL mutant strain of M. extorquens AM1, which is defective in formyl H4F ligase. In this mutant, the alternate pathway for synthesis of methylene H4F is interrupted and the only route for methylene H4F synthesis is direct condensation. This strain is unable to grow on methanol, but it was grown on succinate and then exposed to methanol, conditions known to induce methylotrophic enzymes in this mutant (15).

If the direct condensation reaction is quantitatively important in vivo, production of +2 serine and positive biomass fluxes should be observed in the ΔftfL mutant. However, biomass flux was not significantly different from zero (0.0005 ± 0.0032 mM/s; n = 6). In addition, +2 serine was very low when CD3OD was provided to these strains, constituting only 2.6% ± 1.6% (n = 4) of the total (+0, +1, and + 2) serine detected as compared to percentages of ≥70% for wild-type cells grown on methanol. This is not inconsistent with previous results demonstrating a drop in +2 serine in this mutant compared to the wild type (27). That experiment involved cells grown on succinate, and the much lower fluxes make direct comparisons difficult. Similar results were obtained with another mutant defective in this pathway, the ΔmtdA strain, for which biomass flux was 0.0013 ± 0.0037 mM/s (n = 8) and +2 serine was 1.1% ± 0.5% (n = 3). These data are consistent with the results presented above suggesting that little methylene H4F is produced via the direct condensation route under these conditions.

Flux measurements in chemostat-grown cultures.

If the direct condensation reaction plays a minor role during methylotrophic growth, then the alternate route, involving the H4MPT and H4F pathways (Fig. 1), must be able to accommodate nearly all of the formaldehyde flux. In order to test this prediction, we carried out new flux measurements using methanol-limited chemostat-grown cells. The use of chemostat cultures allows a direct calculation of fluxes to biomass occurring in the growing cells using the substrate input rate, the dilution rate, and the amount of cells in the culture (see Materials and Methods). For methanol utilization, these calculations must be corrected for incorporation of CO2 via the serine cycle and other carboxylation reactions in the cell. To determine the proportion of biomass carbon from CO2, radioactive labeling of biomass was measured in the presence of 5% unlabeled CO2 as compared to a CO2-free environment. In the absence of external CO2, all or nearly all of the CO2 incorporated into biomass should be derived from labeled methanol and therefore should be labeled, while in high unlabeled CO2, all or nearly all of the CO2 incorporated should be unlabeled. Therefore, the difference between the two conditions should reflect the proportion of biomass derived from CO2. The average values for five replicate 14C-labeling experiments indicated that at least 47% of the biomass carbon comes from CO2, with the remainder coming from methylene H4F. These results are in keeping with previous labeling studies of flask-grown cells, suggesting approximately half of the biomass carbon comes from CO2 (18).

It has previously been shown that methanol-limited cells grown at a dilution rate equivalent to 80% of the batch culture growth rate are generally similar to batch culture cells in terms of enzyme activities and nucleotide concentrations, suggesting that these conditions are roughly comparable (9).

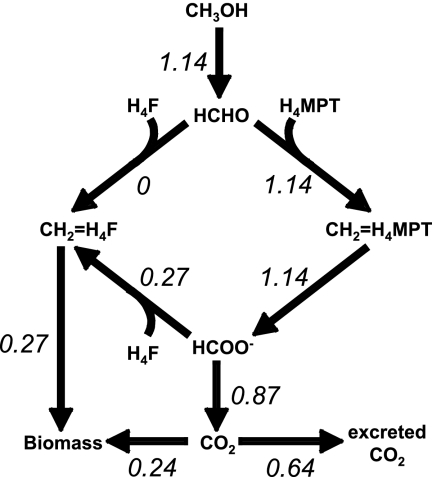

By assuming that all methanol not converted to methylene H4F is converted to CO2, a complete flux distribution for the C1 network can be calculated for cells in a methanol-limited chemostat (Fig. 3). In order to evaluate whether the H4MPT and H4F pathways could accommodate such fluxes, a kinetic model was utilized.

FIG. 3.

Distribution of fluxes (in mM/s) in wild-type M. extorquens AM1 chemostat cells grown on methanol, assuming that no methylene H4F is produced via spontaneous condensation.

Predictions from kinetic modeling.

The new data reported in this paper along with other recently published data were used to update and enhance the previous kinetic model for formaldehyde and formate partitioning during methylotrophic growth (27). One issue with the previous model was that the fitted rate constant for the spontaneous condensation reaction was 2.64 mM−1 s−1 (27), which is significantly higher than literature values. However, the literature values were determined at 20°C (2), while growth temperatures are 26 to 28°C. To explore this issue further, the nonenzymatic rate constant for the condensation of formaldehyde with H4F was measured at normal growth temperatures for M. extorquens. The rate equation for flux through this reaction is rate = V6·[H4F]·[formaldehyde], referring to the rate constant as V6 for consistency with the earlier publication (27). V6 was measured at 26 to 28°C at pH values from 6 to 8. The range of values was 0.02 to 0.08 mM−1 s−1, with the maximum value at pH 6.7. These rate constants are in reasonable agreement with the data of Blakley (2), from which a rate constant of ∼0.026 mM−1s−1 can be estimated at 20°C and pH 7.2. Therefore, the maximum rate constant measured (0.08 mM−1s−1) was used in the model, to provide a high-flux scenario.

In keeping with the other results presented in this study, this model predicted that even with the use of a relatively high rate constant for spontaneous formaldehyde condensation with H4F, this rate constant does not allow significant flux through this route unless formaldehyde rises to levels known to inhibit growth (concentrations greater than 1 mM). A number of simulations were run to identify conditions that would accommodate the measured fluxes to CO2 and biomass. Parameters for one such simulation are shown in Tables 1 and 2. In this case, published values for kinetic parameters and concentrations were used aside from the exceptions noted in Materials and Methods. Each of these changes results in values that are within expected tolerances, given the uncertainties of in vitro enzyme measurements with regard to in vivo conditions (see Materials and Methods). Using these parameters, the model predicted fluxes similar to the measured fluxes (Table 2).

TABLE 1.

Concentrations of the compounds used

TABLE 2.

Parameters used in the final model and predicted fluxes

| Enzyme(s) or reaction(s) | Parameters (reference[s])a | Flux (mM/s):

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Predicted by kinetic model | Calculated from exptl datab | ||

| Formaldehyde-activating enzyme (Fae) | Vmax, 5.4 mM/s; Keq, irrev.; Kms, 0.2 mM for formaldehyde and 0.1 mM for H4MPT (40) | 1.13 | 1.14 |

| Methylene H4MPT dehydrogenases | |||

| MtdB | Vmax, 2.3 mM/s; Keq, 174.2; Kms, 0.05 mM for methylene H4MPT and 0.2 mM for NAD+ (10) | 1.13 | 1.14 |

| MtdA | Vmax, 10.0 mM/s; Keq, 174.2; Kms, 0.02 mM for methylene H4MPT and 0.03 mM for NADP+ (39) | ||

| Methenyl H4MPT cyclohydrolase (Mch) | Vmax, 11.1 mM/s; Keq, 0.137; Km, 0.03 mM for methenyl H4MPT (6, 32) | 1.13 | 1.14 |

| Formyltransferase (Ftr) | Vmax, 9.9 mM/s; Keq, 0.204; Kms, 0.05 mM for formyl MFR and 0.03 mM for H4MPT (31) | 1.13 | 1.14 |

| Formaldehyde + H4F | Keq, NA; V6, 0.08 mM−1 s−1 (this study) | 0.01 | 0 |

| Methylene H4F dehydrogenase (MtdA) | Vmax, 6.8 mM/s; Keq, 4; Kms, 0.01 mM for NADP+ and 0.03 mM for methylene H4F (6, 39) | 0.24 | 0.27 |

| Methenyl H4F cyclohydrolase (Fch) | Vmax, 1.9 mM/s; Keq, 0.54; Km, 0.08 mM for methenyl H4F (21, 32) | 0.24 | 0.27 |

| Formyl H4F ligase (FtfL) | Vmax, 1.6 mM/s; Keq, 41; Kms, 22 mM for formate, 0.8 mM for H4F, 0.021 mM for ATP, and 2 mM for Pi (13, 25) | 0.24 | 0.27 |

| FDH | Vmax, 1.2 mM/s; Keq, irrev.; Km, 1.6 mM for formate (5, 20) | 0.88 | 0.87 |

| Serine hydroxymethyltransferase (GlyA) | Vmax, 20 mM/s; Keq, NA; Km, 0.16 mM for methylene H4F (fitted as in reference 27) | 0.25 | 0.27 |

DISCUSSION

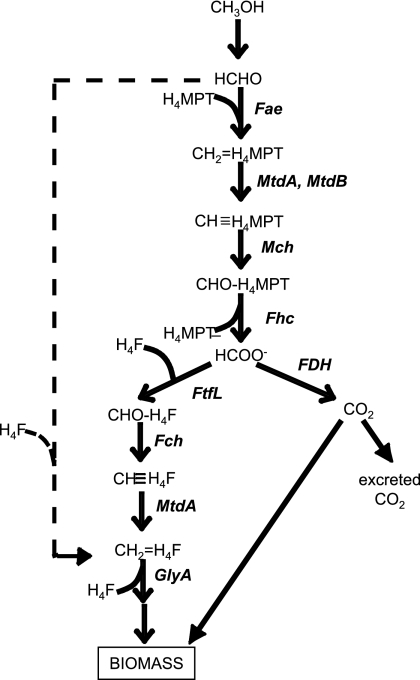

In this study, the significance in methylotrophic metabolism of the direct condensation route for synthesis of methylene H4F was assessed in M. extorquens AM1. We first obtained evidence that the deuterated methanol assay might overestimate the extent of the direct condensation reaction. Exact determinations with deuterated substrates are difficult, due to the possibility of differential isotope effects, but the data are consistent with an overestimation. An alternative approach to measuring flux through this reaction is to measure it in the ΔftfL mutant defective in the alternate route involving the H4F pathway. The results from these analyses demonstrate that under these conditions, the flux through the direct condensation route is minor. However, the ΔftfL mutant does not grow on methanol and must be tested in cells that have been grown on succinate, washed, and incubated with methanol. These conditions are known to induce methylotrophic enzymes in this mutant (16), but the flux capacity through the assimilatory pathways is unknown. Removal of methylene H4F by the serine cycle is likely to be important to sustain flux through this route (27). In addition, if an enzyme exists that converts formaldehyde plus H4F to methylene H4F, it may not be fully induced under these conditions. Therefore, these results do not rule out a higher flux through this route in the wild type during growth on methanol. However, even if the contribution of this route to the synthesis of methylene H4F increases an order of magnitude during growth on methanol, the alternate route, including the enzymes Fae, MtdA/MtdB, Mch, Fhc, FtfL, Fch, and MtdA (Fig. 4), should dominate the total biomass production. This suggestion is supported by the kinetic model generated in this study, which predicts that this alternate route can support the measured fluxes during methylotrophic growth using kinetic and cofactor concentration parameters that are within known or predicted ranges. In addition, these results explain the finding that FtfL, Fch, and MtdA mutants are all unable to grow on methanol.

FIG. 4.

Proposed scheme of methylotrophic metabolism in M. extorquens AM1 showing formate (HCOO−) as the branch point between assimilatory and dissimilatory metabolism.

Although our results suggest that the spontaneous condensation reaction is not an important source of methylene H4F under standard lab culture conditions, it is still possible that it serves as an overflow valve for transient episodes of formaldehyde overproduction. Formaldehyde overproduction might occur following transient exposure to methanol, due to the high methanol dehydrogenase activity in methanol-limited cells (9). Transient methanol exposure is known to occur under natural conditions for these bacteria. Methylobacterium strains are commonly found on leaf surfaces, apparently growing on methanol emitted from stomata (35), and methanol emission from leaves is episodic (28). It is possible that under such conditions the spontaneous condensation reaction would play a role in formaldehyde detoxification.

These results suggesting that, under laboratory growth conditions, methylene H4F is mainly formed by the route involving the H4MPT and H4F pathways lead to the suggestion that formate represents the primary metabolic branch point between assimilation of C1 units into biomass (via methylene H4F and the serine cycle) and dissimilation to CO2 for energy generation in this bacterium (Fig. 4). The linear conversion of formaldehyde to formate by the high-capacity enzymes of the H4MPT pathway is a straightforward but effective method to maintain high fluxes of formaldehyde without allowing its accumulation. The disadvantage is that it requires an extra ATP for every formaldehyde assimilated, compared to a direct condensation route. Since growth on methanol is predicted to be limited by reducing power rather than ATP (36), it is possible that the tradeoffs are positive for metabolism as a whole.

Optimal partitioning of formate between these two branches may require extensive control of the relevant branch point enzymes, namely, FtfL, Fch, and MtdA for the H4F pathway, and FDH. The importance of FDH is suggested by the presence of four isoforms in M. extorquens AM1, which vary greatly in terms of their expression patterns, dependence on cofactors (NAD+) and metal ions (molybdenum and tungsten), and mutant phenotypes (4, 5). These results now direct attention to these enzymes as the likely main control points for balancing of metabolism during methylotrophic growth in M. extorquens AM1.

Acknowledgments

We thank Xiaofeng Guo, Yoko Okubo, Tim Strovas, and Julia Vorholt for sharing unpublished data; Ludmila Chistoserdova, Marina Kalyuzhnaya, Chris Marx, and Julia Vorholt for discussions of the experimental work; and Stephen Van Dien for assistance with the kinetic model.

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (GM070297 to G.J.C. and GM58933 to M.E.L.).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 23 May 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anthony, C. 1982. The biochemistry of methylotrophs. Academic Press, New York, NY.

- 2.Blakley, R. L. 1959. The reaction of tetrahydropteroylglutamic acid and related hydropteridines with formaldehyde. Biochem. J. 72707-715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chistoserdova, L., S.-W. Chen, A. Lapidus, and M. E. Lidstrom. 2003. Methylotrophy in Methylobacterium extorquens AM1 from a genomic point of view. J. Bacteriol. 1852980-2987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chistoserdova, L., G. J. Crowther, J. A. Vorholt, E. Skovran, J.-C. Portais, and M. E. Lidstrom. 2007. Identification of a fourth formate dehydrogenase in Methylobacterium extorquens AM1 and confirmation of the essential role of formate oxidation in methylotrophy. J. Bacteriol. 1899076-9081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chistoserdova, L., M. Laukel, J.-C. Portais, J. A. Vorholt, and M. E. Lidstrom. 2004. Multiple formate dehydrogenase enzymes in the facultative methylotroph Methylobacterium extorquens AM1 are dispensable for growth on methanol. J. Bacteriol. 18622-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chistoserdova, L., J. A. Vorholt, R. K. Thauer, and M. E. Lidstrom. 1998. C1 transfer enzymes and coenzymes linking methylotrophic bacteria and methanogenic Archaea. Science 28199-102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chistoserdova, L. V., and M. E. Lidstrom. 1994. Genetics of the serine cycle in Methylobacterium extorquens AM1: identification of sgaA and mtdA and sequences of sgaA, hprA, and mtdA. J. Bacteriol. 1761957-1968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goldberg, I., J. S. Rock, A. Ben-Bassat, and R. I. Mateles. 1976. Bacterial yields on methanol, methylamine, formaldehyde, and formate. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 181657-1668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guo, X., and M. E. Lidstrom. 2006. Physiological analysis of Methylobacterium extorquens AM1 grown in continuous and batch cultures. Arch. Microbiol. 186139-149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hagemeier, C. H., L. Chistoserdova, M. E. Lidstrom, R. K. Thauer, and J. A. Vorholt. 2000. Characterization of a second methylene tetrahydromethanopterin dehydrogenase from Methylobacterium extorquens AM1. Eur. J. Biochem. 2673762-3769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harder, W., M. Attwood, and J. R. Quayle. 1973. Methanol assimilation by Hyphomicrobium spp. J. Gen. Microbiol. 78155-163. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heptinstall, J., and J. R. Quayle. 1970. Pathways leading to and from serine during growth of Pseudomonas AM1 on C1 compounds or succinate. Biochem. J. 117563-572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Himes, R. H., and J. C. Rabinowitz. 1962. Formyltetrahydrofolate synthetase. II. Characteristics of the enzyme and the enzymic reaction. J. Biol. Chem. 2372903-2914. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reference deleted.

- 15.Kalyuzhnaya, M. G., and M. E. Lidstrom. 2003. QscR, a LysR-type transcriptional regulator and CbbR homolog, is involved in regulation of the serine cycle genes in Methylobacterium extorquens AM1. J. Bacteriol. 1851229-1235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kalyuzhnaya, M. G., and M. E. Lidstrom. 2005. QscR-mediated transcriptional activation of serine cycle genes in Methylobacterium extorquens AM1. J. Bacteriol. 1877511-7517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kay, L. D., M. J. Osborn, Y. Hatefi, and F. M. Huennekens. 1960. The enzymatic conversion of N5-formyl tetrahydrofolic acid (folinic acid) to N10-formyl tetrahydrofolic acid. J. Biol. Chem. 235195-201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Large, P. J., D. Peel, and J. R. Quayle. 1961. Microbial growth on C1 compounds. II. Synthesis of cell constituents by methanol- and formate-grown Pseudomonas AM 1, and methanol-grown Hyphomicrobium vulgare. Biochem. J. 81470-480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Large, P. J., and J. R. Quayle. 1963. Microbial growth on C(1) compounds. 5. Enzyme activities in extracts of Pseudomonas AM1. Biochem. J. 87386-396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Laukel, M., L. Chistoserdova, M. E. Lidstrom, and J. A. Vorholt. 2003. The tungsten-containing formate dehydrogenase from Methylobacterium extorquens AM1: purification and properties. Eur. J. Biochem. 270325-333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lombrozo, L., and D. M. Greenberg. 1967. Studies on N5,N10-methenyltetrahydrofolate cyclohydrolase. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 118297-304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ludlow, C. J., and R. B. Park. 1969. Action spectra for photosystems I and II in formaldehyde fixed algae. Plant Physiol. 44540-543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mangos, T. J., and M. J. Haas. 1996. Enzymatic determination of methanol with alcohol oxidase, peroxidase, and the chromogen 2,2′-azinobis(3-ethylbenzthiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) and its application to the determination of the methyl ester content of pectins. J. Agric. Food Chem. 442977-2981. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marx, C. J., L. Chistoserdova, and M. E. Lidstrom. 2003. Formaldehyde-detoxifying role of the tetrahydromethanopterin-linked pathway in Methylobacterium extorquens AM1. J. Bacteriol. 1857160-7168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marx, C. J., M. Laukel, J. A. Vorholt, and M. E. Lidstrom. 2003. Purification of the formate-tetrahydrofolate ligase from Methylobacterium extorquens AM1 and demonstration of its requirement for methylotrophic growth. J. Bacteriol. 1857169-7175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marx, C. J., and M. E. Lidstrom. 2004. Development of an insertional expression vector system for Methylobacterium extorquens AM1 and generation of null mutants lacking mtdA and/or fch. Microbiology 1509-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marx, C. J., S. J. Van Dien, and M. E. Lidstrom. 2005. Flux analysis uncovers key role of functional redundancy in formaldehyde metabolism. PLoS Biol. 3e16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nemecek-Marshall, M., R. C. MacDonald, J. J. Franzen, C. L. Wojciechowski, and R. Fall. 1995. Methanol emission from leaves (enzymatic detection of gas-phase methanol and relation of methanol fluxes to stomatal conductance and leaf development). Plant Physiol. 1081359-1368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nesmeyanova, M. A. 2000. Polyphosphates and enzymes of polyphosphate metabolism in Escherichia coli. Biochemistry (Moscow) 65309-314. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pomper, B. K., O. Saurel, A. Milon, and J. A. Vorholt. 2002. Generation of formate by the formyltransferase/hydrolase complex (Fhc) from Methylobacterium extorquens AM1. FEBS Lett. 523133-137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pomper, B. K., and J. A. Vorholt. 2001. Characterization of the formyltransferase from Methylobacterium extorquens AM1. Eur. J. Biochem. 2684769-4775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pomper, B. K., J. A. Vorholt, L. Chistoserdova, M. E. Lidstrom, and R. K. Thauer. 1999. A methenyl tetrahydromethanopterin cyclohydrolase and a methenyl tetrahydrofolate cyclohydrolase in Methylobacterium extorquens AM1. Eur. J. Biochem. 261475-480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Quayle, J. R. 1963. The assimilation of 1-C compounds. J. Gen. Microbiol. 32163-166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Segel, I. H. 1975. Enzyme kinetics: behavior and analysis of rapid equilibrium and steady-state enzyme systems. Wiley Interscience, New York, NY.

- 35.Sy, A., A. C. J. Timmers, C. Knief, and J. A. Vorholt. 2005. Methylotrophic metabolism is advantageous for Methylobacterium extorquens during colonization of Medicago truncatula under competitive conditions. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 717245-7252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Van Dien, S. J., and M. E. Lidstrom. 2002. Stoichiometric model for evaluating the metabolic capabilities of the facultative methylotroph Methylobacterium extorquens AM1, with application to reconstruction of C-3 and C-4 metabolism. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 78296-312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Van Dien, S. J., T. Strovas, and M. E. Lidstrom. 2003. Quantification of central metabolic fluxes in the facultative methylotroph Methylobacterium extorquens AM1 using C-13-label tracing and mass spectrometry. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 8445-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vorholt, J. A. 2002. Cofactor-dependent pathways of formaldehyde oxidation in methylotrophic bacteria. Arch. Microbiol. 178239-249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vorholt, J. A., L. Chistoserdova, M. E. Lidstrom, and R. K. Thauer. 1998. The NADP-dependent methylene tetrahydromethanopterin dehydrogenase in Methylobacterium extorquens AM1. J. Bacteriol. 1805351-5356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vorholt, J. A., C. J. Marx, M. E. Lidstrom, and R. K. Thauer. 2000. Novel formaldehyde-activating enzyme in Methylobacterium extorquens AM1 required for growth on methanol. J. Bacteriol. 1826645-6650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zakrzewski, S. F. 1966. Evidence for the chemical interaction between 2-mercaptoethanol and tetrahydrofolate. J. Biol. Chem. 2412957-2961. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]