Abstract

During membrane fusion, the influenza A virus hemagglutinin (HA) adopts an extended helical structure that contains the viral transmembrane and fusion peptide domains at the same end of the molecule. The peptide segments that link the end of this rod-like structure to the membrane-associating domains are approximately 10 amino acids in each case, and their structure at the pH of fusion is currently unknown. Here, we examine mutant HAs and influenza viruses containing such HAs to determine whether these peptide linkers are subject to specific length requirements for the proper folding of native HA and for membrane fusion function. Using pairwise deletions and insertions, we show that the region flanking the fusion peptide appears to be important for the folding of the native HA structure but that mutant proteins with small insertions can be expressed on the cell surface and are functional for membrane fusion. HA mutants with deletions of up to 10 residues and insertions of as many as 12 amino acids were generated for the peptide linker to the viral transmembrane domain, and all folded properly and were expressed on the cell surface. For these mutants, it was possible to designate length restrictions for efficient membrane fusion, as functional activity was observed only for mutants containing linkers with insertions or deletions of eight residues or less. The linker peptide mutants are discussed with respect to requirements for the folding of native HAs and length restrictions for membrane fusion activity.

Enveloped viruses enter cells following fusion of the viral and host cell membranes. A diverse collection of viral fusion proteins (VFPs) has evolved to carry out this function, and these VFPs have now been segregated into three classes based on an assortment of different properties (18, 39). VFPs of all classes have a common requirement for structural rearrangements in order to mediate membrane fusion. These conformational changes can be brought about by a variety of external stimuli that include acidification, receptor binding, association with a separate viral receptor binding protein, or interaction with a coreceptor. In most cases, such conformational changes result in the relocation of relatively hydrophobic “fusion peptide” domains to allow for their interaction with the cellular membranes. This functions to bridge the gap between viral and cellular membranes, and in conjunction with VFP conformational changes, the membranes are brought together to initiate the fusion process. However, even among viral fusion proteins of the same class, a number of structural and mechanistic features distinguish the manner in which the membrane fusion is accomplished.

Influenza A viruses are enveloped viruses that enter host cells via the endocytic pathway, and membrane fusion function for these viruses is mediated by the hemagglutinin (HA) glycoprotein, a class I VFP. HA-mediated fusion is initiated by the acidification of endosomes, which triggers irreversible conformational changes that convert the molecule from the metastable structure that is present on the surface of infectious viruses to a highly thermostable rod-shaped form of the trimeric protein (5). During this process, a conserved fusion peptide domain from each monomer is extruded from the interior of the molecule and directed toward the host membrane. Associated HA structural changes draw the HA transmembrane domain to the same end of the helical rod-like molecule as the fusion peptide. This feature is shared by all class I VFPs, whose members include the fusion proteins of retroviruses, paramyxoviruses, and Ebola virus (12, 31), which all adopt extremely stable alpha-helical rod-like structures subsequent to the fusion-inducing conformational changes. All of these VFPs contain a central trimeric coiled-coil core structure formed by interacting helices from each of the monomers. The fusion peptide domains reside at the N-terminal end of each helix of the central core either as a direct extension of the coiled coil or linked by a small peptide sequence. At the C-terminal end of the central core, structural elements lead to an inversion of the polypeptide chain, which then traces antiparallel and packs against the coiled coil, resulting in a rod-like structure. The transmembrane domains of the fusion proteins are located C terminal to the antiparallel polypeptide chain, placing them at the same end of the structure as the fusion peptide. Presumably, the close approximation of the two membrane-associating domains of the protein in this energetically stable conformational state is an important feature for the fusion process.

For some of the class I VFP rod structures, exemplified by some of the retrovirus and paramyxovirus fusion proteins, the antiparallel C-terminal polypeptide chains that pack against the coiled coil are mostly helical, and the overall structures are commonly referred to as six-helix bundles (1, 38, 44). In these bundles, the outer helices associate tightly with the core helices, and it is thought that this is energetically advantageous for bringing about the juxtaposition of the two membranes. For human immunodeficiency virus gp41, there is evidence that the transition into six-helix bundles may provide the energy to induce membrane fusion (25), and this feature of six-helix bundle formation is relevant for the use of antiviral peptide compounds designed to mimic the outer helices to block membrane fusion (17, 19, 29, 40, 43). For influenza virus HA, the antiparallel polypeptides exist as extended chains that pack into the grooves between the core helices. In the case of HA, the membrane-proximal ends of the rod structures appear to be held together in part due to an unusual N-cap structure that terminates the core helices (9).

For the class I VFPs, our understanding of how the juxtaposition of membranes leads to fusion is hindered by the lack of information on the structure of the membrane-associating domains and, in many cases, the peptide linkers that connect such domains with ectodomain fragments of known structure. For influenza virus HA, the linkers that connect the rod-like low-pH HA to the fusion peptide and the transmembrane domain are each approximately 10 amino acids in length, and our current knowledge suggests that these linkers may adopt extended conformations (9). Previous reports demonstrated little effect on fusion for short deletions and substitution mutations in the C-terminal linker region, but those studies using expressed HAs were focused principally on the adjacent region involved in the formation of the N cap (4, 28). Little has been done to comprehensively address the length requirements of these connecting regions in order for membrane fusion to take place. The determination of possible constraints for fusion activity dictated by linker length may aid in the understanding of how fusion is mediated by HA and other VFPs. Here, we use both expressed HAs and viruses generated by reverse genetics to analyze mutant HAs containing peptide sequences of differing lengths for the regions linking the HA ectodomain to either the transmembrane domain or the fusion peptide domain. We show that to maintain fusion function, such sequences can tolerate relatively small deviations in length but that length constraints do indeed exist for this process.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells.

HeLa, Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK), 293T, CV1, and BHK21 cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 4 mM glutamine, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin. Ten percent fetal calf serum was utilized for HeLa, MDCK, and 293T cells, and 5% fetal calf serum was used for CV1 and BHK21 cells.

Construction of plasmids.

The wild-type (WT) A/Aichi/2/68 virus HA gene was cloned into pRB21 using PstI and NcoI sites (3) for protein expression and functional studies. The sequences of the entire coding regions were verified. To make the serial deletion and insert constructs, the recombinant PCR or site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) was utilized with mutated primers (primer sequences are available upon request). To reduce the possibility of introducing unexpected mutations due to PCR, the protocol for the site-directed mutagenesis kit was modified. Briefly, PCRs using Pfu Turbo were performed, followed by DpnI digestion of the parent plasmid. DH5α cells were transformed and cultured in LB broth supplemented with 100 μg/ml of ampicillin, and plasmids were purified. The plasmids were digested with NdeI-AgeI or AgeI-NcoI, and the fragment containing the expected mutants were subcloned into WT HA pRB21 cDNA digested with the same enzymes. PCR-amplified regions were then sequenced. Recombinant vaccinia viruses were generated according to a method developed previously by Blasco and Moss (3). HA-expressing recombinant viruses were plaque purified twice, followed by the generation of stock viruses in CV1 cells. Trypsin cleavage experiments for the analysis of protein expression were carried out as described previously (13). Cell surface expression as well as conformational change assays were analyzed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) using vaccinia virus-infected HA-expressing HeLa cells as described previously (20, 32).

Membrane fusion assays.

Polykaryon formation assays were carried out using recombinant vaccinia virus-infected BHK21 cells as described previously (32). Briefly, recombinant vaccinia virus-infected HA-expressing cell monolayers were treated with 5 μg/ml tosylsulfonyl phenylalanyl chloromethyl ketone (TPCK)-trypsin (Sigma) for 10 min to cleave HA0 into HA1 and HA2, and the pH was adjusted to 5.0 (or incubated at neutral pH) for 1 min using a buffer with 10 mM HEPES, 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM CaCl2, and 20 mM citrate. Cells were then washed with phosphate-buffered saline, incubated in complete medium at 37°C, and monitored for polykaryon formation by light microscopy. At 30 min, cells were fixed with 0.25% glutaraldehyde and stained with 1% toluidine blue.

Labeling of HRBCs with R18 and calcein-AM.

Fresh heparinized human erythrocytes (HRBCs) were colabeled with the membrane probe octadecyl rhodamine B chloride (R18) and the aqueous dye calcein-AM (Sigma) as described previously (35). Ten milliliters of freshly prepared HRBCs (1% in Dulbecco's phosphate-buffered saline [DPBS]) was mixed with 10 μl of R18 (2 mM in ethanol) with vigorous shaking. The mixture was incubated in the dark for 30 min at room temperature, followed by the addition of 30 ml of 7.5% fetal bovine serum (FBS)-Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) for 20 min at room temperature to remove unbound R18. The R18-labeled HRBCs were washed three times and resuspended in DPBS (4% R18-labeled HRBCs). A 10-μl aliquot of 4 mM calcein-AM in dimethyl sulfoxide was added to 1 ml of 4% R18-labeled HRBCs in the dark and incubated at 37°C for 1 h, followed by the addition of 30 ml of 7.5% FBS-DMEM for 20 min at room temperature, three washes with DPBS to remove unbound calcein, and resuspension in DMEM (0.02% HRBCs).

Dye transfer assay.

To analyze hemifusion and fusion pore formation by WT HA and HA mutants, an R18 and calcein transfer assay was performed. Recombinant vaccinia virus-infected HeLa cells expressing HA were pretreated with neuraminidase (NA) (30 mU/ml; Sigma) at 37°C for 60 min, washed once with DPBS, and treated with TPCK-trypsin (5 μg/ml) at 37°C for 5 min. Cells were washed with soybean trypsin inhibitor (5 μg/ml), washed, and incubated with R18- and calcein-labeled HRBCs at room temperature for 30 min for hemadsorption. After unbound HRBCs were removed by three washes, the cells were washed and incubated for 1 min at 37°C in low-pH buffer (10 mM HEPES, 20 mM sodium citrate [pH 5.0], 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM CaCl2, and 20 mM raffinose to prevent colloidal-osmotic swelling of the erythrocytes that could be induced by HA-mediated leakage) (24). The medium was replaced with DMEM supplemented with 7.5% FBS. After incubation for 15 min at 37°C, hemadsorption and the transfer of fluorescence were observed with a phase-contrast microscope and a fluorescence microscope, respectively. Photographs of three microscopic fields selected at random were taken. On average, 100 cells were screened per culture dish.

Reverse genetics.

The mutated HA genes were introduced into the RNA expression plasmid pPolI Aichi HA, and the gene segment sequences were verified entirely. Infectious influenza viruses were then generated from plasmid cDNAs (26). Briefly, Human 293T cells were transfected with the 17 protein and RNA expression plasmids using Superfect (Qiagen) transfection reagents according to the supplier's guidelines. At 3 days posttransfection, the viruses in the cell supernatants were passaged and titrated on MDCK cells. The viruses generated were H3N1 viruses containing the Aichi virus HA and other gene segments derived from A/WSN/33 virus.

Virus passages in MDCK cells.

The rescued viruses were diluted in serum-free DMEM for low-multiplicity passages. MDCK cells were washed and absorbed by the diluted viruses, followed by the incubation in serum-free DMEM supplemented with 2.5 μg/ml TPCK-trypsin. When the clear cytoplasmic effect was observed in 2 to 7 days, depending on mutant viruses, the viruses in the second lowest diluted well were harvested and used for the next passage as described above. The virus stocks were then titrated on MDCK cells at intermediate stages and following six passages in MDCK cells. For titration experiments, plaques were visualized by immunostaining to detect small plaques as well as infectious centers (13).

Genetic stability of viruses.

To confirm the genetic stability of the HA gene sequences of the rescued viruses after six passages in MDCK cells, the viral RNAs were purified using a viral RNA Miniprep kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Reverse transcriptase PCR was performed using a Stratagene kit according to the manufacturer's manual, and PCR products were sequenced.

RESULTS

Design of the mutant HAs.

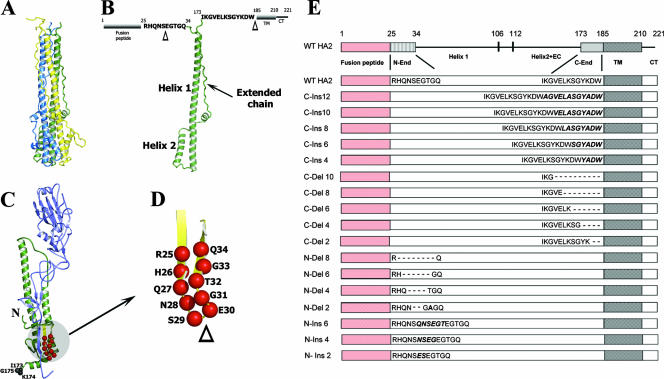

At the pH of membrane fusion, HA undergoes a number of structural rearrangements, which include the detrimerization of HA1 head domains, the extrusion of fusion peptide domains from a buried position in the molecular structure, the extension of the central coiled coil due to helix formation by an extended-chain peptide segment on neutral-pH HA2 sequences, and a helix-to-loop transition of coiled-coil residues that results in the 180° reorientation of residues C terminal to HA2 position 111 (2, 5). The structures of the HA2 subunits at the pH of fusion were initially derived from proteolytic fragments of bromelain-solubilized viral HA ectodomains (BHA) following low-pH treatment and digestion with thermolysin. Thermolysin solubilizes low-pH aggregates of HA due to the removal of fusion peptide residues by digestion at HA2 residue 38 (30), resulting in the product referred to as TBHA2. The expression of HA2 ectodomain residues 23 through 185 using Escherichia coli at a neutral pH (EHA2) yields a structure that is superimposable with TBHA2 but which contains all HA2 ectodomain residues between the fusion peptide and the viral transmembrane domain (9). The structure of the EHA2 trimer is shown in Fig. 1A, and Fig. 1B depicts a single monomer and sites of attachment of the linker peptide domains to the low-pH structure. The EHA2 structure shows that the N terminus of the low-pH rod structure contains an unusual N cap composed of residues 34, 35, 36, and 37, which terminates the helices as the peptide chains cross laterally to interact with residues of the neighboring monomer. No electron density was observed for residues 23 through 33, suggesting that the peptide chain linking the low-pH rod to the fusion peptide may not have a defined structure. The peptide chain at the C-terminal portion of EBHA2 traces along the groove of the coiled coil until it encounters the N-cap structure, with which it forms several hydrogen bonds. The electron density for the C terminus of EHA2 extends to residue 178 and suggests that the peptide regions linking the low-pH rods to the viral transmembrane domain are likely to be flexible in solution. Therefore, we were optimistic that manipulation of the length of the peptide-linking regions at both the N-terminal end and the C-terminal end should be feasible without altering functionally important structural entities of the low-pH HA.

FIG. 1.

Ribbon diagrams of low-pH HA (top) and neutral-pH HA (bottom). (A) Structure of the rod-shaped low-pH HA trimer, with individual monomers shown in yellow, blue, and green. The viral and host membranes would be located at the top of this structure, as represented. (B) Individual HA2 polypeptide monomer in the same orientation as the green polypeptide from A. Helix 1, helix 2, and the extended chain are labeled. The amino acid sequences of the linker domains are positioned at their respective locations of attachment to the low-pH structure, and the sequence alignments with respect to the fusion peptide and transmembrane domains are shown. The triangles indicate positions at which deletions and insertions were constructed, as detailed at the left (A). (C) Locations of the linker region residues as they reside in the neutral-pH HA. Residues 173, 174, and 175 at the C-terminal end of BHA are labeled, and the locations of residues that become the N-end linker following acidification are shown as red balls within the yellow antiparallel β-sheets. N indicates the location of the fusion peptide. (D) Region of β-structure in larger scale to identify the locations of residues involved in deletion mutants and the locations at which inserted pairs of amino acids were made. (E) Constructs used in this study. At the top is a linear representation of the WT HA2 subunit from the N-terminal fusion peptide (red) through to the C-terminal cytoplasmic tail (CT). The numbers at the top indicate the amino acid positions of HA2. The label N-end indicates the linker between the fusion peptide and helix 1, which is the long central helix that forms the central coiled coil in the low-pH structure. Residues between residues 106 and 112 form a loop in low-pH HA that inverts the polypeptide chain by 180° to locate the fusion peptide and transmembrane domains at the same end of the structure. Helix 2+EC denotes the antiparallel helix and extended chain that trace along the central coiled coil back in the direction of the membrane-associating domains. C-end indicates the linker domain between the trimeric core structure extended-chain region and the transmembrane domain (labeled TM). The nomenclature and sequence details of the mutants analyzed in the N-end and C-end linker regions are represented below the WT representation (these are not to scale).

On the other hand, manipulation of the residues that compose the linking peptides in the context of the neutral-pH structure of HA was potentially more problematic. A prerequisite for the functional analysis of these peptide linker regions is the requirement that they be capable of folding into a cell surface-expressed metastable conformation that can be subsequently triggered by acidification to execute the obligate structural transitions. This was more straightforward for the peptide sequences linked to the transmembrane domain, as we had previous experience manipulating this region for expressing HA mutants with protease recognition sequences for generating the soluble uncleaved HA precursor for structure determination (8). Included among the mutants analyzed for the HA precursor study was an insertion of 14 residues derived from collagen, which folded and expressed properly and served as a useful reference point for the present studies. Mutagenesis of the sequences that form the linker to the fusion peptide domain presented different challenges. The amino acids of interest, HA2 residues 24 to 33, are components of antiparallel β-sheet structure in native HA that are located on the trimer exterior between the fusion peptide and the viral membrane (41), as shown in Fig. 1C. In efforts to minimize the disruption of the neutral-pH HA structure, our mutagenesis strategy for this region involved pairwise deletions and insertions in multiples of 2 from the point where the β-structure reverses in an antiparallel direction at the membrane-proximal end (Fig. 1D).

Figure 1E summarizes the mutations that were generated in diagrammatic form. Deletions in the peptide sequence linking the C-terminal end of the HA2 rod structure to the transmembrane domain (C-del mutations) were made in multiples of 2 in the N-terminal direction starting from HA2 residue 185 at the junction of the transmembrane domain. Insertions in this region (C-ins mutations) were made by incremental duplications of the linking sequences from HA2 residue 185. Basic residues in the duplicated sequences were changed to alanine to mitigate against protease digestion. For the peptide linking the trimeric core of low-pH HA to the fusion peptide, pairwise deletions (N-del mutations) and insertions (N-ins mutations) were made from the end of the β-structure as described above. By coincidence, the deletion of the two residues of the turn region would generate a potential glycosylation signal (N28/G31/T32), so for the two-residue deletion mutant N-del 2, an additional threonine-to-alanine substitution was incorporated at HA2 position 32. Likewise, for the N-ins 2 mutant, the dipeptide Glu-Ser rather than Ser-Glu was inserted to avoid the generation of a glycosylation recognition sequence.

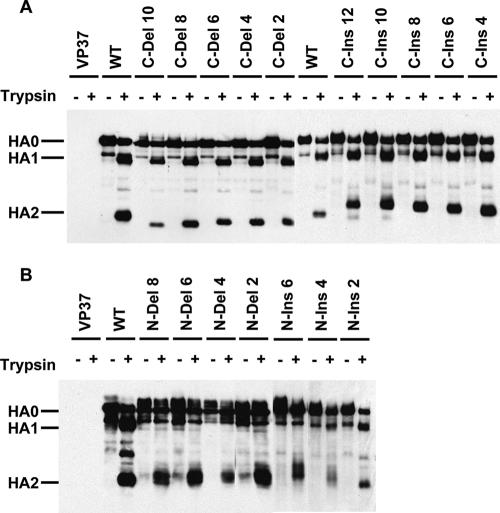

Analysis of HA cell surface expression by trypsin cleavage.

Recombinant vaccinia viruses were generated for the expression of mutant HAs, and the constructs that were examined are shown in Fig. 1E. The WT HA of A/Aichi/2/68 virus used in these studies contains a single arginine at the HA1-HA2 cleavage site, so it is expressed on the surface of recombinant vaccinia virus-infected cells in the uncleaved HA0 precursor form. Cleavage is required to prime HA for fusion activity. Trypsin treatment of HA-expressing cell monolayers cleaves HA0 into the disulfide-linked subunits HA1 and HA2 and provides an assay for surface expression. For the mutants analyzed in this study, the migration patterns of trypsin cleavage products following sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) under reducing conditions are useful for verifying the sizes of HA2 insertion and deletion mutants and, in some cases, provide clues regarding structural anomalies of expressed HAs. Figure 2 shows the results of Western blot analyses of cell lysates processed following the incubation of HA-expressing cell monolayers with or without trypsin. For WT HA and all C-end mutants, we observed that treatment with trypsin generates polypeptide cleavage products corresponding to HA1 and HA2 (Fig. 2A). The migration patterns for the HA2 subunit are indicative of the appropriate-sized inserted or deleted segments. These results suggest that the C-end mutants are transported to the cell surface and can be proteolytically activated for fusion potential by cleavage into HA1 and HA2.

FIG. 2.

Cell surface expression of HAs as assayed by trypsin cleavage of HA0 into HA1 and HA2. Recombinant vaccinia virus-infected HA-expressing cell monolayers were incubated with or without trypsin, and cell lysates were analyzed by Western blotting following SDS-PAGE under reducing conditions. Lanes labeled VP37 are nonrecombinant vaccinia virus-infected cell controls.

The results for the N-end mutants are not as straightforward (Fig. 2B). The appearance of HA2 bands for all mutants suggests that they are capable of transport to the cell surface. However, to various degrees, most of the mutant HAs display aberrant trypsin cleavage properties. For several mutants, the HA2 bands are diffuse or migrate as doublets. In addition, the unequivocal generation of appropriately sized HA1 subunits is observed only for N-ins 2 and, to a lesser degree, N-ins 4. These results suggest that deletions and insertions in the β-structure comprised by HA2 residues 25 to 34 result in structural alterations in HA0 and/or cleaved, neutral-pH HA. The extent of the structural disparities for N-end mutants is not sufficient to abrogate transport to the cell surface, but they appear for most mutants to be capable of affecting the susceptibility of residues that comprise the HA1 subunit to trypsin.

Analysis of mutant HAs by antibody reactivity.

Transport to the cell surface and folding of mutant HAs into the native conformation were also assessed by ELISA using an anti-HA rabbit polyclonal serum and a panel of monoclonal antibodies that react with different regions of HA in a conformation-specific fashion. Antibodies HC3, HC100, HC31, and HC68 are known to bind to at least three distinct sites on the HA membrane-distal head domains based on the locations of HA substitutions present in neutralization-resistant virus mutants (15) and by studies on HA-antibody complexes using electron microscopy (42) and X-ray crystallography (2, 16). Of these antibodies, HC3 and HC100 bind to separate epitopes that do not change in structure following the conformational changes that take place during membrane fusion. On the other hand, HC31 and HC68 bind to an antigenic region at the membrane-distal trimer interface, which is lost as a result of acid-induced structural rearrangements. Table 1 summarizes the ELISA data obtained for antibody reactivity to recombinant vaccinia virus-infected HA-expressing HeLa cell monolayers. The data are presented as percentages of optical densities at 450 nm (OD450s) from ELISA results in relation to WT HA (100%). The rabbit polyclonal serum was observed to react well with all mutants, confirming that they are capable of being transported to the cell surface. Monoclonal antibodies HC3 and HC100 displayed binding patterns similar to that of the rabbit polyclonal serum. For the C-end mutations, the reactivity data with HC31 and HC68 are indicative of correctly folded HAs; however, these antibodies clearly distinguish structural differences among the N-end mutant HAs. All N-del mutants were observed to react poorly to both HC31 and HC68, as was the N-ins 6 mutant. The N-ins 2 HA was shown to react well with these antibodies, whereas reactivity to N-ins 4 HA appeared to be partially reduced. Overall, the data for antibody reactivity are in agreement with the trypsin digestion data presented above. These data suggest that all mutants can express on the cell surface and that the C-end mutants are structurally comparable to WT HA as determined by these criteria. The data indicate that with the exception of N-ins 2 and N-ins 4, the N-end mutant HAs are expressed in conformations that are clearly distinguishable from that of WT HA.

TABLE 1.

Antibody binding to expressed HAs by ELISA

| HA | % OD450b

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R-anti-HAa | HC3 | HC100 | HC31 | HC68 | |

| WT | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| C-Del 10 | 124 | 98 | 82 | 103 | 76 |

| C-Del 8 | 97 | 90 | 85 | 118 | 97 |

| C-Del 6 | 93 | 125 | 101 | 124 | 131 |

| C-Del 4 | 114 | 108 | 109 | 175 | 92 |

| C-Del 2 | 122 | 119 | 109 | 167 | 105 |

| C-Ins 12 | 125 | 115 | 113 | 184 | 109 |

| C-Ins 10 | 91 | 86 | 84 | 86 | 51 |

| C-Ins 8 | 110 | 112 | 115 | 150 | 112 |

| C-Ins 6 | 126 | 115 | 122 | 154 | 115 |

| C-Ins 4 | 105 | 109 | 106 | 119 | 99 |

| N-Del 8 | 92 | 91 | 85 | 25 | 6 |

| N-Del 6 | 98 | 89 | 84 | 13 | 5 |

| N-Del 4 | 86 | 88 | 79 | 33 | 7 |

| N-Del 2 | 117 | 110 | 105 | 27 | 6 |

| N-Ins 6 | 103 | 74 | 76 | 34 | 32 |

| N-Ins 4 | 119 | 106 | 115 | 68 | 57 |

| N-Ins 2 | 124 | 111 | 103 | 134 | 127 |

R-anti-HA, rabbit anti-HA polyclonal serum.

Values are expressed as percentages of ELISA readings of the OD450 relative to the WT (100%).

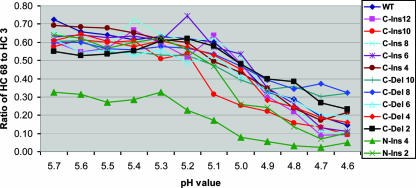

Examination of acid-induced conformational changes.

Antibodies HC31 and HC68 specifically recognize the neutral-pH HA (they react poorly to the low-pH conformation). This makes them useful reagents for monitoring acid-induced conformational changes and the pH at which these changes take place. As noted above, HC3 reacts well with both the neutral- and low-pH structures. For all mutant HAs that were recognized by HC68 in the experiments described above, we used ELISA to measure and compare the reactivities of HC68 and HC3 as a function of pH. The HC68-to-HC3 ratios are shown in Table 2 and are plotted in graph form in Fig. 3. The data demonstrate that all of the C-end mutants are capable of undergoing the conformational changes required for membrane fusion and that, in each case, such transitions were found to take place at approximately the same pHs as those of WT HA. For the N-end mutants, only the N-ins 2 and N-ins 4 HAs showed significant reactivity to HC68 at a neutral pH. These mutants were both found to undergo the conformational changes with characteristics similar to those of WT HA. The other N-end mutants reacted poorly to neutral-pH-specific antibodies and were not amenable to analysis using this assay.

TABLE 2.

Conformational change assay based on the ratio of HC68 to HC3 reactivity

| HA | HC68/HC3 OD450 ratio at pHa:

|

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5.7 | 5.6 | 5.5 | 5.4 | 5.3 | 5.2 | 5.1 | 5 | 4.9 | 4.8 | 4.7 | 4.6 | |

| WT | 0.725 | 0.657 | 0.640 | 0.614 | 0.633 | 0.620 | 0.603 | 0.477 | 0.326 | 0.288 | 0.191 | 0.144 |

| C-Ins12 | 0.603 | 0.546 | 0.568 | 0.665 | 0.592 | 0.518 | 0.637 | 0.483 | 0.303 | 0.219 | 0.089 | 0.093 |

| C-Ins10 | 0.575 | 0.614 | 0.599 | 0.609 | 0.508 | 0.538 | 0.313 | 0.253 | 0.221 | 0.157 | 0.133 | 0.092 |

| C-Ins 8 | 0.658 | 0.600 | 0.567 | 0.723 | 0.644 | 0.608 | 0.619 | 0.520 | 0.320 | 0.238 | 0.111 | 0.103 |

| C-Ins 6 | 0.628 | 0.640 | 0.625 | 0.634 | 0.608 | 0.745 | 0.572 | 0.535 | 0.349 | 0.262 | 0.130 | 0.112 |

| C-Ins 4 | 0.693 | 0.685 | 0.677 | 0.650 | 0.616 | 0.598 | 0.495 | 0.433 | 0.346 | 0.239 | 0.171 | 0.216 |

| C-Del 10 | 0.604 | 0.607 | 0.545 | 0.546 | 0.529 | 0.527 | 0.473 | 0.393 | 0.341 | 0.359 | 0.304 | 0.320 |

| C-Del 8 | 0.599 | 0.600 | 0.565 | 0.558 | 0.575 | 0.567 | 0.536 | 0.467 | 0.394 | 0.342 | 0.372 | 0.324 |

| C-Del 6 | 0.616 | 0.545 | 0.556 | 0.528 | 0.555 | 0.488 | 0.523 | 0.413 | 0.332 | 0.282 | 0.201 | 0.195 |

| C-Del 4 | 0.609 | 0.645 | 0.604 | 0.575 | 0.608 | 0.573 | 0.530 | 0.450 | 0.282 | 0.245 | 0.187 | 0.161 |

| C-Del 2 | 0.549 | 0.525 | 0.537 | 0.553 | 0.609 | 0.620 | 0.578 | 0.479 | 0.399 | 0.385 | 0.267 | 0.233 |

| N-Ins 4 | 0.326 | 0.314 | 0.270 | 0.286 | 0.326 | 0.228 | 0.172 | 0.079 | 0.057 | 0.033 | 0.024 | 0.051 |

| N-Ins 2 | 0.640 | 0.623 | 0.568 | 0.598 | 0.622 | 0.560 | 0.469 | 0.259 | 0.242 | 0.138 | 0.069 | 0.102 |

Values represent ratios of ELISA readings of the OD450s for the ratio of HC68 to HC3 monoclonal antibodies.

FIG. 3.

Graphs of ELISA data showing the pHs of conformational change for various mutant and WT HAs. Graphs plot the ratios of HC68 to HC3 reactivity as a function of pH. HC68 binds well with neutral-pH HA but poorly to the low-pH structure. HC3 binds equally well with both HA conformations.

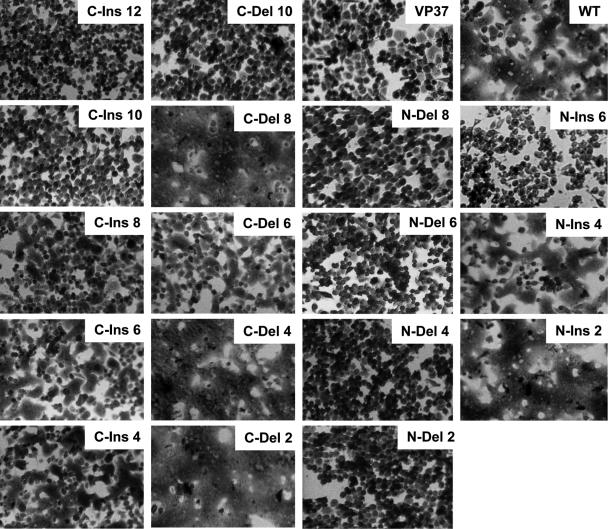

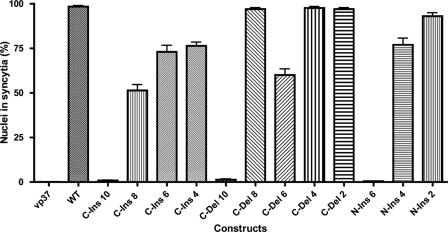

Fusion activity of HA mutants determined by polykaryon formation.

The capacity of mutant HAs to mediate membrane fusion was examined using an assay for polykaryon formation by HA-expressing cells. Monolayers of BHK21 cells infected with recombinant vaccinia viruses were treated with trypsin to cleave HA into HA1 and HA2, incubated at pH 5.0, neutralized, incubated in complete medium, and monitored by light microscopy for polykaryon formation. Figure 4 shows representative results for this assay, indicating that for the C-end mutations, fusion activity can be observed for both deletion and insertion mutants of up to 8 amino acids but not for mutations involving 10 or more residues. The efficiency of polykaryon formation was evaluated based on the percentage of nuclei within syncytia and is shown in Fig. 5. All C-end mutants displayed expression and folding characteristics similar to those of WT HA and were capable of undergoing acid-induced conformational changes. Therefore, the length requirements defined for fusion by this assay are likely to relate directly to distance or structural constraints imposed at the latter stages of the fusion process. As expected, all N-end HA mutants that were incapable of undergoing acid-induced conformational changes were negative for fusion activity. Polykaryons were detected only for the N-end mutants that could be cleaved at the cell surface and undergo structural rearrangements at low pH, N-ins 2 and N-ins 4. For the C-ins mutants, the efficiency of polykaryon formation decreased incrementally as the length of the insertions increased, and polykaryon formation dropped off dramatically to an undetectable level when the length was increased from 8 to 10 residues. Similarly, for the C-del mutants, fusion efficiency was dramatically inhibited when 10 rather than 8 residues were deleted. Furthermore, analysis of the pH at which polykaryons were formed showed that all fusion-positive mutants mediate fusion at a pH similar to that of WT HA (data not shown), reflecting the results obtained for the pH of conformational change as determined by ELISA.

FIG. 4.

Polykaryon formation by HA-expressing BHK cells following incubation at pH 5.0.

FIG. 5.

Efficiency of polykaryon formation of WT and mutant HAs. The efficiency of polykaryon formation was estimated by the percentage of nuclei located within syncytia. For WT HA and some of the mutants, this value approached 100%. The means and standard deviations from five independent experiments were determined.

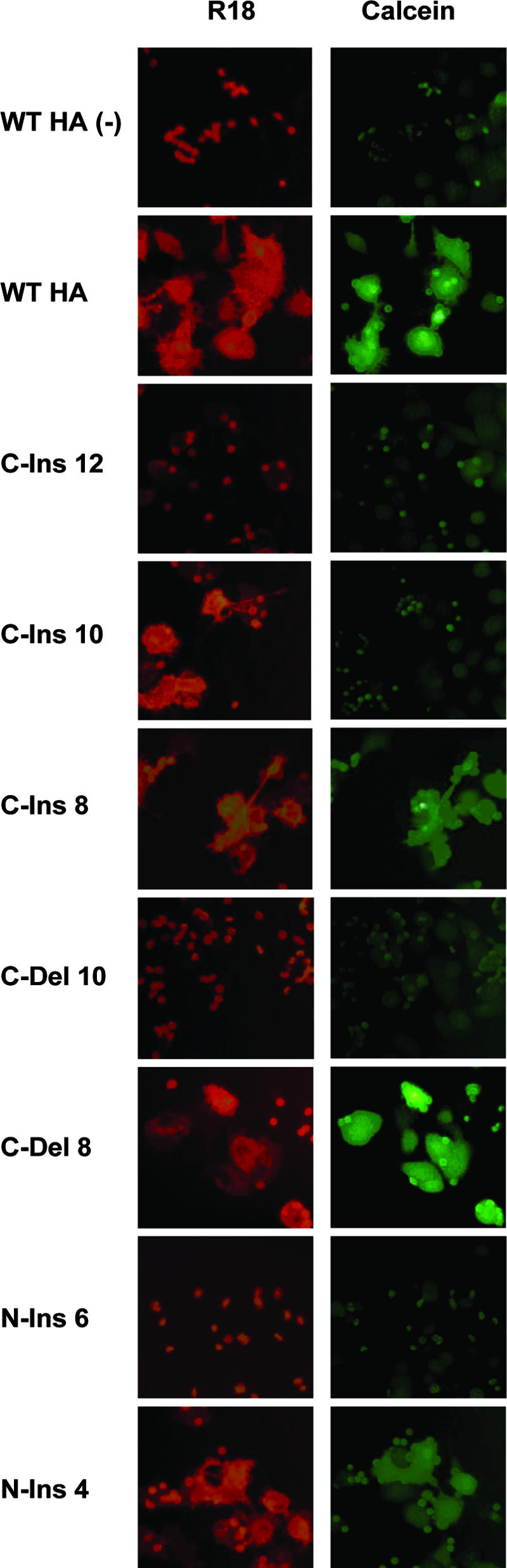

Transfer of lipophilic and aqueous dyes mediated by mutant HAs.

We also analyzed the capacities of our mutant HAs to mediate the transfer of the lipophilic probe R18 and the small soluble aqueous dye calcein from erythrocytes to HA-expressing cell monolayers. Human erythrocytes were labeled with R18 and calcein, adsorbed to HA-expressing cell monolayers, and incubated at either neutral pH or pH 5.0. Figure 6 shows that both R18 and calcein can be transferred into cells expressing HAs with insertions or deletions of as many as eight residues in the C-terminal linker region and for N-end insertions of up to four residues, confirming the full fusion results obtained with the polykaryon formation assays. Interestingly, the C-ins 10 mutant was able to transfer only the lipophilic R18 probe, indicating a hemifusion phenotype. The C-ins 12 mutant displayed no fusion function. As such, this appears to define a length requirement for pore formation that is slightly less than that required for lipid mixing.

FIG. 6.

Hemifusion and full fusion activities of HA mutants. Human erythrocytes loaded with R18 and calcein were adsorbed to HA-expressing cells and exposed to acidic pH to monitor HA-mediated transfer of R18 (lipid mixing) or the soluble dye calcein (content mixing). WT HA (−), WT HA that has not been treated with trypsin to cleave HA0 into HA1 and HA2.

Incorporation of mutant HAs into infectious viruses and analysis of their replication characteristics.

In a further set of experiments, attempts were made to incorporate WT and mutant HA genes into infectious influenza viruses using a plasmid-based reverse genetics system (26). For the C-end insertion mutants, viruses were generated with all HAs that displayed fusion activity in the polykaryon formation assays. For the C-end deletion mutants, only those with two- and four-residue deletions were rescued, even though fusion function could be demonstrated for HAs with further deletions of six and eight amino acids. For the N-end mutants, only the N-ins 2 HA was incorporated into virions. This was not surprising, as this was the only N-end HA that displayed characteristics similar to those of WT HA in all of the assays described above. In total, six of the linker-length mutants were rescued as infectious viruses, five with mutations at the C-terminal end and one with a two-residue insertion into the N-terminal linker peptide. All C-end mutant viruses were severely attenuated in MDCK cells, displaying viral titers 3 to 5 orders of magnitude lower than those of the WT based on plaque assays (Table 3). Interestingly, the only N-end mutant that was found to incorporate into infectious viruses, N-ins 2, displayed viral titers that were reduced only twofold relative to those of WT.

TABLE 3.

Virus titers of mutant influenza virus and sequence changes following serial passages

| Virus | Virus titer at passage 6 (PFU/ml) | Sequence change(s) at passage 6 in:

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| HA1 | HA2 | ||

| WT | 1.0 × 107 | L226P | |

| C-Ins 8 | 1.0 × 102 | R216K | |

| C-Ins 6 | 6.0 × 103 | R124G, 9 aa to Ga | |

| C-Ins 4 | 2.0 × 102 | ||

| C-Del 4 | 7.5 × 103 | F3L, R124K | |

| C-Del 2 | 5.0 × 102 | I45T | |

| N-Ins 2 | 5.0 × 106 | I6M | |

HA2 residues 177 to 185 (ELKSGYKDW) were changed to one glycine; therefore, Ins 6 became Del 2 overall. aa, amino acids.

Genetic stability of mutant HAs.

Viruses were passaged serially at low multiplicities to assess the genetic stabilities of the linker mutations. Following six passages, the consensus sequences of the entire HA of virus populations were determined. Mutations were detected for all except the C-ins 4 HA, but most of these mutations were located in the coding sequences for HA residues outside of the mutated linker peptide regions (Table 3). The locations of these mutations indicate that most of them were probably selected for the elevated pH of fusion, as we have observed previously with mutants generated by reverse genetics (22). These mutants are discussed below. The most intriguing mutation observed occurred in the peptide linker sequence of the C-ins 6 mutant. This contained a deletion, which essentially converted HA2 residues 177 to 185, ELKSGYKDW, into a single glycine residue. Therefore, the HA with a six-residue insertion was converted into a two-residue deletion. The deletion actually did not occur directly in the inserted sequences but precisely adjacent to them at the N-terminal junction with WT amino acid sequences.

DISCUSSION

A panel of insertion and deletion mutants was generated in the polypeptide sequences that link the helical rod-like component of low-pH HA to the domains that associate with viral and cellular membranes during fusion. The mutants were analyzed for cell surface expression, folding, the capacity to undergo acid-induced conformational changes, and membrane fusion function. Furthermore, their capacities to incorporate into infectious influenza viruses were assessed, as were their replication properties and genetic stabilities. Overall, the results indicate that the lengths of these sequences are likely to be conserved in HAs for functional purposes.

For the N-end mutations included in our analyses, the peptide sequences appear to be critical for proper folding into the native precursor and/or neutral-pH HA structures (8, 41). Based on antibody reactivity, trypsin cleavage properties of expressed HAs, and the capacity to mediate polykaryon formation, only the two-residue insertion mutant, N-ins 2, appeared to be structurally and functionally comparable to the WT. The N-ins 4 mutant displayed an intermediate phenotype based on the properties of its expressed HA. Relatively weak HA1 and diffuse HA2 bands were observed for this mutant by SDS-PAGE following trypsin treatment, and it showed reduced reactivity to neutral-pH-specific monoclonal antibodies compared to that of WT HA. Polykaryon formation by expressed N-ins 4 HA was reproducibly detectable but at levels that were visibly lower than those of the WT or N-ins 2 HAs. Among the N-end mutants, only the N-ins 2 HA was rescued as a component of an infectious influenza virus. Interestingly, among all viruses rescued in the present study, N-ins 2 was the only one that replicated to levels comparable to those of the WT. Overall, the N-end mutants reveal more regarding the requirements of these residues for the folding of HA into its neutral-pH structure than regarding the length requirements of the N-end-linking peptide for fusion following acidification. The residues addressed here are components of an antiparallel β-sheet in the structures of precursor and cleaved neutral-pH HAs and pack against residues from the HA1 polypeptide chain (Fig. 1C and D). Although we made logical attempts to manipulate the insertion and deletion mutations based on structural considerations, most mutations were expressed on cell surfaces in conformations that were distinguishable from that of WT HA. Sequence analysis of the HAs of different subtypes shows that this region is completely conserved in length and contains several positions that are either invariant or highly conserved (27). Taken together with our results, this suggests that this antiparallel β-sheet provides an important structural role for the folding of native HA. Therefore, attempts to determine length requirements for the fusion of this domain may require alternative approaches. Among such alternatives, numerous versions of expressed HA2 polypeptide constructs have been generated and shown to fold into a structure that is indistinguishable from that assumed by native HA following acid-induced conformational changes (9-11, 33). However, we and others have been unable to faithfully reproduce fusion with such HA2 polypeptides using numerous constructs, expression strategies, and approaches designed to optimally generate available N-terminal fusion peptides for association with target membranes. Presumably, this is due to the inability to deliver the fusion peptide to the proper membrane target location without prior aggregation or association with the “wrong” membrane or because free-energy changes or structural intermediates that accompany the transition from the native to the low-pH conformation are required for fusion. Thus, we may be limited to approaches such as those presented here for analyzing the N-end peptide linker region and, as such, must contend with problems involving the folding of native, neutral-pH HA mutants.

On the other hand, the insertion and deletion mutations to the linker polypeptide domain at the C-terminal end of low-pH HA2 were relatively straightforward to analyze. We show that insertion mutations containing as many as 12 residues and mutant HAs with deletions of up to 10 amino acids can express on the cell surface in conformations that resemble those of the WT protein. This range of mutants allowed us to define functional limits to the number of residues that could be inserted or deleted while still maintaining fusion activity. The results show that HAs with deletions or insertions of up to 8 residues, but not 10, are competent for mediating polykaryon formation. All mutants that were capable of causing polykaryon formation were also observed to mediate content mixing in the dye transfer experiments. The results indicate that deletions of eight residues or less are functional, consistent with results described previously by Park et al. (28), who showed that the deletion mutants Δ176-180 and Δ181-184 were able to mediate both lipid and content mixing in dye transfer experiments similar to ours. Of the mutants that were negative for polykaryon formation, only C-ins 10 caused the transfer of R18, indicating a hemifusion phenotype. Taken together, our polykaryon formation and dye transfer experiments show that full fusion efficiency decreases with an increasing length of insertion. When 10 residues are inserted, only lipid mixing occurs. Perhaps the increased distance between fusion peptide and transmembrane domains provided when 10 rather than 8 residues are inserted identifies a critical length requirement for the transition between hemifusion and pore formation. Increasing the effective distance between the membrane-associating domains, by either direct insertions, as we have done here, or disrupting interactions which hold the antiparallel “leash” polypeptide to the central coiled coil in the region of the N cap, may be critical for full fusion activity (4, 28).

Attempts to generate infectious viruses incorporating these HAs were successful for most of the mutants that were shown to be functional for fusion (C-ins 4, 6, and 8; C-del 2 and 4; and N-ins 2). However, all of these viruses other than the N-ins 2 mutant were severely inhibited for replication, displaying titers that were several orders of magnitude lower than those of the WT on MDCK cells. Except for the C-ins 6 mutant, the titers at early passages were very similar to those reported for passage 6 in Table 3 and were genetically maintained following six passages at a low multiplicity. For the C-ins 6 mutant, plaques were not detected at early stages and were passaged undiluted until passage 4. At passage 4 through 6, plaques were detected, and titers on the order of 103 were observed. The entire HA gene of passage 6 viruses showed that several of these, including the WT, had mutations that caused an elevated fusion pH, which is a phenomenon that frequently occurs upon laboratory passage of prototype influenza virus strains and viruses generated from them (22). The HA1 mutation L226P and HA2 mutations R216K, F3L, I45T, and I6M either have been characterized previously as high-pH mutants or are located in positions that make this phenotype likely. Mutations of the arginine at HA2 position 124 were observed independently in two mutant passage series, the C-del 4 (R124K) and the C-ins 6 (R124G) viruses. The delta nitrogen of the arginine side chain forms an ionic interaction with E132 of a neighboring HA2 subunit. Therefore, mutation to either a lysine or a glycine would remove this stabilizing interaction and potentially lead to an elevated fusion pH. We do not know why such high-pH mutants are selected, since they do not result in increased virus yields. Perhaps, during low-multiplicity passages, the high-pH phenotype gives them a “head start” during entry and slightly increases their replication kinetics, but we have no evidence to support this.

The only change observed in the linker domains where the mutations were introduced also involved the C-ins 6 virus. In this virus, a large deletion in which the sequence ELKSGYKDW was converted to a single glycine residue was detected. This effectively changed a C-ins 6 mutant into a C-del 2 mutant. This was intriguing, as the sequence deleted did not encompass the six residues that were initially inserted but did encompass the WT sequence immediately adjacent to it (the insert was a SGYADW near-duplication of the WT sequence in which an A residue was utilized as opposed to a K at the fourth position). A comparison of this region in the HAs of viruses of different subtypes shows little direct sequence homology (27). The arginine at HA2 position 170 is completely conserved, and the next such residue in the C-terminal direction is L187, which resides near the putative start of the transmembrane domain. Among the HAs of different subtypes, the length of the peptide chain between these conserved residues varies by only one amino acid. This suggests that despite the lack of sequence homology, the length of the peptide chain encompassing the C-end segment addressed here has been relatively conserved. However, sequence variability at the start of the transmembrane domain makes it difficult to unambiguously define the length of the linker sequences.

These results and observations suggest that while there may be a degree of latitude regarding the length of the linking polypeptides for fusion activity, there are likely to be additional constraints on the lengths of these domains with regard to virus fitness. This is clearly apparent for the N-end mutants that are more critical for the folding of HA in the native conformation. With regard to membrane fusion activity, the observation that insertions and deletions of as many as eight residues at the C-end can remain functional is consistent with the hypothesis that this domain exists as a flexible polypeptide chain following acid-induced conformational changes. Deletion of the polypeptide chain by more than eight residues may affect HA cooperativity during the fusion process, which is thought to involve a minimum of three trimers (14), or the angle at which HAs align themselves with membranes during the fusion process, which varies according to the model for fusion which is invoked but is at present unknown. Similar explanations can be proposed for length limitations for the insertion mutations, or it may imply that the membranes are not drawn close enough to one another for fusion to proceed. It appears likely that constraints to virus fitness in addition to fusion capacity may be operating on the C-end linker sequences. A selection of these viruses (N-ins 4, C-del 6, and C-del 8) displayed fusion activity yet were not rescued as infectious viruses, and the collection of C-end mutant influenza viruses that were generated were all extremely debilitated for replication despite the fact that the respective HAs mediate fusion efficiently. We have shown previously with fusion peptide mutants that it is possible to rescue viruses that have very poor membrane fusion activity, including those for which the capacity to mediate polykaryons cannot be detected (13).

It is possible that C-end-length mutations could alter functional interactions with viral NA in a fashion similar to those of NA stalk deletion mutants such that the functional balance between HA and NA activity is affected (36). These mutant viruses are composed of the Aichi virus HA with a WSN virus background for the other seven gene segments, but we have made numerous other mutant HAs with the same gene constellation that replicated as well as the WT (22, 23). In addition, exogenously added NA had no effect on the replication of the mutant viruses generated here (data not shown). Alternatively, these mutations could also be somehow affecting how the cytoplasmic tail of HA associates with the other influenza virus proteins during virus packaging. At present, we cannot discriminate between these and other possible explanations for the inhibited replication of these mutants. However, they are comparable in some respects to results obtained with mutants in the stem region of the E1 glycoprotein of Semliki Forest virus, a class II VFP (21). This conserved region of alphavirus E1 proteins links the transmembrane domain to the core trimer, and deletions of up to 9 residues, but not 20, were shown to be fusogenic. Despite this, the mutant viruses that were fusion competent were dramatically inhibited in virus growth, as we observed for the influenza virus mutants reported here. For most of the E1 mutants, the inhibition was attributed to defects in particle assembly, and it will be interesting to investigate our mutants in more detail with respect to assembly and virus morphology.

The characteristics of the peptide sequences that link the structurally defined regions of class I fusion protein helical rods to membrane-associating domains are variable. For influenza virus HA, the structure of the entire ectodomain of HA2 lacking the N-terminal 22 amino acids that compose the fusion peptide has been determined (9). The trimeric structure of the peptide composed of HA2 residues 23 to 185 shows that at the N-terminal end, the α-helix of the core trimer is terminated at residue 38 by an N-cap structure formed by residues 34 to 37. This suggests that the residues between the N cap and the fusion peptide may form an extended, possibly flexible, polypeptide chain. The structure at the C-terminal end of the EBHA2 sequence shows that the polypeptide chain packs along a groove in the central coiled coil as an extended chain from residue 152 through to residue 178 at the end of the rod. It suggests that the polypeptide segment that links residue 178 to the transmembrane domain, which is thought to begin with residues W185-I186-conserved L187, also exists as an extended chain that may be flexible. For both Ebola virus GP2 (37) and the gp41 proteins of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 and simian immunodeficiency virus (6, 7, 38), approximately 18 residues of disordered structure link the C terminus of the rods to the transmembrane domain. At the N-terminal end, 12 residues of unknown structure link the start of the helix of the Ebola virus GP2 rod to the fusion peptide, whereas for simian immunodeficiency virus, this nonstructured linking sequence is 6 to 14 residues in length, depending on the designation of amino acids thought to compose the fusion peptide (6). Therefore, it has been postulated that for these proteins, as well as HA, the helical rod structures are linked to membranes by flexible extended-chain peptide segments.

Paramyxovirus F proteins have also been well characterized structurally, and their peptide linker regions have been analyzed experimentally. For these proteins, the α-helices that form the central coiled coil of the helical rod structure (heptad repeat region A) have been shown to extend directly into the fusion peptide sequence, which suggests that the fusion peptide inserts into the membrane as a rigid helical structure (1). It indicates that for these proteins, there is no requirement for a flexible linking domain between the six-helix bundle and the membrane at the N-terminal end. In addition, there appears to be no requirement for such a flexible peptide linking the C-terminal end to the transmembrane domain. For the F proteins of paramyxoviruses, the amino acid linker between heptad repeat region B and the transmembrane domain in the C-terminal portion of the protein can range from 5 to 12 amino acids, and the lengths and compositions of these linking regions have been examined for the F proteins of simian virus 5 (SV5) and human parainfluenzavirus type 2 (34, 45). For both of these F proteins, insertion mutations were deleterious for fusion activity. For SV5, F deletions of as many as eight residues were tolerated for full fusion activity, and for human parainfluenzavirus type 2, certain four-residue mutants were fusogenic, an eight-residue mutant displayed reduced fusion activity, and a 12-amino-acid mutant was functionally negative. Our observation that HAs containing small insertions as well as deletions in this region remain fusogenic may relate to the greater flexibility that is thought to be present in the N-end region of HA as opposed to paramyxovirus F proteins. Perhaps distinctions in lengths and structures of the peptides that link class I VFP helical rod structures to membrane-associating domains relate to differences with respect to fusion triggers, cofactors, or the environment in which the process takes place.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dick Compans for comments on the manuscript.

This work was supported by NIH Public Health Service grants AI66870 and AI/EB53359 to D.A.S. and contract HHSN266200700006C from the NIAID, NIH, as well as the Scottish Funding Council (R.J.R.).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 16 April 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Baker, K. A., R. E. Dutch, R. A. Lamb, and T. S. Jardetzky. 1999. Structural basis for paramyxovirus-mediated membrane fusion. Mol. Cell 3309-319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bizebard, T., B. Gigant, P. Rigolet, B. Rasmussen, O. Diat, P. Bosecke, S. A. Wharton, J. J. Skehel, and M. Knossow. 1995. Structure of influenza virus haemagglutinin complexed with a neutralizing antibody. Nature 37692-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blasco, R., and B. Moss. 1995. Selection of recombinant vaccinia viruses on the basis of plaque formation. Gene 158157-162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Borrego-Diaz, E., M. E. Peeples, R. M. Markosyan, G. B. Melikyan, and F. S. Cohen. 2003. Completion of trimeric hairpin formation of influenza virus hemagglutinin promotes fusion pore opening and enlargement. Virology 316234-244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bullough, P. A., F. M. Hughson, J. J. Skehel, and D. C. Wiley. 1994. Structure of influenza haemagglutinin at the pH of membrane fusion. Nature 37137-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Caffrey, M., M. Cai, J. Kaufman, S. J. Stahl, P. T. Wingfield, D. G. Covell, A. M. Gronenborn, and G. M. Clore. 1998. Three-dimensional solution structure of the 44 kDa ectodomain of SIV gp41. EMBO J. 174572-4584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chan, D. C., D. Fass, J. M. Berger, and P. S. Kim. 1997. Core structure of gp41 from the HIV envelope glycoprotein. Cell 89263-273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen, J., K. H. Lee, D. A. Steinhauer, D. J. Stevens, J. J. Skehel, and D. C. Wiley. 1998. Structure of the hemagglutinin precursor cleavage site, a determinant of influenza pathogenicity and the origin of the labile conformation. Cell 95409-417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen, J., J. J. Skehel, and D. C. Wiley. 1999. N- and C-terminal residues combine in the fusion-pH influenza hemagglutinin HA(2) subunit to form an N cap that terminates the triple-stranded coiled coil. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 968967-8972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen, J., J. J. Skehel, and D. C. Wiley. 1998. A polar octapeptide fused to the N-terminal fusion peptide solubilizes the influenza virus HA2 subunit ectodomain. Biochemistry 3713643-13649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen, J., S. A. Wharton, W. Weissenhorn, L. J. Calder, F. M. Hughson, J. J. Skehel, and D. C. Wiley. 1995. A soluble domain of the membrane-anchoring chain of influenza virus hemagglutinin (HA2) folds in Escherichia coli into the low-pH-induced conformation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 9212205-12209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Colman, P. M., and M. C. Lawrence. 2003. The structural biology of type I viral membrane fusion. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 4309-319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cross, K. J., S. A. Wharton, J. J. Skehel, D. C. Wiley, and D. A. Steinhauer. 2001. Studies on influenza haemagglutinin fusion peptide mutants generated by reverse genetics. EMBO J. 204432-4442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Danieli, T., S. L. Pelletier, Y. I. Henis, and J. M. White. 1996. Membrane fusion mediated by the influenza virus hemagglutinin requires the concerted action of at least three hemagglutinin trimers. J. Cell Biol. 133559-569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Daniels, R. S., A. R. Douglas, J. J. Skehel, and D. C. Wiley. 1983. Analyses of the antigenicity of influenza haemagglutinin at the pH optimum for virus-mediated membrane fusion. J. Gen. Virol. 641657-1662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fleury, D., B. Barrere, T. Bizebard, R. S. Daniels, J. J. Skehel, and M. Knossow. 1999. A complex of influenza hemagglutinin with a neutralizing antibody that binds outside the virus receptor binding site. Nat. Struct. Biol. 6530-534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jiang, S., K. Lin, N. Strick, and A. R. Neurath. 1993. HIV-1 inhibition by a peptide. Nature 365113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kielian, M., and F. A. Rey. 2006. Virus membrane-fusion proteins: more than one way to make a hairpin. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 467-76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lambert, D. M., S. Barney, A. L. Lambert, K. Guthrie, R. Medinas, D. E. Davis, T. Bucy, J. Erickson, G. Merutka, and S. R. Petteway, Jr. 1996. Peptides from conserved regions of paramyxovirus fusion (F) proteins are potent inhibitors of viral fusion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 932186-2191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li, M., Z. N. Li, Q. Yao, C. Yang, D. A. Steinhauer, and R. W. Compans. 2006. Murine leukemia virus R peptide inhibits influenza virus hemagglutinin-induced membrane fusion. J. Virol. 806106-6114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liao, M., and M. Kielian. 2006. Functions of the stem region of the Semliki Forest virus fusion protein during virus fusion and assembly. J. Virol. 8011362-11369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lin, Y. P., S. A. Wharton, J. Martin, J. J. Skehel, D. C. Wiley, and D. A. Steinhauer. 1997. Adaptation of egg-grown and transfectant influenza viruses for growth in mammalian cells: selection of hemagglutinin mutants with elevated pH of membrane fusion. Virology 233402-410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Martin, J., S. A. Wharton, Y. P. Lin, D. K. Takemoto, J. J. Skehel, D. C. Wiley, and D. A. Steinhauer. 1998. Studies of the binding properties of influenza hemagglutinin receptor-site mutants. Virology 241101-111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Melikyan, G. B., S. Lin, M. G. Roth, and F. S. Cohen. 1999. Amino acid sequence requirements of the transmembrane and cytoplasmic domains of influenza virus hemagglutinin for viable membrane fusion. Mol. Biol. Cell 101821-1836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Melikyan, G. B., R. M. Markosyan, H. Hemmati, M. K. Delmedico, D. M. Lambert, and F. S. Cohen. 2000. Evidence that the transition of HIV-1 gp41 into a six-helix bundle, not the bundle configuration, induces membrane fusion. J. Cell Biol. 151413-423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Neumann, G., T. Watanabe, H. Ito, S. Watanabe, H. Goto, P. Gao, M. Hughes, D. R. Perez, R. Donis, E. Hoffmann, G. Hobom, and Y. Kawaoka. 1999. Generation of influenza A viruses entirely from cloned cDNAs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 969345-9350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nobusawa, E., T. Aoyama, H. Kato, Y. Suzuki, Y. Tateno, and K. Nakajima. 1991. Comparison of complete amino acid sequences and receptor-binding properties among 13 serotypes of hemagglutinins of influenza A viruses. Virology 182475-485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Park, H. E., J. A. Gruenke, and J. M. White. 2003. Leash in the groove mechanism of membrane fusion. Nat. Struct. Biol. 101048-1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rapaport, D., M. Ovadia, and Y. Shai. 1995. A synthetic peptide corresponding to a conserved heptad repeat domain is a potent inhibitor of Sendai virus-cell fusion: an emerging similarity with functional domains of other viruses. EMBO J. 145524-5531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ruigrok, R. W., A. Aitken, L. J. Calder, S. R. Martin, J. J. Skehel, S. A. Wharton, W. Weis, and D. C. Wiley. 1988. Studies on the structure of the influenza virus haemagglutinin at the pH of membrane fusion. J. Gen. Virol. 692785-2795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Skehel, J. J., and D. C. Wiley. 1998. Coiled coils in both intracellular vesicle and viral membrane fusion. Cell 95871-874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Steinhauer, D. A., S. A. Wharton, J. J. Skehel, D. C. Wiley, and A. J. Hay. 1991. Amantadine selection of a mutant influenza virus containing an acid-stable hemagglutinin glycoprotein: evidence for virus-specific regulation of the pH of glycoprotein transport vesicles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 8811525-111529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Swalley, S. E., B. M. Baker, L. J. Calder, S. C. Harrison, J. J. Skehel, and D. C. Wiley. 2004. Full-length influenza hemagglutinin HA2 refolds into the trimeric low-pH-induced conformation. Biochemistry 435902-5911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tong, S., F. Yi, A. Martin, Q. Yao, M. Li, and R. W. Compans. 2001. Three membrane-proximal amino acids in the human parainfluenza type 2 (HPIV 2) F protein are critical for fusogenic activity. Virology 28052-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ujike, M., K. Nakajima, and E. Nobusawa. 2004. Influence of acylation sites of influenza B virus hemagglutinin on fusion pore formation and dilation. J. Virol. 7811536-11543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wagner, R., M. Matrosovich, and H. D. Klenk. 2002. Functional balance between haemagglutinin and neuraminidase in influenza virus infections. Rev. Med. Virol. 12159-166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Weissenhorn, W., A. Carfi, K. H. Lee, J. J. Skehel, and D. C. Wiley. 1998. Crystal structure of the Ebola virus membrane fusion subunit, GP2, from the envelope glycoprotein ectodomain. Mol. Cell 2605-616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Weissenhorn, W., A. Dessen, S. C. Harrison, J. J. Skehel, and D. C. Wiley. 1997. Atomic structure of the ectodomain from HIV-1 gp41. Nature 387426-430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Weissenhorn, W., A. Hinz, and Y. Gaudin. 2007. Virus membrane fusion. FEBS Lett. 5812150-2155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wild, C. T., D. C. Shugars, T. K. Greenwell, C. B. McDanal, and T. J. Matthews. 1994. Peptides corresponding to a predictive alpha-helical domain of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp41 are potent inhibitors of virus infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 919770-9774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wilson, I. A., J. J. Skehel, and D. C. Wiley. 1981. Structure of the haemagglutinin membrane glycoprotein of influenza virus at 3 Å resolution. Nature 289366-373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wrigley, N. G., E. B. Brown, R. S. Daniels, A. R. Douglas, J. J. Skehel, and D. C. Wiley. 1983. Electron microscopy of influenza haemagglutinin-monoclonal antibody complexes. Virology 131308-314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yao, Q., and R. W. Compans. 1996. Peptides corresponding to the heptad repeat sequence of human parainfluenza virus fusion protein are potent inhibitors of virus infection. Virology 223103-112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhao, X., M. Singh, V. N. Malashkevich, and P. S. Kim. 2000. Structural characterization of the human respiratory syncytial virus fusion protein core. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 9714172-14177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhou, J., R. E. Dutch, and R. A. Lamb. 1997. Proper spacing between heptad repeat B and the transmembrane domain boundary of the paramyxovirus SV5 F protein is critical for biological activity. Virology 239327-339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]