Abstract

The FACT complex is a conserved cofactor for RNA polymerase II elongation through nucleosomes. FACT bears histone chaperone activity and contributes to chromatin integrity. However, the molecular mechanisms behind FACT function remain elusive. Here we report biochemical, structural, and mutational analyses that identify the peptidase homology domain of the Schizosaccharomyces pombe FACT large subunit Spt16 (Spt16-N) as a binding module for histones H3 and H4. The 2.1-Å crystal structure of Spt16-N reveals an aminopeptidase P fold whose enzymatic activity has been lost. Instead, the highly conserved fold directly binds histones H3–H4 through a tight interaction with their globular core domains, as well as with their N-terminal tails. Mutations within a conserved surface pocket in Spt16-N or posttranslational modification of the histone H4 tail reduce interaction in vitro, whereas the globular domains of H3–H4 and the H3 tail bind distinct Spt16-N surfaces. Our analysis suggests that the N-terminal domain of Spt16 may add to the known H2A–H2B chaperone activity of FACT by including a H3–H4 tail and H3–H4 core binding function mediated by the N terminus of Spt16. We suggest that these interactions may aid FACT-mediated nucleosome reorganization events.

Keywords: histone chaperone, histone modifications, protein evolution, site-directed mutagenesis, transcription

Nucleosomes create a natural barrier to RNA polymerase II (Pol II) progression. Transcription of histone-wrapped DNA thus requires factors that promote nucleosome remodeling, such as the histone chaperone FACT (facilitates chromatin transcription), which in human cells purifies as a heterodimer of Spt16 and SSRP1 (1, 2).

FACT is a highly conserved complex (2–5). In fungi, SSRP1 is largely encoded by POB3, whereas NHP6 encodes the archetypal HMG-box of SSRP1. The gene for the Spt16 subunit is essential in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Schizosaccharomyces pombe, probably reflecting important chromatin-related functions in transcription, replication, and DNA repair (4, 6–9). Genetic screens identified Spt16 as a factor whose mutation restores the expression of a Ty1 transposon-silenced reporter gene by promoting its cryptic transcription, known as a suppressor of Ty1 phenotype, [Spt−] (4, 7, 10, 11). Several POB3 alleles genes display [Spt−] phenotypes (12), indicating that the maintenance of correct chromatin structure involves Pol II cofactors such as FACT (13). Indeed, FACT acts as a coactivator of transcriptional initiation and elongation (14), and many Spt16 alleles display genetic interactions with basal transcription factors. Furthermore, FACT subunits biochemically interact with the Pol II elongation complex Paf1 (15), bind the coding region of transcribed Pol II genes, and are recruited to inducible genes upon activation (16–19).

FACT's biological roles in transcription (and replication) may stem from its histone chaperone activity (20, 21). Histone chaperones stimulate reactions involving the transfer of histones (22), thereby mediating chromatin reorganization. At the molecular level, FACT binds nucleosomes and destabilizes interactions between H2A–H2B dimers and (H3–H4)2 tetramers (20). Mechanistically this suggests that FACT may help transcription and replication by removing one H2A–H2B dimer from nucleosomes, thus relieving the barrier to polymerase progression. After Pol II passage, FACT may restore the proper chromatin state (14, 20).

There is little mechanistic insight into how FACT may be able to perform its chaperoning functions. In particular, it is unclear how it interacts with histones. To start dissecting the structure and function of the essential Spt16 subunit of FACT, we sought to identify the molecular functions inherent to this >100-kDa multidomain protein. Structural information on FACT exists for the HMG-like module Nhp6A from S. cerevisiae (23), which binds DNA, and for the middle domain of S. cerevisiae Pob3 (24), which resembles a double PH-like fold and interacts with replication protein A. The highly conserved Spt16 consists of three domains: an acidic segment at the C terminus (10) that is required for binding histones H2A–H2B in vitro (20) and resembles the acidic domains of Nap1, nucleolin, and Asf1 (25–27); two central domains, one of which interacts with Pob3 (21, 24); and an N-terminal region of ≈450 residues (Spt16-N) showing homology with aminopeptidases (28). We were intrigued by the presence of a peptidase-like domain within this essential and conserved histone chaperone [supporting information (SI) Fig. S1]. We have characterized biochemical functions of Spt16-N by combining structural approaches with quantitative binding studies and site-directed mutagenesis.

Results

A Catalytically Inactive Enzyme Fold Interacts with Histones H3–H4.

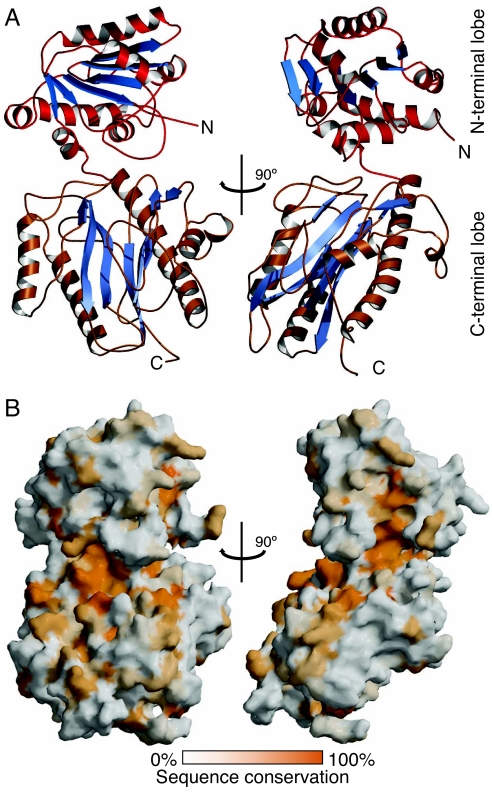

We expressed and crystallized the N-terminal “peptidase” module of the S. pombe FACT complex Spt16. The structure of the domain (residues 1–442, Spt16-N) was solved and refined to 2.1-Å resolution (Table S1 and Materials and Methods). Our structure is highly similar to the recently published structure of the related domain from S. cerevisiae (29), revealing the conserved pita-bread fold (C-terminal lobe; residues 178–442) of aminopeptidases (30), preceded by a smaller domain (N-terminal lobe; residues 1–174) (Fig. 1A). Structural homology searches return a bacterial prolidase and creatinase [Protein Data Bank ID codes 1CHM and 1PV9 (31, 32); DALI (55) Z-scores 30.5 and 30.3, respectively]. Their catalytic domains closely align with the corresponding segment in Spt16 (rmsd between ≈300 Cα atoms is <2.5 Å). Importantly, neither residues required for divalent cation coordination in metal-dependent aminopeptidases (30) nor the catalytic histidine in creatinase (32) are conserved in Spt16 (Fig. S2 A and B). Spt16-N may thus have evolutionary diverged from aminopeptidases.

Fig. 1.

Structure of the aminopeptidase domain of Spt16. (A) View of the N-terminal domain (residues 1–442) of S. pombe FACT subunit Spt16 in two orientations. The module consists of an N-terminal lobe (Upper) and a larger C-terminal lobe (Lower) that is structurally related to aminopeptidases. (B) The Spt16-N domain is conserved across eukaryotes. Surfaces are colored according to sequence conservation, ranging from dark orange for invariant residues to white for variable residues, identifying a conserved pocket in the C-terminal lobe (the pita-bread fold) of Spt16, which corresponds to the catalytic site in active aminopeptidase enzymes, and a second conserved pocket in the N-terminal lobe. The relative orientation of the two structures is the same as in A.

The Spt16-N module harbors two surface patches that are strictly conserved among its orthologues (Fig. 1B and Fig. S1). One maps to the center of the “pita-bread core,” and a second is found on the N-terminal lobe (Fig. 1B). The presence of conserved surface-exposed residues in this peptidase domain prompted us to test whether Spt16-N may bind proteins. Inferred mechanisms for FACT function in chromatin reorganization involve a chaperone activity for H2A–H2B histone dimers, likely mediated by the C terminus of Spt16 (20, 22). We tested whether the conserved Spt16-N domain may bind histones using GST pull-down assays between Spt16-N and recombinant core histones H2A–H2B or H3–H4, as well as native Drosophila octamers. Surprisingly, the Spt16-N peptidase module directly interacts with both recombinant and native histones H3–H4 (Fig. 2 A and B). Stable H3–H4 association occurs even under high ionic strength, in contrast to histones H2A–H2B, which do not bind Spt16-N specifically (Fig. 2A). Isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) assays confirm binding of recombinant H3–H4 to Spt16-N under physiological salt concentrations (Fig. S3A). To test whether the interacting proteins form a stable complex, we measured the interaction between the proteins by comigration on size-exclusion chromatography. Spt16-N, together with refolded histone H2A–H2B dimers, shows no shift in its elution volume (Fig. S2C). Thus, H2A–H2B do not bind Spt16-N under these conditions, consistent with Spt16 requiring its acidic C terminus for H2A–H2B interaction (20). In contrast, we observe comigration of Spt16-N with H3–H4, as indicated by the shift to higher molecular masses of Spt16-N when bound to histones H3–H4 (Fig. 2C). There is an equilibrium between H3–H4 dimers and tetramers that depends on pH and protein and salt concentration (33). Based on column calibration using molecular mass markers, the two shifted peaks correspond approximately to a dimer of H3–H4 bound to one Spt16-N domain, as well as two Spt16-N domains bound to a H3–H4 tetramer.

Fig. 2.

Spt16-N interacts with histones H3–H4. (A) GST pull-down assays of recombinant core histones with immobilized Spt16-N. Assays were conducted with increasing stringency of salt concentration in the washing buffer. (B) GST pull-down assays of native Drosophila melanogaster core histone octamers with immobilized GST-Spt16-N. Input and pulldown lanes are from different parts of the same SDS/PAGE gel. (C) Cofractionation of Spt16-N with purified H3–H4 histones by size-exclusion chromatography. Spt16-N incubated with H3–H4 yields two peaks (dark blue; running at a calculated molecular mass of 185 and 90 kDa), corresponding to a tetramer and dimer of H3–H4 bound to two or one molecules of Spt16-N, respectively. Consistently, free H3–H4 also yields two species (at 102 and 47 kDa), whose molecular masses match those of tetramers and dimers (medium blue). Light blue shows the elution profiles for Spt16-N alone, which runs as a monomer (at 50 kDa). Because histones H3–H4 have N-terminal tails, their retention times are slightly larger than expected for their mass. The void volume for the Superdex 200 10/300 GL column is at 8.2 ml.

To resolve the stoichiometry of the complex extrapolated from our size-exclusion chromatography, we have performed analytical ultracentrifugation. The analysis shows that Spt16-N forms a 1:1 complex with H3–H4 dimers and, to a lesser extent, a peak that fits the molecular masses of two Spt16-N modules with four H3–H4 histones (Fig. 3A). Taken together, our structural and biochemical data reveal that Spt16-N uses an ancient enzymatic fold to mediate molecular interactions with histones H3–H4 in vitro.

Fig. 3.

Spt16-N recognizes the globular core of tailless histones H3–H4. (A) Analytical ultracentrifugation of the Spt16-N histones H3–H4 complex reveals a 1:1 stoichiometry. Shown are three peaks with apparent molecular masses corresponding to (x1) free histones H3–H4 dimers, (x2) one Spt16-N molecule plus one H3–H4 dimer, and (x3) two molecules of Spt16-N plus one H3–H4 tetramer (or two H3–H4 dimers). (B) Gel-filtration profile (Upper) and SDS/PAGE gel (Lower) for the interaction between Spt16-N and the tailless, globular domains of histones H3–H4.

Spt16-N Interacts with the Globular Domains of Histone H3 and H4.

To determine whether Spt16-N binds histones H3–H4 through their globular core domains or through their N-terminal tails, we used gel-filtration and GST pull-down assays to measure the binding of Spt16-N to the globular domains of tailless H3 and H4 complexes (Fig. 3B and Fig. S3B). The assays reveal that Spt16-N makes direct interactions with the globular domains of histone H3–H4. Furthermore, the interaction with H3–H4 cores is equally stable to that of full-length H3–H4 even at high salt concentrations (Figs. S2A and S3B). This suggests that the globular domains are a major contributor for Spt16-N binding in vitro. Mutagenesis of either of the two conserved surface regions in Spt16-N (Fig. 1B) does not disrupt binding to H3–H4 globular domains (Fig. S3B), indicating that the H3–H4 interaction is mediated by a distinct region on the extended surface of the Spt16-N module.

Spt16-N Interacts with Histone H3 and H4 Tails.

Many chromatin factors recognize native or posttranslationally modified residues on histones (34–36), usually through conserved ligand-binding cavities. Because Spt16-N bears two conserved surface pockets, we determined whether Spt16-N might recognize H3 or H4 N-terminal tails. We quantitated binding of Spt16-N to tail peptides using ITC. Our in-solution assays reveal a high affinity of Spt16-N for the N-terminal tails of histone H3 (KD = 11 μM) and H4 (KD = 3 μM) (Fig. 4 A–C). The interaction between histone tails and Spt16-N is strongly salt-dependent (data not shown; histone tail binding modules typically bind their ligands only at low salt in vitro), in contrast to interaction with the globular domain. Consistent with our GST pull-down and gel-filtration assays (Fig. 2 A and C), Spt16-N does not detectably interact with H2B tails (Fig. 4A). Furthermore, the calorimetry shows that S. pombe Spt16-N binds H3 and H4 tails with 1:1 stoichiometry (Fig. 4B), suggesting the existence of a specific surface (or surfaces) on Spt16-N that is responsible for binding H3 and H4 tails. We therefore asked whether the two conserved surface patches in Spt16-N (Fig. 1B) mediate the interaction with H3 and H4 tails. Thus, we replaced the functional groups of conserved residues in the central cavity (Fig. 4D) to alanine. These mutants do not affect the dissociation constant for H3 or H4 peptides in vitro (Fig. 4C). This suggests that the region corresponding to the catalytic site of aminopeptidases may not mediate interactions with H3/H4 tails.

Fig. 4.

Spt16-N directly binds the N-terminal tails of histone H3 and H4 using different pockets. (A) ITC profile for the binding of H4 N-terminal tail peptide (1–35; black) to Spt16-N in comparison to H2B tail (blue), which does not bind Spt16-N. The Inset shows equilibrium dissociation constants (KD) for different peptides, including histone H4 diacetylated at K8/K16 (H4 K8Ac/K16Ac) or monomethylated at K20 (H4 K20me1). (B) Fitting of the experimental data to an equilibrium binding profile for the unmodified H4 (1–35) peptide. The Inset shows the stoichiometry of binding (N), the KD, enthalpy ΔH (kcal·mol−1), and entropy ΔS. (C) KD for the binding of H4 and H3 peptides to wild-type and engineered mutant Spt16-N. (D) Overview of the site-directed mutants in the two putative ligand binding pockets of Spt16-N (yellow balls denote the mutated positions). The figure also shows a second Spt16-N molecule (gray) in the asymmetric unit of the crystal that interacts with Spt16-N through the N-terminal peptide sequence (in cyan). The framed box indicates the region of Spt16-N shown in E. (E) The second, conserved pocket of Spt16-N locates to the N-terminal lobe of the module (surface view; color coding as in Fig. 1B) and is in contact with N-terminal residues of a second Spt16-N molecule in the asymmetric unit (ball-and-stick). (F) Key residues in Spt16-N (ball-and-stick, yellow backbone) mediating the crystal contact to the Stp16-N N terminus (ball-and-stick, cyan backbone).

A second highly conserved patch maps to a groove within the N-terminal lobe (Fig. 1B). Interestingly, this surface is in direct contact with the N terminus of a neighboring molecule in our crystals. The N terminus of a second molecule in the crystal binds the Spt16-N pocket in an extended conformation (Fig. 4 E and F). A similar interaction occurs in a second crystal form (form B; Fig. S4 and Table S1), hinting at a peptide-binding role for this pocket. Mutation of the highly conserved Ser-83 and Lys-86 residues, which contribute to this intermolecular crystal interaction, does not change the affinity for the H3 tail but reduces binding to the H4 peptide ≈15-fold (Fig. 4C). Our site-directed mutagenesis analysis thus maps the binding of the histone H4 tail to this conserved pocket within the N-terminal lobe of Spt16-N.

Distinct histone marks can be recognized by specific protein modules. Thus, we tested the specificity of H4 tail peptide interaction by incubating Spt16-N with H4 peptides carrying known posttranslational modifications of yeast H4 (37). Diacetylation of H4 K8/K16, a mark of actively transcribed chromatin, or monomethylation of H4 K20 reduces but does not ablate the binding of H4 peptides to Spt16-N (Fig. 4A). These data show that the Spt16-N module can interact with both native and modified H4 N-terminal tails.

Together, our biochemical and mutational experiments show that Spt16-N is a histone binding module for H3 and H4, which interacts with the N-terminal tail of H3 and H4, as well as with their globular domains. Furthermore, Spt16-N recognizes H3 and H4 tails through distinct surfaces and associates with the globular domains of H3–H4 to form a biochemically defined protein assembly.

Discussion

The evolutionary history of transcription and chromatin factors is largely unclear. Spt16-N is a good example of a eukaryotic transcription regulator derived from an ancient enzyme fold. Other aminopeptidases have lost their catalytic function to acquire vital chromatin and transcription roles, including Taf2, part of the promoter selectivity factor TFIID, and Ebp1 (28, 38, 39), a factor involved in transcription and translation.

Here we identify a H3–H4 globular domain binding role for the N-terminal domain of the FACT subunit Spt16. Furthermore, the Spt16-N aminopeptidase module also binds directly to histone H3 and H4 tails. Our structure also reveals a conserved surface pocket involved in H4 tail binding. Ser-83 and Lys-86 in this pocket directly mediate peptide binding through a contact with a neighboring molecule in the crystal. Mutation of these residues reduces H4-tail affinity but retains high-affinity binding to H3 tails and interaction with H3–H4 globular cores. Spt16-N thus likely bears independent H3 tail and H3–H4 core binding surfaces. Together, our combined data implicate the S. pombe Spt16 peptidase fold in an unexpected FACT-mediated binding function for histones H3 and H4.

S. cerevisiae FACT is an essential nuclear complex involved in transcriptional regulation and chromatin remodeling. Genetic experiments in S. cerevisiae suggest that the Spt16 N-terminal region is dispensable for several FACT functions (21). Similarly, we observe that fission yeast strains expressing ectopically Spt16 mutant proteins that lack the peptidase fold (Spt16-ΔN) are viable (data not shown). In fact, recent findings indicate that the budding yeast N-terminal domain (Spt16-NTD) and the middle domain of Pob3 (Pob3-M) may mediate partially redundant functions and account for the viability of either single mutant (29). Indeed, both Spt16-NTD and the middle domain of Pob3 genetically interact with histones, and pob3-M spt16-NTD double mutants display synthetic defects (24, 29).

At the structural level, S. pombe and S. cerevisiae Spt16-N exhibit a high degree of structural similarity (rmsd is 1.5 Å between 410 corresponding Cα atoms), in particular with regard to the two conserved surface pockets (Fig. 1B), one of which we show is involved in histone H4 tail binding. Our functional analysis of the S. pombe Spt16-N module and the genetics in S. cerevisiae together argue for a role of the peptidase domain in FACT-mediated chromatin remodeling. FACT has been proposed to facilitate polymerase progression on chromatin templates by removing H2A–H2B from nucleosomes and reassembling the octamer in its wake (14, 20). We now show that Spt16-N associates with histones H3–H4 cores and tails, suggesting that the large subunit of FACT may contribute to the binding, eviction, and/or deposition of all histones. Alternatively, Spt16 interaction with H3–H4 could participate in the tethering of nucleosome fragments after RNA polymerase passage, promote H2A–H2B deposition, and restore the structural integrity of chromatin. Our assays show that Spt16-N binds H3–H4 histones primarily through a 1:1 complex with H3–H4 dimers and a 2:1 complex with H3–H4 tetramers (or a 2:2 complex with H3–H4 dimers, assuming that Spt16-N dimerizes). Future structural studies of FACT bound to histones will reveal differences and similarities to chaperones such as Asf1 (40–42) and promise to shed further light on the inner workings of this comprehensive H2A–H2B and H3–H4 histone binding and nucleosome reorganization complex.

Materials and Methods

Protein Expression and Purification.

S. pombe Spt16 N-terminal domain (Spt16-N; residues 1- 442) was cloned into pETM11, providing an N-terminal 6×His tag and tobacco etch virus (TEV) site (leaving an N-terminal overhang of the residues Gly–Met, where Met corresponds to the residue 1 of Spt16). Spt16-N was grown in E. coli BL21 DE3 to OD = 0.6 and induced with 0.2 mM isopropyl β-d-thiogalactoside in TB at 18°C for 16 h. Selenomethionine-labeled protein was expressed in strain B834 (DE3) at 28°C and induced for 18 h with 0.5 mM isopropyl β-d-thiogalactoside in TB with 40 μg/ml seleno-l-methionine. Cells were resuspended in 50 mM NaPi (pH 7.4), 500 mM NaCl, 10 mM imidazole, and 5 mM 2-mercaptoethanol (β-ME), lysed by sonication, and centrifuged at 45,000 × g for 45 min. The supernatant was loaded onto a Co2+ affinity chromatography column (Sigma), washed with 50 mM NaPi, 1 M NaCl, 20 mM imidazole, and 5 mM β-ME, and eluted in the same buffer with 500 mM imidazole. Elutions were concentrated to 10 mg/ml by using an Amicon 10,000 MWCO concentrator. The 6×His tag was cleaved with TEV for 16 h at 4°C. Next, Spt16-N was purified on a Superdex 75 HR16/60 column (GE Healthcare) equilibrated in 50 mM Na Pi (pH 7.4), 500 mM NaCl, and 5 mM β-ME. Fractions were dialyzed against 20 mM Hepes (pH 7.0), 25 mM NaCl, and 3 mM DTT and concentrated to ≈13 mg/ml. Site-specific mutations were introduced by PCR and purified like wild type. Recombinant histones were purified and refolded as described (43).

Crystallization and Data Collection.

Orthorhombic crystals of selenomethionine-labeled Stp16-N (form A; Table S1) were grown at room temperature from hanging drops composed of 1 μl of protein and 1 μl of crystallization buffer (13% [vol/vol] PEG 2000/100 mM Bis-Tris propane, pH 7.0) suspended over 0.5 ml of the latter. Unlabeled protein crystals (form B; Table S1) developed in 20% [vol/vol] PEG 300 and 100 mM Mes (pH 5.5). Crystals were transferred in reservoir solution containing 15% [vol/vol] ethylene glycol and frozen in liquid N2. Multiple-wavelength anomalous dispersion data were collected at beamline PX01 (Swiss Light Source, Villigen, Switzerland) by using the microdiffractometer and a defocused beam. A higher-resolution data set was acquired at beamline BM16 (European Synchrotron Radiation Facility, Grenoble, France). A complete data set for crystal form B was recorded at beamline I04 (Diamond Light Source, Didcot, UK). Data processing and scaling were done with XDS (44).

Structure Determination and Refinement.

Multiple-wavelength anomalous dispersion data were used to locate eight selenium sites with SHELXD (45) that were input into SOLVE and RESOLVE (46) for site refinement, phasing, density modification, and phase extension. Secondary structure elements were identified with BUCCANEER (47). The structure was completed in alternating cycles of model correction in COOT (48) and restrained TLS refinement in Refmac5 (49). The structure of crystal form B was determined by molecular replacement with PHASER (50). Structural visualization was done with POVSCRIPT/POVRAY (51).

ITC.

Binding affinities of wild-type and mutant Spt16-N with N-terminal tails of H4, residues 1–35 (N-acetylated, with a C-terminal Tyr), and H3, residues 1–38 (with a C-terminal Tyr), were determined at 25°C by using ITC (MicroCal). Proteins and peptides were dialyzed against ITC buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 7.9/25 mM NaCl/1 mM EDTA). Injections consisted of 10 μl of peptide (650 μM) into 40 μM protein at 5-min intervals. Data were analyzed by using Origin (version 5.0).

Histone Refolding and Gel Filtration.

Histone refolding was performed as described (43), with modifications: Full-length and globular H3 and H4 were mixed at equimolar ratios to a final concentration of 1 mg/ml and refolded in 150 mM NaCl, 25 mM Tris (pH 7.5), and 5 mM β-ME. Globular H3 and H4 were further diluted into the same buffer containing 50 mM NaCl. Histones and Spt16-N were mixed at equimolar ratios and incubated on ice for 30 min. Proteins were separated on a Superdex 200 10/300 GL column at 150 mM NaCl.

Analytical Ultracentrifugation.

Sedimentation velocity experiments were done at 4°C by using two-channel charcoal centerpieces at 47,000 rpm in a Beckman Optima XL-A centrifuge fitted with a four-hole AN-60 Ti rotor. Samples of Spt16-N (9 μM) and H3–H4 (9 μM) were equilibrated against a buffer containing 150 mM NaCl and 25 mM Tris (pH 7.5) and loaded into a double-sector quartz cell. Sedimentation velocity profiles were collected by monitoring absorbance at 280 nm. Sedimentation coefficient and molecular mass distributions were analyzed by the C(s) method (52). Buffer density and viscosity corrections were made according to published data (53).

GST Pull-Downs.

A total of 40 μl of glutathione Sepharose FF beads (GE Healthcare) were incubated with 50 μg of E. coli-expressed, gel-filtration-purified, GST-fused Spt16-N for 30 min on ice in 150 mM NaCl and 25 mM Tris (pH 7.5). Next, beads were incubated with refolded H2A–H2B and/or H3–H4 at 2-fold excess of histone for 1 h at 4°C. Beads were washed five times with 250 mM NaCl, 25 mM Tris (pH 7.5), and 0.1% Nonidet P-40. The sample was boiled in SDS loading buffer and analyzed by SDS/PAGE. Native Drosophila histones were purified from 0- to 12-h embryos (54).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

We thank K. Luger (Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO) for histone plasmids; G. Stier (EMBL, Heidelberg) for pETM11 vector; staff at beamlines PX01, BM16, and I04 (Diamond, Didcot, UK) for assistance during data collection; and F. Wieland, C. Schultz, T. Gibson, and C. Margulies for comments. This work was supported by the European Molecular Biology Laboratory, the European Union Epigenome Network of Excellence (A.G.L.), European Union Marie Curie Research Training Network Chromatin Plasticity (A.G.L.), and the Peter and Traudl Engelhorn Foundation (M.H.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data deposition: The atomic coordinates have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, www.pdb.org (PDB ID codes 3CB5 and 3CB6).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0712293105/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Reinberg D, Sims RJ., III de FACTo nucleosome dynamics. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:23297–23301. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R600007200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Orphanides G, Wu WH, Lane WS, Hampsey M, Reinberg D. The chromatin-specific transcription elongation factor FACT comprises human SPT16 and SSRP1 proteins. Nature. 1999;400:284–288. doi: 10.1038/22350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brewster NK, Johnston GC, Singer RA. Characterization of the CP complex, an abundant dimer of Cdc68 and Pob3 proteins that regulates yeast transcriptional activation and chromatin repression. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:21972–21979. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.34.21972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Formosa T, et al. Spt16-Pob3 and the HMG protein Nhp6 combine to form the nucleosome-binding factor SPN. EMBO J. 2001;20:3506–3517. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.13.3506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Okuhara K, et al. A DNA unwinding factor involved in DNA replication in cell-free extracts of Xenopus eggs. Curr Biol. 1999;9:341–350. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(99)80160-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lejeune E, et al. The chromatin-remodeling factor FACT contributes to centromeric heterochromatin independently of RNAi. Curr Biol. 2007;17:1219–1224. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.06.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Malone EA, Clark CD, Chiang A, Winston F. Mutations in SPT16/CDC68 suppress cis- and trans-acting mutations that affect promoter function in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1991;11:5710–5717. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.11.5710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miles J, Formosa T. Protein affinity chromatography with purified yeast DNA polymerase alpha detects proteins that bind to DNA polymerase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:1276–1280. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.4.1276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tan BC, Chien CT, Hirose S, Lee SC. Functional cooperation between FACT and MCM helicase facilitates initiation of chromatin DNA replication. EMBO J. 2006;25:3975–3985. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rowley A, Singer RA, Johnston GC. CDC68, a yeast gene that affects regulation of cell proliferation and transcription, encodes a protein with a highly acidic carboxyl terminus. Mol Cell Biol. 1991;11:5718–5726. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.11.5718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Winston F, Chaleff DT, Valent B, Fink GR. Mutations affecting Ty-mediated expression of the HIS4 gene of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 1984;107:179–197. doi: 10.1093/genetics/107.2.179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schlesinger MB, Formosa T. POB3 is required for both transcription and replication in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 2000;155:1593–1606. doi: 10.1093/genetics/155.4.1593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hirschhorn JN, Brown SA, Clark CD, Winston F. Evidence that SNF2/SWI2 and SNF5 activate transcription in yeast by altering chromatin structure. Genes Dev. 1992;6:2288–2298. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.12a.2288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Formosa T, et al. Defects in SPT16 or POB3 (yFACT) in Saccharomyces cerevisiae cause dependence on the Hir/Hpc pathway: Polymerase passage may degrade chromatin structure. Genetics. 2002;162:1557–1571. doi: 10.1093/genetics/162.4.1557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Krogan NJ, et al. RNA polymerase II elongation factors of Saccharomyces cerevisiae: A targeted proteomics approach. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:6979–6992. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.20.6979-6992.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Duroux M, Houben A, Ruzicka K, Friml J, Grasser KD. The chromatin remodelling complex FACT associates with actively transcribed regions of the Arabidopsis genome. Plant J. 2004;40:660–671. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2004.02242.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim M, Ahn SH, Krogan NJ, Greenblatt JF, Buratowski S. Transitions in RNA polymerase II elongation complexes at the 3′ ends of genes. EMBO J. 2004;23:354–364. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pokholok DK, Hannett NM, Young RA. Exchange of RNA polymerase II initiation and elongation factors during gene expression in vivo. Mol Cell. 2002;9:799–809. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00502-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Saunders A, et al. Tracking FACT and the RNA polymerase II elongation complex through chromatin in vivo. Science. 2003;301:1094–1096. doi: 10.1126/science.1085712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Belotserkovskaya R, et al. FACT facilitates transcription-dependent nucleosome alteration. Science. 2003;301:1090–1093. doi: 10.1126/science.1085703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.O'Donnell AF, et al. Domain organization of the yeast histone chaperone FACT: The conserved N-terminal domain of FACT subunit Spt16 mediates recovery from replication stress. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:5894–5906. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.De Koning L, Corpet A, Haber JE, Almouzni G. Histone chaperones: An escort network regulating histone traffic. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2007;14:997–1007. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Allain FH, et al. Solution structure of the HMG protein NHP6A and its interaction with DNA reveals the structural determinants for non-sequence-specific binding. EMBO J. 1999;18:2563–2579. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.9.2563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.VanDemark AP, et al. The structure of the yFACT Pob3-M domain, its interaction with the DNA replication factor RPA, and a potential role in nucleosome deposition. Mol Cell. 2006;22:363–374. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Angelov D, et al. Nucleolin is a histone chaperone with FACT-like activity and assists remodeling of nucleosomes. EMBO J. 2006;25:1669–1679. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mousson F, et al. Structural basis for the interaction of Asf1 with histone H3 and its functional implications. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:5975–5980. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500149102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Park YJ, Chodaparambil JV, Bao Y, McBryant SJ, Luger K. Nucleosome assembly protein 1 exchanges histone H2A-H2B dimers and assists nucleosome sliding. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:1817–1825. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411347200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aravind L, Koonin EV. Eukaryotic transcription regulators derive from ancient enzymatic domains. Curr Biol. 1998;8:R111–R113. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(98)70982-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.VanDemark AP, et al. Structural and functional analysis of the Spt16p N-terminal domain reveals overlapping roles of yFACT subunits. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:5058–5068. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M708682200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lowther WT, Matthews BW. Metalloaminopeptidases: Common functional themes in disparate structural surroundings. Chem Rev. 2002;102:4581–4608. doi: 10.1021/cr0101757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maher MJ, et al. Structure of the prolidase from Pyrococcus furiosus. Biochemistry. 2004;43:2771–2783. doi: 10.1021/bi0356451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Coll M, et al. Enzymatic mechanism of creatine amidinohydrolase as deduced from crystal structures. J Mol Biol. 1990;214:597–610. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(90)90201-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Banks DD, Gloss LM. Equilibrium folding of the core histones: The H3–H4 tetramer is less stable than the H2A-H2B dimer. Biochemistry. 2003;42:6827–6839. doi: 10.1021/bi026957r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jacobson RH, Ladurner AG, King DS, Tjian R. Structure and function of a human TAFII250 double bromodomain module. Science. 2000;288:1422–1425. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5470.1422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Strahl BD, Allis CD. The language of covalent histone modifications. Nature. 2000;403:41–45. doi: 10.1038/47412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Georgel PT, Tsukiyama T, Wu C. Role of histone tails in nucleosome remodeling by Drosophila NURF. EMBO J. 1997;16:4717–4726. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.15.4717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Garcia BA, et al. Organismal differences in post-translational modifications in histones H3 and H4. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:7641–7655. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M607900200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kowalinski E, et al. The crystal structure of Ebp1 reveals a methionine aminopeptidase fold as binding platform for multiple interactions. FEBS Lett. 2007;581:4450–4454. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Monie TP, et al. Structural insights into the transcriptional and translational roles of Ebp1. EMBO J. 2007;26:3936–3944. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Natsume R, et al. Structure and function of the histone chaperone CIA/ASF1 complexed with histones H3 and H4. Nature. 2007;446:338–341. doi: 10.1038/nature05613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Antczak AJ, Tsubota T, Kaufman PD, Berger JM. Structure of the yeast histone H3-ASF1 interaction: Implications for chaperone mechanism, species-specific interactions, and epigenetics. BMC Struct Biol. 2006;6:26. doi: 10.1186/1472-6807-6-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.English CM, Adkins MW, Carson JJ, Churchill ME, Tyler JK. Structural basis for the histone chaperone activity of Asf1. Cell. 2006;127:495–508. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.08.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dyer PN, et al. Reconstitution of nucleosome core particles from recombinant histones and DNA. Methods Enzymol. 2004;375:23–44. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(03)75002-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kabsch W. Automatic processing of rotation diffraction data from crystals of initially unknown symmetry and cell constants. J Appl Crystallogr. 1993;26:795–800. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schneider TR, Sheldrick GM. Substructure solution with SHELXD. Acta Crystallogr D. 2002;58:1772–1779. doi: 10.1107/s0907444902011678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Terwilliger TC. Maximum-likelihood density modification. Acta Crystallogr D. 2000;56:965–972. doi: 10.1107/S0907444900005072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cowtan K. The Buccaneer software for automated model building. 1. Tracing protein chains. Acta Crystallogr D. 2006;62:1002–1011. doi: 10.1107/S0907444906022116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Emsley P, Cowtan K. Coot: Model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr D. 2004;60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Murshudov GN, Vagin AA, Dodson EJ. Refinement of macromolecular structures by the maximum-likelihood method. Acta Crystallogr D. 1997;53:240–255. doi: 10.1107/S0907444996012255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.McCoy AJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Storoni LC, Read RJ. Likelihood-enhanced fast translation functions. Acta Crystallogr D. 2005;61:458–464. doi: 10.1107/S0907444905001617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fenn TD, Ringe D, Petsko GA. POVScript+: A program for model and data visualization using persistence of vision ray-tracing. J Appl Crystallogr. 2003;36:944–947. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schuck P. Size-distribution analysis of macromolecules by sedimentation velocity ultracentrifugation and lamm equation modeling. Biophys J. 2000;78:1606–1619. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76713-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Laue TM, Shah BD, Ridgeway TM, Pelletier SL. In: Analytical Ultracentrifugation in Biochemistry and Polymer Science. Harding SE, Rowe AJ, Horton JC, editors. Cambridge, UK: Royal Soc of Chemistry; 1992. pp. 90–125. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ausio J, van Holde KE. Histone hyperacetylation: Its effects on nucleosome conformation and stability. Biochemistry. 1986;25:1421–1428. doi: 10.1021/bi00354a035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Holm L, Sander C. Protein structure comparison by alignment of distance matrices. J Mol Biol. 1993;233:123–138. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.