Abstract

Unisexual all-female lizards of the genus Darevskia that are well adapted to various habitats are known to reproduce normally by true parthenogenesis. Although they consist of unisexual lineages and lack effective genetic recombination, they are characterized by some level of genetic polymorphism. To reveal the mutational contribution to overall genetic variability, the most straightforward and conclusive way is the direct detection of mutation events in pedigree genotyping. Earlier we selected from genomic library of D. unisexualis two polymorphic microsatellite containg loci Du281 and Du215. In this study, these two loci were analyzed to detect possible de novo mutations in 168 parthenogenetic offspring of 49 D. unisexualis mothers and in 147 offspring of 50 D. armeniaca mothers . No mutant alleles were detected in D. armeniaca offspring at both loci, and in D. unisexualis offspring at the Du215 locus. There were a total of seven mutational events in the germ lines of four of the 49 D. unisexualis mothers at the Du281 locus, yielding the mutation rate of 0.1428 events per germ line tissue. Sequencing of the mutant alleles has shown that most mutations occur via deletion or insertion of single microsatellite repeat being identical in all offspring of the family. This indicates that such mutations emerge at the early stages of embryogenesis. In this study we characterized single highly unstable (GATA)n containing locus in parthenogenetic lizard species D. unisexualis. Besides, we characterized various types of mutant alleles of this locus found in the D. unisexualis offspring of the first generation. Our data has shown that microsatellite mutations at highly unstable loci can make a significant contribution to population variability of parthenogenetic lizards.

Introduction

Unisexuality in vertebrates has attracted wide attention since it was discovered. In squamate reptiles, unisexuality originates from interspecific hybridization between bisexual species and represents true parthenogenesis [1], [2]. They propagate via an aberrant gametogenetic mechanism that inhibits genetic recombination and causes clonal inheritance [1]. Hence the progeny consist of only genetically identical females with clonal inheritance in the next generation. Clonal reproduction and clonal diversity are the two features of unisexual vertebrates that make them attractive as model organisms in such areas as evolutionary ecology, genetics, cellular and molecular biology.

Parthenogenetic lizards of the genus Darevskia (formerly Lacerta [3]) were the first reptiles to be identified as unisexual [4]. Seven diploid all-female species are currently known, all from the Caucasus Mountains of Armenia [1], [5], [6]. Previous studies on these parthenogenetic species revealed some degree of allozyme variation [7]–[11] and low variability of mitochondrial DNA [12]. However multilocus DNA fingerprinting revealed very high levels of genetic variation in parthenogenetic populations of Darevskia unisexualis, D. armeniaca, D. dahli and D. rostombecovi [13]–[16]. The possible sources of such variation in parthenogenetic populations may be associated with multiple origins of clones from different pairs of founders, mutations, rare hybridization events, or some level of genetic recombination [8], [17]–[20]. However, the contribution of each of those events to the overall genetic variation remains unknown. The most straightforward and conclusive way to assess the mutational contribution to genetic variation is the direct detection of mutational events from pedigree genotyping [21]. Multilocus DNA fingerprinting with various microsatellite probes detected intrafamily variability of fingerprint patterns in D. unisexualis and D. armeniaca lizards [22], 23. These results imply that unstable loci may exist intheir genomes, but the real nature of such loci and supposed mutations remains obscure.

Recently Korchagin et al. (2007) cloned and sequenced a number of microsatellite loci of the parthenogenetic species D. unisexualis. Among several loci analyzed in detail only two, Du281 (GenBank accession number AY 442143) and Du215 (GenBank accession number AY 574928), which contain (GATA)n repeats were polymorphic. However until now there was no information about genetical stability of those loci.

In the present work, Du281 and Du215 were tested in a pedigree based analysis to enable the detection of possible de novo mutations in parthenogenetic offspring of D. unisexualis and D. armeniaca lizards.

Materials and Methods

Reproductively mature females of D. unisexualis and D. armeniaca were collected from natural habitats of western and central Armenia. The animals were maintained in separate enclosures in the laboratory until they began to produce eggs. The eggs were incubated under laboratory conditions. Genomic DNA was extracted from blood by standard phenol-chloroform extraction and resuspended in TE_buffer of pH 8.0. The loci Du281 and Du215 were amplified with the previously described primers (Du281: 5′TTGCTAATCTGAATAACTG3′, 5′TCCTGCTGAGAAAGACCA3′; Du215: 5′CAACTAGCAGTAGCTCTCCAGA3′, 5′CCAGACAGGCCCCAACTT3′) [24]. PCR reaction mix (20 µl) contained 20–40 ng genomic DNA, 1× PCR buffer (Dialat), 2 mM MgCl2, dNTP 0.25 mM each, and 0.625 units of Taq-polymerase (Dialat). Amplification conditions were: 94C for 3 min and then 40 cycles of 94C 1 min, 50C for 40 s, 72C for 40 s, followed by 72C for 5 min. The products, averaging about 200 bp in size, were separated by electrophoresis on a 8% native polyacrylamide gel (PAAG) and visualized on a ultraviolet light table following ethidium bromide staining. Amplified fragments were excised from the PAAG, purified and cloned into pMos blue vectors following standard procedures (pMos blueBlunt ended Cloning kit RPN 5110, Amersham Biosciences). The clones were amplified in MOSBlue competent cells grown at 37°C, and sequenced. The PCR products were cloned and sequenced using the chain termination reaction with ABI PRISM® BigDye™ Terminator v. 3.1 on an ABI PRISM 3100-Avant Genetic Analyzer.

The sequences of the allelic variants of the PCR products were compared using the MegAlign program (DNASTAR).

All animal procedures were carried out according to ethical principles and scientific standards of the ethical committee of Moscow State University.

Results

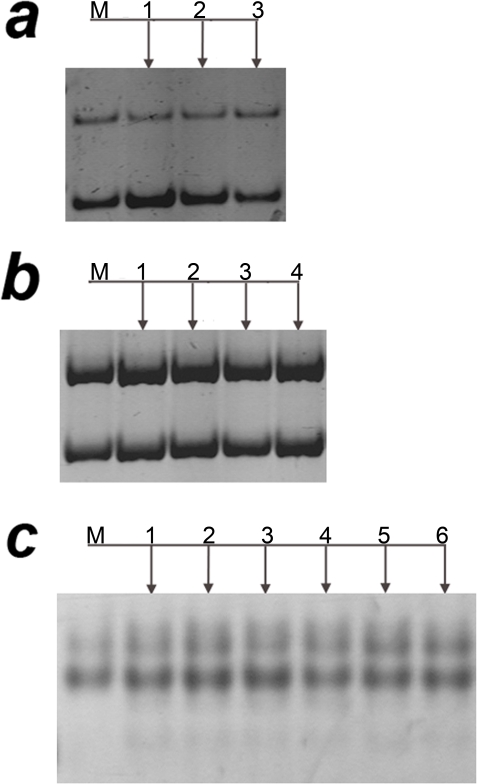

In total DNA samples of 217 lizards (49 mothers and 168 offspring ) of D. unisexualis and 197 lizards (50 mothers and 147 offspring) of D. armeniaca were screened by locus-specific PCR. Mutant alleles were detected as changes in the electrophoretic mobility of PCR amplification products obtained from mother and their offspring. No mutant alleles were detected in D. armeniaca offspring at both Du281 and Du215 loci, and in D. unisexualis offspring at Du215 locus. Figure 1 shows typical example of families where no intrafamily variation of PCR products was revealed. At the same time, 15 mutant alleles among offspring of four D. unisexualis mothers were found at the Du281 locus (Fig. 2). These data show that the Du281 locus of D. unisexualis is highly mutable, with an estimated mutation rate of 0.1428 events per germ line tissue.

Figure 1. Examples of families where where no intrafamily variation of PCR products was revealed.

a – Du281 locus, D. armeniaca family; b – 215 locus, D. armeniaca family; c – 215 locus, D. unisexualis family. Maternal DNAs are marked by M, offspring DNAs are shown by arrows and numbered in each family.

Figure 2. Intrafamily electrophoretic variability of PCR products amplified at Du281 locus of parthenogenetic lizards Darevskia unisexualis.

a – family 1, b – family 2, c – family 3, d – family 4. Maternal DNAs are marked by M1–M4 respectively; offspring DNAs are shown by arrows and numbered in each family.

To analyze the molecular structure of mutant alleles, we cloned and sequenced PCR products of the Du 281 locus from maternal and mutant offspring of D. unisexualis. Comparison of nucleotide sequences of mothers and their offspring revealed mutations only in (GATA)n microsatellite clusters, while no mutations were found in the flanking regions (Table 1). The haplotypes (T-A-T and C-G-C), formed by fixed point mutations in the flanking regions of microsatellite cluster, and specific for allelic variants of Du281 [24] were used to mark maternal and corresponding offspring alleles. In family 1, consisting of the mother and one offspring, the deletion of one GATA monomer in microsatellite cluster was found in both offspring alleles. In family 2, consisting of the mother and five offspring, only one offspring allele marked by haplotype C-G-C was mutant with the deletion of GATATA in the microsatellite cluster of all offspring. In family 3, consisting of the mother and two offspring, an insertion of one GATA monomer was found in the microsatellite cluster of both offspring alleles. Family 4, consisting of the mother and four offspring, represent a more complicated case. While no mutations were observed among offspring alleles marked by haplotype T-A-T, different pattern of mutation was found among offspring alleles marked by haplotype C-G-C. In three offspring the mutatnt alleles revealed a deletion of one GATA monomer, but in another offspring a GATATA sequence was lost in the microsatellite cluster.

Table 1. Allelic variants of microsatellite clusters of Du281 locus in parthenogenetic lizard families D. unisexualis.

| Family 1. | |

| Maternal (M1) allele 1 | •••T•••A•••(GATA)9 (GATA) GAT(GATA)TA(GATA)•••T••• |

| Offspring (1) allele 1 | •••T•••A•••(GATA)9 - - - - GAT(GATA)TA(GATA)•••T••• |

| Maternal (M1) allele 2 | •••C•••G•••(GATA)9 (GATA) (GATA)TA(GATA)•••G••• |

| Offspring (1) allele 2 | •••C•••G•••(GATA)9 - - - - (GATA)TA(GATA)•••G••• |

| Family 2. | |

| Maternal (M2) allele 1 | •••T•••A•••(GATA)9 GAT(GATA)TA(GATA)•••T••• |

| Offspring (1–5) allele 1 | •••T•••A•••(GATA)9 GAT(GATA)TA(GATA)•••T••• |

| Maternal (M2) allele 2 | •••C•••G•••(GATA)9 (GATA)TA(GATA)•••G••• |

| Offspring (1–5) allele 2 | •••C•••G•••(GATA)9 - - - - - - (GATA)•••G••• |

| Family 3. | |

| Maternal (M3) allele 1 | •••T•••A•••(GATA)9 - - - - GAT(GATA)TA(GATA)•••T••• |

| Offspring (1, 2) allele 1 | •••T•••A•••(GATA)9 (GATA)GAT(GATA)TA(GATA)•••T••• |

| Maternal (M3) allele 2 | •••C•••G•••(GATA)9 - - - - (GATA)TA(GATA)•••G••• |

| Offspring (1, 2) allele 2 | •••C•••G•••(GATA)9 (GATA) (GATA)TA(GATA)•••G••• |

| Family 4. | |

| Maternal (M4) allele 1 | •••T•••A•••(GATA)9 GAT(GATA)TA(GATA)•••T••• |

| Offspring (1, 3, 4) allele 1 | •••T•••A•••(GATA)9 GAT(GATA)TA(GATA)•••T••• |

| Offspring (2) allele 1 | •••T•••A•••(GATA)9 GAT(GATA)TA(GATA)•••T••• |

| Maternal (M4) allele 2 | •••C•••G•••(GATA)9 (GATA) (GATA)TA(GATA)•••G••• |

| Offspring (1, 3, 4) allele 2 | •••C•••G•••(GATA)9 - - - - (GATA)TA (GATA)•••G••• |

| Offspring (2) allele2 | •••C•••G•••(GATA)9 (GATA) - - - - - - (GATA)•••G••• |

Variations in microsatellite clusters are denoted by bold letters. T-A-T and C-G-C are haplotypes specific for allelic variants of D. unisexualis [24]. In Family 2 the observed changes were the same in all offspring (1–5). In family 3 the observed changes were the same in all offspring(1, 2). In Family 4 the observed changes are the same in three offspring (1, 3 and 4).

In summary, single repeat unit changes dominated (in microsatellite clusters of all offspring of the 1st and 3rd family and offspring 1, 2 and 4 of the 4th family). In two families (all offspring of family 2 and offspring 2 of family 4) maternal and offspring microsatellite differed from each other by the deletion of GATATA imperfect monomer. Mutation may occur in both (1st and 3rd families) or only in one allele (2nd, 4th and 5th family). In three out of four families the patterns of mutations were similar in all offspring. The offspring of family 4 showed different pattern of mutations: in most individuals the mutant allele arose as a result of the loss of one microsatellite monomer, while in another it was the loss of imperfect monomer GATATA.

Discussion

Unisexual vertebrates are useful model organisms for studying genome diversity because various mutational events can be easily detected in in pedigree genotyping. The genetic variation of the majority of such species is low in comparison with their sexual progenitors, and they face severe genetic and ecological restraints [2], [25]. Their genome and clonal diversity may arise as a result of mutations, multiple hybridization events, or some level of recombination occurring during continued clonal reproduction and the evolution of species [26]. In this study we characterized single highly unstable (GATA)n containing locus in parthenogenetic lizard species D. unisexualis. Additionally, we characterized various types of mutant alleles of this locus found in the D. unisexualis offspring of the first generation. Comparison of maternal and offspring alleles of two polymorphic loci revealed de novo mutations only at the Du281 locus in D. unisexualis offspring with the mutation rate of 0.1428 events per germ line tissue. This correlates with a higher level of population polymorphism in Du281 in comparison with Du215. For instance, six and three allelic variants were detected among 65 D. unisexualis individuals for Du281 and Du215, respectively [24]. According to Malysheva [22] only three allelic variants of the Du215 locus were detected in D. armeniaca populations. The obtained mutation rate for Du281 is comparable with the earlier results of DNA fingerprinting analysis. For instance, in D. unisexualis families the observed mutational rate was 0.9×10−2 per microsatellite band/per sibling when using a (GATA)4 hybridization probe [23]. These values are also within the range reported for individual microsatellite loci in bisexual species (from 10−2 to 10−4 per locus/per gamete) [21], [27]–[29]. For instance, pedigree analysis of mutations at human microsatellite loci gave estimates of mean mutational rates of 3×10−3–6×10−4 [21]. Genethon's extensive genotyping of >500 microsatellite loci in human population has suggested a lower mean genomic mutation rate, of 10−4 [30], [31]. A mutation rate of 5.7×10−3 was reported for (AAAG)n tetranucleotide repeat locus in the barn swallow (Hirunda rustica) [27]. In the Australian lizard Egernia stokesii the mutational rate for (AAAG)n locus was 4.2×10−2 [28]. A hypervariable microsatellite (TATC)n with a mutation rate of 1.7×10−2 was found in the human X chromosome [32]. Some rodent-specific loci containing (GGCAGG)n repeat motif showed germ-line mutation rates up to 8.8×10−2 per gamete [33].

Direct records of new length variants identified in comparisons between parents and offspring loci may be considered the most unambiguous way for analyzing mutational process in the germ line [27], [29]. Unisexual reptiles reproduce clonally and have a low level of recombinational events, thus all of the observed changes in microsatellite cluster are probably mutations. In three out of four D. unisexualis families the patterns of mutations were similar in all offspring, suggesting that mutation must be occurring in the mitotic creation of germ-line tissue, such that multiple oocytes would carry the same mutation.. The offspring of one family (offspring 3, family 4) showed different pattern of mutations: in most offsprings the mutant allele arose following the loss of a monomer, while in one offspring the imperfect monomer GATATA was lost. This offspring could mutate twice, first together with all other offspring and the second time at a later stage of differentiation, in turns, this mutation could have occurred once at the later stage of differentiation of germ line cells or even in a zygote. Studies of germ line microsatellite mutations, mainly in humans, found that mutations involving the gain or loss of a single repeat unit are much more frequent than multistep mutations [29]. In our findings we observed a mutation that occurred following the loss of an imperfect (GATATA) monomer, i.e. it involved more than one monomer. In other three families the changes of electrophoretic mobility were caused by the deletion/insertion of one GATA monomer, which fits with the stepwise mutation model [34].

Data from individual loci in several bisexual species [35] and pooled data on dinucleotide repeats in human genome [36], [37] show directionality in the mutation process, with an excess of insertions over deletions. On the contrary, our data showed a significant trend for mutation to lead to a decrease in allele size recorded in 11 out of 15 observed cases. This may be due to the peculiarities of structural organization of Du281 locus, or to the specific features of the hybrid genome of D. unisexualis. Our data has shown that microsatellite mutations at highly unstable loci can make a significant contribution to population variability of parthenogenetic lizards.

Acknowledgments

We are especially thankful to Olga N. Tokarskaya for helpful discussions, suggestions and comments.

Footnotes

Competing Interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Funding: This work was partly supported by the Leading Scientific School and Program of President of Russian Federation for financial support of young scientist 02.120.11.23498 MK-4748.2007.4. and MK-2106.2008.4. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Darevsky IS, Kupriyanova LA, Uzzel T. Parthenogenesis in Reptiles. In: Gans C, Billett DF, editors. Biology of Reptilia. Vol. 15. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1985. pp. 413–526. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dawley RM. An introduction to unisexual vertebrates. In: Dawley RM, Bogart JP, editors. Evolution and Ecology of Unisexual vertebrates. Vol. 466. Albany., N.Y.: New York State Museum Bull; 1989. pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arribas OJ. Phylogeny and relationships of the mountain lizards of Europe and Near East (Archaeolacerta Merttens, 1921, Sensu Lato) and their relationships among the Eurasian Lacertid lizards. Russian Journal of Herpetology. 1999;6(1):1–22. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Darevsky IS. Natural parthenogenesis in certain subspecies of rock lizards (Lacerta saxicola Eversmann). Doklady Academii Nauk SSSR Biological Sciences. 1958;122:730–732. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Darevsky IS. Natural parthenogenesis in a polymorphic group of Caucasian rock lizards related to Lacerta saxicola Eversmann. Journal of Herpetology. 1966;2:65–69. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Uzzell T, Darevsky IS. Biochemical evidence for the hybrid origin of the parthenogenetic species of the Lacerta saxicola complex (Sauria: Lacertidae), with a discussion of some ecological and evolutionary implications. Copeia. 1975;2:204–222. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fu J, MacCulloch RD, Murphy RW. The parthenogenetic Rock Lizard Lacerta unisexualis: An Example of Limited Genetic Polymorphism. Journal of Molecular Evolution. 1998;46:127–130. doi: 10.1007/pl00013146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fu J, MacCulloch RD, Murphy RW, Darevsky IS. Divergence of the cytohrome b gene in the Lacerta raddei complex and its parthenogenetic daughter species: Evidence for recent multiple origins. Copeia. 2000;2:432–440. [Google Scholar]

- 9.MacCulloch RD, Murphy RW, Kupriyanova LA. Clonal variation in the parthenogenetic rock lizard Lacerta armeniaca. Genome. 1995;38:1057–1060. doi: 10.1139/g95-141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.MacCulloch RD, Murphy RW, Kupriyanova LA, Darevsky IS. The Caucasian rock lizard Lacerta rostombekovi: a monoclonal parthenogenetic vertebrate. Biochemical Systematics and Ecology. 1997;25:33–37. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Murphy RW, Darevsky IS, MacCulloch RD. Old age, multiple formations or genetic plasticity? Clonal diversity in the uniparental Caucasian rock lizard Lacerta dahli. Genetica. 1997;101:125–130. doi: 10.1023/A:1018392603062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moritz C, Uzzel T, Spolsky C, Hotz H, Darevsky IS, et al. The maternal ancestry and approximate age of parthenogenetic species of Caucasian rock lizards (Lacerta: Lacertidae). Genetica. 1992;87:53–62. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kan NG, Petrosyan VG, Martirosyan IA, Ryskov AP, Darevsky IS, et al. Genomic polymorphism of mini- and microsatellite loci of the parthenogenetic Lacerta dahli revealed by DNA fingerprinting. Molecular Biology. 1998;32:672–678. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Martirosyan IA, Ryskov AP, Petrosyan VG, Arakelyan MS, Aslanyan AV, et al. Variation of mini- and microsatellite DNA markers in populations of parthenogenetic rock lizard Darevskia rostombekovi. Russian Journal of Genetics. 2002;38:691–698. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ryskov AP, Martirosyan IA, Badaeva TN, Korchagin VI, Danielyan FD, et al. Hyper unstable (TCT/TCC)n microsatellite loci in parthenogenetic lizards Darevskia unisexualis (Lacertidae). Russian Journal of Genetics. 2002;39:986–992. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tokarskaya ON, Kan NG, Petrosyan VG. Genetic variation in parthenogenetic Caucasian rock lizards of the genus Lacerta (L. dahli, L. armeniaca, L.unisexualis) analyzed by DNA fingerprinting. Molecular Genetics and Genomics. 2001;265:812–819. doi: 10.1007/s004380100475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cole CJ, Dessauer HC, Barrowclough GF. Hybrid origin of a unisexual species of whiptail lizard, Cnemidophorus neomexicanus, in western North America: new evidence and a review. American Museum novitates New York, N.Y.: American Museum of Natural History. 1988;2905:1–38. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moritz C, Donnelan S, Adams M, Baverstock PR. The origin and evolution of parthenogenesis in Heteronotia binoei (Gekkonidae): extensive genotypic diversity among parthenogens. Evolution. 1989;43:994–1003. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1989.tb02545.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Parker ED. Phenotypic consequences of parthenogenesis in Cnemidophorus lizards. Invariability in parthenogenetic and sexual populations. Evolution. 1979;33:1150–1166. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1979.tb04769.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Parker ED, Selander RK. The organization of genetic diversity in the parthenogenetic lizard Cnemidophorus tesselatus. Genetics. 1976;84:791–805. doi: 10.1093/genetics/84.4.791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ellegren H. Microsatellite mutations in germline: implications for evolutionary inference. Trends in Genetics. 2000;16:551–558. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(00)02139-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Malysheva DN, Vergun AA, Tokarskaya ON, Sevastianova GA, Danielyan FD, et al. Nucleotide sequences of allelic variants of microsatellite containing loci Du 215 (arm) in parthenogenetic species Darevskia armeniaca (Lacertidae). Russian journal of genetics. 2007;43:170–175. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tokarskaya ON, Martirosyan IA, Badaeva TN, Malysheva DN, Korchagin VI, et al. Instability of (GATA)n microsatellite loci in parthenogenetic Caucasian rock lizard Darevskia unisexualis (Lacertidae). Molecular Genetics and Genomics. 2004;270:509–513. doi: 10.1007/s00438-003-0936-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Korchagin VI, Badaeva TN, Tokarskaya ON, Martirosyan IA, Darevsky IS, et al. Molecular characterization of allelic variants of (GATA)n microsatellite loci in parthenogenetic lizards Darevskia unisexualis (Lacertidae). Gene. 2007;392:126–133. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2006.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grebelnyi SD. How many clonal species are there in the world. Invertebrate zoology. 2005;2:79–102. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Murphy RW, Fu J, MacCulloch RD, Darevsky IS, Kupriyanova LA. A fine line between sex and unisexuality: the phylogenetic constraints on parthenogenesis in lacertid lizards. Zoological Journal of Linnean Society. 2000;130:527–549. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brohede J, Primmer CR, Møller A, Ellegren H. Heterogeneity in the rate and pattern of germline mutation at individual microsatellite loci. Nucleic Acids Research. 2002;30:1997–2003. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.9.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gardner MG, Bull CM, Cooper SJB, Duffield GA. Microsatellite mutations in litters of the Australian lizard Egernia stokesii. Journal of Evolutionary Biology. 2000;13:551–560. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weber JL, Wong C. Mutation of human short tandem repeats. Human Molecular Genetics. 1993;2:1123–1128. doi: 10.1093/hmg/2.8.1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dib C, Faure S, Fizames C, Samson D, Drouot N. A comprehensive genetic map of the human genome on 5,264 microsatellites. Nature. 1966;380:152–154. doi: 10.1038/380152a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Weissbach J, Gyapay G, Dib C, Vignal A, Morissette J. A second-generation linkage map of the human genome. Nature. 1992;359:794–801. doi: 10.1038/359794a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mahtani MM, Willard HF. A polymorphic X-linked tetranucleotide repeat locus displaying a high rate of new mutation: implications for mechanisms of mutation at short tandem repeat loci. Human Molecular Genetics. 1993;2:431–437. doi: 10.1093/hmg/2.4.431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mitani K, Takahashi Y, Kominami R. A GGCAGG motif in minisatellites affecting their germline instability. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1990;265:15203–15210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kimura M, Ohta T. Stepwise mutation model and distribution of allelic frequencies in a finite population. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA. 1978;75:2868–2872. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.6.2868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Primmer C, Salino RN, Møller AP, Ellegren H. Directional evolution in germline microsatellite mutations. Nature Genetics. 1996;13:391–393. doi: 10.1038/ng0896-391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Amos W, Sawcer SJ, Feacer RW, Rubinsztein DC. Microsatellites show mutational bias and heterozygote instability. Nature Genetics. 1996;13:390–391. doi: 10.1038/ng0896-390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ellegren H. Heterogeneous mutation process in human microsatellite DNA sequences. Nature Genetics. 2000;24:400–402. doi: 10.1038/74249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]