Abstract

Because the role of regulatory T cells in the intestinal inflammation is unknown in coeliac disease (CD) and type 1 diabetes (T1D), the expression of forkhead box P3 (FoxP3), CD25, transforming growth factor-β, interferon (IFN)-γ, interleukin (IL)-4, IL-8, IL-10, IL-15 and IL-18 was measured by quantitative reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction in the small intestinal biopsies from paediatric patients with active or potential CD, T1D and control patients. The numbers of FoxP3- and CD25-expressing cells were studied with immunohistochemistry. Enhanced intestinal expressions of FoxP3, IL-10 and IFN-γ mRNAs were found in active CD when compared with controls (P-values < 0·001, 0·004, <0·001). In potential CD, only the expression of IFN-γ mRNA was increased. The numbers of FoxP3-expressing cells were higher in active and potential CD (P < 0·001, P = 0·05), and the ratio of FoxP3 mRNA to the number of FoxP3-positive cells was decreased in potential CD when compared with controls (P = 0·007). The ratio of IFN-γ to FoxP3-specific mRNA was increased in active and potential CD (P = 0·001 and P = 0·002). Patients with T1D had no changes in regulatory T cell markers, but showed increased expression of IL-18 mRNA. The impaired up-regulation of FoxP3 transcripts despite the infiltration of FoxP3-positive cells in potential CD may contribute to the persistence of inflammation. The increased ratio of IFN-γ to FoxP3 mRNA in active and potential CD suggests an imbalance between regulatory and effector mechanisms. The increased intestinal expression of IL-18 mRNA in patients with T1D adds evidence in favour of the hypothesis that T1D is associated with derangements in the gut immune system.

Keywords: coeliac disease, FoxP3, gut, regulatory T cells, type 1 diabetes

Introduction

The first lesion to develop in coeliac disease (CD) is inflammation in the intraepithelial space of the small intestine: both CD8+ effector cells and particularly T cell receptor (TCR) γ/δ-expressing cells are increased [1]. Toxic gliadin peptides may activate the innate immune system by up-regulating interleukin (IL)-15 secretion [2], which again leads to massive expansion of TCR α/β-positive T cells [3]. When gliadin is withdrawn from the diet this process stops and the infiltration of TCR α/β-positive T cells is normalized, but that of TCR γ/δ-positive T cells is preserved for years [4]. The entry of increased amounts of toxic gliadin peptides into lamina propria activates a specific immune reaction to these peptides in CD. Tissue transglutaminase deamidated gliadin-derived peptides bind specifically CD-associated human leucocyte antigen DQ2-related (HLA-DQ2) and HLA-DQ8 heterodimers on antigen-presenting cells, and this leads to activation of CD4+ cells in the lamina propria of the jejunum [4]. Type 1 immune reactions develop with secretion of inflammatory cytokines, interferon (IFN)-γ and tumour necrosis factor-α, increasing further the expression of HLA-class II antigen and the permeability of the intestine [5–7]. Simultaneously, CD4+ cells activate B cells to produce autoimmune antibodies to the complex of gliadin peptides and tissue transglutaminases. Immunoglobulin A (IgA) isotype antibodies recognizing tissue transglutaminase are highly specific for CD [8]. Finally, villous atrophy develops during continued ingestion of gluten [8]. The abortive disease in an individual who has the CD-associated DQ2 or DQ8 alleles, characterized by the infiltrative lesion of high numbers of intraepithelial lymphocytes (IEL), particularly those with TCR γ/δ, and the presence of autoimmune antibodies, is called potential CD [1]. When screening for CD among family members of patients, such abortive cases are often found. Factors precipitating full-blown morphological disease in these individuals are not known.

Involvement of the gut immune system has been suggested to be associated with the pathogenesis of type 1 diabetes (T1D), another autoimmune disease in which beta-cell destruction is considered to be T helper 1-mediated. In contrast to CD, the external antigens possibly initiating the autoimmune process are unknown, but many links between CD and T1D exist: the prevalence of CD is three times higher in patients with T1D than in the general population [9], probably because of the shared risk allele, HLA-DQ2. Some patients with T1D and without CD, however, show increased immune response to wheat proteins: gluten [10], storage globulin [11] and gliadin [12].

We have reported previously enhanced immune activation in small intestinal biopsies of patients with T1D, such as increased numbers of HLA class II-, IL-1α- and IL-4-positive cells [13].

A key role for so-called regulatory T cells has been indicated in control of the immune response to self and non-self. Regulatory T cells expressing CD4, high-intensity CD25 and transcription factor forkhead box P3 (FoxP3) are able to suppress the activation of effector T cells [14,15]. The role of intestinal regulatory T cells is not known in CD or in T1D. Our aim was to evaluate the balance of regulatory and effector cells in different stages of CD, acute versus potential, and in T1D, in which the activation of intestinal immune system is often seen without tissue destruction. For this study we examined small intestinal biopsy specimens from children and adolescents with active, untreated CD or with potential CD (normal villous structure and increased density of IEL and/or presence of CD-associated antibodies) with and without T1D, from patients with T1D or from controls. We studied mRNA for a panel of cytokines, namely IL-4, IL-8, IL-10, IL-15, IL-18, IFN-γ, transforming growth factor (TGF)-β, and for transcription factor FoxP3 and CD25. We also measured the densities of FoxP3- and CD25-positive cells by means of immunohistochemistry.

Materials and methods

Subjects

Small intestinal biopsy specimens were obtained from 65 paediatric patients. Some specimens were taken by a Watson capsule from the proximal jejunum of the distal duodenum and some during gastroduodenoscopy from the distal duodenum. The specimens were divided for routine histology and immunohistochemical and reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT–PCR) studies. The part for immunohistochemistry and RT–PCR was embedded in optimal cutting temperature compound (Miles Laboratories, Elkhart, IN, USA), snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −70°C until used. The specimens for routine histology were embedded in paraffin.

We studied 15 patients with active, untreated CD having villous atrophy and crypt hyperplasia (10 girls; mean age 7·0 years, range 1·2–12·6 years), and seven patients (two girls; mean age 8·9 years, range 4·0–15·2 years) with increased density of TCR γ/δ-expressing IEL and/or CD-associated antibodies indicating potential CD.

Twenty-nine patients suffered from T1D. Patients with T1D were followed-up at the out-patient clinic of the Hospital for Children and Adolescents, University of Helsinki. Because of positive findings in the annual CD screening test, including IgA and IgG gliadin, IgA endomysium and tissue-transglutaminase antibodies, or because of gastrointestinal symptoms, a small intestinal biopsy specimen was obtained. The patients with T1D fell subsequently into three groups: 12 patients had villous atrophy with crypt hyperplasia and infiltrative changes and thus had active CD (seven girls; mean age 7·7 years, range 3·3–14·3 years). Eight patients (four girls; mean age 8·1 years, range 4·5–15·0 years) had normal villous structure but had elevated density of IEL and/or presence of CD-associated autoantibodies. Nine showed normal villous structure and normal density of IEL (five girls; mean age 10·6 years, range 3·5–18·2 years). The diagnosis of CD was set according to the European Society of Paediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition criteria [16].

In addition, 14 age-matched patients without autoimmune diseases and with normal small intestinal mucosa were studied as a control group (seven girls; mean age 6·2 years, range 1·1–14·1 years). The biopsies were performed because of growth retardation, gastrointestinal symptoms, positive anti-gliadin antibodies, or any combination of these. The controls had no history of CD in the family, they were not on medication and did not have chronic diseases. The morphology of the small intestinum was normal and the endomysium and tissue transglutaminase antibodies were negative in all control patients. Every patient included in this study had a medical indication for taking the small intestinal biopsy specimen. The use of biopsy specimens for this study was approved by the ethics committee of the Hospital for Children and Adolescents, University of Helsinki, Finland. The study plan was explained orally and a written consent was signed by the parents of the children.

Real-time quantitative RT–PCR

The protocol for real-time quantitative RT–PCR analysis of mRNA levels in the small intestinal biopsies was performed as described previosly [13]. Total RNA was extracted from homogenized mucosal biopsies with the GenElute Mammalian Total RNA Miniprep kit (Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA). RT was performed using TaqMan RT reagents (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA), including pretreatment with DNase (Boehringer Mannheim, Mannheim, Germany).

Real-time quantitative PCR was performed using TaqMan predeveloped assay reagents (PDAR) or assays-on-demand primers/probes and the ABI-Prism 7700 Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems) in triplicate wells. PDAR primers/probes for CD25 (cat. no. 4328847F), IL-18 (cat. no. 4327049F), IL-15 (cat. no. 4327047F), IL-8 (cat. no. 4327042F), IL-6 (cat. no. 4327040F), TGF-β (cat. no. 4327054), IFN-γ (cat. no. 4327052), IL-4 (cat no. 4327038) and IL-10 (cat no. 4327043F) were used. For FoxP3 assays-on-demand primer/probe (cat. no. Hs00203958_m1) was used. Ribosomal 18S RNA was used as an endogenous control (for PDAR reactions 4310893E and for assays-on-demand reactions Hs99999901_s1). In every plate the expression of the same marker mRNA was measured in a calibrator sample, which was prepared from phytohaemagglutinin (Sigma)-stimulated peripheral blood mononuclear cells from a healthy volunteer.

The quantities of the markers were analysed by a comparative threshold cycle (CT) method. The quantitative value obtained from the TaqMan run is a CT, which indicates the number of PCR cycles at which the amount of amplified target molecule exceeds a predefined fluorescence threshold value. The difference value (ΔCT) is the normalized quantitative value of the expression level of the target gene achieved by subtracting the CT value of the housekeeping gene (18S) from the CT value of the target gene. An exogenous cDNA pool calibrator performed from mitogen-stimulated human peripheral blood mononuclear cells was considered as an interassay standard to which normalized samples were compared. Calculations are expressed as follows: ΔΔCT(sample) = ΔCT(sample) − ΔCT (calibrator). The difference in expression level is given by: 2-ΔΔCT. ΔCT stands for the difference between CT of the marker gene and CT of the 18S gene, whereas ΔΔCT is the difference between ΔCT of the analysed sample and ΔCT of the calibrator. Calculation of 2–ΔΔCT then gives a relative amount of the analysed sample compared with the calibrator, both normalized to an endogenous control (18S). The relative amounts (2–ΔΔCT) of CD25, IL-8, IL-6 and IFN-γ were multiplied by 1000, the relative amounts of TGF-β, IL-10 and FoxP3 by 100, the relative amount of IL-4 by 10 and the relative amount of IL-18 by 1 × 10−1 to obtain whole numbers for plots.

Immunohistochemistry

The avidin–biotin immunoperoxidase system was used on cryostat sections to stain IEL (CD3 and TCR γ/δ) as described previously [17]. When this staining was performed we homogenized the remaining part of the specimen for mRNA measurements. Therefore, for immunostainingof FoxP3 and CD25, paraffin serial sections were used. Paraffin slides were deparaffinized and antigen retrieval was performed by microwave cooking for 20 min in 10 mM citrate buffer (pH 6·0) for FoxP3 and for 3 min in 2 mM ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid and 50 mM Tris (pH 9·0) for CD25. Endogenous peroxidase activity was quenched by incubating the slides for 30 min at room temperature in 0·5% H2O2 in methanol. Following blocking with 1% normal horse sera (Vectastain Elite ABC Kit; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) for 30 min the sections were incubated with the primary monoclonal mouse anti-human antibodies for 1 h at room temperature. The antibodies were diluted in 1% normal horse sera and the final concentrations were as follows: FoxP3 (1:40) 10 μg/ml (clone 236 A/E7; Abcam, Cambridge, UK) and CD25 (1:10) 7·4 μg/ml (clone ACT-1; Dakocytomatin, Glostrup, Denmark). Bound antibody was detected with a commercial avidin–biotin immunoperoxidase system (Vectastain Elite ABC kit) according to the manufacturer's instructions, using 3,3′-diaminobenzidine chromogen (DAB; Sigma) as substrate. The slides were counterstained with haematoxylin.

Double immunostaining for CD25 and FoxP3 was performed as described above, with the following modifications: after staining of CD25 antibody with DAB the slides were incubated with FoxP3 antibody over night at +4°C. Bound FoxP3 antibody was visualized with Vector SG® (Vector Laboratories) as substrate.

Non-immune mouse IgG1 (Dako) was used as negative primary antibody control and incubation with 1% normal horse sera on additional sections as negative control for reagents in the immunoperoxidase system.

Microscopic evaluation

The slides were investigated blinded to the clinical data. The numbers of positively stained mononuclear cells were counted systematically under a light microscope through a calibrated eyepiece graticule at ×1000 magnification, as described previously [17,18]. The positive cells in at least 30–50 fields were counted, either along the surface epithelium or in the lamina propria. The cell densities were expressed as the mean number of positively staining cells/mm of surface epithelium and as cells/mm2 in the lamina propria.

Statistical analysis

The non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis test and Mann–Whitney U-test were used for comparisons between the groups. The Spearman's rank correlation test was applied to analyse correlations between different parameters (spss 10·0 for Windows; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). P-values < 0·05 were considered significant.

Results

mRNA expression levels

The six groups of paediatric patients differed significantly in their mRNA expression of FoxP3, IL-10, IFN-γ, CD25 and IL-18 (using the Kruskal–Wallis test, P < 0·001 for IL-10, IFN-γ and IL-18; P = 0·008 for FoxP3 and P = 0·023 for CD25). The mRNA expression of TGF-β, IL-4, IL-6, IL-8 and IL-15 did not differ between the groups (data not shown). The median levels of IL-15 mRNA were 18·8 (range 6·6–42·9) for controls and 8·5 (range 2·6–31·3) for patients with CD, and 18·8 (range 11·4–38·9) for patients with T1D.

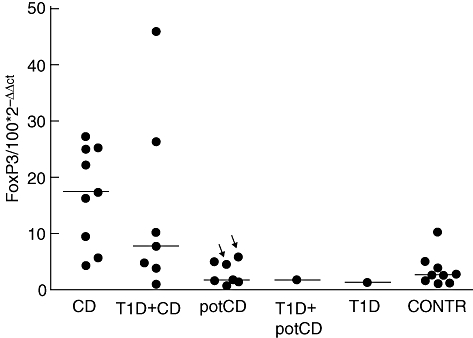

The quantity of FoxP3 mRNA was increased in patients with CD compared with patients with potential CD and compared with control patients with normal mucosa (P = 0·002 and P < 0·001, respectively, using the Mann–Whitney U-test) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Expression of forkhead box P3 (FoxP3)-specific mRNAs detected by reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction in small intestinal mucosa. The expression level of mRNA is shown as relative units (100 × 2−ΔΔCt) in the gut biopsy compared with the calibrator, both normalized to an endogenous control. The median expressions are marked with horizontal lines. The arrows indicate those patients with potential coeliac disease (potCD) who were diagnosed later with CD. The CD patients differed significantly from patients with potCD and from control patients (P = 0·002 and P < 0·001, respectively, using the Mann–Whitney U-test). T1D = type 1 diabetes; potCD: potential CD with elevated levels of T cell receptor γ/δ-expressing intraepithelial lymphocytes and/or presence of CD-associated antibodies; CONTR, control group with normal mucosa.

The expression of IL-10 mRNA was also higher in patients with CD than in the other groups of patients (P = 0·040 for CD versus T1D and the CD group, P = 0·001 for CD versus the potential CD group, P = 0·006 for CD versus T1D and potential CD, P = 0·017 for CD versus the T1D group and P = 0·004 for the CD versus control group using the Mann–Whitney U-test).

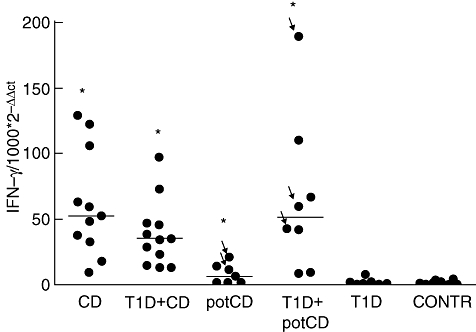

The expression of IFN-γ mRNA was increased in all patients who had CD or potential CD with or without T1D when compared with control patients with normal mucosa (all P-values using the Mann–Whitney U-test were < 0·001, except a P-value of 0·033 for patients with potential CD) (Fig. 2). The patients with T1D without CD or potential CD did not differ from controls.

Fig. 2.

Interferon (IFN)-γ-specific mRNA expressions measured by means of quantitative reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction in small intestinal biopsies. Results are shown as relative amounts (1000 × 2–ΔΔCt). Horizontal lines represent median values of the groups. The arrows indicate those patients with potential coeliac disease (potCD) who were diagnosed later with CD. The patients with CD or with potCD with or without type 1 diabetes (T1D) showed a higher expression of IFN-γ mRNA than the control patients (P < 0·001 for all groups except for patients with potCD, P = 0·033, using the Mann–Whitney U-test). potCD: potential CD with elevated levels of T cell receptor γ/δ-expressing intraepithelial lymphocytes and/or presence of CD-associated antibodies; CONTR, control group with normal mucosa.

The patients with both T1D and CD had a higher expression of CD25 mRNA than the control patients (P = 0·022, using the Mann–Whitney U-test). Otherwise, the expression of CD25 mRNA was greater in patients with CD with or without T1D than in patients with potential CD (P-values were 0·014 and 0·038, respectively, using the Mann–Whitney U-test) or in patients with T1D and normal mucosa (P-values were 0·012 and 0·040, respectively, using the Mann–Whitney U-test).

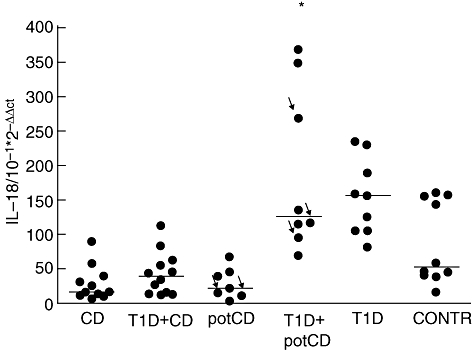

The quantities of IL-18 mRNA were increased in paediatric patients with T1D and normal mucosa compared with control patients with normal mucosa (P = 0·035, using the Mann–Whitney U-test), to patients with CD (P < 0·001), to patients with both T1D and CD (P < 0·001) and to patients with potential CD (P < 0·001) (Fig. 3). Also, the patients with T1D and potential CD had a higher expression of IL-18 mRNA than the patients with CD, patients with T1D and CD and patients with potential CD (all P-values were less than 0·001, using the Mann–Whitney U-test). In patients with CD or with potential CD IL-18 mRNA was expressed at even lower levels than in control patients with normal mucosa (P = 0·004 and P = 0·025 respectively).

Fig. 3.

Interleukin (IL)-18-specific mRNA expression detected by quantitative reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction in small intestinal biopsies. Results are shown as relative amounts (10−1 × 2–ΔΔCt). Horizontal lines show medians for each group. The arrows indicate those patients with potential coeliac disease (potCD) who were diagnosed later with CD. The type 1 diabetes (T1D) patients had higher expression of IL-18 than patients with CD, patients with T1D and CD, patients with potCD (all P-values < 0·001, using the Mann–Whitney U-test) and controls (P = 0·035). The patients with T1D and potCD had a higher expression of IL-18 mRNA than CD patients, patients with T1D and CD and patients with potCD (all P-values < 0·001). IL-18 expression was lower in patients with CD or with potCD compared with control patients (P = 0·004 and P = 0·025). potCD: potential CD with elevated levels of T cell receptor γ/δ-expressing intraepithelial lymphocytes and/or presence of CD-associated antibodies; CONTR, control group with normal mucosa. Here the asterisk indicating the patient groups which differ from controls is only showing the group of T1D plus pot CD but not also the group of T1D as it should.

Correlations between mRNA expression

The expression of IFN-γ mRNA correlated with the mRNA expression of FoxP3 (r = 0·70, P < 0·001), IL-10 (r = 0·62, P < 0·001), TGF-β (r = 0·29, P = 0·027) and CD25 (r = 0·60 and P < 0·001). The expression of IFN-γ mRNA had an inverse correlation with the expression of IL-15 mRNA (r = − 0·37; P = 0·040).

The level of FoxP3 also correlated with the expression of IL-10 (r = 0·51; P = 0·005) and CD25 (r = 0·69, P < 0·001). The expression of TGF-β mRNA, however, did not correlate with the expression of FoxP3 (r = 0·11; P = 0·561).

Furthermore, the quantity of CD25 mRNA correlated with the expression of IL-10 (r = 0·65, P < 0·001) and TGF-β (r = 0·41, P = 0·003) mRNAs.

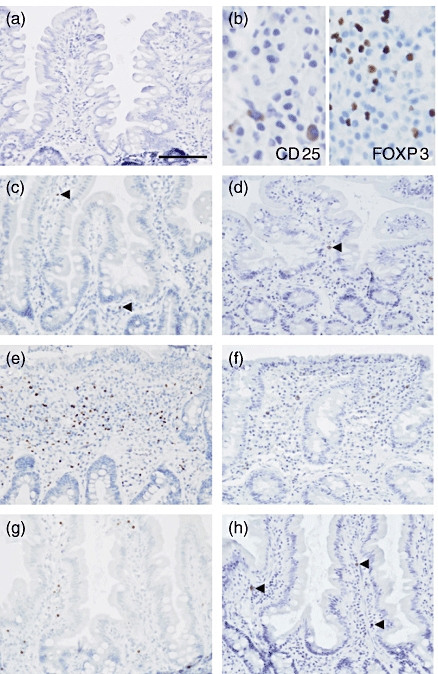

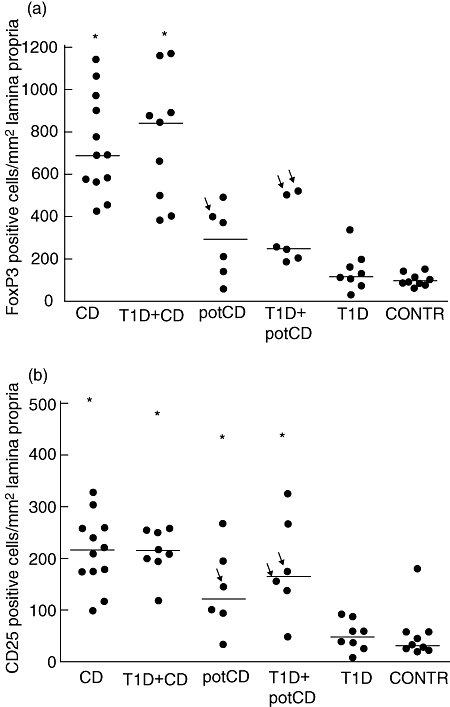

Cells positive for FoxP3 or CD25 by immunohistochemistry

Figure 4 shows examples of immunohistochemical staining of FoxP3 and CD25. Patients with CD and T1D patients with CD had a higher proportion of FoxP3-expressing cells in the lamina propria of small intestine than patients with potential CD (P < 0·001, P = 0·003, respectively, using the Mann–Whitney U-test), patients with T1D and potential CD (P = 0·001, P = 0·012), patients with T1D (P < 0·001, P < 0·001) and control patients (P < 0·001, P < 0·001) (Fig. 5a). Patients with potential CD showed a tendency for increased numbers of FoxP3-expressing cells in lamina propria when compared with controls (P = 0·050).

Fig. 4.

Immunoperoxidase staining for forkhead box P3 (FoxP3) and CD25 in paraffin sections. Representative negative control staining in a normal mucosal biopsy specimen shows no positive staining. 3′3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB)–haematoxylin stain, original magnification × 200 (a). Bar indicates 100 μm. Representative stainings for CD25 (membranous) and FoxP3 (nuclear) are shown at higher magnification in (b). DAB-Vector SG® stain, original magnification × 400 (b). Representative staining of FoxP3 (c, e, g) and CD25 (d, f, h) in mucosal biopsy specimen from a healthy control (c, d), from a patient with untreated coeliac disease (e, f) and from a patient with increased intraepithelial lymphocytes count (g, h). The specimen from a healthy control shows few positive cells for both antibodies (c, d), whereas the specimen from a coeliac patient shows highly increased densities for both FoxP3 (e) and CD25 (f). Arrowheads indicate single positive cells in (b–d, h). DAB–haematoxylin stain, original magnification ×200.

Fig. 5.

The density of forkhead box P3 (FoxP3)- (a) and CD25 (b) -expressing cells in the lamina propria detected by immunohistochemistry. The median densities are shown by horizontal lines. The arrows indicate those patients with potential coeliac disease (potCD) who were diagnosed later with CD. The patients with CD, and type 1 diabetes (T1D) patients with CD, had a higher density of FoxP3-expressing cells than the patients with potCD, patients with T1D and potCD, T1D patients and controls (all P-values less or equal to 0·012, using the Mann–Whitney U-test). The patients with CD or with potCD with or without T1D had a higher density of CD25-expressing cells than the patients with T1D or the control patients (all P-values less or equal to 0·020, using the Mann–Whitney U-test). potCD: potential CD with elevated levels of T cell receptor γ/δ-expressing intraepithelial lymphocytes and/or presence of CD-associated antibodies; CONTR, control group with normal mucosa.

The proportion of CD25-expressing cells in the lamina propria was increased in paediatric patients with CD (P < 0·001, P < 0·001), in T1D patients with CD (P < 0·001, P < 0·001), in patients with potential CD (P = 0·020, P = 0·018) and in patients with T1D and potential CD (P = 0·008, P = 0·012) compared with groups of patients with T1D and normal mucosa and control patients (Fig. 5b).

The densities of cells expressing FoxP3 and CD25 in immunohistochemical stainings correlated with each other (r = 0·69, P < 0·001). Both the density of FoxP3-positive cells and CD25-positive cells in the lamina propria correlated with the quantity of mRNA for FoxP3 (r = 0·78, P < 0·001; r = 0·60, P = 0·001 respectively), for CD25 (r = 0·57, P < 0·001; r = 0·38, P = 0·016), for IFN-γ (r = 0·76, P < 0·001; r = 0·72, P < 0·001) and for IL-10 (r = 0·63, P < 0·001; r = 0·52, P = 0·005). The densities of FoxP3- and CD25-expressing cells correlated inversely with IL-18 mRNA expression (r = −0·53, P < 0·001; r = − 0·36, P = 0·016 respectively).

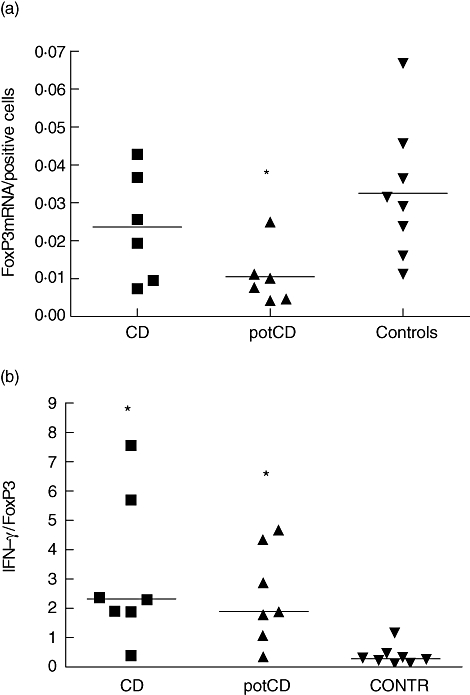

Activation of FoxP3 mRNA in relation to FoxP3-positive cells and IFN-γ mRNΑ

The ratio between FoxP3 mRNA and the number of FoxP3-positive cells was calculated for evaluation of the degree of activation of the FoxP3-positive cells (Fig. 6a). This ratio differed between the groups (P = 0·025), and was decreased in the patients with potential CD when compared with controls (P = 0·007). To evaluate the balance between effector T cell versus regulatory T cell activity we calculated the ratio between IFN-γ- and FoxP3-specific mRNA expression. The ratio of IFN-γ to FoxP3 mRNA in patients with CD was 2·33, in patients with potential CD 1·88 and in control patients 0·27 (P = 0·001 when patients with CD were compared with controls and P = 0·002 when subjects with potential CD were compared with controls) (Fig. 6b).

Fig. 6.

(a) The ratio between forkhead box P3 (FoxP3) mRNA and the number of FoxP3-positive cells. This ratio differed between the groups (P = 0·025), and was decreased in the patients with potential coeliac disease (potCD) when compared with controls (P = 0·007). (b) The ratio of interferon-γ and FoxP3-specific mRNAs. The horizontal lines show medians for each group. Patients with CD and the patients with potCD had a higher ratio than controls (P = 0·001 for CD and P = 0·002 for potCD). potCD: potential CD with elevated levels of T cell receptor γ/δ-expressing intraepithelial lymphocytes and/or presence of CD-associated antibodies; CONTR, control group with normal mucosa.

Discussion

We demonstrated the infiltration of FoxP3-expressing cells in the small intestinal biopsies of patients with active CD and potential CD. The subjects with only infiltrative, potential CD showed only minimal up-regulation of FoxP3-positive cells in the small intestine, which was not demonstrated as enhanced expression of FoxP3 mRNA. Thus, the up-regulation of FoxP3 transcripts in relation to the number of FoxP3-expressing cells seems to be impaired in the early stage of CD despite the remarkable inflammatory changes demonstrated as increased IFN-γ expression. No up-regulation of FoxP3 was seen in the intestinal inflammation associated with T1D.

Forkhead box P3 has been reported to be a marker of CD4+ CD25+ regulatory T cells and it is an essential transcription factor for the function of regulatory T cells [19,20]. Regulatory T cells can be divided into naturally occurring regulatory T cells which are induced against self-antigens expressed in the thymus, and into secondary regulatory T cells which are induced in the periphery [14,15]. Thymus-derived natural regulatory T cells express specifically FoxP3 transcription regulator, CD4, CD25 and CTLA-4 surface markers and produce both membrane-bound and secreted TGF-β. In humans, it has been shown that FoxP3-expressing CD4+ CD25+ regulatory T cells can be induced from peripheral CD4+ CD25– T cells upon stimulation [21,22]. Recent studies suggest that the induction of FoxP3 upon stimulation of human T cells is not always associated with the suppressor function of T cells [23,24]. These studies demonstrate that TCR-mediated stimulation results in the up-regulation of FoxP3 and those cells with up-regulated FoxP3 are hyporesponsive. Accordingly, the increased expression of FoxP3 is suggested to provide the means to regulate T cell activation negatively, which is mediated by repressing IL-2 and nuclear factor of activated T cells transcription. It seems that the generation of T cells with up-regulated FoxP3 expression is linked closely with immune activation, and represents an important mechanism to shut off the antigen-specific immune responses and inhibit the generation of uncontrolled immune activation that could lead to chronic inflammation.

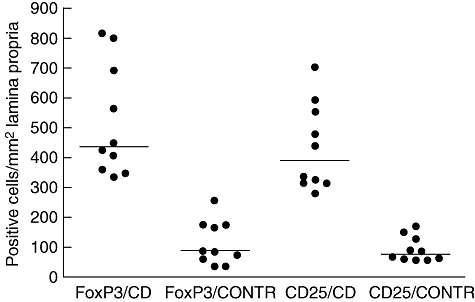

Increased expression of IFN-γ and CD25 was associated with both active and potential CD, which supports previous findings [5,7,18,25]. It has also been shown that gluten stimulation increases further the level of IFN-γ mRNA and the amount of CD25-positive T cells in in vitro studies [26,27]. Interestingly, in 1993 Halstensen and Brandtzaeg [25] had already shown that the numbers of CD25 expressing non-proliferating CD4+ cells were increased in the lamina propria of proximal jejunum in CD, suggesting that these cells function as regulatory T cells. In the paraffin-embedded biopsy samples we found a higher density of FoxP3-positive cells in lamina propria than the density of CD25-positive cells. As we had access to paraffin-embedded biopsy samples only from patients with T1D without CD, the immunohistochemical staining of biopsy samples from all study groups was performed in paraffin sections to make the comparison between the groups possible. The staining of CD25-positive cells in paraffin sections is not as sensitive a method as staining in frozen sections. For comparison, we studied frozen sections from an additional group of patients with CD and controls for the numbers of CD25- and FoxP3-expressing cells. These results are in agreement with the results performed in paraffin sections, indicating that increased numbers of CD25- and FoxP3-expressing cells in lamina propria are indeed present in CD. In frozen sections, the numbers of CD25- and FoxP3-expressing cells were at the same level because of the better sensitivity for staining of CD25 in frozen sections (for comparison, the results are shown in Fig. 7). Accordingly, we could show indirectly that most of FoxP3-expressing cells in the lesion of CD are CD25-expressing cells, as confirmed by double-staining protocol in frozen sections. We cannot exclude, however, the possibility that some of the FoxP3-expressing cells in lamina propria are indeed CD25-negative and do not function as regulatory T cells. On the other hand, cells other than FoxP3-positive regulatory T cells express CD25.

Fig. 7.

The density of forkhead box P3 (FoxP3)- and CD25-expressing cells in the lamina propria detected by immunohistochemistry in frozen sections. Horizontal lines represent median values of the groups. CD, coeliac disease; CONTR, control group with normal mucosa.

Despite the high numbers of FoxP3-expressing T cells in the mucosal lesion, these cells are not able to suppress the harmful immune response in active CD. Interestingly, the expression of TGF-β did not correlate with FoxP3 expression, which suggests an impaired expression of TGF-β by FoxP3-expressing cells. A decrease in membrane-bound TGF-β on regulatory T cells has been found to be associated with the destruction of beta-cells in an autoimmune model of diabetes [28]. Recently, CD4+ CD25+ FoxP3-expressing cells were cultured from colonic biopsies of patients with Crohn's disease [29]. The function of the regulatory T cells in Crohn's disease was not aberrant according to the tests performed and the authors speculated that the ratio of regulatory and effector T cells may, instead, be decreased in intestinal inflammation. The small size of the intestinal biopsy samples in our study did not make it possible to isolate enough immune cells for functional studies. To evaluate the balance between regulatory and effector activity we calculated the IFN-γ : FoxP3 ratio. The ratio was increased in potential CD, as well as in active CD, suggesting higher effector activity in relation to regulatory activity. It is of interest that the infiltration of FoxP3-positive cells was demonstrated in both acute and potential CD, but increased FoxP3 transcription was found only in acute CD. Thus, the FoxP3 transcription was proportionally low in potential CD, which suggests that impaired up-regulation of FoxP3-related suppressive mechanisms plays a role in the pathogenesis of CD.

In the early, infiltrative phase of CD, epithelial cells are probably destroyed by innate immune mechanisms, dependent upon the presence of toxic gliadin peptides. In patients with CD, gliadin peptides induce major histocompatibility complex class I-related chain (MICA) expression on epithelial cells and makes them susceptible to destruction by intraepithelial natural killer (NK) and T cells [2,30]. In this phase inflammation is limited to the intraepithelial space, and we found only a slight increase in the numbers of cells positive for FoxP3. The role of adaptive immunity to gliadin/tissue transglutaminases is more pronounced with the progression of the disease when massive secretion of inflammatory cytokines causes more severe epithelial cell destruction by several mechanisms. We saw a marked increase of both mRNA for FoxP3 and cells positive for it in the lamina propria only at the later stage of CD. Stock et al.[31] have reported that adaptive regulatory T cells expressing both FoxP3 and T-bet, a transcription factor for IFN-γ, were developed in vivo during a type 1 immune response. These cells secreted both IL-10 and IFN-γ. We found that the expression of both IFN-γ and IL-10 correlated with FoxP3 expression in small intestinal inflammation in CD, which suggests that a similar T helper 1-type regulatory T cell population might also be present in coeliac lesions. The increased expression of IL-10 has been reported in untreated CD patients and in gluten-challenged CD patients in the IEL of the small intestinal biopsies [32] and in whole duodenal biopsies from untreated CD patients [33]. IL-10-secreting T cell lines derived from CD mucosa have been shown to suppress the IFN-γ-secreting gliadin-specific intestinal T cells in vitro[34]. However, the presence of regulatory IL-10-secreting cells in CD mucosa does not inhibit the development of villus atrophy, nor are the mechanisms of suppression in potential CD explained by these findings.

We found that the number of FoxP3-expressing regulatory T cells in healthy small intestine was low. Interestingly, the ratio of FoxP3 mRNA to the number of FoxP3-positive cells was increased in controls when compared with potential CD. This could indicate that the maintenance of oral tolerance is not related to the expansion of the FoxP3-positive cell population but is related, rather, to the up-regulation of FoxP3 transcripts. The findings in acute CD suggest that up-regulation of FoxP3 in the human small intestine correlates with the degree of inflammation, and accordingly inflammation is the trigger of mucosal FoxP3 in humans. Despite the increase in the number of FoxP3-positive cells and FoxP3 transcripts in CD, inflammation and tissue destruction occurs. FoxP3 was not up-regulated in T1D despite the mild intestinal inflammation, which raises the question of whether this reflects a defect in the activation of regulatory mechanisms.

Another important finding in this study was the remarkably enhanced mRNA expression of IL-18 associated strongly with T1D. Increased expression of IL-18 was seen in T1D patients without any signs of CD, and was also seen in T1D patients with potential CD, but not in potential CD. The expression of IL-18 mRNA was even lower in patients with CD. Our finding of low IL-15 and IL-18 mRNA expression in CD mucosa is in agreement with earlier reports, indicating unchanged IL-15 or IL-18 transcripts despite the increased numbers of IL-15- or IL-18-positive cells in the small intestinum from patients with untreated CD [35–38]. Secretion of IL-15 and IL-18 is controlled at post-transcriptional level and expression at protein level does not correlate necessarily with IL-18 mRNA expression. However, in patients with T1D expression of IL-18 mRNA in the small intestinal mucosa was elevated. Interestingly, virus infections are able to up-regulate IL-18 mRNA transcription and further secretion of active IL-18 in macrophages [39]. Our earlier observation of the increased density of IL-1α-expressing cells in the small intestinal biopsies of patients with T1D [13] fits well with this finding, as IL-1α and IL-18 are produced by activated macrophages. In animal studies it has been shown that IL-18 mRNA is expressed in the pancreatic islets during the course of diabetic insulitis [40]. In humans it has been shown that the presence of T1D-associated autoantibodies, especially multiple autoantibodies, is associated with increased levels of circulating IL-18 [41]. Also the polymorphisms in the promoter of IL-18 gene have been suggested to be associated with the susceptibility of T1D [42]. The increased expression of IL-18 mRNA found in patients with T1D supports the abnormal activation of the gut immune system in the pathogenesis of T1D.

In this study we have shown that the intestinal inflammation in both acute and potential CD is characterizedby infiltration of FoxP3-positive cells, whereas decreased up-regulation of FoxP3 mRNA in relation to the number of FoxP3-positive cells is seen in potential CD. Together with the increased ratio of IFN-γ to FoxP3 demonstrated in CD, our observations suggest that deviation of regulatory mechanisms at the early stage of CD may contribute to the persistence of intestinal inflammation.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Mr Harry Lybeck and Ms Sirkku Kristiansen for excellent technical assistance. The study was supported by the Finnish Cultural Foundation, the Academy of Finland, the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation International and the Sigrid Juselius Foundation.

References

- 1.Holm K, Mäki M, Savilahti E, Lipsanen V, Laippala P, Koskimies S. Intraepithelial gamma delta T-cell-receptor lymphocytes and genetic susceptibility to coeliac disease. Lancet. 1992;339:1500–3. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)91262-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maiuri L, Ciacci C, Ricciardelli I, et al. Association between innate response to gliadin and activation of pathogenic T cells in coeliac disease. Lancet. 2003;362:30–7. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13803-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meresse B, Chen Z, Ciszewski C, et al. Coordinated induction by IL15 of a TCR-independent NKG2D signaling pathway converts CTL into lymphokine-activated killer cells in celiac disease. Immunity. 2004;21:357–66. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Koning F, Schuppan D, Cerf-Bensussan N, Sollid LM. Pathomechanisms in celiac disease. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2005;19:373–87. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2005.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kontakou M, Sturgess RP, Przemioslo RT, Limb GA, Nelufer JM, Ciclitira PJ. Detection of interferon gamma mRNA in the mucosa of patients with coeliac disease by in situ hybridisation. Gut. 1994;35:1037–41. doi: 10.1136/gut.35.8.1037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Przemioslo RT, Kontakou M, Nobili V, Ciclitira PJ. Raised pro-inflammatory cytokines interleukin 6 and tumour necrosis factor alpha in coeliac disease mucosa detected by immunohistochemistry. Gut. 1994;5:1398–403. doi: 10.1136/gut.35.10.1398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Holm K, Savilahti E, Koskimies S, Lipsanen V, Mäki M. Immunohistochemical changes in the jejunum in first degree relatives of patients with coeliac disease and the coeliac disease marker DQ genes. HLA class II antigen expression, interleukin-2 receptor positive cells and dividing crypt cells. Gut. 1994;35:55–60. doi: 10.1136/gut.35.1.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Green PH, Rostami K, Marsh M. Diagnosis of coeliac disease. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2005;19:389–400. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2005.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Holmes GK. Screening for coeliac disease in type 1 diabetes. Arch Dis Child. 2002;87:495–8. doi: 10.1136/adc.87.6.495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Klemetti P, Savilahti E, Ilonen J, Åkerblom HK, Vaarala O. T-cell reactivity to wheat gluten in patients with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Scand J Immunol. 1998;47:48–53. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3083.1998.00255.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.MacFarlane AJ, Burghardt KM, Kelly J, et al. A type 1 diabetes-related protein from wheat (Triticum aestivum). cDNA clone of a wheat storage globulin, Glb1, linked to islet damage. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:54–63. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210636200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Auricchio R, Paparo F, Maglio M, et al. In vitro-deranged intestinal immune response to gliadin in type 1 diabetes. Diabetes. 2004;53:1680–3. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.7.1680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Westerholm-Ormio M, Vaarala O, Pihkala P, Ilonen J, Savilahti E. Immunologic activity in the small intestinal mucosa of pediatric patients with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes. 2003;52:2287–95. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.9.2287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fontenot JD, Rudensky AY. A well adapted regulatory contrivance: regulatory T cell development and the forkhead family transcription factor Foxp3. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:331–7. doi: 10.1038/ni1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sakaguchi S. Naturally arising Foxp3-expressing CD25+CD4+ regulatory T cells in immunological tolerance to self and non-self. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:345–52. doi: 10.1038/ni1178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Revised Criteria for Diagnosis of Coeliac Disease. Report of the Working Group of European Society of Paediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition. Arch Dis Child. 1990;65:909–11. doi: 10.1136/adc.65.8.909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Savilahti E, Arato A, Verkasalo M. Intestinal gamma/delta receptor-bearing T lymphocytes in celiac disease and inflammatory bowel diseases in children. Constant increase in celiac disease. Pediatr Res. 1990;28:579–81. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199012000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Westerholm-Ormio M, Garioch J, Ketola I, Savilahti E. Inflammatory cytokines in small intestinal mucosa of patients with potential coeliac disease. Clin Exp Immunol. 2002;128:94–101. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2002.01798.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fontenot JD, Gavin MA, Rudensky AY. Foxp3 programs the development and function of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:330–6. doi: 10.1038/ni904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Khattri R, Cox T, Yasayko S-A, Ramsdell F. An essential role for Scurfin in CD4+CD25+ T regulatory cells. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:337–42. doi: 10.1038/ni909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Walker MR, Kasprowicz DJ, Gersuk VH, et al. Induction of FoxP3 and acquisition of T regulatory activity by stimulated human CD4+CD25– T cells. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:1437–43. doi: 10.1172/JCI19441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morgan ME, van Bilsen JH, Bakker AM, et al. Expression of FOXP3 mRNA is not confined to CD4+CD25+ T regulatory cells in humans. Hum Immunol. 2005;66:13–20. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2004.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gavin MA, Torgerson TR, Houston E, et al. Single-cell analysis of normal and FOXP3-mutant human T cells: FOXP3 expression without regulatory T cell development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:6659–64. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509484103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang J, Ioan-Facsinay A, van der Voort EI, Huizinga TW, Toes RE. Transient expression of FOXP3 in human activated nonregulatory CD4+ T cells. Eur J Immunol. 2007;37:129–38. doi: 10.1002/eji.200636435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Halstensen TS, Brandtzaeg P. Activated T lymphocytes in the celiac lesion: non-proliferative activation (CD25) of CD4+ alpha/beta cells in the lamina propria but proliferation (Ki-67) of alpha/beta and gamma/delta cells in the epithelium. Eur J Immunol. 1993;23:505–10. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830230231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nilsen EM, Jahnsen FL, Lundin KE, et al. Gluten induces an intestinal cytokine response strongly dominated by interferon gamma in patients with celiac disease. Gastroenterology. 1998;115:551–63. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70134-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Halstensen TS, Scott H, Fausa O, Brandtzaeg P. Gluten stimulation of coeliac mucosa in vitro induces activation (CD25) of lamina propria CD4+ T cells and macrophages but no crypt-cell hyperplasia. Scand J Immunol. 1993;38:581–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.1993.tb03245.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gregg RK, Jain R, Schoenleber SJ, et al. A sudden decline in active membrane-bound TGF-β impairs both T regulatory cell function and protection against autoimmune diabetes. J Immunol. 2004;173:7308–16. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.12.7308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kelsen J, Agnholt J, Hoffmann HJ, Romer JL, Hvas CL, Dahlerup JF. Foxp3+CD4+CD25+ T cells with regulatory properties can be cultured from colonic mucosa of patients with Crohn's disease. Clin Exp Immunol. 2005;141:549–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2005.02876.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hue S, Mention JJ, Monteiro RC, et al. A direct role for NKG2D/MICA interaction in villous atrophy during celiac disease. Immunity. 2004;21:367–77. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stock P, Akbari O, Berry G, Freeman GJ, Dekruyff RH, Umetsu DT. Induction of T helper type 1-like regulatory cells that express Foxp3 and protect against airway hyper-reactivity. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:1149–56. doi: 10.1038/ni1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Forsberg G, Hernell O, Melgar S, Israelsson A, Hammarström S, Hammarström ML. Paradoxical coexpression of proinflammatory and down-regulatory cytokines in intestinal T cells in childhood celiac disease. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:667–78. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.35355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Salvati VM, Mazzarella G, Gianfrani C, et al. Recombinant human interleukin 10 suppresses gliadin dependent T cell activation in ex vivo cultured coeliac intestinal mucosa. Gut. 2005;54:46–53. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.023150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gianfrani C, Levings MK, Sartirana C, et al. Gliadin-specific type 1 regulatory T cells from the intestinal mucosa of treated celiac patients inhibit pathogenic T cells. J Immunol. 2006;177:4178–86. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.6.4178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Maiuri L, Ciacci C, Auricchio S, Brown V, Quaratino S, Londei M. Interleukin 15 mediates epithelial changes in celiac disease. Gastroenterology. 2000;119:996–1006. doi: 10.1053/gast.2000.18149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Salvati VM, MacDonald TT, Bajaj-Elliott M, et al. Interleukin 18 and associated markers of T helper cell type 1 activity in coeliac disease. Gut. 2002;50:186–90. doi: 10.1136/gut.50.2.186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mention JJ, Ben Ahmed M, Bègue B, et al. Interleukin 15: a key to disrupted intraepithelial lymphocyte homeostasis and lymphomagenesis in celiac disease. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:730–45. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(03)01047-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.León AJ, Garrote JA, Blanco-Quirós A, et al. Interleukin 18 maintains a long-standing inflammation in coeliac disease patients. Clin Exp Immunol. 2006;146:479–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2006.03239.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pirhonen J, Sareneva T, Julkunen I, Matikainen S. Virus infection induces proteolytic processing of IL-18 in human macrophages via caspase-1 and caspase-3 activation. Eur J Immunol. 2001;31:726–33. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200103)31:3<726::aid-immu726>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hong TP, Andersen NA, Nielsen K, et al. Interleukin-18 mRNA, but not interleukin-18 receptor mRNA, is constitutively expressed in islet beta-cells and up-regulated by interferon-gamma. Eur Cytokine Netw. 2000;11:193–205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nicoletti F, Conget I, Di Marco R, et al. Serum levels of the interferon-gamma-inducing cytokine interleukin-18 are increased in individuals at high risk of developing type I diabetes. Diabetologia. 2001;44:309–11. doi: 10.1007/s001250051619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kretowski A, Mironczuk K, Karpinska A, et al. Interleukin-18 promoter polymorphisms in type 1 diabetes. Diabetes. 2002;51:3347–9. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.11.3347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]