Abstract

Biotin-containing 3-methylcrotonyl coenzyme A (MC-CoA) carboxylase (MCCase) and geranyl-CoA (G-CoA) carboxylase (GCCase) from Pseudomonas aeruginosa were expressed as His-tagged recombinant proteins in Escherichia coli. Both native and recombinant MCCase and GCCase showed pH and temperature optima of 8.5 and 37°C. The apparent K0.5 (affinity constant for non-Michaelis-Menten kinetics behavior) values of MCCase for MC-CoA, ATP, and bicarbonate were 9.8 μM, 13 μM, and 0.8 μM, respectively. MCCase activity showed sigmoidal kinetics for all the substrates and did not carboxylate G-CoA. In contrast, GCCase catalyzed the carboxylation of both G-CoA and MC-CoA. GCCase also showed sigmoidal kinetic behavior for G-CoA and bicarbonate but showed Michaelis-Menten kinetics for MC-CoA and the cosubstrate ATP. The apparent K0.5 values of GCCase were 8.8 μM and 1.2 μM for G-CoA and bicarbonate, respectively, and the apparent Km values of GCCase were 10 μM for ATP and 14 μM for MC-CoA. The catalytic efficiencies of GCCase for G-CoA and MC-CoA were 56 and 22, respectively, indicating that G-CoA is preferred over MC-CoA as a substrate. The enzymatic properties of GCCase suggest that it may substitute for MCCase in leucine catabolism and that both the MCCase and GCCase enzymes play important roles in the leucine and acyclic terpene catabolic pathways.

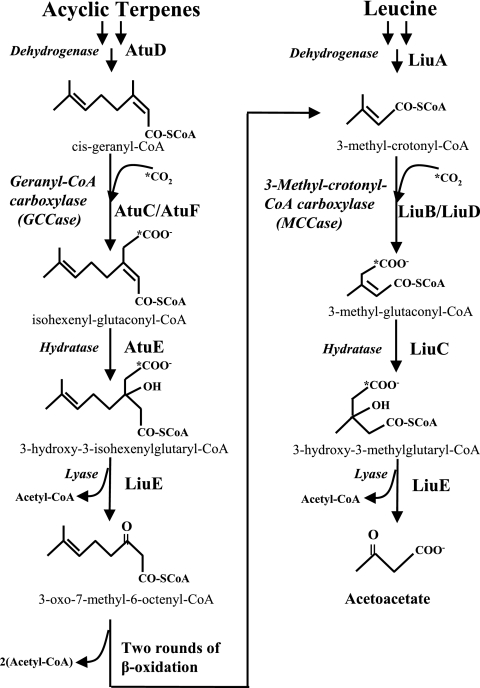

In the corresponding bacterial catabolic pathways, terpenes are converted to cis-geranyl coenzyme A (G-CoA) and leucine-isovalerate is converted to isovaleryl-CoA. After four analogous reactions that are common to both pathways, the final products of terpene degradation are acetyl-CoA and 3-oxo-7-methyl-6-octenoyl-CoA, and those of leucine catabolism are acetyl-CoA and acetoacetate (Fig. 1). After two β-oxidation cycles, 3-oxo-7-methyl-6-octenoyl-CoA yields 3-methylcrotonyl-CoA (MC-CoA), an intermediary of the leucine-isovalerate pathway (Fig. 1). Therefore, the acyclic terpene utilization and leucine-isovalerate pathways converge in the MC-CoA intermediate (1, 10). Two homologous gene clusters that encode the enzymes of the acyclic terpene (atuABCDEFGH, for acyclic terpenes utilization) and leucine-isovalerate (liuRABCDE, for leucine-isovalerate utilization) catabolic routes have been recently identified in Pseudomonas aeruginosa (1, 6, 10, 16) and Pseudomonas citronellolis (11). Phylogenetic analysis of the P. aeruginosa AtuF α subunit of G-CoA carboxylase (GCCase) suggested that it originated by a horizontal transfer event from alphaproteobacteria to P. aeruginosa and may implicate different functions (1).

FIG. 1.

Participation of GCCase and MCCase in the acyclic monoterpene and leucine catabolic pathways of P. aeruginosa PAO1 (1, 10). AtuD, citronellyl-CoA dehydrogenase; AtuC/AtuF, GCCase; AtuE, isohexenylglutaconyl-CoA hydratase; LiuA, isovaleryl-CoA dehydrogenase; LiuB/LiuD, MCCase; LiuC, 3-methylglutaconyl-CoA hydratase; LiuE, 3-hydroxy-3-methyl-glutaryl-CoA (also proposed as 3-hydroxy-3-isohexenylglutaryl-CoA lyase).

Key enzymes in both pathways are GCCase, encoded by the atuC/atuF genes, and MC-CoA carboxylase (MCCase), encoded by the liuB/liuD genes (Fig. 1). These enzymes are composed of two subunits, i.e., LiuB and AtuC (β subunits) and LiuD and AtuF (α subunits), of their respective MCCase and GCCase enzymes (1, 10, 16). MCCase and GCCase enzymes show two main domains, the acyl-CoA-binding and the carboxybiotin-binding domains, which are implicated in the transfer of a carboxyl group to the acyl-CoA substrate (17). On the other hand, both LiuD and AtuF (α subunits) show four highly conserved domains in the acyl-CoA carboxylases: (i) the ATP-binding site (GGGGKGM), (ii) a CO2 fixation domain (RDCS), (iii) the catalytic site of the biotin-dependent carboxylase family (EMNTR), and (iv) a biotin-carboxyl carrier domain (AMKM).

It has been suggested that the P. citronellolis GCCase carboxylates both G-CoA and MC-CoA, while MCCase carboxylates only MC-CoA (9, 13, 15). Although the genes that encode the enzymes of the acyclic terpene and leucine/isovalerate catabolic pathways in P. aeruginosa and P. citronellolis have been recently elucidated (1, 10), there is still uncertainty regarding the bifunctionality of the carboxylases involved. Using an indirect method for GCCase and MCCase activity determination (a coupled reaction with pyruvate kinase and lactate dehydrogenase), Förster-Fromme et al. (10) suggested that both GCCase and MCCase showed specific activities for their substrates G-CoA and MC-CoA, respectively. However, data from our group suggest that the two catabolic pathways may share gene products or that some enzymes could show a bifunctional activity (1).

This work was focused on the biochemical characterization of MCCase and GCCase and on elucidation of whether these enzymes can use both MC-CoA and G-CoA as substrates.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and culture conditions.

The bacterial strains used in this work are Escherichia coli TOP10 (Invitrogen), E. coli BL21 (22), E. coli JM101 (22), and P. aeruginosa PAO1SM (25). Plasmids used were pGEM-T Easy (Promega), pTrc His2A and -C (Invitrogen), and pCDFDuet-1 (Novagen). The strains were grown at 30°C in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium or in M9 minimal medium (22). Solid media were prepared by adding 1.5% agar. Strains were grown on M9 minimal medium supplemented with 0.075% citronellol (Merck) as the sole carbon and energy source. The growth of strains on branched-chain amino acids was tested as described previously (20), using 0.3% (wt/vol) l-leucine supplemented with l-valine and l-isoleucine at 0.005% each (obtained from Sigma and Merck Co.). Antibiotics used were streptomycin at 200 μg/ml and ampicillin at 100 μg/ml.

DNA manipulation and cloning of the atu and liu genes.

Genomic and plasmid DNA extraction, restriction enzyme digestion, and agarose gel electrophoresis were carried out by standard methods (22). P. aeruginosa genomic DNA was used as the template for PCR amplification. For liuD gene amplification the oligonucleotide LiuD1 was used to introduce a 5′ BamHI restriction site upstream of the start codon, and LiuD2 was used to introduce a HindIII restriction site at the 3′ end of liuD. For liuB, atuC, and atuF the amplification strategy was the same, using the oligonucleotides LiuB1 and LiuB2, AtuC1 and AtuC2, and AtuF1 and AtuF2. The atuF gene was also amplified using the oligonucleotides AtuF3, introducing a BglII site, and AtuF4, introducing a KpnI site (see Table S1 in the supplemental material).

PCR amplification was carried out using Platinum Pfx DNA polymerase (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's recommendations. Amplified DNA fragments were cloned into the pGem-T Easy vector, giving plasmids pGliuB, pGliuD, pGatuF, and pGatuC with the cloned liuB, liuD, atuF, and atuC genes, respectively. Recombinant plasmids were subjected to double digestion at the respective enzyme sites designed in the oligonucleotides described above, and the DNA fragments for the liuB, liuD, and atuC genes were subcloned into the pTrcHis2A plasmid, while the atuF gene was subcloned into the pTrcHis2C plasmid, giving the pTrc-liuB, pTrc-liuD, pTrc-atuC, and pTrc-atuF plasmids. Additionally, the atuC and atuF genes were amplified with the AtuC1-AtuC2 and AtuF3-AtuF4 oligonucleotides, respectively; the resulting fragments were cloned into pGem-T Easy and subcloned into the pCDFDuet-1 coexpression vector, giving the pCFC3-atuFC plasmid. The recombinant plasmids were transferred to electrocompetent E. coli JM101 cells and analyzed by digestion with restriction endonucleases and by DNA sequencing.

Expression, purification, and enzyme reconstitution of recombinant proteins.

The plasmids containing the atu/liu genes were transferred to E. coli strain TOP10 or BL21, the cells were cultured on LB medium (400 ml), expression was induced with IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside) (0.1 mM), and the cells were incubated for an additional 4 h at 37°C with shaking. Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 5,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C. The bacterial pellet was suspended in 10 ml of buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4) and disrupted by sonication at 4°C. The proteins were purified from crude extracts according to the His-bind purification kit protocol (Novagen). The resin-protein mixture was washed twice with 1× wash buffer, and the protein was eluted using 1 ml of elution buffer containing 100 mM imidazole.

Reconstitution of MCCase and GCCase was carried out using the subunits purified as described above and denaturing with 6 M urea. The α and β subunits (2 mg each) were mixed and renatured by dialysis using a Spectrum 10-kDa-molecular-mass-cutoff (Fisher Scientific) membrane in a buffer containing 20 mM K2HPO4, 20% glycerol, and 0.75 mM dithiothreitol (pH 8.0) for 1 h at 4°C, changing the buffer (100 ml) six times.

G-CoA synthesis.

G-CoA was synthesized by the mixed anhydride method of Hajra and Bishop (14). Geranic acid (Sigma-Aldrich) (770 μmol) was dried twice with 500 μl of benzene under a gentle N2 stream; the same molar amount of butylated hydroxytoluene dissolved in benzene was added, and 400 μl of oxalyl chloride and 800 μl of benzene were added and flushed with N2. The mixture was then incubated at 36°C in a water bath for 1 h, dried under a stream of N2, washed with 400 μl of benzene, and dried. CoA (29 μmol) was dissolved in 400 μl of 0.125 mM NH4HCO3 in water adjusted to pH 8.8 with NH4OH and 0.8 ml of tetrahydrofuran. The mixture was stirred at 36°C in a water bath for 30 min. The reaction was stopped with 20 μl 20% HClO4, and the products were dried under an N2 gas stream. The residue was dissolved in 100 μl 2% HClO4, and the mixture was lyophilized. The lyophilized G-CoA was dissolved in water, and its concentration was determined by the hydroxamate method (19).

Determination of MCCase and GCCase activities.

Cultures of the P. aeruginosa PAO1 strain were grown with shaking at 30°C in 50 ml of M9 medium with 0.075% of citronellol or 0.3% of leucine as a carbon source for 48 h. Cells were harvested by centrifugation and washed with 50 ml of 100 mM K2HPO4, pH 8.0. Pellets were suspended in 5 ml of the same buffer, disrupted by sonication, and centrifuged for 10 min to 15,000 × g at 4°C to eliminate undisrupted cells and cell debris. The protein content was determined by the Bradford method as described previously (22). Purification of MCCase and GCCase from P. aeruginosa crude extracts was carried out using avidin-agarose resin (Sigma), with equilibration with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (pH 7.4) with 1 mg/ml of biotin; the crude extract was added to the resin and incubated for 2 h at 4°C, the mixture was washed with PBS, and biotinylated proteins were eluted with PBS containing 2 mM biotin. MCCase and GCCase activities in the extracts or in purified fractions were measured by the incorporation of radioactivity from 14CO2 into acid-stable, nonvolatile material as previously described (15, 21). The reaction mixture contained 20 mM K2HPO4 (pH 8.5), 10 mM MgCl2, cell extract (300 μg of protein) or 40 μg of purified protein, ATP either at 5 mM or in the range of 0 to 40 mM, NaH14CO3 (specific activity, 1.96 GBq/mmol [53 mCi/mmol]; Amersham) either at 10 mM or in the range of 0 to 10 mM, and 3-MC-CoA (Sigma) or cis-G-CoA (synthesized as described above) either at 100 μM or in the range of 0 to 100 μM, in a total reaction volume of 100 μl. The reaction was started by the addition of NaH14CO3 (prepared as 1:10 NaH14CO3-NaHCO3 to 10 mM), and the mixture was incubated at 37°C for 10 min. The reaction was stopped by adding 200 μl of 6 M HCl, the contents of the tube were evaporated to dryness at 90°C, and the residue was suspended in 100 μl of distilled water. Radioactivity was quantified using a liquid scintillation counter (Hewlett-Packard 1600 TR). Nonspecific 14CO2 fixation was assayed in the absence of substrate. Specific activity was calculated as dpm of 14CO2 fixed/0.53 μmol·min−1·mg−1 of protein.

Western blot analysis.

Pseudomonas aeruginosa cell extract samples containing 100 μg of protein or 10 μg of purified proteins were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) (10% polyacrylamide) and electrophoretically transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Amersham Biosciences). MCCase and GCCase α subunits (LiuD and AtuF proteins) were detected by using the avidin-horseradish peroxidase (HRP) conjugate (Bio-Rad) as previously described (1). MCCase and GCCase β subunits (LiuB and AtuC) were detected using polyclonal mouse antibodies. Antibodies were obtained from a polyclonal serum after immunization of mice with LiuB or AtuC recombinant protein expressed from the pTrc-liuB and pTrc-atuC plasmids and purified from the cell extracts as described above. The polyclonal serum was obtained at the Iowa State University Hybridoma Facility (www.biotech.iastate.edu/service_facilities/hybridoma.html). The membranes were probed using the polyclonal serum, and the anti-mouse-HRP conjugate was used as the second antibody (donkey anti-mouse immunoglobulin G-HRP; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.) as indicated by the provider. HRP color development was carried out using 4-chloro-1-naphthol (Sigma) and H2O2.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Characterization of MCCase and GCCase from P. aeruginosa grown on leucine and citronellol.

Previous data from our group suggested that MCCase and GCCase show catalytic activity with both MC-CoA and G-CoA substrates, indicating a possible bifunctional role of these enzymes in both the leucine/isovalerate and acyclic terpene catabolic pathways (1). In this work we found that MCCase or GCCase can be coexpressed from cultures of P. aeruginosa but that it was difficult to discriminate whether the enzymes showed bifunctionality over both G-CoA and MC-CoA substrates (1). Similar results were found for P. citronellolis (9, 15).

To test whether the native properties of MCCase are conserved after heterologous expression of the recombinant enzyme, the MCCase was also purified and characterized as isolated from its native host, P. aeruginosa. As indicated in previous reports, MCCase is induced when P. aeruginosa grows on leucine as the sole carbon and energy source (1, 16); thus, MCCase was purified by from P. aeruginosa cells grown on leucine. With the purified fraction, the optimal pH and temperature for MCCase activity were 8.5 and 37°C, respectively (data not shown). With increasing concentrations of the MC-CoA substrate, a sigmoidal kinetics of MCCase activity was observed (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). The kinetic constants for MCCase using MC-CoA as the substrate are a K0.5 of 9.2 μM and a Vmax of 425 nmol/min·mg of protein. Under this condition the MCCase enzyme did not carboxylate the analogous substrate, GC-CoA, indicating that MCCase from P. aeruginosa specifically recognizes MC-CoA as its substrate and therefore does not possess GCCase activity (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). This is consistent with the behavior of P. citronellolis MCCase, which is specific for the MC-CoA substrate and has no detectable GCCase activity (8), as also found in pea leaf and potato mitochondria (2). A difference between the MCCases of P. aeruginosa and P. citronellolis is the apparent fivefold-higher affinity for the MC-CoA substrate (K0.5s of 9.2 μM and 43 μM, respectively). On the other hand, when P. aeruginosa was grown on citronellol as the sole carbon source, both the MCCase and GCCase enzymes were expressed (data not shown). Under these conditions MCCase and GCCase were detected and the enzymatic activities displayed similar behavior with both substrates, showing typical sigmoidal behavior with similar kinetic constants (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). The kinetic parameters for MCCase and GCCase activities were K0.5s of 8.84 and 8.80 μM and Vmaxs of 591 and 627 nmol/min·mg of protein for MC-CoA and G-CoA, respectively. As mentioned above, the purification method used did not differentiate between GCCase and MCCase activities, and therefore it was not possible to elucidate whether GCCase also carboxylates MC-CoA. In addition, these data suggest that GCCase may be nonspecific in its ability to carboxylate G-CoA and MC-CoA or that under the conditions used a subunit exchange mechanism between MCCase and GCCase may possibly contribute to a nonspecific carboxylase enzyme. This behavior could explain why atuC and atuF mutants are affected in their ability to grow on leucine and why an atuF mutant regains the ability to grow on leucine when it is transformed with the liu cluster (1). Therefore, we decided to carry out the characterization of both enzymes by expressing them in E. coli, a bacterium that does not possess the MCCase and GCCase enzymes.

Expression of the MCCase and GCCase from P. aeruginosa in E. coli.

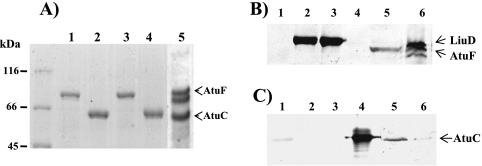

The individual enzyme subunits were expressed in E. coli and recovered efficiently, obtaining preparations that were >90% pure (Fig. 2A, lanes 1 to 4). In SDS-PAGE the proteins showed relative molecular masses for the LiuD, LiuB, AtuF, and AtuC subunits of 78, 63, 74, and 63 kDa, respectively (Fig. 2A). The expressed and purified LiuB-His and LiuD-His subunits of MCCase did not support enzyme activity. Several attempts to restore the activity of this enzyme using different renaturation conditions were conducted, without success. However, when the purified α and β subunits were combined, denatured, and then renatured as described above, the active MCCase enzyme was recovered. This result shows that incorporation of a His tag does not disturb the function of MCCase, and therefore this recombinant MCCase enzyme was used for the kinetic characterization as described below. In contrast, this strategy was not successful in generating a functional GCCase enzyme. However, a functional GCCase enzyme was successfully reconstituted when the AtuC and AtuF subunit genes were coexpressed and copurified as described above. The coexpressed AtuF-S protein was found to bind to the AtuC-His subunit and was also copurified (Fig. 2). A similar behavior was observed during the expression of the AccD1-His subunit of acetyl-CoA carboxylase from Corynebacterium glutamicum (12) and the acyl-CoA carboxylase from Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) (5).

FIG. 2.

Electrophoretic analysis of the recombinant heterologous expression of P. aeruginosa MCCase and GCCase subunits. (A) Coomassie blue-stained SDS-PAGE analysis of assembled gels of recombinant proteins expressed in E. coli and purified using affinity chromatography. Lanes: 1, AtuF-His; 2, AtuC-His; 3, LiuD-His; 4, LiuB-His expressed from pTrcHis-2A vector; and 5, AtuC-His/AtuF-S expressed from pCDFDuet-1 coexpression vector. Molecular mass makers are shown on the left; the protein bands corresponding to AtuC/AtuF are indicated with arrowheads. (B) Western blot analysis of purified recombinant proteins probed with avidin-HRP conjugate to detect biotin-containing proteins. Lanes: 1, LiuB-His; 2, LiuD-His; 3, AtuF-His; 4, AtuC-His; 5, AtuC-His/AtuF-S; and 6, extract from PAO1 culture grown on citronellol. (C) Western blot analysis of purified recombinant proteins probed first with anti-AtuC-His polyclonal antibody and then with anti-mouse-HRP as a secondary antibody. Lanes are the same as in panel B.

SDS-PAGE analysis of this purified fraction indicated that it contained three major protein bands (Fig. 2A, lane 5). Western blotting analysis with avidin-HRP conjugate showed that the upper band (74 kDa) was a biotinylated protein, and because it corresponded in molecular mass to the biotinylated subunit of the GCCase purified from P. aeruginosa extracts grown on citronellol (Fig. 2B, lanes 5 and 6, respectively), we identified this as the recombinant biotinylated AtuF subunit of the GCCase. Similar Western blot analyses with polyclonal anti-AtuC antiserum identified the lowest band (63 kDa) as the recombinant AtuC subunit, corresponding to the GCCase β subunit; the molecular mass of this band is similar to that of the AtuC subunit purified from P. aeruginosa extracts grown on citronellol (Fig. 2C, lanes 5 and 6, respectively). Although only a faint signal was identified in the purified LiuB protein sample with the anti-AtuC serum (Fig. 2C, lane 1), it was clear from the difference in signal intensity that this is a cross-reactivity of the antiserum. These results established that after coexpression of the AtuC-His and AtuF-S proteins in E. coli, the GCCase complex was reconstituted, and therefore this complex was used for kinetics characterization. It was found that for both the recombinant MCCase and GCCase enzymes, the optimal pH and temperature were 8.5 and 37°C, respectively (data not shown). These values were identical to those for the native host enzymes and similar to those reported for MCCases from mammalian (18), bacterial (23), and plant (2, 3, 4, 7) sources. Like MCCase from P. citronellolis, MCCase and GCCase from P. aeruginosa are inactivated by temperatures higher than 50°C (15) (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material), in contrast to MCCases from pea leaves and potato mitochondria, which are stable above that temperature (2).

Kinetic parameters of recombinant MCCase.

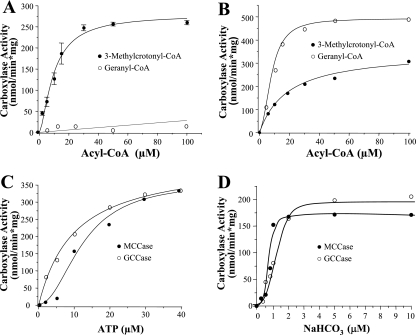

The dependence of MCCase activity on substrates was tested at the optimal conditions, pH 8.5 and 37°C. A typical sigmoidal behavior was observed with respect to MC-CoA, while no activity was observed when G-CoA was assayed as the substrate (Fig. 3A). In kinetics calculations the values were adjusted to Hill's equation, showing a correlation coefficient of 0.99 with a Hill's coefficient of 2.3, which suggested that the enzyme has an oligomeric conformation and could provoke cooperative effects of the substrate. The kinetic constants of this enzyme for MC-CoA were a K0.5 of 9.8 μM and a Vmax of 279 nmol/min·mg of protein; these values are in agreement with values obtained with the MCCase purified from of the native host, P. aeruginosa. The catalytic efficiencies (Vmax/Km) of the two enzyme preparations also were similar (46 and 56, respectively), indicating that the recombinant proteins and the heterologous expression did not affect MCCase functionality, as occurs in other carboxylases (5, 12). On the other hand, the kinetic dependence on the ATP and NaHCO3 substrates showed a sigmoidal response, suggesting an allosteric regulation of MCCase by ATP and NaHCO3 (Fig. 3C and D). The apparent kinetic parameters for ATP were a K0.5 of 13 μM and a Vmax of 356 nmol/min·mg of protein, and those for NaHCO3 were a K0.5 of 0.8 μM and a Vmax of 178 nmol/min·mg of protein. We conclude, therefore, that the MCCase from P. aeruginosa is specific for the MC-CoA substrate.

FIG. 3.

Kinetic behavior of recombinantly produced P. aeruginosa MCCase and GCCase enzymes. (A and B) Carboxylase activities of recombinant LiuB/LiuD (A) and AtuC/AtuF (B) proteins, purified and reconstituted as described in Materials and Methods. (C and D) ATP (C) and bicarbonate (D) concentration dependence of the MCCase and GCCase activities. Data given are the average of three determinations; standard deviations of the given values are shown in panel A, and the averages of two determinations with variations of less than 5% of the given values are shown in panels B, C, and D.

Kinetic parameters of recombinant GCCase.

Kinetic parameters for the heterologously coexpressed AtuC/AtuF proteins were also measured at optimal conditions (pH 8.5 and 37°C). Under these conditions, the AtuC/AtuF complex catalyzed both GCCase and MCCase enzymatic activities. In relation to the G-CoA substrate, this enzyme exhibited sigmoidal kinetics, adjusting to Hill's equation with coefficient of 2.2, but in relation to the MC-CoA substrate, it exhibited Michaelis-Menten kinetics (Fig. 3B). These results indicate that the AtuC/AtuF enzyme is able to utilize both G-CoA and MC-CoA as substrates. The kinetic constants with G-CoA were a K0.5 of 8.8 μM and a Vmax of 492 nmol/min·mg of protein, and those with MC-CoA were a Km of 14 μM and a Vmax of 308 nmol/min·mg of protein. The catalytic efficiencies for the AtuC/AtuF enzyme were 56 for G-CoA carboxylation and 22 for MC-CoA carboxylation. These results indicate that the AtuC/AtuF enzyme prefers G-CoA over MC-CoA as a substrate, and therefore should be considered a GCCase enzyme. In P. citronellolis it has been observed that GCCase is able to carboxylate 5 to 15 different acyl-CoA substrates, including MC-CoA (8). An interesting fact is that the plant GCCase shows a strict substrate preference, carboxylating G-CoA but not MC-CoA (13). This finding suggests that in P. aeruginosa GCCase may play a bifunctional role during its participation in both the acyclic terpene and the leucine catabolic pathways. Using G-CoA as the carboxylation substrate, the dependence of enzymatic activity on ATP and NaHCO3 was also tested. In relation to ATP a typical Michaelis-Menten kinetics was observed (Fig. 3C), whereas with NaHCO3 a sigmoidal kinetics was observed (Fig. 3D). The kinetic parameters of GCCase for ATP were a Km of 10 μM and a Vmax of 423 nmol/min·mg of protein, and those for NaHCO3 were a K0.5 of 1.2 μM and a Vmax of 210 nmol/min·mg of protein.

The kinetic parameters of both MCCase and GCCase with the cosubstrates ATP and NaHCO3 followed similar tendencies, as could be expected because they have common cosubstrates.

This is the first report showing that MCCase and GCCase display sigmoidal kinetic behavior for their substrates and cosubstrates. These results are interesting because most of the MCCases characterized to date show typical Michaelis-Menten kinetics against their substrates. A sigmoidal kinetic behavior would indicate that the active site is modified by the binding of each substrate, increasing the affinity for the next one, and/or that the binding of substrate promote the oligomerization of the enzyme subunits, favoring their activity. A precedent that supports this finding may be found with pyruvate carboxylase and the MCCases from pea leaf and potato mitochondria, in which the domain arrangement provides a mechanism for allosteric activation (24) and sigmoidal behavior with respect to Mg2+ variations (2, 3).

In conclusion, our results indicate that MCCase, encoded by liuB/liuD genes, specifically recognizes MC-CoA as its substrate, and the bifunctionality of the GCCase suggests that it may supplant the MCCase function in leucine catabolism and therefore that both the MCCase and GCCase enzymes might play important roles in the catabolic pathways for leucine as well as for acyclic terpenes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the Pseudomonas Genome Community Annotation Project for use of the updated database.

This research was funded by grants CONACYT (P-46547-Z), C.I.C.-UMSNH 2.14, and COECyT CB070229-2 to J.C.-G and MCB-0416730 from the National Science Foundation to B.J.N. J.A.A. was supported by a fellowship from CONACyT, and C.D.-P. was supported by UMSNH.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 9 May 2008.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://jb.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aguilar, J. A., A. N. Zavala, C. Díaz-Pérez, C. Cervantes, A. L. Díaz-Pérez, and J. Campos-García. 2006. The atu and liu clusters are involved in the catabolic pathways for acyclic monoterpenes and leucine in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 722070-2079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alban, C., P. Baldet, S. Axiotis, and R. Douce. 1993. Purification and characterization of 3-methylcrotonyl-coenzyme A carboxylase from higher plant mitochondria. Plant Physiol. 102957-965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baldet, P., C. Alban, S. Axiotis, and R. Douce. 1992. Characterization of biotin and 3-methylcrotonyl-coenzyme A carboxylase in higher plant mitochondria. Plant Physiol. 99450-455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen, Y., E. S. Wurtele, X. Wang, and B. J. Nikolau. 1993. Purification and characterization of 3-methylcrotonyl-CoA carboxylase from somatic embryos of Daucus carota. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 305103-109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Diacovich, L., S. Peiru, D. Kurth, E. Rodriguez, F. Podesta, C. Khosla, and H. Gramajo. 2002. Kinetic and structural analysis of the new group of acyl-CoA carboxylases found in Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2). J. Biol. Chem. 27731228-31236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Díaz-Pérez, A. L., N. A. Zavala-Hernández, C. Cervantes, and J. Campos-García. 2004. The gnyRDBHAL cluster is involved in acyclic isopreoid degradation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 705102-5110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Diez, T. A., E. S. Wurtele, E. S., and B. J. Nikolau. 1994. Purification and characterization of 3-methylcrotonyl-coenzyme-A carboxylase from leaves of Zea mays. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 31064-75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fall, R. R. 1981. 3-Methyl-crotonyl-CoA and geranyl-CoA carboxylases from Pseudomonas citronellolis. Methods Enzymol. 71791-799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fall, R. R., and M. L. Hector. 1977. Acyl-coenzyme A carboxylases. Homologous 3-methylcrotonyl-CoA and geranyl-CoA carboxylases from Pseudomonas citronellolis. Biochemistry 164000-4005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Förster-Fromme, K., B. Höschle, C. Mack, M. W. Armbruster, and D. Jendrossek. 2006. Identification of genes and proteins necessary for catabolism of acyclic terpenes and leucine/isovalerate in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 724819-4828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Förster-Fromme, K., and D. Jendrossek. 2006. Identification and characterization of the acyclic terpene utilization gene cluster of Pseudomonas citronellolis. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 264220-225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gande, R., L. G. Dover, K. Krumbach, G. S. Besra, H. Sahm, T. Oikawa, and L. Eggeling. 2007. The two carboxylases of Corynebacterium glutamicum essential for fatty acid and mycolic acid synthesis. J. Bacteriol. 1895257-5264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guan, X., T. Diez, T. K. Prasad, B. J. Nikolau, and E. S. Wurtele. 1999. Geranoyl-CoA carboxylase: a novel biotin-containing enzyme in plants. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 36212-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hajra, A. K., and J. E. Bishop. 1986. Preparation of radioactive acyl coenzyme A. Methods Enzymol. 12250-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hector, M. L., and R. R. Fall. 1976. Multiple acyl-coenzyme A carboxylases in Pseudomonas citronellolis. Biochemistry 153465-3472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hoschle, B., V. Gnau, and D. Jendrossek. 2005. Methylcrotonyl-CoA and geranyl-CoA carboxylases are involved in leucine/isovalerate utilization (Liu) and acyclic terpene utilization (Atu), and are encoded by liuB/liuD and atuC/atuF, in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Microbiology 1513649-3656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kimura, Y., R. Miyake, Y. Tokumasu, and M. Sato. 2000. Molecular cloning and characterization of two genes for the biotin carboxylase and carboxyltransferase subunits of acetyl coenzyme A carboxylase in Myxococcus xanthus. J. Bacteriol. 1825462-5469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lau, E. P., B. C. Cochran, and R. R. Fall. 1980. Isolation of 3-methylcrotonyl-coenzyme A carboxylase from bovine kidney. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 205352-359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lipmann, F., and L. C. Tuttle. 1945. A specific micromethod for the determination of acyl phosphates. J. Biol. Chem. 15921-28. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Martin, R. R., V. D. Marshall, J. R. Sokatch, and L. Unger. 1973. Common enzymes of branched-chain amino acid catabolism in Pseudomonas putida. J. Bacteriol. 115198-204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rodríguez, E., and H. Gramajo. 1999. Genetic and biochemical characterization of the alpha and beta components of a propionyl-CoA carboxylase complex of Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2). Microbiology 1453109-3119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sambrook, J., and D. W. Russell. 2001. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 3rd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 23.Schiele, U., and F. Lynen. 1981. 3-Methylcrotonyl-CoA carboxylase from Achromobacter. Methods Enzymol. 71781-791. [Google Scholar]

- 24.St. Maurice, M., L. Reinhardt, K. H. Surinya, P. V. Attwood, J. C. Wallace, W. W. Cleland, and I. Rayment. 2007. Domain architecture of pyruvate carboxylase, a biotin-dependent multifunctional enzyme. Science 3171076-1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wong, S. M., and J. J. Mekalanos. 2000. Genetic footprinting with mariner-based transposition in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 9710191-10196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.