Abstract

This review summarizes results of our recent solid-state NMR investigations on polyunsaturated 18:0–22:6n3-PC/PE/PS and 18:0–22:5n6-PC bilayers. Data on structure and dynamics of the polyunsaturated docosahexaenoyl (DHAn3, 22:6n3) and docosapentaenoyl chains (DPAn6, 22:5n6), investigated at physiological conditions, are reported. Lipid-protein interaction was studied on reconstituted bilayers containing the G-protein coupled membrane receptor rhodopsin as well as on rod outer segment disk membranes prepared from bovine retinas. Results reveal surprisingly rapid conformational transitions of polyunsaturated chains and existence of weakly-specific interactions of DHAn3 with spatially distinct sites on rhodopsin.

Keywords: Docosahexaenoic acid, docosapentaenoic acid, phosphatidylcholine, phosphatidylethanolamine, phosphatidylserine, G-protein coupled membrane receptor, rhodopsin, nuclear magnetic resonance

Introduction

The importance of highly unsaturated fatty acids (HUFA) in health and for the development of mammalian brain was convincingly demonstrated (Salem et al., 2001). The mechanisms by which polyunsaturated lipid species may influence biological function at the molecular level are now attracting considerable attention. Many neuronal G-protein coupled membrane receptors (GPCR) are located in membranes containing very high concentrations of docosahexaenoic acid (DHAn3, 22:6n3) a fatty acid with 22 carbon atoms and six double bonds evenly spread over the length of the hydrocarbon chain. It has been known since the 1970ies that membranes with high concentration of HUFA have different biophysical properties. But only recently have experiments gained sufficient resolution to fully investigate the unique conformational properties of polyunsaturated fatty acids in lipid bilayers.

Two mechanism of HUFA action on proteins must be considered: on one hand, HUFA may influence function by altering biophysical properties of the lipid matrix. Such action most likely occurs in neural membranes with high HUFA content like synaptosomes and the retina. But even in membranes with lower HUFA content biophysical properties could be important as long as HUFA accumulate near membrane proteins. On the other hand, HUFA and their derivatives may act as weakly- or strongly binding ligands that interact directly with membrane proteins.

Until recently the majority of researchers ascribed the special role of polyunsaturated hydrocarbon chains to rigidity and a preference for particular conformations. Indeed, the most prominent polyunsaturated fatty acid, DHAn3, has fewer degrees of freedom due to its six cis-locked double bonds than comparable saturated hydrocarbon chains. Inspired by the conformation of DHAn3 found in fatty acid crystals and by molecular simulations, this led to the proposition that long-lived DHAn3 conformers such as angle-iron or helical may exist in fluid bilayers (Applegate and Glomset, 1986). It was suggested that such conformers could promote packing of lipids in tight, regular arrays in the bilayer or that lipid packing of other hydrocarbon chains is perturbed by the peculiar structure of DHAn3. However, our experiments indicate that DHAn3 is highly flexible, converting rapidly between conformations on the sub-nanosecond time scale. The flexibility and adaptability of polyunsaturated fatty acids like DHAn3 imparts unique elastic properties on lipid bilayers. It is conceivable that this may ease conformational transitions of GPCR upon activation. Furthermore, the flexibility of DHAn3 in combination with its ability to engage in polar interactions may allow for tighter interaction with α-helical proteins and even entry into the core of GPCR (Feller et al., 2003).

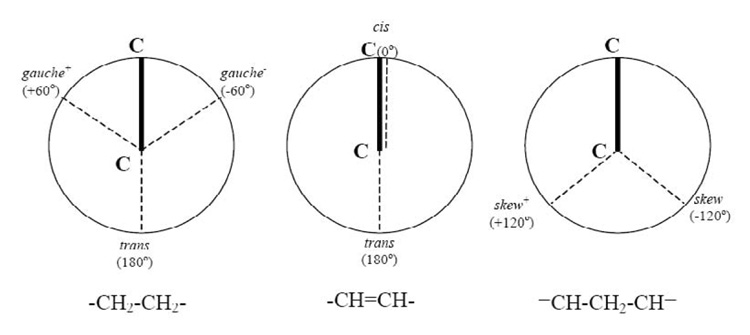

Properties of polyunsaturated acyl chains

Polyunsaturated fatty acids contain the repeating 1,4-pentadiene structural motif - two or more double bonds per chain separated by methylene groups (–CH=CH-CH2-CH=CH-). Chain conformations are characterized by dihedral bond angles, gauche+, gauche−, or trans, for saturated hydrocarbon chains, cis or trans for double bonds (biosynthesis results almost exclusively in the cis-configuration), and skew+ or skew− for the C-C bonds of methylene groups sandwiched between double bonds.

In fluid bilayers dihedral bond angles change rapidly and other than optimal bond angles may occur. Conformational freedom is reflected in order parameters of chemical bonds and in correlation times of bond motions. The measurement of assigned order parameters of DHAn3 was achieved by a combination of 2H NMR order parameter measurements on lipids with perdeuterated docosahexaenoic acid chains, by 13C magic-angle spinning (MAS) NMR with 1H-13C cross-polarization (CP) to measure the strength of 1H-13C dipole-dipole interactions, and indirectly by measurement of longitudinal and transverse 13C NMR relaxation times at two levels of magnetic field strength.

Chain order of 18:0–22:6n3-PC

We expressed perdeuterated DHAn3 by growing the dinoflagellate Crypthecodinium cohnii in partially deuterated media. When grown in 50% D2O, DHAn3 is deuterated at random to 38 %, except for the terminal methyl group that is deuterated to 30%. The DHAn3 containing triglycerides were extracted and fatty acids converted to methyl esters. After fractional distillation and preparative HPLC separation, the deuterated DHAn3 had a purity of better than 98% as demonstrated by NMR and gas chromatography. A batch of 15 grams of pure, perdeuterated DHAn3 was produced in collaboration with Martek Biosciences Corporation (Columbia, MD). Mixed chain 18:0–22:6(d31)-PC, 18:0–22:6(d31)-PE, and 18:0–22:6(d31)-PS were synthesized by Avanti Polar Lipids (PC - phosphatidylcholine; PE - phosphatidylethanolamine; PS - phosphatidylserine).

The 2H NMR experiments were conducted with proton decoupling to suppress 1H-2H dipolar interactions in the randomly deuterated chain. This yielded well resolved quadrupolar splittings which allowed precise determination of order parameters. A limited assignment was achieved by taking advantage of differences in 2H chemical shifts between resonances. Those differences were made more prominent in the appearance of 2H NMR spectra by conducting off-magic angle spinning experiments that reduce quadrupolar splittings. Finally, assignment of all order parameters was achieved by comparison with results of 1H-13C CP-MAS NMR experiments conducted on 18:0–22:6n3-PC with protonated DHAn3.

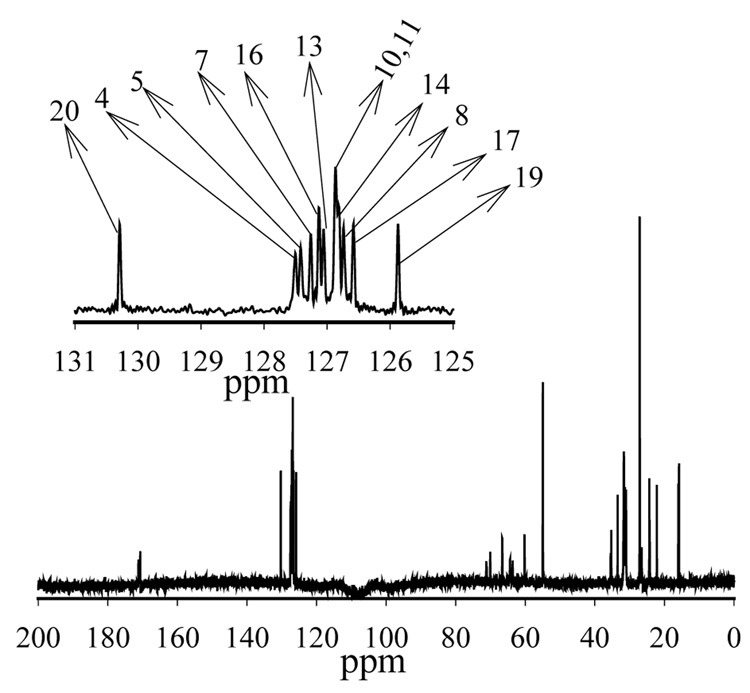

The much wider range of 13C NMR chemical shifts in combination with exceptional resolution of 13C resonances afforded by magnetic susceptibility-matched receiver coils and MAS rotor inserts for 11 µL spherical samples (Bruker Biospin Corp., Billerica, MA) permitted resolving resonances of almost all of the 22 carbons of DHAn3. Resonances were assigned by two-dimensional 13C-13C MAS Correlated spectroscopy (13C-13C COSY) on 13C-labeled DHAn3 that was added as fatty acid at low concentration to POPC bilayers, by comparison with assigned chemical shifts of polyunsaturated fatty acids in organic solvent (Gunstone, 1990), and by peculiarities in spin-lattice relaxation behavior of carbons along the DHAn3 chain predicted by molecular simulations (Feller et al., 2002). The 13C labeled DHAn3 was expressed by growing Crypthecodinium cohnii with 13C-labeled glucose (Martek Biosciences Corporation, Columbia MD).

At first we attempted to measure 1H-13C bond order parameters by a two-dimensional 13C MAS NMR experiment, Dipolar Recoupling On axis with Scaling and Shape preservation, DROSS (Gross et al., 1997), an experiment that recouples 1H-13C spin dipolar interactions in the f1 spectral domain while maintaining the excellent 13C chemical shift resolution in the f2 –domain (Gawrisch et al., 2002). The results revealed that the two protons at carbon C2 have different order parameters (chemical non-equivalence). However, most of the other dipolar interactions were too small to be resolved in the f1 spectral domain. Their values were determined by 1H-13C CP-MAS NMR experiments conducted as a function of contact time. By fitting the contact time dependence of 13C resonance intensity we obtained the time constant of 1H-13C magnetization transfer, TCH, which is proportional to the strength of 1H-13C spin-dipole interaction. In good approximation, spin-dipolar interactions have the same angular dependence on the orientation of the magnetic field as 2H quadrupolar interactions of 2H-C bonds. In other words, 1H-13C dipolar interactions yield the same bond order parameter as 2H quadrupolar interactions. The only difference is that 1H-13C dipolar interactions are somewhat weaker than 2H quadrupolar interactions, shifting the time base of rapid averaging from ~10−5 s for 2H NMR to ~10−4 s for 13C NMR. If lipid movements have spectral density within this range, then 13C order parameters could be lower. Since this is the range of correlation times of collective lipid motions, all 13C NMR order parameters of the DHAn3 chain are reduced by the same factor if such motions occur. The proportionality factor between TCH (1H-13C dipolar interaction) and 2H NMR order parameters was determined by comparison with assigned 2H NMR order parameters of DHAn3 vinyl, methylene, and methyl groups, therefore correcting results to the time base of 2H NMR (Eldho et al., 2003).

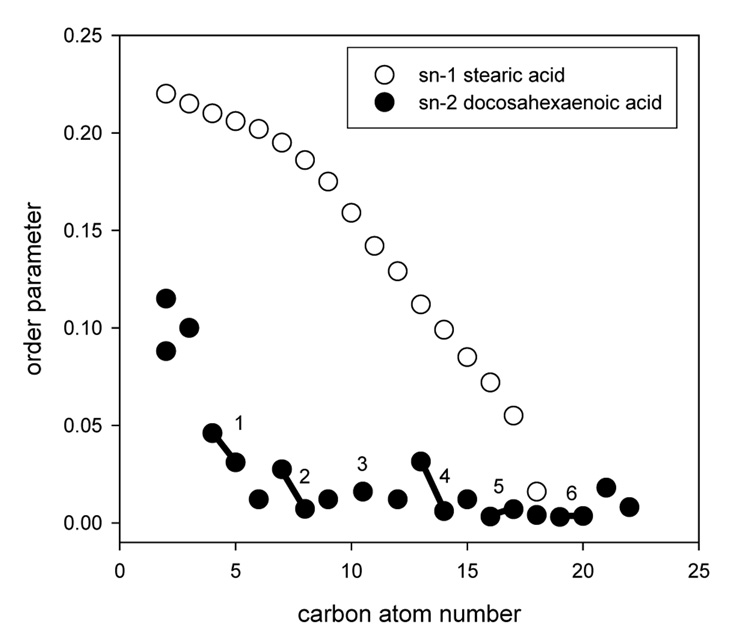

Finally, the order parameters of the saturated stearic acid chain at position sn-1 were determined by 2H NMR (Holte et al., 1995). The experimentally assigned order parameter profiles of both hydrocarbon chains in 18:0–22:6n3-PC are shown in Fig. 4. The saturated sn-1 chain has an order parameter plateau stretching from the carbonyl group to carbon atom C9. Order declines rapidly from C10 to C22, which is typical for saturated hydrocarbon chains in biomembranes. The much lower order parameters of the DHAn3 chain at C2 and C3 as well as the chemical non-equivalence of the two protons at C2 are consistent with a parallel orientation of this chain segment to the bilayer surface. The lower order in double bonds is mostly the result of double bond geometry: double bonds oriented parallel to the bilayer normal have their protons oriented at the “magic angle” (54.7°) for which order parameters are zero, even in the absence of motions. However, the very low order of methylene protons between double bonds may only result from fairly unrestricted chain motions. Remarkably, all methylene protons sandwiched between double bonds in DHAn3 (C6, C9, C12, C15) have the same very low order parameter, S=0.012. The order of the last methylene group between double bonds, C18, is even lower (S=0.004) reflecting a qualitative difference in the freedom of motions of the segment from the last double bond to the terminal methyl group.

Fig. 4.

Order parameter profiles of stearic acid (18:0) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHAn3, 22:6n3) in 18:0–22:6n3-PC. The carbons linked by the six double bonds of DHAn3 are indicated by bars and numbers. Experimental errors are on the order of symbol size or less.

Polyunsaturated DHAn3 vs. DPAn6

The first reports concerning biological implications of DHAn3 to DPAn6 replacement in brain were published already in the 1960ies (Mohrhauer and Holman, 1963). However, biophysical studies obtained on lipids with fewer double bonds per hydrocarbon chain than DHAn3 and DPAn6 suggested that changes in membrane properties caused by the deletion of a single double bond close to the methyl end where chain order is lowest would be too small to be functionally significant. This was frequently cited as evidence that changes in membrane properties from DHAn3 to DPAn6 replacement are unlikely to explain biological effects of n-3 fatty acid deficiency. Until recently it was not possible to prove predictions because of a lack of sufficient quantities of purified DPAn6 and because of insufficient resolution of experimental methods.

A mixture of triacylglycerols rich in DHAn3 and DPAn6, extracted from a culture of the algae-like microorganism Schizochytrium sp. was kindly provided by OmegaTech (Boulder, CO). The polyunsaturated fatty acids were extracted and purified by NuCheck Prep (Elysian, MN) by urea crystallization. Purification of DPAn6 proved challenging because it is just a byproduct of DHAn3 expression with a small structural difference to DHAn3. Separation of DPAn6 was achieved by preparative HPLC using an inverse column. DPAn6-enriched fractions were re-injected five times to reach a purity of 98% as determined by 1H- and 13C high-resolution NMR and gas chromatography. Six grams of DPAn6 were produced and utilized for synthesis of mixed-chain 18:0–22:5n6-PC/PE/PS (Avanti Polar Lipids, Alabaster, AL).

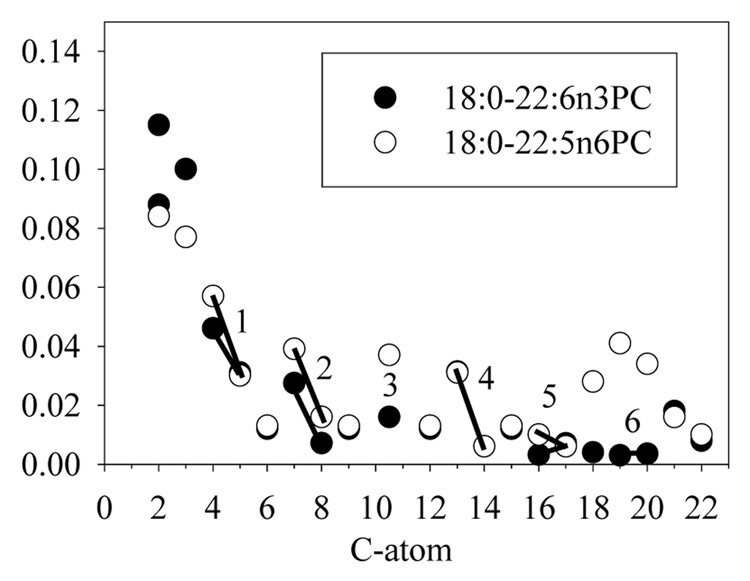

The chain order parameters of DPAn6 in 18:0–22:5n6-PC were measured by 1H-13C CP-MAS NMR as described above. Results are presented in Fig. 5. Order parameters of carbons in double bonds 1–4 of both DHAn3 and DPAn6 are higher at the first carbon of each bond. This repeating pattern points to a similar structural preference in the upper section of both hydrocarbon chains. However, all order parameters are low, consistent with rapid chain isomerization. There is a tendency for slightly higher order in the olefin range of DPAn6. The order parameters of chain segments C18–21 of DPAn6 are higher due to the lack of double bond number six in DPAn6.

Fig. 5.

The order parameter profiles of DHAn3 and DPAn6 chains in 18:0(d35)–22:6n3-PC (●)and 18:0(d35)-22:5n6- PC (○) respectively (Eldho et al., 2003). Order parameters were determined from measurements of cross-polarization rates, calibrated to 2H NMR order parameters of 18:0–22:6n3(d31)-PC with a deuterated DHAn3 chain. The double bonds are highlighted with bars and labeled with numbers.

Chain dynamics

Chain dynamics were studied by two-dimensional 1H MAS Nuclear Overhauser Enhancement Spectroscopy (1H MAS NOESY) (Feller et al., 1999; Huster et al., 1999; Huster and Gawrisch, 1999) and 13C MAS NMR longitudinal (T1) and transverse (T2) relaxation time measurements (Eldho et al., 2003; Feller et al., 2002; Soubias and Gawrisch, 2007). Relaxation times depend on amplitudes and correlation times of molecular motions covering the range from pico- to microseconds. The theory that links NMR relaxation to molecular motions is well established (see e.g. (Brown et al., 1995; Gawrisch, 2005)).

Cross-relaxation in fluid lipid matrices is dominated by intermolecular 1H-1H interactions. The distance between protons in fluid bilayers varies rapidly with time. Also, location of molecular segments varies such that even distant segments like ends of hydrocarbon chains and headgroups get close to each other, albeit with low probability (Huster and Gawrisch, 1999). This disorder in fluid bilayers is reflected in the cross-relaxation rates. Their values primarily reflect probability of interaction between lipid segments (Feller et al., 1999; Huster et al., 1999).

Cross-relaxation in 18:0–22:6n3-PC/PE/PS and 18:0–22:5n6-PC bilayers (Eldho et al., 2003; Huster et al., 1998) point at tumultuous disorder of polyunsaturated chain location and movements. All segments of polyunsaturated chains have low but finite probability to interact with the lipid/water interface. Also, the spin-lattice relaxation times of DHAn3 protons point at very rapid chain movements.

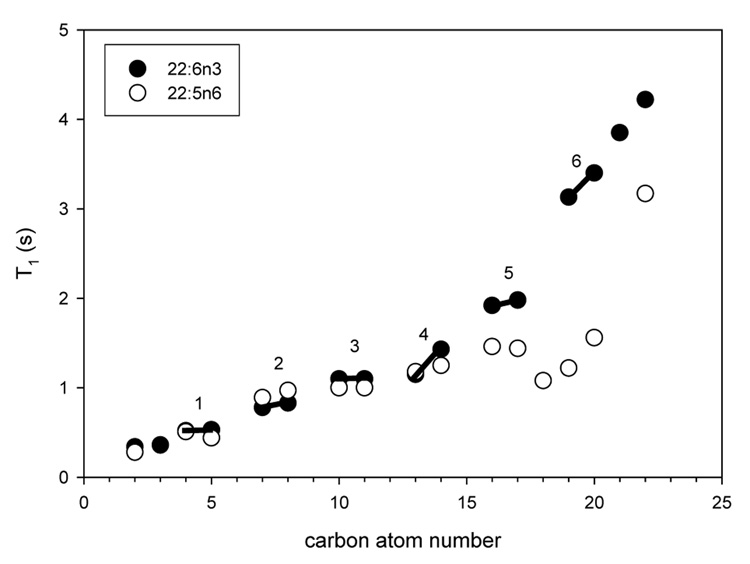

Detailed information on chain dynamics with resolution for all carbon atoms is obtained by 13C-MAS NMR relaxation analysis. The T1 relaxation times increase in a step-wise fashion from double bond to double bond moving down the chain towards the bilayer center. This behavior points at high isomerization rates of dihedral angles between double bonds. Also, relaxation times of DHAn3 carbon atoms C16–C22 are much longer than for DPAn6, consistent with molecular motions of larger amplitude and shorter motional correlation times in DHAn3. The lack of a magnetic field dependence of T1 (Soubias and Gawrisch, 2007) indicates that DHAn3 isomerization is entirely dominated by motions with correlation times on the sub-nanosecond timescale. Using a Lipari-Szabo-type relaxation analysis (Lipari and Szabo, 1982), corresponding to the isotropic limit of the anisotropic diffusion model of lipids in bilayers by Brown (Brown, 1982), we extracted the typical correlation time of rapid bond motions and the chain order parameter profile of DHAn3 (Soubias and Gawrisch, 2007).

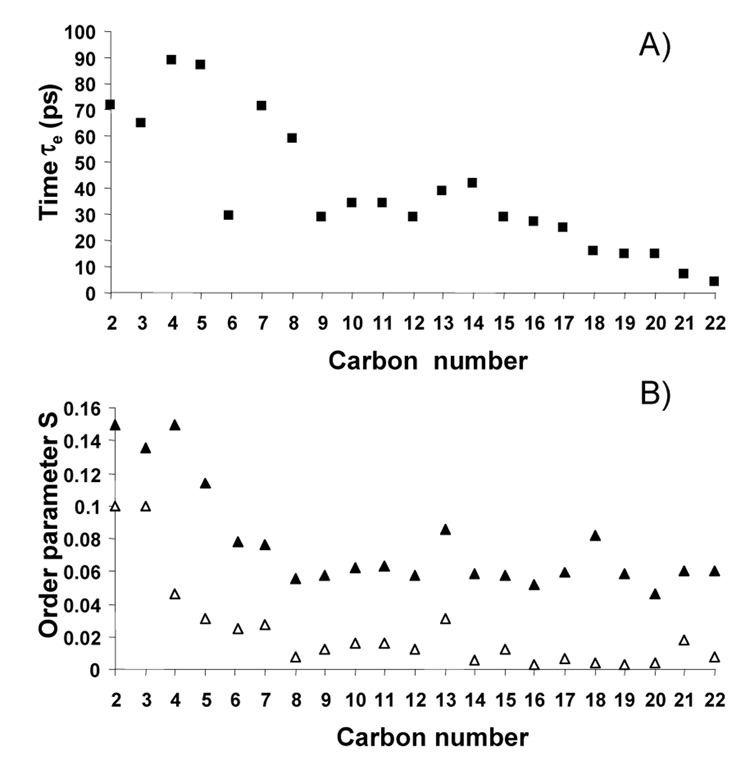

DHAn3 chains isomerize with correlation times on the order of 80 ps for carbons near the carbonyl group to a few picoseconds near the methyl terminal end. By including the measured transverse relaxation times into the analysis, a solely relaxation-derived order parameter profile of DHAn3 was calculated as shown in Fig. 7. The time-base for which those order parameters are defined is very short, just 50 ns. Remarkably, those relaxation derived order parameters differ from the 2H NMR order parameter profile (time base 10−5 s) by just a constant factor, with some deviation for carbons C2 and C3 closest to the carbonyl group. This convincingly demonstrates that the DHAn3 chain explores its entire conformational space within 50 ns, except for the very top of the chain. The additional lowering of order stems solely from collective modes of lipid motion on the timescale from nano- to microseconds. In difference to DHAn3, longitudinal relaxation times, T1, of hydrocarbon chains in saturated lipids have a significant field dependence (Brown et al., 1983; Klauda et al., 2007), indicating that chain isomerization in saturated lipids has contributions to spectral density from motions with significantly longer correlation times than for DHAn3. This is remarkable, since until recently polyunsaturated chains like DHAn3 were considered to be less flexible.

Fig. 7.

(A) Correlation times of fast lipid motions measured by 13C NMR spin-lattice relaxation, and (B) C-H bond order parameters measured by spin-spin/spin-lattice 13C NMR relaxation analysis (filled triangles) and 2H NMR (open triangles) (Soubias and Gawrisch, 2007).

Interpretation of experimental results of DHAn3 motion benefited greatly from comparison with molecular simulations of 18:0–22:6n3-PC and 18:0–22:5n6-PC bilayers conducted by Scott Feller and Alex MacKerell (Feller et al., 2002). After the recent adjustment of chain potential functions in CHARMM, molecular dynamics simulations are now sufficiently accurate for calculation of realistic time-correlation functions of DHAn3 molecular motions. The Fourier transform of correlation functions yields spectral density distribution functions of 1H-13C dipolar interactions responsible for 13C NMR relaxation. This enabled an unprecedented quantitative comparison of relaxation behavior between molecular simulations and experiments.

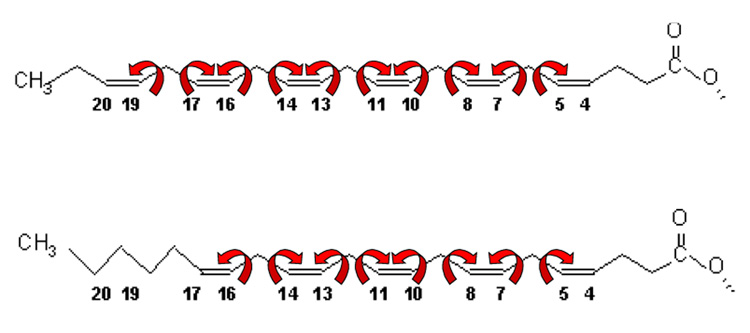

The critical degree of freedom describing the polyunsaturated acyl chain is the torsion angle for rotation about C-C single bonds connecting methylene and vinyl groups. Quantum chemical calculations revealed the cause of those high isomerization rates (Feller et al., 2002; Rabinovich and Ripatti, 1991). While the C-C bonds of saturated chains have lowest energy in trans(180°)/gauche+(60°)/gauche−(−60°) conformations, the two dihedral bond angles sandwiched between double bonds (=CH-CH2-CH=) prefer skew+(120°)/skew−(−120°) (see Fig. 2). Transitions between trans/gauche+/gauche− require passing energy barriers of ≈ 3 kcal/mol, which is 6-fold higher than a unit of thermal energy (kT ≈ 0.6 kcal/mol) at ambient temperature. In contrast, the energy barrier between skew+/skew− is only 0.8 kcal/mole, permitting very rapid isomerization of DHAn3 and DPAn6 (Feller et al., 2002).

Fig. 2.

Dihedral bond angles corresponding to conformations of energy minima in saturated and polyunsaturated chains.

It can be concluded that polyunsaturated chains themselves are exceptionally flexible with rapid structural transitions between large numbers of conformations, leading to the overall disordering of the membrane that is observed experimentally. The significant difference in chain dynamics between DHAn3 and DPAn6 at the methyl terminal end is related to the distribution of flexible bonds over polyunsaturated chains. The DPAn6 is a n-6 fatty acids with a stretch of four methylene segments near the terminal methyl group. In contrast, DHAn3 belongs to the family of n-3 fatty acids with a cis-locked double bond and a single methylene group at this location. The C-C bonds between methylene segments near the methyl terminal end of DPAn6 have much higher potential barriers for chain isomerization compared to C-C bonds linking the last double bond of DHAn3. This not only reduces chain dynamics of DPAn6 at the terminal methyl end, but also in the middle of the chain.

Distribution function of saturated and polyunsaturated chains in lipid bilayers

Remarkably, we observed not only differences in motional correlation times between DHAn3- and DPAn6- containing lipids but also a significant difference in density of polyunsaturated and saturated hydrocarbon chains in the direction along the bilayer normal. Initial indications that DHAn3 and DPAn6 chain distribution differs came from 2H NMR order parameter experiments conducted on the perdeuterated sn-1 chains of 18:0(d35)-22:6n3-PC and 18:0(d35)-22:5n6-PC. Order parameters near the terminal methyl end of 18:0(d35)-22:6n3-PC are much lower than for 18:0(d35)-22:5n6-PC (Eldho et al., 2003). A direct measure of chain density distributions was obtained by X-ray and neutron diffraction experiments conducted in collaboration with Stephanie Tristram-Nagle and Mihaela Mihailescu (Eldho et al., 2003; Mihailescu and Gawrisch, 2006).

Oriented membrane samples were prepared in an oxygen-free atmosphere to inhibit lipid oxidation during experiments lasting up to 36 hours. Lipids with butylated hydroxytoluene (BHT) added at a lipid/BHT molar ratio of 200/1 were stored in sealed, argon-filled ampoules in an ultracold freezer. For preparation of oriented bilayers, lipids were transferred to a glove box filled with pure nitrogen gas, and more BHT was added to raise the lipid/BHT molar ratio to 100/1. Samples on glass slides were prepared from organic solvent by evaporation. Experiments were conducted in an inert-gas atmosphere. Lipid integrity during experiments was confirmed by constancy of bilayer repeat spacings, as well as by gas chromatography and high resolution 1H NMR on selected samples after the measurements. Preparation procedures of oriented samples were optimized by measurement of mosaic spread of the spatially anisotropic 2H- and 31P lipid resonances by solid-state NMR. The X-ray experiments were conducted at the D1 line at CHESS (Cornell High Energy Synchrotron Source) and at the Advanced Neutron Diffractometer/Reflectometer (ANDR) that was recently installed at the NIST Center for Neutron Research, Gaithersburg, MD (http://www.ncnr.nist.gov/programs/reflect/ANDR).

Relative electron density profiles of fully hydrated 18:0–22:6n3-PC and 18:0–22:5n6-PC bilayers were obtained by Fourier reconstruction using the form factors from X-ray experiments, following protocols for investigation of fully hydrated, oriented lipid bilayers developed at the Nagle laboratory (Lyatskaya et al., 2001). The neutron diffraction experiments were conducted on 18:0–22:6n3-PC deuterated selectively in either the saturated stearic acid (18:0) chain or the polyunsaturated DHAn3 chain, or protonated in both chains. Experiments were conducted at 66% or 86 % relative humidity. According to 1H-, 2H, and 31P NMR experiments, the well-oriented samples were in the liquid crystalline lamellar phase and contained 6.1 or 9.4 water molecules per lipid, respectively (Binder and Gawrisch, 2001). Diffraction peaks were phased by systematic H2O-D2O exchange. Fourier synthesis of the coherent diffraction signal in reciprocal space using procedures developed at the laboratories of Stephen White (Wiener et al., 1991) and David Worcester (Worcester and Franks, 1976) yielded scattering length density (SLD) profiles of saturated 18:0 and polyunsaturated DHAn3 chains as well as the water distribution (Fig. 9).

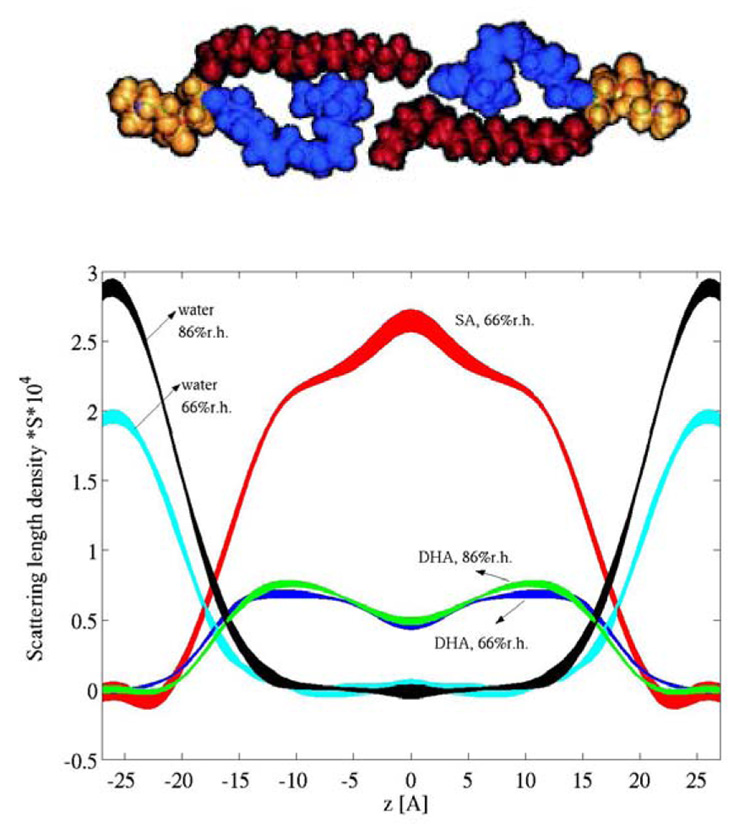

Fig. 9.

Scattering length density (SLD) distributions of lipid hydrocarbon chains and water calculated as density difference of bilayers with protonated and deuterated hydrocarbon chains (Mihailescu and Gawrisch, 2006). The line width reflects the uncertainty bands. The SLDs reflect higher densities of DHAn3 (blue) near the lipid water interface and of SA (red) in the bilayer center as shown in the model above the graph.

The broad trough seen in SLD of the DHAn3 chain is mostly the result of lower DHAn3 chain density in the bilayer center. This was confirmed by calculations using a realistic DHAn3 chain density distribution function from MD simulations (Eldho et al., 2003). Another surprising feature has been the SLD maximum of the saturated stearic acid (SA) chain density in the bilayer center. Other bilayers do not have such a SLD maximum but a trough which was explained by the larger volume of terminal CH3 groups compared to CH2. Therefore, the SLD maximum of SA in 18:0–22:6n3-PC bilayers reflects higher SA chain density in the bilayer center. Obviously, the SA chains fill the voids that are left by lower DHAn3 chain density in this region. Dynamic interdigitation of SA chains from the two opposing monolayers in a bilayer may contribute to higher SA density as well.

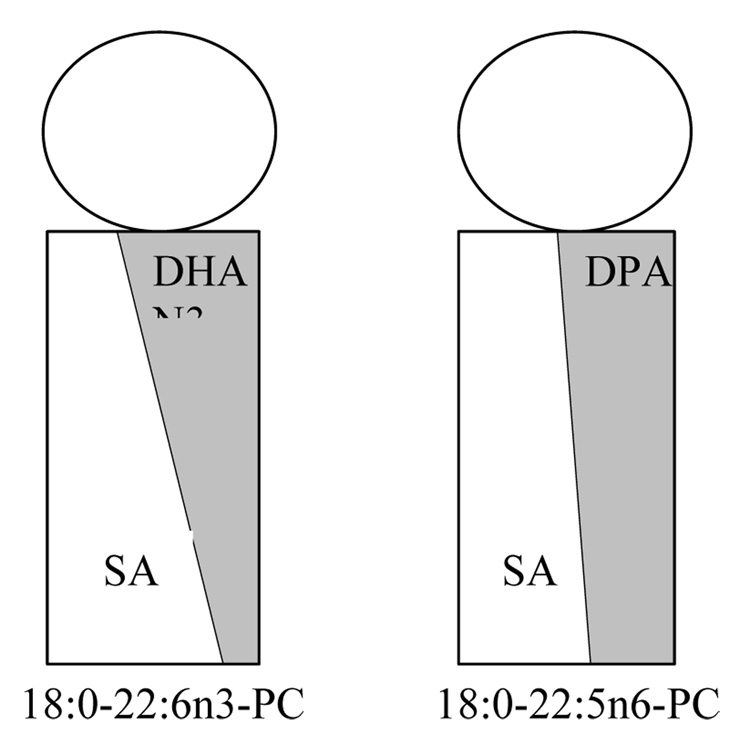

Similar information about distribution of chain densities was obtained at full hydration by X-ray diffraction studies. Both polyunsaturated chains have a significantly larger electron density than the stearic acid chain. This enabled us to extract information about differences in DHAn3 and DPAn6 chain density distribution between 18:0–22:6n3-PC and 18:0–22:5n6-PC from electron density profiles of both membranes. The bilayer thickness and area per lipid molecule were identical for DHAn3 and DPAn6 containing bilayers, but the width of the so-called methyl trough was significantly larger for 18:0–22:6n3-PC. The lower electron density seen out to 12 Å from the center of 18:0–22:6n3-PC bilayers points at an increased concentration of the stearic acid chain near the bilayer center.

With the loss of a single double bond at the methyl terminal end of the polyunsaturated chain (DHAn3 to DPAn6 replacement) a significant redistribution of chain densities takes place. The densities of stearic acid and DPAn6 chains tend to equalize at the interface and the bilayer center which restricts movements of the methyl terminal end of stearic acid in 18:0(d35)-22:5n6-PC compared to 18:0(d35)-22:6n3-PC. This explains why order parameters of stearic acid in 18:0(d35)-22:5n6-PC are somewhat higher at the lower half of the chain.

Lateral membrane organization in HUFA lipid mixtures

Studies of inhomogeneous lipid distribution in mixed lipid membranes have a long history. Lipid domain formation triggered by differences in interaction energies between lipid species is a well-known phenomenon. It has been studied for decades in the gel-fluid phase transition region of lipid bilayers. Much less is known about formation of domains and clusters in the biologically more relevant liquid-crystalline phase, although such phenomena are widely discussed. The hypothesis that cholesterol triggers formation of so-called rafts received a lot of attention. Fatty acid unsaturation may play an important role in the formation of domains since it is known that cholesterol prefers interaction with saturated lipids (Nakagawa et al., 1979; Rujanavech and Silbert, 1986; Smaby et al., 1997). More recently Stephen Wassall’s laboratory studied interaction of cholesterol with polyunsaturated lipid species (Shaikh et al., 2006; Shaikh et al., 2004). Here our results on lateral organization in mixed bilayers composed of 18:0–22:6n3-PC/PE/PS/cholesterol are summarized.

We had shown earlier that 1H MAS NOESY cross-relaxation in fluid bilayers is dominated by intermolecular interaction between lipid protons (Huster et al., 1999; Yau and Gawrisch, 2000). The method does not require introduction of potentially perturbing labels into the lipid matrix. Therefore, cross-relaxation rates contain unbiased information about lateral lipid organization in fluid bilayers. We applied 1H MAS NOESY to complex lipid mixtures which mimic the biological composition of vertebrate rod outer segment (ROS) disk membranes (Huster et al., 1998, 2000). The major phospholipids of the retina are PC/PE/PS at a molar ratio of 4/4/1 (Fliesler and Anderson, 1983). The majority of ROS phospholipids contain a saturated chain in sn-1 position (typically stearic or palmitic acid) and a six-fold unsaturated docosahexaenoic acid (DHAn3) chain in sn-2 position (Albert et al., 1998). Cholesterol content varies between 5 and 25 mol% (Boesze-Battaglia et al., 1990).

To record the cross-relaxation rate between cholesterol and either PC, PE, or PS in the mixture, one phospholipid had protonated stearic acid chains at position sn-1 while the other two had deuterated chains. Switching the label between lipid species yielded cross-relaxation rates between cholesterol and stearic acid of all three lipids in the PC/PE/PS/cholesterol mixture. Results indicate that cholesterol prefers interaction with PC, followed by PE, and lowest probability of interaction for PS (Huster et al., 1998).

1H MAS NOESY reports also probabilities of contact between cholesterol and saturated vs. unsaturated chains. The comparison of cross-relaxation rates indicated some preference for contacts between cholesterol and saturated chains. However, the non-vanishing cross-relaxation between cholesterol and resonances of polyunsaturated chains shows that DHAn3-cholesterol interactions also occur, albeit at a lower probability. Most likely, the flat ring system of cholesterol has stronger attractive interactions with saturated chains compared to cis-polyunsaturated DHAn3 chains. The preference of interactions between cholesterol and PC in mixed polyunsaturated bilayers was confirmed by 2H NMR order parameter measurements on PC/PE/PS/cholesterol mixtures. After cholesterol addition sn-1 chain order of PC increased the most, followed by PE and PS (Huster et al., 1998, 2000).

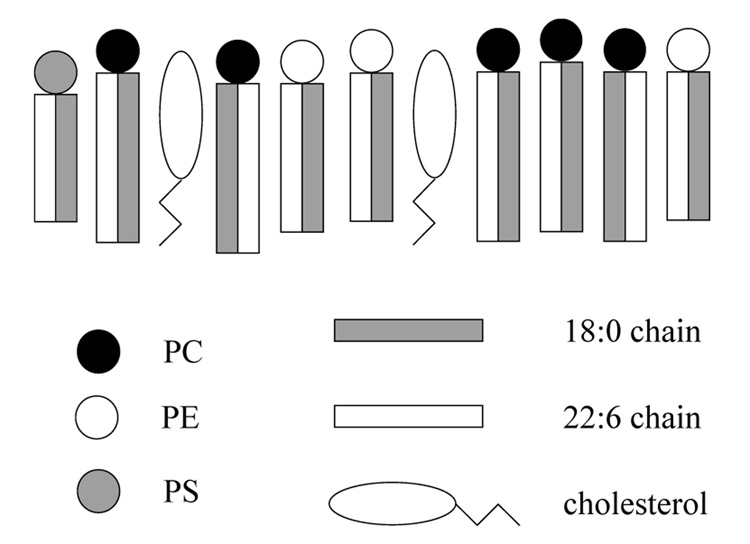

The non-randomness of lateral lipid distribution in a PC/PE/PS/cholesterol mixture is shown as cartoon in Fig. 11. We propose existence of short-lived, fluid lipid clusters with cholesterol at the core, preferentially surrounded by PC molecules. The mixed-chain PCs turn their saturated fatty acids preferentially to cholesterol.

Fig. 11.

Representation of the inhomogeneity of the mixture of polyunsaturated phosphatidylcholine, phosphatidylethanolamine, phosphatidylserine, and cholesterol. Cholesterol shows a preference for the interaction with the saturated chains of the mixed-chain PC. This results in the formation of short-lived PC/cholesterol domains. Contacts between cholesterol and PE and PS also occur but with a lower probability (Huster et al., 1998).

Interaction of polyunsaturated phospholipids with the GPCR rhodopsin

Rhodopsin, the mammalian dim-light photoreceptor, is the best studied GPCR and the only one for which well-resolved crystal structures of the dark adapted state are available. Absorption of light leads to formation of an active, G-protein binding-competent, meta-II state (MII) of rhodopsin in equilibrium with an inactive meta-I state (MI). Dietary studies and in vitro biophysical studies have underlined the critical role of membrane composition during the early steps of the visual process. Lipids not only passively host and solvate membrane proteins, but may play specific roles in structural transitions of membrane proteins. They interact with proteins via non-covalent, hydrophobic, and electrostatic interactions as well as via hydrogen bonds. Lipids with DHAn3 chains shift the MI-MII equilibrium of rhodopsin toward the active MII state (Mitchell et al., 2003). Here we review our recent results on polyunsaturated lipid-rhodopsin interaction obtained by solid state NMR. The following questions guided our research: shall we consider the rhodopsin–lipid interface as homogeneous without preference for a particular type of lipid or is this interface heterogeneous with specific, spatially distinct sites on the protein for interaction with certain lipid species? Does rhodopsin have specific sites for interaction with polyunsaturated DHAn3 chains and what are the properties of those sites? What are the motional properties of DHAn3 acyl chains in the annulus surrounding rhodopsin and away from the protein? What is the lifetime of rhodopsin-DHAn3 associations?

Functional reconstitution of GPCR into AAO-supported single bilayers

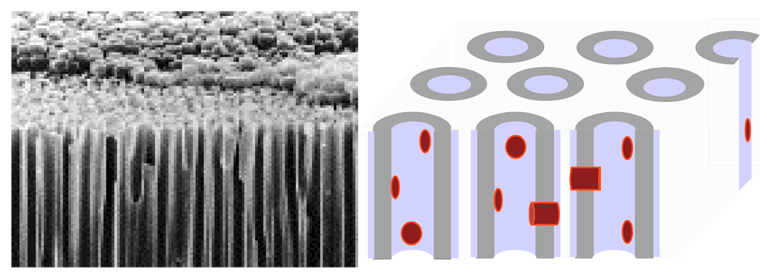

It is desirable to study interaction of lipids with GPCR in single lipid bilayers that are freely accessible from solution and unperturbed by a solid support. At the same time, preparations must reach sufficiently high concentration to enable experiments by methods that require higher concentrations of membrane material such as NMR. Although sensitivity of modern high-field NMR equipment has increased, sample size is still in the micro- to milligram range. Porous anodic aluminum oxide (AAO) filters (Whatman Inc., Florham Park, NJ) offer a convenient way to prepare oriented, solid-supported bilayers. Porous AAO has high concentration of ~200 nm-size pores that traverse the AAO substrate. The pore walls of AAO are easily coated with single lipid bilayers of tubular geometry (Gaede et al., 2004; Soubias et al., 2006a).

The pathway for reconstitution of membrane proteins into porous AAO involves solubilization of the protein in detergent micelles, addition of phospholipids at the proper lipid/protein ratio, formation of liposomes by dilution of the micellar solution below the critical micelle concentration, deposition of membranes into AAO pores by extrusion, and removal of residual detergent by flushing of filters with buffer (Soubias et al., 2006a).

Before the reconstitution experiments we investigated bilayers of the model lipid 16:0–18:1n9-PC (POPC) without protein in AAO pores (Gaede et al., 2004). One square centimeter of AAO filter with a thickness of 60 µm yielded up to 500 cm2 of tubular, oriented single bilayers. Used as single filter or as stack of several filters, the amount of lipid is sufficient for 1H-, 2H-, 31P-, and 13C solid state NMR studies.

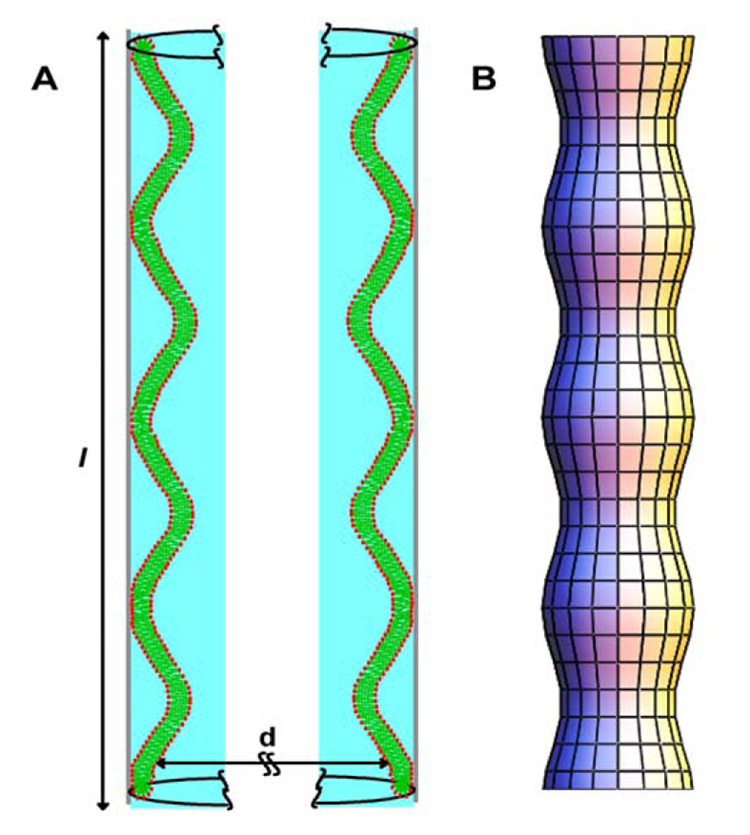

The orientation of bilayer normals derived from 2H NMR spectra of deuterated lipids indicates adsorption of tubular bilayers inside AAO pores. The mosaic spread of bilayer orientations suggests that tubules are wavy as shown in Fig. 13. We successfully studied deposited membranes by 1H MAS NMR, taking advantage of the improved resolution and signal intensity afforded by MAS. By 1H-MAS NMR diffusion experiments with application of pulsed magnetic field gradients (Gaede and Gawrisch, 2003, 2004; Gaede et al., 2004) we determined that lipid diffusion along the pore axis is restricted to distances of less than one micrometer, suggesting that lipid tubules are discontinuous (Gaede et al., 2004). Furthermore, by 2H NMR experiments on headgroup deuterated POPC and 1H MAS NMR experiments we established that lipid tubules are separated from the AAO surface by a thick water cushion over most of their length that prevents perturbation of the lipid matrix by the solid support. The ends of tubules are well sealed against the pore surface. We successfully entrapped water soluble polymers (MW 8,000) in the water between the solid support and the lipid tubules (Gaede et al., 2004). The water inside lipid tubules is easily exchangeable by flushing the filers gently as demonstrated by 1H- and 31P-MAS NMR studies with application of paramagnetic ions (Gaede et al., 2004).

Fig. 13.

A) Model for lipid adsorption to the surface of pores in AAO consistent with the NMR data. A single bilayer forms a good seal with the AAO surface by the interaction of a small percentage of the lipids. The lipids adsorb as wavy tubules with an average length of 0.4 µm. According to our 2H NMR and 1H-MAS NMR experiments, these tubules posses undulation with a radius of curvature of 100 – 400 nm. Trapped between the tubules and the AAO surface are pockets of water with an average thickness of 3 nm. B) Illustration of shape of the lipid bilayer tubules inside the AAO pore. Such lipid cylinders with variable diameter have lowest free energy if they belong to the family of surfaces with constant total curvature, called Delaunay surfaces (Gaede et al., 2004).

Those unperturbed, solid supported membranes are ideal for incorporation of membrane spanning proteins with large intra- and extracellular domains like GPCR. We successfully reconstituted membranes containing bovine rhodopsin (Soubias et al., 2006a) as well as the recombinant cannabinoid receptor CB2 (Yeliseev et al., 2005). In ligand- and G-protein binding studies we observed that the aluminum oxide surface did not perturb GPCR function (Soubias et al., 2006a; Yeliseev et al., 2005). Considering the ease of sample preparation, protein containing biomembranes supported by the porous aluminum oxide filters have considerable promise for use in structural studies. For membranes containing bovine rhodopsin at a rhodopsin/lipid molar ratio of 1/100 we determined that 160 µg of rhodopsin and 320 µg of lipid per square centimeter of AAO filter were deposited corresponding to almost complete coverage of inner pore surfaces with a lipid bilayer (Soubias et al., 2006a). Considering that up to 100 filters may be stacked in the NMR probe, AAO-supported samples may be suitable for experiments on both lipids and membrane proteins.

Here we used porous AAO for rapid preparation of detergent-free, rhodopsin containing bilayers. The time consuming step in the preparation of reconstituted samples is detergent removal by dialysis. For bilayers supported by porous AAO, gentle flushing of pores with buffer is sufficient to remove detergents within minutes. This not only speeds up sample preparation, it also reduces chances that polyunsaturated lipids are oxidized during sample preparation.

Are rhodopsin-DHAn3 interactions specific?

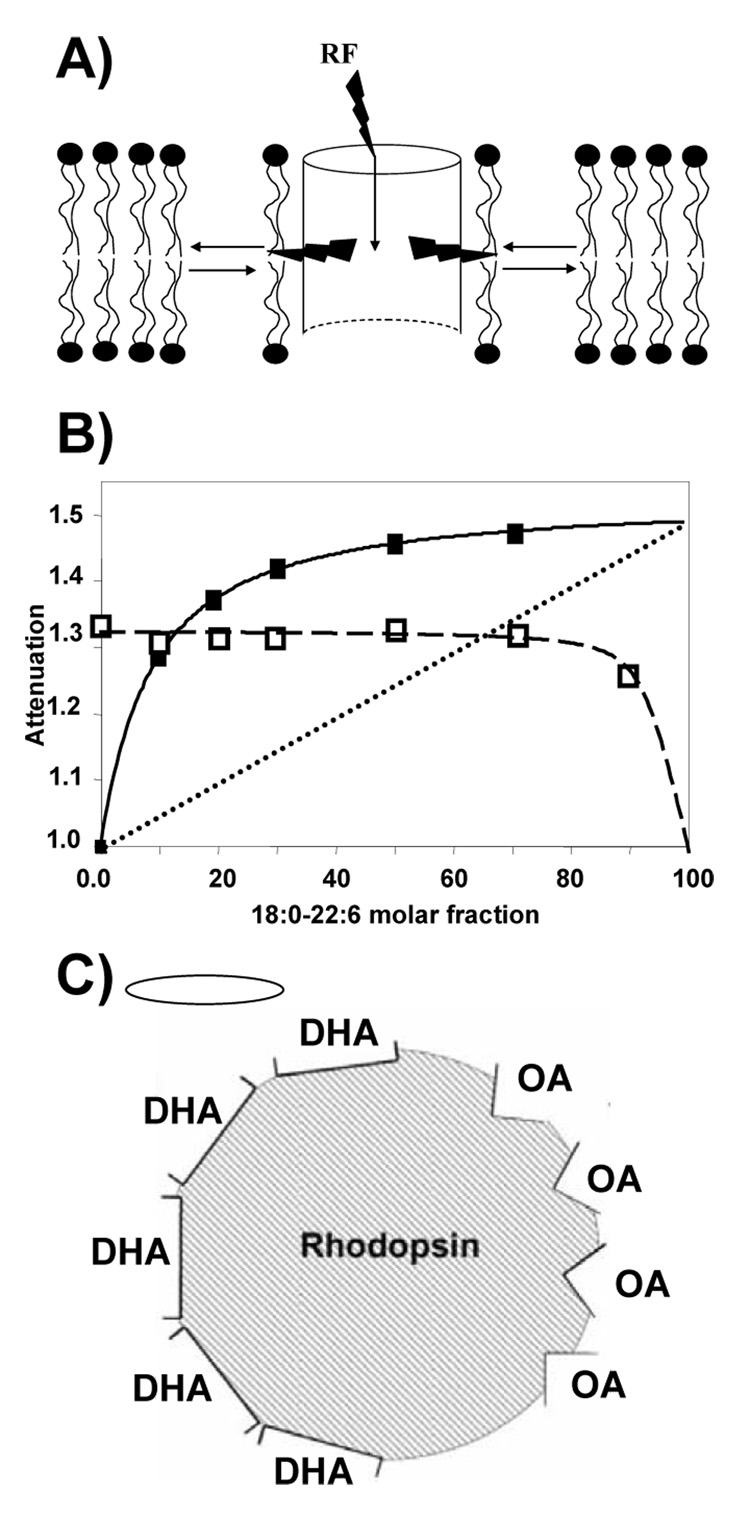

To tackle this question, we adapted the Saturation-Transfer Difference NMR experiment (Forsen and Hoffman, 1963) that is widely used for protein-ligand binding studies in solution to solid state 1H-MAS NMR. The principle features of saturation transfer (ST) experiments are explained in Fig. 14A (Soubias and Gawrisch, 2005; Soubias et al., 2006b). In brief, protein resonances are selectively saturated via Gaussian-shaped, frequency selective radiofrequency (rf) pulses. Magnetization redistributes within the protein via spin diffusion and is partially transferred from the protein to a first layer of lipids surrounding the protein via intermolecular 1H-1H dipolar interactions. Efficient intermolecular magnetization transfer from protein to lipid requires short distances between protons, equivalent to physical contact between molecules. While saturation energy continues to enter the system through the sustained application of a rf signal, chemical exchange of lipids between the first layer and the surrounding lipid matrix takes place which raises the population of rf-saturated lipids. Lipid-protein contacts are detected through changes of lipid resonance intensities after application of a π/2 hard pulse. Signal intensities between experiments with and without selective pre-saturation of protein are compared.

Fig. 14.

(A) Schematics of magnetization flow in the 1H-STD-MAS NMR experiment. Membrane protein resonances are selectively saturated via frequency selective radio frequency (rf) pulses. The magnetization redistributes within the protein via spin diffusion. Magnetization is then transferred from the protein to a first layer of lipids surrounding the protein via 1H-1H spin dipolar contacts. Efficient magnetization transfer requires lipid-protein distances of 5 Å or less and depends on molecular properties of lipids and protein. While saturation energy continues to enter the system through the sustained application of a rf signal, exchange of lipids between the first layer and the surrounding lipid matrix takes place, thus increasing the population of rf-saturated lipid. If the lifetime of lipid-protein interaction is much shorter than the saturation time then all lipids in the matrix may reach the protein, and the fractional decline of lipid resonance intensity is a measure of the probability for a specific lipid to interact with the protein (Soubias and Gawrisch, 2005). (B) Saturation of DHAn3 chains (filled squares) and of oleic acid chains (open squares) as a function of 18:0–22:6n3-PC concentration in 18:0–22:6n3-PC/16:0–18:1n9-PC reconstituted membranes containing one rhodopsin molecule per 250 lipids. Saturation of polyunsaturated DHA has a strong non-linear dependence on concentration, indicating preferential interaction with rhodopsin. The dotted line indicates how saturation would depend on 18:0–22:6n3-PC concentration without preferential interaction. Oleic acid receives its magnetization from a different site on the protein. (C) The lipid-rhodopsin interface is heterogeneous with sites for semi-specific interaction for DAHn3 and oleic acid (Soubias et al., 2006b).

Magnetization flows mostly from sites where lipid-protein distances are smaller, area of contacts larger, and lipid immobilization is stronger. It makes ST NMR an efficient probe for sites on the protein that engage in specific interaction with lipids. Since magnetization transfer is modulated by differences in strength of lipid-protein interaction, results do not necessarily report lipid composition of the protein annulus.

The interaction of bovine rhodopsin with poly- and monounsaturated lipids was studied on bovine rod outer segment (ROS) disks and on binary mixtures of phospholipids with DHAn3 and oleic acid (OA) chains at position sn-2. Fig. 14B shows the dependence of DHAn3 and OA resonance attenuation as a function of DHAn3 mole fraction in the mixture. The DHAn3 resonance attenuation increases stronger than linear with increasing DHAn3 content until it reaches saturation at concentrations near 50 mol%. This indicates that DHA interacts with a limited number of sites on rhodopsin with high affinity for DHAn3.

If OA would receive magnetization from the same sites then its attenuation would have decreased correspondingly. However this is not the case. A decline of OA attenuation is observed at very high concentration of DHAn3-containg lipids only. In other words, poly- and monounsaturated lipids interact specifically with a few, spatially separate sites on rhodopsin. The experiments show that the lipid-rhodopsin interface is heterogeneous with a small number of sites for specific interaction with polyunsaturated lipids (Fig. 14C). Experiments conducted on ROS disk membranes with photoactivation demonstrated that all photointermediates transferred magnetization preferentially to DHAn3 chains, but highest rates were observed for Meta-III rhodopsin.

Rates of magnetization transfer from protein to DHAn3 are lipid headgroup-dependent and increase in the sequence PC<PS<PE suggesting that headgroups modulate lipid-rhodopsin interaction as well (Soubias et al., 2006b).

Do lipid-rhodopsin interactions alter DHAn3 dynamics?

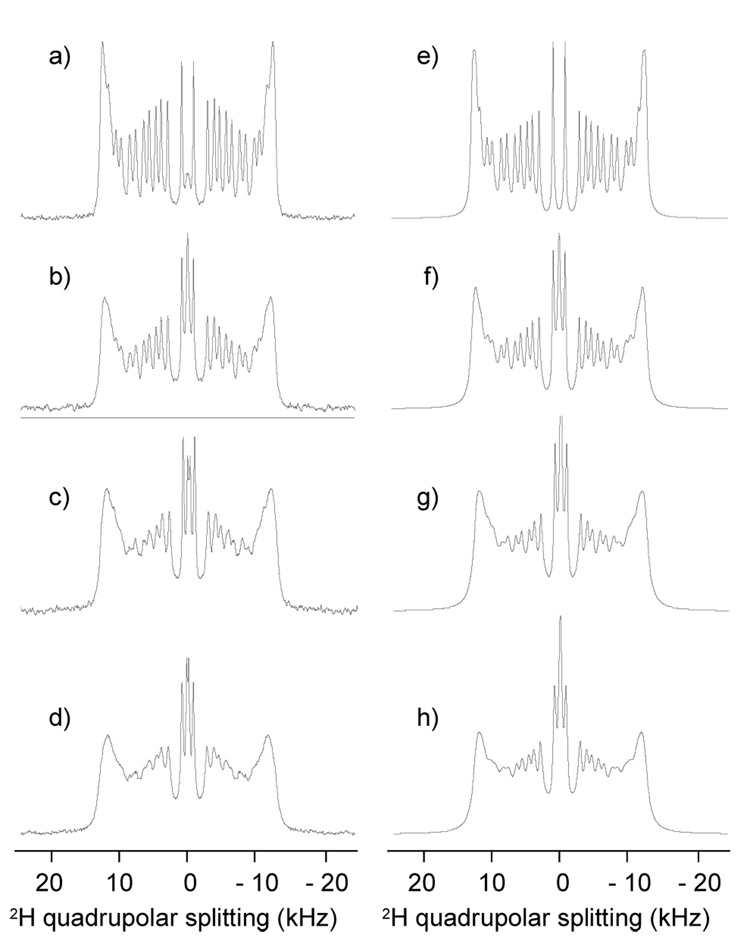

2H NMR is a powerful tool to probe lipid dynamics on a time scale of 10−4–10−5 s. In Fig. 15 2H spectra of 18:0(d35)-22:6n3-PC membranes with and without rhodopsin are shown. Although spectra of rhodopsin-containing bilayers are somewhat broadened, spectral simulations revealed that they stem from a single set of quadrupolar splittings and that order parameters are almost unchanged by the presence of protein. Therefore acyl chains explore the same conformational space near the protein and away from it, and protein annular lipids are in fast exchange with the lipid matrix on a time scale of 10−4 s. But, lipid-rhodopsin interaction increases mosaic spread of bilayer orientations, or in other words, rhodopsin enhances waviness of the membrane. We also observed reduced 2H transverse relaxation times, T2, visible as line broadening.

Fig. 15.

(Left) Experimental 2H NMR spectra of sn-1 chain perdeuterated 18:0–22:6n3-PC-rhodopsin tubular bilayers reconstituted into AAO filters at a rhodopsin/lipid molar ratio of 0 (a), 0.001 (b), 0.005 (c) and 0.01 (d). Samples were oriented in the magnetic field such that the axis of pores was oriented parallel to the magnetic field B0. The quadrupolar splittings correspond to an orientation of bilayer normals perpendicular to the field confirming the tubular geometry of lipid bilayers inside the pores. (Right, e, f, g, h) Simulated 2H spectra (Soubias et al., 2006a).

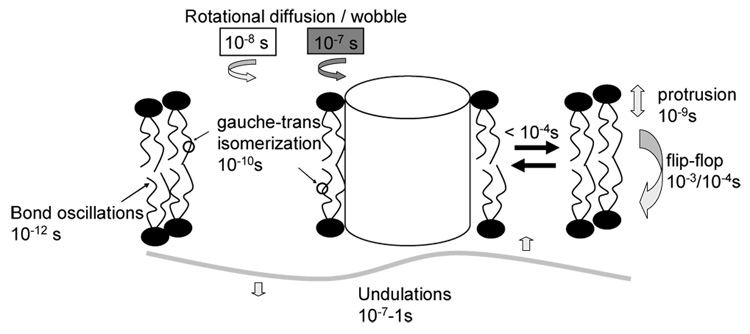

More insight into motional properties of annular DHAn3 is obtained from 13C NMR T1 and T2 relaxation measurements. NMR relaxation yields information on chain dynamics on the timescale from pico- to the milliseconds. Chain dynamics in lipid bilayers are characterized by superposition of motions: H-C bond orientational flicker and C-C bond isomerization, 10−12<t<10−10 s; lipid axial reorientation and tumble; 10−9< t < 10−7 ns; and bilayer undulation, 10−7 < t < 1 s (see Fig. 16). Fast motions with correlation times on the order of one nanosecond reduce both longitudinal, T1, and transverse, T2, relaxation times. But only T2 is sensitive to collective lipid motions with longer correlation times from 10−8 to 10−4 s.

Fig. 16.

Motional correlation times in rhodopsin-containing lipid bilayers. 2H and 13C NMR experiments demonstrate that boundary lipids are in fast exchange with lipids in the bulk, and that rhodopsin does not measurably alter rates of DHAn3 vinyl bond isomerization. However, the protein increases motional correlation times of collective modes of lipid motion, e.g. bilayer undulations, or increase their amplitudes.

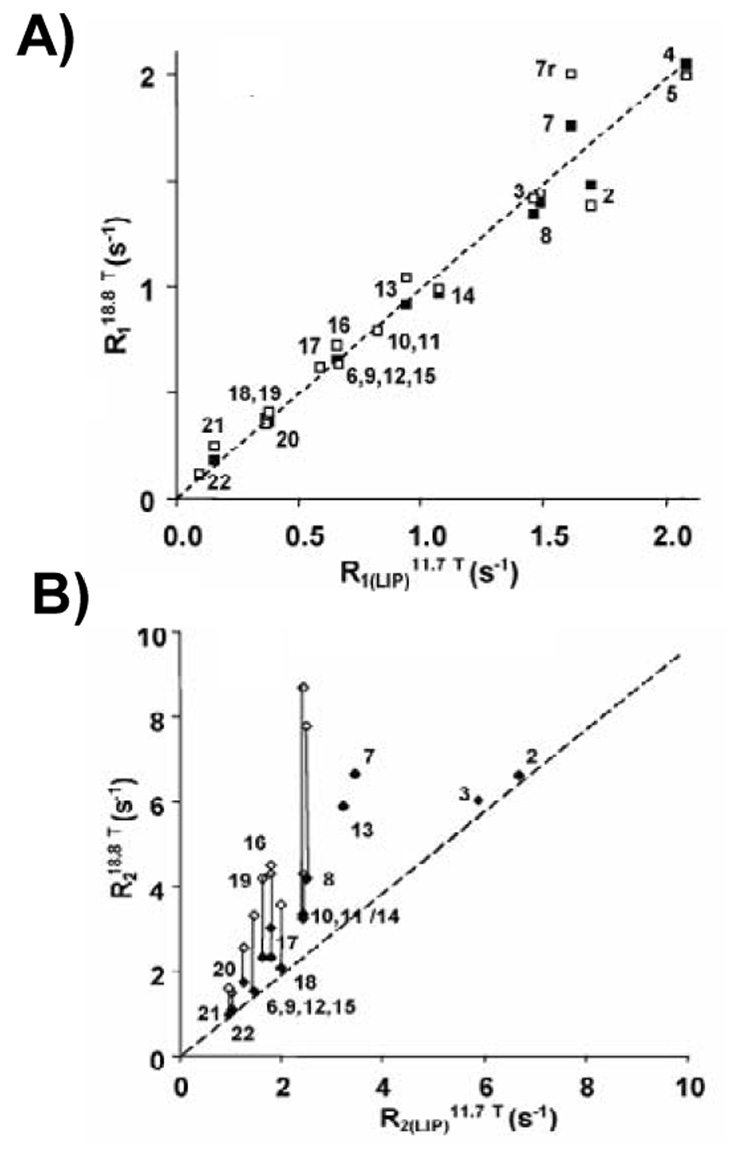

Figures 17A, B compare R1 and R2 of each carbon of DHAn3 acyl chains measured at two different magnetic fields, 11.7 and 18.7 T, with and without rhodopsin. In the presence of rhodopsin, R1 values remain unchanged and stay field independent (Fig. 17A), indicating that rates of bond isomerization remain in the range of 10−12–10−11 s. However, rhodopsin increases R2 values, indicating changes of spectral density on a time scale from 10−8 − 10−4s corresponding to slower, collective modes of lipid motion. Most likely, rhodopsin-lipid interactions decrease correlation times of lipid tumble in the annulus of rhodopsin by one order of magnitude (Fig. 17B).

Fig. 17.

Plot of spin-lattice (A) and spin-spin (B) 13C NMR relaxation rates of the DHAn3 chain in 18:0(d35)-22:6n3-PC bilayers measured at two values of magnetic field strength, 11.7 T (x-axis) and 18.8 T (y-axis) with (open symbols) and without rhodopsin (filled symbols). While spin-lattice relaxation times show no magnetic field dependence, confirming that spin-lattice relaxation is dominated by motions on the sub-nanosecond timescale, the spin-spin relaxation times have some field dependence (Soubias and Gawrisch, 2007).

Modes of DHAn3-rhodopsin interaction

Our results have shown that DHAn3-containing lipids may interact with particular sites on rhodopsin. Interactions are weakly specific. However, those sites appear to be few, lipids in the annulus around rhodopsin are in rapid exchange with the rest of the lipid matrix, and overall, motional inhibition of polyunsaturated chains from interaction with rhodopsin is insignificant. We may not exclude that the resonances of a very small number of lipids, less than ten per rhodopsin, are severely broadened. If such lipids remain associated with rhodopsin for milliseconds and longer, their resonances could be obscured. But this is a purely hypothetical consideration.

DHAn3 hydrocarbon chains in lipid bilayers explore their conformational space on the timescale of nanoseconds. Despite their six cis-locked double bonds, conformational transitions are more rapid, making polyunsaturated bilayers far more dynamic than their monounsaturated and saturated counterparts. Even the loss of a single double bond from DHAn-3 to DPAn6 matters for lipid dynamics but also for chain density distribution in bilayers.

Such redistribution is expected to change the balance of repulsive and attractive interactions between lipids in bilayers that are summarized in so-called lateral pressure profiles. Indeed, recent theoretical calculations for 18:0–22:6n3-PC and 18:0–22:5n6-PC bilayers, using results from the molecular simulations conducted at the Feller lab, confirmed that DHAn3 to DPAn6 replacement alters pressure profiles (Carillo-Tripp and Feller, 2005). The lipid lateral area per molecule is a delicate balance of attractive and repulsive forces. Compression results from the hydrophobic effect at the lipid water interface and attractive van der Waals forces between lipids. Expansion arises from the repulsive steric interactions between the fluid lipid segments. Although attractive and repulsive forces cancel over the thickness of a lipid monolayer, the point of action of attractive and repulsive forces is not identical, resulting in a moment of force which bends lipid monolayers. Lipid bilayers composed of such curvature prone lipids are under curvature elastic stress. Calculations using protein models confirmed that the magnitude of curvature stress in polyunsaturated membranes is sufficiently large to alter GPCR activation (Huber et al., 2004).

However, treatment of the rhodopsin-lipid interface as uniform in terms of lipid-protein interaction is no longer justified. Also, an influence on protein function from weakly specific lipid-protein interactions at particular sites must be considered.

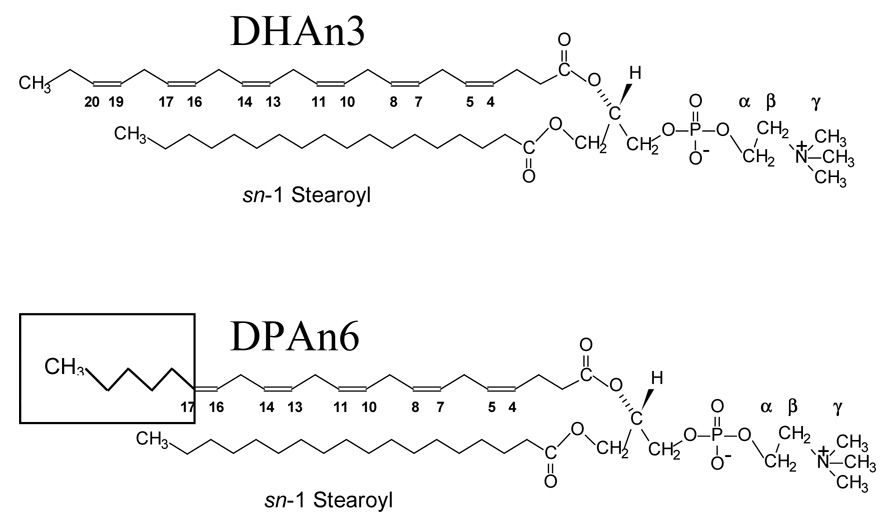

Fig. 1.

Chemical structure of polyunsaturated lipids; DHAn3: 1-stearoyl-2-docosahexaenoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (18:0–22:6n3-PC); DPAn6: 1-stearoyl-2-docosapentaenoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (18:0–22:5n6-PC).

Fig. 3.

The 13C MAS NMR spectrum of 18:0(d35)-22:6n3-PC in 50 wt.% D2O with signal assignments of olefin carbons. Ten out of twelve olefin resonances are fully resolved (Eldho et al., 2003).

Fig. 6.

Spin-lattice relaxation times T1 of docosahexaenoic acid (DHAn3, 22:6n3) and docosapentaenoic acid (DPAn6, 22:5n6) in 18:0–22:6n3-PC and 18:0–22:5n6-PC bilayers, respectively (Eldho et al., 2003). The double bonds of DHAn3 are labeled with bars and numbers.

Fig. 8.

The flexible links in docosahexaenoic acid (22:6n3, DHAn3) and docosapentaenoic acid (22:5n6, DPAn6).

Fig. 10.

Schematic presentation of the density differences between stearic acid (SA) and the polyunsaturated DHAn3 and DPAn6 chains over the hydrophobic thickness of a monolayer. The volume density of polyunsaturated chains is higher at the lipid water interface, while density of the saturated chain is higher in the bilayer center. The loss of a single double bond from DHAn3 to DPAn6 tends to equalize the differences in chain distributions (Eldho et al., 2003).

Fig. 12.

Left, scanning electron micrograph of highly porous anodic aluminum oxide (AAO, Whatman) filters. The average pore diameter is 200 nm. Right, single lipid bilayers of tubular geometry with incorporated GPCR inside the porous substrate.

Acknowledgments

K.G. and O.S. are supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. The AND/R, constructed by the Cold Neutrons for Biology and Technology (CNBT) partnership, is supported by the National Institute of Standards and Technology, the Regents of the University of California, and by a grant from the National Institute for Research Resources awarded to the University of California at Irvine.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Albert AD, Young JE, Paw Z. Phospholipid fatty acyl spatial distribution in bovine rod outer segment disk membranes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1998;1368:52–60. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(97)00200-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Applegate KR, Glomset JA. Computer-based modeling of the conformation and packing properties of docosahexaenoic acid. J.Lipid.Res. 1986;27:658–680. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binder H, Gawrisch K. Dehydration induces lateral expansion of polyunsaturated 18 : 0–22 : 6 phosphatidylcholine in a new lamellar phase. Biophys. J. 2001;81:969–982. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)75755-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boesze-Battaglia K, Fliesler SJ, Albert AD. Relationship of cholesterol content to spatial distribution and age of disc membranes in retinal rod outer segments. J.Biol.Chem. 1990;265:18867–18870. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown MF. Theory of spin-lattice relaxation in lipid bilayers and biological membranes - 2H and 14N quadrupolar relaxation. J. Chem. Phys. 1982;77:1576–1599. [Google Scholar]

- Brown MF, Chan SI, Gran DM, Harris RK. Bilayer Membranes: deuterium & carbon-13 NMR Encyclopedia of Nuclear Magnetic Resonance. New York: Wiley; 1995. pp. 871–885. [Google Scholar]

- Brown MF, Ribeiro AA, Williams GD. New view of lipid bilayer dynamics from 2H and 13C NMR relaxation time measurements. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1983;80:4325–4329. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.14.4325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carillo-Tripp M, Feller SE. Evidence for a mechanism by which ω-3 polyunsaturated lipids may affect membrane protein function. Biochemistry. 2005;44:10164–10169. doi: 10.1021/bi050822e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eldho NV, Feller SE, Tristram-Nagle S, Polozov IV, Gawrisch K. Polyunsaturated docosahexaenoic vs docosapentaenoic acid - Differences in lipid matrix properties from the loss of one double bond. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:6409–6421. doi: 10.1021/ja029029o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feller SE, Gawrisch K, MacKerell AD. Polyunsaturated fatty acids in lipid bilayers: Intrinsic and environmental contributions to their unique physical properties. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:318–326. doi: 10.1021/ja0118340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feller SE, Gawrisch K, Woolf TB. Rhodopsin exhibits a preference for solvation by polyunsaturated docosohexaenoic acid. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:4434–4435. doi: 10.1021/ja0345874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feller SE, Huster D, Gawrisch K. Interpretation of NOESY cross-relaxation rates from molecular dynamics simulation of a lipid bilayer. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999;121:8963–8964. [Google Scholar]

- Fliesler SJ, Anderson RE. Chemistry and metabolism of lipids in the vertebrate retina. Prog. Lipid Res. 1983;22:79–131. doi: 10.1016/0163-7827(83)90004-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forsen S, Hoffman RA. Study of moderately rapid chemical exchange reactions by means of nuclear magnetic double resonance. J. Chem. Phys. 1963;39:2892–2901. [Google Scholar]

- Gaede HC, Gawrisch K. Lateral diffusion rates of lipid, water, and a hydrophobic drug in a multilamellar liposome. Biophys. J. 2003;85:1734–1740. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)74603-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaede HC, Gawrisch K. Multi-dimensional pulsed field gradient magic angle spinning NMR experiments on membranes. Magn.Reson.Chem. 2004;42:115–122. doi: 10.1002/mrc.1329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaede HC, Luckett KM, Polozov IV, Gawrisch K. Multinuclear NMR studies of single lipid bilayers supported in cylindrical aluminum oxide nanopores. Langmuir. 2004;20:7711–7719. doi: 10.1021/la0493114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gawrisch K. The dynamics of membrane lipids. In: Yeagle PL, editor. The structure of biological membranes. vol 2. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 2005. pp. 147–171. [Google Scholar]

- Gawrisch K, Eldho NV, Polozov IV. Novel NMR tools to study structure and dynamics of biomembranes. Chem.Phys.Lipids. 2002;116:135–151. doi: 10.1016/s0009-3084(02)00024-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross JD, Warschawski DE, Griffin RG. Dipolar recoupling in MAS NMR: a probe for segmental order in lipid bilayers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997;119:796–802. [Google Scholar]

- Gunstone FD. 1H-NMR and 13C-NMR spectra of 6 n-3 polyene esters. Chem. Phys. Lipids. 1990;56:227–229. [Google Scholar]

- Holte LL, Peter SA, Sinnwell TM, Gawrisch K. 2 H nuclear magnetic resonance order parameter profiles suggest a change of molecular shape for phosphatidylcholines containing a polyunsaturated acyl chain. Biophys. J. 1995;68:2396–2403. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(95)80422-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber T, Botelho AV, Beyer K, Beyer MF. Membrane model for the G-protein-coupled receptor rhodopsin: Hydrophobic interface and dynamical structure. Biophys. J. 2004;86:2078–2100. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(04)74268-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huster D, Arnold K, Gawrisch K. Influence of docosahexaenoic acid and cholesterol on lateral lipid organization in phospholipid mixtures. Biochemistry. 1998;37:17299–17308. doi: 10.1021/bi980078g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huster D, Arnold K, Gawrisch K. Investigation of lipid organization in biological membranes by two-dimensional nuclear Overhauser enhancement spectroscopy. J. Phys. Chem. B. 1999;103:243–251. [Google Scholar]

- Huster D, Arnold K, Gawrisch K. Strength of Ca2+ binding to retinal lipid membranes: Consequences for lipid organization. Biophys. J. 2000;78:3011–3018. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76839-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huster D, Gawrisch K. NOESY NMR crosspeaks between lipid headgroups and hydrocarbon chains: spin diffusion or molecular disorder? J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999;121:1992–1993. [Google Scholar]

- Klauda JB, Eldho NV, Gawrisch K, Brooks BR, Pastor RW. Collective and noncollective models of NMR relaxation in lipid vesicles and multilayers. J. Phys. Chem. 2007 doi: 10.1021/jp075641w. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipari G, Szabo A. Model-free approach to the interpretation of nuclear magnetic resonance relaxation in macromolecules .1. Theory and Range of Validity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1982;104:4546–4559. [Google Scholar]

- Lyatskaya Y, Liu YF, Tristram-Nagle S, Katsaras J, Nagle JF. Method for obtaining structure and interactions from oriented lipid bilayers. Phys. Rev. 2001:E 6301. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.63.011907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mihailescu M, Gawrisch K. The structure of polyunsaturated lipid bilayers important for rhodopsin function - a neutron diffraction study. Biophys. J. 2006;90:L4–L6. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.071712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell DC, Niu SL, Litman BJ. DHA-rich phospholipids optimize G-Protein-coupled signaling. J Pediatr. 2003;143:S80–S86. doi: 10.1067/s0022-3476(03)00405-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohrhauer H, Holman RT. Alteration of fatty acid composition of brain lipids by varying levels of dietary essential fatty acids. J.Neurochem. 1963;10:523–530. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1963.tb09855.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa Y, Utsumi H, Inoue K, Nojima S. Transfer of cholestane spin label between lipid bilayer membranes and its molecular motion in membranes. J. Biochem. 1979;86:783–787. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a132585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabinovich AL, Ripatti PO. On the conformational, physical properties and functions of polyunsaturated acyl chains. Biochim.Biophys Acta. 1991;1085:53–62. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(91)90231-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rujanavech C, Silbert DF. Effect of sterol structure on the partition of sterol between phospholipid vesicles of different composition. J Biol.Chem. 1986;261:7215–7219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salem N, Litman B, Kim HY, Gawrisch K. Mechanisms of action of docosahexaenoic acid in the nervous system. Lipids. 2001;36:945–959. doi: 10.1007/s11745-001-0805-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaikh SR, Cherezov V, Caffrey M, Soni SP, LoCascio D, Stillwell W, Wassall SR. Molecular organization of cholesterol in unsaturated phosphatidylethanolamines: X-ray diffraction and solid state H-2 NMR reveal differences with phosphatidylcholines. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:5375–5383. doi: 10.1021/ja057949b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaikh SR, Dumaual AC, Castillo A, LoCascio D, Siddiqui RA, Stillwell W, Wassall SR. Oleic and docosahexaenoic acid differentially phase separate from lipid raft molecules: A comparative NMR, DSC, AFM, and detergent extraction study. Biophys. J. 2004;87:1752–1766. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.044552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smaby JM, Momsen MM, Brockman HL, Brown RE. Phosphatidylcholine acyl unsaturation modulates the decrease in interfacial elasticity induced by cholesterol. Biophys. J. 1997;73:1492–1505. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78181-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soubias O, Gawrisch K. Probing specific lipid-protein interaction by saturation transfer difference NMR spectroscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:13110–13111. doi: 10.1021/ja0538942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soubias O, Gawrisch K. Docosahexaenoyl chains isomerize on the sub-nanosecond time scale. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:6678–6679. doi: 10.1021/ja068856c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soubias O, Polozov IV, Teague WE, Yeliseev AA, Gawrisch K. Functional reconstitution of rhodopsin into tubular lipid bilayers supported by nanoporous media. Biochemistry. 2006a;45:15583–15590. doi: 10.1021/bi061416d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soubias O, Teague WT, Gawrisch K. Evidence for specificity in lipid-rhodopsin interactions. J. Biol. Chem. 2006b doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603059200. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiener MC, King GI, White SH. Structure of a fluid dioleoylphosphatidylcholine bilayer determined by joint refinement of x-ray and neutron diffraction data. I. Scaling of neutron data and the distributions of double bonds and water. Biophys. J. 1991;60:568–576. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(91)82086-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Worcester DL, Franks NP. Structural analysis of hydrated egg lecithin and cholesterol bilayers. II Neutron Diffraction. J.Mol.Biol. 1976;100:359–378. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(76)80068-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yau WM, Gawrisch K. Lateral lipid diffusion dominates NOESY cross-relaxation in membranes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000;122:3971–3972. [Google Scholar]

- Yeliseev AA, Wong K, Soubias O, Gawrisch K. Expression of human peripheral cannabinoid receptor for structural studies. Protein Sci. 2005;14:2638–2653. doi: 10.1110/ps.051550305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]