Abstract

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is a significant healthcare concern worldwide that affects more than 165 million individuals leading to cardiovascular disease, nephropathy, retinopathy, and widespread disease of both the peripheral and central nervous systems. The incidence of undiagnosed diabetes, impaired glucose tolerance, and impaired fasting glucose levels raises future concerns in regards to the financial and patient care resources that will be necessary to care for patients with DM. Interestingly, disease of the nervous system can become one of the most debilitating complications and affect sensitive cognitive regions of the brain, such as the hippocampus that modulates memory function, resulting in significant functional impairment and dementia. Oxidative stress forms the foundation for the induction of multiple cellular pathways that can ultimately lead to both the onset and subsequent complications of DM. In particular, novel pathways that involve metabotropic receptor signaling, protein-tyrosine phosphatases, Wnt proteins, Akt, GSK-3β, and forkhead transcription factors may be responsible for the onset and progression of complications form DM. Further knowledge acquired in understanding the complexity of DM and its ability to impair cellular systems throughout the body will foster new strategies for the treatment of DM and its complications.

Keywords: Apoptosis, Akt, Alzheimer’s disease, diabetes, erythropoietin, Forkhead, FOXO, glycogen synthase kinase, metabotropic, mitochondria, Oxidative stress, protein-tyrosine phosphatases, uncoupling proteins, Wnt

CELLULAR INJURY AND OXIDATIVE STRESS

During cellular injury, oxygen free radicals can be produced in significant quantities during the reduction of oxygen and ultimately result in oxidative stress with cell death. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) consist of oxygen free radicals and other chemical entities that include superoxide free radicals, hydrogen peroxide, singlet oxygen, nitric oxide (NO), and peroxynitrite [1]. Most species are produced at low levels during normal physiological conditions and are scavenged by endogenous antioxidant systems that include superoxide dismutase (SOD), glutathione peroxidase, catalase, and small molecule substances such as vitamins C and E. Superoxide radical is the most commonly occurring oxygen free radical that can result from xanthine oxidase, NADPH oxidases and cytochrome P450. Superoxide produces hydrogen peroxide through the Haber-Weiss reaction in the presence of ferrous iron by manganese (Mn)-SOD or copper (Cu)-SOD. In the presence of transition elements, a reaction of hydrogen peroxide with superoxide results in the formation of hydroxyl radical, the most active oxygen free radical. Hydroxyl radical alternatively may be formed through an interaction between superoxide radical and NO [2]. NO interacts with superoxide radical to form peroxynitrite that can further lead to the generation of peroxynitrous acid. Hydroxyl radical is produced from the spontaneous decomposition of peroxynitrous acid. NO itself and peroxynitrite are also recognized as active oxygen free radicals. In addition to directly altering cellular function, NO may work through peroxynitrite that is potentially considered a more potent radical than NO itself [3].

Oxidative stress represents a significant mechanism for the destruction of cells that can involve apoptotic cell injury [4–5]. Apoptosis consists of membrane phosphatidylserine (PS) exposure and DNA fragmentation [6] and can contribute to a variety of disease states that especially involve the nervous system such as diabetes, ischemia, Alzheimer’s disease, and trauma [7–11]. As an early event in the dynamics of cellular apoptosis, membrane PS externalization can become a signal for the phagocytosis of cells [1, 12]. Cells expressing externalized PS may be removed by microglia [13–14]. In addition, membrane PS externalization on platelets has been associated with clot formation in the vascular cell system [15].

In contrast to the early externalization of membrane PS residues, the cleavage of genomic DNA into fragments is considered to be a delayed event that occurs late during apoptosis [16 19]. Several enzymes responsible for DNA degradation have been differentiated based on their ionic sensitivities to zinc [20] and magnesium [21]. Calcium, a critical independent component that can determine cell survival [22], also may determine endonuclease activity through calcium/magnesium - dependent endonucleases such as DNase I [23]. Other enzymes that may degrade DNA include the acidic, cation independent endonuclease (DNase II) [24], cyclophilins [25], and the 97 kDa magnesium - dependent endonuclease [26]. Three separate endonuclease activities are present in neurons that include a constitutive acidic cation-independent endonuclease, a constitutive calcium/magnesium-dependent endonuclease, and an inducible magnesium dependent endonuclease [27].

Oxidative stress can lead to apoptosis in a variety of cell types that involve neurons, endothelial cells (ECs), cardiomyocytes, and smooth muscle cells through multiple cellular pathways [28–29]. The production of ROS can lead to cell injury through a number of processes that involve the peroxidation of cellular membrane lipids [30], the peroxidation of docosahexaenoic acid, a precursor of neuroprotective docosanoids [31], and the oxidation of proteins that yield protein carbonyl derivatives and nitrotyrosine [32]. In addition to the detrimental effects to cellular integrity, ROS can inhibit complex enzymes in the electron transport chain of the mitochondria resulting in the blockade of mitochondrial respiration [33]. Oxidative stress, such as during NO exposure, results in nuclei condensation and DNA fragmentation [27, 34–36]. In neurons, NO exposure produces apoptotic death in hippocampal and dopaminergic neurons [37–40]. Injury during NO exposure also can become synergistic with hydrogen peroxide to render neurons more sensitive to oxidative injury [41–42]. Externalization of membrane PS residues also occurs in neurons during anoxia [43], NO exposure [44], or during the administration of agents that induce the production of reactive oxygen species, such as 6-hydroxydopamine [45].

OXIDATIVE STRESS, DIABETIC CELL INJURY, CLINICAL RELEVANCE, AND INSULIN RESISTANCE

Diabetes mellitus (DM) affects at least 16 million Americans, more than 165 million individuals worldwide [46], and by the year 2030 more than 360 million individuals will be afflicted with DM and its debilitating conditions [47]. Type 2 DM represents at least 80 percent of all diabetics and is dramatically increasing in incidence as a result of changes in human behavior and increased body mass index [48]. Type 1 insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus (IDDM) accounts for only 5–10 percent of all diabetics. Yet, it presents a significant health concern, since this disorder begins early in life and leads to long-term complications throughout the body involving cardiovascular, renal, and nervous system disease [49].

Interestingly, disease of the nervous system can become the most debilitating complications for DM and affect sensitive cognitive regions of the brain, such as the hippocampus that modulates memory function, resulting in significant functional impairment and dementia [50–51]. Furthermore, both focal and generalized neuropathies, especially in conjunction with vascular disease, can result in severe disability [52]. In a prospective population based study of 6,370 elderly individuals, patients with DM had an approximate double risk for the development of dementia [53]. DM also has been found to increase the risk for vascular dementia in elderly subjects [54–55]. Although some studies have found that diabetic patients may have significantly less neuritic plaques and neurofibrillary tangles than non-diabetic patients [56], other investigators report a modest adjusted relative risk of Alzheimer’s disease in patients with diabetes as compared with those without diabetes to be 1.3 [57]. Additional studies have described the reduced expression of genes encoding insulin in Alzheimer’s patients that suggests a potential link between DM and the development of Alzheimer’s disease [58]. In animal models with brain/neuronal insulin receptor knockouts, loss of insulin signaling appears to be linked to increased phosphorylation of the microtubule-associated protein tau that occurs during Alzheimer’s disease [59].

The incidence of undiagnosed diabetes and impaired glucose tolerance in the young raises further concerns. Individuals with impaired glucose tolerance have a greater than 2 times the risk for the development of diabetic complications than individuals with normal glucose tolerance [60]. Healthcare costs for diabetic complications are a significant driver for government resource consumption with costs of $214.8 million for outpatient expenditures and $1.45 billion for inpatient expenditures [61]. If one examines cognitive impairments resulting from diabetes in the general population that can mimic Alzheimer’s disease [4], annual costs equal $100 billion [62–64].

Type I DM is associated with the presence of alleles of the Human leukocyte antigen (HLA) class II genes within the major histocompatibility complex (MHC). The disorder is considered to have autoimmune origins resulting from inflammatory infiltration of the islets of Langerhans and the selective destruction of β-cells in the pancreas that leads to insulin loss [65]. Monogenic inheritance does not appear to lead to Type I DM since studies illustrate that multiple loci with possible epistatic interactions among other loci may be responsible for genetic transmission [66–67]. Yet, a variety of environmental factors also may play a significant role with Type I DM. For example, some studies have suggested that Type I DM in monozygotic twins can occur with a cumulative risk from birth to 35 years of age of seventy percent [68–69]. In addition, other work suggests a concordance between monozygotic twins to be approximately fifty percent [70], suggesting that environmental factors may lead to a predisposition for Type I DM.

In Type I DM, activation of T-cell clones that are capable of recognizing and destroying β-cells lead eventually to severe insulin deficiency. These T-cell clones are able to escape from thymus control during circumstances that yield high affinity for major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules with T-cell receptors but incorrect low affinity for self-peptides. Once released into the bloodstream, these T-cell clones can become activated to destroy self-antigens. Upon initial diagnosis, approximately ninety percent of individuals with Type I DM have elevated titers of autoantibodies (Type IA DM). The remaining ten percent of Type I DM individuals do not have serum autoantibodies and are described as having maturity-onset diabetes of the young (MODY) that can be a result of β-cell dysfunction with autosomal-dominant inheritance (Type IB DM) [71]. Other variables reported in patients with Type I DM include the presence of insulin resistance that is usually characteristic of Type 2 DM and can lead to neurological and vascular disease [72–73]. Interestingly, there is an converse overlap with Type I and Type 2 DM, since almost ten percent of Type 2 DM patients may have elevated serum autoantibodies [74].

Loss of autoimmunity in Type 1 DM can be precipitated by a number of exogenous events, such as the exposure to infectious agents [75]. In most cases but not all, the insulin gene (INS) and the human MHC or HLA complex are believed to contain the loci with IDDM1 and IDDM2 to account for the susceptibility to Type I DM with defective antigen presentation [76–77]. Interestingly, a HLA class II molecule has been linked to Type I DM inheritance. Specifically, HLA-DQ that lacks a charged aspartic acid (Asp-57) in the β-chain is believed to lead to the ineffective presentation of autoantigen peptides during thymus selection of T-cells [78]. Animal models that involve the nonobese diabetic (NOD) mice further support these findings, since these mice spontaneously develop diabetes with the human predisposing HLA-DQ corresponding molecule of H2 I-Ag. Yet, NOD mice without H2 I-Ag do not develop diabetes [79].

In contrast to Type 1 DM, Type 2 DM, also termed noninsulin-dependent diabetes mellitus (NIDDM), is characterized by insulin resistance with significant metabolic dysfunction that include obesity, impaired insulin function and secretion, and increased endogenous glucose output. Insulin resistance or defective insulin action occurs when physiological levels of insulin produce a subnormal physiologic response. Skeletal muscle and liver are two of the primary insulin-responsive organs responsible for maintaining normal glucose homeostasis. Insulin normally lowers the level of blood glucose through suppression of hepatic glucose production and stimulation of peripheral glucose uptake, but a dysfunction in any step of this process can result in insulin resistance and elevated serum glucose levels. It should be noted that although insulin resistance forms the basis for the development of Type 2 DM, elevated serum glucose levels are also a result of the concurrent impairment in insulin secretion. This abnormal insulin secretion may be a result of defective β-cell function, chronic exposure to free fatty acids and hyperglycemia, and the loss of inhibitory feedback through plasma glucagon levels [80]. Type 2 DM is the most prevalent form of diabetes and generally occurs more often in individuals over 40 years of age. The disorder is characterized by a progressive deterioration of glucose tolerance with early β-cell compensation for insulin resistance (achieved by β-cell hyperplasia) and subsequently followed by progressive decrease in β-cells mass. In contrast, gestational diabetes mellitus that represents glucose intolerance during some cases of pregnancy usually subsides after delivery.

Both diabetic cell injury and the development of insulin resistance are closely linked to the presence of cellular oxidative stress [81]. In patients with DM, elevated levels of ceruloplasmin are suggestive of increased reactive oxygen species (ROS) [82] and acute glucose fluctuations may promote oxidative stress [83]. Cellular elevated glucose levels also have been demonstrated to result in an increased production of ROS [84]. Furthermore, administration of antioxidants during elevated glucose concentrations can block free radical production and prevent the production of advanced glycation endproducts (AGEs) known to produce ROS during DM [85]. In addition, oxidative stress may more directly promote the onset of DM by decreasing insulin sensitivity and destroying the insulin-producing cells within the pancreas. For example, ROS can penetrate through cell membranes and cause damage to β-cells of pancreas [86–87]. In addition, free fatty acids which can lead to ROS, have been shown to also contribute to mitochondrial DNA damage and impaired pancreatic β-cell function [88].

Oxidative stress also is believed to modify a number of the signaling pathways within a cell that can ultimately lead to insulin resistance. In non-diabetic rats, hyperglycemia can result in a significant decrease in insulin-stimulated glucose uptake, a significant increase in muscle protein carbonyl content (used as an indicator of oxidative stress), and elevated levels of malondialdehyde and 4-hydroxynonenal as an indictor of lipid peroxidation [89]. These biological markers of oxidative stress and insulin resistance suggest that ROS contribute to the pathogenesis of hyperglycemia-induced insulin resistance [89]. Furthermore, hyperglycemia can lead to increased production of ROS in endothelial cells, liver and pancreatic β-cells [90–93]. In a model of nonobese Type 2 DM, higher levels of 8-OHdG and HNE-modified proteins in the pancreatic beta-cells of diabetic rats than in the controls were observed with levels increasing with age and fibrosis of the pancreatic islets [91]. Elevated glucose also has been shown to increase antioxidant enzyme levels in human endothelial cells, suggesting that elevated glucose levels may lead to a reparative process to protect cells from oxidative stress injury [90]. Chronic hyperglycemia is not necessary to lead to oxidative stress injury, since even short periods of hyperglycemia, generate ROS, such as in vascular cells [93]. Recent clinical correlates support these experimental studies to show that acute glucose swings in addition to chronic hyperglycemia can trigger oxidative stress mechanisms during Type 2 DM (Fig. (1)), illustrating the importance for therapeutic interventions during acute and sustained hyperglycemic episodes [83].

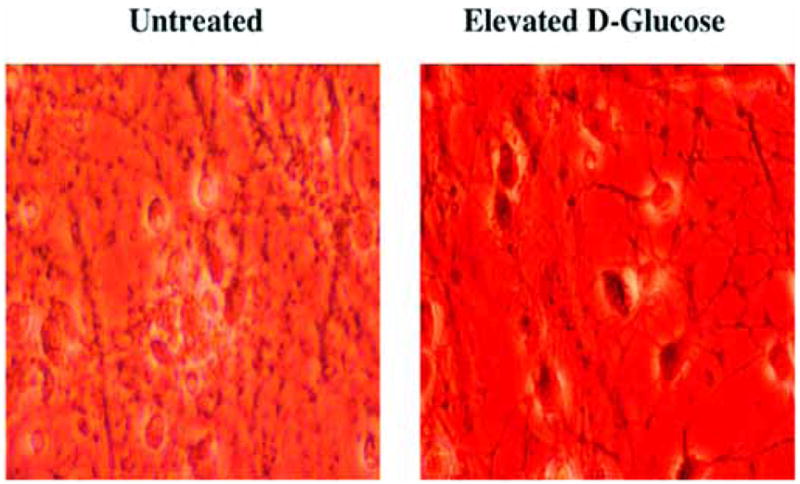

Fig. 1. Elevated glucose leads to injury in primary hippocampal neurons.

Primary hippocampal neurons were obtained from E-19 Sprague-Dawley rat pups and maintained in growth medium (Leibovitz’s L-15 medium, containing 6% sterile rat serum, 150 mM NaHCO3, 2.25 mg/ml of transferrin, 2.5 μg/ml of insulin, 10 nM progesterone, 90 μM putrescine, 15 nM selenium, 35 mM glucose, 1 mM L-glutamine, 50 μg/ml penicillin and streptomycin, and vitamins) in 35 mm polylysine/laminin-coated plates at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 and 95% room air for 10~14days. For the induction of elevated glucose, neurons were incubated in L-15 growth medium with free serum containing D-glucose at the concentration of 50 mM for 24 h at 37°C and cell survival was determined by trypan blue exclusion method. Representative images reveal trypan blue uptake in cells with elevated glucose that reflects neuronal injury.

Although the precise role of insulin resistance in cellular injury remains to be established, it has been shown at least in neurons that insulin stimulation may reverse diabetic neuropathy [94]. Interestingly, oxidative stress-induced cellular signaling may be the contributory factor responsible for cell injury that initially is set in motion following hyperglycemia. In one study, intrathecal insulin or insulin growth factor-I delivery of doses insufficient to reduce hyperglycemia significantly improved slowing of motor and sensory conduction velocity in streptozotocin (STZ) -induced diabetic rats [94]. In contrast, intrathecal saline or subcutaneous insulin did not improve conduction velocity, illustrating that reduction in cellular injury during diabetes may require targeting of specific oxidative stress cellular pathways. For example, the neuroprotective effects of insulin appear to rely upon the maintenance of mitochondrial inner membrane potential and increased ATP levels [95]. The authors used real-time whole cell fluorescence video microscopy to analyze mitochondrial inner membrane potential in cultured adult sensory neurons. Compared with control, insulin and other neurotrophic factors induced a two-fold increase in membrane potential.

DIABETES MELLITUS, CELLULAR ENERGY RESERVES, AND MITOCHONDRIAL FUNCTION

The maintenance of cellular energy reserves and intact cellular function are closely dependent upon mitochondrial biology (Fig. (2)). Oxidative stress can trigger the opening of the mitochondrial membrane permeability transition pore [19, 37, 96–97] and lead to a significant loss of mitochondrial NAD+ stores and subsequent apoptotic cell injury [98–99]. In addition, mitochondria are a significant source of superoxide radicals that are associated with oxidative stress [100]. Blockade of the electron transfer chain at the flavin mononucleotide group of complex I (NADPH ubiquinone oxidoreductase) or at the ubiquinone site of complex in (ubiquinone-cytochrome c reductase) results in the active generation of free radicals which can impair mitochondrial electron transport and enhance free radical production [101–102]. Furthermore, mutations in the mitochondrial genome have been associated with the potential development of a host of disorders, such as hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, and hypomagnesemia [5, 103]. Reactive oxygen species also may lead to the induction of acidosis-induced cellular toxicity [4] and subsequent mitochondrial failure [104]. Disorders, such as hypoxia [105], diabetes [106–107], and oxidative stress [108–110] can result in the disturbance of intracellular pH. In addition, modulation of intracellular pH is necessary for endonuclease activity during cell injury [27, 109–110].

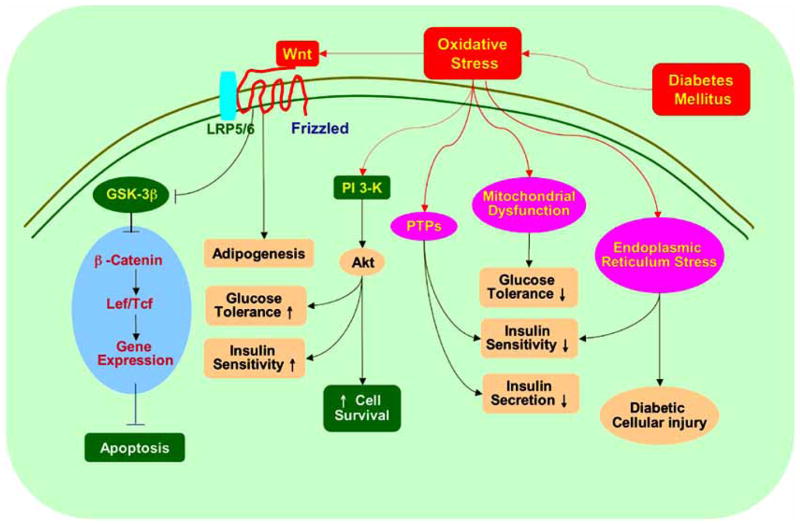

Fig. 2. Diabetes mellitus integrates with a host of cellular pathways controlled by oxidative stress.

Cellular injury during diabetes mellitus employs a series of pathways of oxidative stress that involve mitochondrial dysfunction, G-protein signaling, PTPs, Wnt, the serine-threonine kinase Akt, and its downstream substrates of GSK-3β and FOXO3a that can impact upon glucose tolerance, insulin sensitivity, and insulin secretion.

Proper cellular function during diabetes requires the maintenance of mitochondrial membrane potential, since mitochondrial dysfunction plays a role in the development of diabetes and insulin resistance [81]. In patients with Type 2 DM, both ADH:O(2) oxidoreductase activity and citrate synthase activity can be depressed. In addition, skeletal muscle mitochondria have been described to be smaller than those in control subjects [111]. Furthermore, a decrease in the levels of mitochondrial proteins and mitochondrial DNA in adipocytes has been correlated with the development of Type 2 DM [112]. Insulin resistance in the elderly also has been associated with elevation in fat accumulation and reduction in mitochondrial oxidative and phosphorylation activity [113]. In addition, an association exists with insulin resistance and the impairment of intramyocellular fatty acid metabolism in young insulin-resistance offspring of parents with Type 2 DM [114].

In addition to the necessity of the normal function for mitochondria in general, uncoupling proteins (UCPs) can play a significant role during diabetes. UCPs are a family of carrier proteins in the inner membrane of mitochondria that uncouple oxygen consumption in the respiratory chain from ATP synthesis. They catalyze an inducible proton conductance and disperse the proton electrochemical potential gradient across the mitochondrial inner membrane [115]. This uncoupling of respiration results in the activation of substrate oxidation and dissipation of oxidation energy as heat instead of ATP. In addition, mild uncoupling of respiration may play a significant role in regulating ATP synthesis, and fatty acids and glucose oxidation. Members of UCP family include UCP-1, 2,3,4,5 in mammals [116] and are distinctly distributed among different tissues. UCP-1 and UCP-4 are exclusively expressed in brown adipose tissue and in the brain, respectively. UCP-2 is expressed in most tissues while UCP-5 is present in multiple tissues with an especially high level in the brain and testis. UCP-3 is expressed predominantly in skeletal muscle.

UCP-1 is important for controlling the dissipation of oxidation energy as heat. Overexpression of UCP-1 is potentially beneficial for diabetes by reducing excessive energy in obesity. Muscle-specific Overexpression of UCP in skeletal muscle has been shown to increase energy expenditure and enhance insulin action to protect against high-fat diet induced insulin resistance [117]. In addition, expression of UCP-1 in skeletal results in muscle respiratory uncoupling that reverses insulin resistance [118]. Similar beneficial effects also were observed in specific overexpression of UCP-1 in white adipose tissues [119].

Uncoupling protein 2 (UCP-2) and uncoupling protein 3 (UCP-3) are expressed in tissues important for thermogenesis and/or in substrate oxidation, such as adipose tissue and skeletal muscles. UCP-2 is a member of the multigenic UCP family that is expressed in a wide range of tissues and organs. Possible functions of UCP-2 include control of ATP synthesis, regulation of fatty acid metabolism and control of reactive oxygen species production. UCP-2 expression in tissues involved in lipid and energy metabolism and mapping of the gene to a region linked to obesity and hyperinsulinemia has furthered investigations with UCP-2 and diabetes. In human adipose tissue and skeletal muscle, UCP-2 expression is increased during fasting and has been shown to be under the control of fatty acids and thyroid hormones. Interestingly, overexpression of UCP-2 in isolated pancreatic islets results in decreased ATP content and blunted glucose-stimulated insulin secretion while UCP-2-deficient mice show an increased ATP level and an enhanced insulin secretion. In ob/ob mice lacking UCP-2, insulin secretion is dramatically improved with decreased levels of glycemia [120]. Yet, it is important to note that overexpression of UCP-2 may protect beta-cells during hydrogen peroxide toxicity and oxidative stress [121]. It is of note that elevated expression of UCP-2 also was reported to exert substantial negative regulation of β-cell insulin secretion and contribute to the impairment of β-cell function [122]. A role for UCP-3 in carbohydrate metabolism and in Type 2 DM also has been suggested. Mice overexpressing UCP-3 in skeletal muscle showed reduced fasting plasma glucose levels, improved glucose tolerance after an oral glucose load, and reduced fasting plasma insulin levels. In addition, UCP-3 levels have been shown to be at least twice as low in patients with Type 2 DM when compared with controls, suggesting a role for UCP-3 in glucose homeostasis [123]. In addition, UCP-3 may function to facilitate fatty acid oxidation and minimize ROS production [124].

Endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress also is a component of diabetic cellular injury and peripheral insulin resistance. ER stress is characterized by the accumulation of unfolded proteins in the lumen of the ER [125]. It is associated with an unfolded protein response (UPR) or by excessive protein trafficking that may be triggered by events such as viremia. UPR regulates ER function and functions to coordinate the activity and participation of the processing and degradation pathways for unfolded proteins [126]. Obesity is associated with induction of ER stress predominantly in liver and adipose tissues. Under hyperglycemic conditions, the production of glucosamine by hexosamine pathway may initiate ER stress. This process can promote a c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK)-dependent serine phosphorylation of insulin receptor substrate 1 (IRS-1), which results in suppression of insulin-receptor signaling pathway. In addition, the absence of X-box-binding protein-1 (XBP-1), a transcription factor that modulates the ER stress response, promotes insulin resistance [127]. Furthermore, gene silencing of oxygen-regulated protein 150 (ORP150), a molecular chaperone resident in the ER, has been shown to promote insulin resistance in non-diabetic control mice. In contrast, overexpression of ORP150 significantly decreases insulin resistance and markedly improves glycemic control in the liver of obese diabetic mice. Although not entirely clear, these observations may be associated with phosphorylation state of IRS-1 and protein kinase B (Akt) as well as the expression levels of phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase and glucose-6-phosphatase [128].

DIABETES MELLITUS, G-PROTEIN SIGNALING, AND PROTEIN-TYROSINE PHOSPHATASES

Metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluRs) are coupled to signal transduction systems through GTP-proteins (G-proteins) [6]. Given the ubiquitous distribution of these receptors, the mGluR system impacts upon neuronal, vascular [129–131], and inflammatory cell function [132–133] and drives a spectrum of cellular pathways that involve protein kinases, endonucleases, cellular acidity, energy metabolism, mitochondrial membrane potential, caspases, and specific mitogen-activated protein kinases. The expression of mGluRs throughout mammalian organ systems places these receptors as essential mediators not only for the initial development of an organism, but also for the vital determination of a cell's fate during many disorders including DM. In animal models of diabetes, the expression of mGluR1 and mGluR5 messenger RNA are significantly increased in all layers of the dorsal horn of the spinal cord, suggesting that mGluR expression and activity may be associated with the development of diabetic neuropathy [134]. In addition, mGluRs are expressed in pancreatic islet cells and can impact upon the release of glucagon release. For example, the mGlu8 receptor is present in glucagon-secreting alpha-cells and intrapancreatic neurons and functions to inhibit glucagon release [135].

Protein-tyrosine phosphatases (PTPs) play a variety of roles in cellular signaling transduction as well as in pathological processes [44, 136–137]. The PTPs can be divided into four groups based on their amino acid sequence in the catalytic domain. Class I, II, and III are cysteine-based PTPs and Class IV is an aspartate-based PTP. Among Class I PTPs, 38 members have been identified in the human genome and some of these members have been linked to type 2 diabetes mellitus and clinical cancer susceptibility [138]. The classical PTPs are strictly tyrosine specific. They are subdivided into the receptor-like PTPs (RPTPs) and the non-receptor-like PTPs (NRPTPs) or cytosolic PTPs. The RPTPs exist in plasma membranes while the NRPTPs occupy intracellular compartments [139–140].

In DM, PTPs function as a negative regulator of insulin signal transduction (Fig. (2)). Generation of myocytes with a PTP1B homozygous deletion demonstrate enhanced insulin-dependent activation of insulin receptor autophosphorylation, tyrosine phosphorylation of insulin receptor substrates, activation of protein kinase B (Akt), and increased insulin sensitivity [141]. Inhibition of PTP1B activity through exercise in diet-induced obesity in rats also improved insulin sensitivity [142]. In addition, it has been shown that knockdown of PTPMT1 ((PTP localized to the Mitochondrion 1) expression in pancreatic insulinoma cell lines significantly enhances both ATP production and insulin secretion [143]. In regards to PTP2 or SHP-2, SHP-2 similar to PTP1B has been found to have increased expression in the liver and skeletal muscle of streptozotocin-diabetic rats with an increased ratio of particulate to cytosol distribution in diabetic tissue that could be reversed after insulin treatment, suggesting that these PTPs have a role in the pathogenesis of insulin resistance and DM [144].

DIABETES MELLITUS, WNT PROTEINS, AND PHOSPHATIDYLINOSITOL 3-KINASE PATHWAYS

Wnt proteins, derived from the Drosophila Wingless (Wg) and the mouse Int-1 genes, are divided into two functional classes based on their ability to induce a secondary body axis in Xenopus embryos and to activate certain signaling cascades that consist of the Wnt1 class and the Wnt5a class [145]. These proteins are secreted cysteine-rich glycosylated proteins that play a role in a variety of cellular functions that involve embryonic cell proliferation, differentiation, survival, and death [29, 146–147]. The members of the Wnt1 class lead to a secondary body axis in Xenopus and include Wnt1, Wnt2, Wnt3, Wnt3a, Wnt8 and Wnt8a. Wnt proteins of this class facilitate activation of the Frizzled transmembrane receptor and the co-receptor lipoprotein related protein 5 and 6 (LRP-5/6). This leads to the activation of the typical canonical Wnt/β-catenin pathway. The Wnt5a class cannot induce secondary axis formation in Xenopus and includes the Wnt proteins of Wnt4, Wnt5a, Wnt5b, Wnt6, Wnt7a and Wnt11. These Wnt proteins bind the Frizzled transmembrane receptor to activate heterotrimeric G proteins and increase intracellular calcium levels.

Wnt signaling involves both canonical and non-canonical pathways. The canonical Wnt signaling pathway involves Wnt1, Wnt3a, and Wnt8 and functions through β-catenin-dependent pathways. The non-canonical pathway involves intracellular calcium signaling and consists primarily of Wnt4, Wnt5a, and Wnt11. This Wnt-calcium pathway employs not only calcium signaling, but also the planar cell polarity pathway [146, 148–149]. In general, all Wnt signaling pathways are initiated by interaction of Wnt proteins with Frizzled receptors, but in this pathway, Wnt signaling only will be activated if the binding of the Wnt protein to the Frizzled transmembrane receptor takes place in the presence of the co-receptor LRP-5/6 resulting in the formation of a Wnt-Frizzled-LRP5/6 trimolecular complex [150]. Once Wnt protein binds to the Frizzled transmembrane receptor and the co-receptor LRP-5/6, this is followed by recruitment of Dishevelled, a cytoplasmic multifunctional phosphoprotein.

Interestingly, the Wnt-Frizzled signaling pathway can prevent cell injury through a variety of mechanisms. Wnt prevents apoptosis through β-catenin/Tcf transcription mediated pathways [151]. Overexpression of exogenous Wnt results in the protection of cells against c-myc induced apoptosis through induction of β-catenin, cyclooxygenase-2, and Wnt induced secreted protein [152]. Wnt signaling also can inhibit apoptosis during oxidative stress [145] and β-amyloid toxicity that may require modulation of glycogen synthase kinase-3β (GSK-3β) and β-catenin [153].

Recent work suggests that variations in genes in the Wnt signaling, such as transcription factor 7-like 2 gene, may impart increased risk for Type 2 DM in some populations [154–156] as well as have increased association with obesity, such as LRP-5 [157] (Fig. (2)). In addition, mice that overexpress Wnt10b have been shown to be more glucose tolerant and insulin sensitive [158]. Prior studies also noted the expression of Wnt5b in adipose tissue, the pancreas, and the liver in diabetic patients with potential regulation of adipose cell function [159]. In cell culture studies, overexpression of Wnt4 or Wnt5a prevented injury to glomerular mesangial cells during high glucose stress [160].

Closely linked to Wnt is GSK-3β. In the Wnt pathway, dishevelled is phosphorylated by casein kinase Iε to form a complex with Frat1 and inhibit GSK-3β activity. Inhibition of GSK-3β activity can increase cell survival during oxidative stress and, as a result, GSK-3β is considered to be a therapeutic target for some neurodegenerative disorders [1, 161–163]. GSK-3β also may to influence inflammatory cell survival [28] and activation [164]. In regards to DM, inactivation of GSK-3β by small molecule inhibitors or RNA interference prevents toxicity from high concentrations of glucose and increases rat beta cell replication, suggesting a possible target of GSK-3β for pancreatic beta cell regeneration [165]. Furthermore, pharmacologic inhibition of GSK-3β by recombinant Wnt5a or other agents prevents high glucose-mediated apoptosis in glomerular mesangial cells [160]. In clinical studies, physical exercise is one of the important lifestyle interventions for DM. Exercise results in pronounced improvement in glycemic control usually over relatively short of time [166]. At the cellular level, physical exercise has been shown to phosphorylate and inhibit GSK-3β activity [167].

Oxidative stress and free radical production also have been implicated in insulin resistance during DM and involve impairment of phosphoinositide 3 kinase (PI 3-K) activity and Akt [168] (Fig. (2)). Also known as protein kinase B [7, 169], Akt has three family members that are PKBα or Akt1, PKBβ or Akt2, and PKBγ or Akt3 [170–171]. Insulin controls glucose transport through insulin receptor substrate-1 (IRS-1) and in part through Akt as well as atypical protein kinase C. Perturbations in this pathway can substantially alter hepatic glucose output and triglyceride release [172]. Akt signaling also is tied to insulin sensitivity in diabetes. In response to insulin, Akt leads to glucose uptake in adipocytes through its stimulation of glucose transporter 4 (GLUT-4) translocation and increased synthesis of GLUT-1 [173]. The elevated glucose influx is accompanied by increased lipid synthesis and decreased glycogen synthesis. Conversely, loss of Akt kinase activity is accompanied by impairment in insulin-stimulated glucose transport in muscle and adipocytes both from obese rats and patients with diabetes [174–175] and leads to impaired glucose tolerance and diabetes [176]. In addition, mutations in Akt2 are linked to the development of severe insulin resistance and diabetes [177].

Akt also is considered a central modulator to prevent apoptotic cell injury during late genomic DNA destruction and early apoptotic signaling with membrane phosphatidylserine (PS) exposure [4, 62]. Increased Akt activity can foster cell survival during free radical exposure [36, 178], matrix detachment [179], neuronal axotomy [180], DNA damage [43, 181–183], anti-Fas antibody administration [184], oxidative stress [19, 36, 183, 185], hypoxic preconditioning [186], B-amyloid (AB) exposure [187], metabotropic receptor signaling [6, 132–133], and cell metabolic pathways [98–99]. Activation of Akt also can prevent membrane PS exposure on injured cells [181, 188] and block the activation of microglia during oxidative stress [19, 132, 183].

In addition, modulation of Akt activity can critically affect cell survival during hyperglycemia and the outcome of DM complications. During chronic hyperglycemic stress, inhibition of Akt leads to increased endothelial cell injury [189]. In STZ diabetic rats, vascular control and integrity [190] as well as mitochondrial function [191] can be rectified during activation of Akt. Furthermore, ER stress inducers can lead to dephosphorylation and inactivation of Akt with subsequent cell death [192]. On the converse side, overexpression of Akt, such as in endothelial cells, can protect cells from injury during elevated glucose concentrations [193].

Given the therapeutic potential of targeting Akt to treat DM and diabetic complications, recent studies highlight several considerations for targeting Akt activity. In regards to physical exercise which has been shown to be beneficial upon glycemic control, weight loss and insulin resistance, Akt phosphorylation and activity has been shown to be increased in the immediate periods following acute exercise [167]. Combined with the benefits of exercise, erythropoietin (EPO) may represent another consideration for diabetic therapeutic strategies. EPO is a trophic factor that is approved by the Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of anemia, but a body of recent work has revealed that EPO is not required only for erythropoiesis and that EPO and its receptor exist in other organs and tissues outside of the liver and the kidney, such as the brain and heart. As a result, EPO has been identified as a possible candidate for several disorders that involve both cardiac and nervous system diseases [194–195]. Interestingly, EPO leads to the phosphorylation of Akt. Once activated, Akt can confer protection against genomic DNA degradation and membrane PS exposure [19, 43, 186]. Up-regulation of Akt activity during injury paradigms, such as N-methyl-D-aspartate toxicity [196], cardiomyocyte ischemia [197], hypoxia [43], and oxidative stress [36, 37, 198], is vital for EPO protection, since prevention of Akt phosphorylation blocks cellular protection and anti-inflammatory mechanisms by EPO [36–37, 198]. EPO employs the Akt pathway to prevent apoptosis by maintaining mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm), preventing the cellular release of cytochrome c, and modulating caspase activity [36–37, 43].

In clinical studies with DM, plasma EPO is often low in diabetic patients with [199] or without anemia [200]. In these diabetic patients, levels of EPO appear to be determined by hemoglobin levels and degree of microalbuminuria [199]. In addition, the failure to produce erythropoietin in response to a declining hemoglobin level represents an impaired EPO response in diabetic patients [201]. In light of the ability of EPO to modulate Akt activity and provide cellular protection during oxidative stress, EPO may be efficacious in patients with diabetes. Investigations involving subcutaneous EPO in diabetics and non-diabetics with severe, resistant congestive heart failure have shown to decrease fatigue, increase left ventricular ejection fraction, and significantly decrease the number of hospitalization days [202]. Yet, one must be cautious with the introduction of even known therapies for new applications. Some studies suggest that elevated plasma levels of EPO independent of hemoglobin concentration can have a poor prognostic value in individuals with congestive heart failure [203]. The use of EPO in patients with uncontrolled hypertension is contraindicated, since both acute and long-term administration of EPO can precipitate hypertensive emergencies. Maintenance treatment with EPO in cancer patients receiving chemotherapy has been associated with nonfatal myocardial infarction, vascular thrombosis, pyrexia, vomiting, shortness of breath, paresthesias, and upper respiratory tract infection [204–205].

Interestingly, EPO may require other substrates of the Akt1 pathway, such as nuclear factor-κB [206–208], caspase 9 [37], and the Forkhead transcription factor FOXO3a [209] to oversee cell viability. The mammalian Forkhead transcription factor family regulates processes ranging from cell longevity to cell apoptosis [1, 210–211] and may be involved in pathways responsible for cell metabolism, DM onset, and diabetic complications. In a prospective population based study of 1245 participants aged 85 years or more, haplotype analyses of FOXO1a revealed that carriers of haplotype 3 ‘TCA’ had higher HbA1c levels to suggest evidence of at least disorders with glucose intolerance [212]. Other work suggests that the Forkhead proteins may confer resistance against oxidative stress for some cell populations, such as hematopoietic stem cells [213]. In particular for FOXO1, this transcription factor may be responsible for the prevention of beta cell injury during against oxidative stress. This process requires the complex formation with the promyelocytic leukemia protein Pml and the NAD-dependent deacetylase Sirt1 to activate expression of the insulin2 gene transcription factors NeuroD and MafA [214]. Yet, the role of Forkhead transcription factors can vary among different cells and tissues. For example, mice overexpressing FOXO1 in skeletal muscle suffered from reduced skeletal muscle mass and poor glycemic control [215].

CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE PERSPECTIVES

DM is a significant healthcare concern worldwide that affects more than 165 million individuals. More importantly, and by the year 2030, it is believed that greater than 360 million individuals will be afflicted with DM and its debilitating conditions. Oxidative stress forms the foundation for the induction of multiple cellular pathways that can ultimately lead to cellular injury during DM. In particular, novel pathways that involve metabotropic receptor signaling, protein-tyrosine phosphatases, Wnt proteins, Akt, GSK-3β, and forkhead transcription factors may be responsible for the onset and progression of complications from DM. Integration of these pathways into therapeutic regiments can shed new light upon drug development, such as for EPO [216–217]. As we acquire new knowledge into the complexities of DM that lead to cell injury, especially in the nervous system, we will be able to forge new treatments for the ill effects of DM.

Table 1.

Integrated Cellular Signaling Pathways of Diabetes Mellitus and Oxidative Stress

| Cellular Pathway in Diabetes Mellitus and Oxidative Stress | Biological Response | Selected References |

|---|---|---|

| Mitochondrial dysfunction | ||

| NADH:O(2) Oxidoreductase activity decreased in skeletal muscle | Dysregulation of oxidation of both carbohydrate and lipid, contributing to the development of DM (Type 2) | [111] |

| Mitochondrial protein and DNA decreased in adipocytes | Contributes to the development of DM (Type 2) | [112] |

| Reduction in mitochondrial oxidative and phosphorylation activity | Increases insulin resistance | [113] |

| Uncoupling protein 1 expression in skeletal muscle | Reverses insulin resistance | [118] |

| Uncoupling protein 2 expression in pancreatic islet cells | Decreases insulin secretion | [122] |

| Uncoupling protein 3 deficiency in DM (type 2) patients | Decreases glucose tolerance | [123] |

| Endoplasmic reticulum stress | Induces diabetic cellular injury Increases Insulin resistance | [127] |

| Metabotropic glutamate receptor (mGluR) Expression of mGluR1 and mGluR5 in dorsal horn of spinal cord | Diabetic neuropathy | [134] |

| Expression of mGluR8 in pancreatic islet cells | Inhibits glucagon release | [135] |

| Protein-tyrosine phosphatases (PTPs) | ||

| PTP1B in myocytes | Decreases insulin sensitivity | [141] |

| PTPMT1 in pancreatic insulinoma | Decreases ATP production and insulin secretion | [144] |

| Wnt signaling pathway | ||

| Wnt5b in adipose tissue | Promotes adipogenesis | [159] |

| Wnt10b expression in mice | Increases glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity | [158] |

| GSK-3β activation | β-Cell degeneration | [165] |

| Akt activation | Increases glucose uptake induced by insulin | [173] |

| Prevents chronic hyperglycemic stress induced cell injury | [189,193] | |

| Increases glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity | [176, 177] | |

Note: DM: Diabetes mellitus; GSK-3β: Glycogen synthase kinase-3β; PTPMT1: PTP localized to mitochondrion 1.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the following grants (KM): American Diabetes Association, American Heart Association (National), Bugher Foundation Award, Janssen Neuroscience Award, LEARN Foundation Award, MI Life Sciences Challenge Award, Nelson Foundation Award, NIH NIEHS (P30 ES06639), NIH NINDS, and NIH NIA.

References

- 1.Chong ZZ, Li F, Maiese K. Prog Neurobiol. 2005;75:207. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2005.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fubini B, Hubbard A. Free Radic Biol Med. 2003;34:1507. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(03)00149-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pfeiffer S, Lass A, Schmidt K, Mayer B. FASEB J. 2001;15:2355. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0295com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chong ZZ, Li F, Maiese K. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2005;49:1. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2004.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li F, Chong ZZ, Maiese K. Curr Med Chem. 2006;13:883. doi: 10.2174/092986706776361058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maiese K, Chong ZZ, Li F. Curr Neurovasc Res. 2005;2:425. doi: 10.2174/156720205774962692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chong ZZ, Kang JQ, Maiese K. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2004;6:277. doi: 10.1089/152308604322899341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ferretti P. Curr Neurovasc Res. 2004;1:215. doi: 10.2174/1567202043362397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Han HS, Suk K. Curr Neurovasc Res. 2005;2:409. doi: 10.2174/156720205774962647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koyama R, Ikegaya Y. Curr Neurovasc Res. 2004;1:3. doi: 10.2174/1567202043480242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li F, Chong ZZ, Maiese K. Neurosignals. 2004;13:265. doi: 10.1159/000081963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hong JR, Lin GH, Lin CJ, Wang WP, Lee CC, Lin TL, Wu JL. Development. 2004;131:5417. doi: 10.1242/dev.01409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lin SH, Maiese K. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2001;21:262. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200103000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li F, Chong ZZ, Maiese K. Front Biosci. 2004;9:2500. doi: 10.2741/1412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leytin V, Allen DJ, Mykhaylov S, Lyubimov E, Freedman J. J Thromb Haemost. 2006;4:2656. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2006.02200.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maiese K, Vincent AM. J Neurosci Res. 2000;59:568. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(20000215)59:4<568::AID-JNR13>3.0.CO;2-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dombroski D, Balasubramanian K, Schroit AJ. J Autoimmun. 2000;14:221. doi: 10.1006/jaut.2000.0365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jessel R, Haertel S, Socaciu C, Tykhonova S, Diehl HA. J Cell Mol Med. 2002;6:82. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2002.tb00313.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kang JQ, Chong ZZ, Maiese K. Mol Pharmacol. 2003;64:557. doi: 10.1124/mol.64.3.557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Torriglia A, Chaudun E, Courtois Y, Counis MF. Biochimie. 1997;79:435. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9084(97)86153-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sun XM, Cohen GM. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:14857. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weber JT. Curr Neurovasc Res. 2004;1:151. doi: 10.2174/1567202043480134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Madaio MP, Fabbi M, Tiso M, Daga A, Puccetti A. Eur J Immunol. 1996;26:3035. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830261232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Torriglia A, Chaudun E, Chany-Fournier F, Jeanny JC, Courtois Y, Counis MF. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:28579. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.48.28579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Montague JW, Hughes F, Jr, Cidlowski JA. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:6677. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.10.6677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pandey S, Walker PR, Sikorska M. Biochemistry. 1997;36:711. doi: 10.1021/bi962387h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vincent AM, Maiese K. Exp Cell Res. 1999;246:290. doi: 10.1006/excr.1998.4282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chong ZZ, Li F, Maiese K. Int J Mol Med. 2007;19:263. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li F, Chong ZZ, Maiese K. Histol Histopathol. 2006;21:103. doi: 10.14670/hh-21.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Siu AW, To CH. Clin Exp Optom. 2002;85:378. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mukherjee PK, Marcheselli VL, Serhan CN, Bazan NG. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:8491. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402531101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Adams S, Green P, Claxton R, Simcox S, Williams MV, Walsh K, Leeuwenburgh C. Front Biosci. 2001;6:A17. doi: 10.2741/adams. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yamamoto T, Maruyama W, Kato Y, Yi H, Shamoto-Nagai M, Tanaka M, Sato Y, Naoi M. J Neural Transm. 2002;109:1. doi: 10.1007/s702-002-8232-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Goldshmit Y, Erlich S, Pinkas-Kramarski R. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:46379. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105637200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pugazhenthi S, Nesterova A, Jambal P, Audesirk G, Kern M, Cabell L, Eves E, Rosner MR, Boxer LM, Reusch JE. J Neurochem. 2003;84:982. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01606.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chong ZZ, Kang JQ, Maiese K. Br J Pharmacol. 2003;138:1107. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chong ZZ, Kang JQ, Maiese K. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2003;23:320. doi: 10.1097/01.WCB.0000050061.57184.AE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Witting A, Muller P, Herrmann A, Kettenmann H, Nolte C. J Neurochem. 2000;75:1060. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0751060.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vincent AM, Maiese K. J Histochem Cytochem. 1999;47:661. doi: 10.1177/002215549904700508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sharma SK, Ebadi M. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2003;5:251. doi: 10.1089/152308603322110832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.de la Monte SM, Chiche J, von dem Bussche A, Sanyal S, Lahousse SA, Janssens SP, Bloch KD. Lab Invest. 2003;83:287. doi: 10.1097/01.lab.0000056995.07053.c0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang JY, Shum AY, Ho YJ. J Neurosci Res. 2003;72:508. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chong ZZ, Kang JQ, Maiese K. Circulation. 2002;106:2973. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000039103.58920.1f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chong ZZ, Lin SH, Kang JQ, Maiese K. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2003;23:561. doi: 10.1023/A:1025158314016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Salinas M, Diaz R, Abraham NG, Ruiz de Galarreta CM, Cuadrado A. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:13898. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209164200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Quinn L. Nurs Clin North Am. 2001;36:175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wild S, Roglic G, Green A, Sicree R, King H. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:1047. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.5.1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Laakso M. J Intern Med. 2001;249:225. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2796.2001.00789.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Daneman D. Lancet. 2006;367:847. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68341-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Awad N, Gagnon M, Messier C. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2004;26:1044. doi: 10.1080/13803390490514875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gerozissis K. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2003;23:1. doi: 10.1023/A:1022598900246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Perkins BA, Bril V. Curr Diab Rep. 2002;2:495. doi: 10.1007/s11892-002-0119-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ott A, Stolk RP, van Harskamp F, Pols HA, Hofman A, Breteler MM. Neurology. 1999;53:1937. doi: 10.1212/wnl.53.9.1937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schnaider Beeri M, Goldbourt U, Silverman JM, Noy S, Schmeidler J, Ravona-Springer R, Sverdlick A, Davidson M. Neurology. 2004;63:1902. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000144278.79488.dd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Xu WL, Qiu CX, Wahlin A, Winblad B, Fratiglioni L. Neurology. 2004;63:1181. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000140291.86406.d1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Beeri MS, Silverman JM, Davis KL, Marin D, Grossman HZ, Schmeidler J, Purohit DP, Perl DP, Davidson M, Mohs RC, Haroutunian V. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2005;60:471. doi: 10.1093/gerona/60.4.471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Luchsinger JA, Tang MX, Stern Y, Shea S, Mayeux R. Am J Epidemiol. 2001;154:635. doi: 10.1093/aje/154.7.635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Steen E, Terry BM, Rivera EJ, Cannon JL, Neely TR, Tavares R, Xu XJ, Wands JR, de la Monte SM. J Alzheimers Dis. 2005;7:63. doi: 10.3233/jad-2005-7107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Schubert M, Gautam D, Surjo D, Ueki K, Baudler S, Schubert D, Kondo T, Alber J, Galldiks N, Kustermann E, Arndt S, Jacobs AH, Krone W, Kahn CR, Bruning JC. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:3100. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308724101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Harris MI, Eastman RC. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2000;16:230. doi: 10.1002/1520-7560(2000)9999:9999<::aid-dmrr122>3.0.co;2-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Maciejewski ML, Maynard C. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(Suppl 2):B69. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.suppl_2.b69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Maiese K, Chong ZZ. Restor Neurol Neurosci. 2004;22:87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.McCormick WC, Hardy J, Kukull WA, Bowen JD, Teri L, Zitzer S, Larson EB. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49:1156. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.49231.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mendiondo MS, Kryscio RJ, Schmitt FA. Neurology. 2001;57:943. doi: 10.1212/wnl.57.6.943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bonner-Weir S. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2000;11:375. doi: 10.1016/s1043-2760(00)00305-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bottino R, Trucco M. Diabetes. 2005;54(Suppl 2):S79. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.suppl_2.s79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Davies JL, Kawaguchi Y, Bennett ST, Copeman JB, Cordell HJ, Pritchard LE, Reed PW, Gough SC, Jenkins SC, Palmer SM, Balfour KM, Rowe BR, Farrall M, Barnett AH, Bain SC, Todd JA. Nature. 1994;371:130. doi: 10.1038/371130a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kyvik KO, Green A, Beck-Nielsen H. BMJ. 1995;311:913. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.7010.913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Melanitou E. Clin Immunol. 2005;117:195. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2005.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Redondo MJ, Yu L, Hawa M, Mackenzie T, Pyke DA, Eisenbarth GS, Leslie RD. Diabetologia. 2001;44:354. doi: 10.1007/s001250051626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Permutt MA, Wasson J, Cox N. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:1431. doi: 10.1172/JCI24758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kernan WN, Inzucchi SE, Viscoli CM, Brass LM, Bravata DM, Horwitz RI. Neurology. 2002;59:809. doi: 10.1212/wnl.59.6.809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Orchard TJ, Olson JC, Erbey JR, Williams K, Forrest KY, Smithline Kinder L, Ellis D, Becker DJ. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:1374. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.5.1374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Pietropaolo M, Barinas-Mitchell E, Pietropaolo SL, Kuller LH, Trucco M. Diabetes. 2000;49:32. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.49.1.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Luppi P, Rossiello MR, Faas S, Trucco M. J Mol Med. 1995;73:381. doi: 10.1007/BF00240137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Awata T, Kurihara S, Kikuchi C, Takei S, Inoue I, Ishii C, Takahashi K, Negishi K, Yoshida Y, Hagura R, Kanazawa Y, Kalayama S. Diabetes. 1997;46:1637. doi: 10.2337/diacare.46.10.1637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Baisch JM, Weeks T, Giles R, Hoover M, Stastny P, Capra JD. N Engl J Med. 1990;322:1836. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199006283222602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Todd JA, Bell JI, McDevitt HO. Nature. 1987;329:599. doi: 10.1038/329599a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lund T, O’Reilly L, Hutchings P, Kanagawa O, Simpson E, Gravely R, Chandler P, Dyson J, Picard JK, Edwards A, Kioussis D, Cooke A. Nature. 1990;345:727. doi: 10.1038/345727a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Del Prato S, Marchetti P. Horm Metab Res. 2004;36:775. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-826163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Maiese K, Morhan SD, Chong ZZ. Curr Neurovasc Res. 2007;4:63. doi: 10.2174/156720207779940653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Memisogullari R, Bakan E. J Diabetes Complicat. 2004;18:193. doi: 10.1016/S1056-8727(03)00032-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Monnier L, Mas E, Ginet C, Michel F, Villon L, Cristol JP, Colette C. JAMA. 2006;295:1681. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.14.1681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Giugliano D, Ceriello A, Paolisso G. Diabetes Care. 1996;19:257. doi: 10.2337/diacare.19.3.257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Giardino I, Edelstein D, Brownlee M. J Clin Invest. 1996;97:1422. doi: 10.1172/JCI118563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Chen H, Li X, Epstein PN. Diabetes. 2005;54:1437. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.5.1437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Lepore DA, Shinkel TA, Fisicaro N, Mysore TB, Johnson LE, d’Apice AJ, Cowan PJ. Xenotransplantation. 2004;11:53. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3089.2004.00082.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Rachek LI, Thornley NP, Grishko VI, LeDoux SP, Wilson GL. Diabetes. 2006;55:1022. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.55.04.06.db05-0865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Haber CA, Lam TK, Yu Z, Gupta N, Goh T, Bogdanovic E, Giacca A, Fantus IG. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2003;285:E744. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00355.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Ceriello A, dello Russo P, Amstad P, Cerutti P. Diabetes. 1996;45:471. doi: 10.2337/diab.45.4.471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Ihara Y, Toyokuni S, Uchida K, Odaka H, Tanaka T, Ikeda H, Hiai H, Seino Y, Yamada Y. Diabetes. 1999;48:927. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.48.4.927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Ling PR, Mueller C, Smith RJ, Bistrian BR. Metabolism. 2003;52:868. doi: 10.1016/s0026-0495(03)00057-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Yano M, Hasegawa G, Ishii M, Yamasaki M, Fukui M, Nakamura N, Yoshikawa T. Redox Rep. 2004;9:111. doi: 10.1179/135100004225004779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Brussee V, Cunningham FA, Zochodne DW. Diabetes. 2004;53:1824. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.7.1824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Huang TJ, Verkhratsky A, Fernyhough P. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2005;28:42. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2004.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Di Lisa F, Menabo R, Canton M, Barile M, Bernardi P. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:2571. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006825200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Lin SH, Vincent A, Shaw T, Maynard KI, Maiese K. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2000;20:1380. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200009000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Maiese K, Chong ZZ. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2003;24:228. doi: 10.1016/S0165-6147(03)00078-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Chong ZZ, Lin SH, Li F, Maiese K. Curr Neurovasc Res. 2005;2:271. doi: 10.2174/156720205774322584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Chong ZZ, Li FQ, Maiese K. Curr Neurovasc Res. 2005;2:55. doi: 10.2174/1567202052773508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Liu Y, Fiskum G, Schubert D. J Neurochem. 2002;80:780. doi: 10.1046/j.0022-3042.2002.00744.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Turrens JF, Alexandre A, Lehninger AL. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1985;237:408. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(85)90293-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Wilson FH, Hariri A, Farhi A, Zhao H, Petersen KF, Toka HR, Nelson-Williams C, Raja KM, Kashgarian M, Shulman GI, Scheinman SJ, Lifton RP. Science. 2004;306:1190. doi: 10.1126/science.1102521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Sensi SL, Jeng JM. Curr Mol Med. 2004;4:87. doi: 10.2174/1566524043479211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Roberts E, Jr, Chih CP. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1997;17:560. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199705000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Cardella F. Acta Biomed. 2005;76(Suppl 3):49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Kratzsch J, Knerr I, Galler A, Kapellen T, Raile K, Korner A, Thiery J, Dotsch J, Kiess W. Eur J Endocrinol. 2006;155:609. doi: 10.1530/eje.1.02261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Ito N, Bartunek J, Spitzer KW, Lorell BH. Circulation. 1997;95:2303. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.95.9.2303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Vincent AM, TenBroeke M, Maiese K. Exp Neurol. 1999;155:79. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1998.6966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Vincent AM, TenBroeke M, Maiese K. J Neurobiol. 1999;40:171. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4695(199908)40:2<171::aid-neu4>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Kelley DE, He J, Menshikova EV, Ritov VB. Diabetes. 2002;51:2944. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.10.2944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Choo HJ, Kim JH, Kwon OB, Lee CS, Mun JY, Han SS, Yoon YS, Yoon G, Choi KM, Ko YG. Diabetologia. 2006;49:784. doi: 10.1007/s00125-006-0170-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Petersen KF, Befroy D, Dufour S, Dziura J, Ariyan C, Rothman DL, DiPietro L, Cline GW, Shulman GI. Science. 2003;300:1140. doi: 10.1126/science.1082889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Petersen KF, Dufour S, Befroy D, Garcia R, Shulman GI. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:664. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa031314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Douette P, Sluse FE. Free Radic Biol Med. 2006;40:1097. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2005.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Criscuolo F, Mozo J, Hurtaud C, Nubel T, Bouillaud F. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1757:1284. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2006.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Li B, Nolte LA, Ju JS, Han DH, Coleman T, Holloszy JO, Semenkovich CF. Nat Med. 2000;6:1115. doi: 10.1038/80450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Bernal-Mizrachi C, Weng S, Li B, Nolte LA, Feng C, Coleman T, Holloszy JO, Semenkovich CF. Arterioscler Thromb Vase Biol. 2002;22:961. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.0000019404.65403.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Kopecky J, Clarke G, Enerback S, Spiegelman B, Kozak LP. J Clin Invest. 1995;96:2914. doi: 10.1172/JCI118363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Zhang CY, Baffy G, Perret P, Krauss S, Peroni O, Grujic D, Hagen T, Vidal-Puig AJ, Boss O, Kim YB, Zheng XX, Wheeler MB, Shulman GI, Chan CB, Lowell BB. Cell. 2001;105:745. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00378-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Li LX, Skorpen F, Egeberg K, Jorgensen IH, Grill V. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;282:273. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.4577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Chan CB, De Leo D, Joseph JW, McQuaid TS, Ha XF, Xu F, Tsushima RG, Pennefather PS, Salapatek AM, Wheeler MB. Diabetes. 2001;50:1302. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.6.1302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Schrauwen P, Hesselink MK, Blaak EE, Borghouts LB, Schaart G, Saris WH, Keizer HA. Diabetes. 2001;50:2870. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.12.2870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.MacLellan JD, Gerrils MF, Gowing A, Smith PJ, Wheeler MB, Harper ME. Diabetes. 2005;54:2343. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.8.2343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Robertson LA, Kim AJ, Werstuck GH. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2006;84:39. doi: 10.1139/Y05-142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Hampton RY. Curr Biol. 2000;10:R518. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00583-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Ozcan U, Cao Q, Yilmaz E, Lee AH, Iwakoshi NN, Ozdelen E, Tuncman G, Gorgun C, Glimcher LH, Holamisligil GS. Science. 2004;306:457. doi: 10.1126/science.1103160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Nakatani Y, Kaneto H, Kawamori D, Yoshiuchi K, Hatazaki M, Matsuoka TA, Ozawa K, Ogawa S, Hori M, Yamasaki Y, Matsuhisa M. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:847. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411860200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Chong ZZ, Kang JQ, Maiese K. Histol Histopathol. 2003;18:173. doi: 10.14670/HH-18.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Lin SH, Maiese K. Neurosci Lett. 2001;298:207. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(00)01766-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Maiese K, Chong ZZ, Kang J. In: Neuronal and Vascular Plasticity: Elucidating Basic Cellular Mechanisms for Future Therapeutic Discovery. Maiese K, editor. Kluwer Academic Publishers; Norwell, MA: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 132.Chong ZZ, Kang J, Li F, Maiese K. Curr Neurovasc Res. 2005;2:197. doi: 10.2174/1567202054368317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Chong ZZ, Li F, Maiese K. Curr Neurovasc Res. 2006;3:107. doi: 10.2174/156720206776875830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Tomiyama M, Furusawa K, Kamijo M, Kimura T, Matsunaga M, Baba M. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2005;136:275. doi: 10.1016/j.molbrainres.2005.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Tong Q, Ouedraogo R, Kirchgessner AL. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2002;282:E1324. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00460.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Bialy L, Waldmann H. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2005;44:3814. doi: 10.1002/anie.200461517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Chong ZZ, Maiese K. Histol Histopathol. in press. [Google Scholar]

- 138.Andersen JN, Jansen PG, Echwald SM, Mortensen OH, Fukada T, Del Vecchio R, Tonks NK, Moller NP. FASEB J. 2004;18:8. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-1212rev. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Alonso A, Sasin J, Bottini N, Friedberg I, Osterman A, Godzik A, Hunter T, Dixon J, Mustelin T. Cell. 2004;117:699. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Stoker AW. J Endocrinol. 2005;185:19. doi: 10.1677/joe.1.06069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Nielo-Vazquez I, Fernandez-Veledo S, de Alvaro C, Rondinone CM, Valverde AM, Lorenzo M. Diabetes. 2007;56:404. doi: 10.2337/db06-0989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Ropelle ER, Pauli JR, Prada PO, de Souza CT, Faria MC, Picardi PK, Cintra DE, Fernandes MF, Flores MB, Velloso LA, Saad MJ, Carvalheira J. J Physiol. 2006;577:997. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.120006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Pagliarini DJ, Wiley SE, Kimple ME, Dixon JR, Kelly P, Worby CA, Casey PJ, Dixon JE. Mol Cell. 2005;19:197. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Ahmad F, Goldstein BJ. Am J Physiol. 1995;268:E932. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1995.268.5.E932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Chong ZZ, Maiese K. Histol Histopathol. 2004;19:495. doi: 10.14670/hh-19.495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Patapoutian A, Reichardt LF. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2000;10:392. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(00)00100-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Wodarz A, Nusse R. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1998;14:59. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.14.1.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Li F, Chong ZZ, Maiese K. Curr Neurovasc Res. 2005;2:331. doi: 10.2174/156720205774322557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Salinas PC. Biochem Soc Symp. 1999;65:101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Mao J, Wang J, Liu B, Pan W, Farr GH, 3rd, Flynn C, Yuan H, Takada S, Kimelman D, Li L, Wu D. Mol Cell. 2001;7:801. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00224-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Chen S, Guttridge DC, You Z, Zhang Z, Fribley A, Mayo MW, Kitajewski J, Wang CY. J Cell Biol. 2001;152:87. doi: 10.1083/jcb.152.1.87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.You Z, Saims D, Chen S, Zhang Z, Guttridge DC, Guan KL, MacDougald OA, Brown AM, Evan G, Kitajewski J, Wang CY. J Cell Biol. 2002;157:429. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200201110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Chong ZZ, Li F, Maiese K. Cell Signal. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2006.12.009. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Grant SF, Thorleifsson G, Reynisdottir I, Benediktsson R, Manolescu A, Sainz J, Helgason A, Stefansson H, Emilsson V, Helgadottir A, Styrkarsdottir U, Magnusson KP, Walters GB, Palsdottir E, Jonsdottir T, Gudmundsdottir T, Gylfason A, Saemundsdottir J, Wilensky RL, Reilly MP, Rader DJ, Bagger Y, Christiansen C, Gudnason V, Sigurdsson G, Thorsteinsdottir U, Gulcher JR, Kong A, Stefansson K. Nat Genet. 2006;38:320. doi: 10.1038/ng1732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Lehman DM, Hunt KJ, Leach RJ, Hamlington J, Arya R, Abboud HE, Duggirala R, Blangero J, Goring HH, Stern MP. Diabetes. 2007;56:389. doi: 10.2337/db06-0860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Scott LJ, Bonnycastle LL, Willer CJ, Sprau AG, Jackson AU, Narisu N, Duren WL, Chines PS, Stringham HM, Erdos MR, Valle TT, Tuomilehto J, Bergman RN, Mohlke KL, Collins FS, Boehnke M. Diabetes. 2006;55:2649. doi: 10.2337/db06-0341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Guo YF, Xiong DH, Shen H, Zhao LJ, Xiao P, Guo Y, Wang W, Yang TL, Recker RR, Deng HW. J Med Genet. 2006;43:798. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2006.041715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Wright WS, Longo KA, Dolinsky VW, Gerin I, Kang S, Bennett CN, Chiang SH, Prestwich TC, Gress C, Burant CF, Susulic VS, Macdougald OA. Diabetes. 2007;56:295. doi: 10.2337/db06-1339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159.Kanazawa A, Tsukada S, Sekine A, Tsunoda T, Takahashi A, Kashiwagi A, Tanaka Y, Babazono T, Matsuda M, Kaku K, Iwamoto Y, Kawamori R, Kikkawa R, Nakamura Y, Maeda S. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;75:832. doi: 10.1086/425340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160.Lin CL, Wang JY, Huang YT, Kuo YH, Surendran K, Wang FS. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17:2812. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005121355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 161.Balaraman Y, Limaye AR, Levey AI, Srinivasan S. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2006;63:1226. doi: 10.1007/s00018-005-5597-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 162.Nurmi A, Goldsteins G, Narvainen J, Pihlaja R, Ahtoniemi T, Grohn O, Koistinaho J. Free Radic Biol Med. 2006;40:1776. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2006.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 163.Qin W, Peng Y, Ksiezak-Reding H, Ho L, Stetka B, Lovati E, Pasinetti GM. Mol Psychiatry. 2006;11:172. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 164.Tanuma N, Sakuma H, Sasaki A, Matsumoto Y. Acta Neuropathol (Berl) 2006;112:195. doi: 10.1007/s00401-006-0083-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 165.Mussmann R, Geese M, Harder F, Kegel S, Andag U, Lomow A, Burk U, Onichtchouk D, Dohrmann C, Austen M. J Biol Chem. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609637200. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 166.Maiorana A, O’Driscoll G, Goodman C, Taylor R, Green D. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2002;56:115. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8227(01)00368-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 167.Howlett KF, Sakamoto K, Yu H, Goodyear LJ, Hargreaves M. Metabolism. 2006;55:1046. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2006.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 168.Tirosh A, Potashnik R, Bashan N, Rudich A. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:10595. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.15.10595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 169.Chong ZZ, Li F, Maiese K. Histol Histopathol. 2005;20:299. doi: 10.14670/hh-20.299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 170.Staal SP. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:5034. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.14.5034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 171.Staal SP, Huebner K, Croce CM, Parsa NZ, Testa JR. Genomics. 1988;2:96. doi: 10.1016/0888-7543(88)90114-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 172.Farese RV, Sajan MP, Standaert ML. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2005;230:593. doi: 10.1177/153537020523000901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 173.Kohn AD, Summers SA, Birnbaum MJ, Roth RA. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:31372. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.49.31372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 174.Carvalho E, Rondinone C, Smith U. Mol Cell Biochem. 2000;206:7. doi: 10.1023/a:1007009723616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 175.Krook A, Roth RA, Jiang XJ, Zierath JR, Wallberg-Henriksson H. Diabetes. 1998;47:1281. doi: 10.2337/diab.47.8.1281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 176.Bernal-Mizrachi E, Fatrai S, Johnson JD, Ohsugi M, Otani K, Han Z, Polonsky KS, Permutt MA. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:928. doi: 10.1172/JCI20016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 177.George S, Rochford JJ, Wolfrum C, Gray SL, Schinner S, Wilson JC, Soos MA, Murgatroyd PR, Williams RM, Acerini CL, Dunger DB, Barford D, Umpleby AM, Wareham NJ, Davies HA, Schafer AJ, Stoffel M, O’Rahilly S, Barroso I. Science. 2004;304:1325. doi: 10.1126/science.1096706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 178.Matsuzaki H, Tamatani M, Mitsuda N, Namikawa K, Kiyama H, Miyake S, Tohyama M. J Neurochem. 1999;73:2037. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 179.Rytomaa M, Lehmann K, Downward J. Oncogene. 2000;19:4461. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 180.Namikawa K, Honma M, Abe K, Takeda M, Mansur K, Obata T, Miwa A, Okado H, Kiyama H. J Neurosci. 2000;20:2875. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-08-02875.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 181.Chong ZZ, Kang JQ, Maiese K. Exp Cell Res. 2004;296:196. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2004.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 182.Henry MK, Lynch JT, Eapen AK, Quelle FW. Blood. 2001;98:834. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.3.834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 183.Kang JQ, Chong ZZ, Maiese K. J Neurosci Res. 2003;74:37. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 184.Suhara T, Mano T, Oliveira BE, Walsh K. Circ Res. 2001;89:13. doi: 10.1161/hh1301.092506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 185.Yamaguchi H, Wang HG. Oncogene. 2001;20:7779. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 186.Wick A, Wick W, Waltenberger J, Weller M, Dichgans J, Schulz JB. J Neurosci. 2002;22:6401. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-15-06401.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 187.Martin D, Salinas M, Lopez-Valdaliso R, Serrano E, Recuero M, Cuadrado A. J Neurochem. 2001;78:1000. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00472.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 188.Li F, Chong ZZ, Maiese K. Curr Neurovasc Res. 2006;3:187. doi: 10.2174/156720206778018758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 189.Okouchi M, Okayama N, Alexander JS, Aw TY. Curr Neurovasc Res. 2006;3:249. doi: 10.2174/156720206778792876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 190.Shah DI, Singh M. Mol Cell Biochem. 2007;295:65. doi: 10.1007/s11010-006-9273-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 191.Di Noia MA, Van Driesche S, Palmieri F, Yang LM, Quan S, Goodman AI, Abraham NG. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:15687. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M510595200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 192.Hyoda K, Hosoi T, Horie N, Okuma Y, Ozawa K, Nomura Y. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;340:286. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 193.Varma S, Lal BK, Zheng R, Breslin JW, Saito S, Pappas PJ, Hobson RW, 2nd, Duran WN. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;289:H1744. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01088.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 194.Maiese K, Li F, Chong ZZ. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2004;25:577. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2004.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 195.Maiese K, Li F, Chong ZZ. JAMA. 2005;293:90. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.1.90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 196.Dzietko M, Felderhoff-Mueser U, Sifringer M, Krutz B, Bittigau P, Thor F, Heumann R, Buhrer C, Ikonomidou C, Hansen HH. Neurobiol Dis. 2004;15:177. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2003.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 197.Parsa CJ, Matsumoto A, Kim J, Riel RU, Pascal LS, Walton GB, Thompson RB, Petrofski JA, Annex BH, Stamler JS, Koch WJ. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:999. doi: 10.1172/JCI18200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 198.Chong ZZ, Lin SH, Kang JQ, Maiese K. J Neurosci Res. 2003;71:659. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 199.Mojiminiyi OA, Abdella NA, Zaki MY, El Gebely SA, Mohamedi HM, Aldhahi WA. Diabet Med. 2006;23:839. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2006.01893.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 200.Symeonidis A, Kouraklis-Symeonidis A, Psiroyiannis A, Leotsinidis M, Kyriazopoulou V, Vassilakos P, Vagenakis A, Zoumbos N. Ann Hematol. 2006;85:79. doi: 10.1007/s00277-005-1102-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 201.Thomas MC, Cooper ME, Tsalamandris C, MacIsaac R, Jerums G. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:466. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.4.466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 202.Silverberg DS, Wexler D, Blum M, Tchebiner JZ, Sheps D, Keren G, Schwartz D, Baruch R, Yachnin T, Shaked M, Schwartz I, Steinbruch S, Iaina A. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2003;18:141. doi: 10.1093/ndt/18.1.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 203.van der Meer P, Voors AA, Lipsic E, Smilde TD, van Gilst WH, van Veldhuisen DJ. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44:63. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.03.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 204.Henry DH, Bowers P, Romano MT, Provenzano R. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:262. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.3.262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 205.Maiese K, Li F, Chong ZZ. JAMA. 2005;293:1858. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.1.90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]