Abstract

OBJECTIVE—To develop and assess the feasibility of an early preconception counseling program for adolescents called READY-Girls (Reproductive-health Education and Awareness of Diabetes in Youth for Girls).

RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS—A total of 53 adolescent females with type 1 diabetes between 16 and 19.9 years of age were randomized into groups receiving a CD-ROM, a book, or standard care (control) and given one comprehensive session. Outcomes were assessed at baseline, immediately after, and at 3 months.

RESULTS—Teens who received the CD and those who received the book demonstrated significant (P ≤ 0.05) sustained improvement (over 3 months) in knowledge, perceived benefits of both receiving preconception counseling and using effective family planning, and perceived more support with reproductive health issues.

CONCLUSIONS—Clinical feasibility of the program was demonstrated. Both the CD and the book appeared to be efficacious formats for the short term. Future studies should examine repeated boosters of a CD and a book, which are not meant to replace but rather to reinforce and supplement health professional education.

Risks of reproductive complications can be significantly reduced through preconception counseling (PC) (1–3). Despite recommendations by the American Diabetes Association that all women of child-bearing potential receive PC (4), most diabetic women do not, and two-thirds continue to have unplanned pregnancies (5–8). In a previous study, we found that adolescent diabetic females reported unsafe sexual practices and were unaware of the risks of diabetes and pregnancy and of the availability of PC (9). This study developed a fundamental PC program called READY-Girl (Reproductive-health Education and Awareness of Diabetes in Youth for Girls) specifically tailored for diabetic adolescents and explored the clinical feasibility of short-term (3 months) program efficacy as well as the most effective form of delivery: CD-ROM or book.

RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS

The educational materials for READY-Girls (10) are a self-instructional, developmentally appropriate, evidence-based CD and book (4–9,11). Content was validated through resource identification, formal consensus of experts (12,13), and a focus group of diabetic teens for content, language, and presentation (12).

Embedded within the STAR (stop-think-act-reflect) decision-making framework (13,14) and the Expanded Health Belief Model (EHBM) (15–19,20,21), READY-Girls presents the effects of diabetes on reproductive health/puberty/sexuality/pregnancy and the benefits of PC and offers practice for the development of skills involving decision making/communication.

In a randomized, controlled, repeated-measures feasibility study, subjects were randomized into one of three protocols: CD (n = 17), book (n = 16), or standard care (control) (n = 20). Both intervention groups (CD or book) received one comprehensive session of the program before routine diabetes clinic visits. Subjects were seen only at their routine visits. Process evaluation included timing, effort, ease of use, and satisfaction. Outcome measures evaluated reproductive health and PC knowledge, beliefs (EHBM dimensions: susceptibility, severity, benefits, barriers, self-efficacy, motivational cues, and social support), intention and behaviors (of seeking PC and using effective family planning), and metabolic control. Each dimension was a composite score (higher scores = greater levels of the construct). Outcomes were assessed at baseline, immediately postintervention (post-test 1), and at 3-month follow-up (post-test 2) by paper-and-pencil self-administered questionnaires (Cronbach's α = 0.65–0.83) based on a standard validated interview schedule (22–23). Data were analyzed using descriptive statistics, group comparative analyses, and repeated-measures mixed-modeling methods (24). Post hoc comparisons explored group main effects and group-by-time interactions.

Of a possible 60 females with type 1 diabetes between 16 and 19.9 years of age (mean 17.4) from a diabetes clinic, 53 self-selected to participate. Their mean duration of illness was 9.9 years, 64% were from middle-income families, 4.4% were African American, and 32% were sexually active. Consent was obtained from teens aged >18 years of age or consent/assent from parents and teens aged <18 years.

RESULTS

Both the CD and book took <1 h to review (average time: CD 47.0 ± 15 min vs. book 34.3 ± 8.4 min). Both were rated (94–100%) as having helpful, easy-to-understand information.

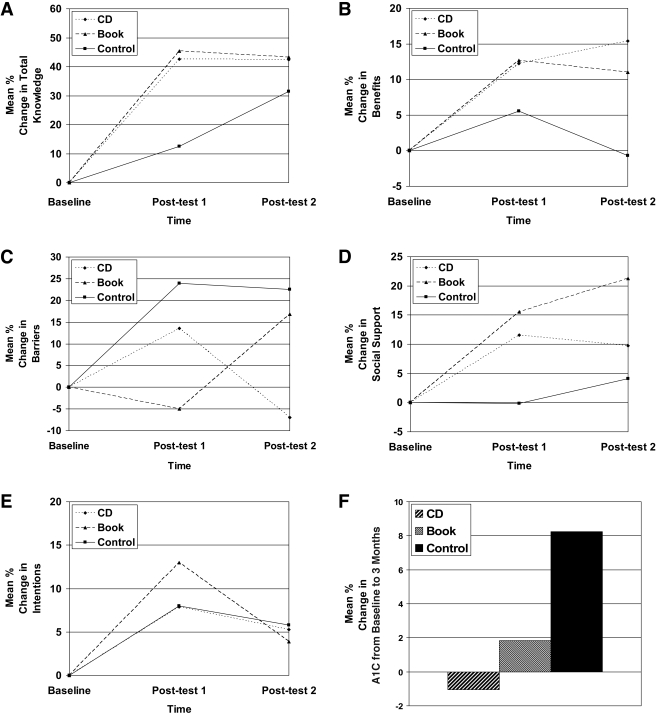

Results for knowledge, beliefs (benefits and barriers), social support, intentions, and metabolic control (A1C) are illustrated in Fig. 1. From baseline to immediately postintervention (post-test 1), compared with control subjects, teens that received the program significantly improved in knowledge (CD 42.7%, P < 0.001; book 45.3%, P < 0.001; control 12.6%, P = 0.38) and sustained effects at the 3-month follow-up (post-test 2) (CD P = 0.96; book P = 0.71). Compared with baseline, teens in the control group had increased their knowledge scores at 3 months (19.0%, P = 0.004). A significant time-by-group interaction was found for knowledge [F (2,40.1) = 3.77, P = 0.032].

Figure 1—

Group response profiles for outcome variables expressed as percent change from baseline values to follow-up post-test values. A: Total knowledge (diabetes pregnancy, contraception, sexuality, and family planning), a summation of 25 dichotomous items (correct = 1, incorrect = 0, % correct). B: Perceived benefits of seeking PC and using family planning, a summation of five Likert-type items (possible range = 5–25). C: Perceived barriers to seeking PC and using family planning, a summation score of five Likert-type items (possible range = 5–25). D: Perceived availability of social support (emotional, informational, and instrumental) with PC and family planning, a summation of eight Likert-type items (possible range = 8–40). E: Intention to seek PC and use effective family planning, a summation of three items (1 = unlikely through 7 = likely; possible range = 3–21). F: A1C (metabolic control) measured by the home Accu-Base HbA1c Sample Collection Kit. Blood fingerstick assays were analyzed in Vanderbilt Pathology Lab Services, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, using a high-performance liquid chromatography analyzer (ion-exchange method) (Bio-Rad Diamat HPLC; Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). The reference range for the Diamat HPLC was 4.2–5.8%. Baseline = pretest; post-test 1 = immediate postintervention; and post-test 2 = 3-month follow-up. Three-month analyses were conducted on completed longitudinal data from 47 subjects (16 [34%] CD, 16 [34%] book, and 15 [32%] control) controlling for sexual activity and age as covariates.

There were significant group-by-time effects for beliefs (benefits and barriers) [benefits F (2,40.1) = 3.48, P = 0.040; barriers F (2,40) = 4.82, P = 0.013]. From baseline to post-test 1, teens who received the program significantly improved in benefits (CD 12.3%, P = 0.05; book 12.7%, P = 0.04; control, P = 0.44). Effects were sustained at post-test 2 for those receiving the program (CD P = 0.19; book P = 0.49) and were significantly decreased for control subjects (−6.2%, P = 0.03). With regard to perceived barriers to seeking PC and using family planning, the only significant change from baseline to post-test 1 was in control subjects (24.0%, P = 0.02). At 3 months, those who received the CD had significantly decreased (−20.5%, P = 0.04) perceptions of barriers, those that received the book had significantly increased (21.8% P = 0.03) perceptions of barriers, and control subjects had no significant change (P = 0.90). No significant group-by-time or group effects were observed for susceptibility, severity, or self-efficacy.

Social support had significant group effects [F (2,39.4) = 3.37, P = 0.045]. Both intervention groups showed a significant increase in social support from baseline to immediate post-test 1 (CD 11.5%, P = 0.007; book 15.6%, P < 0.001; control, P = 0.98), with effects sustained at post-test 2.

Intention to seek PC and use effective family planning had a significant time effect [F (1,37) = 5.75, P = 0.022] from baseline to post-test 1. Only those who received the book showed a significant decrease from post-test 1 to post-test 2 (−13.0%, P = 0.02); those who received the CD and control subjects sustained their modest increases. Actual behaviors (seeking PC and using effective family planning) had no significant group-by-time effect.

A1C had no significant group differences from baseline to 3-month follow-up (P = 0.134). However, those who received the CD had an average decrease of −1% compared with those who received the book (average increase 2%) and control subjects (average increase 8%).

CONCLUSIONS

Program evaluation (25) was completed over a 3-month follow-up. Clinical feasibility of the READY-Girl's program was demonstrated, and both interventions (CD and book) appeared to be efficacious formats.

Compared with control subjects, teens who received the program improved in knowledge, perceived benefits of receiving PC and using effective family planning, and perceived more support regarding reproductive health issues, preventing an unplanned pregnancy, and seeking PC. These findings are in accordance with the EHBM (20,21).

The CD and control groups identified greater barriers. The CD group had diminished barriers at 3 months, perhaps because the CD had an interactive individualized problem-solving exercise. Intention to use effective family planning and to seek PC increased in all three groups. Actual behaviors had no significant group-by-time effect, perhaps because of the short time frame of 3 months.

Although there was no significant group effect, the percent change in A1C from baseline to 3 months appears to be clinically meaningful; the A1C of the CD group decreased by −1% (indicating improved control), while the A1C of the control group had a percent change of 8%. Future studies should include younger, larger, more diverse sample sizes, and longer-term outcomes. Beginning at puberty, the intervention should be targeted to teens and include their parents, and the CD-ROM and book could be used sequentially, with the information repeated for reinforcement. READY-Girls appears to be an efficacious early intervention program for teens. READY-Girls is not meant to replace but rather to supplement professional health education (12). Both the CD-ROM and book (10) are designed to be easily integrated into clinical settings. Similar programs have been successful for other health behaviors (12,26–28). Programs such as READY-Girls could potentially set new standards of practice and be an integral part of diabetic adolescent education to empower teens in making informed decisions regarding their reproductive health (12).

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the American Diabetes Association Clinical Research Award (1999–2003), the general clinical research center of Children's Hospital of Pittsburgh (grant M01 RR00084), and the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Nursing Research Center for Research in Chronic Disorders (grant P30 NR03924).

Parts of this study were presented in abstract form at the 61st annual meeting of the American Diabetes Association, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 22–26 June 2001; and at the 62nd annual meeting of the American Diabetes Association, San Francisco, California, 14–18 June 2002.

We acknowledge the Center for Instructional Development and Distance Education at the University of Pittsburgh, dbaza Inc. Production Company, Barbara Anderson, Millecent Ball, Janet Bell, Jean Betschart Roemer, Beth Cohen, Mary Ann Cwynar, Tracy Dean-McElhinny, Richard Engberg, Melanie Gold, Bill Herman, Scott Jacober, Nancy Janz, Kristin Kolence, Danielle Lockhart, Joan Mansfield, Margaret Marshall, Cindy McQuaide, DeEta Metz, Pamela Murray, Gale Podabinski, Jamie Reddinger, Sergey Sirotinin, Mark Soroka, Sandy Hughes Stewart, Linda Trail, Shiaw-Ling Wang, and Neil White for their efforts.

Published ahead of print at http://care.diabetesjournals.org on 14 April 2008.

The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cohen M: Pregnancy in women with diabetes. J Women's Health 1:81–87, 1992 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Greene M, Hare J, Cloherty J, Benacerraf B, Soeldner J: First trimester hemoglobin A1 and risk for major malformation and spontaneous abortion in diabetic pregnancy. Diabetes Spectrum 3:161–167, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mills J, Knopp R, Simpson J, Jovanovic-Peterson L, Metzger B, Holmes L, et al: Lack of relation of increased malformation rates in infants of diabetic mothers to glycemic control during organogenesis. N Engl J Med 318:671–676, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.American Diabetes Association: Preconception care of women with diabetes (Position Statement). Diabetes Care 27(Suppl. 1):S76–S78, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kjaer K, Hagen C, Sand E, Eshoj O: Contraception in women with IDDM. Diabetes Care 15:1585–1590, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kitzmiller JL, Gavin LA, Gin GD, Jovanovic-Peterson L, Main EK, Aigrang WD: Preconception care of diabetes: glycemic control prevents congenital anomalies. J Am Med Assoc 13:731–736, 1991 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.St James P, Younger M, Hamilton B, Waisbrem S: Unplanned pregnancies in young women with diabetes. Diabetes Care 16:1572–1578, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Willhoite M, et al: The impact of preconception counseling on pregnancy outcomes: the experience of the Maine Diabetes in Pregnancy Program. Diabetes Care 16:450–455, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Charron-Prochownik D, Sereika SM, Becker D, et al: Reproductive health beliefs and behaviors in teens with diabetes: application of the expanded health belief model. Pediatric Diabetes 2:30–39, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Charron-Prochownik D: Reproductive-Health Awareness for Teenage Women With Diabetes: What Teens Want to Know About Sexuality, Pregnancy, and Diabetes. Alexandria, VA, American Diabetes Association, 2003

- 11.Marshall M, Jennings V, Cachan J: Reproductive health awareness: an integrated approach to obtaining a high quality of health. Adv Contracept 13:313–318, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Charron-Prochownik D, Ferons Hannan M, Sereika S, Becker D, Rodgers-Fischl A: How to develop CD-ROMs for diabetes education: exemplar “Reproductive-health Education and Awareness of diabetes in Youth for Girls” (READY-Girls). Diabetes Spectrum 19:110–115, 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anderson B, Burkhart M, Charron-Prohownik D: Making Choices: Teenagers and Diabetes. Ann Arbor, MI, University of Michigan Press, 1986

- 14.Meichenbaum D: Coping with Stress. Toronto, Ontario, John Wiley & Sons, 1983

- 15.Conner M, Norman P: The role of social cognition in health behaviors. In Predicting Health Behavior: Research and Practice with Social Cognition Models. Conner M, Norman P, Eds. Buckingham, Open University Press, 1996, p. 23–61

- 16.Maiman L, Becker M: The health belief model: origins and correlates in psychological theory. In The Health Belief Model and Personal Health Behaviors. Becker MH, Ed. Thorofare NJ, Charles B. Slack, Inc, 1974, p. 336–353

- 17.Janz NK, Champion VL, Strecher VJ: The Health Belief Model. In Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research, and Practice. Glanz K, Rimer BK, Lewis FM, Eds. San Francisco, Jossey-Bass Publishers, 2002, p. 41–59

- 18.Strecher V, Rosenstock I: The health belief model. In Health Behavior & Health Education. San Francisco, Jossey-Bass, 1997, p. 41–59

- 19.Wang, S-L, Charron-Prochownik D, Sereika S, Siminerio L, Kim Y: Comparing three theories in predicting reproductive health behavioral intention in adolescent women with diabetes. Pediatric Diabetes 7:108–115, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rosenstock I, Strecher V, Becker M: Social learning theory and the health belief model. Health Educ Q 15:175–183, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Burns AC: The expanded health belief model as a basis for enlightened preventive health care practice and research. J Health Care Marketing 12:32–45, 1992 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Charron-Prochownik D, Wang, S-L, Sereika S, Kim Y, Janz N: A theory-based reproductive health and diabetes instrument. Am J Health Behavior 30:208–220, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Janz NK, Herman WH, Becker M, Charron-Prochownik D, Shayna VL, Lesnick TG, Jacober SJ, Fachnie JD, Kruger DF, Sanfield JA, et al: Diabetes and pregnancy: factors associated with seeking preconception care. Diabetes Care 18:157–165, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cohen J: Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. 2nd ed. Hillsdale NJ, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc., 1988

- 25.Sussman S: Program Development for Health Behavior Research & Practice. Thousand Oaks, CA, Sage Publications, Inc., 2001

- 26.Khalili A, Shashaani L: The effectiveness of computer applications: a meta-analysis. J Research Comput Educ 27:48–61, 1994 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miller WC, et al: Successful weight loss in a self taught, self administered program. Int J Sports Med 14:401–440, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.King DK, Bull SS, Christiansen S, Nelson C, Strycker LA, Toobert D, Glasgow RE: Developing and using interactive health CD-ROMs as a complement to primary care: lessons from two research studies. Diabetes Spectrum 17:234–242, 2004 [Google Scholar]