Abstract

In advanced pancreatic cancer, level one evidence has established a significant survival advantage with chemotherapy, compared to best supportive care. The treatment-associated toxicity needs to be evaluated. This study examines the secondary outcome measures for chemotherapy in advanced pancreatic cancer using meta-analyses. A systematic review was undertaken employing Cochrane methodology, with search of databases, conference proceedings and trial registers. The secondary end points were progression-free survival (PFS)/time to progression (TTP) (summarised using the hazard ratio (HR)), response rate and toxicity (summarised using relative risk). There was no significant advantage of 5FU combinations vs 5FU alone for TTP (HR=1.02; 95% CI=0.85–1.23) and toxicity. Progression-free survival (HR 0.78; CI 0.70–0.88), TTP (HR=0.85; 95% CI=0.72–0.99) and overall response rate (RR=0.56; 95% CI=0.46–0.68) were significantly better for gemcitabine combination chemotherapy, but offset by the greater grade 3/4 toxicity thrombocytopenia (RR=1.94; 95% CI=1.32–2.84), leucopenia (RR=1.46; 95% CI=1.15–1.86), neutropenia (RR=1.48; 95% CI=1.07–2.05), nausea (RR=1.77; 95% CI=1.37–2.29), vomiting (RR=1.64; 95% CI=1.24–2.16) and diarrhoea (RR=2.73; 95% CI=1.87–3.98). There is no significant advantage on secondary end point analyses for administering 5FU in combination over 5FU alone. There is improved PFS/TTP and response rate, with gemcitabine-based combinations, although this comes with greater toxicity.

Keywords: meta-analyses, pancreatic cancer, chemotherapy

Advanced pancreatic cancer has a poor prognosis, with a median survival of 2–6 months for metastatic disease and 6–11 months for locally advanced disease (Cancer Research, 2006). Chemotherapy with fluoropyrimidines, gemcitabine, either alone or in combination with other agents (Rocha Lima and Flores, 2006), and chemoradiation are all used in the palliative setting (Mancuso et al, 2006). Overall survival meta-analyses, using relative risk (Yip et al, 2006) or the hazard ratio (HR) (Fung et al, 2003; Sultana et al, 2007), have established a role for chemotherapy over best supportive care. Questions have arisen as to the cost at which this survival advantage is gained, in particular, the toxicity profile. Following from our previous survival meta-analysis (Sultana et al, 2007), we present the results of the secondary outcome measures meta-analysis.

There has only been one fully published meta-analysis evaluating secondary outcome measures, with no pooling of the results of these end points (Yip et al, 2006). Other published reports have assessed this only for the comparison of gemcitabine combinations vs gemcitabine. (Liang, 2005; Milella et al, 2006; Heinemann et al, 2006a; Xie et al, 2006a, 2006b; Bria et al, 2007; Heinemann et al, 2007). To fully evaluate the risks vs the benefits of treatment, a comprehensive evaluation including assessment of several composite end points is required.

Methods

Detailed description of the methodology of the systematic review has already been described (Sultana et al, 2007).

The secondary outcome measures evaluated were progression-free survival (PFS – time from randomisation to progression or death) or time to progression (TTP – time from randomisation to disease progression), overall response rate (ORR – number of partial and complete responses) and toxicity (as published by the trialists, was recorded, with the most frequently reported events analysed).

Individual trial level time to event data (PFS/TTP) were summarised by the log HR and its variance was approximated using previously reported methods (Parmar et al, 1998; Williamson et al, 2002). Trial level log HRs and their variances were pooled using an inverse variance, weighted average and results presented as a HR and 95% confidence interval.

Dichotomous data (ORR and toxicity) were summarised using relative risks and 95% confidence intervals and pooled using the Mantel–Haenszel method for combining trials (Deeks et al, 2001). Heterogeneity was assessed by visual inspection of the Forrest plot, the Cochran's χ2 test (using a 10% significance level, in view of the low power of tests for heterogeneity (Paul and Donner, 1992)) and interpretation of the I2 statistic (percentage of variation due to heterogeneity with higher values indicating a greater degree of heterogeneity) (Deeks et al, 2004). A fixed effect approach was adopted unless there was evidence of significant unexplained heterogeneity in which case a random effects approach was used.

Results

Results are presented for the comparisons with adequate data to assess the secondary outcome measures.

5FU vs 5FU combination chemotherapy

There were five studies (Supplementary Table 1) (Kovach et al, 1974; Cullinan et al, 1985, 1990; Ducreux et al, 2002; Maisey et al, 2002) (n=700) included in this comparison. A HR of <1 indicates a survival advantage for 5FU combination chemotherapy.

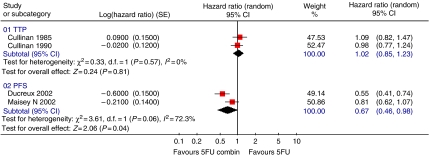

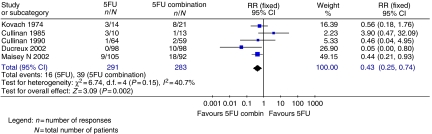

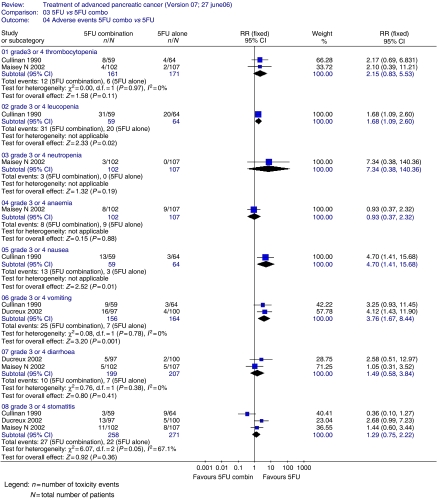

Two trials assessed TTP (Figure 1) and found no significant advantage for 5FU combinations over 5FU alone (HR=1.02; 95% CI=0.85–1.23). For PFS, 5FU combination appeared better than 5FU alone (two trials; 416 patients; HR=0.67; 95% CI=0.46–0.98). The ORR (Figure 2) was superior (five trials; 700 patients; RR=0.43; 95% CI=0.25–0.74) in the 5FU combination arm. Grade 3 or 4 vomiting was significantly greater in the 5FU combination chemotherapy arm (two trials; 320 patients; RR=3.76; 95% CI=1.67–8.44). There was a higher occurrence of diarrhoea (two trials 406 patients; RR=1.49; 95% CI=0.58–3.84), stomatitis (three trials; 529 patients; RR=1.29; 95% CI=0.75–2.22) and thrombocytopenia (two trials; 332 patients; RR=2.15; 95% CI=0.83–5.53) in the combination chemotherapy arm (Figure 3). Data for leucopenia, neutropenia, anaemia and nausea are displayed in Figure 3. There was significant between trial heterogeneity in the PFS analysis, unlike for the TTP and response rate analyses.

Figure 1.

5FU single agent vs 5FU-based combination chemotherapy – PFS/TTP analyses.

Figure 2.

5FU single agent vs 5FU-based combination chemotherapy – response rate analyses.

Figure 3.

5FU single agent vs 5FU-based combination chemotherapy – toxicity analyses.

Gemcitabine vs 5FU

Two randomised controlled trials involving 197 patients were assessed (Burris et al, 1997; Cantore et al, 2004), including unpublished individual patient data (Cantore et al, 2004). A HR of <1 indicates a survival advantage for gemcitabine. Gemcitabine resulted in survival advantage on TTP analysis, (HR=0.46; 95% CI=0.31–0.70), but not for PFS analysis (HR=0.94; 95% CI=0.58–1.53).

Overall response rate appeared better in the gemcitabine arm; however, the wide confidence interval suggests a benefit for either gemcitabine or 5FU (one trial; 126 patients; RR=0.14; 95% CI=0.01–2.66). In the Burris trial (Burris et al, 1997), haematological toxicity was seen more frequently following gemcitabine therapy (grades 3 and 4 neutropenia in 25% of gemcitabine and 4.9% of 5FU patients; P<0.001).

Gemcitabine vs gemcitabine-based combination chemotherapy

Nineteen studies involving 4697 patients were included (Supplementary Table 2) (Berlin et al, 2002; Colucci et al, 2002; Wang et al, 2002; Heinemann et al, 2003; Scheithauer et al, 2003; Li and Chao, 2004; Ohkawa, 2004; Rocha Lima et al, 2004; Viret et al, 2004; Cunningham et al, 2005; Di Costanzo et al, 2005; Hermann et al, 2005; Louvet et al, 2005; Oettle et al, 2005; Reiss et al, 2005; Reni et al, 2005; Stathopoulos et al, 2005; Abou-Alfa et al, 2006; Poplin et al, 2006). Data from four of the included studies (Abou-Alfa et al, 2006; Heinemann et al, 2006b; Stathopoulos et al, 2006; Herrmann et al, 2007) were based on abstracts and extra data provided by the authors (Hermann et al, 2005; Stathopoulos et al, 2005). A HR of <1 indicates a survival advantage for gemcitabine-based combination chemotherapy.

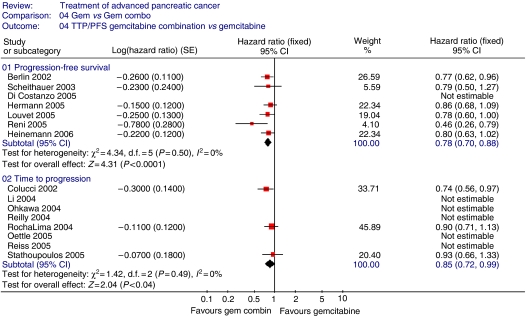

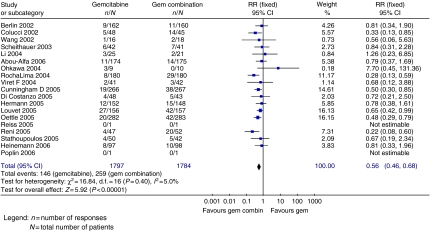

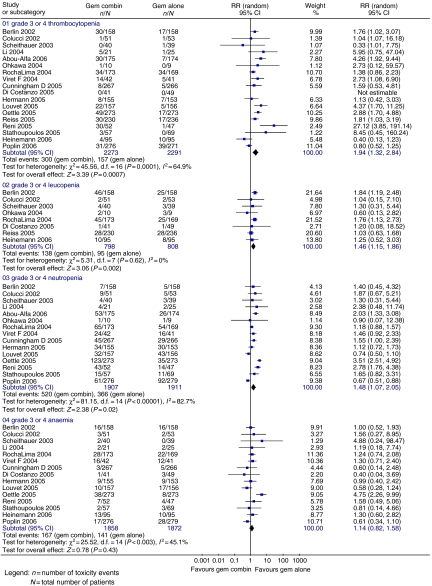

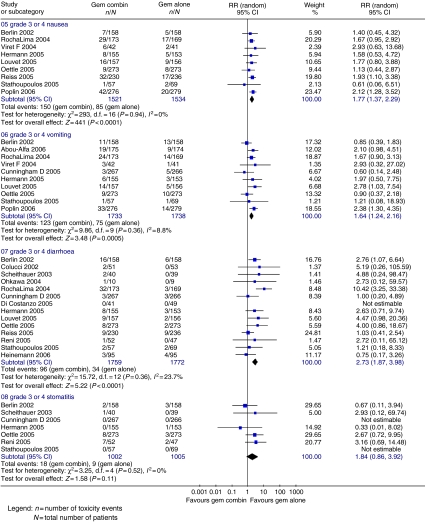

Progression-free survival (four trials; 864 patients; HR=0.78; 95% CI=0.70–0.88), TTP (3 trials; 559 patients; HR=0.85; 95% CI=0.72–0.99) (Figure 4) and ORR (Figure 5) (17 trials; 3577 patients; RR=0.56; 95% CI=0.46–0.68) were significantly better in the gemcitabine combination chemotherapy arm. Haematological toxicity was greater in the gemcitabine combination chemotherapy arm (Figure 6), including thrombocytopenia (18 trials; 4564 patients; RR=1.94; 95% CI=1.32–2.84), leucopenia (eight trials; 1606 patients; RR=1.46; 95% CI=1.15–1.86), neutropenia (15 trials; 3818 patients; RR=1.48; 95% CI=1.07–2.05) and anaemia (15 trials; 3745 patients; RR=1.14; 95% CI=0.82–1.59). Gastrointestinal side effects (Figure 7) of nausea (nine trials; 3055 patients; RR=1.77; 95% CI=1.37–2.29), vomiting (10 trials; 3471 patients; RR=1.64; 95% CI=1.24–2.16) and diarrhoea (14 trials; 3531 patients; RR=2.73; 95% CI=1.87–3.98) were significantly increased, with a trend towards increased stomatitis (7 trials; 2007 patients; RR=1.84; 95% CI=0.86–3.92) in the gemcitabine combination chemotherapy arm. There was no significant inter-trial heterogeneity for the end points of PFS, TTP and ORR.

Figure 4.

Results for gemcitabine vs gemcitabine-based combination chemotherapy – TTP/PFS.

Figure 5.

Results for gemcitabine vs gemcitabine-based combination chemotherapy – response rate.

Figure 6.

Results for gemcitabine vs gemcitabine-based combination chemotherapy – haematological toxicity.

Figure 7.

Results for gemcitabine vs gemcitabine-based combination chemotherapy – gastrointestinal toxicity.

Examination of the funnel plots revealed evidence of bias, possibly publication bias, but this is difficult to interpret in view of the small number of studies within each comparison.

Discussion

5FU combinations did not prolong TTP over 5FU alone, despite significantly better response rate with the former. The study of Yip et al (2006) assessed the parameters described in our analyses, but did not pool the results unlike our approach. In the two trials that had assessed PFS, the overall summary estimate favoured 5FU combination chemotherapy, but there was significant inter-trial heterogeneity. This may be due to the differences in dosing. The dose of 5FU administered was lower in the Maisey et al (2002) study (300 mg m−2 day−1 in both arms) compared to the Ducreux et al (2002) study (500 mg m−2 day−1 used in the single-agent arm and 1000 mg m−2 used in the combination arm).

As overall survival is a better indicator of efficacy than response rate (Maisey et al, 2002), the evidence from these end points, interpreted alongside the overall survival result (Sultana et al, 2007), do not support the use of 5FU combinations over 5FU single agent.

Meta-analyses of the secondary end points were not possible in the gemcitabine vs 5FU comparison, as these results were only available for one randomised trial.

Previous meta-analyses of secondary end points evaluating gemcitabine-based combinations vs gemcitabine employed differing survival analyses methodology (Liang, 2005; Heinemann et al, 2006a; Milella et al, 2006; Xie et al, 2006a). In contrast to these reports, our survival analyses were conducted using the HR, which is the ideal measure for time-to-event analyses, as it accounts for both censoring of data and the time it takes for the event (such as death or progression) to occur (Parmar et al, 1998).

For gemcitabine-based chemotherapy vs gemcitabine alone, our findings of improved PFS/TTP are in agreement with the meta-analyses of Xie et al (2006b). Better ORR with the combination regimens was in keeping with the studies of Xie et al and Milella et al (Xie et al, 2006b), while increased toxicity profile was noted by Xie et al (2006b). The meta-analyses that examined gemcitabine plus a platinum agent vs gemcitabine alone found better PFS/TTP in the combination arm (Xie et al, 2006a; Heinemann et al, 2007), significant improvement in ORR (Heinemann et al, 2007) and greater toxicity (Xie et al, 2006a).

We have done our utmost to cover most reported end points in the randomised controlled trials. We could not address quality of life due to the different methods used for reporting quality of life. Although we have pooled the response rate and adverse events data across studies to permit a clinically relevant analysis, reporting of these parameters varied. Response rates were reported using clinical parameters, the WHO and RECIST criteria, whereas the CTC, WHO and ECOG scales were used for toxicity data.

To conclude, there is insufficient evidence to suggest a TTP, response rate and toxicity advantage in administering 5FU in combination with other chemotherapy agents over 5FU alone. There is a small but significant TTP/PFS advantage, as well as improved response rate, with gemcitabine-based combinations, and this provides a justification for the use of these agents, despite their greater toxicity. An area for further randomised controlled trials to assess is which gemcitabine-based combination chemotherapy regimens are least toxic, while retaining all the other advantages of the combination approach.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by Cancer Research UK.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on British Journal of Cancer website (http://www.nature.com/bjc)

Supplementary Material

References

- Abou-Alfa GK, Letourneau R, Harker G, Modiano M, Hurwitz H, Tchekmedyian NS, Feit K, Ackerman J, De Jager RL, Eckhardt SG, O'Reilly EM (2006) Randomised phase III study of exatecan and gemcitabine compared with gemcitabine alone in untreated advanced pancreatic cancer. J Clin Oncol 24: 4441–4447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berlin JD, Catalano P, Thomas JP, Kugler JW, Haller DG, Benson III AB (2002) Phase III study of gemcitabine in combination with fluorouracil vs gemcitabine alone in patients with advanced pancreatic carcinoma: Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Trial E2297. J Clin Oncol 20: 3270–3275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bria E, Milella M, Gelibter A, Cuppone F, Pino MS, Ruggeri EM, Carlini P, Nisticò C, Terzoli E, Cognetti F, Giannarelli D (2007) Gemcitabine-based combinations for inoperable pancreatic cancer: have we made real progress? A meta-analysis of 20 phase 3 trials. Cancer 110: 525–533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burris H, Moore M, Andersen J, Green MR, Rothenberg ML, Modiano MR, Cripps MC, Portenoy RK, Storniolo AM, Tarassoff P, Nelson R, Dorr FA, Stephens CD, Von Hoff DD (1997) Improvements in survival and clinical benefit with gemcitabine as first-line therapy for patients with advanced pancreas cancer: a randomised trial. J Clin Oncol 15: 2403–2413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cancer Research UK (2006) Cancer Stats Incidence, http://info.cancerresearchuk.org/cancerstats

- Cantore M, Fiorentini G, Luppi G, Rosati G, Caudana R, Piazza E, Comella G, Ceravolo C, Miserocchi L, Mambrini A, Del Freo A, Zamagni D, Rabbi C, Marangolo M (2004) Gemcitabine vs FLEC regimen given intra-arterially to patients with unresectable pancreatic cancer: a prospective, randomised phase III trial of the Italian Society for Integrated Locoregional Therapy in Oncology. J Chemother 16: 589–594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colucci G, Giuliani F, Gebbia V, Biglietto M, Rabitti P, Uomo G, Cigolari S, Testa A, Maiello E, Lopez M (2002) Gemcitabine alone or with cisplatin for the treatment of patients with locally advanced and/or metastastic pancreatic carcinoma. A prospective, randomised phase III study of the Gruppo Oncologico dell'Italia Meridionale. Cancer 94: 902–910 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cullinan SA, Moertel CG, Fleming TR, Rubin JR, Krook JE, Everson LK, Windschitl HE, Twito DI, Marschke RF, Foley JF, Pfeifle DM, Barlow JF (1985) A comparison of three chemotherapeutic regimens in the treatment of advanced pancreatic and gastric carcinoma. Fluorouracil vs fluorouracil and doxorubicin vs fluorouracil, doxorubicin, and mitomycin. JAMA 253: 2061–2067 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cullinan S, Moertel C, Wieand H, Schutt AJ, Krook JE, Foley JF, Norris BD, Kardinal CG, Tschetter LK, Barlow JF (1990) A phase III trial on therapy of advanced pancreatic carcinoma. Cancer 65: 2207–2212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham D, Chau I, Stocken D, Davies C, Dunn J, Valle J, Smith D, Steward W, Harper P, Neoptolemos JP (2005) Phase III randomised comparison of gemcitabine vs gemcitabine plus capecitabine in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer. Eur J Can Supplements 3: 4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deeks J, Altman D, Bradburn M (2001) Statistical methods for examining heterogeneity and combining results from several studies in meta-analysis. In Systematic reviews in Health Care. Meta-analysis in context, Egger M, Smith G, Altman D (eds), pp 285–312. BMJ Publishing Group: London [Google Scholar]

- Deeks J, Higgins J, Altman D (2004) Analysing and presenting results. In Cochrane Reviewers Handbook 4.2.2 [updated March 2004]. Section 8 pp www.cochrane.org/resources/handbook/hbook.htm

- Di Costanzo F, Carlini P, Doni L, Massidda B, Mattioli R, Iop A, Barletta E, Moscetti L, Recchia F, Tralongo P, Gasperoni S (2005) Gemcitabine with or without continuous infusion 5-FU in advanced pancreatic cancer: a randomised phase II trial of the Italian oncology group for clinical research (GOIRC). Br J Cancer 93: 185–189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ducreux M, Rougier P, Pignon J-P, Douillard JY, Seitz JF, Bugat R, Bosset JF, Merouche Y, Raoul JL, Ychou M, Adenis A, Berthault-Cvitkovic F, Luboinski M, Groupe Digestif of the Fédération Nationale des Centres de Lutte Contre le Cancer Digestif (2002) A randomised trial comparing 5-FU with 5-FU plus cisplatin in advanced pancreatic carcinoma. Ann Oncol 13: 1185–1191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fung M, Takayama S, Ishiguro H, Sakata T, Adachi S, Morizane T (2003) Chemotherapy for advanced or metastatic pancreatic cancer: analysis of 43 randomised trials in 3 decades (1974–2002). Gan To Kagaku Ryoho 30: 1101–1111 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinemann V, Labianca R, Hinke A, Louvet C (2007) Increased survival using platinum analog combined with gemcitabine as compared to single-agent gemcitabine in advanced pancreatic cancer: pooled analysis of two randomised trials, the GERCOR/GISCAD intergroup study and a German multicentre study. Ann Oncol 18: 1652–1659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinemann V, Labianca R, Hinke A, Louvet C (2006a) Superiority of gemcitabine plus platinum analog compared to gemcitabine alone in advanced pancreatic cancer: Pooled analysis of two randomised trials, the GERCOR/GISCAD Intergroup Study and a German Multicenter Study. In 2006 Gastrointestinal Cancers Symposium, pp. Abstract 96

- Heinemann V, Quietzsch D, Gieseler F, Gonnermann M, Schonekas H, Rost A, Neuhaus H, Haag C, Stoffregen C, Clemens M (2003) A phase III trial comparing gemcitabine plus cisplatin vs gemcitabine alone in advanced pancreatic carcinoma. In ASCO Annual Meeting, pp. Abstract no. 1003

- Heinemann V, Quietzsch D, Gieseler F, Gonnermann M, Schönekäs H, Rost A, Neuhaus H, Haag C, Clemens M, Heinrich B, Vehling-Kaiser U, Fuchs M, Fleckenstein D, Gesierich W, Uthgenannt D, Einsele H, Holstege A, Hinke A, Schalhorn A, Wilkowski R (2006b) Randomised phase III trial of gemcitabine plus cisplatin compared with gemcitabine alone in advanced pancreatic cancer. J Clin Oncol 24: 3946–3952 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermann R, Bodoky G, Ruhstaller T, Glimelius B, Saletti P, Bajetta E, Schueller J, Bernhard J, Dietrich D, Scheithauer W (2005) Gemcitabine plus capecitabine vs gemcitabine alone in locally advanced or metastatic pancreatic cancer. A randomised phase III study of the Swiss Group for Clinical Cancer Research (SAKK) and the Central European Cooperative Oncology Group (CECOG). In 2005 ASCO Annual Meeting, pp. Abstract no. LBA4010: Orlando: USA

- Herrmann R, Bodoky G, Ruhstaller T, Glimelius B, Glimelius B, Bajetta E, Schüller J, Saletti P, Bauer J, Figer A, Pestalozzi B, Köhne CH, Mingrone W, Stemmer SM, Tàmas K, Kornek GV, Koeberle D, Cina S, Bernhard J, Dietrich D, Scheithauer W (2007) Gemcitabine plus capecitabine compared with gemcitabine alone in advanced pancreatic cancer: a randomised, multicenter, phase III trial of the Swiss Group for Clinical Cancer Research and the Central European Cooperative Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol 25: 2159–2161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovach J, Moertel C, Schutt A, Hahn RG, Reitemeier RJ (1974) A controlled study of combined 1,3 bis-(2-chloroethyl)-1-nitrosourea and 5-fluorouracil therapy for advanced gastric and pancreatic cancer. Cancer 33: 563–567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C-P, Chao Y (2004) A prospective randomised trial of gemcitabine alone or gemcitabine+cisplatin in the treatment of metastatic pancreatic cancer. In 2004 ASCO Annual Meeting, pp. Abstract no. 4144

- Liang H (2005) Comparing gemcitabine-based combination chemotherapy with gemcitabine alone in inoperable pancreatic cancer: A meta-analysis. In 2005 ASCO Annual Meeting, pp. abstract nox 4110: Orlando: USA

- Louvet C, Labianca R, Hammel P, Lledo G, Zampino MG, André T, Zaniboni A, Ducreux M, Aitini E, Taïeb J, Faroux R, Lepere C, de Gramont A (2005) Gemcitabine in combination with oxaliplatin compared with gemcitabine alone in locally advanced or metastatic pancreatic cancer: Results of a GERCOR and GISCAD phase III trial. J Clin Oncol 23: 3509–3516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maisey N, Chau I, Cunningham D, Norman A, Seymour M, Hickish T, Iveson T, O′Brien M, Tebbutt N, Harrington A, Hill M (2002) Multicenter randomised phase III trial comparing protracted infusion 5-Fluorouracil with PVI 5-FU plus mitomycin in inoperable pancreatic cancer. J Clin Oncol 20: 3130–3136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mancuso A, Calabro F, Sternberg CN (2006) Current therapies and advances in the treatment of pancreatic cancer. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 58: 231–241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milella M, Carlini P, Gelibter A, Ruggeri E, Ceribelli A, Pino M, Terzoli E, Cognetti F, Giannarelli D, Bria E (2006) Gemcitabine-based polychemotherapy for advanced pancreatic cancer (APC): is it ready for prime time? A pooled analysis of 3682 patients (pts) enrolled in 12 phase III trials. J Clin Oncol 24: 4118 [Google Scholar]

- Oettle H, Richards D, Ramanathan R, van Laethem JL, Peeters M, Fuchs M, Zimmermann A, John W, Von Hoff D, Arning M, Kindler HL (2005) A phase III trial of pemetrexed plus gemcitabine vs gemcitabine in patients with unresectable or metastatic pancreatic cancer. Ann Oncol 16: 1639–1645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohkawa S (2004) Randomised controlled trial of gemcitabine in combination with UFT vs gemcitabine alone in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer. J Clin Oncol 22: 4131 [Google Scholar]

- Parmar M, Torri V, Stewart L (1998) Extracting summary statistics to perform meta-analyses of the published literature for survival endpoints. Stat Med 17: 2815–2834 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul S, Donner A (1992) Small sample performance of tests of homogeneity of odds ratios in K 2 × 2 table. Stat Med 11: 159–165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poplin E, Levy D, Berlin J, Rothenberg M, Cella D, Mitchell E, Alberts S, Benson A (2006) Phase III trial of gemcitabine (30-min infusion) vs gemcitabine (fixed-dose rate infusion) vs gemcitabine + oxaliplatin in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer (E6201). J Clin Oncol 24: LBA4004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiss H, Helm A, Niedergethmann M, Schmidt-Wolf I, Moik M, Hammer C, Zippel K, Weigang-Köhler K, Stauch M, Oettle H, Deutsche Krebsgesellschaft (2005) A randomised, prospective, multicentre, phase III trial of gemcitabine, 5-Fluorouracil, folinic acid vs gemcitabine alone in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer. In ASCO Annual Meeting, pp. Abstract no. LBA4009

- Reni M, Cordio S, Milandri C, Passoni P, Bonetto E, Oliani C, Luppi G, Nicoletti R, Galli L, Bordonaro R, Passardi A, Zerbi A, Balzano G, Aldrighetti L, Staudacher C, Villa E, Di Carlo V (2005) Gemcitabine vs cisplatin, epirubicin, fluorouracil, and gemcitabine in advanced pancreatic cancer: a randomised controlled multicentre phase III trial. Lancet Oncol 6: 369–376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rocha Lima C, Flores A (2006) Gemcitabine doublets in advanced pancreatic cancer: Should we move on? J Clin Oncol 24: 327–329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rocha Lima C, Green M, Rotche R, Miller Jr WH, Jeffrey GM, Cisar LA, Morganti A, Orlando N, Gruia G, Miller LL (2004) Irinotecan plus gemcitabine results in no survival advantage compared with gemcitabine monotherapy in patients with locally advanced or metastatic pancreatic cancer despite increased tumor response rate. J Clin Oncol 22: 3776–3783 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheithauer W, Schull B, Ulrich-Pur H, Schmid K, Raderer M, Haider K, Kwasny W, Depisch D, Schneeweiss B, Lang F, Kornek GV (2003) Biweekly high-dose gemcitabine alone or in combination with capecitabine in patients with metastastic pancreatic adenocarcinoma: a randomised phase II trial. Ann Oncol 14: 97–104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stathopoulos G, Aravantinos G, Syrigos K, Kalbakis K, Karvounis N, Papakotoulas P, Boukovinas J, Potamianou A, Polyzos A, Christophillakis C, Georgoulias V (2005) A randomised phase III study of irinotecan/gemcitabine combination vs gemcitabine in patients with advanced/metastatic pancreatic cancer. In 2005 ASCO Annual Meeting, pp. Abstract no. 4106: Orlando: USA

- Stathopoulos G, Syrigos K, Aravantinos G, Polyzos A, Papakotoulas P, Fountzilas G, Potamianou A, Ziras N, Boukovinas J, Varthalitis J, Androulakis N, Kotsakis A, Samonis G, Georgoulias V (2006) A multicentre phase III trial comparing irinotecan-gemcitabine with gemcitabine monotherapy as first-line treatment in patients with locally advanced or metastatic pancreatic cancer. Br J Cancer 95: 587–592 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sultana A, Tudur Smith C, Cunningham D, Starling N, Neoptolemos J, Ghaneh P (2007) Meta-analyses of chemotherapy for locally advanced and metastatic pancreatic cancer. J Clin Oncol 25: 2607–2615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viret F, Ychou D, Lepille L, Mineur L, Navarro F, Topart D, Fonck M, Goineau J, Madroszyk-Flandin A, Chouaki N (2004) Gemcitabine in combination with cisplatin vs gemcitabine alone in the treatment of locally advanced or metastatic pancreatic cancer: Final results of a multicentre randomised phase II study. J Clin Oncol 22: 4118 [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Ni Q, Jin M, Li Z, Wu Y, Zhao Y, Feng F (2002) Gemcitabine or gemcitabine plus cisplatin in 42 patients with locally advanced or metastatic pancreatic cancer. Chin J Oncol 24: 404–407 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson P, Smith C, Hutton J, Marson A (2002) Aggregate data meta-analysis with time-to-event outcome. Stat Med 21: 3337–3351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie D, Liang H, Wang Y, Guo S (2006a) Meta-analysis of inoperable pancreatic cancer: gemcitabine combined with cisplatin vs gemcitabine alone. Chin J Dig Dis 7: 49–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie D, Liang H, Wang Y, Guo S, Yang Q (2006b) Meta-analysis on inoperable pancreatic cancer: a comparison between gemcitabine-based combination therapy and gemcitabine alone. World J Gastroenterol 12: 6973–6981 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yip D, Karapetis C, Strickland A, Steer C, Goldstein D (2006) Chemotherapy and radiotherapy for inoperable pancreatic cancer. In Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Vol. 3 issue 3, art. no. CD002093. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD002093.pub2 [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.