Abstract

Formation of discoidal high density lipoproteins (rHDL) by apolipoprotein A-I (apoA-I) mediated solubilization of dimyristoyl phosphatidylcholine (DMPC) multilamellar vesicles (MLV) was dramatically affected by bilayer cholesterol concentration. At a low ratio of DMPC/apoA-I (2 mg DMPC/mg apoA-I, 84/1 mol/mol), sterols (cholesterol, lathosterol, and β-sitosterol) that form ordered lipid phases increase the rate of solubilization similarly, yielding rHDL with similar structures. By changing the temperature and sterol concentration, the rates of solubilization varied almost 3 orders of magnitude; however, the sizes of the rHDL were independent of the rate of their formation and dependent upon the bilayer sterol concentration. At a high ratio of DMPC/apoA-I (10/1 mg DMPC/mg apoA-I, 420/1 mol/mol), changing the temperature and cholesterol concentration yielded rHDL that varied greatly in size, phospholipid/protein ratio, mol% cholesterol, and number of apoA-I molecules per particle. rHDL were isolated that had 2, 4, 6, and 8 molecules of apoA-I per particle, mean diameters of 117, 200, 303, and 396 Å, and a mol% cholesterol that was similar to the original MLV. Kinetic studies demonstrated the different sized rHDL are formed independently and concurrently. The rate of formation, lipid composition, and three-dimensional structures of cholesterol-rich rHDL are dictated primarily by the original membrane phase properties and cholesterol content. The size speciation of rHDL and probably nascent HDL formed via the activity of the ABCA1 lipid transporter are mechanistically linked to the cholesterol content of the membranes from which they were formed.

Keywords: Reverse cholesterol transport, apoA-I, cholesterol, high density lipoprotein, phosphatidylcholines, microsolubilization

1. Introduction

Apolipoprotein A-I is the major protein component of plasma high density lipoproteins. ApoA-I mediates reverse cholesterol transport [1–3], the process by which cholesterol in peripheral tissue, e.g. macrophage foam cells, is transported to the liver for recycling or catabolism to bile acids, which are excreted. An initial step in RCT is the lipidation of apoA-I with cellular phospholipids and cholesterol to form discoidal nascent HDL [3]. This is catalyzed by the ABCA1 lipid transporter and is essential to the formation of plasma HDL and for the removal of excess cholesterol from macrophage-foam cells [4–6]. However, this process is not specific for apoA-I since other apolipoproteins, apolipoprotein structural mutants, and synthetic peptides also induce ABCA1 dependent lipid efflux [3, 7–11]. ApoA-I demonstrates two high affinity cell surface binding sites which indicate that apoA-I has two separate and independent functions in ABCA1 mediated lipidation [3, 12, 13]. First, apoA-I directly binds to ABCA1 which has been proposed to serve a regulatory role to decrease ABCA1 protein turnover and enhance lipid translocase activity. At a second high capacity site which is created by the phospholipid translocase activity of ABCA1, apoA-I through lipid-protein interactions associates with membrane domains that are involved in the assembly of nascent HDL particles. ApoA-I [14, 15–17] and other apolipoproteins [18–20] can spontaneously solubilize bilayer membranes of DMPC and other phospholipid mixtures [3, 21, 22] to form discoidal rHDL. In one model for ABCA1, apoA-I via a microsolubilization step simultaneously removes phospholipid and cholesterol from ABCA1 created membrane domains to form nascent HDL by the same mechanism by which apoA-I mediates the solubilization of DMPC MLV to form rHDL. In this proposed mechanism, the activity of ABCA1 generates a membrane environment that allows apoA-I or other apolipoproteins to overcome the rate-limiting step of penetration into a membrane surface. However, once this kinetic barrier is overcome, the HDL products are determined by the intrinsic structural properties of an apolipoprotein to interact with phospholipids and form lipid/protein particles.

The apoA-I molecules in similar sized discoidal HDL particles formed by cholate removal methods [23, 24], by spontaneous membrane solubilization [3, 14, 17, 21], and by ABCA1 [3, 25, 26] are thought to have the same structural organization. Structural models of apoA-I in discoidal rHDL have been developed primarily using particles (diameter of 96 Å) that contain two molecules of apoA-I with 150–160 molecules of phospholipid [14, 23, 24, 27]. The two apoA-I molecules wrap around a lipid bilayer disk forming two stacked rings (double belt) in an antiparallel orientation. However, larger sized rHDL containing 3 and 4 molecules of apoA-I can be formed in the presence of cholesterol both by DMPC solubilization [28–30] and by cholate dialysis methods [31, 32]. Incubating apoA-I with cells expressing ABCA1 also generates numerous discrete particles that vary in size (diameters from ~ 90–200 Å) and number of apoA-I molecules (from 2 to 8 molecules) [25, 26, 33, 34]. Thus, ABCA1 formed nascent HDL and cholesterol-rich rHDL demonstrate size speciation and apoA-I structural organization that are different form the well studied rHDL containing 2 molecules of apoA-I.

In this report, the spontaneous solubilization of DMPC MLV by apoA-I was used to determine how sterol structure and concentration regulate the formation of rHDL. Similar to other studies, the rates of solubilization were highly dependent upon temperature and sterol concentration [28–30]. Cholesterol, lathosterol and β-sitosterol, all which form ordered lipid phases, enhance the rate of solubilization. The size and lipid composition of the rHDL were independent of the rate of their formation, but did depend upon the original sterol content in DMPC MLV. Discoidal cholesterol-rich rHDL that varied in size (diameter ~ 100 to 400 Å) and number of apoA-I molecules (2 to 8 per particle) were formed, where the mol% cholesterol in isolated rHDL was the same as in the original DMPC MLV. The even number of apoA-I molecules suggest multiple copies of apoA-I in a double belt configuration [2, 14, 23, 24, 27]. Additionally, the different sized rHDL did not demonstrate a precursor-product relationship which indicated they were formed independently and concurrently. Our results indicate that the size speciation of discoidal rHDL formed by DMPC solubilization and probably nascent HDL formed by membrane microsolubilization is mechanistically linked to the cholesterol content of the membranes from which they were formed.

2. Materials and methods

2.1 Materials

ApoA-I was isolated from human plasma as previously described and its concentration was determined spectroscopically using ε280 = 30,700 M−1cm−1 [30]. DMPC and 1-myristoyl-2- hydroxy-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine were from Avanti Polar Lipids, Inc. (Alabaster, AL). [3H]Myristic acid was from American Radiolabeled Chemicals, Inc. (St. Louis, MO). Cholesterol was from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO), lathosterol was from Steraloids, Inc. (Newport, RI), and synthetic β-sitosterol was from Fluka Chemical Corp. (Milwaukee, WI). DPH was from Molecular Probes, Inc. (Eugene, OR). [3H]DMPC was synthesized from 1-myristoyl-2- hydroxy-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine and [3H]myristic acid and was purified using previously published procedures [35].

2.2 Preparation of Multilamellar Phospholipid Vesicles

DMPC and DMPC/sterol MLV were prepared by mixing the appropriate amounts of phospholipid and sterol in chloroform/methanol (2/1 v/v). The organic solvent was evaporated under a stream of nitrogen and the samples were lyophilized overnight. The dried lipids were dispersed in TBS buffer (100 mM NaCl, 10 mM Tris, 1 mM EDTA, 1mM NaN3, pH 7.4) by vortexing. To ensure complete hydration, the lipids were subjected to at least 3 freeze-thaw cycles that consisted of warming the samples to 37 °C, repeated vortexing of the samples at this temperature, and then freezing the samples at −20 °C.

2.3 Kinetics of ApoA-I Mediated Solubilization of DMPC MLV Determined by Right-Angle Light Scattering

The kinetics for the solubilization of DMPC and DMPC/sterol MLV by apoA-I was measured in a Jobin Yvon Spex Fluorolog®-3 FL3-22 spectrofluorimeter (Edison, NJ) where the temperature of the sample compartment was maintained by using a heater/cooler Peltier thermocouple drive [29, 30]. Kinetic measurements were made by following the time-dependent reduction in right-angle light scattering with the excitation and emission wavelengths set at 325 nm. Changes in light scattering were due to the conversion of the large MLV (diameter ~10,000 Å) that scatter light to small rHDL (diameter ~100 – 200 Å) that do not. The MLV were preincubated at the appropriate temperature and mixed with apoA-I to a final concentration of 0.5 mg of DMPC and 0.25 mg of apoA-I (weight ratio of 2 mg DMPC/mg apoA-I, molar ratio of 84/1 mol/mol) in a final volume of 3 mL. The samples were continuously stirred to prevent the settling of the MLV. The data were analyzed to determine a kinetic half-time (t1/2), which was the time required for a 50% decrease in the right-angle light scattering intensity. The apparent rate of solubilization of DMPC MLV was defined as rate = 1/t1/2. Changes in right-angle light scattering do not directly correlate with the formation of rHDL because this measurement is predominately determined by the amount and size of the MLV present. Thus, it is difficult to analyze the data as one type of process (i.e. single exponential) when the apparent rates vary so greatly. Measured half-times for multiple samples of DMPC MLV had 1/t1/2 values that were within ±15% of each other.

2.4 ApoA-I Mediated Solubilization of DMPC MLV Determined by Centrifugation

For the apoA-I mediated solubilization of DMPC/sterol MLV, the effects of varying the experimental conditions of (a) the phospholipid/apoA-I ratio, (b) the amount of cholesterol, and (c) the time dependence was determined by using centrifugation. In this method, unreacted DMPC/sterol MLV were removed by centrifugation [36] and the supernatant analyzed for the amount of phospholipid solubilized by rHDL formation and for rHDL particle size by native PAGE analysis. To vary the phospholipid/apoA-I ratio (2 to 10 mg DMPC/mg apoA-I, 84/1 to 420/1 mol/mol) and the amount of cholesterol (0 to 30 mol% at 10 mg DMPC/mg apoA-I, 420/1 mol/mol), samples (0.2 ml) containing apoA-I (0.1 mg) and DMPC/sterol MLV were mixed and incubated for 20 hr at a specific temperature. The samples contained a trace amount of [3H]DMPC to quantitate the amount of phospholipid. The samples were then centrifuged at 16,000 × g for 30 min in an Eppendorf 5415 C centrifuge that was maintained at 4 °C in a cold room. Centrifugation sediments the unreacted DMPC/sterol MLV and leaves the rHDL in the supernatant. Aliquots from the supernatants were analyzed by scintillation counting to determine the amount of DMPC solubilized and for rHDL size analysis (6 µg apoA-I per sample) by native PAGE. The kinetics of rHDL formation were determined under conditions of excess phospholipid (10 mg DMPC/mg apoA-I, 420/1 mol/mol) at 22.0, 24.0, and 28.0 °C. Samples (6.0 mg DMPC and 0.6 mg apoA-I in 1.2 mls) were continuously stirred and the temperature maintained in the sample compartment of the Fluorolog®-3 FL3-22 spectrofluorimeter. At the appropriate time, a 100 µl aliquot was removed and placed in an ice cold microcentrifuge tube, centrifuged at 16,000 × g for 30 min at 4 °C to pellet unreacted MLV, and the supernatants analyzed for the DMPC concentration by scintillation counting and the size of the rHDL formed by native PAGE.

rHDL reaction products were analyzed by native PAGE on 4–15% gradient gels (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). Samples were mixed equally with native sample buffer (Bio-Rad) that contained 1 M urea to eliminate lipid free apoA-I self-association. Gels were fixed with 7% acetic acid and 50% methanol and protein bands visualized with Gelcode blue stain reagent (Pierce Biotechnology, Inc. Rockford, IL). High molecular weight standards of diameters 170, 122, 104, 82, and 71 Å (HMW calibration kit, GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ) were used to estimate the size of the rHDL.

2.5 Isolation and Characterization of rHDL

rHDL were isolated by size exclusion chromatography on two Superose 6 columns ran in tandem on an AKTA FPLC (GE Healthcare). ApoA-I was mixed and incubated for 20 hr with DMPC MLV (10 mg DMPC/mg apoA-I, 420/1 mol/mol) at 22.0, 24.0, 25.0, and 28.0 °C, with DMPC MLV containing 5, 10, 15, and 20 mol% cholesterol at 24.0 and 25.0 °C, and with DMPC MLV containing 5 and 10 mol% cholesterol at 28.0 °C. The incubation mixtures consisted of 3 mg apoA-I and 30 mg DMPC in 3 ml. After the incubations, the samples were centrifuged at 16,000 × g for 30 min at 4 °C in an Eppendorf 5415 microcentrifuge to remove unreacted MLV, the samples concentrated to 1 ml using Amicon Ultra-4 centrifugal filter devices, and applied in two sequential runs on the FPLC using a 500 µl sample loop. The elution of rHDL was followed by the absorbance at 280 nm. Four major apoA-I containing fractions were identified and denoted rHDL Fractions 1, 2, 3, and 4. The pooled fractions were analyzed for protein, cholesterol, and phospholipid content using commercial kits (Bio-Rad Laboratories and Wako Chemicals USA, Inc., Richmond, VA), by native PAGE, and by a second analytical run (using a 200 µl sample loop) to determine the elution volume for the maxima of the protein peak.

2.6 Negative Staining Electron Microscopy

Isolated rHDL Fractions were analyzed by negative staining electron microscopy [26, 37]. Samples (0.5–1 mg/ml) were dialyzed against 0.125 M ammonium acetate, 2.6 mM ammonium carbonate, and 0.26 mM tetrasodium EDTA, pH 7.4, at 4 °C overnight. A 4 µL aliquot of sample was applied to a freshly glow-discharged, carbon and Formvar-coated, 300 mesh copper grid (Ted Pella, Inc. Redding, CA) for 30 s. After blotting excess fluid, the sample was stained with 4 µL of 2 % sodium phosphotungstate (negative stain) (pH 7.4) for 10 s. Samples were then examined on a Hitachi H-7500 transmission electron microscope (Hitachi High Technologies America, Inc. San Jose, CA). Representative fields were photographed with an exposure time of 1.00 s at 42.5 K magnification. The measured diameters were used to estimate the number of apoA-I molecules per rHDL and the DMPC/apoA-I molar stoichiometry (mol /mol) (33, 37).

2.7 Cross-linking Studies

The number of apoA-I molecules per rHDL particle was determined by chemical cross-linking with bis(sulfosuccinimidyl) suberate (BS3) (Pierce Biotechnology Inc.) (33). rHDL (0.5 mg/ml apoA-I) in 10 mM Hepes, 100 mM NaCl, pH 7.4 were incubated at a molar ratio of 10/1 BS3/apoA-I for 2 and 20 hr incubations at room temperature. The reactions were terminated by the addition of 100 mM ethanolamine. The rHDL samples were analyzed on 4–15% gradient SDS-PAGE gels and stained to visualize the apoA-I bands. The degree of apoA-I oligomerization was determined by comparison with standards of known molecular weight (Precision Plus Protein Standards, Bio-Rad).

2.8 Polarization of DPH Fluorescence

The effect of cholesterol content upon the phase behavior and fluidity of rHDL was determined by measuring the fluorescence polarization of DPH using previously described procedures [30]. rHDL were labeled with DPH by adding an aliquot of the probe dissolved in ethanol directly to the sample where the probe to phospholipid molar ratio was 1/250 mol/mol.

3. Results

3.1 Kinetics of Solubilization of DMPC MLV by apoA-I

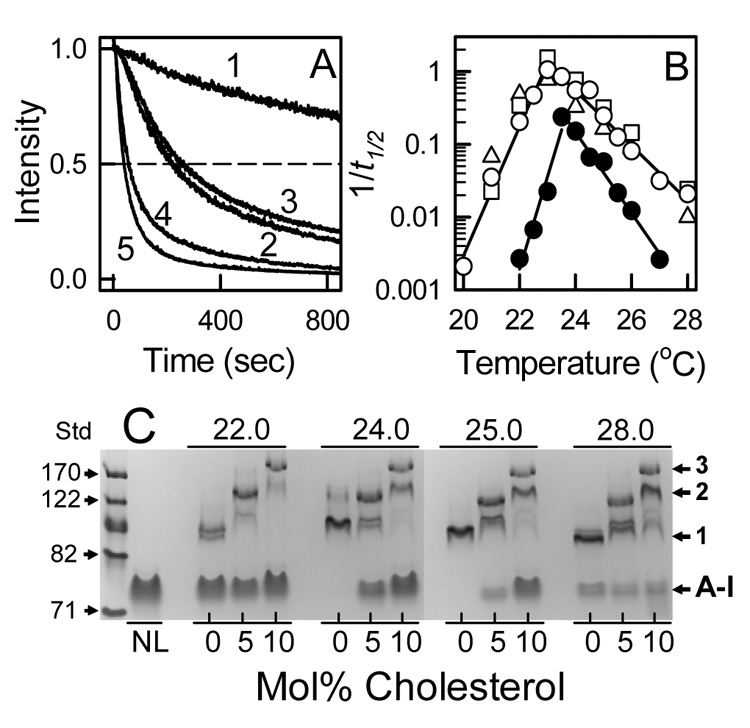

ApoA-I spontaneously solubilizes DMPC MLV to form rHDL which can be followed by the time dependent decrease in light scattering intensity (or turbidity) (Figure 1A). To have complete clearance of turbidity, 2 mg DMPC/mg apoA-I (84/1 mol/mol) was used. The addition of 5 and 10 mol% cholesterol increased the rate of clearance in a concentration dependent manner. Additionally, lathosterol and β-sitosterol demonstrated a similar behavior to cholesterol. For DMPC MLV, the rate of solubilization (rate = 1/t1/2) was fastest at 23.5 °C, which is the Tm for the so to ld phase transition of DMPC (Figure 1B). The rate was dramatically affected by changes in temperature, where the rate was ~ 90 fold slower both below (22.0 °C, so phase) and above (27.0 °C, ld phase) Tm. DMPC MLV which contained 10 mol% cholesterol had a maximum rate ~ 5 fold higher than sterol-free DMPC, however the rate was ~ 100 and 12 fold higher at 22.0 and 27.0 °C, respectively. Lathosterol and β-sitosterol demonstrated similar behavior (Figure 1B). rHDL particles formed by incubating apoA-I with DMPC MLV containing 0, 5, and 10 mol% cholesterol at 22.0, 24.0, 25.0, and 28.0 °C for 20 hr were analyzed by native PAGE (Figure 1C). The observed protein bands consisted of lipid-free apoA-I and three rHDL particles with diameters of 97.4 ± 5.4, 130 ± 3.8, and 170 ± 4.7 Å. The different rHDL probably contain 2, 3, and 4 apoA-I molecules per particle [31]. Three observations can be made from the native PAGE analysis. The size distributions of the rHDL were similar at each of the incubation temperatures, the particle sizes were a sensitive function of sterol content, and more lipid-free apoA-I was found as the amount of sterol is increased. Similar results were observed for lathosterol and β-sitosterol (data not shown). The kinetics of solubilization of DMPC and DMPC/sterol MLV by apoA-I varied almost three orders of magnitude as the temperature and sterol concentration were varied, however the speciation of the rHDL particles formed was determined by the original bilayer sterol concentration.

Figure 1.

Kinetics of ApoA-I Solubilization of DMPC MLV. A: Time dependent changes in light scattering intensity measured for DMPC MLV (trace 1) and DMPC MLV containing 5 (traces 2 & 3) and 10 (traces 4 & 5) mol% cholesterol (2 & 4) and lathosterol (traces 3 & 5) at 23.0 °C and at a weight ratio of 2 mg DMPC/mg apoA-I (84/1 mol/mol). Rates were determined as k = 1/t1/2 where t1/2 is the time to reach a 50% reduction in the light scattering intensity. B: The rates of apoA-I solubilization of DMPC MLV with no sterol (●) and with 10 mol% cholesterol (○), lathosterol (□), and β-sitosterol (△) measured as a function of temperature. Note that the 1/t1/2 values are on a logarithmic scale. For each of the sterols, the temperature dependence at 5 mol% sterol was intermediate between 0 and 10 mol% sterol (data not shown). C: rHDL formed by the solubilization of DMPC/cholesterol MLV by apoA-I were analyzed by native PAGE. The reaction temperatures and cholesterol contents of DMPC MLV are labeled; NL = lipid-free apoA-I ran as a standard. The molecular weight standards (Std) are 71, 82, 104, 122, and 170 Å. The rHDL bands 1, 2, and 3 had apparent diameters of 97.8 ± 5.4, 130 ± 3.8, and 170 ± 4.7 Å (mean ± S.D.), respectively.

3.2 Effect of Phospholipid and Cholesterol Concentration on the Formation of rHDL

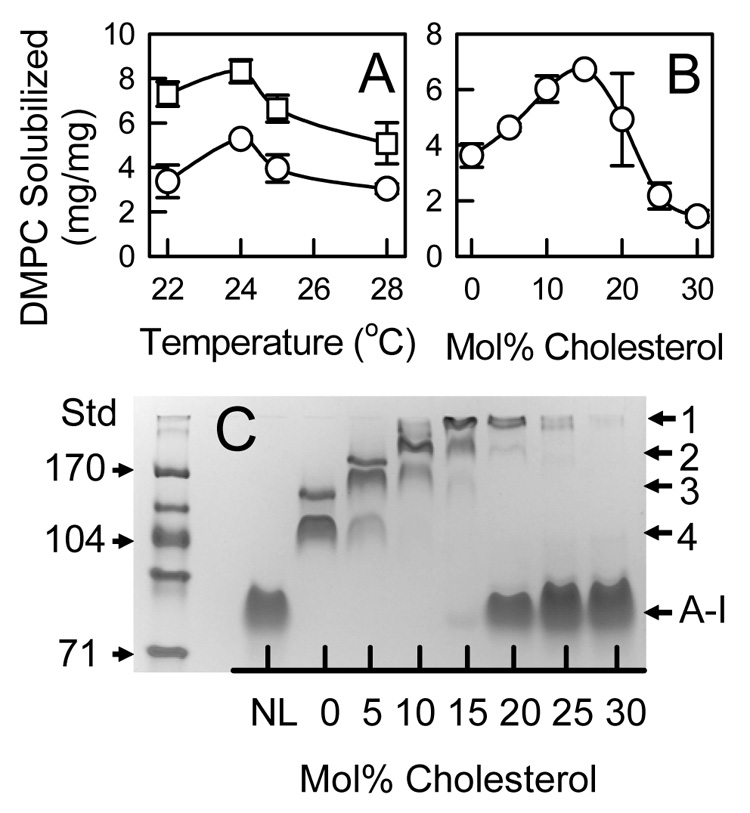

At a weight ratio of 2 mg DMPC/mg apoA-I (84/1 mol/mol), the presence of lipid-free apoA-I indicated the amount of lipid limited the amount of rHDL formed (Figure 1C). ApoA-I was incubated at weight ratios from 2 to 10 mg DMPC/mg apoA-I (84/1 to 420/1 mol/mol) with DMPC MLV containing 0 and 10 mol% cholesterol 20 hrs at 24.0 °C. The unreacted DMPC MLV was removed by centrifugation and the supernatants were analyzed to determine the amount of DMPC solubilized (i.e. converted from MLV to rHDL). At both 0 and 10 mol% cholesterol, there was a linear increase in the DMPC solubilized versus the amount added from 2 to 10 mg DMPC/mg apoA-I (84/1 to 420/1 mol/mol) (Data not shown). The amount of DMPC solubilized went from 2.12 ± 0.29 (89 ± 12) to 5.28 ± 0.23 (222 ± 10) mg DMPC/mg apoA-I (mol/mol) at 0 mol% cholesterol and from 2.01 ± 0.04 (84 ± 2) to 8.32 ± 0.51 (350 ± 22) mg DMPC/mg apoA-I (mol/mol) at 10 mol% cholesterol. At different temperatures, more phospholipid incorporates into rHDL at 10 mol% cholesterol than without sterol (Figure 2A). The effect of cholesterol concentration (0 to 30 mol%) on rHDL formation was determined at a weight ratio 10 mg DMPC/mg apoA-I (420/1 mol/mol). After 20 hr incubation at 25.0 °C, the amount of phospholipid solubilized increased with the cholesterol concentration up to 15 mol% above which the amount declined (Figure 2B). Native PAGE analysis of the supernatant fractions (Figure 2C) reveals five protein bands, which comprise lipid-free apoA-I and four rHDL bands. As the cholesterol content was increased, the rHDL particle size increased. However, mostly lipid-free apoA-I was found at 20 and higher mol% cholesterol. Similar results were found for incubations at 22.0, 24.0, and 28.0 °C (data not shown). DSC thermograms of binary mixtures of cholesterol and saturated phosphatidylcholines demonstrate sharp and broad heat capacity peaks [38, 39]. The sharp peak is due to the chain melting of pure phospholipid and disappears at ~20–25 mol% cholesterol. Depending on the model, the broad peak has been attributed to the formation of a single lo phase [40] or condensed complexes of cholesterol and phospholipid [41–43]. The increase in lipid-free apoA-I and decrease in rHDL formation occurs in the cholesterol concentration range where the thermal transition of the pure phospholipid phase disappears.

Figure 2.

Effect of Cholesterol in DMPC MLV on Solubilization by ApoA-I. A: DMPC solubilized (mg DMPC/mg apoA-I) for MLV containing 0 (○) and 10 (□) mol% cholesterol determined as a function of temperature. The initial weight ratio was 10 mg DMPC/mg apoA-I (420/1 mol/mol). B: The amount of DMPC solubilized determined for MLV containing increasing amounts of cholesterol at 25.0 °C. C: Native PAGE analysis of rHDL formed as a function of cholesterol content at 25.0 °C. Five apoA-I containing protein bands were observed; four (numbered 1–4) were for rHDL and another was lipid-free apoA-I. Bands 1 and 2 migrated less than the 170 Å standard, band 3 was between the 122 and 170 Å standards, and band 4 co-migrated with the 104 Å protein standard.

3.3 Kinetics of Formation of Cholesterol-rich rHDL

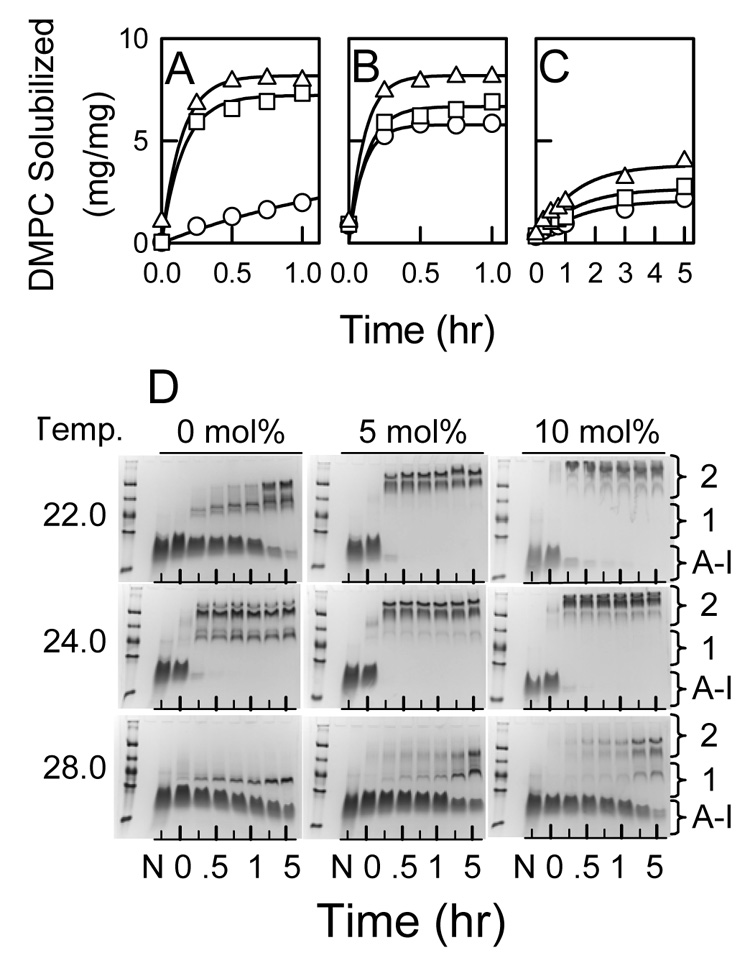

The kinetics of rHDL formation with DMPC MLV (10 mg DMPC/mg apoA-I, 420/1 mol/mol) containing 0, 5, and 10 mol% was measured at 22.0, 24.0, and 28.0 °C by the centrifugation assay (Figure 3). For DMPC MLV, the solubilization reaction was fastest and more DMPC was solubilized at 24.0 °C (Figure 3B). At 5 and 10 mol% cholesterol, the maximum amount of DMPC solubilized occurred after 30 min at 22.0 (Figure 3A) and 24.0 (Figure 3B) °C and was slower at 28.0 °C (Figure 3C). Native PAGE analysis demonstrates that different sized rHDL particles were formed at different concentrations of cholesterol and at different temperatures. This analysis also (Figure 3D) reveals a similar kinetic profile: at 0 mol% cholesterol rHDL formation is complete at 30 min at 24.0 °C and slower at the other two temperatures; rHDL formation is complete at 30 min or less for 5 and 10 mol% cholesterol at 22.0 and 24.0 °C; and rHDL formation for 5 and 10 mol% cholesterol was slower at 28.0 °C. At each temperature, the size of rHDL increased with the amount of cholesterol within MLV. Finally, rHDL formation does not indicate a precursor (small rHDL, band 1) to product (large rHDL, band 2) relationship. This is clearly seen at 28.0 °C, where the intensities of all protein bands at 0, 5, and 10 mol% cholesterol increase with time. Thus, different sized rHDL are formed concurrently and independently of each other.

Figure 3.

Temperature Dependence of the Kinetics of DMPC/Cholesterol MLV Solubilization by ApoA-I. The time dependence of DMPC solubilized (mg DMPC/mg apoA-I) by apoA-I for MLV containing 0 (○), 5 (□), and 10 (△) mol% cholesterol measured at 22.0 (A), 24.0 (B), and 28.0 (C) °C. The initial weight ratio was 10 mg DMPC/mg apoA-I (420/1 mol/mol). D: The time dependence of rHDL formation was determined by native PAGE analysis. The reaction temperatures and cholesterol contents of DMPC MLV are labeled; N = lipid-free apoA-I ran as a standard. The incubation times were 0, 0.25, 0.5, 0.75, 1, 3, and 5 hrs. Protein bands are indicated for lipid-free apoA-I, rHDL 1, which included bands that migrated between the 82 and 122 Å protein standards, and rHDL 2, which included bands that migrated less than the 122 Å standard (i.e. diameters > 122 Å).

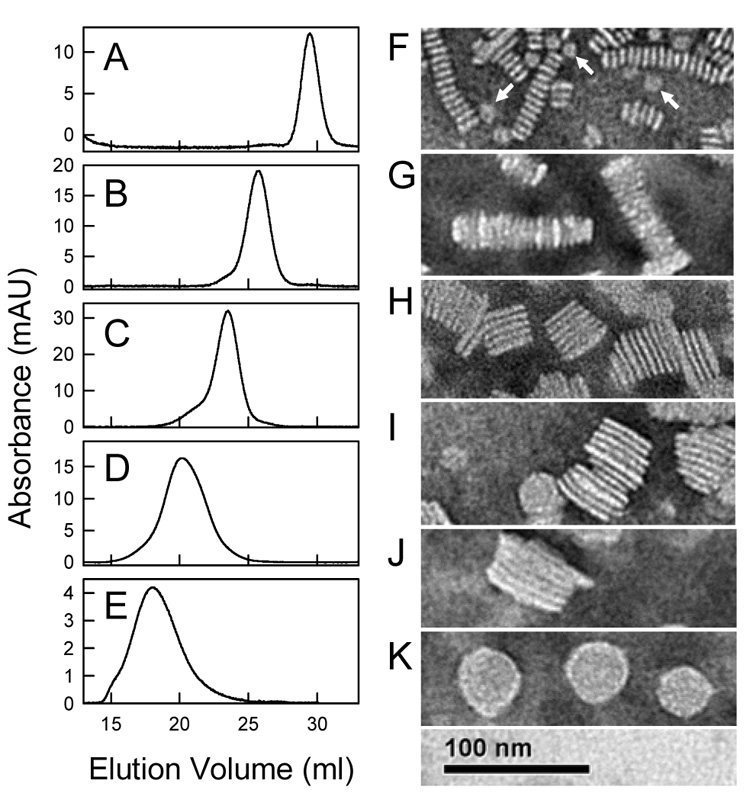

3.4 Isolation and Characterization of Cholesterol-rich rHDL

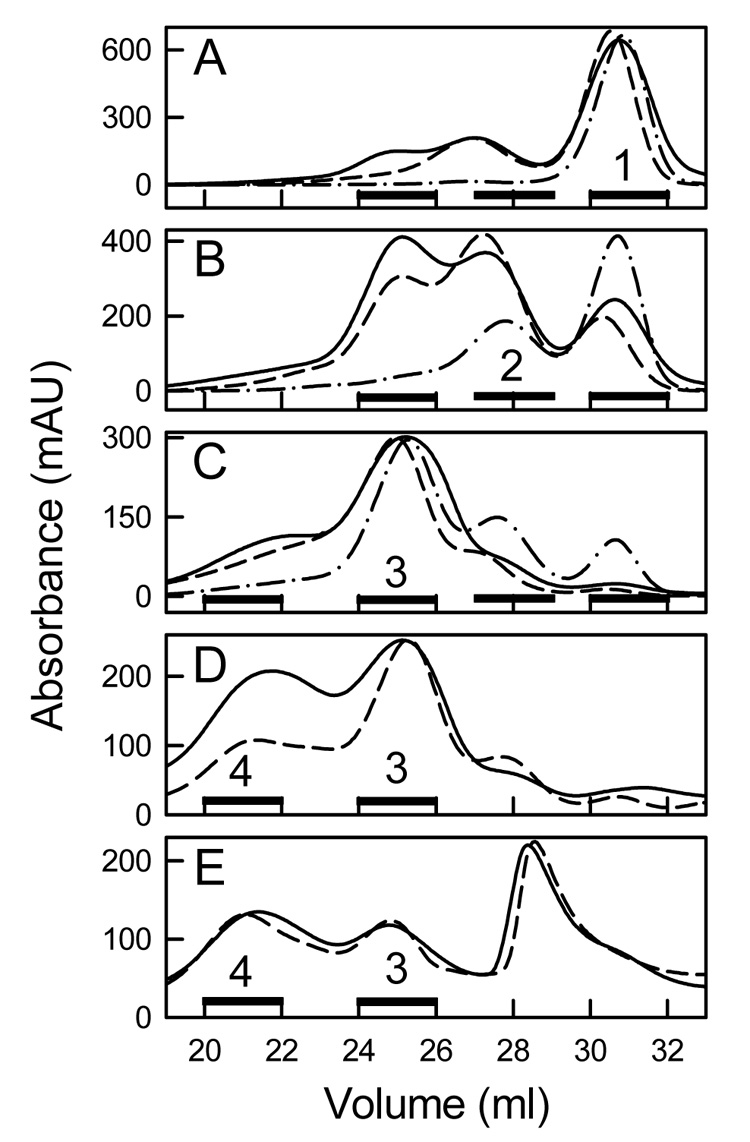

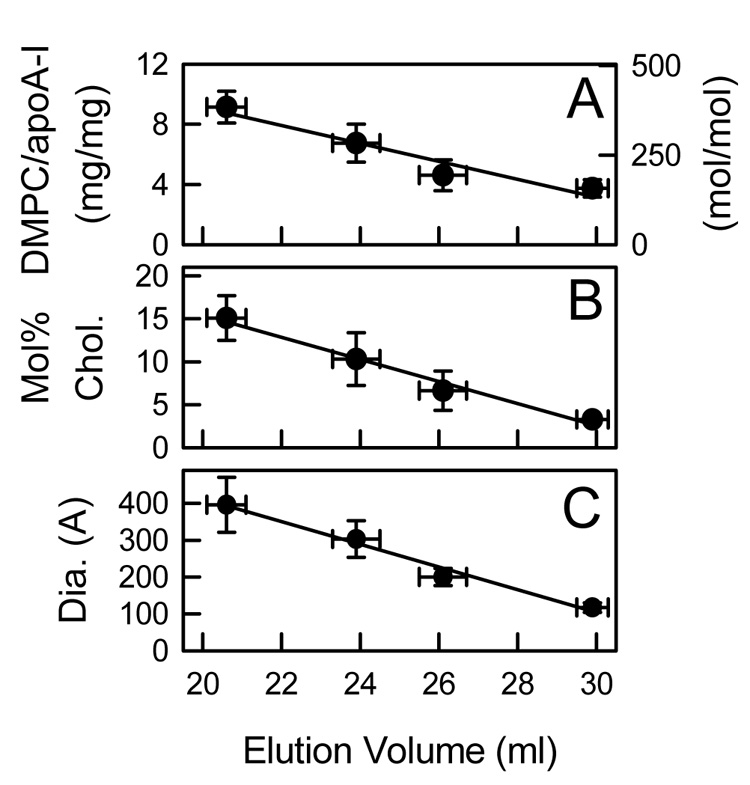

rHDL were formed at 24.0, 25.0, or 28.0 °C by mixing apoA-I with DMPC MLV (10 mg DMPC/mg apoA-I, 420/1 mol/mol) containing 0, 5, 10, 15, and 20 mol% cholesterol. The DMPC/apoA-I mixtures were fractionated by Superose 6 size exclusion chromatography (Figure 4) to isolate individual rHDL fractions. Varying both the amount of cholesterol and incubation temperature resulted in the formation of multiple rHDL particles. For example, comparing the elution profiles for 0 (Figure 4A) and 5 (Figure 4B) mol% cholesterol at all three incubation temperatures demonstrates that a greater amount of apoA-I eluted earlier for 5 mol% cholesterol MLV. This indicated the formation of a greater amount of larger sized rHDL particles. Also, the elution profiles indicate that the amount of larger sized rHDL particles was dependent upon the incubation temperature. In Figure 4B, there is clearly a greater amount of larger sized rHDL that elute earlier formed at 24.0 than at 28.0 °C. The elution profiles of the rHDL were distinguished by quantized jumps in the elution volume that correlated with the number of apoA-I molecules per rHDL particle; this was observed irrespective of sterol content and incubation temperature. For samples made with 0 to 15 mol% cholesterol (Figure 4 A–D), there was essentially no lipid-free apoA-I. At 20 mol% cholesterol, a new peak (elution volume peaked at ~ 29 ml) that represented self-associated apoA-I was seen (Figure 4E). Differently sized rHDL particles (numbered rHDL Fractions 1–4) were pooled for further analysis. For the EM studies, a fifth fraction was analyzed that eluted as a shoulder between 16–19 ml. Pooled fractions were rechromatographed to confirm their homogeneity (Figure 5 A–E) and observed by negative staining electron microcopy (Figure 5 F–K). All of the rHDL Fractions appeared as the well known rouleaux structures that characterize small discoidal rHDL with a bilayer width of ~ 48 Å. The en face views of small rHDL (Fraction 1) and large rHDL (Fraction 4) are shown (Figure 5 F and K, respectively). The average diameter of rHDL Fractions 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 are 117 ± 13, 200 ± 23, 303 ± 50, 396 ± 75, and 473 ± 68 Å, respectively (Figure 6C, Table 1). According to the double belt model, where two paired apoA-I molecules circumscribe the perimeter of the particle in an extended α-helical conformation, the calculated circumferences correspond to particles with 2.3, 4.1, 6.3, 8.3, and 9.9 apoA-I molecules per rHDL particle (Table 1). The DMPC/apoA-I stoichiometry (mg DMPC/mg apoA-I, mol/mol) (Figure 6A), the mol% cholesterol in rHDL (Figure 6B), and the diameter of rHDL (Figure 6C) are proportional to the rHDL elution volumes.

Figure 4.

Separation of rHDL by Size Exclusion Chromatography. rHDL were formed by incubating apoA-I and DMPC/cholesterol MLV (10 mg DMPC/mg apoA-I, 420/1 mol/mol) at 24.0 (solid line), 25.0 (dash line), and 28.0 (dash dot line) °C. The elution profiles are for DMPC/cholesterol MLV that contained 0 (A), 5 (B), 10 (C), 15 (D), and 20 (E) mol% cholesterol. Black bars represent the fractions (Fractions 1 to 4) that were pooled for analysis. For comparison, human LDL, HDL3, and monomeric lipid-free apoA-I elute at 23, 31.2, and 35 ml, respectively.

Figure 5.

Analysis of rHDL Fractions by Negative Staining Electron Microscopy. The isolated rHDL Fractions were characterized by a second analytical Superose 6 chromatography run (Panels A–E) and by negative staining electron microscopy (Panels F–K). The rHDL were formed at 24.0 °C from DMPC MLV containing various mol% cholesterol; A, F: Fraction 1, 0 mol% cholesterol; B, G: Fraction 2, 0 mol%; C, H: Fraction 3, 10 mol%; D, I, and K: Fraction 4, 15 mol%; E, J: Fraction 5 (the shoulder between 16 and 19 ml of Figure 4D), 15 mol%. Each Fraction exhibited the rouleaux appearance that characterizes discoidal rHDL. En face orientations of small rHDL Fraction 1 (F, white arrows) and large rHDL Fraction 4 (K) are shown.

Figure 6.

Analysis of rHDL Fractions. Pooled rHDL fractions were chemically analyzed for weight (mg/mg) and molar (mol/mol) stoichiometry of DMPC/apoA-I (A) and mol% cholesterol in rHDL (B) and for particle size (diameter in Å) by negative staining electron microscopy (C) and plotted as a function of their peak elution volume observed by analytical Superose 6 chromatography. The lipid composition (A, B) of 28 pooled rHDL Fractions were determined.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Cholesterol–rich rHDL Particles

| rHDL | Diameter (Å)a | apoA-I/rHDL (mol/particle)b | apoA-I/rHDL (mol/particle)c | DMPC/apoA-I (mol/mol)d | DMPC/rHDL (mol/particle)e | DMPC/apoA-I (mol/mol)f |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 117 ± 13 | 2.3 | 1.8 | 148 ± 13 | 210 | 105 |

| 2 | 200 ± 23 | 4.1 | 3.8 | 192 ± 42 | 730 | 183 |

| 3 | 303 ± 50 | 6.3 | 5.3 | 261 ± 44 | 1800 | 300 |

| 4 | 396 ± 75 | 8.3 | 7.8 | 378 ± 45 | 3170 | 396 |

| 5 | 473 ± 68 | 9.9 | n.d. | n.d. | 4600 | 460 |

Particle diameter was determined by negative staining electron microscopy (Figure 5).

The number of apoA-I molecules per rHDL particle were calculated from the circumference as determined from the mean EM diameter (d in Å) assuming a double belt model and that the protein was 80% α-helical. The length (l) of apoA-I on the edge of a discoidal rHDL particle was estimated to be 292 Å per apoA-I molecule. This was calculated from (l = 243 AA residues/apoA-I molecule × 0.80 α-helical residues/AA residues × 1.5 Å /α-helical residue). The number of apoA-I/rHDL = 2π (d-10)/ (292 Å/apoA-I molecule) which is calculated at the center of the α-helical segments using an α helix center to edge distance of 5 Å [14].

The number of apoA-I molecules per rHDL particle was determined by chemical cross-linking using BS3 as indicated in Figure 7. (The n.d. stands for not determined).

The lipid/protein stoichiometry of moles DMPC/moles apoA-I for each rHDL particle was determined by chemical analysis as indicated in Figure 6.

The estimated stoichiometry of number of DMPC molecules per rHDL particle was calculated as number of DMPC per rHDL = 2π[(d-20)/2]2/70 assuming a helix diameter of 10 Å and a surface area/DMPC of 70 Å2 [37].

The estimated stoichiometry of moles DMPC/moles apoA-I was calculated from the estimated number of DMPC molecules per rHDL particle assuming that rHDL fractions 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 had 2, 4, 6, 8, and 10 molecules of apoA-I per rHDL particle, respectively.

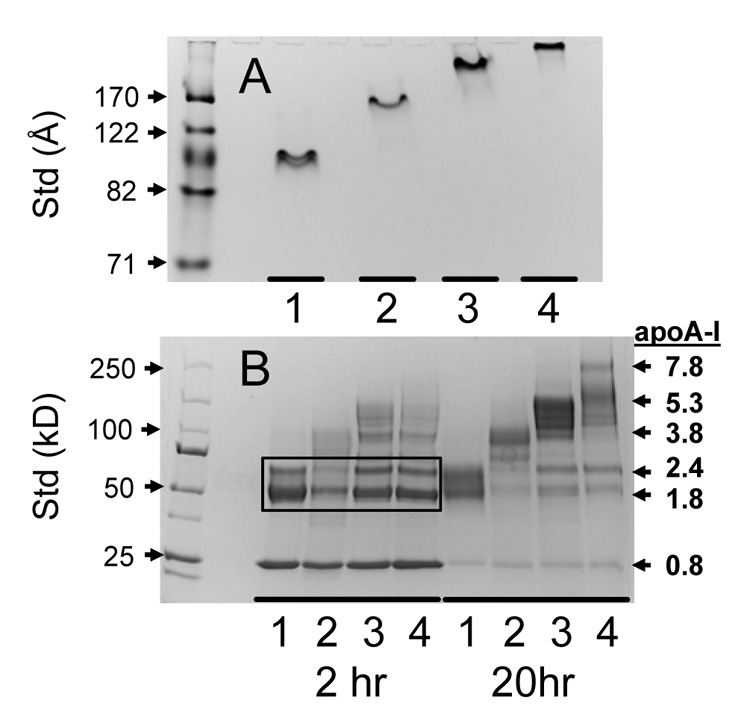

To experimentally verify the number of apoA-I molecules per rHDL, rHDL were also chemically cross-linked with BS3. rHDL Fractions isolated from incubating apoA-I with DMPC/sterol MLV at 0 mol% (Fractions 1 and 2), 10 mol% cholesterol (Fraction 3), and 15 mol% cholesterol (Fraction 4) at 24 °C were used and were homogeneous according to native PAGE analysis (Figure 7A). rHDL were incubated at a molar ratio of 10/1 BS3/apoA-I for 2 and 20 hr at room temperature (Figure 7B). Based on analysis of the molecular weight standards, the pooled rHDL Fractions 1, 2, 3, and 4 had 1.8, 3.8, 5.3, and 7.8 molecules of apoA-I/rHDL. For the 2 hr incubation, Fractions 1, 2, 3, and 4 had the same pattern of major bands (box in Figure 7B) which suggests that they contain the same basic structural unit of paired apoA-I molecules that surround the perimeter of the particle. Chemically cross-linked proteins can migrate anomalously on SDS PAGE gels because they are not always completely unfolded. The two major bands indicated as containing 1.8 and 2.4 molecules of apoA-I per rHDL probably represent cross-linked dimers where the cross-links are in different regions of the apoA-I molecule [24]. The number of apoA-I molecules per rHDL particles estimated from the diameter determined by EM and by chemical cross-linking (Table 1) are in good agreements and indicate that rHDL Fractions 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 contain 2, 4, 6, 8, and 10 molecules of apoA-I per rHDL particle. The number of DMPC molecules per rHDL particle can be estimated from the measured diameter and the molar stoichiometry of DMPC/apoA-I can then be estimated assuming the number of apoA-I molecules per rHDL particle (Table 1). Based on these calculations, the estimated stoichiometry and the chemically determined stoichiometry are in good agreement (Table 1). Additionally, the calculated values of DMPC/rHDL (mol/particle) (Table 1) demonstrate that one large particle (Fraction 4) containing 8 molecules of apoA-I solubilizes at least three times more phospholipid than four small particles (Fraction 1) that utilize the same number of molecules of apoA-I.

Figure 7.

Assessment of rHDL Homogeneity and apoA-I/Particle Stoichiometry. Representative rHDL Fractions 1–4 were analyzed by native PAGE to demonstrate homogeneity (A) and were chemically cross-linking with BS3 for 2 and 20 hr. and analyzed by SDS PAGE to determine the number of apoA-I molecules per rHDL particle (B). The rHDL Fractions 1, 2, 3, and 4 were from incubations at 24.0 °C for DMPC MLV containing 0, 5, 10, and 15 mol% cholesterol, respectively. At 2 hr, the different sized rHDL Fractions have the same cross-linking pattern (black box). At 20 hr, larger molecular weight bands are seen. The number of apoA-I molecules per particle was estimated by comparison with molecular weight standards (Panel B, right axis).

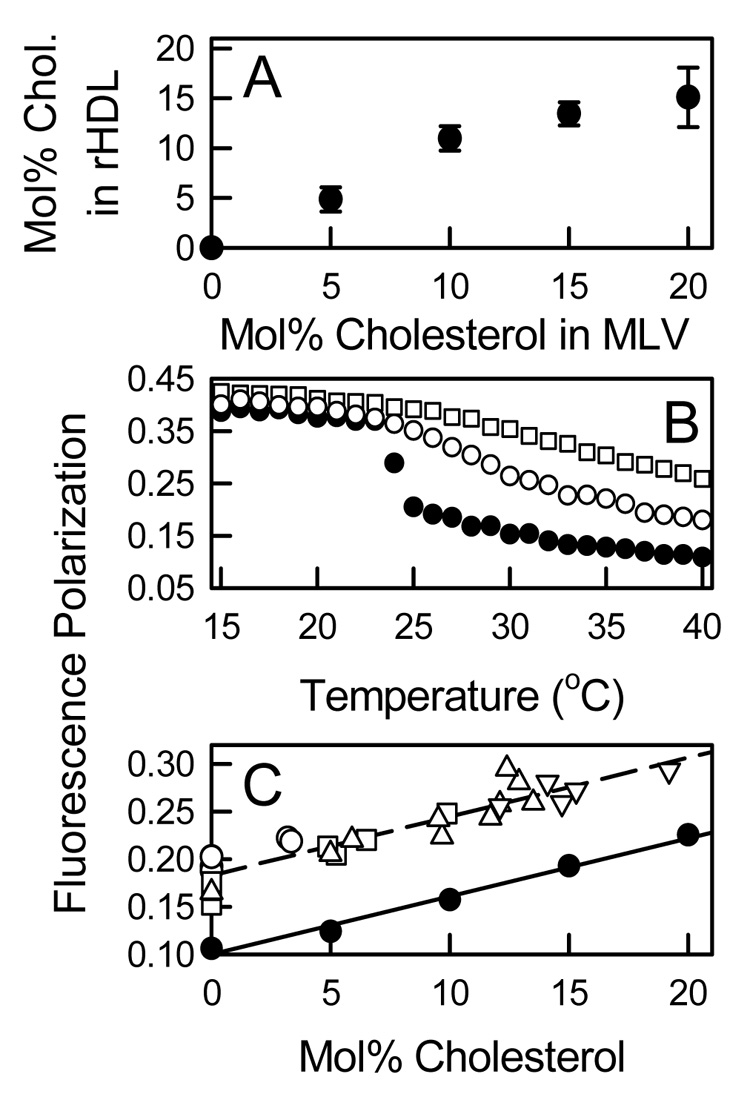

The mol% cholesterol in isolated rHDL was proportional to the mol% cholesterol in the original DMPC/sterol MLV (Figure 8A). Analysis of the thermal properties of rHDL with and without cholesterol by DPH fluorescence polarization indicate that rHDL formation broadened the phase transition of DMPC when compared to MLV and in the presence of cholesterol eliminated the transition (Figure 8B). At 37 °C, DPH polarization values where higher in rHDL than in MLV however the change in polarization with mol% cholesterol was identical for rHDL and MLV (Figure 8C). These polarization results are consistent with previous models that indicate two different bilayer environments for DMPC [44–46]. These are a boundary phospholipid bilayer (estimated to be the width of two phospholipid molecules) [46] that excludes cholesterol and whose dynamic motions are perturbed because they are adjacent to the protein [45] and a bulk lipid fraction that has similar motional properties of DMPC/cholesterol in MLV. The observed polarization is simply the sum of the properties of the two different environments.

Figure 8.

Compositions and Lipid Dynamics of rHDL. A: Correlation between rHDL cholesterol content with the cholesterol content of the DMPC MLV from which it was derived. B: Thermal behavior of DMPC MLV (●) and rHDL Fraction 1 with no cholesterol (○) and rHDL Fraction 4 with 15 mol% cholesterol (□) as assessed by the temperature dependence of the fluorescence polarization of DPH. C: The fluorescence polarization of DPH at 37 °C for individual rHDL Fractions 1 (○), 2 (□), 3 (△), and 4 (▽) and for DMPC MLV (●) as a function of the mol% cholesterol.

4. Discussion

Recent studies have demonstrated that the activity of ABCA1 creates two types of high affinity binding sites for apoA-I on the cell surface [3, 12, 13]. At a low capacity site there is direct protein-protein interactions between apoA-I and ABCA1 which has been proposed to serve a regulatory function. A higher capacity site involves lipid-protein interactions between apoA-I and the plasma membrane and functions in the lipidation of apoA-I to form nascent HDL. This site is proposed to be created by the lipid floppase activity of ABCA1 to pump phospholipids from the cytoplasmic leaflet to the exofacial leaflet of the bilayer and forms strained lipid domains with positive membrane curvature (membrane buds out). The lipid nature of this site was indicated when phosphatidylcholine-specific phospholipase C, but not sphingomyelinase, treatment of cells inhibited apoA-I binding, cholesterol efflux, and nascent HDL formation [12]. Similarly, changing the membrane sterol composition by incorporation of 7-ketocholesterol or rapid exposure to cyclodextrins to remove cholesterol also inhibit apoA-I binding and apoA-I mediated cholesterol efflux [47]. At this site, apoA-I simultaneously removes phospholipid and cholesterol in whatever proportions they are present to microsolubilize a lipid domain to form a nascent HDL particle. The mechanism of membrane microsolubilization is proposed to be the same as that for apoA-I mediated solubilization of DMPC bilayers [3]. Our results suggest that the cholesterol composition of lipid domains created by ABCA1 would facilitate the membrane association of apoA-I and the speciation of the nascent HDL particles formed.

ApoA-I and other native and mutant apolipoproteins spontaneously solubilizes MLV and LUV of DMPC to form discoidal rHDL [15–20]. This process is not unique to DMPC, since apoA-I can also spontaneously solubilize bilayers of sphingomyelin [21], binary mixtures of saturated phosphatidylcholines [22], and phospholipid and cholesterol mixtures that represent the composition of isolated nascent HDL [3]. However, for apoA-I to form rHDL with phospholipids that possess longer or more unsaturated acyl chains requires the cholate dialysis method [31, 32]. The kinetics of DMPC solubilization can be measured in real time using spectroscopic measurements of changes in turbidity and is a commonly used method to measure the lipid binding activities of apolipoproteins. In general, the ratio of the reactants using MLV (2 mg DMPC/mg apoA-I, 84/1 mol/mol) [29, 30] or LUV (100 mol DMPC/mol apoA-I) [24] is chosen to form homogeneous rHDL particles and to have complete clearance of turbidity. In this study, the rate of solubilization of DMPC MLV is maximum at Tm with a t1/2 of ~ 4 min and is ~ 90 fold slower a few degrees below and above Tm. However, identically sized rHDL particles are formed below, at, and above Tm. Increasing the bilayer cholesterol concentration enhanced the rate of solubilization and resulted in the formation of larger sized rHDL. These rHDL particles had diameters of 97, 130, and 170 Å and are identical in size to particles made from DPPC and cholesterol [31] and POPC and cholesterol [32] by cholate dialysis that contain 2, 3, and 4 molecules of apoA-I. By varying the temperature and sterol concentration, the rates of solubilization varied almost 3 orders of magnitude; however, the sizes of the rHDL formed were independent of the rate of their formation and dependent upon the bilayer cholesterol concentration. A molecular basis for the formation of a sterol-rich ordered lipid phase is that cholesterol forms stoichiometic chemical complexes with specific phospholipids, e.g. saturated phosphatidylcholines, such that this chemical interaction depends upon sterol structure [41–43]. We previously demonstrated that different oxysterols, e.g. 7-ketocholesterol, which are less efficient in forming ordered lipid phases than cholesterol are 2 to 35 fold less effective than cholesterol in enhancing the rate [29, 30]. However, lathosterol and β-sitosterol which are measurably better than cholesterol in forming ordered lipid phases did not significantly enhance the rate [48, 49]. The rate limiting step in rHDL formation is the insertion α-helical segments of apoA-I into lattice defects that occur at so and ld phase boundaries. Cholesterol and other sterols affect the rate of solubilization by their ability to form a sterol-rich phase or phospholipid-sterol complexes to generate more phase boundaries and more defects as sites for protein insertion. Thus, the rate of formation of rHDL by membrane solubilization is controlled by factors that affect the microheterogeneity, e.g. number or size of defects, at the bilayer surface. However, the intrinsic structural properties of apoA-I to form a three dimensional lipid-protein complex which involves protein-protein interactions between multiple molecules of apoA-I, lipid-protein interactions between apoA-I and phospholipids, and lipid-lipid interactions between phospholipids and cholesterol determines the particle size. This is evidenced by the fact that identical particles are formed by totally different physical methods, i.e. membrane solubilization and cholate dialysis.

In the membrane solubilization process at 10 mg DMPC/mg apoA-I (420/1 mol/mol), the amount of cholesterol in DMPC MLV was the major determinant of rHDL size, lipid composition, and number of apoA-I molecules. However, there was temperature dependence with smaller particles being formed at 28.0 versus 22.0 and 24.0 °C. The major rHDL particles that were isolated and characterized varied in size from ~ 120 to 400 Å, contained 2 to 8 apoA-I molecules per particle, and had a similar cholesterol content to the reactant DMPC MLV (Figure 6 and 8). The even number of apoA-1 molecules point toward multiple copies of dimeric apoA-I in a double belt orientation and suggest that this is the most thermodynamically stable and preferred structure for apoA-I in discoidal rHDL [14, 23, 24, 27]. One consequence of the formation of larger particles is that it enables apoA-I to be more efficient in solubilizing lipid. In the most extreme case, the composition of a particle which contained 8 molecules of apoA-I contained approximately 3000 molecules of DMPC and 500 molecules of cholesterol, whereas 4 particles containing 2 molecules of apoA-I would solubilize approximately 1200 molecules of DMPC and 50 molecules of cholesterol (Table 1). Large nascent HDL have been previously identified by incubating apoA-I with macrophages and cells stably expressing ABCA1. These particles have varied in size (diameters from ~ 90–200 Å) and number of apoA-I molecules (from 2 to 8 molecules) [25, 26, 33, 34]. Similarly, we have observed that larger nascent HDL particles are isolated after incubating apoA-I with THP-1 macrophages that have been cholesterol loaded with acetylated LDL than from cells where ABCA1 was pharmacologically up-regulated (Massey and Pownall, unpublished results). Cholesterol-loading with acetylated LDL is known to increase the amount of cholesterol in the plasma membrane [54, 55]. Different sized nascent HDL have been proposed to be formed independently from ABCA1 located in different membrane environments. It seems highly likely that the major factor that contributes to these different membrane environments is their cholesterol content and probably specific phospholipid species which have an affinity for cholesterol.

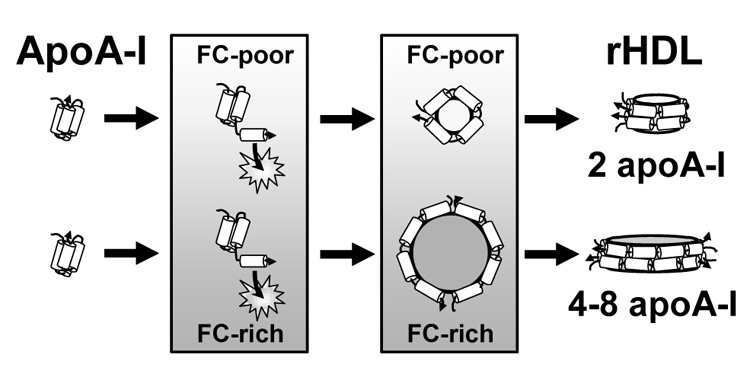

We propose a model for the apoA-I mediated solubilization of DMPC/cholesterol MLV that leads to the speciation of rHDL particles (Figure 9). In DMPC/cholesterol bilayers above Tm, conditions which emulates cell membranes, there are two different models by which 0–25 mol% cholesterol determines the biophysical properties of saturated phosphatidylcholines. In one model, there is liquid-liquid phase separation into phospholipid-rich ld and cholesterol-rich lo domains (size ~ 20–80 nm) where the lo domains increase in size with the cholesterol concentration [40]. In the second model, cholesterol forms stoichiometric condensed complexes with phospholipid, where the phospholipid-cholesterol mixtures are monophasic and the bilayer properties continuously change as a function of cholesterol concentration [41–43]. We observed a direct correlation between the mol% cholesterol in isolated rHDL and the mol% cholesterol in the original phospholipid mixture (Figure 8A). This relationship would not hold if apoA-I separately solubilized phospholipid-rich ld or cholesterol-rich lo domains since this would result in rHDL with different amounts of cholesterol. Our data indicates that apoA-I solubilizes a more homogeneous bilayer which is consistent with the formation of condensed cholesterol/phospholipid complexes whose stoichiometry increases with the cholesterol concentration. However, in the ternary system of phosphatidylcholine/sphingomyelin/cholesterol, where lateral fluid-fluid phase separation into phospholipid-rich ld and sphingomyelin/cholesterol-rich lo domains has been demonstrated, apoA-I preferentially solubilizes cholesterol-poor ld domains [21, 52]. In our model (Step 1), the hydrophobic C-terminal α-helices of apoA-I insert into lattice defects in the membrane surface which occurs when DMPC bilayers undergo a thermal phase transition (Figure 9). This is the rate limiting step in rHDL formation. ApoA-I also spontaneously inserts into highly curved but not planar bilayers [3]. In Step 2, apoA-I penetrates into the bilayer, unfolds, and forms “double belt dimers” that build a protein scaffold to solubilize a cargo of phospholipid and cholesterol. In our system, rHDL with three apoA-I molecules is formed only when the amount of lipid is limiting (Figure 1C). The odd apoA-I molecule is presumably in a hairpin turn (Figure 1) [2]. The number of apoA-I molecules utilized is dependent upon the bilayer cholesterol concentration which suggests that both phospholipid molecules and phospholipid/cholesterol complexes are used as lipid cargo. Some of the phospholipid molecules are used to form a boundary lipid layer. Finally, protein/lipid complexes dissociate from the membrane to form discoidal rHDL particles (Step 3) [18]. Thus, the rate of formation, lipid composition, and three-dimensional structures of cholesterol-rich rHDL are dictated primarily by the original membrane phase properties and cholesterol content.

Figure 9.

Model for rHDL Formation from DMPC/Cholesterol MLV. ApoA-I solubilization of DMPC MLV to form rHDL comprises three Steps. In Step 1, C-terminal α-helical segments of apoA-I insert into lattice defects (indicated by stars) in the membrane surface created by the so to ld thermal transition; this is the rate limiting step in rHDL formation. In the plane of the bilayer, cholesterol (FC) and DMPC form condensed complexes which demonstrate monophasic behavior where the bilayer properties continuously change as a function of the cholesterol (FC-poor → FC-rich) concentration. At any temperature and cholesterol concentration, the bilayer is homogeneous with no lateral separation into domains of different composition and biophysical properties [42, 43]. In Step 2, apoA-I molecules unfold from their lipid-free structure and form a protein scaffold based on two apoA-I molecules in a double belt orientation (“double belt dimers”) to locally solubilize a volume of the adjacent lipid bilayer. The volume of bilayer solubilized is dependent upon the cholesterol concentration (formation of phospholipid/cholesterol complexes), such that more “double belt dimers” are used to solubilize FC-rich vs. FC-poor membranes. Some phospholipid molecules form a boundary layer where cholesterol is excluded. In Step 3, protein/lipid complexes dissociate from the membrane to form discoidal rHDL particles whose size, lipid composition, lipid/protein stoichiometry, and number of apolipoproteins per particle are dependent on the original membrane biophysical properties and cholesterol concentration.

The intrinsic structural properties of apoA-I to interact with phospholipids and form a bilayer disk must be the basis for similar discoidal HDL particles being formed by cholate dialysis, membrane solubilization, and by the activity of ABCA1. Additionally, there is a similar affect of the addition of cholesterol on the size, lipid composition, and number of apoA-I molecules in discoidal rHDL formed by cholate dialysis and membrane solubilization. By simply changing the temperature, the rate for apoA-I mediated solubilization of DMPC MLV can be varied from a few minutes to several hours; however, it does not change the structure of the rHDL particle formed. Based on the lipid composition of isolated nascent HDL, apoA-I can also solubilize MLV containing physiological relevant mixtures of phospholipid and cholesterol within the time scale of hours [3]. The mechanism described above proposes that ABCA1 creates a membrane environment where apoA-I can overcome the initial kinetic barrier of protein-membrane association and spontaneously microsolubilize a membrane domain in the same manner that it spontaneously solubilizes DMPC MLV. Our results indicate that the size speciation of discoidal rHDL and probably nascent HDL is mechanistically linked to the cholesterol content of the membranes from which they were formed. For nascent HDL, the cholesterol content may also be regulated by a unique membrane phospholipid composition [53]. One consequence the particle speciation of nascent HDL based on the structural and compositional properties of size, cholesterol content, and number of apoA-I molecules is that they also should greatly vary in their metabolic properties as LCAT substrates [31] and as donor and acceptor particles in cholesterol transfer [32, 54].

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (HL-30914 and HL-56865 to HJP).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Abbreviations: ABCA1, ATP binding cassette transporter A1; apoA-I, apolipoprotein A-I; DMPC, dimyristoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine; DPH, 1,6-diphenyl-1,3,5-hexatriene; DPPC, dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine; DSC, differential scanning calorimetry; EM, transmission electron microscopy; HDL, high density lipoproteins; ld, liquid-disordered phase; lo, liquid-ordered phase; LUV, large unilamellar vesicles; MLV, multilamellar vesicles; mol/mol, molar ratio of DMPC/apoA-I; PAGE, polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis; POPC, 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine; rHDL, reassembled discoidal HDL; RCT, reverse cholesterol transport; so, solid-ordered or gel phase; SM, sphingomyelin; Tm, midpoint temperature of the gel to ld phase transition.

Contributor Information

John B. Massey, Department of Medicine, Baylor College of Medicine, One Baylor Plaza, Houston, Texas 77030.

Henry J. Pownall, Section of Atherosclerosis and Vascular Medicine, Department of Medicine, Baylor College of Medicine, One Baylor Plaza, Houston, Texas 77030

References

- 1.Curtiss LK, Valenta DT, Hime NJ, NJ, Rye KA. What is so special about apolipoprotein AI in reverse cholesterol transport? Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2006;26:12–19. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000194291.94269.5a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Davidson WS, Thompson TB. The structure of apolipoprotein A-I in high density lipoproteins. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:22249–22253. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R700014200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vedhachalam C, Duong PT, Nickel M, Nguyen D, Dhanasekaran P, Saito H, Rothblat GH, Lund-Katz S, Phillips MC. Mechanism of ATP-binding cassette transporter AI (ABCA1)-mediated cellular lipid efflux to apolipoprotein A-I and formation of high density lipoprotein particles. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:25123–25130. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704590200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Timmins JM, Lee JY, Boudyguina E, Kluckman KD, Brunham LR, Mulya A, Gebre AK, Coutinho JM, Colvin PL, Smith TL, Hayden MR, Maeda N, Parks JS. Targeted inactivation of hepatic Abca1 causes profound hypoalphalipoproteinemia and kidney hypercatabolism of apoA-I. J. Clin. Invest. 2005;115:1333–1342. doi: 10.1172/JCI23915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brunham LR, Kruit JK, Iqbal J, Fievet C, Timmins JM, Pape TD, Coburn BA, Bissada N, Staels B, Groen AK, Kuipers F, Hayden MR. Intestinal ABCA1 directly contributes to HDL biogenesis in vivo. J. Clin. Invest. 2006;116:1052–1062. doi: 10.1172/JCI27352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang X, Collins HL, Ranalletta M, Fuki IV, Billheimer JT, Rothblat GH, Tall AR, Rader DJ. Macrophage ABCA1 and ABCG1, but not SR-BI, promote macrophage reverse cholesterol transport in vivo. J. Clin. Invest. 2007;117:2216–2224. doi: 10.1172/JCI32057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Panagotopulos SE, Witting SR, Horace EM, Hui DY, Maiorano JN, Davidson WS. The role of apolipoprotein A-I helix 10 in apolipoprotein-mediated cholesterol efflux via the ATP-binding cassette transporter ABCA1. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:39477–39484. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207005200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Remaley AT, Thomas F, Stonik JA, Demosky SJ, Bark SE, Neufeld EB, Bocharov AV, Vishnyakova TG, Patterson AP, Eggerman TL, Santamarina-Fojo S, Brewer HB. Synthetic amphipathic helical peptides promote lipid efflux from cells by an ABCA1-dependent and an ABCA1-independent pathway. J. Lipid Res. 2003;44:828–836. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M200475-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vedhachalam C, Liu L, Nickel M, Dhanasekaran P, Anantharamaiah GM, Lund-Katz S, Rothblat GH, Phillips MC. Influence of ApoA-I structure on the ABCA1-mediated efflux of cellular lipids. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:49931–49939. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406924200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Natarajan P, Forte TM, Chu B, Phillips MC, Oram JF, Bielicki JK. Identification of an apolipoprotein A-I structural element that mediates cellular cholesterol efflux and stabilizes ATP binding cassette transporter A1. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:24044–24052. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400561200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fitzgerald ML, Morris AL, Chroni A, Mendez AJ, Zannis VI, Freeman MW. ABCA1 and amphipathic apolipoproteins form high-affinity molecular complexes required for cholesterol efflux. J. Lipid Res. 2004;45:287–294. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M300355-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hajj Hassan H, Denis M, Donna Lee DY, Iatan I, Nyholt D, Ruel I, Krimbou L, Genest J. Identification of an ABCA1-dependent phospholipid-rich plasma membrane apolipoprotein A-I binding site for nascent HDL formation: Implications for current models of HDL biogenesis. J. Lipid Res. 2007;48:2428–2442. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M700206-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vedhachalam C, Ghering AB, Davidson WS, Lund-Katz S, Rothblat GH, Phillips MC. ABCA1-induced cell surface binding sites for ApoA-I. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2007;27:1603–1609. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.145789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li L, Chen J, Mishra VK, Kurtz JA, Cao D, Klon AE, Harvey SC, Anantharamaiah GM, Segrest JP. Double belt structure of discoidal high density lipoproteins: molecular basis for size heterogeneity. J. Mol. Biol. 2004;343:1293–1311. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pownall HJ, Massey JB, Kusserow SK, Gotto AM., Jr. Kinetics of lipid-protein interactions: interaction of apolipoprotein A-I from human plasma high density lipoproteins with phosphatidylcholines. Biochemistry. 1978;17:1183–1188. doi: 10.1021/bi00600a008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pownall HJ, Pao Q, Hickson D, Sparrow JT, Kusserow SK, Massey JB. Kinetics and mechanism of association of human plasma apolipoproteins with dimyristoylphosphatidylcholine: effect of protein structure and lipid clusters on reaction rates. Biochemistry. 1981;20:6630–6635. doi: 10.1021/bi00526a017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhu K, Brubaker G, Smith JD. Large disk intermediate precedes formation of apolipoprotein A-I-dimyristoylphosphatidylcholine small disks. Biochemistry. 2007;46:6299–6307. doi: 10.1021/bi700079w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Segall Ml, Dhanasekaran P, Baldwin F, Anantharamaiah GM, Weisgraber KH, Phillips MC, Lund-Katz S. Influence of apoE domain structure and polymorphism on the kinetics of phospholipid vesicle solubilization. J. Lipid Res. 2002;43:1688–1700. doi: 10.1194/jlr.m200157-jlr200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pearson K, Tubb MR, Tanaka M, Zhang XQ, Tso P, Weinberg RB, Davidson WS. Specific sequences in the N and C termini of apolipoprotein A-IV modulate its conformation and lipid association. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:38576–38582. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M506802200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beckstead JA, Wong K, Gupta V, Wan CP, Cook VR, Weinberg RB, Weers PM, Ryan RO. The C terminus of apolipoprotein A-V modulates lipid-binding activity. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:15484–15489. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M611797200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fukuda M, Nakano M, Sriwongsitanont S, Ueno M, Kuroda Y, Handa T. Spontaneous reconstitution of discoidal HDL from sphingomyelin-containing model membranes by apolipoprotein A-I. J. Lipid Res. 2007;48:882–889. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M600495-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Swaney JB. Properties of lipid-apolipoprotein association products. Complexes of human apoAI and binary phospholipid mixtures. J. Biol. Chem. 1980;255:8798–8803. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Silva RA, Hilliard GM, Li L, Segrest JP, Davidson WS. A mass spectrometric determination of the conformation of dimeric apolipoprotein A-I in discoidal high density lipoproteins. Biochemistry. 2005;44:8600–8607. doi: 10.1021/bi050421z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bhat S, Sorci-Thomas MG, Alexander ET, Samuel MP, Thomas MJ. Intermolecular contact between globular N-terminal fold and C-terminal domain of ApoA-I stabilizes its lipid-bound conformation: studies employing chemical cross-linking and mass spectrometry. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:33015–33025. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M505081200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu L, Bortnick AE, Nickel M, Dhanasekaran P, Subbaiah PV, Lund-Katz S, Rothblat GH, Phillips MC. Effects of apolipoprotein A-I on ATP-binding cassette transporter A1-mediated efflux of macrophage phospholipid and cholesterol: formation of nascent high density lipoprotein particles. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:42976–42984. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308420200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Duong PT, Collins HL, Nickel M, Lund-Katz S, Rothblat GH, Phillips MC. Characterization of nascent HDL particles and microparticles formed by ABCA1-mediated efflux of cellular lipids to apoA-I. J. Lipid Res. 2006;47:832–843. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M500531-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wu Z, Wagner MA, Zheng L, Parks JS, Shy JM, 3rd, Smith JD, Gogonea V, Hazen SL. The refined structure of nascent HDL reveals a key functional domain for particle maturation and dysfunction. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2007;14:861–868. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pownall HJ, Massey JB, Kusserow SK, Gotto AM., Jr. Kinetics of lipid-protein interactions: effect of cholesterol on the association of human plasma high-density apolipoprotein A-I with L-α-dimyristoylphosphatidylcholine. Biochemistry. 1979;18:574–579. doi: 10.1021/bi00571a004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Massey JB, Pownall HJ. Role of oxysterol structure on the microdomain-induced microsolubilization of phospholipid membranes by apolipoprotein A-I. Biochemistry. 2005;44:14376–14384. doi: 10.1021/bi051169y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Massey JB, Pownall HJ. The polar nature of 7-ketocholesterol determines its location within membrane domains and the kinetics of membrane microsolubilization by apolipoprotein A-I. Biochemistry. 2005;44:10423–10433. doi: 10.1021/bi0506425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wald JH, Krul ES, Jonas A. Structure of apolipoprotein A-I in three homogeneous, reconstituted high density lipoprotein particles. J. Biol. Chem. 1990;265:20037–20043. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Meng QH, Sparks DL, Marcel YL. Effect of LpA-I composition and structure on cholesterol transfer between lipoproteins. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:4280–4287. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.9.4280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Denis M, Haidar B, Marcil M, Bouvier M, Krimbou L, Genest J. Characterization of oligomeric human ATP binding cassette transporter A1. Potential implications for determining the structure of nascent high density lipoprotein particles. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:41529–41536. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406881200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Krimbou L, Hajj Hassan H, Blain S, Rashid S, Denis M, Marcil M, Genest J. Biogenesis and speciation of nascent apoA-I-containing particles in various cell lines. J. Lipid Res. 2005;46:1668–1677. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M500038-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Massey JB, Pownall HJ. Interaction of alpha-tocopherol with model human high-density lipoproteins. Biophys. J. 1998;75:2923–2931. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(98)77734-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Massey JB, Gotto AM, Jr., Pownall HJ. H.J. Human plasma high density apolipoprotein A-I: effect of protein-protein interactions on the spontaneous formation of a lipid-protein recombinant. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1981;99:466–474. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(81)91768-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhu HL, Atkinson D. Conformation and lipid binding of the N-terminal (1-44) domain of human apolipoprotein A-I. Biochemistry. 2004;43:13156–13164. doi: 10.1021/bi0487894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mabrey S, Mateo PL, Sturtevant JM. High-sensitivity scanning calorimetric study of mixtures of cholesterol with dimyristoyl- and dipalmitoylphosphatidylcholines. Biochemistry. 1978;17:2464–2468. doi: 10.1021/bi00605a034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McMullen TP, Lewis RN, McElhaney RN. Differential scanning calorimetric study of the effect of cholesterol on the thermotropic phase behavior of a homologous series of linear saturated phosphatidylcholines. Biochemistry. 1993;32:516–522. doi: 10.1021/bi00053a016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vist MR, Davis JH. Phase equilibria of cholesterol/dipalmitoylphosphatidylcholine mixtures: 2H nuclear magnetic resonance and differential scanning calorimetry. Biochemistry. 1990;29:451–464. doi: 10.1021/bi00454a021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Anderson TG, McConnell HM. Condensed complexes and the calorimetry of cholesterol-phospholipid bilayers. Biophys. J. 2001;81:2774–2785. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)75920-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McConnell H, Radhakrishnan A. Theory of the deuterium NMR of sterol-phospholipid membranes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2006;103:1184–1189. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510514103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pandit SA, Khelashvili G, Jakobsson E, Grama A, Scott HL. Lateral organization in lipid-cholesterol mixed bilayers. Biophys. J. 2007;92:440–447. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.093864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tall AR, Lange Y. Interaction of cholesterol, phospholipid and apoprotein in high density lipoprotein recombinants. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1978;513:185–197. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(78)90172-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Massey JB, She HS, Gotto AM, Jr., Pownall HJ. Lateral distribution of phospholipid and cholesterol in apolipoprotein A-I recombinants. Biochemistry. 1985;24:7110–7116. doi: 10.1021/bi00346a014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Denisov IG, McLean MA, Shaw AW, Grinkova YV, Sligar SG. Thermotropic phase transition in soluble nanoscale lipid bilayers. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2005;109:15580–15588. doi: 10.1021/jp051385g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gaus K, Kritharides L, Schmitz G, Boettcher A, Drobnik W, Langmann T, Quinn CM, Death A, Dean TT, Jessup W. Apolipoprotein A-1 interaction with plasma membrane lipid rafts controls cholesterol export from macrophages. FASEB J. 2004;18:574–576. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-0486fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Xu X, Bittman R, Duportail G, Heissler D, Vilcheze C, London E. Effect of the structure of natural sterols and sphingolipids on the formation of ordered sphingolipid/sterol domains (rafts). Comparison of cholesterol to plant, fungal, and disease-associated sterols and comparison of sphingomyelin, cerebrosides, and ceramide. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:33540–33546. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104776200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang J, Megha, London E. Relationship between sterol/steroid structure and participation in ordered lipid domains (lipid rafts): implications for lipid raft structure and function. Biochemistry. 2004;43:1010–1018. doi: 10.1021/bi035696y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Qin C, Nagao T, Grosheva I, Maxfield FR, Pierini LM. Elevated plasma membrane cholesterol content alters macrophage signaling and function. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2006;26:372–378. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000197848.67999.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jiang D, Devadoss A, Palencsar MS, Fang D, White NM, Kelley TJ, Smith JD, Burgess JD. Direct Electrochemical Evaluation of Plasma Membrane Cholesterol in Live Mammalian Cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:11352–11353. doi: 10.1021/ja074373c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pokorny A, Yandek LE, Elegbede AI, Hinderliter A, Almeida PF. Temperature and composition dependence of the interaction of delta-lysin with ternary mixtures of sphingomyelin/cholesterol/POPC. Biophys. J. 2006;91:2184–2197. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.085027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schifferer R, Liebisch G, Bandulik S, Langmann T, Dada A, Schmitz G. ApoA-I induces a preferential efflux of monounsaturated phosphatidylcholine and medium chain sphingomyelin species from a cellular pool distinct from HDL(3) mediated phospholipid efflux. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2007;1771:853–863. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2007.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vaughan AM, Oram JF. ABCA1 and ABCG1 or ABCG4 act sequentially to remove cellular cholesterol and generate cholesterol-rich HDL. J. Lipid Res. 2006;47:2433–2443. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M600218-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]