Abstract

Background and purpose:

M2-type pyruvate kinase (M2PK) was found to interact directly with the ‘ITAM' region of the γ chain of the high-affinity IgE receptor (FcɛRI). Our hypothesis was that mast cell degranulation might require the FcɛRI-mediated inhibition of M2PK activity.

Experimental approach:

In rat basophilic leukaemia (RBL-2H3) cells, the effects of directly inhibiting M2PK or preventing the FcɛRI-mediated inhibition of M2PK (disinhibition) on degranulation was measured by hexosaminidase release. Effects of blocking the FcɛRI-mediated inhibition of M2PK was also assessed in vivo in a mouse model of allergen-induced airway hyper-responsiveness.

Key results:

Activation of FcɛRI in RBL-2H3 cells caused the rapid phosphorylation of tyrosine residues in M2PK, associated with a decrease in M2PK enzymatic activity. There was an inverse correlation between M2PK activity and mast cell degranulation. FcɛRI-mediated inhibition of M2PK involved Src kinase, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase, PKC and calcium. Direct inhibition of M2PK potentiated FcɛRI-mediated degranulation and prevention of the FcɛRI-mediated inhibition of M2PK attenuated mast cell degranulation. Transfection of RBL-2H3 cells with M1PK which prevents FcɛRI-induced inhibition of M2PK, markedly reduced their degranulation and exogenous M1PK (i.p.) inhibited ovalbumin-induced airway hyper-responsiveness in vivo.

Conclusions and implications:

We have identified a new control point and a novel biochemical pathway in the process of mast cell degranulation. Our study suggests that the FcɛRI-mediated inhibition of M2PK is a crucial step in responses to allergens. Moreover, the manipulation of glycolytic processes and intermediates could provide novel strategies for the treatment of allergic diseases.

Keywords: mast cells, FcɛRI, M2-type pyruvate kinase, allergy, glycolysis

Introduction

Although there is no direct evidence of an association between glycolytic enzymes and allergic responsiveness, several studies suggest a link between glucose metabolism and allergies. For example, the concentrations of pyruvate (Pleshkova and Tsvetkova, 1978) and ATP (Norn et al., 1976) are lower in mast cells after antigen challenge. Histamine release is inhibited by the non-metabolizable glucose analogue, 2-deoxyglucose (Chakravarty, 1967) and by glycogenolytic intermediates (Okazaki et al., 1975). Moreover, lower pyruvate kinase (PK) activity has been reported in patients with atopic dermatitis (Miklaszewska et al., 1989) and eczema (Buchtova and Cech, 1982). However, the molecular details of the relationship between these two apparently distinct cellular processes, that is, allergic and glycolytic reactions, remain unknown.

The high-affinity IgE receptor (FcɛRI) is a hetero-tetrameric receptor composed of four subunits: two disulphide-linked γ-subunits that transduce signals generated by antigen binding; a β-subunit that amplifies γ-subunit signaling and an α-subunit that binds IgE (Blank et al., 1989). Antigenic crosslinking of FcɛRIs initiates a series of tyrosine phosphorylation events (Nadler et al., 2000). These phosphorylation events involve immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motifs (ITAMs) (Reth, 1989) of the β- and γ-chains. The phosphorylated ITAMs then serve as Src homology 2 domain-docking sites for protein tyrosine kinases (PTKs), such as Lyn (Eiseman and Bolen, 1992), Syk (Benhamou et al., 1993) and Fyn (Parravicini et al., 2002), at the tyrosine-phosphorylation consensus sequences, D/E-XX-YXXL-X7−11-YXXL-L/I.

The four known isozymes of PK (L, R, M1 and M2) regulate a terminal step in glycolysis by catalysing the transfer of a high-energy phosphate group from phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP) to ADP, which results in the formation of pyruvate and ATP (Cardenas, 1982; Imamura and Tanaka, 1982). The two M-type PKs (M1PK and M2PK) are produced by alternative splicing and are expressed in different tissues (Noguchi et al., 1986; Takenaka et al., 1989). M2PK is specifically expressed in mast cells (Pemberton et al., 2006) and is differentially regulated by tyrosine kinases (for a review, see Eigenbrodt et al., 1992).

The γ-chain of FcɛRI and the M-type PK have been reported to interact (Oak et al., 1999), providing the first direct biochemical evidence of a relationship between glycolytic processes and allergic reactions. A series of studies focusing on the linkage between glycolytic processes and allergic reactions were conducted to determine the functional significance of the interaction between M2PK and FcɛRI. The data demonstrated the following: (1) the ITAM of the FcɛRI-γ-chain binds to M2PK, and the resulting FcɛRI-mediated decrease in M2PK activity is essential for mast cell degranulation; (2) Src kinase, phosphoinositide-3 kinase (PI-3K), protein kinase C (PKC) and calcium are involved in the FcɛRI-mediated inhibition of M2PK and (3) manipulation of glycolytic processes may provide a novel strategy for the treatment of allergic diseases.

Materials and methods

Yeast strains and cell cultures

The Saccharomyces cerevisiae strain used (L40) was kindly provided by Dr Hollenberg (Oregon Health Sciences, USA) (Hollenberg et al., 1995). Rat basophilic leukaemia (RBL-2H3) cells were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (Rockville, MD, USA). The cells were cultured in Eagle's Minimum Essential Medium (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY, USA) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (Hyclone, Logan, UT, USA) and 10 μg mL−1 gentamicin (Sigma Chemical Co., St Louis, MO, USA) at 37 °C with 5% CO2 in an air atmosphere. The 2,4-dinitrophenyl (DNP)-specific mouse monoclonal IgE was obtained from the hybridoma cell line IGEL b4. The transfections were performed on a ∼70–80% confluent monolayer in 100-mm dishes, using either calcium phosphate co-precipitation methods or lipofectamine (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA).

DNA constructs

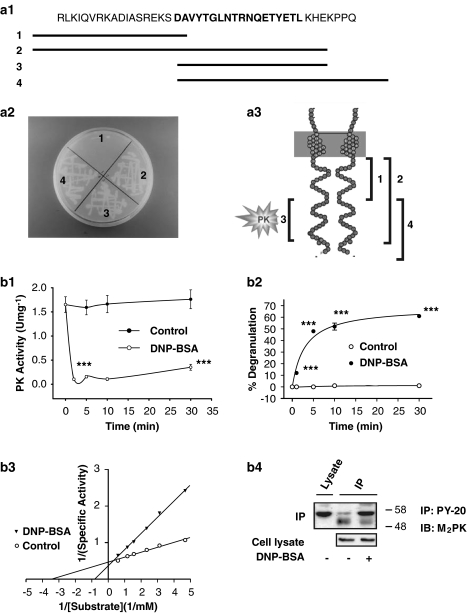

The yeast vectors (pLexA, pVP16) were kindly provided by Dr Hollenberg (Oregon Health Sciences) (Hollenberg et al., 1995). To identify the M2PK-binding site on the FcɛRI-γ-chain, four different regions around the ITAM (Figure 1a) were amplified by PCR, restricted with EcoRI and subcloned into pLexA. M1PK and M2PK were tagged with the M2-FLAG epitope at the N-terminus, with the eight-residue sequence of the epitope (DYKDDDDA) inserted after Met1 in pcDNA3.1 Zeo(+) (EcoRI/XbaI). These Flag-tagged constructs were also green fluorescence protein (GFP)-tagged on the N-terminal tail by subcloning them into the EcoRI/BamHI sites of the pEGFP-C2 vector (Clontech, Mountain View, CA, USA).

Figure 1.

Regulation of M2PK activity through interaction with the γ-chain of FcɛRI. (a) Localization of the specific interaction site of the γ-chain with M2PK by yeast two-hybrid assay. (a1) Representative constructs of the cytoplasmic part of the γ-chain. The bold characters represent the ITAM-binding domain. (a2) The four DNA fragments shown in panel (a1) were inserted into pLexA, a yeast expression vector (the bait construct), and transformed into S. cerevisiae, along with M2PK subcloned into pVP16 (prey plasmid). The yeast was grown at 30 °C for 4 days. Numbers 1–4 correspond to the respective pLex-A constructs. (a3) Diagrammatic representation of the γ-chain that interacts with M2PK. (b) Changes in enzymatic properties and tyrosine phosphorylation of M2PK following activation of FcɛRI. (b1) RBL-2H3 cells were treated with 0.5 μg mL−1 IgE overnight, treated with 100 ng mL−1 DNP-BSA for 5 min and assessed for PK activity. ***P<0.001 compared with the control group (PIPES buffer). (b2) Degranulation in RBL-2H3 cells was measure by the amount of hexosaminidase released. This release was calculated by subtracting spontaneous release before cell stimulation from that after the cells had been stimulated with DNP-BSA (1 μg mL−1, 10 min); spontaneous release was defined as hexosaminidase activity measured in the supernatant in the absence of antigenic stimulation. Each data point represents the mean±s.e.mean. Student's t-test was used for statistical analysis. ***P<0.001 compared with the control group (PIPES buffer). (b3) PK activity was measured at substrate (PEP) concentrations ranging from 0.2 and 1.7 mM. (b4) Phosphorylation studies for M2PK. RBL-2H3 cells were treated overnight with serum-free Eagle's Minimum Essential Medium and then stimulated with DNP-BSA (100 ng mL−1) for 1 min. The cell lysate was centrifuged and the supernatant was immunoprecipitated with phosphotyrosine antibodies conjugated to agarose beads. The immunoblots were probed with antibodies to M-type PK (1:3000 dilution). The data shows representative results from three independent experiments with similar outcomes. IP=immunoprecipitation, IB=immunoblotting, PY-20=phosphotyrosine antibodies. BSA, bovine serum albumin; FcɛRI, high-affinity IgE receptor; ITAM, immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif; M2PK, M2-type pyruvate kinase; PEP, phosphoenolpyruvate; PK, pyruvate kinase.

Degranulation assays

The degranulation assays were performed according to the procedure reported elsewhere (Oak et al., 1999). RBL-2H3 cells were treated with anti-DNP specific mouse IgE (0.5 μg mL−1) overnight and on the next morning, cells were washed and preincubated in PIPES buffer (pH 7.2, 119 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 0.4 mM MgCl2, 25 mM PIPES, 40 mM NaOH, 5.6 mM glucose, 1 mM CaCl2, 0.1% bovine serum albumin (BSA)) for 10 min at 37 °C. The cells were treated with the antigen (DNP-BSA, 1 μg mL−1) for 10 min at 37 °C. The supernatants were transferred to 96-well plates and incubated with hexosaminidase substrate (1 mM p-nitrophenyl-N-acetyl-D-glucosaminide) for 1 h. A stop solution (0.1 M Na2CO3/NaHCO3) was added and absorbance at 405 nm was measured with an ELISA reader.

PK assay and kinetics

RBL-2H3 cells were plated at a density of 3 × 106 cells per 100-mm dish in a medium containing 0.5 μg mL−1 monoclonal mouse IgE and cultured overnight. The cells were washed twice with PIPES buffer and treated with the antigen (DNP-BSA, 100 ng mL−1). The reaction was quenched on ice by removing the PIPES buffer, and the cells were harvested in PIPES buffer containing 0.5% NP-40, freeze-thawed three times and centrifuged at 48 000 g for 20 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was used as the enzyme source. The reaction mixture (31 mM potassium phosphate, 0.43 mM phospho(enol)pyruvate, 0.11 mM β-nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide reduced form, 6.7 mM magnesium sulphate, 1.3 mM adenosine 5′-diphosphate, 20 U of lactic dehydrogenase in 3 mL) was equilibrated at 37 °C and the reaction was started by adding 100 μL of the enzyme source. Decrease in absorbance at 340 nm was measured for 2 min. The protein concentration of each sample was measured and the activity of the PK was normalized to protein level.

To measure kinetics, substrate concentration was varied from 0.2 to 1.7 mM and activity was measured 5 min after stimulation. The Km value and the maximum activity (Vmax) were calculated according to the Michaelis–Menten equation.

Phosphorylation studies using phosphorylated amino acid-specific antibodies

RBL-2H3 cells were treated with IgE overnight and washed with the PIPES buffer containing phosphatase inhibitors (1 mM EDTA, 1 mM sodium orthovanadate, 5 mM sodium fluoride) and treated with DNP-BSA (100 ng mL−1) for 1 min. The cells were collected in lysis buffer (200 mM boric acid, 160 mM NaCl, 0.3% Triton X-100, 1% BSA, pH 8.0, 10 μg mL−1 leupeptin and aprotinin, 1 mM phenylmethylsulphonyl fluoride, 1 mM sodium orthovanadate and 5 mM sodium fluoride), freeze-thawed twice and centrifuged at 48 000 g for 30 min. The postnuclear supernatants were immunoprecipitated with the anti-phosphotyrosine, anti-phosphoserine or anti-phosphothreonine antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, USA) or Sigma Chemical Co). The beads were boiled for 5 min in Laemmli buffer and analysed by immunoblotting with antibodies for M-type PK (Noguchi et al., 1986).

Measurement of cellular fructose-1,6-bisphosphate level

The RBL-2H3 cells were seeded at a density of 2 × 106 cells per 150-mm plate and treated overnight with 0.5 μg mL−1 anti-DNP specific mouse IgE. On the next day, cells were treated with 100 ng mL−1 DNP-BSA for 4 h, extracted with 0.1 mM TEA buffer (triethanolamine acetate buffer, pH 7.6) and centrifuged. The supernatant was then mixed with the enzyme reaction solution containing 5 U of glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase and 0.01 mM NADH). After preincubation at 37 °C for 2 min, 5 U of triose phosphate isomerase and 2 U of aldolase were added and incubation was performed at 37 °C for 3 min. Absorbance was measured at 340 nm and normalized to the protein content in the sample.

Animals

All animal procedures and experiments were conducted in accordance with the NIH guidelines for the care and use of animals and with approval from the Duke University Animal Care and Use Committee. Male and female C57Bl/6J mice (The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME, USA) were used for all experiments at 13–15 weeks of age.

Immunization and airway challenge

Mice were immunized intraperitoneally on days 0, 7 and 14 with 10 μg Grade-V ovalbumin (Sigma/Aldrich Chemical Co., St Louis, MO, USA) adsorbed to 200 μg of alum adjuvant (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA) diluted in saline. Secondary challenge consisted of a 60-min exposure to an aerosol of 6% (w/v) ovalbumin in saline, on day 21. All mice were exposed to ovalbumin aerosol in a 60-L Hinners-style exposure chamber connected to the outlet of a six-jet atomizer that delivered an aerosol of particles with a mean diameter of 0.3 μm (TSI Instruments, St Paul, MN, USA). Sham-treated mice received alum intraperitoneally and were exposed to saline aerosol according to the protocol above. Within 1–6 h after ovalbumin aerosol challenge, mice were tested for airway responsiveness to methacholine (MCh).

Airway responsiveness

On the same day as ovalbumin (or saline) aerosol challenge, airway responsiveness to MCh was measured as previously described (Walker et al., 1999). In brief, mice were anaesthetized with an intraperitoneal injection of pentobarbital sodium (60 mg kg−1) diluted 50% with saline and surgically prepared with a tracheal cannula and a jugular vein catheter. Mice were given a pre-experiment dose of pentobarbital sodium (6 mg kg−1) and paralysed with doxacurium chloride (0.25 mg kg−1). They were ventilated with 100% oxygen at a constant volume of 8–10 mL kg−1 and a frequency of 125 breaths per minute. These ventilator settings resulted in an average resting peak airway pressure of 7.8±0.2 cm H2O and were previously shown to provide normal arterial blood gases. Once paralysed, heart rate monitored by ECG was used to ensure adequate depth of anaesthesia. Measurement of airway pressure was made at a side port of the tracheal cannula connected to a Validyne differential pressure transducer. The time-integrated change in peak airway pressure (airway pressure time index) (Levitt and Mitzner, 1988) was calculated for a 30-s period, beginning immediately after MCh injection via jugular vein.

Data analysis

Results shown are means±s.e.mean, unless otherwise stated. Student's t-test was used for statistical analysis, unless otherwise specified.

Materials

Anti-phosphotyrosine (PY-20) and anti-Syk antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Anti-rabbit or anti-mouse antibodies conjugated to alkaline phosphatase were purchased from the Sigma Chemical Co. Anti-mouse IgE antibodies were obtained from either Pharminogen (San Diego, CA, USA) or Calbiochem (San Diego, CA, USA). 2-(4-Morpholinyl)-8-phenyl-4H-1-benzopiran-4-one (wortmannin), phorbol-12-myristate-13-acetate (PMA), 3,4,3′,5′-tetrahydroxy-trans-stilbene (piceatannol) and 4-amino-5-(4-chlorophenyl)-7-(t-butyl) pyrazolo [3,4-d] pyrimidine (PP2) were purchased from the Sigma Chemical Co. 12-(2-Cyanoethyl)-6,7,12,13-tetrahydro-13-methyl-5-oxo-5H-indolo [2-3a] pyrrolo [3,4-c]-carbazol (Gö6976) and 3-[1-(3-dimethylamino-propyl)-5-methoxy-1H-indol-3-yl] 4-(1H-indol-3-yl)pyrrolidine-2,5-dione (Gö6983) were purchased from the Calbiochem.

Results

M2-type PK interacts with the ITAM of FcɛRI-γ-chain

Previous studies reported an interaction between M-type PK and the γ-chain of FcɛRI in RBL-2H3 cells using an yeast two-hybrid assay, a glutathione-S-transferase pull-down assay and by immunoprecipitation (Oak et al., 1999). M2PK contains Src homology 2 domains and the FcɛRI-γ-chain contains ITAM (Figure 1a1), which is essential for binding to proteins that contain Src homology domains (Reth, 1989). An yeast two-hybrid assay using four regions in the FcɛRI-γ-chain around the ITAM was used to identify the specific subunit-binding domain for M2PK. M2PK interacted with three ITAM-containing peptides of different lengths (denoted 2, 3 and 4) (Figures 1a2 and 1a3), which suggests that the ITAM consensus sequence in the γ-chain, DAVYTGLNTRNQETYETL, is sufficient for binding to M2PK.

Activation of FcɛRI results in reduced enzymatic activity of M2-type PK accompanying phosphorylation of tyrosine residues

FcɛRI-mediated regulation of M2PK was examined by correlating the level of mast cell degranulation, as measured by hexosaminidase release (Schwartz et al., 1979), with cellular M2PK activity. The application of the antigen DNP-BSA resulted in an immediate and sustained decrease in PK activity. Enzyme activity decreased by 90% within 2 min and recovered slowly thereafter (Figure 1b1). Degranulation lagged behind the decrease in PK activity and reached a plateau between 5 and 10 min (Figure 1b2). This suggests that the rapid decrease in PK activity might be a process more proximal to FcɛRI activation than degranulation.

The changes in M2PK activity and the degree of M2PK tyrosine phosphorylation were previously observed in cells stimulated with various growth factors (Presek et al., 1988). Accordingly, in this study, we examined changes in M2PK as a result of antigenic crosslinking of FcɛRI. Figure 1b3 shows the decrease in the affinity of M2PK for PEP upon aggregation of FcɛRI and the concurrent increase of Km from 0.29 to 1.21 mM. However, maximum velocity (Vmax) decreased only slightly from 10.9 to 8.6 U mg−1 protein.

The aggregation of FcɛRI resulted in phosphorylation of M2PK on tyrosine residues (Figure 1b4), although M2PK was constitutively phosphorylated. These results suggest that the FcɛRI-mediated tyrosine phosphorylation of M2PK can trigger the inhibition of M2PK.

Considering that protein interaction was observed between M2PK and FcɛRI in resting cells, and even in glutathione-S-transferase pull-down assays (Oak et al., 1999), it is unlikely that tyrosine phosphorylation of the γ-chain of FcɛRI is essential for interaction between the two proteins. In addition, intracellular translocation of M2PK was not observed when RBL-2H3 cells that had been transfected with GFP-tagged M2PK were stimulated with antigen (data not shown).

Src and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase are involved in the FcɛRI-mediated regulation of M2-type PK

The Src family of PTKs, Lyn and Fyn, are FcɛRI-signalling proteins that bind PTK-phosphorylated ITAM consensus sequences as a result of FcɛRI activation. This recruitment enables them to phosphorylate other ITAM-binding proteins (for a review, see Rivera, 2002). FcɛRI-mediated tyrosine phosphorylation (Figure 2a1, compare lanes 3 and 4) and FcɛRI-mediated inhibition of M2PK activity were both prevented (disinhibition) (Figure 2a2) when RBL-2H3 cells were pretreated with 10 μM PP2, a selective Src inhibitor (Salazar and Rozengurt, 1999). Mast cell degranulation was also inhibited by PP2 in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 2b1). PP2 has been used for to elucidate signalling pathways activated by FcɛRI in mast cells (Sulimenko et al., 2006).

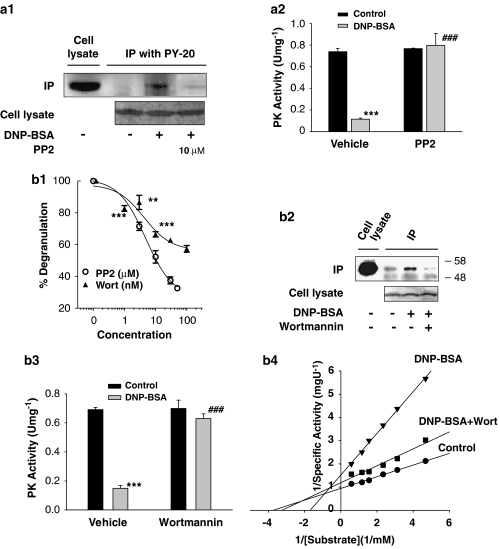

Figure 2.

Involvement of Src protein tyrosine kinases and phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase in FcɛRI-mediated inhibition of M2PK. (a and b) Effects of inhibitors of Src kinase or PI-3K on mast cell degranulation and FcɛRI-mediated biochemical changes of M2PK. (a1) RBL-2H3 cells were treated overnight with serum-free Eagle's Minimum Essential Medium followed by treatment with 10 μM PP2 for 20 min. The cells were then stimulated with DNP-BSA (100 ng mL−1) for 1 min. The data presented are representative of three independent experiments with similar outcomes. (a2) RBL-2H3 cells were treated with 10 μM PP2 for 20 min and then stimulated with DNP-BSA for 5 min. ***P<0.001 versus control group (PIPES buffer); ###P<0.001 versus the vehicle (DMSO)/DNP-BSA-treated group. (b1) Effects of PP2 and wortmannin (Wort) on the mast cell degranulation. RBL-2H3 cells were treated with 3–50 μM of PP2 or 1–100 nM wortmannin for 20 min and the level of degranulation was then measured. **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 versus the corresponding vehicle (DMSO)-treated group. (b2) Effects of wortmannin on FcɛRI-mediated tyrosine phosphorylation of M2PK. RBL-2H3 cells were treated with 30 nM wortmannin for 20 min and then stimulated with DNP-BSA for 5 min. (b3) Effects of wortmannin on FcɛRI-mediated inhibition of M2PK. RBL-2H3 cells were treated with 20 nM wortmannin for 20 min cells were then stimulated with 100 ng mL−1 DNP-BSA for 5 min. ***P<0.001 compared with the vehicle/control group; ###P<0.001 compared with the vehicle/DNP-BSA-treated group. (b4) Effects of wortmannin (Wort) on the enzyme kinetics of M2PK. Cells were treated with 30 nM wortmannin for 20 min and enzyme kinetics were analysed as described in Figure 1b3. BSA, bovine serum albumin; DMSO, dimethylsulphoxide; FcɛRI, high-affinity IgE receptor; M2PK, M2-type pyruvate kinase; PI-3K, phosphoinositide-3 kinase; RBL-2H3, rat basophilic leukaemia cells.

FcɛRI-mediated M2PK regulation also involves PI-3K, which plays an important role in regulating mast cell degranulation (Yano et al., 1993), as well as in insulin-mediated regulation of the enzymatic activity of L-type PKs (Carrillo et al., 2001). As reported previously (Yano et al., 1993), pretreating RBL-2H3 cells with 30 nM wortmannin, a selective PI-3K inhibitor, for 15 min blocked FcɛRI-mediated degranulation (Figure 2b1) and tyrosine phosphorylation of M2PK (Figure 2b2, compare lane 3 and lane 4), and at the same time disinhibited antigen-induced inhibition of M2PK (Figure 2b3). The FcɛRI-mediated increase in the Km for PEP (from 0.27 to 0.59 mM) was mainly prevented by pretreatment with wortmannin (up to 0.30 mM) (Figure 2b4).

Role of PKC in the FcɛRI-mediated regulation of M2-type PK

Both calcium flux and PKC activation are essential for mast cell degranulation (Ozawa et al., 1993). Recent studies suggest that calcium flux and PKC activation are controlled by different Src-family PTKs, Lyn and Fyn, respectively (Nadler and Kinet, 2002; Parravicini et al., 2002). Addition of PKC inhibitors Gö6976 and Gö6983 (Qatsha et al., 1993; Stempka et al., 1997), or depletion of cellular PKC, as a result of overnight treatment with PMA, inhibited mast cell degranulation (Figure 3a) and disinhibited the FcɛRI-mediated inhibition of M2PK (Figure 3b), suggesting that PKCs are involved in the FcɛRI-mediated regulation of M2PK.

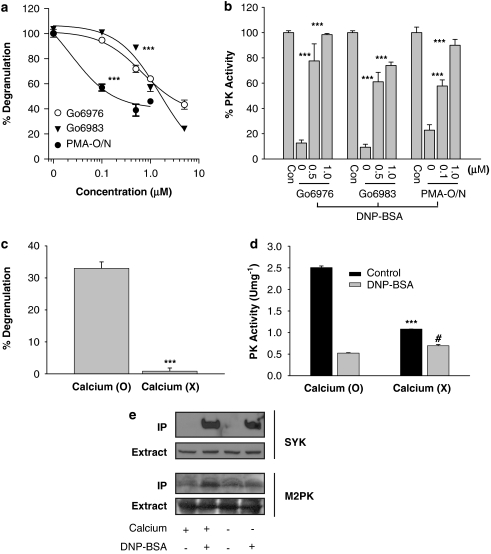

Figure 3.

Roles of PKC and calcium on FcɛRI-mediated regulation of M2PK. (a) Effects of the PKC inhibitors or depletion of cellular PKC on FcɛRI-mediated mast cell degranulation. RBL-2H3 cells were treated with either Gö6973 or Gö6983 for 20 min, or with 1 μM PMA overnight, then stimulated with 1 μg mL−1 DNP-BSA for 10 min. ***P<0.001 compared with the vehicle-treated group (DMSO). The inhibitions of mast degranulation by PKC inhibitors or PMA treatment were statistically significant (P<0.001) compared with the vehicle-treated group at all the concentrations higher than 0.5 μM PKC inhibitors and 0.1 μM PMA. (b) Effects of the PKC inhibitors or depletion of cellular PKC on the FcɛRI-mediated inhibition of M2 type PK activity. The cells were treated with increasing concentrations of Gö6973 or Gö6983 for 20 min or with 1 μM PMA overnight, and then stimulated with 100 ng mL−1 DNP-BSA for 5 min. PK activity was measured as described under Materials and methods. ***P<0.001 compared with the control (DMSO/DNP-BSA) group. (c) Effects of calcium on mast cell degranulation. For the calcium-free experimental group (shown as X), a PIPES buffer without CaCl2 was used. Cells were stimulated with 1 μg mL−1 DNP-BSA for 10 min. ***P<0.001 compared with the calcium (O) group. (d) Effects of calcium on the enzymatic activities of M2PK. Cells were stimulated with 100 ng mL−1 DNP-BSA for 5 min. ***P<0.001 compared with the calcium (O)/control group; #P<0.1 compared with calcium (O)/DNP-BSA group. (e) Effects of calcium on the tyrosine phosphorylation of Syk and M2PK. The RBL-2H3 cells were treated with 100 ng mL−1 DNP-BSA for 1 min in the presence or absence of calcium. The cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with the PY-20 antibody conjugated to agarose beads and the immunoprecipitates were analysed on sodium dodecyl sulphate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. The blots were probed with the antibodies to Syk and M-type PK at 1:1000 and 3000 dilutions, respectively. Data represent results from two independent experiments with similar outcomes. BSA, bovine serum albumin; DMSO, dimethylsulphoxide; FcɛRI, high-affinity IgE receptor; M2PK, M2-type pyruvate kinase; PKC, protein kinase C; PMA, phorbol myristate acetate; RBL-2H3, rat basophilic leukaemia cells.

The FcɛRI-mediated mast cell degranulation (Figure 3c), the basal enzymatic activity as well as antigen-induced decrease in enzymatic activity (Figure 3d) were markedly decreased in the absence of calcium. In accordance with this, FcɛRI-mediated tyrosine phosphorylation of M2PK markedly decreased in the absence of calcium (Figure 3e). In contrast, FcɛRI-mediated tyrosine phosphorylation of Syk, a positive control, was clearly calcium-independent.

FcɛRI-mediated inhibition of M2-type PK is required for mast cell degranulation

The results from Figures 1, 2 and 3 show that aggregation of FcɛRI induced mast cell degranulation and inhibition of cellular PK activity The FcɛRI-mediated inhibition of M2PK activity preceded mast cell degranulation (Figure 1b). Therefore, we hypothesized that mast cell degranulation might be causally linked to FcɛRI-mediated inhibition of M2PK activity. This hypothesis was tested by directly inhibiting M2PK or by preventing the FcɛRI-mediated inhibition of M2PK (disinhibition) and then observing the effects on mast cell degranulation.

FcɛRI-mediated degranulation was significantly enhanced when cellular PK activity was reduced by treating RBL-2H3 cells with PK inhibitors such as pyruvate, which is a negative feedback inhibitor of PK (Figures 4a1 and a2). A relatively non-specific PK inhibitor, NaF (Guminska and Sterkowicz, 1976), also gave similar results (Figure 4b). On the other hand, FcɛRI-mediated degranulation was decreased significantly (Figure 4c) when GFP-M1PK was stably transfected into RBL-2H3 cells (Figure 4d). It was reported that M1PK is not regulated by PTKs (Presek et al., 1988), and M1PK is expected to remain active despite activation of FcɛRI, circumventing the FcɛRI-mediated decrease in PK activity by forming a short circuit between PEP and pyruvate.

Figure 4.

Relationship between the FcɛRI-mediated inhibition of M2PK and mast cell degranulation. (a) Effects of exogenously added pyruvate, an allosteric inhibitor of PK, on mast cell degranulation. (a1) RBL-2H3 cells were treated with 1 mM pyruvate for 20 min, followed by 1 μg mL−1 DNP-BSA treatment for 5 min and PK activity was then measured. ***P<0.001 versus the control group. (a2) RBL-2H3 cells were treated with increasing concentrations of pyruvate and then stimulated with 1 μg mL−1 DNP-BSA for 10 min. The control is the release of hexosaminidase induced by DNP-BSA in the absence of added pyruvate. ***P<0.001 versus the ‘no pyruvate added' group. (b) Effects of NaF, a moderately selective PK inhibitor, on RBL cell degranulation. The RBL-2H3 cells were treated with 10 mM NaF for 20 min, followed by 100 ng mL−1 DNP-BSA treatment for 5 min; then PK activity was measured (left panel). ***P<0.001 compared with the control (NaF(−)) group. For degranulation assay, RBL-2H3 cells were treated with 1 μg mL−1 DNP-BSA for 10 min and then mast cell degranulation was measured (right panel). ***P<0.001 compared with the control (NaF(−)) group. (c) Effects of exogenous M1PK on mast cell degranulation. (c1) Wild-type RBL-2H3 cells (WT) or RBL-2H3 cells stably expressing the GFP-encoding vector or GFP-M1PK were used. ***P<0.001 versus the GFP group. (c2) Cell lysates (20 μg of protein) from each cell type were analysed by dodecyl sulphate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and blotted with antibodies for M-type PK. BSA, bovine serum albumin; GFP, green fluorescence protein; M1PK, M1-type pyruvate kinase; M2PK, M2-type pyruvate kinase; PK, pyruvate kinase; RBL-2H3, rat basophilic leukaemia cells.

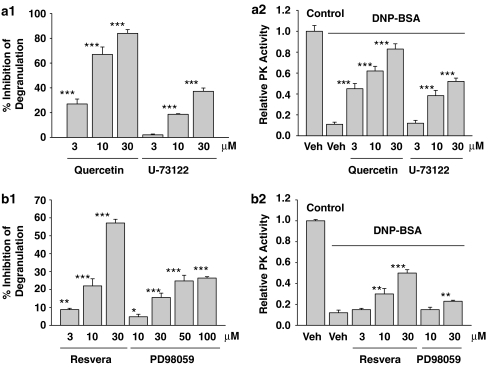

This hypothesis was further tested using chemicals previously reported to inhibit mast cell degranulation by modulating the signalling pathways of FcɛRI. The extent of the inhibition of mast cell degranulation was proportional to the disinhibition of FcɛRI-mediated inhibition of M2PK for quercetin (Middleton et al., 1981; Senyshyn et al., 1998) and U-73122 (a phopsholipase C inhibitor, which has been used in immune cells) (Smith et al., 1990; Figures 5a1 and a2), resveratrol (Koo et al., 2006) and PD98059 (a MEK inhibitor) (Dudley et al., 1995; Figures 5b1 and b2). However, this was not the case for bromocriptine or 7-OH DPAT, which non-specifically inhibit mast cell degranulation (Seol et al., 2004) (data not shown).

Figure 5.

The functional relationship between the inhibitory activities on mast cell degranulation and the disinhibitory activities on the FcɛRI-mediated inhibition of M2PK. (a) Effects of quercetin (3–30 μM) and U-73122 (3–30 μM) on mast cell degranulation and FcɛRI-mediated inhibition of M2PK. (a1) RBL-2H3 cells were treated with increasing concentrations of quercetin or U-73122 for 20 min, and then stimulated with 1 μg mL−1 DNP-BSA for 10 min. Mast cell degranulation was measured as described under Materials and methods. ***P<0.001 compared with the vehicle-treated group (DMSO, no degranulation, not shown on the graph). (a2) After treating cells with quercetin or U-73122 as in panel (a1), cells were stimulated with 100 ng mL−1 DNP-BSA for 5 min. PK activity was measured as described under Materials and methods. ***P<0.001 compared with the vehicle/DNP-BSA-treated group. (b1 and b2) Effects of resveratrol and PD98059 on mast cell degranulation and FcɛRI-mediated inhibition of M2PK. The same experimental procedures as described in panel (a) were employed. *P<0.1, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001, compared with the corresponding control groups. BSA, bovine serum albumin; DMSO, dimethylsulphoxide; FcɛRI, high-affinity IgE receptor; M2PK, M2-type pyruvate kinase; PK, pyruvate kinase.

FcɛRI-mediated inhibition of M2-type PK results in accumulation of glycolytic intermediates, some of which might increase mast cell degranulation

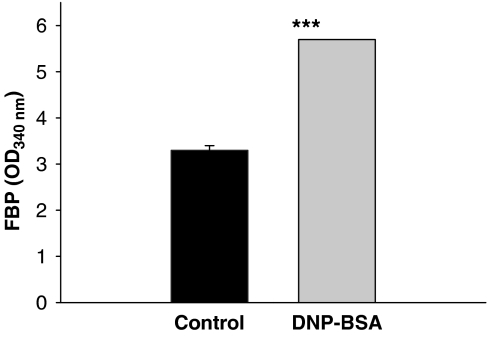

As PK-mediated conversion of PEP to pyruvate is the rate-limiting step in glycolytic processes, FcɛRI-mediated inhibition of M2PK would result in accumulation of glycolytic intermediates. Indeed, cellular level of fructose 1,6-bisphosphate, a glycolytic intermediate, increased in response to mast cell activation (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Relationship between FcɛRI activation and cellular content of fructose-1,6-bisphosphate. RBL-2H3 cells were stimulated with 100 ng mL−1 DNP-BSA for 4 h. ***P<0.001 compared with the control (PIPES buffer) group. BSA, bovine serum albumin; FcɛRI, high-affinity IgE receptor; RBL-2H3, rat basophilic leukaemia cells.

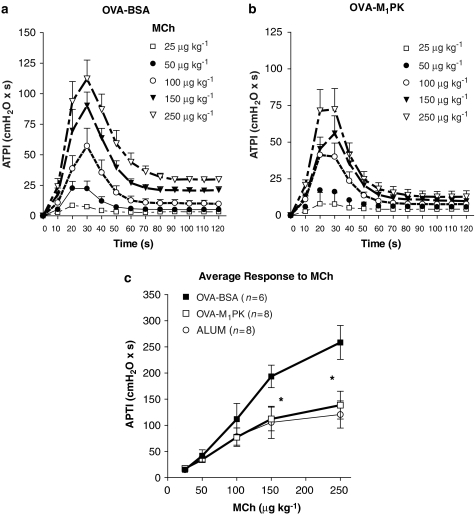

M1-type PK inhibits airway hyperresponsiveness in a mouse model of allergic airway inflammation

Next, we tested whether our in vitro results could be extended to in vivo studies. Since M1PK inhibited mast cell degranulation in vitro, we tested whether M1PK could inhibit in vivo allergic reactions. For this, we tested the effects of M1PK on a model of antigen-induced airways hyperresponsiveness in mice sensitized to ovalbumin (Walker et al, 1999). Treatment with exogenous M1PK (intraperitoneally) significantly reduced raised airway responsiveness to MCh, consequent on antigen challenge (Figures 7a–c).

Figure 7.

Effects of M1PK on airway responsiveness in mice sensitized and challenged with ovalbumin. (a and b) Effects of M1PK on peak airway pressure (airway pressure time index). Immediately before ovalbumin aerosol challenge, mice were intraperitoneally injected with either 20 U M1PK in 1% BSA/PBS (M1PK-treated group) or with 1% BSA/PBS (control group). Within 1–6 h after ovalbumin aerosol challenge, M1PK- and BSA-treated mice were tested for airway responsiveness to increasing concentrations of MCh. Mice tested 3–6 h after the end of ovalbumin aerosol challenge were given a ‘top-up' injection of M1PK (20 U) or 1% BSA/PBS. (c) Average response to methacholine between 20 and 50 s after injection of methacholine. Data shown are mean±s.e.mean. A multivariate analysis of variance for repeated measures was carried out. *P<0.05 BSA versus M1PK and alum treatment. BSA, bovine serum albumin; M1PK, M1-type pyruvate kinase; MCh, methacholine; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline.

Both M1PK- and sham-treated mice developed airway inflammation in response to ovalbumin treatment. This inflammation included eosinophils, which is characteristic of allergic airway disease. Although not statistically significant, there may be a trend for decreased eosinophilic inflammation in M1PK-treated mice (data not shown).

Discussion

The results depicted in Figures 1, 2 and 3 show that aggregation of FcɛRI induced mast cell degranulation and inhibition of cellular PK activity via tyrosine phosphorylation of M2PK. These effects were blocked by PP2, wortmannin and PKC inhibitors. This suggests that FcɛRI activation controls degranulation, PK activity and M2PK phosphorylation. These events are probably downstream of effects on Src, PI3K, PKC and calcium.

The γ-chain of FcɛRI is the main output pathway for signals initiated from crosslinking of IgE-occupied FcɛRIs. Upon activation of FcɛRI, Syk is recruited to the γ-chain and then activated by phosphorylation. In contrast, M2PK binds to the ITAM of the γ-chain at rest (Oak et al., 1999) and is inhibited by phosphorylation of the tyrosine residues. Furthermore, Src kinases do not appear to directly regulate M2PK as inhibition of PI-3K and PKC, which are located downstream of the Src kinases, abolished FcɛRI-mediated inhibition of M2PK. The tyrosine kinase responsible for M2PK phosphorylation remains unknown.

The extent of increase in of FcɛRI-mediated tyrosine phosphorylation of M2PK was much lower than Syk (Figure 3e) or phopsholipase-Cγ1 (Yoon et al., 2004), which were calcium-independent events. These results suggest that FcɛRI-mediated phosphorylation of M2PK might not be the only factor regulating the enzymatic activity of M2PK. Indeed, both basal activity and FcɛRI-mediated inhibition of M2PK were reduced in the absence of calcium (Figure 3d). Therefore, it is possible that M2PK is regulated via both Lyn-mediated increase in intracellular calcium level and Fyn-mediated PKC activation, as Lyn somehow controls the release of calcium by activating phopsholipase-Cγ. On the other hand, Fyn activates PKC through the Fyn-Gab2–PI-3K-signalling pathway and they collaboratively evoke mast cell degranulation (Nadler and Kinet, 2002).

It is known that at least six different PKC subtypes, conventional calcium-dependent PKC-α and PKC-β; novel calcium-independent PKC-δ, PKC-ɛ and PKC-θ; and atypical PKC-ξ (Ozawa et al., 1993), are present in RBL-2H3 cells. Gö6976 and Gö6983 are known to selectively inhibit PKC-α and PKC-β (Qatsha et al., 1993), and PKC-α, PKC-β, PKC-δ and PKC-ξ (Stempka et al., 1997), respectively. Both PKC inhibitors were equally effective in inhibiting mast cell degranulation and disinhibition of FcɛRI-induced regulation of M2PK, suggesting that PKC-α or PKC-β subtypes are likely involved in the modulation of M2PK.

Growth factors inhibiting M2PK through phosphorylation of the tyrosine residues have been proposed to promote cell growth through accumulation of glycolytic intermediates, which may then be used for synthesis of nucleotides and phospholipids (Eigenbrodt et al., 1992). Therefore, glycolytic intermediates that accumulate following FcɛRI-mediated inhibition of M2PK might also play an important role in mast cell degranulation.

Effects of application of exogenous M1PK in an animal model of allergic airways hyperresponsiveness were significant. It is generally accepted that allergic airway inflammation and airway hyperresponsiveness could be separated. We feel that M1PK is likely to exert its protective effect on airway bronchoconstriction through direct inhibition of mediator release from mast cells, as opposed to an effect resulting from decreased lung eosinophilic inflammation. It is notable that M1PK was only effective at the higher doses of MCh, suggesting that M1PK effectively limited maximal airway response. One of the symptoms of asthmatics is that their response to bronchoconstrictors does not plateau and excessive and uninhibited bronchoconstriction are observed in some asthmatics, leading to airflow obstruction and status asthmaticus. Therefore, M1PK could be a very useful agent in the treatment of acute bronchospastic attacks as well as in the maintenance of normal airflow.

One important question is what cellular processes, associated with degranulation, are initiated or inhibited by inactivation of M2PK? The tyrosine phosphorylation of M2PK alters the equilibrium of its structure from a tetramer to a dimer that has lower affinity for the substrate (Presek et al., 1988). Blocking glycolytic flux by inhibiting M2PK allows glycolytic intermediates that are proximal to pyruvate to accumulate and enhance cell proliferation (Eigenbrodt et al., 1977, 1992). These glycolytic intermediates are also used for biosynthesis of phospholipids or diacylglycerols that play important roles in mast cell degranulation (Bell and Coleman, 1980; Cohen and Brown, 2001). Hence, regulation of M2PK by the major signalling components of FcɛRI may act as a final common pathway for mast cell degranulation.

Interestingly, phenylketonuria (Koch et al., 2002) might provide a human disease model for testing this hypothesis concerning allergic response pathways. Phenylketonuria results from an inborn error in metabolism that results in accumulation of phenylalanine due to an inability to convert it to tyrosine. Phenylalanine inhibits the activity of M2PK (Feksa et al., 2002; Koch et al., 2002). Therefore, affected individuals would be predicted to show increased allergic responsiveness on this basis alone. Indeed, affected individuals have a higher incidence of eczema or asthma, which can be reversed by dietary manipulation to reduce phenylalanine intake.

In summary, FcɛRI-mediated decrease in M2PK activity is essential for initiating mast cell degranulation. Furthermore, manipulation of cellular glycolytic flux may provide a new strategy for preventing or treating allergies.

Acknowledgments

We appreciate Elias Y Kim and Meenoch Kim for manuscript proofreading. This work was supported by the Korea Research Foundation Grant funded by the Korean Government (MOEHRD, Basic Research Promotion Fund) (KRF-2006-312-C00616). JKLW is supported by the Veterans Administration Medical Center.

Abbreviations

- PK

pyruvate kinase

- PMA

phorbol myristate acetate

- RBL-2H3 cells

rat basophilic leukaemia cells

Conflict of interest

The authors state no conflict of interest.

References

- Bell RM, Coleman RA. Enzymes of glycerolipid synthesis in eukaryotes. Annu Rev Biochem. 1980;49:459–487. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.49.070180.002331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benhamou M, Ryba NJ, Kihara H, Nishikata H, Siraganian RP. Protein-tyrosine kinase p72syk in high affinity IgE receptor signaling. Identification as a component of pp72 and association with the receptor gamma chain after receptor aggregation. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:23318–23324. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blank U, Ra C, Miller L, White K, Metzger H, Kinet JP. Complete structure and expression in transfected cells of high affinity IgE receptor. Nature. 1989;337:187–189. doi: 10.1038/337187a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchtova L, Cech O. [Changes in certain enzymes of anaerobic glycolysis and pentose cycle in atopic eczema (author's transl)] Cesk Dermatol. 1982;57:23–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardenas JM. Pyruvate kinase from bovine muscle and liver. Methods Enzymol. 1982;90 Part E:140–149. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(82)90120-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrillo JJ, Ibares B, Esteban-Gamboa A, Feliu JE. Involvement of both phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and p44/p42 mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways in the short-term regulation of pyruvate kinase L by insulin. Endocrinology. 2001;142:1057–1064. doi: 10.1210/endo.142.3.7992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakravarty N. Inhibition of histamine release from rat mast cells by 2-deoxyglucose. Acta Pharmacol Toxicol (Copenhagen) 1967;25:35. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0773.1967.tb03025.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen JS, Brown HA. Phospholipases stimulate secretion in RBL mast cells. Biochemistry. 2001;40:6589–6597. doi: 10.1021/bi0103011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudley DT, Pang L, Decker SJ, Bridges AJ, Saltiel AR. A synthetic inhibitor of the mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:7686–7689. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.17.7686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eigenbrodt E, Mostafa MA, Schoner W. Inactivation of pyruvate kinase type M2 from chicken liver by phosphorylation, catalyzed by a cAMP-independent protein kinase. Hoppe Seylers Z Physiol Chem. 1977;358:1047–1055. doi: 10.1515/bchm2.1977.358.2.1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eigenbrodt E, Reinacher M, Scheefers-Borchel U, Scheefers H, Friis R. Double role for pyruvate kinase type M2 in the expansion of phosphometabolite pools found in tumor cells. Crit Rev Oncog. 1992;3:91–115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eiseman E, Bolen JB. Engagement of the high-affinity IgE receptor activates src protein-related tyrosine kinases. Nature. 1992;355:78–80. doi: 10.1038/355078a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feksa LR, Cornelio AR, Rech VC, Dutra-Filho CS, Wyse AT, Wajner M, et al. Alanine prevents the reduction of pyruvate kinase activity in brain cortex of rats subjected to chemically induced hyperphenylalaninemia. Neurochem Res. 2002;27:947–952. doi: 10.1023/a:1020351800882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guminska M, Sterkowicz J. Effect of sodium fluoride on glycolysis in human erythrocytes and Ehrlich ascites tumour cells in vitro. Acta Biochim Pol. 1976;23:285–291. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollenberg SM, Sternglanz R, Cheng PF, Weintraub H. Identification of a new family of tissue-specific basic helix–loop–helix proteins with a two-hybrid system. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:3813–3822. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.7.3813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imamura K, Tanaka T. Pyruvate kinase isozymes from rat. Methods Enzymol. 1982;90 Part E:150–165. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(82)90121-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch R, Burton B, Hoganson G, Peterson R, Rhead W, Rouse B, et al. Phenylketonuria in adulthood: a collaborative study. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2002;25:333–346. doi: 10.1023/a:1020158631102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koo N, Cho D, Kim Y, Choi HJ, Kim KM. Effects of resveratrol on mast cell degranulation and tyrosine phosphorylation of the signaling components of the IgE receptor. Planta Med. 2006;72:659–661. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-931568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levitt RC, Mitzner W. Expression of airway hyperreactivity to acetylcholine as a simple autosomal recessive trait in mice. FASEB J. 1988;2:2605–2608. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.2.10.3384240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Middleton E, Jr, Drzewiecki G, Krishnarao D. Quercetin: an inhibitor of antigen-induced human basophil histamine release. J Immunol. 1981;127:546–550. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miklaszewska M, Kobierzynska-Golab Z, Wasik F, Szybejko-Machaj G. [Activity of pyruvate kinase and glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase in polymorphonuclear granulocytes of patients with atopic dermatitis in the active stage and in remission] Przegl Dermatol. 1989;76:381–385. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadler MJ, Kinet JP. Uncovering new complexities in mast cell signaling. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:707–708. doi: 10.1038/ni0802-707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadler MJ, Matthews SA, Turner H, Kinet JP. Signal transduction by the high-affinity immunoglobulin E receptor FcɛRI: coupling form to function. Adv Immunol. 2000;76:325–355. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(01)76022-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noguchi T, Inoue H, Tanaka T. The M1- and M2-type isozymes of rat pyruvate kinase are produced from the same gene by alternative RNA splicing. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:13807–13812. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norn S, Elmgreen J, Stahl Skov P, Holme Jorgensen P, Ankjaergaard N, Hagen Petersen S. Influence of hyposensitization of ATP level and CO2 production of mast cells in anaphylaxis. Clin Exp Immunol. 1976;26:162–168. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oak MH, Cheong H, Kim KM. Activation of FcɛRI inhibits the pyruvate kinase through direct interaction with the γ-chain. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 1999;119:95–100. doi: 10.1159/000024183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okazaki T, Okazaki A, Reisman RE, Arbesman CE. Glycogenolysis and control of anaphylactic histamine release by cyclic adenosine monophosphate-related agents. II. Modification of histamine release by glycogenolytic metabolites. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1975;56:253–261. doi: 10.1016/0091-6749(75)90099-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozawa K, Yamada K, Kazanietz MG, Blumberg PM, Beaven MA. Different isozymes of protein kinase C mediate feedback inhibition of phospholipase C and stimulatory signals for exocytosis in rat RBL-2H3 cells. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:2280–2283. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parravicini V, Gadina M, Kovarova M, Odom S, Gonzalez-Espinosa C, Furumoto Y, et al. Fyn kinase initiates complementary signals required for IgE-dependent mast cell degranulation. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:741–748. doi: 10.1038/ni817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pemberton AD, Brown JK, Wright SH, Knight PA, Miller HR. The proteome of mouse mucosal mast cell homologues: the role of transforming growth factor beta1. Proteomics. 2006;6:623–631. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200500211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pleshkova SM, Tsvetkova TV. [Redox processes in allergic reactions of the delayed type to microbial antigens] Biull Eksp Biol Med. 1978;86:347–349. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Presek P, Reinacher M, Eigenbrodt E. Pyruvate kinase type M2 is phosphorylated at tyrosine residues in cells transformed by Rous sarcoma virus. FEBS Lett. 1988;242:194–198. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(88)81014-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qatsha KA, Rudolph C, Marme D, Schachtele C, May WS. Go 6976, a selective inhibitor of protein kinase C, is a potent antagonist of human immunodeficiency virus 1 induction from latent/low-level-producing reservoir cells in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:4674–4678. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.10.4674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reth M. Antigen receptor tail clue. Nature. 1989;338:383–384. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivera J. Molecular adapters in FcɛRI signaling and the allergic response. Curr Opin Immunol. 2002;14:688–693. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(02)00396-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salazar EP, Rozengurt E. Bombesin and platelet-derived growth factor induce association of endogenous focal adhesion kinase with Src in intact Swiss 3T3 cells. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:28371–28378. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.40.28371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz LB, Austen KF, Wasserman SI. Immunologic release of β-hexosaminidase and β-glucuronidase from purified rat serosal mast cells. J Immunol. 1979;123:1445–1450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senyshyn J, Baumgartner RA, Beaven MA. Quercetin sensitizes RBL-2H3 cells to polybasic mast cell secretagogues through increased expression of Gi GTP-binding proteins linked to a phospholipase C signaling pathway. J Immunol. 1998;160:5136–5144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seol IW, Kuo NY, Kim KM. Effects of dopaminergic drugs on the mast cell degranulation and nitric oxide generation in RAW 264.7 cells. Arch Pharm Res. 2004;27:94–98. doi: 10.1007/BF02980053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith RJ, Sam LM, Justen JM, Bundy GL, Bala GA, Bleasdale JE. Receptor-coupled signal transduction in human polymorphonuclear neutrophils: effects of a novel inhibitor of phospholipase C-dependent processes on cell responsiveness. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1990;253:688–697. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stempka L, Girod A, Muller HJ, Rincke G, Marks F, Gschwendt M, et al. Phosphorylation of protein kinase Cdelta (PKCδ) at threonine 505 is not a prerequisite for enzymatic activity. Expression of rat PKCδ and an alanine 505 mutant in bacteria in a functional form. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:6805–6811. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.10.6805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sulimenko V, Draberova E, Sulimenko T, Macurek L, Richterova V, Draber P, et al. Regulation of microtubule formation in activated mast cells by complexes of γ-tubulin with Fyn and Syk kinases. J Immunol. 2006;176:7243–7253. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.12.7243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takenaka M, Noguchi T, Inoue H, Yamada K, Matsuda T, Tanaka T. Rat pyruvate kinase M gene. Its complete structure and characterization of the 5′-flanking region. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:2363–2367. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker JK, Peppel K, Lefkowitz RJ, Caron MG, Fisher JT. Altered airway and cardiac responses in mice lacking G protein-coupled receptor kinase 3. Am J Physiol. 1999;276:R1214–R1221. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1999.276.4.R1214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yano H, Nakanishi S, Kimura K, Hanai N, Saitoh Y, Fukui Y, et al. Inhibition of histamine secretion by wortmannin through the blockade of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase in RBL-2H3 cells. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:25846–25856. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon E, Beom S, Cheong H, Kim S, Oak M, Cho D, et al. Differential regulation of phospholipase Cγ subtypes through FcɛRI, high affinity IgE receptor. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;325:117–123. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.09.216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]