Abstract

In both humans and mice, treatment with TNF-α antagonists is associated with serious infectious complications including disseminated histoplasmosis. The mechanisms by which inhibition of endogenous TNF-α alter protective immunity remain obscure. Herein, we tested the possibility that neutralization of this cytokine triggered the emergence of T cells that dampen immunity. The lungs of mice given mAb to TNF-α contained a higher proportion and number of CD4+CD25+ cells than controls. This elevation was not observed in IFN-γ- or GM-CSF-deficient mice or in those given a high inoculum. Phenotypic analysis revealed that these cells lacked many of the characteristics of natural regulatory T cells, including Foxp3. CD4+CD25+ cells from TNF-α-neutralized mice suppressed Ag-specific, but not nonspecific, responses in vitro. Elimination of CD25+ cells in vivo restored protective immunity in mice given mAb to TNF-α and adoptive transfer of CD4+CD25+ cells inhibited immunity. In vitro and in vivo, the suppressive effect was reversed by mAb to IL-10. Thus, neutralization of TNF-α is associated with the induction of a population of regulatory T cells that alter protective immunity in an Ag-specific manner to Histoplasma capsulatum.

The dimorphic fungus, Histoplasma capsulatum, is soilbased and is found world-wide. In the US, it is endemic to the southeastern and midwestern sections of the country. Infection is acquired when soil containing fungal elements is disrupted and particles inhaled. Subsequently, the organism converts to the pathogenic yeast phase in lungs, disseminates to organs rich in mononuclear phagocytes, and replicates intracellularly until cellular immunity halts its growth (1). The fungus establishes a persistent state, presumably within granulomas, that are present in multiple tissues. These niches serve as potential sites for reactivation of fungal growth once immunity has become impaired sufficiently (1, 2).

Host resistance to this fungus is dependent on the coordinated action of several cell populations and cytokines. T cells and phagocytes (dendritic cells and Mϕ) must cooperate to achieve successful resolution of infection (3-5). The endogenous cytokines that are necessary for preventing overwhelming infection include IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-1, and GM-CSF (6-12). Moreover, perforin and leukotrienes also are key regulators of protective immunity (13-15).

Several factors have been associated with disseminated histoplasmosis; they include principally immunosuppressive pharmaceuticals and AIDS. Among the most recent pharmacological agents implicated in this form of infection are the TNF-α antagonists (16-18). Compelling data indicate that these agents definitively augment the risk of disseminated histoplasmosis. The only human study to suggest a mechanism has been performed in vitro and has reported that infliximab, a chimeric mAb to TNF-α, depresses IFN-γ production by lymphocytes incubated with Histoplasma capsulatum-infected alveolar macrophages (19).

The effect of TNF-α antagonists on human disease was preceded by observations in mice in which neutralization of endogenous TNF-α leads to overwhelming infection in naive and immune mice (6, 10, 11). In the former, the increased susceptibility to infection is associated with depressed levels of NO, an essential mediator of host resistance to this pathogen. In secondary histoplasmosis, neutralization of TNF-α leads to elevations in IL-4 and IL-10, which dampen immunity sufficiently such that mice cannot combat the fungus (6). Subsequent studies in mice have demonstrated that neutralization of TNF-α irreversibly impairs the generation of protective T cells in vivo (20).

Accumulating evidence in mice and humans indicates that TNF-α regulates the emergence of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells (Tregs)3 (21). Young NOD mice, administered mAb to TNF-α, manifested increased numbers and function of these cells (22). Rheumatoid arthritis patients receiving inflixmab exhibit increased numbers of Treg in their circulation (23). These reports raise the possibility that one potential mechanism by which antagonism of endogenous TNF-α increases susceptibility to infection with H. capsulatum is by the generation of T cells that would dampen cellular immunity. Natural Tregs are known to impair immunity to several intracellular pathogens including Leishmania major and Mycobacterium tuberculosis (24, 25) Herein, we postulated that neutralization of TNF-α may provide the proper milieu for the emergence of a population of CD4+CD25+ cells that inhibit protective immunity. We found a population of Ag-specific CD4+CD25+ T cells that inhibited cellular immunity both in vivo and in vitro. These cells lacked the common phenotypic characteristics of natural Tregs and, in fact, resembled an activated population.

Materials and Methods

Mice

C57BL/6 and TCR αβ-/- mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory. Animals were housed in isolator cages and were maintained by Department of Laboratory Animal Medicine, University of Cincinnati, which is accredited by the American Association for Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Medicine. All animal experiments were done in accordance with the Animal Welfare Act guidelines of the National Institutes of Health.

Preparation of H. capsulatum and infection

H. capsulatum yeast (strain G217B) was prepared as described previously (6). To produce infection in naive mice, animals were infected intranasally (i.n.) with 2 × 106 H. capsulatum yeasts in a 30-μl vol of HBSS. For secondary histoplasmosis, mice were initially inoculated with 104 yeast i.n. in a volume of 30 μl. Six to 8 wk later, previously exposed animals were rechallenged i.n. with 2 × 106 yeasts.

Organ culture

Recovery of H. capsulatum was performed as described elsewhere (6). Fungal burden was expressed as mean CFU per whole organ ± SEM. The limit of detection is 102 CFU.

mAb and reagents

Rat anti-mouse TNF-α (from cell line XT-22.1) and rat anti-mouse CD25 (from cell line PC 61.) was produced and purified at the National Cell Culture Center (Minneapolis, MN). The cell line for mAb to TNF-α was obtained from Dr. J. Abrams (DNAX, Palo Alto, CA). mAb to mouse IL-4, IL-9, IL-10, and CD3 were purchased from BD Biosciences. mAb to mouse TGF-β was provided by Drs. Marcel Wüthrich and Bruce Klein. Mouse IgG, Rat IgG, and Hamster IgG were purchased from Pierce. Methyl-l-tryptophan was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. It was used at a final concentration of 0.5 mM.

Preparation of lung leukocytes

Lungs were teased apart with the frosted ends of two glass slides in 10 ml of HBSS. The solution was filtered through 60-μm nylon mesh (Spectrum Laboratories) and washed three times with HBSS. Leukocytes were isolated by separation using Lympholyte-M (Cedarlane Laboratories).

Flow cytometry

To determine the percentage of putative Treg, lung leukocytes and splenocytes were adjusted to a concentration of 2 × 106 cells/200 μl of staining buffer (consisting of PBS (pH 7.4)), 2% BSA, and 0.02% sodium azide (PBSA) and were incubated with 0.5 μg of mAb (BD Biosciences) to FITC-labeled CD3ε (clone 145-2C11), PerCP-labeled CD4 (clone RM4-5), allophyocyanin-labeled CD25 (clone PC61.5), and R-PE-labeled mAb to one of the following: CD69 (clone H1.2F3), CD152 (clone UC10-4F10-11), CD223 (clone C9B7W), CD103 (clone M290), or glucocorticoid inducible TNFR (GITR; TNFRSF18, clone DTA (eBioscience)). To assess depletion of CD25+ cells, allophyocyanin-labeled CD25 from a different clone (3C7; BD Biosciences) was used. To determine the expression of intracellular Foxp3, surface-stained cells were washed in staining buffer, fixed, and permeabilized in 1 ml of fixation/permeabilization working solution, washed several times in permeabilization buffer, and stained with R-PE-conjugated mAb (eBioscience) to Foxp3 (clone FJK-16s.1; 2.5 μg/1 × 106 cells). The cells were fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde.

Intracellular IL-10 staining on lung leukocytes was performed as described (26). Cells were stained with mAb to CD3, CD4, and CD25 followed by permeabilization of cells and incubation with PE-conjugated mAb to IL-10 (BD Biosciences).

Isolation of T cells

To obtain T cells, lung leukocytes were pooled from mice receiving IgG or mAb to TNF-α at day 7 of infection. Cells were adjusted to 2 × 107/ml, layered over 2-5 ml of Lympholyte-M (Cedarlane Laboratories), and centrifuged at 1500 xg for 20 min. Cells were washed in PBS supplemented with 0.5% BSA and 2 mM EDTA. Cells were adjusted to 1 × 107/90 μl in PBS. Four hundred μl of CD90 microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec) were added to cells for a final concentration of 10 μl/107 cells. After a 15 min incubation at 6-12°C, cells were washed and resuspended in PBS. Cells were percolated through MACS columns (Miltenyi Biotec). The column was washed three times with PBS, removed from the magnetic field, and flushed with PBS. The positive fraction was washed twice with HBSS. The purity of CD3+ cells exceeded 95% by flow cytometry.

For CD4+CD25+ cells, lung leukocytes were pooled from 8-12 mice and the concentration adjusted to 107 cells/40 μl of buffer, consisting of PBS (pH 7.2) supplemented with 0.5% BSA and 2 mM EDTA, and labeled with 10 μl/107 cells of a mixture of biotin-conjugated mAb to: CD8α (Ly-2), CD11b (Mac-1), CD45R (B220), CD49b (DX5), and Ter-119, followed by addition of 20 μl anti-biotin MACS microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec) and 10 μl of mAb to CD25 conjugated to R-PE. CD8+CD25+ cells were isolated in a similar fashion with the exception that biotin-conjugated mAb to CD4 was used rather than CD8α. The cells were washed in MACS buffer and loaded onto a MACS LD column, which was placed in the magnetic field of a MACS separator. The unlabeled CD4+ cells ran through the column and were collected. The CD25-PE labeled cells were magnetically labeled with 10 μl of anti-PE microbeads and applied to a MACS MS column in a magnetic field. The labeled cells were retained in the column, which was then removed from the magnetic field, and the cells were eluted onto another MS column. Similarly, the retained cells were again eluted and enumerated. Purity of these cells exceeded 95% as determined by flow cytometry.

T cell line

A T cell line, named RGCW/M, that was reactive to an Ag extract from the cell wall and cell membrane of H. capsulatum was generated and maintained as previously described (27, 28).

Proliferation assay

T cell proliferation for the T cell line was assessed by [3H]thymidine incorporation, as reported (27). To assay nonspecific proliferation, wells of a 96-well plate were coated with mAb to CD3 at a concentration of 10 μg/ml for 90 min at 37°C in 5% CO2. Subsequently, wells were washed thoroughly with PBS. A total of 105 T cells in 100 μl of RPMI 1640 containing 10% FBS and 10 μg/ml gentamicin were incubated with 5 × 105 irradiated splenocytes in 100 μl of medium and decreasing numbers of CD4+CD25+ cells (in 50 μl) from H. capsulatum-infected mice given rat IgG or mAb to TNF-α. In studies of mAb neutralization in vitro, a final concentration of 1 μg/ml was used.

In vivo treatment with mAb

Mice were injected i.p. with 1 mg of mAb to TNF-α, mAb to CD25, or an equivalent amount of rat IgG at the time of challenge with H. capsulatum and each week thereafter. One mg of mAb to TNF-α inhibits the biological activity of TNF-α for up to 7 days (6). Treatment with mAb to CD25 caused a greater than 99% reduction in CD25+ cells from H. capsulatum-infected mice as assessed by flow cytometry using allophycocyanin-conjugated CD25 from clone 3C7, which recognizes a different epitope than PC61.5 (29). In other experiments, mice were injected with 1 mg of mAb to IFN-γ (XMG 1.2) at the time of infection.

Cell transfer

TCR αβ-/- mice were injected i.p. with 2 × 105 T cells from mice that had recovered from i.n. infection with H. capsulatum. Four days later, mice were injected with 2 × 105 CD4+CD25+ cells from mice infected for 1 wk and administered rat IgG or mAb to TNF-α.

Statistics

ANOVA was used to compare groups. p < 0.05 was defined as significant. Survival was analyzed by log rank test.

Results

CD4+CD25+ cells are proportionally and numerically increased in mice given mAb to TNF-α

C57BL/6 mice were infected with 2 × 106 H. capsulatum yeasts and given PBS, rat IgG, or mAb to TNF-α on the day of primary and secondary infection. Lung leukocytes and splenocytes were stained for CD3, CD4, and CD25. We selected day 7 because mice lacking TNF-α are ill but not moribund at this time. We gated on CD3+ cells and determined the proportion of CD4+CD25- and CD4+CD25+ cells. The data were expressed as a ratio of CD4+CD25+ cells divided by total CD4+ cells and as the absolute number of cells. We examined the ratio of CD4+CD25+ cells to total CD4+ T cells because this value may be more important than absolute values in the assessment of disease caused by infection (30).

In both primary and secondary histoplasmosis, the proportion and number of CD4+CD25+ cells in lungs of mice given mAb to TNF-α were significantly higher (from p < 0.05 to p < 0.01) than that found in infected controls (Table I). These values were not increased in the spleens of mAb to TNF-α recipients compared with infected controls (Table I). In secondary infection, CD4+CD25+ cells were increased in both lungs and spleens.

Table I.

CD4+CD25+ T cells are increased in lungs of mice infected with H. capsulatum for 7 days and given mAb to TNF-αa

| Organ | Infection | Treatment or Deficiency | Mean (±SEM) CD4+CD25+/CD4+ Ratio | Mean (±SEM) No. of CD4+CD25+ Cells × 104 | Mean log10 CFU ± SEM at Day 7 of Infection |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lung | Primary | PBS | 0.39 ± 0.2 | 6.9 ± 0.7 | 6.1 ± 0.4 |

| rat IgG | 0.42 ± 0.4 | 7.3 ± 0.8 | 6.2 ± 0.3 | ||

| anti-TNF-α | 0.63 ± 0.1b | 17.2 ± 0.1b | 7.6 ± 0.5c | ||

| IFN-γ-/- | 0.37 ± 0.2 | 4.3. ± 1.0 | 7.8 ± 0.2c | ||

| GM-CSF-/- | 0.43 ± 0.6 | 3.4 ± 0.9 | 7.7 ± 0.6c | ||

| Secondary | PBS | 0.17 ± 0.14 | 97.2 ± 11.9 | 5.6 ± 0.6 | |

| rat IgG | 0.15 ± 0.20 | 95.4 ± 12.1 | 5.8 ± 0.4 | ||

| anti-TNF-α | 0.53 ± 0.11c | 240.0 ± 10.1c | 7.3 ± 0.3c | ||

| Spleen | Primary | PBS | 0.15 ± 0.05 | 197.1 ± 15.6 | 4.8 ± 0.4 |

| rat IgG | 0.18 ± 0.08 | 211.2 ± 14.1 | 5.0 ± 0.2 | ||

| anti-TNF-α | 0.16 ± 0.02 | 218.5 ± 8.3 | 6.6 ± 0.4c | ||

| Secondary | PBS | 0.17 ± 0.04 | 189.9 ± 15.6 | 3.1 ± 0.8 | |

| rat IgG | 0.18 ± 0.02 | 195.6 ± 18.3 | 3.2 ± 0.2 | ||

| anti-TNF-α | 0.28 ± 0.02d | 379.2 ± 38.3c | 3.8 ± 0.3 |

n = 8-10 per group. All studies were performed at least twice and represent data from two independent studies.

p < 0.05 cf to rat IgG and PBS.

p < 0.01 cf to rat IgG and PBS.

p = 0.02 cf to rat IgG and PBS.

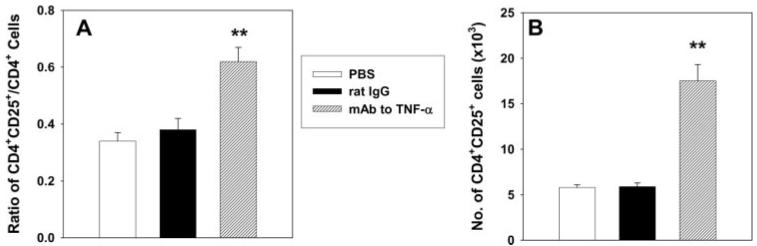

We asked whether the increase in CD4+CD25+ cells was apparent before day 7 of infection. H. capsulatum-infected mice were administered PBS, rat IgG, or mAb to TNF-α. Animals were sacrificed on day 4, and the lungs were assessed for the presence of CD4+CD25+ cells. The proportion and number of these cells in TNF-α-neutralized mice was markedly higher (p < 0.01) than that of infected controls (Fig. 1).

FIGURE 1.

The proportion and numbers of CD4+CD25+ cells in TNF-α-neutralized mice are increased as early as day 4. Mice were infected with H. capsulatum and treated with rat IgG or mAb to TNF-α at the time of infection. Data represent mean ± SEM (n = 6-8) of Ratio (A) of CD4+CD25+/CD4+ cells and numbers (B). **, p < 0.01. Studies represent pooled data from two experiments.

We sought to determine whether the effect of TNF-α on CD4+CD25+ cells was dependent on the presence of infection. Naive uninfected mice were given rat IgG or mAb to TNF-α, and the proportion of CD4+CD25+ cells was assessed in spleens 7 days later. We limited our studies to this organ because the number of mice needed to obtain sufficient numbers of cells from lungs is large. The proportion of CD4+CD25+cells/CD4+CD25- cells in naive controls was 0.35 ± 0.24 (n = 4), and in those given mAb to TNF-α, it was 0.31 ± 0.3 (n = 4). The proportion of Foxp3+CD4+CD25+ cells in controls (13.6 ± 0.7%, n = 5) did not differ (p > 0.05) from that of TNF-α-neutralized mice (14.9 ± 1.2%).

Is the increase in CD4+CD25+ cells observed in mice deficient in IFN-γ or GM-CSF?

To determine whether the increase in CD4+CD25+ cells was specific for a deficiency of TNF-α, we examined other Histoplasma-susceptible, cytokine-deficient mice. We infected IFN-γ-/- or GM-CSF-/- mice with 2 × 106 yeasts, and at day 7 of infection, analyzed the proportion and number of CD4+CD25+ cells and fungal burden. The lungs of mice lacking IFN-γ or GM-CSF did not exhibit an altered ratio or an increased number of CD4+CD25+ cells, although recovery of H. capsulatum in lungs of mutant mice was similar to that of TNF-α-neutralized mice (Table I) (31).

Do the proportion and number of CD4+CD25+ depend on the fungal burden in immunocompetent mice?

One of the obvious differences in mice receiving mAb to TNF-α, as compared with infected controls, is the fungal burden. Although IFN-γ- or GM-CSF-deficient mice exhibited an increased fungal burden, the deficiency in cytokine may blur interpretation of the actual influence of burden. To determine whether the increase in CD4+CD25+ cells could be attributed to an elevated fungal burden in otherwise normal mice, we infected the latter with 2 × 106 yeasts and treated them with rat IgG or mAb to TNF-α. The third group received an inoculum of 107 yeasts. At day 7, the number of CD4+CD25+ cells in mice receiving the high inoculum was similar to those who were infected with 2 × 106 yeasts and less than that of TNF-α-neutralized, infected mice (Fig. 2A). Although the number of CD4+CD25+ cells in recipients of a high dose was similar to the lower dose, the number of yeasts recovered at day 7 was similar to that of mice receiving mAb to TNF-α (Fig. 2B).

FIGURE 2.

The proportion and number of CD4+CD25+ cells depends on neutralization of TNF-α and not fungal burden. Groups of mice (n = 6-8) were infected with 2 × 106 yeasts i.n. and given rat IgG or mAb to TNF-α. Another group received 107 yeasts i.n. The mean (±SEM) number (A) of CD4+CD25+ cells at day 7 of infection is illustrated. Results represent data from two pooled experiments. In B is the mean number of CFU (±SEM) of each group (n = 5-6). **, p < 0.01.

CD25 is not increased on CD8+ cells

To determine whether increases in CD25+ cells were limited to the CD4+ population, we infected mice and analyzed the proportion and number of CD8+CD25+ cells. In primary and secondary infection, the number of this cell population in lungs or spleens of mice given PBS or control Ab did not differ from that in animals given mAb to TNF-α (Table II). Thus, the increase in CD25 was restricted to the CD4+ population.

Table II.

CD8+CD25+ cells in lungs of mice infected for 7 days and given mAb to TNF-αa

| Infection | Treatment | Mean (±SEM) CD8+CD25+/CD8+ Ratio | Mean (±SEM) No. of CD8+CD25+ Cells × 104 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lung | Primary | PBS | 0.59 ± 0.10 | 4.0 ± 0.3 |

| rat IgG | 0.63 ± 0.15 | 4.2 ± 0.5 | ||

| anti-TNF-α | 0.51 ± 0.10 | 4.6 ± 0.8 | ||

| Secondary | PBS | 0.36 ± 0.04 | 6.6 ± 0.4 | |

| rat IgG | 0.34 ± 0.08 | 6.4 ± 0.3 | ||

| anti-TNF-α | 0.29 ± 0.04 | 5.6 ± 0.2 | ||

| Spleen | Primary | PBS | 0.07 ± 0.02 | 118.6 ± 10.4 |

| rat IgG | 0.05 ± 0.01 | 113.9 ± 8.3 | ||

| anti-TNF-α | 0.04 ± 0.01 | 102.3 ± 11.6 | ||

| Secondary | PBS | 0.12 ± 0.02 | 183.3 ± 14.5 | |

| rat IgG | 0.10 ± 0.01 | 178.6 ± 17.3 | ||

| anti-TNF-α | 0.12 ± 0.01 | 187.1 ± 18.9 |

Mean ± SEM of 6-8 mice.

Phenotypic analysis of CD4+CD25+ cells in mice given mAb to TNF-α

One of the hallmarks of naturally occurring Treg is the expression of the transcription factor Foxp3 (32). We examined its presence in CD4+CD25+ cells on day 7 of infection by intracellular staining. Foxp3 expression by lung CD4+CD25+ cells from TNF-α-neutralized mice was minimal and did not differ from that of infected controls in either primary or secondary infection (Table III). Concomitantly, we examined LAG3 (CD223), GITR, CD86, CD103, and CD152 expression on lung CD4+CD25+ cells from mice infected with H. capsulatum for 7 days (Table III). In primary infection, expression of CD86, GITR, CD152, and CD223 by CD4+CD25+ cells did not differ between infected controls and TNF-α-neutralized mice. In secondary histoplasmosis, LAG3 (CD223)-bearing CD4+CD25+ cells from mice given mAb to TNF-α exceeded by 10-fold (p < 0.01) those from infected controls. CD86, in contrast, was far higher in controls than in TNF-α-neutralized mice.

Table III.

Quantitative analysis of phenotype of CD4+CD25+ cellsa

| Mean Percentage (±SEM) of CD4+CD25+ Cells Treatment of Miceb |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Infection | mAb to | Rat IgG | mAb to TNF-α |

| Primary | Foxp3 | 44.4 ± 3.5 | 33.3 ± 0.8 |

| CD86 | 41.8 ± 3.8 | 42.1 ± 1.4 | |

| CD152 | 50.9 ± 1.0 | 36.7 ± 5.6 | |

| GITR | >99 | >99 | |

| CD223 | 8.4 ± 0.3 | 8.3 ± 0.6 | |

| CD103 | 49.1 ± 2.8 | 17.3 ± 0.2c | |

| Secondary | Foxp3 | <1 | <1 |

| CD86 | 35.0 ± 3.0 | 2.3 ± 0.9c | |

| CD152 | 0.9 ± 0.4 | 0.8 ± 0.3 | |

| GITR | 45.8 ± 4.6 | 2.6 ± 1.1c | |

| CD223 | 2.3 ± 0.4 | 23.5 ± 3.2c | |

| CD103 | 40.3 ± 4.2 | 11.4 ± 1.6c | |

Staining for Foxp3 was intracellular, whereas the others markers were surface stained.

Mean % ±SEM (n = 6-8) performed in two separate experiments.

p < 0.01.

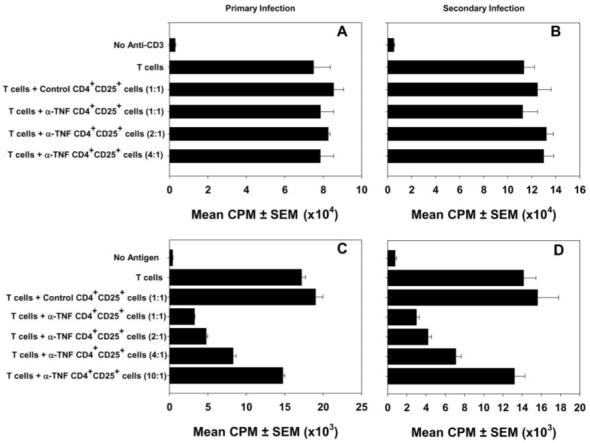

CD4+CD25+, but not CD8+CD25+, cells from mice given mAb to TNF-α suppress proliferative responses in vitro in an Ag-dependent manner

CD25 is an activation marker for T cells in addition to denoting Treg. The principal means by which activated T cells are distinguished from Treg is functionally, in that the latter can suppress immune responses in vitro. We isolated CD4+CD25+ cells from H. capsulatum-infected mice given rat IgG or mAb to TNF-α and tested their ability to suppress nonspecific T cell responses to anti-CD3. CD4+CD25+ cells from either group failed to inhibit proliferation of normal T cells in response to anti-CD3 (Fig. 3, A and B). CD4+CD25+ cells dampened the proliferative response by the Histoplasma-specific T cell line RGCWM to the antigenic extract from the cell wall and cell membrane of the fungus (Fig. 3, C and D).

FIGURE 3.

CD4+CD25+ cells from H. capsulatum-infected mice suppress proliferation of T cells in an Ag-specific manner. Lung CD4+CD25+ cells from mice with primary infection (A and C) or secondary infection (B and D) were incubated with a T cell line stimulated with either anti-CD3 (A and B) or cell wall and cell membrane (C and D). Cells were collected on day 7 of infection. [3H]thymidine incorporation was assessed after 3 days. Data represent mean ± SEM of triplicate wells. One experiment of six is shown.

In a separate set of experiments, we isolated CD8+CD25+ cells from infected mice given rat IgG or mAb to TNF-α. Neither population dampened the proliferative response by the T cell line. The mean cpm response (±SEM) by T cells to Ag in the absence of additional cells was 52,072 ± 4,492 (unstimulated cells = 4,411 ± 338). When T cells were incubated with an equal number of CD8+CD25+ cells from infected mice given rat IgG, the response was 45,578 ± 1,678 (unstimulated cells = 3,575 ± 152). This number was similar to that of T cells incubated with CD8+CD25+ cells from the lungs of infected mice given mAb to TNF-α. That value was 49,456 ± 2,592 (unstimulated cells = 4,056 ± 651).

The in vitro suppressive effect is dependent on the expression of IL-10

Several cytokines have been implicated in the suppressive effect of putative Treg including IL-10, TGF-β, and IL-9 (33-35). Therefore, we incubated mAb to IL-9, IL-10, and TGF-β with cocultures of the T cell line RGCWM plus CD4+CD25+ cells from the lungs of infected mice treated with mAb to TNF-α. In addition, we examined the influence of an inhibitor of IDO. This enzyme has been implicated in the effector function of Tregs (36). Treatment of cocultures with mAb to IL-10 reversed the suppressive effect of CD4+CD25+ cells from lungs of mice given mAb to TNF-α (Fig. 4A). In secondary histoplasmosis, neutralization of TNF-α is associated with elevated levels of IL-4 and IL-10 in lung homogenates (6). We, therefore, added mAb to IL-4 to our analysis. The functional properties of CD4+CD25+ cells from mice with secondary infection and given mAb to TNF-α was reversed only by IL-10 neutralization (Fig. 4B).

FIGURE 4.

Suppression is dependent on IL-10. The data depict the modulation of suppression by CD4+CD25+ cells from mice with primary (A) and secondary (B) infection incubated with 1000 pg of mAb to IL-9, IL-10, and TGF-β. In secondary, 1000 pg of mAb to IL-4 also is used. One experiment of three is shown.

Elimination of CD25+ cells is curative in TNF-α-neutralized mice

Because CD4+CD25+ cells were elevated in TNF-α-neutralized mice, we sought to determine whether these cells contributed to the demise of the animals given mAb to TNF-α. Groups of mice (n = 6-8) were infected with 2 × 106 yeasts and given control Ab, control Ab plus mAb to CD25, control Ab plus mAb to TNF-α, or mAb to TNF-α plus CD25. Mice received anti-CD25 and/or anti-TNF-α or an equal amount of rat IgG. The burden in lungs and spleens at day 7 was significantly higher (p < 0.01) in mice given mAb to TNF-α as compared with infected controls or those given mAb to CD25. In mice given both mAb, the fungal burden was similar to recipients of control Ab or mAb to CD25 (Fig. 5, A and B). In a survival study, all mice given mAb to TNF-α died, whereas 100% of the infected controls, those given mAb to CD25 or given mAb to CD25 and TNF-α, survived (Fig. 5C).

FIGURE 5.

Elimination of CD25+ cells ameliorates the detrimental effects of mAb to TNF-α. Mice were infected with 2 × 106 yeasts and treated with mAb to CD25, mAb to TNF-α, or both and fungal burden assessed in lungs (A) and spleens (B) at day 7. Data represent mean log10 CFU ± SEM of 6-8 animals. **, p < 0.01. In C is a survival curve with n = 6. One of two experiments is shown.

We determined whether elimination of CD25+ cells would rescue infected mice given mAb to IFN-γ or wild-type animals given a high inoculum. IFN-γ-neutralized mice were infected with 2 × 106 yeasts i.n. and given either rat IgG or mAb to CD25. The mean survival time (±SEM) of the mutant mice given rat IgG (12.1 ± 2.3 days) was similar to that of mice given mAb to CD25 (11.9 ± 1.5 days). Likewise, the survival of mice infected with 107 yeasts and given rat IgG (14.8 ± 2.4 days) did not differ (p > 0.05) from that of mice given mAb to CD25 (15.3 ± 1.9 days). All mice given mAb to TNF-α and CD25 survived for 45 days.

Identical experiments were performed in secondary histoplasmosis. The fungal burden in mice treated with rat IgG plus mAb to CD25 did not differ from that of controls. TNF-α neutralization caused a marked increase in CFU (p < 0.001) compared with infected controls and mAb CD25 recipients (Fig. 6). Elimination of CD25+ cells sharply reduced fungal burden in TNF-α-neutralized mice (p < 0.01), but it did not reduce the burden to the level of controls or mice given mAb to CD25 (Fig. 6). Treatment with mAb did improve survival of TNF-α-neutralized mice but was not as effective as seen in primary infection (Fig. 6).

FIGURE 6.

Elimination of CD25+ cells ameliorates the inimical effects of mAb to TNF-α in secondary histoplasmosis. Immune mice were infected as above and treated identically. Fungal burden in lungs (A) and spleens (B) is illustrated. The data are mean log10 CFU ± SEM. C shows a survival curve. One of two experiments is shown.

Transfer of CD4+CD25+ cells from mice given mAb to TNF-α modulates protective immunity in vivo

Groups of TCR αβ-/- mice were injected with 2 × 105 T cells from the lungs of mice infected for 7 days. After 5 days, mice were injected with an equal number of CD4+CD25+ from the lungs of TNF-α-neutralized mice or from infected controls. One day later, mice were infected with 2 × 106 yeasts and observed for survival. Infected TCR αβ-/- mice that did not receive any cells died by day 15. Transfer of T cells from lungs of mice prolonged survival of TCR αβ-/- mice (Fig. 7). Cotransfer of T cells plus CD4+CD25+ cells from infected controls also increased survival, as compared with mice that received no cells. In contrast, the injection of CD4+CD25+ cells from mice given mAb to TNF-α blunted immunity because all these mice died within 16 days. Administration of mAb to IL-10 reversed the detrimental effects of these cells but had no effect on the CD4+CD25+ cells from infected controls (Fig. 7).

FIGURE 7.

Adoptive transfer of CD4+CD25+ lung cells from mice given mAb to TNF-α blunts protective immunity. TCR αβ-/- mice were injected i.p. with 2 × 105 T cells from the lungs of mice infected for 7 days with H. capsulatum. Five days later, mice received 2 × 105 CD4+CD25+ cells from the lungs of mice given rat IgG or mAb to TNF-α. A separate group received no cells and another group received only T cells. One day later, mice were infected with 2 × 106 yeasts. Mice (n = 5) were followed for survival.

Synthesis of IL-10 by CD4+CD25+ cells

Because IL-10 mediated the immunodepression associated with CD4+CD25+ cells from TNF-α-neutralized animals, we determined the frequency of IL-10 producing cells in infected mice. Mice were infected with 2 × 106 yeasts i.n. and given either rat IgG or mAb to TNF-α. At day 7 of infection, we analyzed CD4+CD25+ cells for intracellular IL-10. The mean percentage (±SEM) of IL-10+CD4+CD25+ cells from infected controls (1.8 ± 0.2%, n = 5) was diminished (p < 0.05) as compared with those cells from TNF-α-neutralized mice (4.3 ± 0.3%, n = 5). A representative flow cytometric profile is illustrated in Fig. 8.

FIGURE 8.

Intracellular IL-10 synthesis by CD4+CD25+ lung cells from Histoplasma-infected mice. Flow diagram of IL-10+ cells. Lung leukocytes of mice infected with H. capsulatum for 7 days were stained intracellularly for IL-10 and surface stained with mAb toCD3, CD4, and CD25. The cells were gated on the CD3+CD4+ population and analyzed. A represents cells from an infected control and B represents cells from a mouse given mAb to TNF-α. A total of 105 events were analyzed.

Discussion

The introduction of TNF-α antagonists into the clinical arena has been exceptionally useful in the treatment of several chronic inflammatory conditions including rheumatoid arthritis, Crohn’s disease, or psoriatic arthritis (37-39). Although these therapies have ameliorated the severity of illness, they have had untoward consequences. Among the adverse events is an increased incidence of infections with intracellular pathogens, including H. capsulatum (40). In ongoing work, we have been interested in the mechanisms by which inhibition of this cytokine modulates protective immunity. Multiple defects have been uncovered, including an impairment in the protective function of T cells upon adoptive transfer (20). In this manuscript, we demonstrate that one explanation for the failure of T cells to exert protection in conjunction with TNF-α neutralization is the induction of a population of Ag-specific CD4+CD25+ cells.

Several pieces of evidence indicate that the regulatory cell population was in the CD4+CD25+ population. These cells were increased in proportion and number in the lungs of H. capsulatum-infected mice given mAb to TNF-α. In vitro suppressive activity was exerted by CD4+CD25+ cells from TNF-α-neutralized mice, and adoptive transfer of this purified population suppressed the protective function of T cells from immune animals.

Two populations of Treg have been defined, but the boundaries that distinguish each are imprecise. One population is termed naturally occurring, and the other is induced or adaptive. Natural Treg arise in the thymus and migrate into the periphery. Expansion of this population is dependent on IL-2 (41). Naturally occurring Treg express CD25, CD152 (CTLA-4, a molecule that inhibits cellular responses), and GITR. Other molecules that naturally occurring Treg express include CD103 (αE integrin), CD134 (OX-40), and/or CD223 (Lag 3) (42). The transcription factor, Foxp3, is required for generation of naturally occurring Treg, and its transcription is enhanced in these cells (43). In contrast, induced Treg originate in the periphery and variably express these markers, including Foxp3 and CD25. This finding suggests that adaptive Treg are a highly heterogeneous population largely defined by function rather than surface markers. This population is postulated to respond to microbial Ags that remain largely uncharacterized (32, 44-47). The CD4+CD25+ population in TNF-α-neutralized mice did not exhibit the phenotypic characteristics of natural Treg nor did they exert the functional property of these cells because they did not depress immune responses nonspecifically. Interestingly, the CD4+CD25+ population coexpressed the T cell activation marker CD69, thus suggesting that it exhibits an effector phenotype. The phenotype of immunoregulatory T cells in mice given mAb to TNF-α differs from the recently described effector CD4+CD25- T cells that synthesize IL-10 and IFN-γ (48, 49).

Distinguishing effector T cells from the population of regulatory T cells described herein is complicated. CD25, the IL-2R, is also expressed on effector T cells and is a marker of T cell activation. Elimination of this population from infected mice given rat IgG did not modulate the course of infection (see Figs. 5 and 6), whereas eliminating them from mice given mAb to TNF-α restored healing immunity as exemplified by a reduction in CFU and a prolonged survival. Because elimination of CD25+ cells from rat IgG-treated, infected mice did not modulate the fungal burden at all, the results suggest that this population of T cells is not critically important for host control of infection in otherwise normal mice. Rather, the CD25+ population manifests detrimental effects when the biological activity of TNF-α has been antagonized. Although several different functional cell populations were eliminated by mAb to CD25, the principal effect on the infection was in the depletion of the regulatory population.

Several endogenous cytokines are necessary for the expression of healing immunity in murine histoplasmosis including IFN-γ (via IL-12), GM-CSF, and TNF-α (6, 7, 10, 12, 50). The failure to eliminate the fungus when these cytokines are lacking or their activity is inhibited is accompanied by an increased fungal burden; nevertheless, only inhibition of TNF-α induced an increase in CD4+CD25+ cells. Challenge of immunocompetent mice with a high inoculum that produced a burden (log10 CFU 7.9 ± 0.7) at day 7, similar to that observed in mice given mAb to TNF-α, IFN-γ, or GM-CSF, did not increase CD4+CD25+ cells. Furthermore, depletion of the CD25+ cell population did not restore immunity in IFN-γ-neutralized mice or in mice given 107 yeasts. In fact, IFN-γ has been reported to be an enabler of Treg function (51). Accordingly, the emergence of inhibitory T cells is simply not a result of an increased fungal burden as has been shown in the systemic model of murine histoplasmosis (52).

Systemic infection of normal mice with H. capsulatum induces a population of CD8+ T cells in the spleen that inhibit cellular immune responses nonspecifically (52, 53). By contrast, we were unable to identify a regulatory population in normal mice when infected via the intranasal route. These results suggest that the requirements for generation of T cells that dampen immunity may be dependent on the route of inoculation, the target organ, or both. Additional differences distinguish our results from the previous findings. First, the inhibitory T cells manifested a different phenotype. Second, their emergence was dependent on TNF-α antagonism, and third, they exerted Ag-specific suppression.

In vitro and in vivo studies demonstrated that suppression was mediated largely, if not exclusively, by IL-10, as exemplified by reversal of suppression by mAb to IL-10. This cytokine has been shown in other models to be an important mediator of the immunosuppressive properties of these cells (24, 25, 32). Infection with H. capsulatum is associated with a vigorous production of IFN-γ, but not IL-10, in vivo (26, 54). The number of IL-10 producing cells is small and appears to be principally located within the phagocyte population (54). In a previous report, we also were unable to demonstrate an increase in IL-10 production in naive infected or uninfected mice given mAb to TNF-α (6). However, we have clearly demonstrated that TNF-α neutralization was clearly accompanied by an increase in the frequency of CD4+CD25+ cells that secrete IL-10. It is possible that the functional properties of IL-10 from CD4+CD25+ cells are exaggerated when TNF-α is diminished or absent. In contrast, IL-10 and IL-4 are both increased in secondary infection, yet only neutralization of IL-10 modified the inhibitory activity of CD4+CD25+ cells (6).

The mechanisms by which IL-10 alter host defenses to this fungus remain to be precisely determined. Despite its known anti-inflammatory properties, IL-10 does not inhibit the influx of inflammatory cells into the lungs of mice infected with H. capsulatum. Moreover, it does not depress the levels of IFN-γ in lungs (6). One possibility to account for the harmful effects of IL-10 from CD4+CD25+ cells is that the cytokine induces the gene for suppressor cytokine synthesis 3, which in turn may interfere with IFN-γ signaling (55). Thus, IFN-γ would be unable to salvage host defenses when TNF-α is depressed. Since IL-10 can also alter the antimicrobial properties of phagocytes, it is also possible that release of this cytokine in tissue leads to dysfunctional effector cells (56-58).

Mice genetically deficient in IL-10 are less susceptible to infection with H. capsulatum (59). The salutary effect is noted during the activation of cellular immunity rather than during the innate response. Neutralization of TNF-α can overcome the beneficial effect associated with the absence of IL-10. The IL-10-/- mice succumb to overwhelming histoplasmosis even in the absence of IL-10. These results suggest that alternative mediators, such as TGF-β or IL-9, may be responsible for impaired immunity when IL-10 is absent and TNF-α is antagonized.

In earlier studies, we reported that one cause of the aggressive nature of histoplasmosis in naive recipients of mAb to TNF-α was a decrement in NO, which is a crucial mediator of host defenses to this fungus (12). In secondary histoplasmosis in mice, release of NO is not altered, and it does not seem to be an important mediator of host defenses. This molecule has been reported to promote the Th1 cell differentiation and to enhance the emergence of Tregs (60, 61). In the case of primary infection with H. capsulatum, our results are dissimilar from those findings especially regarding the necessity of NO for Treg.

CD103 is a homing receptor that is present on T cells including Tregs (62). This receptor has been reported to enhance retention of naturally occurring Tregs at the site of inflammation (62). Surprisingly, treatment with mAb to TNF-α reduced the number of CD4+CD25+ cells that bore this surface receptor in both primary and secondary infection. The decrement in the number of expressing cells was not anticipated, and the finding indicates that TNF-α may regulate expression of the homing receptors. In support of this contention, a different TNF-antagonist, TNF-binding protein diminishes expression of VCAM-1, ICAM-1, and VLA-1 (63). The findings also suggest that Treg found in the lungs of infected mice did not accumulate because of enhanced expression of CD103.

The emergence of this Treg population may be a result of either de novo induction or accrual and expansion at the site of the infection. Natural Tregs arise as a committed population in the thymus, whereas induced Tregs appear to arise without a thymic precursor (64, 65). Accumulation of Ag-specific Tregs has been reported to be restricted infected tissues in murine leishmaniasis (66). This work did not directly distinguish between an induced population and expansion of a pre-existing one. However, the fact that we did not find an accumulation of CD4+CD25+ cells in uninfected animals (G. Deepe, data not shown) or evidence for a regulatory population in infected controls suggests that the absence of TNF-α imparts the appropriate conditions for the emergence of these regulatory cells. Nevertheless, the presence of this population does play a significant role in modulating fungal immunity to this pathogen.

Our findings extend observations made in humans and in mice concerning the importance of TNF-α or its absence in influencing the emergence of T cells with immunoregulatory properties. Much of the prior work has demonstrated that neutralization of TNF-α in inflammatory conditions promotes the expansion of Tregs. Likewise, we found that a Treg population was expanded in the lungs of mice infected with H. capsulatum and given mAb to TNF-α. In contrast to others, the population we detected was not characteristic of a natural Treg. Interestingly, the CD4+CD25+ cells suppressed in an Ag-specific manner, although Ag-specific Tregs have been reported (66). In contrast to our findings in which the neutralization of TNF-α induced the emergence of a suppressive population, engagement of TNF with TNFR2 in the absence of a disease condition is reported to enhance the expansion and functional properties of Tregs (67). It is possible that the regulatory properties of TNF on CD4+CD25+ cells may differ depending on the presence or absence of disease.

In summary, we have reported that antagonism of TNF-α by mAb induces the appearance of a regulatory population of T cells that exhibit an effector phenotype and that can dampen immunity to H. capsulatum. The outgrowth of this population appears to be specific for TNF-α and is observed in both naive and immune animals. The regulatory properties of the T cells are Ag specific. This work thus extends the complexities of the immunological disturbances associated with neutralization of TNF-α.

Footnotes

This work was supported by a Merit Review Grant from the Veterans Affairs and National Institutes of Health Grants AI061298, AI34361, and AI42747.

- Treg

- regulatory T cell

- GITR

- glucocorticoid inducible TNFR

- i.n.

- intranasally

The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked advertisement in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Disclosures

The authors have no financial conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Deepe GS., Jr. Histoplasma capsulatum. In: Mandell GL, Bennett JE, Dolin R, editors. Principles and Practices of Infectious Diseases. Vol. 2. Elsevier Churchill Livingstone; Philadelphia: 2004. pp. 3012–3026. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Limaye AP, Connolly PA, Sagar M, Fritsche TR, Cookson BT, Wheat LJ, Stamm WE. Transmission of Histoplasma capsulatum by organ transplantation. N. Engl. J. Med. 2000;343:1163–1166. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200010193431605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gildea LA, Ciraolo GM, Morris RE, Newman SL. Human dendritic cell activity against Histoplasma capsulatum is mediated via phagolysosomal fusion. Infect. Immun. 2005;73:6803–6811. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.10.6803-6811.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Newman SL, Bucher C, Rhodes J, Bullock WE. Phagocytosis of Histoplasma capsulatum yeasts and microconidia by human cultured macrophages and alveolar macrophages: cellular cytoskeleton requirement for attachment and ingestion. J. Clin. Invest. 1990;85:223–230. doi: 10.1172/JCI114416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Allendorfer R, Brunner GD, Deepe GS., Jr. Complex requirements for nascent and memory immunity in pulmonary histoplasmosis. J. Immunol. 1999;162:7389–7396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Allendoerfer R, Deepe GS., Jr. Blockade of endogenous TNF-α exacerbates primary and secondary pulmonary histoplasmosis by differential mechanisms. J. Immunol. 1998;160:6072–6082. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deepe GS, Jr., Gibbons R, Woodward E. Neutralization of endogenous granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor subverts the protective immune response to Histoplasma capsulatum. J. Immunol. 1999;163:4985–4993. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deepe GS, Jr., McGuinness M. Interleukin-1 and host control of pulmonary histoplasmosis. J. Infect. Dis. 2006;194:855–864. doi: 10.1086/506946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wu-Hsieh BA, Howard DH. Inhibition of the intracellular growth of Histoplasma capsulatum by recombinant murine γ interferon. Infect. Immun. 1987;55:1014–1016. doi: 10.1128/iai.55.4.1014-1016.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wu-Hsieh BA, Lee GS, Franco M, Hofman FM. Early activation of splenic macrophages by tumor necrosis factor α is important in determining the outcome of experimental histoplasmosis in mice. Infect. Immun. 1992;60:4230–4238. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.10.4230-4238.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhou P, Miller G, Seder RA. Factors involved in regulating primary and secondary immunity to infection with Histoplasma capsulatum: TNF-α plays a critical role in maintaining secondary immunity in the absence of IFN-γ. J. Immunol. 1998;160:1359–1368. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhou P, Sieve MC, Bennett J, Kwon-Chung KJ, Tewari RP, Gazzinelli RT, Sher A, Seder RA. IL-12 prevents mortality in mice infected with Histoplasma capsulatum through induction of IFN-γ. J. Immunol. 1995;155:785–795. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lin JS, Yang CW, Wang DW, Wu-Hsieh BA. Dendritic cells cross-present exogenous fungal antigens to stimulate a protective CD8 T cell response in infection by Histoplasma capsulatum. J. Immunol. 2005;174:6282–6291. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.10.6282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Medeiros AI, Sa-Nunes A, Soares EG, Peres CM, Silva CL, Faccioli LH. Blockade of endogenous leukotrienes exacerbates pulmonary histoplasmosis. Infect. Immun. 2004;72:1637–1644. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.3.1637-1644.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhou P, Freidag BL, Caldwell CC, Seder RA. Perforin is required for primary immunity to Histoplasma capsulatum. J. Immunol. 2001;166:1968–1974. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.3.1968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee JH, Slifman NR, Gershon SK, Edwards ET, Schwieterman WD, Siegel JN, Wise RP, Brown SL, Udall JN, Jr., Braun MM. Life-threatening histoplasmosis complicating immunotherapy with tumor necrosis factor α antagonists infliximab and etanercept. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46:2565–2570. doi: 10.1002/art.10583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sieper J, Van Den Brande J. Diverse effects of infliximab and etanercept on T lymphocytes. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;34:23–27. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2005.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Anderson PJ. Tumor necrosis factor inhibitors: clinical implications of their different immunogenicity profiles. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;34:19–22. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2005.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wood KL, Hage CA, Knox KS, Kleiman MB, Sannuti A, Day RB, Wheat LJ, Twigg HL., III Histoplasmosis after treatment with anti-tumor necrosis factor-α therapy. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2003;167:1279–1282. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200206-563OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Deepe GS, Jr., Gibbons RS. T cells require tumor necrosis factor-α to provide protective immunity in mice infected with Histoplasma capsulatum. J. Infect. Dis. 2006;193:322–330. doi: 10.1086/498981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Valencia X, Stephens G, Goldbach-Mansky R, Wilson M, Shevach EM, Lipsky PE. TNF downmodulates the function of human CD4+CD25hi T-regulatory cells. Blood. 2006;108:253–261. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-11-4567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wu AJ, Hua H, Munson SH, McDevitt HO. Tumor necrosis factor-α regulation of CD4+CD25+ T cell levels in NOD mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:12287–12292. doi: 10.1073/pnas.172382999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ehrenstein MR, Evans JG, Singh A, Moore S, Warnes G, Isenberg DA, Mauri C. Compromised function of regulatory T cells in rheumatoid arthritis and reversal by anti-TNF-α therapy. J. Exp. Med. 2004;200:277–285. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Belkaid Y, Piccirillo CA, Mendez S, Shevach EM, Sacks DL. CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells control Leishmania major persistence and immunity. Nature. 2002;420:502–507. doi: 10.1038/nature01152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kursar M, Koch M, Mittrucker HW, Nouailles G, Bonhagen K, Kamradt T, Kaufmann SH. Regulatory T cells prevent efficient clearance of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Immunol. 2007;178:2661–2665. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.5.2661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cain JA, Deepe GS., Jr. Evolution of the primary immune response to Histoplasma capsulatum in murine lung. Infect. Immun. 1998;66:1473–1481. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.4.1473-1481.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Deepe GS, Jr., Smith JG, Sonnenfeld G, Denman D, Bullock WE. Development and characterization of Histoplasma capsulatum-reactive murine T-cell lines and clones. Infect. Immun. 1986;54:714–722. doi: 10.1128/iai.54.3.714-722.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gomez AM, Rhodes JC, Deepe GS., Jr. Antigenicity and immunogenicity of an extract from the cell wall and cell membrane of Histoplasma capsulatum yeast cells. Infect. Immun. 1991;59:330–336. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.1.330-336.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ortega G, Robb RJ, Shevach EM, Malek TR. The murine IL 2 receptor, I: monoclonal antibodies that define distinct functional epitopes on activated T cells and react with activated B cells. J. Immunol. 1984;133:1970–1975. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Luhn K, Simmons CP, Moran E, Dung NT, Chau TN, Quyen NT, Thao LT, Van Ngoc T, Dung NM, Wills B, et al. Increased frequencies of CD4+CD25high regulatory T cells in acute dengue infection. J. Exp. Med. 2007;204:979–985. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Abidi FE, Roh H, Keath EJ. Identification and characterization of a phase-specific, nuclear DNA binding protein from the dimorphic pathogenic fungus Histoplasma capsulatum. Infect. Immun. 1998;66:3867–3873. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.8.3867-3873.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Belkaid Y, Rouse BT. Natural regulatory T cells in infectious disease. Nat. Immunol. 2005;6:353–360. doi: 10.1038/ni1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Belkaid Y. The role of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells in Leishmania infection. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 2003;3:875–885. doi: 10.1517/14712598.3.6.875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marie JC, Letterio JJ, Gavin M, Rudensky AY. TGF-β1 maintains suppressor function and Foxp3 expression in CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells. J. Exp. Med. 2005;201:1061–1067. doi: 10.1084/jem.20042276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lu LF, Lind EF, Gondek DC, Bennett KA, Gleeson MW, Pino-Lagos K, Scott ZA, Coyle AJ, Reed JL, Van Snick J, et al. Mast cells are essential intermediaries in regulatory T-cell tolerance. Nature. 2006;442:997–1002. doi: 10.1038/nature05010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Montagnoli C, Fallarino F, Gaziano R, Bozza S, Bellocchio S, Zelante T, Kurup WP, Pitzurra L, Puccetti P, Romani L. Immunity and tolerance to Aspergillus involve functionally distinct regulatory T cells and tryptophan catabolism. J. Immunol. 2006;176:1712–1723. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.3.1712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Feldmann M, Maini RN. Anti-TNF α therapy of rheumatoid arthritis: what have we learned? Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2001;19:163–196. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.19.1.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Keane J, Gershon S, Wise RP, Mirabile-Levens E, Kasznica J, Schwieterman WD, Siegel JN, Braun MM. Tuberculosis associated with infliximab, a tumor necrosis factor α-neutralizing agent. N. Engl. J. Med. 2001;345:1098–1104. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Trent JT, Kerdel FA. Tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors for the treatment of dermatologic diseases. Dermatol. Nurs. 2005;17:97–107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wallis RS, Broder MS, Wong JY, Hanson ME, Beenhouwer DO. Granulomatous infectious diseases associated with tumor necrosis factor antagonists. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2004;38:1261–1265. doi: 10.1086/383317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Malek TR, Bayer AL. Tolerance, not immunity, crucially depends on IL-2. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2004;4:665–674. doi: 10.1038/nri1435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Huang CT, Workman CJ, Flies D, Pan X, Marson AL, Zhou G, Hipkiss EL, Ravi S, Kowalski J, Levitsky HI, et al. Role of LAG-3 in regulatory T cells. Immunity. 2004;21:503–513. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fontenot JD, Gavin MA, Rudensky AY. Foxp3 programs the development and function of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells. Nat. Immunol. 2003;4:330–336. doi: 10.1038/ni904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sakaguchi S. Naturally arising CD4+ regulatory T cells for immunologic self-tolerance and negative control of immune responses. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2004;22:531–562. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.21.120601.141122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Von Boehmer H. Mechanisms of suppression by suppressor T cells. Nat. Immunol. 2005;6:338–344. doi: 10.1038/ni1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mittrucker HW, Kaufmann SH. Mini-review: regulatory T cells and infection; suppression revisited. Eur. J. Immunol. 2004;34:306–312. doi: 10.1002/eji.200324578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rouse BT, Suvas S. Regulatory cells and infectious agents: detentes cordiale and contraire. J. Immunol. 2004;173:2211–2215. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.4.2211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Anderson CF, Oukka M, Kuchroo VJ, Sacks D. CD4+CD25- Foxp3- Th1 cells are the source of IL-10-mediated immune suppression in chronic cutaneous leishmaniasis. J. Exp. Med. 2007;204:285–297. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jankovic D, Kullberg MC, Feng CG, Goldszmid RS, Collazo CM, Wilson M, Wynn TA, Kamanaka M, Flavell RA, Sher A. Conventional T-bet+ Foxp3- Th1 cells are the major source of host-protective regulatory IL-10 during intracellular protozoan infection. J. Exp. Med. 2007;204:273–283. doi: 10.1084/jem.20062175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wu-Hsieh BA, Chen W, Lee HJ. Nitric oxide synthase expression in macrophages of Histoplasma capsulatum-infected mice is associated with splenocyte apoptosis and unresponsiveness. Infect. Immun. 1998;66:5520–5526. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.11.5520-5526.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wood KJ, Sawitzki B. Interferon γ: a crucial role in the function of induced regulatory T cells in vivo. Trends Immunol. 2006;27:183–187. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2006.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Artz RP, Bullock WE. Immunoregulatory responses in experimental disseminated histoplasmosis: depression of T-cell-dependent and T-effectory responses by activation of splenic suppressor cells. Infect. Immun. 1979;23:893–902. doi: 10.1128/iai.23.3.893-902.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Watson SR, Bullock WE. Immunoregulation in disseminated histoplasmosis: characterization of the surface phenotype of splenic suppressor T lymphocytes. Infect. Immun. 1982;37:940–945. doi: 10.1128/iai.37.3.940-945.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Peng JK, Lin JS, Kung JT, Finkelman FD, Wu-Hsieh BA. The combined effect of IL-4 and IL-10 suppresses the generation of, but does not change the polarity of, type-1 T cells in Histoplasma infection. Int. Immunol. 2005;17:193–205. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxh200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Crespo A, Filla MB, Murphy WJ. Low responsiveness to IFN-γ, after pretreatment of mouse macrophages with lipopolysaccharides, develops via diverse regulatory pathways. Eur. J. Immunol. 2002;32:710–719. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200203)32:3<710::AID-IMMU710>3.0.CO;2-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rojas M, Olivier M, Gros P, Barrera LF, Garcia LF. TNF-α and IL-10 modulate the induction of apoptosis by virulent Mycobacterium tuberculosis in murine macrophages. J. Immunol. 1999;162:6122–6131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Moore KW, de Waal Malefyt R, Coffman RL, O’Garra A. Interleukin-10 and the interleukin-10 receptor. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2001;19:683–765. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.19.1.683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jimenez Mdel P, Walls L, Fierer J. High levels of interleukin-10 impair resistance to pulmonary coccidioidomycosis in mice in part through control of nitric oxide synthase 2 expression. Infect. Immun. 2006;74:3387–3395. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01985-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Deepe GS, Jr., Gibbons RS. Protective and memory immunity to Histoplasma capsulatum in the absence of IL-10. J. Immunol. 2003;171:5353–5362. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.10.5353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Niedbala W, Cai B, Liew FY. Role of nitric oxide in the regulation of T cell functions. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2006;65(Suppl 3):iii37–iii40. doi: 10.1136/ard.2006.058446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Niedbala W, Wei XQ, Campbell C, Thomson D, Komai-Koma M, Liew FY. Nitric oxide preferentially induces type 1 T cell differentiation by selectively up-regulating IL-12 receptor β 2 expression via cGMP. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:16186–16191. doi: 10.1073/pnas.252464599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Suffia I, Reckling SK, Salay G, Belkaid Y. A role for CD103 in the retention of CD4+CD25+ Treg and control of Leishmania major infection. J. Immunol. 2005;174:5444–5455. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.9.5444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Selmaj K, Walczak A, Mycko M, Berkowicz T, Kohno T, Raine CS. Suppression of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis with a TNF binding protein (TNFbp) correlates with down-regulation of VCAM-1/VLA-4. Eur. J. Immunol. 1998;28:2035–2044. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199806)28:06<2035::AID-IMMU2035>3.0.CO;2-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zhou G, Levitsky HI. Natural regulatory T cells and de novo-induced regulatory T cells contribute independently to tumor-specific tolerance. J. Immunol. 2007;178:2155–2162. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.4.2155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Fontenot JD, Rasmussen JP, Williams LM, Dooley JL, Farr AG, Rudensky AY. Regulatory T cell lineage specification by the forkhead transcription factor foxp3. Immunity. 2005;22:329–341. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Suffia IJ, Reckling SK, Piccirillo CA, Goldszmid RS, Belkaid Y. Infected site-restricted Foxp3+ natural regulatory T cells are specific for microbial antigens. J. Exp. Med. 2006;203:777–788. doi: 10.1084/jem.20052056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Chen X, Baumel M, Mannel DN, Howard OM, Oppenheim JJ. Interaction of TNF with TNF receptor type 2 promotes expansion and function of mouse CD4+CD25+ T regulatory cells. J. Immunol. 2007;179:154–161. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.1.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]