Abstract

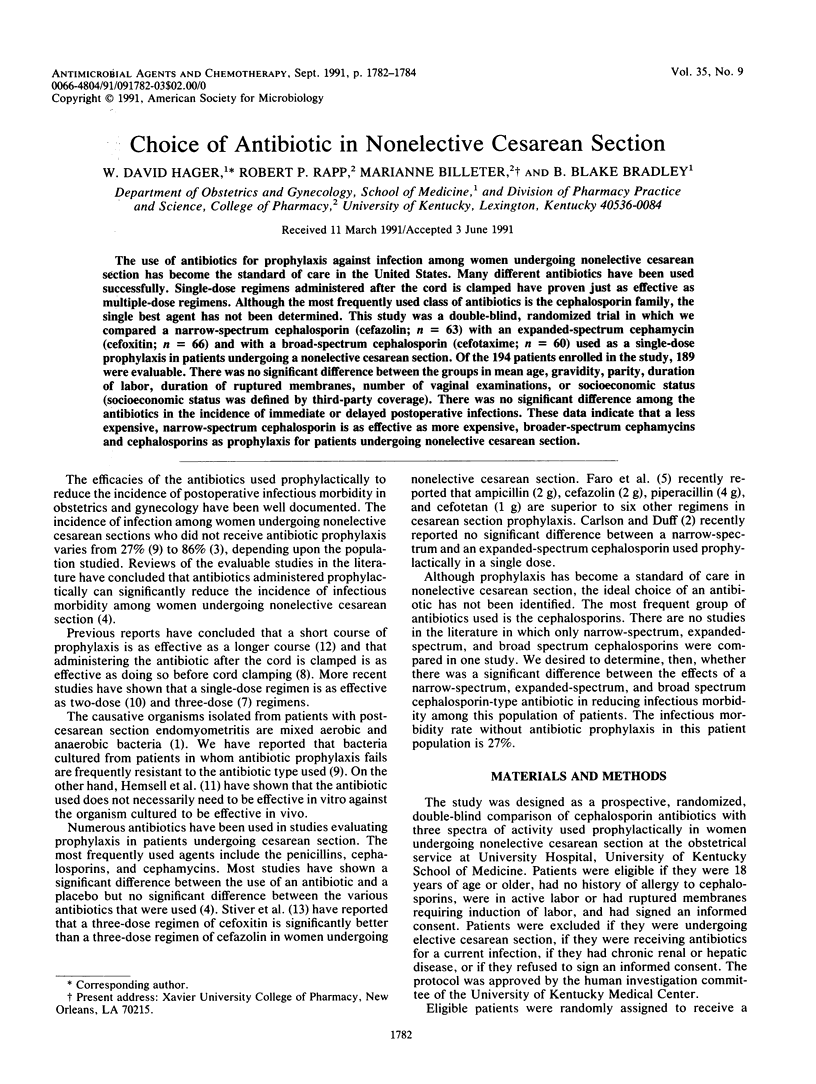

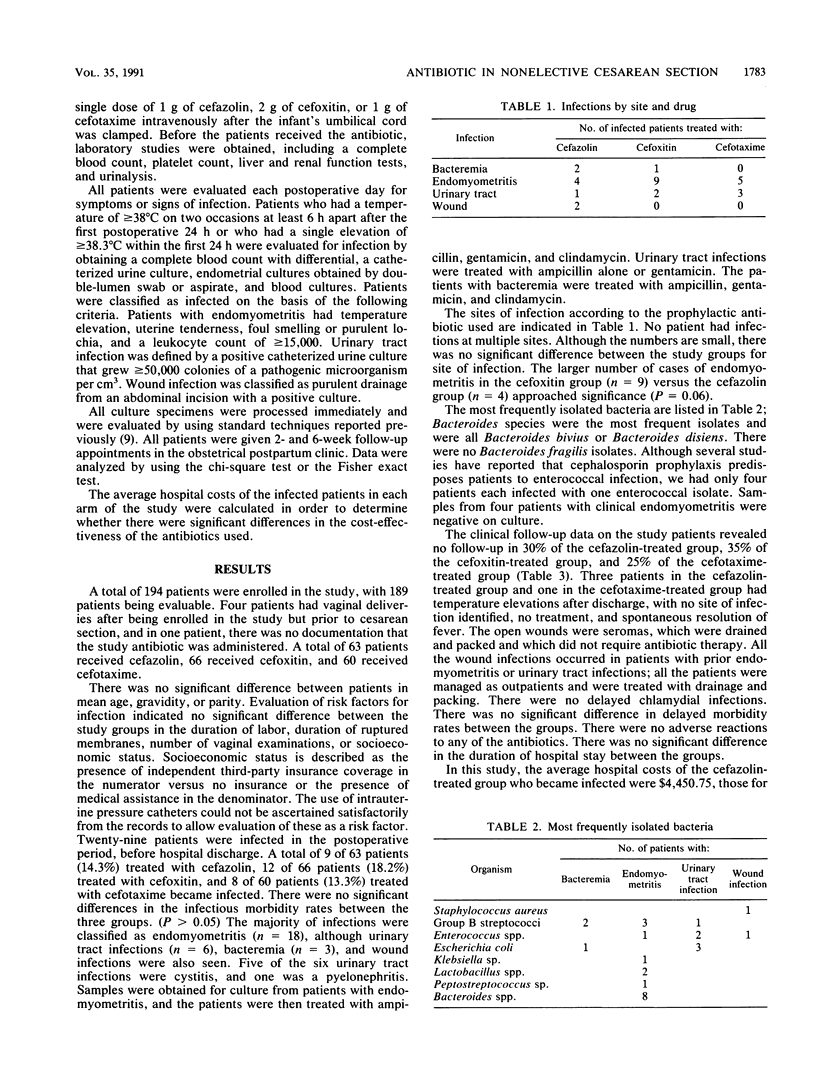

The use of antibiotics for prophylaxis against infection among women undergoing nonelective cesarean section has become the standard of care in the United States. Many different antibiotics have been used successfully. Single-dose regimens administered after the cord is clamped have proven just as effective as multiple-dose regimens. Although the most frequently used class of antibiotics is the cephalosporin family, the single best agent has not been determined. This study was a double-blind, randomized trial in which we compared a narrow-spectrum cephalosporin (cefazolin; n = 63) with an expanded-spectrum cephamycin (cefoxitin; n = 66) and with a broad-spectrum cephalosporin (cefotaxime; n = 60) used as a single-dose prophylaxis in patients undergoing a nonelective cesarean section. Of the 194 patients enrolled in the study, 189 were evaluable. There was no significant difference between the groups in mean age, gravidity, parity, duration of labor, duration of ruptured membranes, number of vaginal examinations, or socioeconomic status (socioeconomic status was defined by third-party coverage). There was no significant difference among the antibiotics in the incidence of immediate or delayed postoperative infections. These data indicate that a less expensive, narrow-spectrum cephalosporin is as effective as more expensive, broader-spectrum cephamycins and cephalosporins as prophylaxis for patients undergoing nonelective cesarean section.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Blanco J. D., Gibbs R. S., Castaneda Y. S., St Clair P. J. Correlation of quantitative amniotic fluid cultures with endometritis after cesarean section. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1982 Aug 15;143(8):897–901. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(82)90470-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson C., Duff P. Antibiotic prophylaxis for cesarean delivery: is an extended-spectrum agent necessary? Obstet Gynecol. 1990 Sep;76(3 Pt 1):343–346. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Palma R. T., Leveno K. J., Cunningham F. G., Pope T., Kappus S. S., Roark M. L., Nobles B. J. Identification and management of women at high risk for pelvic infection following cesarean section. Obstet Gynecol. 1980 May;55(5 Suppl):185S–192S. doi: 10.1097/00006250-198003001-00047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duff P. Prophylactic antibiotics for cesarean delivery: a simple cost-effective strategy for prevention of postoperative morbidity. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1987 Oct;157(4 Pt 1):794–798. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(87)80057-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faro S., Martens M. G., Hammill H. A., Riddle G., Tortolero G. Antibiotic prophylaxis: is there a difference? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1990 Apr;162(4):900–909. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(90)91290-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freiman J. A., Chalmers T. C., Smith H., Jr, Kuebler R. R. The importance of beta, the type II error and sample size in the design and interpretation of the randomized control trial. Survey of 71 "negative" trials. N Engl J Med. 1978 Sep 28;299(13):690–694. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197809282991304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonik B. Single- versus three-dose cefotaxime prophylaxis for cesarean section. Obstet Gynecol. 1985 Feb;65(2):189–193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon H. R., Phelps D., Blanchard K. Prophylactic cesarean section antibiotics: maternal and neonatal morbidity before or after cord clamping. Obstet Gynecol. 1979 Feb;53(2):151–156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hager W. D., Williamson M. M. Effects of antibiotic prophylaxis on women undergoing nonelective cesarean section in a community hospital. J Reprod Med. 1983 Oct;28(10):687–690. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawrylyshyn P. A., Bernstein P., Papsin F. R. Short-term antibiotic prophylaxis in high-risk patients following cesarean section. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1983 Feb 1;145(3):285–289. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(83)90712-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemsell D. L., Cunningham F. G., Nolan C. M., Miller T. T. Clinical experience with cefotaxime in obstetric and gynecologic infections. Rev Infect Dis. 1982 Sep-Oct;4 (Suppl):S432–S438. doi: 10.1093/clinids/4.supplement_2.s432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ledger W. J., Gee C., Lewis W. P. Guidelines for antibiotic prophylaxis in gynecology. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1975 Apr 15;121(8):1038–1045. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(16)33586-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stiver H. G., Forward K. R., Tyrrell D. L., Krip G., Livingstone R. A., Fugere P., Lemay M., Verschelden G., Hunter J. D., Carson G. D. Comparative cervical microflora shifts after cefoxitin or cefazolin prophylaxis against infection following cesarean section. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1984 Aug 1;149(7):718–721. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(84)90109-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]