Abstract

The protective effects of iodine on breast cancer have been postulated from epidemiologic evidence and described in animal models. The molecular mechanisms responsible have not been identified but laboratory evidence suggests that iodine may inhibit cancer promotion through modulation of the estrogen pathway. To elucidate the role of iodine in breast cancer, the effect of Lugol's iodine solution (5% I2, 10% KI) on gene expression was analyzed in the estrogen responsive MCF-7 breast cancer cell line. Microarray analysis identified 29 genes that were up-regulated and 14 genes that were down-regulated in response to iodine/iodide treatment. The altered genes included several involved in hormone metabolism as well as genes involved in the regulation of cell cycle progression, growth and differentiation. Quantitative RT-PCR confirmed the array data demonstrating that iodine/iodide treatment increased the mRNA levels of several genes involved in estrogen metabolism (CYP1A1, CYP1B1, and AKR1C1) while decreasing the levels of the estrogen responsive genes TFF1 and WISP2. This report presents the results of the first gene array profiling of the response of a breast cancer cell line to iodine treatment. In addition to elucidating our understanding of the effects of iodine/iodide on breast cancer, this work suggests that iodine/iodide may be useful as an adjuvant therapy in the pharmacologic manipulation of the estrogen pathway in women with breast cancer.

Keywords: Iodine, Gene Expression, Breast Cancer, Estrogen, Hormone Metabolism

Introduction

The high rate of breast disease in women with thyroid abnormalities (both dietary and clinical) suggests a correlation between thyroid and breast physiology 1-3. In addition, women with breast cancer have larger thyroid volumes then controls 2. Multiple studies suggest that abnormalities in iodine metabolism are the likely link 4-7. Additionally, the impact of iodine therapy for the maintenance of healthy breast tissue has been reported in both animal 4-7 and clinical studies 8, 9 yet the mechanisms responsible remain unclear.

Iodide (I-) uptake is observed in approximately 80% of breast cancers as well as fibrocystic breast disease and lactating breasts; however, quantitatively, no significant iodide uptake is reported in normal, non-lactating breast tissue 10. Clinical trials have demonstrated that women with cyclic mastalgia 9 or fibrocystic disease 8 can have symptomatic relief from treatment with molecular iodine (I2). Iodine deficiency, either dietary or pharmacologic, can lead to breast atypia and increased incidence of malignancy in animal models 11. Furthermore, iodine treatment can reverse dysplasia which results from iodine deficiency 5. Rat models using N-methyl-N-nitrosourea (NMU) and dimethyl-benz[a]anthracene (DMBA) to induce dysplasia and eventually carcinogenesis have shown that the presence of molecular iodine in the animal's diet can prevent tumor formation; yet, when iodine is removed from the diet, these animals develop tumors at rates comparable to those of control animals 5, 7. These data suggest that iodine diminishes early cancer progression through an inhibitory effect on cancer initiating cells.

Evidence indicates that the impact of iodine treatment on breast tissue is independent of thyroid function. For example, iodine deficient rats given the thyroid hormone thyroxine (T4) did not achieve reduced tumor growth following NMU treatment suggesting that the effect of iodine on tumor growth is independent of the thyroid gland or thyroid hormone 7. Additionally, Eskin et al and others have reported that administration of molecular iodine has a greater impact on tumor growth than the equivalent dose of iodide 5-9. Since the thyroid primarily utilizes iodide as opposed to iodine 5, this data supports the hypothesis that iodine is not acting through the thyroid.

In addition to differences in the metabolism of iodine, the mechanisms of iodine and iodide uptake appear to differ. While iodide uptake is essentially via the Sodium-Iodide Symporter (NIS) in the thyroid, data suggests that iodine uptake in the breast may be NIS-independent, possibly through a facilitated diffusion system 12. Together this data indicates that the effect of iodine on breast cancer progression is in part independent of thyroid function and suggests that iodine's protective effect on breast cancer progression is elicited through its direct interactions with breast cancer cells.

One proposed mechanism by which iodine may influence breast physiology and cancer progression is through an interaction with estrogen pathways. Qualitative changes in the estrogen receptor have been found in the breasts of iodine deficient rats compared to normal euthyroid animals suggesting that the iodine pathway may augment the synthesis of the estrogen receptor α (ERα) 13. Furthermore, when estrogen-responsive and estrogen-independent tumors were transplanted into mice, estrogen-responsive tumors had higher radioactive iodine uptakes than estrogen-independent transplants 14. Additionally, iodine deficiency induced atypia is worsened by estrogen addition 15. Together, this data supports the hypothesis that an interaction exists between iodine and estrogen within the breast 16. However, the precise molecular mechanisms responsible for this interaction remain unknown. We hypothesize that iodine effects breast physiology though an interaction with the estrogen pathway.

To test our hypothesis, we analyzed the effects of Lugol's iodine solution (5% I2, 10% KI) on global gene expression in the estrogen responsive MCF-7 breast cancer cell line. Analysis of the gene expression profile was used to evaluate potential mechanisms of action of iodine.

Results

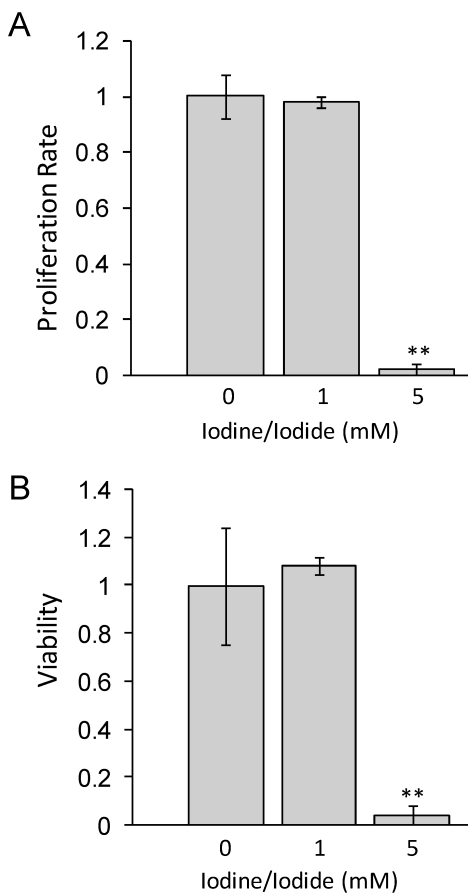

1mM iodide/iodine does not impact cellular proliferation or viability at 48 hours

Lugol's iodine solution, which contains 5.0% Iodine and 10% Iodide, was used to adjust standard RMPI 1640 medium to a concentration of either 1 mM or 5 mM Iodine/iodide. Medium was supplemented with all-trans-retinoic acid (tRA) and 17β-Estradiol (E2) for 24 hours prior to iodine treatment. Our data in figure 1 shows that at 48 hours, 1 mM iodine/iodide had no effect on cell proliferation or viability, relative to control cells. However, treatment with 5 mM iodine/iodide was toxic to the cells, inhibiting cell proliferation and reducing cell viability to less than 5% of control cells (P<0.01). Since no significant change in proliferation or viability was observed with 1 mM iodine/iodide, this concentration was used for the gene array studies.

Figure 1.

1 mM iodine/iodide does not impact cell viability or proliferation at 48 hours. MCF-7 cells were grown in RPMI-1640 supplemented with 1 µM tRA and 1 nM estradiol (control medium) or control medium supplemented with Lugol's iodine solution (5% iodine, 10% iodide) to a concentration of 1 mM iodine (1.0 mM iodine/iodide) or 5 mM iodine (5 mM iodine/iodide) for 48 hours and the effect on cell proliferation (A) and cell viability (B) was analyzed. Significant decrease in proliferation and viability was observed in the 5 mM iodine/iodide condition. Relative change in cell proliferation (A) and relative change in viability (B) for the control condition was set to one. Standard deviation is shown. ** denotes P ≤ 0.01

Interestingly, it has been reported that iodine alone can induce apoptosis at concentrations as low as 1µM 14, however we did not see cytotoxicity even at significantly higher (1mM) doses. Although the reasons for this difference remain unknown, several possible explanations exist. First, it may reflect differences in the cell lines used. Second, the presence of all-trans-retinoic acid, and/or 17β-estradiol may protect the MCF-7 cells from the cytotoxic effects of iodine previously reported. Finally, since previous studies have all used iodine alone while we used a combination of iodine and iodide, it is possible that the presence of iodide protects the MCF-7 cells from the detrimental effects of iodine. Indeed, it has been reported that iodide up to 5mM did not have a cytotoxic effect on MCF-7 cells 14. Furthermore, this may explain why breast cancers, which have increased NIS expression 17, 18 and increased iodide 18 uptake do not undergo apoptosis.

Gene Expression Profiling

Gene expression profiling was performed in triplicate on MCF-7 control cells and MCF-7 cells treated for 48 hours with medium supplemented with Lugol's Iodine solution to 1mM iodine/iodide. As described in the methods, all cells were pretreated for 24 hours with tRA and 17ß-estradiol prior to beginning iodine treatments. Data normalization and analysis are described in the Methods and Material section. Common genes with a mean change greater than two fold were considered significantly changed. Twenty-nine genes were up-regulated (Table 1A) and fourteen genes were down regulated-regulated (Table 1B).

Table 1.

MCF7 cells were treated with Lugol's iodine solution or vehicle alone for 48 hr (see Methods and Materials for details). RNA was isolated and subjected to Microarray Analysis (see Methods and Materials for details). 29 genes were upregulated ≥ 2.0-fold (A) and 14 genes were down regulated ≥ 2.0-fold (B) in response to treatment. Genes were than clustered into functional categories using the DAVID Bioinformatics Database Gene Functional Classification Tool (NIAID/NIH). The fold change in expression is relative to control cells. Bold genes were verified by qRT-PCR (Figure 2).

| A. 29 Genes that are Up-Regulated1 in Response to Iodine Treatment2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Cycle/Proliferation | Fold Change | ||

| NM_001673 | ASNS | asparagine synthetase | 4 |

| L24498 | GADD45A | growth arrest and DNA-damage-inducible, alpha3 | 2 |

| Steroid Metabolism | |||

| NM_000104 | CYP1B1 | cytochrome P450, family 1, subfamily B, polypeptide 13 | 11.3 |

| NM_001353 | AKR1C1 | aldo-keto reductase family 1, member C13 | 6 |

| NM_000499 | CYP1A1 | cytochrome P450, family 1, subfamily A, polypeptide 13 | 2.5 |

| Transcription | |||

| NM_003900 | SQSTM1 | sequestosome 1 | 2.8 |

| AB025432 | TSC22D3 | delta sleep inducing peptide, immunoreactor | 2.6 |

| DNA repair | |||

| NM_019058 | DDIT4 | DNA-damage-inducible transcript 4 | 2.2 |

| L24498 | GADD45A | growth arrest and DNA-damage-inducible, alpha3 | 2.0 |

| Lipid Metabolism | |||

| NM_000693 | ALDH1A3 | aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 family, member A3 | 3.2 |

| NM_004315 | ASAH1 | N-acylsphingosine amidohydrolase (acid ceramidase) 1 | 2.2 |

| tRNA synthesis | |||

| NM_004184 | WARS | tryptophanyl-tRNA synthetase | 3 |

| NM_002047 | GARS | glycyl-tRNA synthetase | 2.3 |

| NM_003680 | YARS | tyrosyl-tRNA synthetase | 2 |

| Other | |||

| NM_021158 | TRIB3 | tribbles homolog 3 (Drosophila) | 4 |

| NM_005218 | DEFB1 | defensin, beta 1 | 3.3 |

| NM_033197 | C20orf114 | chromosome 20 open reading frame 114 | 2.7 |

| NM_004753 | DHRS3 | dehydrogenase/reductase (SDR family) member 3 | 2.7 |

| NM_002083 | GPX2 | glutathione peroxidase 2 (gastrointestinal) 3 | 2.5 |

| NM_006636 | MTHFD2 | methylene tetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase | 2.5 |

| AF104032 | SLC7A5 | solute carrier family 7, member 5 | 2.4 |

| NM_004864 | GDF15 | growth differentiation factor 15 | 2.2 |

| NM_000416 | IFNGR1 | interferon gamma receptor 1 | 2.1 |

| NM_002356 | MARCKS | myristoylated alanine-rich protein kinase C substrate | 2.0 |

| Function Unknown | |||

| AK001064 | LOC86026 | hypothetical protein DKFZp434P055 | 3.5 |

| AK054816 | ORAOV1 | oral cancer overexpressed 1 | 3.0 |

| NM_006470 | TRIM16 | tripartite motif-containing 16 | 2.4 |

| AF245505 | MXRA5 | matrix-remodelling associated 5 | 2.3 |

| AL162069 | LOC144501 | hypothetical protein LOC144501 | 2.2 |

| BE884686 | LTB4DH | leukotriene B4 12-hydroxydehydrogenase | 2.1 |

| B. 14 Genes that are Down-Regulated4 in Response to Iodine Treatment2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Estrogen responsive genes | Fold Change | ||

| NM_003225 | TFF1 | trefoil factor 1 (estrogen-inducible sequence) 3 | -2.3 |

| NM_003881 | WISP2 | WNT1 inducible signaling pathway protein 23 | -2.4 |

| Cell Cycle genes | |||

| NM_003258 | TK1 | thymidine kinase 1, soluble | -3.7 |

| NM_002305 | LGALS1 | lectin, galactoside-binding, soluble, 1 (galectin 1) | -2.6 |

| NM_007019 | UBE2C | ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2C | -2.5 |

| NM_001071 | TYMS | thymidylate synthetase | -2.3 |

| NM_053056 | CCND1 | cyclin D1 (PRAD1: parathyroid adenomatosis 1) 3 | -2.0 |

| NM_002466 | MYBL2 | v-myb myeloblastosis viral oncogene homolog like 23 | -2.2 |

| Cell Growth/Proliferation Genes | |||

| NM_005264 | GFRA1 | GDNF family receptor alpha 13 | -2.5 |

| NM_007161 | LST1 | leukocyte specific transcript 1 | -2.5 |

| Ion Transport Genes | |||

| NM_004669 | CLIC3 | chloride intracellular channel 3 | -2.2 |

| Chromatin Organization | |||

| NM_002105 | H2AFX | H2A histone family, member X | -2.2 |

| Function Unknown | |||

| NM_007173 | PRSS23 | protease, serine, 23 | -3.7 |

| NM_006408 | AGR2 | anterior gradient 2 homolog (Xenopus laevis) | -2.1 |

1 Increase ≥ 2.0-fold relative to control

2 Accession number is to left, followed by gene symbol, name, and fold change.

3 Verified by QRT-PCR

4 Decrease ≥ 2.0-fold relative to control

Included in the down-regulated genes were genes involved in cell cycle (LGALS1, UBE2C, TYMS, MYBL2, and CCND1) 19-25, cell growth/differentiation (GFRA1) 26, nucleotide synthesis (TK1 and TYMS) 27, 28, and ubiquination and cyclin destruction (UBE2C) 19. Up-regulated genes include genes involved in estrogen metabolism (CYP1A1, CYP1B1, AKR1C1) 29, 30, DNA repair (GADD45A and DDIT4) 31, 32, cell cycle and proliferation (ASNS and GADD45A) 33, 34, tRNA synthesis (WARS, GARS, YARS) 35-37 and transcription (SQSTM1 and DSIPI) 38, 39.

The list was compared to a set of genes with experimentally or computationally determined estrogen responsive elements (EREs) in their promoter region 40. Nine (32%) of our up regulated genes (GADD45A, CYP1B1, TSC22D3, DDIT4, ASAH1, YARS, DHRS3, SLC7A5 and MARCKS) and five (38%) of our down regulated genes (TFF1, WISP2, TYMS, CCND1, and H2AFX) have putative EREs in their promoter region further supporting an interaction between iodine/iodide and the estrogen pathway.

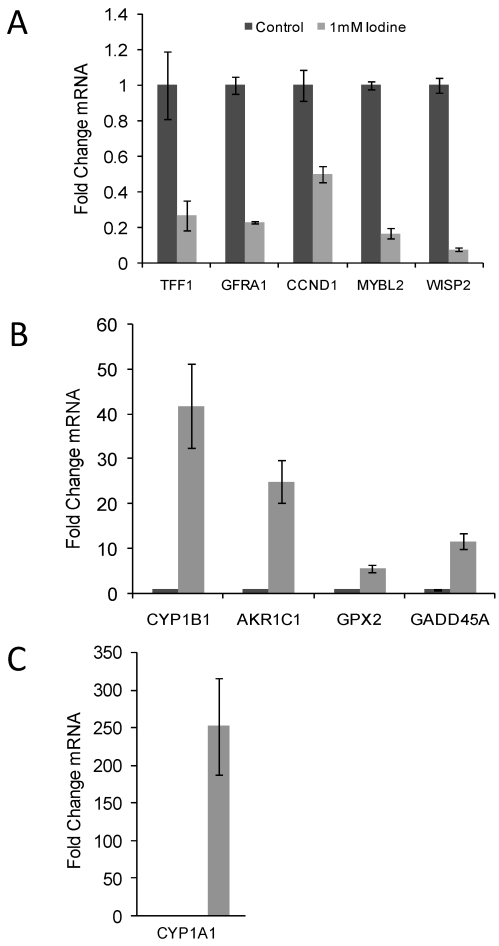

Quantitative RT-PCR confirmation of array data

10 genes of interest (5 up-regulated gene and 5 down-regulated genes) were chosen for quantitative RT-PCR confirmation. Up regulated genes included CYP1B1, AKR1C1, CYP1A1, GPX2, and GADD45A and the down regulated genes included GFRA1, TFF1, MYBL2, WISP2, and CCND1. Quantitative RT-PCR was run in triplicate and normalized to cyclophilin A. All ten genes demonstrated significant changes in steady state mRNA (p < 0.03) in response to 48 hr treatment with 1 mM iodine/iodide, confirming the accuracy of the array data (Figure 2). The two estrogen responsive genes (TFF1 and WISP2) showed a significant decrease in mRNA expression levels (Figure 2A) while the estrogen metabolism genes (CYP1A1, CYP1B1, and AKR1C1) demonstrated a significant increase in mRNA levels (Figures 2B and C).

Figure 2.

Quantitative RT-PCR confirmed the changes in gene expression identified by microarray analysis. RNA was isolated from control cell and cells grown in the presence of 1 mM iodine for 48 hours. QRT-PCR analysis of genes predicted by microarray analysis to be down-regulated (A) and up- regulated (B & C) in response to iodine treatment. Cyclophilin A was used as control for normalization. All 10 genes showed significant changes (P < 0.03) in response to iodine treatment in concordance with the array data. The mRNA level in the control samples was set to 1 and the fold change is shown. In panel C control bar is not visible. Dark bars represent control samples while grey bars represent samples treated with 1.0 mM Iodine. Standard Deviation bars are shown.

Discussion

As the body of evidence builds, the importance of iodine on the maintenance of healthy breast tissue and its role in carcinogenesis becomes clearer. Unveiling iodine's mechanism of action is of crucial importance. Verifying the protective effects of iodine in breast cancer pathways will improve our understanding of breast cancer physiology and potentially lead researchers toward the development of novel treatments or enhancements of current therapies. In this study we provide the first gene array profiling of an estrogen responsive breast cancer cell line demonstrating that the combination of iodine and iodide alters gene expression. Among the list of altered genes were several genes documented to be estrogen responsive such as TFF1 and WISP2. Furthermore, the list contained several genes involved in the estrogen response including Phase I estrogen metabolizing enzymes (CYP1A1 and CYP1B) and Cyclin D1, a competitive inhibitor of BRCA1 41.

Consistent with our initial hypothesis that iodine/iodide interacts with the estrogen pathway, we found that iodine/iodide altered mRNA expression of several genes involved in the estrogen pathway and down-regulated several estrogen responsive genes. Furthermore, many of the genes identified contain putative Estrogen Responsive Elements in their promoter region. One potential mechanism in which iodine/iodide can repress the estrogen effect on cellular metabolism is through alterations in the Cytochrome P450 pathway. Our data shows that treatment with iodine and iodide increases the mRNA levels of Cytochrome P450 1A1 (CYP1A1) and 1B1 (CYP1B1), two estrogen phase I estrogen metabolizing enzymes that oxidizes 17β-estradiol to 2-hydoxyestradiol (2-OH-E2) and 4-hydoxyestradiol (4-OH-E2), respectively. These catechol estrogens can be further oxidized to quinones. 3,4-estradiol quinine, a metabolite of 4-OH-E2, has been shown to react with DNA forming de-purinating adducts resulting in genotoxicity 42, while data suggests that 2-OH-E2 can be metabolized to 2-methoxyestradiol, an estrogen metabolite with anti-proliferative effects 43. The observed increase in the CYP1A1/CYP1B1 ratio may shift the direction of estrogen metabolism favoring 2-OH-E2 which may either directly affect proliferation through increasing 2-methoxyestradiol, decreasing 3, 4-estradiol quinone or indirectly via the inactivation of E2. The importance of the CYP1A1/CYP1B1 ratio in-vivo is evident in the increased presence of 4-OH-E2 in breast cancer tissue compared to non breast cancer controls 44. However, the regulation and interplay between CYP1A1, CYP1B1, other Phase I and II enzymes and estrogen is complex, being influenced by multiple factors and multiple polymorphisms, thus more data is required to illuminate the importance of these changes in response to iodine.

In addition to affecting estrogen metabolism, iodine/iodide may also inhibit estrogen induced transcription via increased BRCA1 activity. BRCA1 is a known inhibitor of ERα transcription while Cyclin D1 is thought to enhance the estrogen response via a competitive inhibition with BRCA1 41. Our data demonstrates decreased Cyclin D1 mRNA which could result in decreased competitive inhibition of BRCA1 allowing BRCA1 to inhibit estrogen induced transcription. Increased transcription of GADD45A, CYP1B1, and CYP1A1 are consistent with increased BRCA1 activity 34, 45.

Either through its interactions with estrogen or through estrogen independent mechanisms, the combination of iodine and iodide seems to have an impact on genes involved with cell growth (GFRA1 and GDF15), cell cycle (LGALS1, UBE2C, MYBL2, TYMS, CCND1, ASNS, GADD45A), and differentiation (GFRA1, GDF15) . Of particular interest is the down-regulation of GFRA1. GFRA1 has been shown to increase NUMB expression which in turn degrades NOTCH; the net result of decreased GFRA1 expression is increased NOTCH. NOTCH has been implicated in stem cell differentiation during breast development, preventing uncontrolled basal cell proliferation during alveolar development 46. As such, iodine may play a crucial role during periods of breast maturation during puberty and pregnancy.

Finally, this data further supports the need for clinical studies involving the use of iodine/iodide in conjunction with current estrogen modulation therapies. Despite the efficacy of current treatments of breast cancer with medications such as Tamoxifen, the development of resistant cancers remains critically important. It has been found that CCND1 over-expression plays an important role in the development of Tamoxifen resistant breast cancer 25, 47-49; our data shows that iodine/iodide treatment can decrease mRNA levels of CCND1. This provides two potential mechanisms by which iodine/iodide could enhance the efficacy of Tamoxifen therapy: 1) having an additive effect on estrogen inhibition and 2) inhibiting the expression of CCND1 thus preventing or slowing the development of Tamoxifen resistance.

The results presented in this paper build on the substantial epidemiologic, clinical and cellular data regarding the actions of iodine in breast physiology. We suggest that the protective effects of iodine/iodide on breast disease may be in part through the inhibition or modulation of estrogen pathways. Data presented suggests that iodine/iodide may inhibit the estrogen response through 1) up-regulating proteins involved in estrogen metabolism (specifically through increasing the CYP1A1/1B1 ratio), and 2) decreasing BRCA1 inhibition thus permitting its inhibition of estrogen responsive transcription. These data open the way for further defining pathways impacted by the essential element, iodine, in the cellular physiology of extrathyroidal tissues, particularly the breast.

Materials and Methods

Cell lines

Human MCF-7 breast cancer cells (ATTC, Manassas, VA) were grown in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, penicillin, and streptomycin (Gemini Bio-Products, West Sacramento, CA) and incubated at 37˚C with 5% CO2.

Iodine and estrogen treatments

24 hours prior to iodine treatment cells were grown in control medium consisting of RPMI 1640 supplemented with 1 µM all-trans-retinoic acid (tRA) in DMSO vehicle and 1 nM 17ß-estradiol (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) in EtOH vehicle. DMSO and EtOH concentrations did not exceed 0.1% (v/v). Lugol's iodine solution (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) containing 5% I2 and 10% KI was added to the experimental medium to a concentration of 1mM iodine/iodide. Cells were grown for an additional 48 hours.

Proliferation and Viability Assays

To evaluate the effects of iodine on proliferation, MCF-7 cells were plated on 96 well plates. Cells were pretreated with tRA and estradiol control medium and treated with iodine as described above. MTT proliferation assay (ATTC, Manassas, VA) was performed in accordance with the manufacturer. To test cell viability, cells were grown on a six well plates, trypsinized, stained using ViaCount® Reagents (Guava Technologies, Hayward, CA) and analyzed using flow cytometry (Guava EasyCyte Mini.)

RNA isolation

Following iodine treatment, total RNA was isolated using RNAeasy mini kits (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) according to the manufacturer. RNA was quantified using a Bio-Mini DNA/RNA/Protein Analyzer (Shimadzu Scientific Instruments, Inc.).

Microarray Analysis

Microarray slides were provided by the Genomic Facility at Drexel University College of Medicine containing 23,000 human 70mer oligos (Human Genome Oligo Set Version 2.0) on a glass slide. RNA amplification and labeling was performed using the MessageAmp™ aRNA Amplification Kit (Ambion, Austin, TX). Equal micrograms of fragmented, labeled aRNA was hybridized to a cDNA microarray using SlydeHybe Buffer #1 (Ambion, Austin, TX). After 24 hours of hybridization microarray slides were washed and scanned on Axon 4000B Dual Laser Slide Scanner (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA.). Data was analyzed using GenePix (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA.) disregarding signals with a signal to noise ratio < 1 and a sum of the means <600. Three biological duplicates were then analyzed using the GenePix AutoProcessor (GPAP) program. Pre-processing and normalization of data was accomplished using R-project statistical environment (http://www.r-project.org) and Bioconductor (http://www.bioconductor.org) through the GPAP website (http://darwin.biochem.okstate.edu/gpap). The resulting data was annotated and analyzed using the DAVID Bioinformatics Database Gene Functional Classification Tool (NIAID/NIH). Genes with a greater than 2 fold change in 2 or more arrays were considered significant.

Quantitative RT-PCR

Primer probe sets were purchased from Applied Biosystems (Foster City, CA). Probes and Assay ID included Cytchrome P450 1A1 (CYP1A1; Hs00153120_m1), Cytochrome P450 1B1 (CYP1B1; Hs00164383_m1), Aldo-keto Reductase 1C1 (AKR1C1; Hs00413886_m1), Glutathione Peroxidase 2 (GPX2; Hs00702173_s1), Growth Arrest and DNA-Damage-Inducible α (GADD45A; Hs00169255_m1), trefoil factor 1 (TFF1; Hs00170216_m1), GDNF family receptor alpha 1 (GFRA1; Hs00237133_m1), Cyclin D1 (CCND1; Hs00277039_m1), v-myb myeloblastosis viral oncogene homolog (avian)-like 2 (MYBL2; Hs00231158_m1), and WNT1 inducible signaling pathway protein 2 (WISP2; Hs00180242_m1). Quantitative RT-PCR was performed using Brilliant QRT-PCR Master Mix kits (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) and analyzed using the Mx3000P real-time PCR machine (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). Cyclophilin A was used for normalization.

References

- 1.Kalache A, Vessey MP, McPherson K. Thyroid disease and breast cancer: findings in a large case-control study. Br J Surg. 1982;69:434–435. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800690731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smyth PP, Smith DF, McDermott EW, Murray MJ, Geraghty JG, O'Higgins NJ. A direct relationship between thyroid enlargement and breast cancer. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1996;81:937–941. doi: 10.1210/jcem.81.3.8772554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vassilopoulou-Sellin R, Palmer L, Taylor S, Cooksley CS. Incidence of breast carcinoma in women with thyroid carcinoma. Cancer. 1999;85:696–705. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19990201)85:3<696::aid-cncr20>3.0.co;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eskin BA. Dietary iodine and cancer risk. Lancet. 1976;2:807–808. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(76)90646-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eskin BA, Grotkowski CE, Connolly CP, Ghent WR. Different tissue responses for iodine and iodide in rat thyroid and mammary glands. Biol Trace Elem Res. 1995;49:9–19. doi: 10.1007/BF02788999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Funahashi H, Imai T, Tanaka Y, Tobinaga J, Wada M, Morita T, Yamada F, Tsukamura K, Oiwa M, Kikumori T et al. Suppressive effect of iodine on DMBA-induced breast tumor growth in the rat. J Surg Oncol. 1996;61:209–213. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9098(199603)61:3<209::AID-JSO9>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Garcia-Solis P, Alfaro Y, Anguiano B, Delgado G, Guzman RC, Nandi S, Diaz-Munoz M, Vazquez-Martinez O, Aceves C. Inhibition of N-methyl-N-nitrosourea-induced mammary carcinogenesis by molecular iodine (I2) but not by iodide (I-) treatment Evidence that I2 prevents cancer promotion. MolCell Endocrinol. 2005;236:49–57. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2005.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ghent WR, Eskin BA, Low DA, Hill LP. Iodine replacement in fibrocystic disease of the breast. Can J Surg. 1993;36:453–460. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kessler JH. The effect of supraphysiologic levels of iodine on patients with cyclic mastalgia. Breast J. 2004;10:328–336. doi: 10.1111/j.1075-122X.2004.21341.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tazebay UH, Wapnir IL, Levy O, Dohan O, Zuckier LS, Zhao QH, Deng HF, Amenta PS, Fineberg S, Pestell RG, Carrasco N. The mammary gland iodide transporter is expressed during lactation and in breast cancer. NatMed. 2000;6:871–878. doi: 10.1038/78630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Strum JM. Effect of iodide-deficiency on rat mammary gland. Virchows ArchB Cell PatholInclMolPathol. 1979;30:209–220. doi: 10.1007/BF02889103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arroyo-Helguera O, Anguiano B, Delgado G, Aceves C. Uptake and antiproliferative effect of molecular iodine in the MCF-7 breast cancer cell line. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2006;13:1147–1158. doi: 10.1677/erc.1.01250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eskin BA, Jacobson HI, Bolmarich V, Murray JA. Breast atypia in altered iodine states: Intracellular changes. Senologia. 1977;2:61–65. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thorpe SM. Increased uptake of iodide by hormone-responsive compared to hormone-independent mammary tumors in GR mice. Int J Cancer. 2006:345–350. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910180312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eskin BA, Bartuska DG, Dunn MR, Jacob G, Dratman MB. Mammary gland dysplasia in iodine deficiency. Studies in rats. Jama. 1967;200:691–695. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eskin BA, Shuman R, Krouse T, Merion JA. Rat mammary gland atypia produced by iodine blockade with perchlorate. Cancer Res. 1975;35:2332–2339. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tazebay UH, Wapnir IL, Levy O, Dohan O, Zuckier LS, Zhao QH, Deng HF, Amenta PS, Fineberg S, Pestell RG, Carrasco N. The mammary gland iodide transporter is expressed during lactation and in breast cancer. Nat Med. 2000;6:871–878. doi: 10.1038/78630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Upadhyay G, Singh R, Agarwal G, Mishra SK, Pal L, Pradhan PK, Das BK, Godbole MM. Functional expression of sodium iodide symporter (NIS) in human breast cancer tissue. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2003;77:157–165. doi: 10.1023/a:1021321409159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Townsley FM, Aristarkhov A, Beck S, Hershko A, Ruderman JV. Dominant-negative cyclin-selective ubiquitin carrier protein E2-C/UbcH10 blocks cells in metaphase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:2362–2367. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.6.2362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fischer C, Sanchez-Ruderisch H, Welzel M, Wiedenmann B, Sakai T, Andre S, Gabius HJ, Khachigian L, Detjen KM, Rosewicz S. Galectin-1 interacts with the {alpha}5{beta}1 fibronectin receptor to restrict carcinoma cell growth via induction of p21 and p27. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:37266–37277. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411580200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kaneda S, Nalbantoglu J, Takeishi K, Shimizu K, Gotoh O, Seno T, Ayusawa D. Structural and functional analysis of the human thymidylate synthase gene. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:20277–20284. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bessa M, Joaquin M, Tavner F, Saville MK, Watson RJ. Regulation of the cell cycle by B-Myb. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2001;27:416–421. doi: 10.1006/bcmd.2001.0399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Muller-Tidow C, Wang W, Idos GE, Diederichs S, Yang R, Readhead C, Berdel WE, Serve H, Saville M, Watson R, Koeffler HP. Cyclin A1 directly interacts with B-myb and cyclin A1/cdk2 phosphorylate B-myb at functionally important serine and threonine residues: tissue-specific regulation of B-myb function. Blood. 2001;97:2091–2097. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.7.2091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Doisneau-Sixou SF, Sergio CM, Carroll JS, Hui R, Musgrove EA, Sutherland RL. Estrogen and antiestrogen regulation of cell cycle progression in breast cancer cells. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2003;10:179–186. doi: 10.1677/erc.0.0100179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kilker RL, Planas-Silva MD. Cyclin D1 is necessary for tamoxifen-induced cell cycle progression in human breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2006;66:11478–11484. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wiesenhofer B, Weis C, Humpel C. Glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) is a proliferation factor for rat C6 glioma cells: evidence from antisense experiments. Antisense Nucleic Acid Drug Dev. 2000;10:311–321. doi: 10.1089/oli.1.2000.10.311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fujiwaki R, Hata K, Nakayama K, Moriyama M, Iwanari O, Katabuchi H, Okamura H, Sakai E, Miyazaki K. Thymidine kinase in epithelial ovarian cancer: relationship with the other pyrimidine pathway enzymes. Int J Cancer. 2002;99:328–335. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tsourouflis G, Theocharis SE, Sampani A, Giagini A, Kostakis A, Kouraklis G. Prognostic and Predictive Value of Thymidylate Synthase Expression in Colon Cancer. Dig Dis Sci. 2008;53(5):1289–96. doi: 10.1007/s10620-007-0008-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tsuchiya Y, Nakajima M, Yokoi T. Cytochrome P450-mediated metabolism of estrogens and its regulation in human. Cancer Lett. 2005;227:115–124. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2004.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rizner TL, Smuc T, Rupreht R, Sinkovec J, Penning TM. AKR1C1 and AKR1C3 may determine progesterone and estrogen ratios in endometrial cancer. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2006;248:126–135. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2005.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maeda T, Hanna AN, Sim AB, Chua PP, Chong MT, Tron VA. GADD45 regulates G2/M arrest, DNA repair, and cell death in keratinocytes following ultraviolet exposure. J Invest Dermatol. 2002;119:22–26. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2002.01781.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ellisen LW, Ramsayer KD, Johannessen CM, Yang A, Beppu H, Minda K, Oliner JD, McKeon F, Haber DA. REDD1, a developmentally regulated transcriptional target of p63 and p53, links p63 to regulation of reactive oxygen species. Mol Cell. 2002;10:995–1005. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00706-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Greco A, Gong SS, Ittmann M, Basilico C. Organization and expression of the cell cycle gene, ts11, that encodes asparagine synthetase. Mol Cell Biol. 1989;9:2350–2359. doi: 10.1128/mcb.9.6.2350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhan Q. Gadd45a, a p53- and BRCA1-regulated stress protein, in cellular response to DNA damage. Mutat Res. 2005;569:133–143. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2004.06.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jia J, Li B, Jin Y, Wang D. Expression, purification, and characterization of human tyrosyl-tRNA synthetase. Protein Expr Purif. 2003;27:104–108. doi: 10.1016/s1046-5928(02)00576-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bange FC, Flohr T, Buwitt U, Bottger EC. An interferon-induced protein with release factor activity is a tryptophanyl-tRNA synthetase. FEBS Lett. 1992;300:162–166. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(92)80187-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Antonellis A, Lee-Lin SQ, Wasterlain A, Leo P, Quezado M, Goldfarb LG, Myung K, Burgess S, Fischbeck KH, Green ED. Functional analyses of glycyl-tRNA synthetase mutations suggest a key role for tRNA-charging enzymes in peripheral axons. J Neurosci. 2006;26:10397–10406. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1671-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ciani B, Layfield R, Cavey JR, Sheppard PW, Searle MS. Structure of the ubiquitin-associated domain of p62 (SQSTM1) and implications for mutations that cause Paget's disease of bone. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:37409–37412. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307416200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vogel P, Magert HJ, Cieslak A, Adermann K, Forssmann WG. hDIP--a potential transcriptional regulator related to murine TSC-22 and Drosophila shortsighted (shs)--is expressed in a large number of human tissues. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1996;1309:200–204. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4781(96)00177-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jin VX, Sun H, Pohar TT, Liyanarachchi S, Palaniswamy SK, Huang TH, Davuluri RV. ERTargetDB: an integral information resource of transcription regulation of estrogen receptor target genes. J Mol Endocrinol. 2005;35:225–230. doi: 10.1677/jme.1.01839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang C, Fan S, Li Z, Fu M, Rao M, Ma Y, Lisanti MP, Albanese C, Katzenellenbogen BS, Kushner PJ et al. Cyclin D1 antagonizes BRCA1 repression of estrogen receptor alpha activity. Cancer Res. 2005;65:6557–6567. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zahid M, Kohli E, Saeed M, Rogan E, Cavalieri E. The greater reactivity of estradiol-3,4-quinone vs estradiol-2,3-quinone with DNA in the formation of depurinating adducts: implications for tumor-initiating activity. Chem Res Toxicol. 2006;19:164–172. doi: 10.1021/tx050229y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.LaVallee TM, Zhan XH, Herbstritt CJ, Kough EC, Green SJ, Pribluda VS. 2-Methoxyestradiol inhibits proliferation and induces apoptosis independently of estrogen receptors alpha and beta. Cancer Res. 2002;62:3691–3697. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rogan EG, Badawi AF, Devanesan PD, Meza JL, Edney JA, West WW, Higginbotham SM, Cavalieri EL. Relative imbalances in estrogen metabolism and conjugation in breast tissue of women with carcinoma: potential biomarkers of susceptibility to cancer. Carcinogenesis. 2003;24:697–702. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgg004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kang HJ, Kim HJ, Kim SK, Barouki R, Cho CH, Khanna KK, Rosen EM, Bae I. BRCA1 modulates xenobiotic stress-inducible gene expression by interacting with ARNT in human breast cancer cells. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:14654–14662. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601613200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Callahan R, Egan SE. Notch signaling in mammary development and oncogenesis. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. 2004;9:145–163. doi: 10.1023/B:JOMG.0000037159.63644.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bostner J, Ahnstrom Waltersson M, Fornander T, Skoog L, Nordenskjold B, Stal O. Amplification of CCND1 and PAK1 as predictors of recurrence and tamoxifen resistance in postmenopausal breast cancer. Oncogene. 2007;26:6997–7005. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jirstrom K, Stendahl M, Ryden L, Kronblad A, Bendahl PO, Stal O, Landberg G. Adverse effect of adjuvant tamoxifen in premenopausal breast cancer with cyclin D1 gene amplification. Cancer Res. 2005;65:8009–8016. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stendahl M, Kronblad A, Ryden L, Emdin S, Bengtsson NO, Landberg G. Cyclin D1 overexpression is a negative predictive factor for tamoxifen response in postmenopausal breast cancer patients. Br J Cancer. 2004;90:1942–1948. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]