Abstract

We report a method for creating stimuli-responsive biomaterials in which scanning nonlinear excitation is used to photocrosslink proteins at submicrometer 3D coordinates. Proteins with differing hydration properties can be combined to achieve tunable volume changes that are rapid and reversible in response to changes in chemical environment. Protein matrices having arbitrary 3D topographies and definable density gradients over micrometer dimensions provide the ability to effect rapid (<1 sec) and precise mechanical manipulations by means of changes in hydrogel size and shape, and applicability of these materials to cell biology is shown through the fabrication of responsive bacterial cages.

Keywords: Escherichia coli, multiphoton lithography, nanobiotechnology, protein hydrogels, smart materials

The design of materials and devices that rely on the autonomous transduction of environmental signals is an area of intense interest in materials science and molecular engineering (1–6). Development of strategies that allow free-form fabrication of “smart” materials with three-dimensional (3D) micro- to nanoscale resolution will extend the utility of these materials across a broader range of applications. For instance, the ability to rapidly and precisely manipulate microscale objects has important applications in numerous fields of applied science and engineering, motivating development of techniques for transporting particles based on mechanical, fluidic, and optical mechanisms (7–10). Stimuli-responsive hydrogels, which can cycle between expanded and condensed states in response to environmental triggers (e.g., pH, ionic strength), could provide an alternative means to control precise microscopic motions, potentially through the action of multiple, independent components functioning in concert. Indeed, hydrogels have been successfully used as actuating mechanisms in microfluidic devices, functioning as stimuli-responsive valves (11, 12), pumps (13), clutches (14), and optics (15). The possibility for exploiting hydrogel components in integrated microscale devices has fueled interest in the development of materials that confer greater control over stimuli-response characteristics as well as materials-fabrication strategies that provide high-resolution topographic control of hydrogel features. Strategies have been explored to fabricate responsive hydrogels with micro- to nanoscale resolution by using, for instance, photon and electron beam lithography (16, 17), but these methods do not enable structural features to be defined arbitrarily in three dimensions. Alternatively, multiphoton fabrication, a technique that localizes photochemical reactions in three dimensions based on nonlinear absorption by photoinitiators, has been used to create elaborate 3D microarchitectures having feature sizes of <100 nm (18). In one instance, a two-photon fabricated hydrogel was reported that was responsive to UV illumination (19), although the photo-induced actuation was poorly defined, irreversible, and relatively slow. In addition, the study did not take advantage of the submicrometer resolution possible when multiphoton fabrication is used.

As an approach for creating smart materials that change volume in response to a chemical signal, proteins have been integrated as minor components into synthetic hydrogel networks to act as responsive elements. For example, hydrogels incorporating proteins such as antibodies (20) and calmodulin (21, 22) have been designed to change hydration degree in response to specific molecular triggers.

Natural and engineered proteins offer a diverse pool of physicochemical characteristics and functional properties. In addition to having the potential to undergo shape and hydration changes in response to chemical triggers, proteins contain a large number of weak acids and bases, similar to polymers used in pH-responsive hydrogels (5). Importantly, matrices composed of functional photocrosslinked proteins can be localized in 3D microenvironments by using multiphoton fabrication (23–27). Thus, multiphoton-fabricated protein structures could provide high-resolution 3D control over the topography of a stimuli-responsive material—facilitating greater mechanical functionality and incorporation of responsive hydrogels into more complex 3D devices—while potentially providing specificity (e.g., through ligand binding) over volumetric responses.

Here, we describe multiphoton fabrication of microscopic 3D hydrogels composed of photocrosslinked proteins and demonstrate their capabilities as chemically responsive micromechanical elements. Various proteins are used to construct materials with distinct swelling characteristics and are combined in various ratios to tune hydrogel responsivity. In addition, we demonstrate the feasibility for modulating a swelling response by introduction of a ligand (biotin) that stabilizes the protein (avidin) against denaturation. Protein microelements that bend in prescribed manners are created by rational incorporation of microscopic thickness and density gradients, and fabrication of responsive bacterial cages is used to harvest cell colonies after capture and incubation of motile cells.

Results and Discussion

Protein microstructures are fabricated by using an aqueous direct-write procedure in which a pulsed laser beam is focused to submicrometer dimensions to promote formation of crosslinks between oxidizable residues (28–30) via multiphoton excitation of a photosensitizer (23). This concept is illustrated in Fig. 1a. Here, a laser focal point was translated to create a protein hydrogel tether between a microsphere and a surface, providing the means to translocate the sphere by hydrogel contraction in response to an increase in bath ionic strength [supporting information (SI) Movie S1].

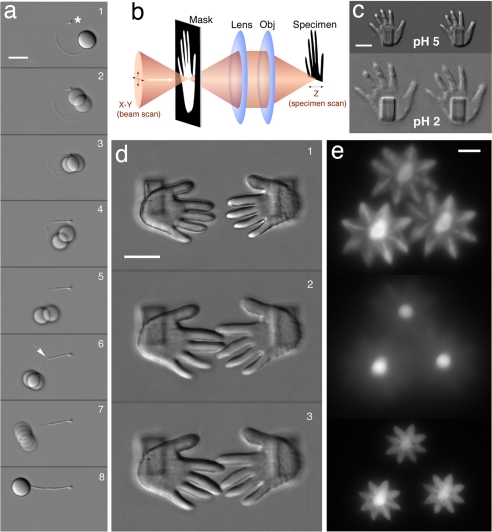

Fig. 1.

Free-form protein hydrogels. (a) Transport of a microobject by using hydrogel actuation. A PMMA microsphere was tethered to the surface of a glass coverslip (attachment at asterisk, 1) via a crosslinked BSA cable by scanning the focus of a titanium:sapphire laser (5 μm/sec) through concentrated protein solution. A brief increase in scan speed created a flexible joint in the central region of the cable (arrow in 6). Microsphere translocation (2-8; total duration of the movement was ≈3 sec) was initiated within a pH 3 solution by addition of Na2SO4 to a final concentration of 0.5 mM, causing the cable length to contract by ≈35% (Movie S1). (b) Simplified schematic showing fabrication of arbitrary 3D microstructures by using mask-directed multiphoton lithography (26). In this procedure, a negative transmissive or reflective photomask is placed in a plane conjugate to the fabrication plane, thereby limiting areas of exposure as the focal spot is raster scanned through solution (for simplification the orientation of the mask and specimen are the same). (c) BSA microhands mounted on BSA pedestals ≈4 μm from the coverslip surface (Upper) undergo reversible swelling after a decrease in bath pH from 5 to 2 (Lower). (d) The direct-write process allows BSA hydrogel microstructures to be fabricated with high resolution and arbitrary topography (1), providing abilities for effecting specific interactions between swelled states. Panels 2 and 3 demonstrate variable interdigitation of middle fingers achieved when the bath solution is cycled between pH 5 and pH 3. (e) Fluorescence images (from entrapped photosensitizer) showing stylized BSA microflowers swelled at pH 2.2 (HCl; Top) nested ≈7 μm from the surface on BSA “stems” (Middle; focus at coverslip surface), which undergo rapid contraction upon the addition of Na2SO4 to a final concentration of 1.0 mM (Bottom; Movie S2). (All scale bars, 10 μm.)

Elaborate, chemically responsive microstructures can be created by using a confocal scanner in combination with a negative photomask (Fig. 1b; ref. 26). Fig. 1c shows microscale hands fabricated in this manner that undergo large changes in volume in response to a pH step. Appropriate orientation of hand pairs results in interdigitation of individual fingers upon pH-induced expansion (Fig. 1d). In addition, microflowers can be fabricated atop stems that “bloom” under low ionic strength conditions and rapidly contract on addition of salts (Fig. 1e and Movie S2).

We and others have shown that direct-write protein matrices can retain ligand-binding and catalytic functionality similar to that of their component proteins (23–27), implying that native electrostatic and hydrophobic interactions governing protein conformation remain significantly intact within microstructures. However, at pH extremes, unfavorable electrostatic interactions can disrupt the native state and result in protein unfolding (31, 32). Accordingly, the swelling of BSA microhands at pH 2 shown in Fig. 1c is consistent with unfolding of albumin observed at pH values below ≈4.0 (32). Moreover, matrices can be cycled rapidly between swelled and condensed states in response to pH steps (Movie S3), indicating (as predicted) that denaturation is reversible. Importantly, the degree to which hydrogel microstructures swell and actuate was found to depend strongly on the crosslinking density of the matrix, a property that can be modulated both by protein concentration within the fabrication solution and laser exposure times (25, 26, 34) (Fig. S1). In addition, reversibility of structure swelling state was found to depend to some degree on crosslinking density and structure thickness, with denser and thicker structures returning more consistently to original form.

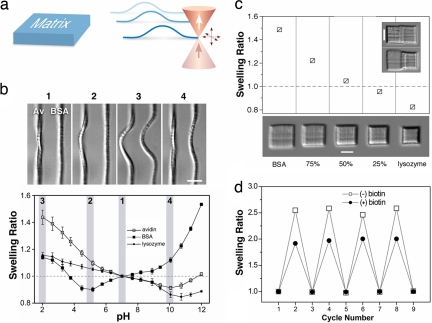

Previous approaches for creating responsive hydrogels with desired swelling characteristics have been based on laborious rational design of gel precursors (5, 6). In contrast, proteins represent a naturally diverse set of building blocks for engineering hydrogel responsivity. To characterize differences in swelling behaviors of protein hydrogels, we fabricated test structures (vertical arches, 3D rectangular matrices; Fig. 2a) with three commercially available proteins: BSA, avidin, and lysozyme. Hydrogels composed of these proteins exhibited distinct equilibrium swelling profiles (transition pH values, swelling ratios) over a broad pH range (Fig. 2b). In each case, hydrogels reached a minimum volume at pH values similar to the isoelectric points of the component proteins [pIavidin ≈ 10.0–10.5; pIBSA ≈ 4.7–4.9; pIlysozyme ≈ 11.0–11.3 (35, 36)], a finding consistent with pH dependence of protein solubility and hydration (32). Moreover, by fabricating protein matrices from a combination of BSA and lysozyme, microstructures could be tuned to expand or contract to varying degrees when the bath solution was stepped between pH values 7 and 11.9 (Fig. 2c), a result consistent with data acquired for the individual proteins (i.e., shown in Fig. 2b). Taken together, these results imply that a broad range of hydrogel swelling profiles will be possible by judicious selection [or engineering (37)] of protein building blocks. Further, protein matrices composed of avidin, which we previously have demonstrated retain biotin-binding functionality (23–25), showed attenuated swelling in acid and denaturant solutions in the biotin-bound state compared with the unbound state (Fig. 2d and Fig. S2). These results are consistent with the well characterized stabilizing effect of biotin on avidin (35, 38) and show the possibility for achieving microstructure actuation by means of biotin binding. By using engineered avidins (37, 39), biotin-induced actuation can be explored under a wider range of environmental conditions.

Fig. 2.

Protein-specific pH response. (a) Test structures (3D rectangular matrices and arches) were fabricated from solutions of avidin, BSA, and lysozyme. (b) (Upper) Protein arches composed of avidin and BSA were exposed to directed flow (from right to left) and subjected to abrupt pH steps. Panels 1-4 show hydrogel arches at pH values of 7, 5, 2, and 10, respectively (the pH corresponding to 1-4 is shaded in Lower). Depending on the solution pH, arches could be actuated individually (2 and 4) or in concert (3) (Movie S3). (Scale bar, 5 μm.) (Lower) Equilibrium swelling of rectangular matrices composed of avidin, BSA, and lysozyme show distinct swelling profiles. Swelling ratios (see Materials and Methods) were at a minimum near isoelectric points of the incorporated proteins. Error bars represent the standard deviation for four structures. (c) Structures fabricated from mixtures of BSA and lysozyme (percentages represent wt % of BSA relative to total protein) show intermediate swelling at pH 11.9 compared with 100% BSA and lysozyme structures. (Inset) Conjoined matrices (BSA, left; lysozyme, right) at pH 7 (upper) and pH 11.9 (lower). (Scale bars, 10 μm.) (d) A rectangular avidin matrix without biotin (open squares) was cycled reversibly between pH 7 (PBS; odd numbers) and pH 2 (HCl; even numbers). The microstructure then was exposed to a solution of 1 mM biotin (10 min) followed by rinsing (PBS; 10 rinses). Biotin binding reduced the lateral swelling at pH 2 by ≈25%, a result that remained essentially stable throughout pH cycling (filled circles).

We investigated the effects of the nonchaotropic salts NaCl, Na2SO4, and Na3PO4 on swollen BSA microstructures. Under basic conditions (pH 11.9 NaOH solution), introduction of high concentrations of these salts (>0.5 M) resulted in microstructure contraction. In acidic solutions (pH 2.2, HCl), however, much lower concentrations of sulfate (≈1–50 mM) caused a similar degree of contraction (Fig. S3), a result consistent with the efficient “salting out” activity of sulfate on BSA dissolved in low-pH solutions (40).

The speed at which a hydrogel responds to changes in its chemical environment depends in part on the accessibility of the gel interior to solution. Thus, structures that have short penetration distances (and thus rapid mass transfer) should exhibit relatively short response times (11, 41). As expected, high-aspect-ratio microstructures (i.e., those with the shortest diffusion paths) such as quasilinear tethers and rods underwent the most rapid volume changes in these studies. For large steps in pH or ionic strength (e.g., changes of at least 2 pH units or addition of more than 50 mM sodium sulfate) the half-time (t1/2) for changes in size can be <1 sec (Movie S4).

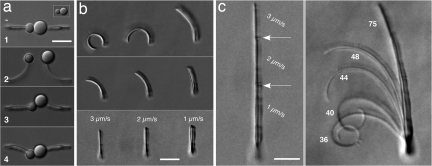

Direct-write protein hydrogels offer the possibility for effecting novel 3D microactuation based on spatially defined gradients in matrix properties. Matrices of differing density and thickness can be fabricated by irradiating solution regions at different intensities or for various periods, yielding microdomains with distinct capacities for expansion and contraction. Gradients in matrix thickness and density can be established across the width of a rod, for example, by raster scanning the laser focus in a transverse direction with varying dwell times as the sample solution is translated along the rod axis at a uniform velocity (Fig. S4). By using this design principal, one edge of a protein rod can be designed to expand and contract to a greater degree than its opposing edge, causing the rod to bend in definable manners in response to changes in chemical environment.

Microscopic hydrogel components can be assembled into highly organized arrangements, providing capabilities for sophisticated micromechanical motion. Bendable rods can be arranged to create chemically mediated gates (Fig. 3a) and can be used to transport microscale objects over extended distances (Fig. S5). In addition, rods designed to bend differentially in response to ionic-strength changes (by changing axial scan speed; Fig. 3b) can be assembled in a linear sequence of increasing responsivity, creating fern-like structures that coil and unfurl in response to a chemical trigger (Fig. 3c; Movie S5). Design of microscale programmable folding geometries (42) should be feasible by precise control of scan paths and exposure levels.

Fig. 3.

Tunable bending of gradient rods. (a) Gradient rods tether microspheres to form a switchable gate (1) that opens when the fabrication solution is replaced with a pH 3 HCl solution (2). Addition of 250 μM Na2SO4 causes gate closure (3). Addition of 10 mM Na2SO4 further contracts gradient rods, repositioning the microspheres (4). (b) Protein rods incorporating a thickness gradient across the width of the rod were fabricated (Bottom; 40%, wt/vol, protein solution; pH ≈7.5) and rinsed (pH 7, Middle; pH 3, Top). The degree of curvature varies according to the axial scan speed used during fabrication. Rods are attached to the coverglass at their lowest positions in the images. (c) Multiple components were assembled into a single structure (Left) and expanded at pH 3 by using HCl (Right, structure 36). Abrupt change in ionic strength induced contraction of the multicomponent rod (Right, structures 40, 44, 48, and 75); see Movie S5 caption for conditions. Numbers indicate frame position from Movie S5; time increment for a change of 1 unit is 0.2 sec. (Scale bars, 10 μm.)

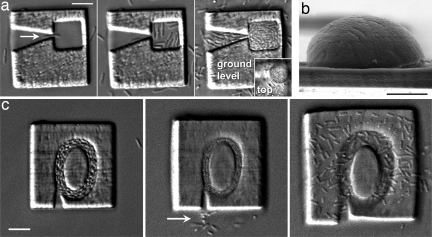

We previously have shown that protein-based microchambers are well suited for capture and growth of motile cells such as Escherichia coli (26), in part because the porosity of crosslinked protein matrices provides efficient transfer of nutrients and waste materials across microchamber walls. It is possible to trap individual bacteria (26) and to grow up a genetically homogeneous population to extremely high densities (≈1011 cells per ml) within these chambers. In our previous work, microchambers containing cells were sealed by using a biocompatible microfabrication approach to plug chamber inlets (26). However, microchamber geometries also can be designed to trap cells passively (Fig. 4a). Incubation in nutrient-rich conditions facilitates development of densely packed cell colonies, which can lead to remarkable expansions of enclosure surfaces (Fig. 4b). Here, expansion is principally confined to the thinnest, and thus most elastic, surface (the chamber tops).

Fig. 4.

Dynamic cell enclosures. Microenclosures composed of protein matrices can be used to trap, incubate, and release E. coli cells. (a) (Left) Differential interference contrast (DIC) image showing a motile E. coli cell (arrow) directed through an aperture slightly larger than the cell diameter (≈1 μm) into a microchamber (≈3 μm height, coverslip to ceiling) composed of crosslinked BSA. (Middle). About 1 min after cells are introduced into the medium, additional cells have entered the chamber, organizing along internal walls. After an ≈30-min fill, chamber loading is terminated. (Right) Twelve hours after incubation in nutrient-rich medium, cells are densely packed into the chamber, where cell division has directed vertical expansion of chamber ceiling (Inset, focused ≈10 μm above the initial height of the ceiling). (b) Scanning electron micrograph of a similar cell-colony dome showing significant vertical expansion of protein matrix. The tear at the right side of the base occurred during preparation of the sample for microscopy. (c) Abrupt change in bath pH (7 to 12.2) causes temporary compression of the internal chamber, releasing a few cells (arrow, Middle), and eventually disrupts the chamber substrate interface (Right, when inverted microscopy is used, cells are seen in between the glass substrate and the microchamber; see Movie S6). (Scale bars, 5 μm.)

By subjecting such enclosures to relatively large chemical changes (e.g., a pH step to 12.2), the hydration level of chamber walls can be dramatically altered, disrupting the integrity of the microchamber–substrate interface to achieve release of trapped cells (Fig. 4c and Movie S6) for further analysis and incubation. The relative hardiness of bacteria allows cells released under these conditions to exhibit normal growth, cell division, and motility upon return to nutrient-rich medium and may allow the volume of such cell enclosures to be purposefully controlled during division and growth. The dynamic properties of these chambers should enable studies regarding cell motility, communication, and population-based behaviors, which require precise control during interrogation of individual cells, single-cell lineages, and small populations of cells.

The possibility for modifying the size and shape of protein-based microstructures by using ligands in place of steps in pH or ionic strength would open practical opportunities for exploring the use of these materials in mammalian cell studies. Importantly, we previously have shown that it is feasible to modify cell culture environments dynamically—including those containing relatively sensitive culture primary neurons—by using protein microfabrication without causing prohibitive damage to cells (23, 25, 26).

These studies provide a foundation to achieve more specific microactuation based on conformational changes induced by ligand binding and release (20–22). Moreover, the ability to precisely define the overall 3D microarchitecture of hydrogels in tandem with the engineering of internal density gradients offers unique opportunities for the design of smart materials.

Materials and Methods

Materials.

BSA, avidin, and poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA) microparticles were purchased from Equitech-Bio (catalog no. BAH64–0100), Molecular Probes (A-887), and Polysciences (19130), respectively. Biotin was purchased from Fisher Scientific (BP232). Lysozyme (L-6876), methylene blue (M-4159), and flavin adenine dinucleotide (F-6625) were supplied by Sigma-Aldrich. All reagents were used as received.

Hydrogel Fabrication and Characterization.

Hydrogels composed of photocrosslinked protein were fabricated on untreated no. 1 microscope coverslips by using the output of a mode-locked titanium:sapphire laser (Tsunami; Spectra Physics) operating at 730–740 nm. The laser focus was raster scanned with a commercial confocal scanner (Bio-Rad MRC600). Hydrogel structures depicted in Figs. 1 c and d and 4 were further defined by using transparency-based photomasks in which a negative of the desired structure was inserted in a plane conjugate to the fabrication plane (26). Structures depicted in Fig. 1e were fabricated in a similar manner, using a reflectance mask (digital micromirror device) in place of a transmission mask. Rods and tethers were attached to a coverslip surface by beginning a scan at or below the surface and manually translating the focal point into solution by using the microscope fine focus as the stage was scanned laterally. Generally, the distance of travel into solution was ≈2 μm, and travel was completed within the first few lateral micrometers, producing structures similar to that in Fig. S3c.

The laser output was adjusted by using optics to approximately fill the back aperture of an oil-immersion objective (Zeiss 100× Fluar, 1.3 numerical aperture) situated on a Zeiss Axiovert inverted microscope system. Desired powers were obtained by attenuating the laser beam by using a half-wave plate/polarizing beam-splitter pair. To extend structures along the z dimension (i.e., along the optical axis), the position of the laser focus was translated manually within fabrication solutions by using the microscope fine focus adjustment.

Microstructures composed of photocrosslinked protein were fabricated from solutions containing protein at 320–400 mg/ml and either methylene blue (1.2–3 mM) or flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD; 5 mM) as a photosensitizer. High concentrations of protein in solution facilitate fabrication of robust microstructures. However, fabrication can be accomplished using protein solutions at concentrations as low as ≈1–10 ng/ml (27). Although some proteins undergo multiphoton crosslinking more efficiently than others, a broad range of proteins can be used (e.g. glutamate dehydrogenase, cytochrome c, aldolase, laminin, ferritin, myoglobin).

Equilibrium swelling data depicted in Fig. 2b was acquired by 3-min incubation of microstructures in phosphate-buffered solutions (0.5 mM) of pH 2.02, 2.63, 3.26, 3.78, 4.48, 5.17, 5.76, 6.30, 7.00, 7.66, 8.19, 8.90, 9.41, 10.06, 10.73, 11.33, and 12.00. Rectangular areas (A) were measured ≈3 μm above the coverslip surface, and equilibrium swelling ratios were calculated as the ratio A/A0, where A0 = area at pH 7. Microstructures were imaged by using the Axiovert microscope with differential interference contrast (DIC) optics and a 12-bit 1,392 × 1,040 element CCD (Cool Snap HQ; Photometrics). Wide-field fluorescence imaging of entrapped photosensitizer was performed on the Axiovert microscope, which was equipped with a mercury-arc lamp and standard “red” and “green” filter sets (Chroma). Except where otherwise noted, ionic strength contraction was induced by adding concentrated salt solution to the well containing a microstructure in solution defined by HCl or NaOH (e.g., 5 μl of salt solution added to 495 μl of solution in the well).

Specimens for scanning electron microscopy (SEM) were fixed in 3.5% glutaraldehyde solution for 20 min and dehydrated by using 10-min sequential washes (2:1 ethanol/H2O; twice in 100% ethanol; 1:1 ethanol/methanol; 100% methanol; all solutions stated as vol/vol), allowed to air-dry for 3 h, and sputter-coated to a nominal thickness of 12–15 nm with Au/Pd.

Bacterial Cell Culture.

The E. coli strain RP9535 (smooth-swimming, ΔcheA) were grown aerobically in tryptone broth (32°C) and harvested at mid-logarithmic phase. Cells were diluted 100-fold into PBS (Hyclone, pH 7.0) and introduced into 500 μl wells containing microchambers fabricated on glass coverslips shown in Fig. 4. Trapped cells were incubated for ≈12 h in tryptone broth (22°C). The cell chamber was expanded to release cells by using pH 12.2 solution (NaOH). Cells released by using these conditions exhibited normal growth, cell division, and motility upon return to the nutrient-rich medium.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

We thank J. Parkinson for E. coli strain RP-9535. This work was supported by grants from the National Science Foundation (0317032) and the Robert A. Welch Foundation (F-1331). J.B.S. is a Fellow of the Institute for Cellular and Molecular Biology.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0709571105/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Kay ER, Leigh DA, Zerbetto F. Synthetic molecular motors and mechanical machines. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2007;46:72–191. doi: 10.1002/anie.200504313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peppas NA, Hilt JZ, Khademhosseini A, Langer R. Hydrogels in biology and medicine: From molecular principles to bionanotechnology. Adv Mater. 2006;18:1345–1360. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sidorenko A, Krupenkin T, Taylor A, Fratzl P, Aizenberg J. Reversible switching of hydrogel-actuated nanostructures into complex micropatterns. Science. 2007;315:487–490. doi: 10.1126/science.1135516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kobatake S, Takami S, Muto H, Ishikawa T, Irie M. Rapid and reversible shape changes of molecular crystals on photoirradiation. Nature. 2007;446:778–781. doi: 10.1038/nature05669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gil ES, Hudson SM. Stimuli-responsive polymers and their bioconjugates. Prog Polym Sci. 2004;29:1173–1222. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alexander C, Shakesheff KM. Responsive polymers at the biology/materials science interface. Adv Mater. 2006;18:3321–3328. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jager EW, Smela E, Inganas O. Microfabricating conjugated polymer actuators. Science. 2000;290:1540–1545. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5496.1540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Terray A, Oakey J, Marr DW. Microfluidic control using colloidal devices. Science. 2002;296:1841–1844. doi: 10.1126/science.1072133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grier DG. A revolution in optical manipulation. Nature. 2003;424:810–816. doi: 10.1038/nature01935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chang ST, Paunov VN, Petsev DN, Velev OD. Remotely powered self-propelling particles and micropumps based on miniature diodes. Nat Mater. 2007;6:235–240. doi: 10.1038/nmat1843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beebe DJ, et al. Functional hydrogel structures for autonomous flow control inside microfluidic channels. Nature. 2000;404:588–590. doi: 10.1038/35007047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee S, Eddington D, Kim Y, Kim W, Beebe D. Control mechanism of an organic self-regulating microfluidic system. J Microelectromech Syst. 2003;12:848–854. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eddington DT, Beebe DJ. A valved responsive hydrogel microdispensing device with integrated pressure source. J Microelectromech Syst. 2004;13:586–593. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Agarwal A, Sridharamurthy S, Beebe D. Programmable autonomous micromixers and micropumps. J Microelectromech Syst. 2005;14:1409–1421. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dong L, Agarwal AK, Beebe DJ, Jiang H. Adaptive liquid microlenses activated by stimuli-responsive hydrogels. Nature. 2006;442:551–554. doi: 10.1038/nature05024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lei M, Gu YD, Baldi A, Siegel RA, Ziaie B. High-resolution technique for fabricating environmentally sensitive hydrogel microstructures. Langmuir. 2004;20:8947–8951. doi: 10.1021/la048719y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tirumala V, Divan R, Ocola L, Mancini D. Direct-write e-beam patterning of stimuli-responsive hydrogel nanostructures. J Vac Sci Technol B. 2005;23:3124–3128. [Google Scholar]

- 18.LaFratta C, Fourkas J, Baldacchini T, Farrer R. Multiphoton Fabrication. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2007;46:6238–6258. doi: 10.1002/anie.200603995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Watanabe T, et al. Photoresponsive hydrogel microstructure fabricated by two-photon initiated polymerization. Adv Funct Mater. 2002;12:611–614. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miyata T, Asami N, Uragami T. A reversibly antigen-responsive hydrogel. Nature. 1999;399:766–769. doi: 10.1038/21619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ehrick JD, et al. Genetically engineered protein in hydrogels tailors stimuli-responsive characteristics. Nat Mater. 2005;4:298–302. doi: 10.1038/nmat1352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Murphy WL, Dillmore WS, Modica J, Mrksich M. Dynamic Hydrogels: Translating a protein conformational change into macroscopic motion. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2007;46:3066–3069. doi: 10.1002/anie.200604808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaehr B, Allen R, Javier DJ, Currie J, Shear JB. Guiding neuronal development with in situ microfabrication. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:16104–16108. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407204101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Allen R, Nielson R, Wise DD, Shear JB. Catalytic three-dimensional protein architectures. Anal Chem. 2005;77:5089–5095. doi: 10.1021/ac0507892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kaehr B, et al. Direct-write fabrication of functional protein matrixes using a low-cost Q-switched laser. Anal Chem. 2006;78:3198–3202. doi: 10.1021/ac052267s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kaehr B, Shear JB. Mask-directed multiphoton lithography. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:1904–1905. doi: 10.1021/ja068390y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pitts JD, Campagnola PJ, Epling GA, Goodman SL. Submicron multiphoton free-form fabrication of proteins and polymers: Studies of reaction efficiencies and applications in sustained release. Macromolecules. 2000;33:1514–1523. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Spikes JD, Shen HR, Kopeckova P, Kopecek J. Photodynamic crosslinking of proteins. III. Kinetics of the FMN- and Rose Bengal-sensitized photooxidation and intermolecular crosslinking of model tyrosine-containing N-(2-hydroxypropyl)methacrylamide copolymers. Photochem Photobiol. 1999;70:130–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shen HR, Spikes JD, Kopecekova P, Kopecek J. Photodynamic crosslinking of proteins. II. Photocrosslinking of a model protein—ribonuclease A. J Photochem Photobiol B. 1996;35:213–219. doi: 10.1016/s1011-1344(96)07300-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shen HR, Spikes JD, Kopecekova P, Kopecek J. Photodynamic crosslinking of proteins. I. Model studies using histidine- and lysine-containing N-(2-hydroxypropyl) methacrylamide copolymers. J Photochem Photobiol B. 1996;34:203–210. doi: 10.1016/1011-1344(96)07286-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Matthew JB, Gurd FR. Stabilization and destabilization of protein structure by charge interactions. Methods Enzymol. 1986;130:437–453. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(86)30020-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Scopes RK. Protein Purification: Principles and Practice. New York: Springer; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Carter DC, Ho JX. Structure of serum albumin. Adv Protein Chem. 1994;45:153–203. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3233(08)60640-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Basu S, Wolgemuth CW, Campagnola PJ. Measurement of normal and anomalous diffusion of dyes within protein structures fabricated via multiphoton excited cross-linking. Biomacromolecules. 2004;5:2347–2357. doi: 10.1021/bm049707u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Green NM. Avidin. Adv Protein Chem. 1975;29:85–133. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3233(08)60411-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Malamud D, Drysdale JW. Isoelectric points of proteins: A table. Anal Biochem. 1978;86:620–647. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(78)90790-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Laitinen OH, Hytonen VP, Nordlund HR, Kulomaa MS. Genetically engineered avidins and streptavidins. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2006;63:2992–3017. doi: 10.1007/s00018-006-6288-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gonzalez M, Argarana CE, Fidelio GD. Extremely high thermal stability of streptavidin and avidin upon biotin binding. Biomol Eng. 1999;16:67–72. doi: 10.1016/s1050-3862(99)00041-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Laitinen OH, et al. Biotin induces tetramerization of a recombinant monomeric avidin. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:8219–8224. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007930200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Arakawa T, Timasheff SN. Mechanism of protein salting in and salting out by divalent cation salts: Balance between hydration and salt binding. Biochemistry. 1984;23:5912–5923. doi: 10.1021/bi00320a004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhao B, Moore JS. Fast pH- and ionic strength-responsive hydrogels in microchannels. Langmuir. 2001;17:4758–4763. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Klein Y, Efrati E, Sharon E. Shaping of elastic sheets by prescription of non-Euclidean metrics. Science. 2007;315:1116–1120. doi: 10.1126/science.1135994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.