Abstract

OBJECTIVE—The purpose of this study was to examine the association between fruit, vegetable, and fruit juice intake and development of type 2 diabetes.

RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS—A total of 71,346 female nurses aged 38–63 years who were free of cardiovascular disease, cancer, and diabetes in 1984 were followed for 18 years, and dietary information was collected using a semiquantitative food frequency questionnaire every 4 years. Diagnosis of diabetes was self-reported.

RESULTS—During follow-up, 4,529 cases of diabetes were documented, and the cumulative incidence of diabetes was 7.4%. An increase of three servings/day in total fruit and vegetable consumption was not associated with development of diabetes (multivariate-adjusted hazard ratio 0.99 [95% CI 0.94–1.05]), whereas the same increase in whole fruit consumption was associated with a lower hazard of diabetes (0.82 [0.72–0.94]). An increase of 1 serving/day in green leafy vegetable consumption was associated with a modestly lower hazard of diabetes (0.91 [0.84–0.98]), whereas the same change in fruit juice intake was associated with an increased hazard of diabetes (1.18 [1.10–1.26]).

CONCLUSIONS—Consumption of green leafy vegetables and fruit was associated with a lower hazard of diabetes, whereas consumption of fruit juices may be associated with an increased hazard among women.

The worldwide burden of type 2 diabetes has increased rapidly in tandem with increases in obesity. The most recent estimate for the number of people with diabetes worldwide in 2000 was 171 million, and this number is projected to increase to at least 366 million by the year 2030 (1). Fruit and vegetable consumption has been associated with decreased incidence of and mortality from a variety of health outcomes including obesity, hypertension, and cardiovascular diseases in epidemiological studies (2–4). However, few prospective studies have examined the relationship between fruit and vegetable intake and risk of diabetes, and the results are not entirely consistent (5–10).

Differences in the nutrient contents of fruits and vegetables by group could lead to differences in health effects. Furthermore, the role of fruit juices could be important and has not been well studied. Although fruit juices may have antioxidant activity (11), they lack fiber, are less satiating, and tend to have high sugar content. To further explore the role of fruit and vegetable consumption in the development of diabetes, we examined the association between intake of all fruits and vegetables, specific groups of fruits and vegetables, and fruit juices among women enrolled in the Nurses' Health Study diet cohort.

RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS—

The Nurses' Health Study was established in 1976 with responses of 121,700 female registered nurses between the ages of 30 and 55 years from 11 different U.S. states to an initial mailed questionnaire regarding medical history, lifestyle, diet, and other health practices. Follow-up questionnaires were mailed every 2 years to update information on health-related behavior and determine incident disease, including diabetes and other chronic diseases. The diet cohort was established in 1980 with 98,462 participants. Of those, 81,757 completed the 1984 questionnaire, had a total energy intake that was between 600 and 3,500 kcal, and left fewer than 12 food items blank (n = 16,705 excluded). We also excluded women who died before the return of the 1984 questionnaire (n = 1); who had diagnosed cardiovascular disease (n = 2,681), cancer (n = 4,218), or diabetes (n = 2,116) at the assessment in 1984; and who were missing date of diagnosis of diabetes (n = 1,395). After these exclusions, a total of 71,346 women (72.5% of the diet cohort) contributed to the analysis, with follow-up completed in June of 2002.

Dietary assessment

A semiquantitative food-frequency questionnaire (FFQ) was included with the general health questionnaire in 1980, 1984, 1986, 1990, 1994, and 1998. The 1980 FFQ contained 61 items, with 6 questions on fruit consumption, 11 on vegetable consumption, and 3 on potato consumption. In 1984, the FFQ was substantially expanded to include 16 questions on fruit consumption, 28 on vegetable consumption, and 3 on potato consumption. In this analysis, we considered 1984 as the baseline because the FFQ remained consistent afterward. Participants were asked to report the frequencies of their consumption of fruit and vegetable items during the previous year. For each fruit or vegetable, a standard unit or portion size was specified. Nine responses were possible, ranging from “never” to “six or more times per day” (12). The response to each food item was converted to average daily intakes and then summed to compute the total intake (fruit juices were not included in total fruit intake or total fruit and vegetable intake). Average daily intakes of foods in specific groups (green leafy vegetables, legumes, and fruit juices) were assessed. Green leafy vegetables included spinach, kale, and lettuces; legumes included tofu, peas, and beans; and fruit juices included apple, orange, grapefruit, and other fruit juices. These categories were modified from those used in a different cohort in an earlier report (13). Potato differs from all other commonly consumed vegetables in energy density, nutrient density, glycemic index and load, and the likelihood of its presence in fast food. Therefore, we did not include potatoes in any vegetable category. The validity of the FFQ has been evaluated in previous studies (14,15).

Assessment of nondietary covariates

Data on BMI, physical activity, smoking status, alcohol use, postmenopausal hormone therapy, family history of diabetes, and physician-diagnosed hypertension and high cholesterol were self-reported on biennial questionnaires. BMI (measured as weight in kilograms divided by the square of height in meters) was calculated by using updated weight information for each time period.

Ascertainment of outcomes

The primary end point was development of type 2 diabetes. At each 2-year cycle, participants were asked whether they had a diagnosis of diabetes. For each self-reported diagnosis of diabetes, a supplemental questionnaire was sent, asking about diabetes symptoms, diagnostic tests, and treatments. A diagnosis of diabetes was accepted when any one of the following criteria was met: 1) one or more classic symptoms of diabetes and reported elevated plasma glucose levels (fasting plasma glucose ≥7.8 mmol/l [140 mg/dl] or randomly measured plasma glucose ≥11.1 mmol/l [200 mg/dl]), 2) reported elevated plasma glucose on at least two occasions in the absence of symptoms, or 3) treatment with oral hypoglycemic medication or insulin. These criteria for diagnosis of diabetes are consistent with those proposed by the National Diabetes Data Group (16) because most cases were diagnosed before 1997. For diagnoses of diabetes established after 1998, the American Diabetes Association criteria (reported fasting plasma glucose ≥7 mmol/l [126 mg/dl]) were used. We excluded women with type 1 diabetes or gestational diabetes mellitus. The diagnosis of type 2 diabetes by the use of the supplemental questionnaire has been validated in this cohort (17).

Statistical analysis

Person-time of follow up was contributed by each eligible participant from the date of return of the 1984 questionnaire to the date of diagnosis of type 2 diabetes, 1 June 2002, or death from other causes. To reduce within-person variation and best represent long-term usual diet, the cumulative average frequency was calculated from all available questionnaires up to the start of each 2 year follow-up period (18). Participants were divided into quintiles by frequency of intake to avoid assumptions about the shape of the dose-response relationship. Cox proportional hazards models with time-dependent variables were used to adjust for potential confounders, including BMI, family history of diabetes, smoking, postmenopausal hormone use, alcohol intake, and physical activity. We also adjusted for dietary variables that have been related to diabetes in this cohort, including intakes of processed meats, potatoes, nuts, coffee, sodas, and whole grains (19–24). The proportional hazards assumption was tested by modeling the interaction of time with fruit and vegetable intake. To assess the linearity of trends, median values of intake for quintiles were treated as continuous in Cox regression models. Statistical analyses were performed with SAS software (version 9.0; SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS—

The baseline characteristics of the study participants by quintile of total fruit and vegetable intake are presented in Table 1. Women who consumed more fruits and vegetables were older, were less likely to smoke cigarettes, and were more likely to exercise regularly and use hormone replacement therapy than their counterparts who did not consume fruits and vegetables as frequently. The median intake of fruit in this population throughout the follow-up period was 1.08 servings/day, whereas that for vegetables was 3.09 servings/day.

Table 1—

Characteristics of the study population by quintile of total intake of fruit and vegetables in 1984

| Total intake of fruit and vegetables in 1984

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quintile 1 | Quintile 2 | Quintile 3 | Quintile 4 | Quintile 5 | |

| n | 14,573 | 14,408 | 14,337 | 14,118 | 13,910 |

| Median intake fruits and vegetables (servings/day)* | 2.1 | 3.2 | 4.2 | 5.3 | 7.5 |

| Median intake fruit (servings/day)* | 0.5 | 0.9 | 1.2 | 1.7 | 2.5 |

| Median intake vegetables (servings/day) | 1.5 | 2.3 | 3.0 | 3.7 | 5.2 |

| Median intake fruit juices (servings/day) | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.7 |

| Age (years) | 48.5 ± 7.1 | 49.4 ± 7.2 | 50.2 ± 7.1 | 50.8 ± 7.1 | 51.8 ± 7.0 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.5 ± 7.1 | 23.6 ± 7.0 | 23.6 ± 6.9 | 23.7 ± 6.9 | 23.6 ± 7.0 |

| Alcohol (g) | 7.4 ± 12.7 | 7.2 ± 11.6 | 7.1 ± 11.0 | 6.9 ± 10.6 | 6.6 ± 10.5 |

| Physical activity (h/week) | 2.1 ± 2.0 | 2.2 ± 2.1 | 2.4 ± 2.1 | 2.5 ± 2.2 | 2.8 ± 2.3 |

| Current smoker (%) | 34 | 27 | 23 | 20 | 17 |

| Hypertension (%) | 19 | 20 | 19 | 20 | 21 |

| Hypercholesterolemia (%) | 7 | 7 | 7 | 8 | 8 |

| Current use of hormone replacement (%) | 22 | 23 | 24 | 26 | 26 |

| Premenopausal (%) | 47 | 47 | 47 | 46 | 45 |

| Family history of diabetes (%) | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 26 |

| Dietary intake | |||||

| Total energy (kcal) | 1,457 ± 465 | 1,621 ± 474 | 1,744 ± 486 | 1,859 ± 501 | 2,061 ± 537 |

| Carbohydrate (g) | 176 ± 35 | 181 ± 31 | 184 ± 30 | 187 ± 29 | 195 ± 31 |

| Glycemic load (g) | 98 ± 22 | 98 ± 20 | 98 ± 19 | 99 ± 18 | 101 ± 19 |

| Protein (g) | 67 ± 13 | 69 ± 12 | 71 ± 12 | 73 ± 12 | 76 ± 14 |

| Polyunsaturated fat (g) | 11.7 ± 3.3 | 11.9 ± 3.1 | 11.9 ± 3.0 | 11.8 ± 3.0 | 11.6 ± 3.2 |

| Monounsaturated fat (g) | 24.0 ± 4.6 | 23.3 ± 4.1 | 22.7 ± 3.9 | 21.8 ± 3.8 | 20.3 ± 4.0 |

| Saturated fat (g) | 23.9 ± 5.0 | 23.0 ± 4.4 | 22.3 ± 4.2 | 21.5 ± 4.0 | 20.0 ± 4.2 |

| Trans-unsaturated fat (g) | 3.8 ± 1.2 | 3.6 ± 1.1 | 3.4 ± 1.0 | 3.2 ± 1.0 | 2.9 ± 0.9 |

| Cholesterol (mg) | 284 ± 108 | 286 ± 94 | 287 ± 90 | 287 ± 90 | 281 ± 95 |

| Fiber (g) | 12.1 ± 3.2 | 14.4 ± 3.1 | 16.0 ± 3.3 | 17.8 ± 3.6 | 21.3 ± 4.9 |

Data are % categorical or means ± SD of continuous population characteristics adjusted for total energy intake unless otherwise indicated. Total n = 71,346 women.

Neither fruits nor fruit and vegetables include fruit juices.

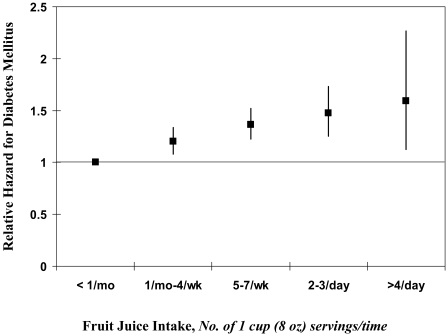

Over the 18 years of follow-up (1,203,994 person-years), we documented 4,529 cases of type 2 diabetes. No association between total fruit and vegetable intake and risk of diabetes was identified in age-adjusted or multivariate- adjusted models (Table 2). Results were similar for intake of total vegetables. Intake of total fruit and green leafy vegetables was inversely associated with development of type 2 diabetes. The multivariate-adjusted hazard ratio (HR) of diabetes by serving frequency for fruit juice is shown in Fig. 1.

Table 2—

Age and multivariate-adjusted HRs (95% CI) for incident type 2 diabetes according to quintile of cumulative averaged intake of fruit and vegetables

| Cumulative averaged intake of fruit and vegetables

|

Ptrend | 3 servings/day and 1 serving/day increase in intake* | Median intake (quintile 1, 5) servings/day† | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quintile 1 | Quintile 2 | Quintile 3 | Quintile 4 | Quintile 5 | ||||

| Vegetables | ||||||||

| n | 845 | 877 | 930 | 976 | 901 | |||

| Person-years | 233,945 | 247,049 | 249,343 | 246,076 | 227,581 | |||

| Age-adjusted | 1.00 | 0.96 (0.88–1.06) | 1.00 (0.91–1.10) | 1.05 (0.96–1.15) | 1.04 (0.95–1.15) | 0.13 | 1.06 (0.98–1.13) | 3.09 (1.61, 5.40) |

| Model 1‡ | 1.00 | 0.98 (0.89–1.08) | 0.98 (0.89–1.08) | 1.03 (0.93–1.13) | 0.98 (0.88–1.09) | 0.92 | 1.00 (0.92–1.08) | |

| Model 2§ | 1.00 | 1.00 (0.91–1.10) | 1.02 (0.93–1.12) | 1.08 (0.98–1.19) | 1.05 (0.94–1.16) | 0.22 | 1.04 (0.97–1.13) | |

| Fruit‖ | ||||||||

| n | 862 | 988 | 948 | 914 | 817 | |||

| Person-years | 237,964 | 249,649 | 247,769 | 241,595 | 227,017 | |||

| Age-adjusted | 1.00 | 1.06 (0.97–1.16) | 1.00 (0.91–1.10) | 0.97 (0.88–1.06) | 0.90 (0.82–0.99) | 0.003 | 0.84 (0.74–0.94) | 1.08 (0.46, 2.64) |

| Model 1‡ | 1.00 | 1.01 (0.92–1.11) | 0.94 (0.86–1.04) | 0.89 (0.81–0.98) | 0.81 (0.73–0.91) | <0.001 | 0.74 (0.65–0.84) | |

| Model 2§ | 1.00 | 1.04 (0.94–1.14) | 0.99 (0.90–1.09) | 0.96 (0.86–1.06) | 0.90 (0.80–1.00) | 0.008 | 0.82 (0.72–0.94) | |

| Fruit and vegetables‖ | ||||||||

| n | 870 | 900 | 945 | 924 | 890 | |||

| Person-years | 237,727 | 248,219 | 247,926 | 244,157 | 225,964 | |||

| Age-adjusted | 1.00 | 0.96 (0.88–1.06) | 0.99 (0.90–1.09) | 0.97 (0.88–1.07) | 1.00 (0.91–1.10) | 0.91 | 1.00 (0.96–1.05) | 4.47 (2.35, 7.66) |

| Model 1‡ | 1.00 | 0.98 (0.89–1.07) | 0.95 (0.87–1.05) | 0.92 (0.84–1.02) | 0.92 (0.82–1.02) | 0.06 | 0.95 (0.90–1.00) | |

| Model 2§ | 1.00 | 1.01 (0.92–1.11) | 1.00 (0.91–1.10) | 0.99 (0.89–1.09) | 1.01 (0.90–1.12) | 0.99 | 0.99 (0.94–1.05) | |

| Fruit juices | ||||||||

| n | 749 | 946 | 1032 | 920 | 882 | |||

| Person-years | 239,408 | 241,268 | 250,260 | 241,633 | 231,425 | |||

| Age-adjusted | 1.00 | 1.21 (1.10–1.34) | 1.28 (1.17–1.41) | 1.17 (1.06–1.28) | 1.17 (1.06–1.29) | 0.10 | 1.05 (0.99–1.12) | 0.54 (0.04, 1.33) |

| Model 1‡ | 1.00 | 1.20 (1.09–1.32) | 1.28 (1.16–1.40) | 1.25 (1.13–1.38) | 1.33 (1.20–1.48) | <0.001 | 1.17 (1.10–1.25) | |

| Model 2§ | 1.00 | 1.21 (1.10–1.33) | 1.29 (1.17–1.42) | 1.25 (1.14–1.38) | 1.35 (1.22–1.50) | <0.001 | 1.18 (1.10–1.26) | |

| Legumes | ||||||||

| n | 825 | 874 | 951 | 968 | 911 | |||

| Person-years | 248,849 | 216,815 | 248,202 | 259,566 | 230,563 | |||

| Age-adjusted | 1.00 | 1.12 (1.02–1.23) | 1.09 (0.99–1.20) | 1.08 (0.99–1.19) | 1.12 (1.02–1.23) | 0.11 | 1.20 (0.96, 1.50) | 0.17 (0.07, 0.45) |

| Model 1‡ | 1.00 | 1.13 (1.03–1.25) | 1.10 (1.00–1.21) | 1.10 (1.00–1.21) | 1.09 (0.99–1.21) | 0.40 | 1.11 (0.87–1.40) | |

| Model 2§ | 1.00 | 1.14 (1.03–1.25) | 1.12 (1.02–1.23) | 1.13 (1.02–1.24) | 1.14 (1.03–1.25) | 0.09 | 1.23 (0.97–1.56) | |

| Green leafy vegetables | ||||||||

| n | 921 | 957 | 995 | 837 | 819 | |||

| Person-years | 223,958 | 239,419 | 256,196 | 241,036 | 243,385 | |||

| Age-adjusted | 1.00 | 0.96 (0.88–1.05) | 0.92 (0.84–1.00) | 0.81 (0.74–0.89) | 0.78 (0.71–0.86) | <0.001 | 0.80 (0.75–0.86) | 0.72 (0.25, 1.48) |

| Model 1‡ | 1.00 | 0.99 (0.90–1.08) | 0.99 (0.90–1.09) | 0.90 (0.82–0.99) | 0.87 (0.78–0.96) | <0.001 | 0.88 (0.82–0.95) | |

| Model 2§ | 1.00 | 1.00 (0.91–1.10) | 1.02 (0.93–1.11) | 0.93 (0.85–1.03) | 0.90 (0.82–1.00) | 0.010 | 0.91 (0.84–0.98) | |

For vegetables, fruit, and fruit and vegetables combined, data for 3 servings/day increase are shown; for all other items, 1 serving/day increase is shown.

Shown is overall median intake for the entire category and, in parentheses, the median intakes for the lowest and highest quintiles, data are in servings/day distribution based on the cumulative average of median values from questionnaires from 1984, 1986, 1990, 1994, and 1998.

Additionally adjusted for BMI, physical activity, family history of diabetes, postmenopausal hormone use, alcohol use, smoking, and total energy intake.

Adjusted for all variables in model 1 and additionally for whole grains, nuts, processed meats, coffee, potatoes, and sugar-sweetened soft drinks.

Neither fruit nor fruit and vegetables include fruit juices.

Figure 1—

Multivariate-adjusted relative hazard of diabetes by category of cumulatively updated fruit juice intake. Values were adjusted for cumulatively updated BMI, physical activity, family history of diabetes, postmenopausal hormone use, alcohol use, smoking, and total energy intake. For an increase of 1 serving/day of fruit juice, the multivariate-adjusted relative risk was 1.18 (95% CI 1.10–1.26; P < 0.0001).

To further investigate the association between fruit juice consumption and development of type 2 diabetes, we subdivided fruit juices into apple, grapefruit, and orange juices and examined them individually in separate models. Among participants consuming >3 cups of apple juice/ month compared with those who consumed <1 cup of apple juice/month, the HR was 1.15 (95% CI 1.08–1.22; Ptrend < 0.001). The corresponding HR for grapefruit juice consumers was 1.14 (1.05–1.23; Ptrend = 0.001). Among participants consuming ≥1 cup of orange juice/day compared with those who consumed <1 cup of orange juice/month, the HR was 1.24 (1.10–1.39; Ptrend < 0.001).

To situate our results for fruit juice intake in the context of results for other beverages, we also examined intake of colas (sugar-sweetened and low-calorie), other carbonated beverages, and fruit punch in relation to hazard of type 2 diabetes. After adjustment for BMI, family history of diabetes, smoking, postmenopausal hormone use, alcohol intake, physical activity, smoking, total energy intake, and consumption of whole grains, nuts, processed meats, coffee, and potatoes, the HRs for an increase of 1 serving/day (95% CI) were 1.08 (1.04–1.12), 1.11 (1.07–1.16), 1.04 (1.00–1.09), and 1.10 (1.06–1.15) for sugar-sweetened cola, low-calorie cola, other carbonated beverages, and fruit punch, respectively.

We also examined whether the relationship between fruit juice intake and diabetes was affected by BMI and physical activity. In multivariate-adjusted models, we identified a modest ordinal interaction that was statistically significant (P < 0.001 for BMI and P = 0.03 for physical activity). Among participants with a BMI ≥25 kg/m2, the HR (95% CI) for those in the highest quintile of fruit juice intake compared with those in the lowest was 1.33 (1.19–1.48); for participants with BMI <25 kg/m2, the corresponding value was 1.60 (1.18–2.16). Among participants who performed ≤1.5 h of physical activity/week, the HR (95% CI) for those in the highest quintile of fruit juice intake compared with those in the lowest was 1.34 (1.18–1.53); for participants who performed >1.5 h of physical activity/day, the corresponding value was 1.42 (1.18–1.73).

CONCLUSIONS—

In this large prospective cohort of middle-aged American women, overall fruit and vegetable intake was not associated with the development of type 2 diabetes. Intake of fruit juices was positively associated with incidence of type 2 diabetes, whereas intake of whole fruits and green leafy vegetables was inversely associated. These associations were independent of known risk factors for type 2 diabetes, including age, BMI, family history, smoking, postmenopausal hormone use, alcohol intake, physical activity, smoking, total energy intake, and consumption of whole grains, nuts, processed meats, coffee, and potatoes. This study is one of the first to prospectively examine fruit juice intake and the risk of type 2 diabetes.

The positive association between fruit juice consumption and diabetes risk may relate to the relative lack of fiber and other phytochemicals, the liquid state, and the high sugar load. The rapid delivery of a large sugar load, without many other components that are a part of whole fruits, may be an important mechanism by which fruit juices could contribute to the development of diabetes. Fructose consumption has also been implicated in the development of many manifestations of the insulin resistance syndrome (25,26). Frequent consumption of fruit juices may contribute to a higher dietary glycemic load, which has been positively associated with diabetes in this cohort (27). Fruit and green leafy vegetables may contribute to a decreased incidence of type 2 diabetes through their low energy density, low glycemic load, and high fiber and micronutrient content (28). In particular, green leafy vegetables may supply magnesium, which has been inversely linked to the development of type 2 diabetes in women (8).

We searched MEDLINE to January 2008 to identify prospective studies of fruit and vegetable intake and risk of type 2 diabetes. In all, we identified six studies that are summarized in Table 3 (5–10). Many of these studies had small sample sizes, combined fruit juice intake with whole fruit intake, and did not include updated measures of dietary intake during the study.

Table 3—

Prospective cohort studies reporting measures of association between intake of fruits and vegetables and diabetes

| Author, year (reference) | Population | n | Age (years), sex | Exposure measure | Adjustments | Follow-up (years) | Case ascertainment | Events | Association (95% CI) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colditz et al., 1992 (5) | U.S. nurses | 84,360 | 34–59, F | 61-item FFQ | Age, BMI, weight change, alcohol energy | 6 | Follow-up questionnaire | 702 diabetes | HR Q5/1 0.76 (0.50–1.16) vegetable intake | Q5/1: ≥2.9 serving/day of vegetables vs. <1.2 |

| Feskens et al., 1995 (6) | Finnish and Dutch | 338 | 70–89, M | Cross-check diet history | Age, cohort, BMI, past BMI, past energy intake | 30 | OGTT | 71 IGT, 26 diabetes | Inverse association of 2-h postload glucose and intake of vegetables and legumes | Multivariate regression predicting 2-h postload glucose |

| Meyer et al., 2000 (7) | Postmenopausal Iowa women | 35,988 | 55–69, F | 127-item FFQ | Age, smoking, total energy, BMI, alcohol, WHR, education, physical activity | 6 | Iowa death register, biennial questionnaire, and NDI | 1,141 diabetes | HR Q5/1 fruit + vegetables 1.05 (0.84–1.31), HR vegetables 1.07 (0.86–1.32), HR fruit 1.14 (0.93–1.39) | Q5/1: >51 servings/week fruit + vegetables vs. <23, Q5/1: >33.5 servings/week vegetable vs. <14, Q 5/1: >19 servings/week fruit vs. <6.25 |

| Ford and Mokdad, 2001 (9) | NHEFS | 9,665 | 25–74, M + F | Single 24-h dietary recall | Age, race, sex, smoking, BMI, alcohol, SBP, lipids, HTN, physical activity | 19 | Follow-up questionnaire, hospital records, death certificates | 1,018 diabetes | HR fruit + vegetable intake 0.73 (0.54–0.98) | ≥5 times/day vs. 0 times/day, no portion size included; also identified a sex interaction |

| Liu et al., 2004 (9) | WHS | 38,018 | ≥45, F | 131-item FFQ | Age, smoking, total energy, alcohol, BMI, physical activity, HTN, hyperlipidemia, FH | 8.8 | Follow-up questionnaire | 1,614 diabetes | HR Q5/1 fruit + vegetables 1.04 (0.87–1.25), HR fruit 0.97 (0.82–1.23), HR vegetables 1.03 (0.86–1.23) | Q5/1: median 10.1 servings/day fruit + vegetables vs. 2.5, Q5/1: median 3.9 servings/day fruit vs. 0.62 |

| Montonen et al., 2005 (10) | Finnish | 4,304 | 40–69, M + F | Diet history | Age, sex, smoking, total energy, BMI, FH, geographic area | 23 | Finnish Social Insurance Institution's national database | 383 diabetes | HR Q4/1 vegetables 0.77 (0.57–1.03), HR green vegetables 0.69 (0.50–0.93), HR fruit 0.82 (0.61–1.11), HR berries 0.63 (0.47–0.85) | Q4/1: >130 g/day vegetables vs. <42, Q4/1: >43 g/day green vegetables vs. <11, Q4/1: >138 g/day fruit vs. <20 |

F, female; FH, family history of diabetes; HTN, hypertension; IGT, impaired glucose tolerance; M, male; NHEFS, First National Health and Nutrition Examination Study Epidemiologic Follow-up Study; OGTT, oral glucose tolerance test; Q, quantile; SBP, systolic blood pressure; WHR, waist-to-hip ratio; WHS, Women's Health Study.

Other investigations have related the consumption of sugar-sweetened or nondiet colas, other sodas, and fruit punches to development of type 2 diabetes (23). In the Nurses' Health Study II cohort, which comprised 91,249 women followed for 8 years from 1991–1999, women consuming at least 1 sugar-sweetened soft drink/day were 1.83 times more likely (95% CI 1.42–2.36; Ptrend < 0.001) to develop type 2 diabetes compared with those who consumed this type of beverage less than once per month, after adjustment for potential confounders. Consumption of fruit punches was also associated with increased diabetes risk (multivariate-adjusted HR 2.00 [95% CI 1.33–3.03]; P = 0.001). In that study, fruit juice consumption was not associated with diabetes risk; however, increased consumption of fruit juices in the first 4 years from baseline was associated with a significantly greater weight gain among women over the course of follow-up (4.03 kg) compared with decreased fruit juice consumption (2.32 kg) during the same period (P < 0.001). Possible reasons for the discrepancy between results in these two cohorts include misclassification of fruit juice intake in the Nurses' Health Study II, which incorporated only two dietary assessments (1991 and 1995). In the present study, five dietary assessments were available (1984, 1986, 1990, 1994, and 1998) to classify fruit juice intake. In addition, the Nurses' Health Study II cohort is younger and over the course of 9 years of follow-up developed only 741 cases of incident type 2 diabetes. In the present study, 18 years of follow-up were available, with 4,529 cases of incident type 2 diabetes.

The primary limitation of our study was the potential for bias due to measurement error. We attempted to reduce measurement error in assessing long-term diet by using the average of all available measurements of diet up to the start of each 2-year follow-up interval (18). In addition, although our results for fruit juice consumption and type 2 diabetes are a relatively new finding, those for green leafy vegetable consumption have been replicated in at least one large study using different dietary assessment methods that should have differently structured measurement errors (10). The possibility of unknown confounding, which cannot be ruled out in any observational study, must also be acknowledged. The FFQ used in this study does not distinguish between canned and fresh fruits, which have different nutrient profiles and may be associated with different food habits. Moreover, the food supply has changed significantly over the past decades, whereas our FFQ has not; nevertheless, the most common foods eaten in the U.S. population are encompassed in our instrument. There may be underestimation of type 2 diabetes by self-report; however, our population is highly educated about medical conditions, so self-report error should be substantially less than that in a general population. Fasting glucose criteria for diabetes were lowered in 1997, possibly contributing to underestimation in this study. Also, it is possible that women may have misreported fruit punches as juices. Fruit punches have been associated with an increased incidence of diabetes in U.S. women (23). Because of the homogeneity of our population, generalizability of these results to women of other race and ethnicity bears further examination.

Our findings of a positive association of fruit juice intake with hazard of diabetes suggest that caution should be observed in replacing some beverages with fruit juices in an effort to provide healthier options. Moreover, the same caution applies to the recommendation that 100% fruit juice be considered a serving of fruit as it is in the present national dietary guidelines (30). In general, the observed associations between fruits and vegetables are weaker than those for cardiovascular disease (31). However, if fruits and vegetables are used to replace refined grains and white potatoes, both of which have been shown to be associated with increased risk of diabetes (20,32), the benefits of regular consumption of fruits and vegetables should be substantial.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by Grants DK58845 and CA87969 from the National Institutes of Health. L.A.B. was supported by a Building Interdisciplinary Research Careers in Women's Health Scholarship (K12 HD43451), which was cofunded by the Office of Research on Women's Health and Office of Dietary Supplements.

The authors thank Drs. Walter C. Willett and JoAnn E. Manson for their help in the preparation of this manuscript.

Published ahead of print at http://care.diabetesjournals.org on 4 April 2008.

L.A.B. had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity and the accuracy of the data analysis.

The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

References

- 1.World Health Organization: Global Burden of Disease, Diabetes Mellitus. Geneva: World Health Org., 2003

- 2.He K, Hu FB, Colditz GA, Manson JE, Willett WC, Liu S: Changes in intake of fruits and vegetables in relation to risk of obesity and weight gain among middle-aged women. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 28:1569–1574, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hung HC, Joshipura KJ, Jiang R, Hu FB, Hunter D, Smith-Warner SA, Colditz GA, Rosner B, Spiegelman D, Willett WC: Fruit and vegetable intake and risk of major chronic disease. J Natl Cancer Inst 96:1577–1584, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Joshipura KJ, Ascherio A, Manson JE, Stampfer MJ, Rimm EB, Speizer FE, Hennekens CH, Spiegelman D, Willett WC: Fruit and vegetable intake in relation to risk of ischemic stroke. JAMA 282:1233–1239, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Colditz GA, Manson JE, Stampfer MJ, Rosner B, Willett WC, Speizer FE: Diet and risk of clinical diabetes in women. Am J Clin Nutr 55:1018–1023, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Feskens EJ, Virtanen SM, Räsänen L, Tuomilehto J, Stengård J, Pekkanen J, Nissinen A, Kromhout D: Dietary factors determining diabetes and impaired glucose tolerance: a 20-year follow-up of the Finnish and Dutch cohorts of the Seven Countries Study. Diabetes Care 18:1104–1112, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meyer KA, Kushi LH, Jacobs DR Jr, Slavin J, Sellers TA, Folsom AR: Carbohydrates, dietary fiber, and incident type 2 diabetes in older women. Am J Clin Nutr 71:921–930, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ford ES, Mokdad AH: Fruit and vegetable consumption and diabetes mellitus incidence among U.S. adults. Prev Med 32:33–39, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu S, Serdula M, Janket SJ, Cook NR, Sesso HD, Willett WC, Manson JE, Buring JE: A prospective study of fruit and vegetable intake and the risk of type 2 diabetes in women. Diabetes Care 27:2993–2996, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Montonen J, Jarvinen R, Heliovaara M, Reunanen A, Aromaa A, Knekt P: Food consumption and the incidence of type II diabetes mellitus. Eur J Clin Nutr 59:441–448, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kris-Etherton PM, Hecker KD, Bonanome A, Coval SM, Binkoski AE, Hilpert KF, Griel AE, Etherton TD: Bioactive compounds in foods: their role in the prevention of cardiovascular disease and cancer. Am J Med 113 (Suppl. 9B):71S–88S, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Nurse's Health Study Semi-Quantitative Food Frequency Questionnaire [article online]. Available from http://www.channing.harvard.edu/nhs/questionnaires/pdfs/NHSI/1984.pdf. Accessed on 25 February 2008

- 13.Steinmetz KA, Potter JD, Folsom AR: Vegetables, fruit, and lung cancer in the Iowa Women's Health Study. Cancer Res 53:536–543, 1993 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Willett WC, Sampson L, Stampfer MJ, Rosner B, Bain C, Witschi J, Hennekens CH, Speizer FE: Reproducibility and validity of a semiquantitative food frequency questionnaire. Am J Epidemiol 122:51–65, 1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Salvini S, Hunter DJ, Sampson L, Stampfer MJ, Colditz GA, Rosner B, Willett WC: Food-based validation of a dietary questionnaire: the effects of week-to-week variation in food consumption. Int J Epidemiol 18:858–867, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Classification and diagnosis of diabetes mellitus and other categories of glucose intolerance: National Diabetes Data Group. Diabetes 28:1039–1057, 1979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Manson JE, Rimm EB, Stampfer MJ, Colditz GA, Willett WC, Krolewski AS, Rosner B, Hennekens CH, Speizer FE: Physical activity and incidence of non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus in women. Lancet 338:774–778, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hu FB, Stampfer MJ, Rimm E, Ascherio A, Rosner BA, Spiegelman D, Willett WC: Dietary fat and coronary heart disease: a comparison of approaches for adjusting for total energy intake and modeling repeated dietary measurements. Am J Epidemiol 149:531–540, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fung TT, Schulze M, Manson JE, Willett WC, Hu FB: Dietary patterns, meat intake, and the risk of type 2 diabetes in women. Arch Intern Med 164:2235–2240, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Halton TL, Willett WC, Liu S, Manson JE, Stampfer MJ, Hu FB: Potato and french fry consumption and risk of type 2 diabetes in women. Am J Clin Nutr 83:284–290, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jiang R, Manson JE, Stampfer MJ, Liu S, Willett WC, Hu FB: Nut and peanut butter consumption and risk of type 2 diabetes in women. JAMA 288:2554–2560, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Salazar-Martinez E, Willett WC, Ascherio A, Manson JE, Leitzmann MF, Stampfer MJ, Hu FB: Coffee consumption and risk for type 2 diabetes mellitus. Ann Intern Med 140:1–8, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schulze MB, Manson JE, Ludwig DS, Colditz GA, Stampfer MJ, Willett WC, Hu FB: Sugar-sweetened beverages, weight gain, and incidence of type 2 diabetes in young and middle-aged women. JAMA 292:927–934, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.de Munter JS, Hu FB, Spiegelman D, Franz M, van Dam RM: Whole grain, bran, and germ intake and risk of type 2 diabetes: a prospective cohort study and systematic review. PLoS Med 8:e261, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Elliott SS, Keim NL, Stern JS, Teff K, Havel PJ: Fructose, weight gain, and the insulin resistance syndrome. Am J Clin Nutr 76:911–922, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Teff KL, Elliott SS, Tschöp M, Kieffer TJ, Rader D, Heiman M, Townsend RR, Keim NL, D'Alessio D, Havel PJ: Dietary fructose reduces circulating insulin and leptin, attenuates postprandial suppression of ghrelin, and increases triglycerides in women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 89:2963–2972, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Salmeron J, Manson JE, Stampfer MJ, Colditz GA, Wing AL, Willett WC: Dietary fiber glycemic load, and risk of non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus in women. JAMA 277:472–477, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bazzano LA, He J, Ogden LG, Loria CM, Vupputuri S, Myers L, Whelton PK: Fruit and vegetable intake and risk of cardiovascular disease in US adults: the First National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey Epidemiologic Follow-up Study. Am J Clin Nutr 76:93–99, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and U.S. Department of Agriculture: Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2005. 6th ed. Washington, DC, U.S. Govt. Printing Office, 2005

- 31.Hu FB, Willett WC: Optimal diets for prevention of coronary heart disease. JAMA 288:2569–2578, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hu FB, Manson JE, Stampfer MJ, Colditz G, Liu S, Solomon CG, Willett WC: Diet, lifestyle, and the risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus in women. N Engl J Med 345:790–797, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]