Abstract

The structural basis for the photochromism in the fluorescent protein Dronpa is poorly understood, because the crystal structures of the bright state of the protein did not provide an answer to the mechanism of the photochromism, and structural determination of the dark state has been elusive. We performed NMR analyses of Dronpa in solution at ambient temperatures to find structural flexibility of the protein in the dark state. Light-induced changes in interactions between the chromophore and β-barrel are responsible for switching between the two states. In the bright state, the apex of the chromophore tethers to the barrel by a hydrogen bond, and an imidazole ring protruding from the barrel stabilizes the plane of the chromophore. These interactions are disrupted by strong illumination with blue light, and the chromophore, together with a part of the β-barrel, becomes flexible, leading to a nonradiative decay process.

Keywords: crystal structure, NMR, photochromism

Photochromism is defined as the reversible transformation of a single chemical species between two states having different absorption spectra induced by photoirradiation (1). Most of photochromic substances are organic compounds, including diarylethenes (2) and spiropyran (3). Dronpa is a photochromic fluorescent protein engineered from a coral protein (4). Whereas Dronpa normally absorbs at 503 nm and emits green fluorescence with a high fluorescence quantum yield (φFL = 0.85), strong irradiation at 488 nm can convert this protein to a nonfluorescent state that absorbs at 390 nm (dark state, denoted by DronpaD). The protein can then be switched back to the original emissive state (bright state, denoted by DronpaB) with minimal irradiation at 405 nm. Because of its reliable photochromic properties, Dronpa can be used to record, erase, or read information in a nondestructive manner (4).

Reversible transformation in photochromic systems has been studied in organic compounds (1). This process comprises hydrogen transfer, dimerization, cyclization, ring opening, and isomerization. It is unknown whether the photochromism exhibited by Dronpa employs similar mechanisms or a previously uncharacterized one that utilizes the unique structure of fluorescent proteins. Comparing the structures of DronpaB and DronpaD is essential to understand the mechanism of photochromism in Dronpa. Although three groups (5–7) have reported that the crystal structure of DronpaB is similar to other fluorescent proteins, there is less structural information for DronpaD. Recently, cis-trans photoisomerization of the chromophore has been proposed as the structural basis of the Dronpa photochromism (8). However, trans configuration alone does not provide a photochemical explanation for nonfluorescence. In x-ray crystallographic studies, protein crystals are commonly frozen to 80 K to reduce radiation damage and thermal vibrations to lower conformational disorder and improve the quality of the model. However, in our initial crystallographic studies, we observed that our crystals of Dronpa were resistant to phototransformation at 80 K but not at room temperature (298 K). Thus, we used NMR analyses near room temperature to explore the dynamic structure of DronpaD unattainable by crystallographic methods at 80 K.

Results

Photoresistance of Dronpa at Low Temperatures.

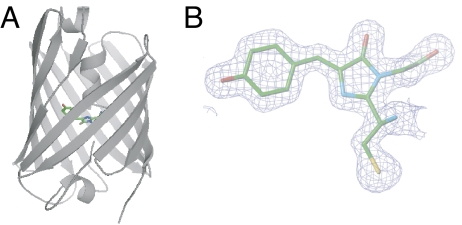

We also determined the DronpaB crystal structure at 1.75-Å resolution; the overall and chromophore structures are shown in Fig. 1 A and B, respectively. In an attempt to determine the crystal structure of DronpaD, we performed photoirradiation experiments with these crystals using the 514.5-nm line of an argon ion laser. Interestingly, whereas the 514.5-nm light dimmed the crystals efficiently at 298 K, the crystals were resistant to transformation at 80 K on the x-ray beam line for crystallography [supporting information (SI) Fig. S1]. The photoresistance of Dronpa at low temperatures was also verified in solution with experiments by using the Joule–Thompson apparatus (R.A., H.M., and A.M., unpublished results).

Fig. 1.

Crystal structure of DronpaB (PDB ID 2Z1O). (A) Overall structure is shown in the cartoon with the chromophore (stick format). (B) A 2Fo-Fc electron density map of the chromophore contoured at 1.2σ. A space group of the crystal was P212121. We also solved structures of DronpaB with space groups of P21 and P21212 and obtained substantially the same results (PDB IDs 2Z6Y and 2Z6Z).

Flexibility Found in the β-Barrel of DronpaD.

To explore a possibly dynamic structure of DronpaD, we performed solution NMR analyses using both DronpaB and DronpaD. The difficulty of these experiments was compounded by the fact that DronpaD is not stable for days; DronpaD converts to DronpaB gradually even in the dark (4). During ≈3 days of NMR measurements, we maintained DronpaD by continuous illumination at 514.5 nm by means of an optical fiber connected to a 150-mW argon ion laser. The protein sample that had experienced the long-term laser illumination displayed a full dark-to-bright conversion upon illumination at 390 nm (Fig. S2).

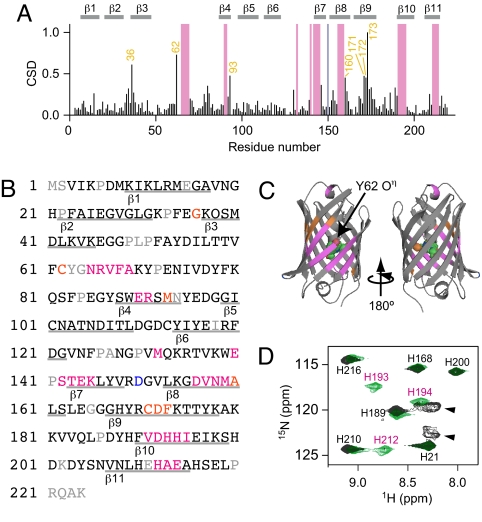

Dronpa was uniformly labeled with 13C and 15N, and NMR spectra were acquired for assignment of 13Cα, 13Cβ, 15N, and 1HN resonances of DronpaB and subsequently of DronpaD (Fig. S3). The backbone assignment identified 93% and 83% of the residues of Dronpa in the DronpaB and DronpaD spectra, respectively; all prolines and the chromophore Tyr and Gly were excluded from the calculation, because they have no protons on their backbone nitrogens. Twenty-five peaks assigned for DronpaB were not assigned for DronpaD because of extensive linewidth broadening. Conversely, one peak assigned for DronpaD is missing in the DronpaB. The residues corresponding to the DronpaB- and DronpaD-specific peaks are positioned as magenta and blue bars, respectively, in the chemical shift difference (CSD) plot (9) (Fig. 2A). Seven residues show highly different chemical shifts between the DronpaB and DronpaD spectra. These residues are numbered in orange in the CSD plot (Fig. 2A). Most of the residues associated with these differential peaks are located on the β-strands near the chromophore hydroxyphenyl moiety, as painted in magenta, blue, and orange on the crystal structure of DronpaB (Fig. 2 B and C). It was speculated that these colored regions in DronpaD had a deviated structure from the DronpaB β-barrel. In particular, the magenta region comprises 25 aa that were not assignable in DronpaD. We conclude that the magenta region in DronpaD takes a polymorphic and flexible structure. This is consistent with the fact that we could not obtain the Dronpa dark state at 80 K, a temperature at which molecular motion is highly restricted (Fig. S1).

Fig. 2.

β-Barrel structures of DronpaB and DronpaD analyzed by NMR spectroscopy. (A) Normalized weighted CSD between DronpaB and DronpaD. CSD values >0.4 are marked with residue numbers in orange. Residues assigned specifically in DronpaB and DronpaD are highlighted with magenta and blue bars, respectively. (B) The Dronpa sequence in which the differential residues are indicated in the same color. (C) Mapping of the differential residues with magenta, blue, and orange on the DronpaB crystal structure. (D) The 1H-15N HSQC spectra of His- 13C6,15N3-labeled DronpaB (green) and DronpaD (black). Peaks are marked with amino acids (single letter code) and residue numbers. DronpaB-specific peaks are marked in magenta. DronpaD-specific broad peaks are indicated by arrowhead.

To characterize the DronpaD-specific structure of the β-strands, we analyzed histidine (His)-13C6,15N3-labeled Dronpa. Among the nine His residues in Dronpa, His-193, His-194, and His-212 reside in the differential regions. There were differences in the 1H-15N heteronuclear sequential quantum correlation (HSQC) spectra between DronpaB and DronpaD for only these three His residues (Fig. 2D). In the DronpaB spectrum, each of the nine His residues was assigned as a sharp peak. In the DronpaD spectrum, by contrast, the three sharp peaks corresponding to His-193, His-194, and His-212 were replaced by two broad peaks. This broadening of peaks is consistent with the greater flexibility of the β-strands containing H193, H194, and H212 in DronpaD.

Chromophore Structures of DronpaB and DronpaD.

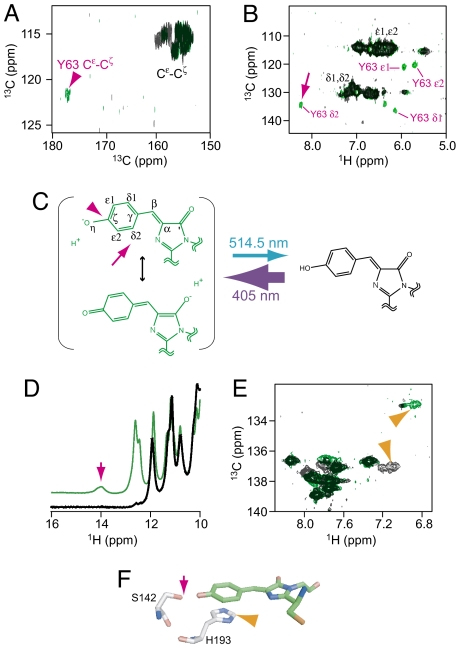

Crystallographic models propose that DronpaB has a rigid cis/coplanar chromophore (Fig. 1B). What structural changes near the chromophore would be associated with the structural flexibility we observe in the β-barrel of DronpaD? In most fluorescent proteins, the hydroxyphenyl moiety of a tyrosine residue within the chromophore-forming tripeptide is critical for fluorescence (10). This tyrosine is located at position 63 in Dronpa. To examine Tyr-63-related structures in DronpaB and DronpaD, we labeled the protein with Tyr-13C9 and used a cryogenic TCI probe for direct detection of 13C resonances at high sensitivity. A large downfield shift was observed for Cζ of Tyr-63 to 177.0 ppm in the 13C-13C NOESY spectrum (11) for DronpaB (Fig. 3A, magenta arrowhead). This indicates deprotonation of the hydroxyphenyl moiety as a rise in electron density by deprotonation increases electric shield. In contrast, no downfield shift was observed for Cζ in the spectrum for DronpaD (Fig. 3A). Therefore, we conclude that the hydroxyphenyl moiety is deprotonated in DronpaB and protonated in DronpaD (Fig. 3C, magenta arrowhead). The protonation/deprotonation equilibrium is consistent with NMR-based pH titration data (12, 13).

Fig. 3.

Chromophore structures of DronpaB and DronpaD revealed by NMR analyses. (A) Expanded 13C-13C NOESY spectra of Tyr-13C9-labeled DronpaB (green) and DronpaD (black). Full 13C-13C NOESY spectrum of Tyr-13C9-labeled DronpaB is shown in Fig. S5. A downfield shifted peak is assigned to Tyr-63 Cε-Cζ of DronpaB (magenta arrowhead). (B) The 1H-13C HSQC spectra of Tyr-13C9-labeled DronpaB (green) and DronpaD (black). Peaks assigned for Cδ1-Hδ1, Cδ2-Hδ2, Cε1-Hε1, and Cε2-Hε2 of DronpaB Tyr-63 are colored magenta. The Cδ2-Hδ2 correlation is evidenced by the downfield shift of the 1H chemical shift (magenta arrow). (C) Light-dependent conversion between DronpaB and DronpaD. Magenta arrowhead and arrow indicate Cζ, and Cδ2-Hδ2, respectively. (D) Expanded 1H NMR spectra acquired at −1.6°C with U-13C,15N-labeled DronpaB (green) and DronpaD (black). Magenta arrow indicates a peak tentatively assignable to 1H on hydroxyl group of Ser-142, which is detectable only in DronpaB. (E) Expanded 1H-13C HSQC spectra of His-13C6,15N3-labeled DronpaB (green) and DronpaD (black). Peaks tentatively assignable to Cε1 -Hε1 of His-193 are indicated by orange arrowhead. (F) Relative position of the chromophore, Ser-142, and His-193. Hydroxyl group of Ser-142 (magenta arrow) and Cε1 of His-193 (orange arrowhead) are indicated.

The 1H-13C HSQC spectra obtained from the Tyr-13C9-labeled Dronpa also provided important information about the conformation of the chromophore. In the spectrum for DronpaB, Tyr-63 Hδ2 displayed a substantial downfield shift that was apparently caused by a ring current effect of the imidazolinone ring (Fig. 3B, magenta arrow). This proton–ring interaction reveals the cis coplanar conformation of the chromophore (Fig. 3C, magenta arrow) also observed in the DronpaB crystal structure (Fig. 1A). The downfield shift of Tyr-63 Hδ2 was never observed for DronpaD (Fig. 3B), demonstrating that the Hδ2 is not on the same plane as the imidazolinone ring in the dark state.

Light-Induced Regulation of Interaction Between the β-Barrel and Chromophore.

We propose that the hydroxyphenyl moiety of the chromophore and the β-strands near the moiety are fixed in DronpaB but flexible in DronpaD. How is the rigidity and flexibility controlled? As the chromophore Oη and the hydroxyl group of Ser-142 face each other in close proximity in the DronpaB crystal (2.73 Å, Fig. 3F; see also Fig. S4), this interaction should be critical for tethering the chromophore to this β-barrel. In DronpaB, the deprotonated Oη is negatively charged and forms a hydrogen bond with the Ser-142 hydroxyl hydrogen (Fig. S4). In contrast, in DronpaD, the protonated Oη would not form this hydrogen bond. To determine whether this hydrogen bond exists exclusively in DronpaB, we examined 1H NMR at −1.6°C because the proton resonance of a serine hydroxyl group can generally be detected at ≈14 ppm only when the group forms a hydrogen bond (14). A peak for the proton assigned to the Ser-142 hydroxyl group at 14.0 ppm was present only in the spectrum for DronpaB (Fig. 3D). We confirmed the requirement of this hydrogen bond for the bright fluorescence of Dronpa by mutating this serine residue. Replacement of Ser-142 with Ala, Cys, Asp, or Gly generated DronpaD-like variants that absorbed light maximally at 390 nm (data not shown). Similar results were obtained by replacing Tyr-63 with Phe (data not shown).

As expected from the results of Fig. 2D, His-193, His-194, and His-212 may be in the flexible part of the β-strands in DronpaD. In the 1H-13C HSQC spectrum of His-13C6,15N3-labeled Dronpa, there was an upfield shift of His-193 Cε1 in DronpaB (Fig. 3E), consistent with a ring current effect of the chromophore phenyl moiety. Thus, the His-193 imidazole likely forms a stacking interaction with the chromophore in DronpaB (Fig. 3F). Replacement of His-193 with Thr also prevented fixation of the chromophore and the resultant His193Thr mutant was nonfluorescent regardless of the protonation/deprotonation of the chromophore Oη (data not shown).

Quaternary Structure and Prevention of Conversion into DronpaD.

Substantial photochromism was originally identified in the course of mutagenesis studies that aimed at monomerizing 22G, a coral fluorescent protein that forms an obligate tetrameric complex. Like most other wild-type GFP-like proteins, 22G forms a tight tetrameric complex and shows no photochromism. Six mutations on 22G, namely, Ile102Asn, Phe114Tyr, Leu162Ser, Arg194His, Asn205Ser, and Gly218Glu on 22G have led to creation of the monomeric and photochromic fluorescent protein, Dronpa. It was thus hypothesized that the light-regulated structural flexibility observed in Dronpa was affected by oligomerization of the β-barrel structure.

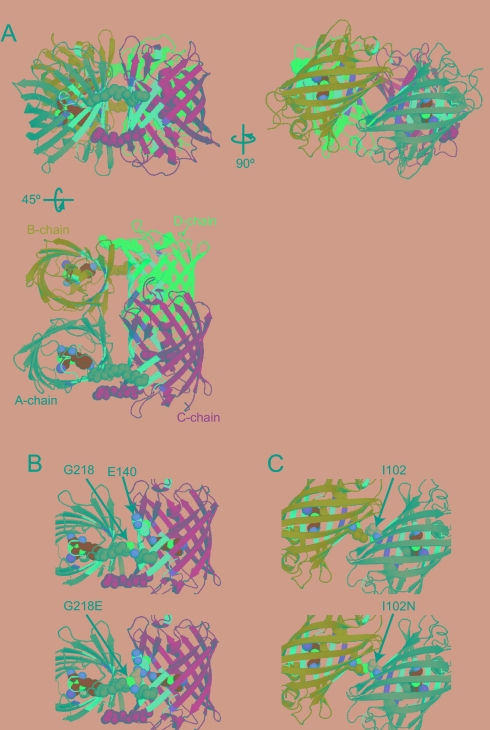

The crystal structure of 22G was determined at 2.3-Å resolution (Fig. 4) and was compared with that of DronpaB. We notice two interesting features in the dimer complex between protomers A and C of 22G. First, the AC dimer interface is mostly composed of a pair of surface regions containing the flexible β-sheets characterized for Dronpa in this study. Second, the C termini of protomers A and C protrude into the interface to stabilize the flexible β-sheets of protomers C and A, respectively (Fig. 4 A and B). This unique C terminus-mediated interaction affects greatly the light-regulated structural flexibility. In fact, the replacement of Gly-218 with Glu conferred significant photochromic performance to 22G (Table 1). This mutation (Gly218Glu) appears to cause withdrawal of the C terminus, probably because of electrical repulsion between Glu-218 and Glu-140 (Fig. 4B). The C terminus-mediated interaction may not be necessary for the dimer formation; the Gly218Glu mutation on 22G preserved its tetrameric complex (Table 1). These results are consistent with the fact that the DronpaB crystal data lack electron density information corresponding to the C terminus (Fig. 1).

Fig. 4.

Quaternary structure of 22G depicted in the cartoon with the chromophore (green, red, and blue spheres for carbon, oxygen, and nitrogen atoms) (PDB ID 2Z6X). Four protomers are depicted in different colors (gray, cyan, yellow, and blue for A, B, C, and D, respectively). The flexible surface regions are highlighted in magenta and orange as in Fig. 2. Main chains of the C-terminal regions are shown in spheres. (A) Tetrameric complex of 22G. Three views at different angles are shown. (B and C) AC–dimer interface (B) and AB–dimer interface (C) are zoomed in. (Upper) Solved crystal structures. (Lower) Modeled structures with substitutions of Gly218Glu (B) and Ile102Asn (C). Residues at 102 and 140 are depicted with spheres.

Table 1.

Mutations crucial for monomerization and photochromism

In contrast, none of the flexible β-sheets was found at the AB dimer interface of 22G (Fig. 4 A and C). One of the critical amino acid residues for the dimer formation is Ile-102; two leucines on protomers A and B show hydrophobic interaction (Fig. 4C). The replacement of Ile-102 with Asn broke up the AB dimer interface partially, but did not induce conversion into the dark state (Table 1).

The 22G mutant carrying Gly218Glu and Ile102Asn is monomeric and photochromic, thus being comparable with Dronpa (Table 1). With the other four mutations initially introduced, 22G can be converted into Dronpa, which is truly monomeric and practically photochromic. Altogether, it is concluded that the flexibility of the surface region at the AC dimer interface is required to reach the dark state and that detachment of the C terminus from the flexible surface is essential to engineer photochromic fluorescent proteins from 22G.

Discussion

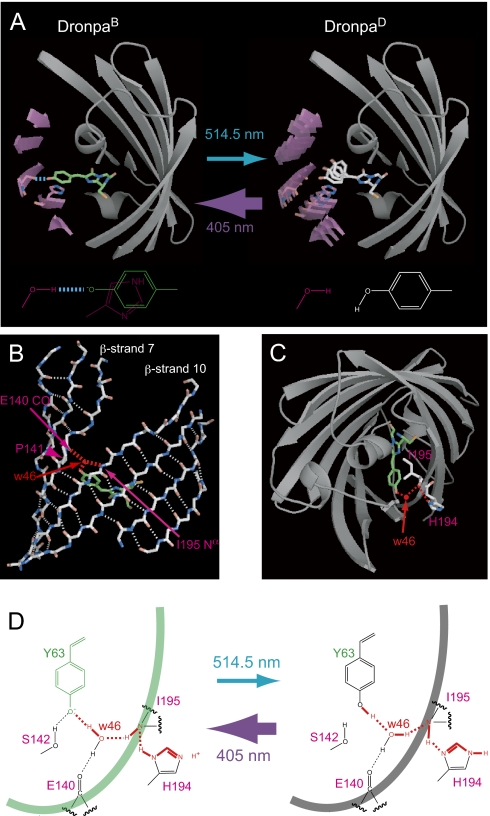

We propose a structural basis for the bright and dark states of Dronpa (Fig. 5A). In the bright state, the chromophore is tethered to the β-barrel through the hydrogen bond between the chromophore hydroxyl oxygen and the Ser-142 hydroxyl group on the barrel wall. This hydrogen bond holds the two rings of the chromophore in a cis configuration. The His-193 imidazole ring is located below the chromophore phenyl moiety and stabilizes the entire chromophore in a coplanar conformation. This rigid structure favors the radiative relaxation process from the first electronic excited state (S1) to the ground state (S0). By contrast, in the dark state, the protonation of the chromophore hydroxyl moiety results in loss of both the hydrogen bond with Ser-142 and the chromophore stacking with His-193. These structural changes increase flexibility of not only the chromophore but also a part of the β-barrel (indicated in purple in Fig. 5A), favoring the nonradiative vibrational relaxation process. In a previous study, Seifert et al. (16) measured H–D exchange of a variant of Aequorea GFP, GFPUV, by NMR and suggested a slightly flexible region on the β-barrel. In contrast, the flexibility we found in DronpaD was remarkable because most of the resonance peaks corresponding to this region were undetectable.

Fig. 5.

A proposed mechanism for the Dronpa photochromism. (A) Schematic of structural flexibility of Dronpa induced by illumination at 514.5 and 405 nm. (Left) The deprotonated chromophore is tethered to and stacked by the β-barrel. The hydrogen bond between the chromophore and the Ser-142 hydroxyl group is indicated (dotted cyan line). (Right) The protonated chromophore is free from the β-barrel. As a result, the chromophore and a part of the β-barrel (purple) are flexible. (B) β-Strands 2, 3, 7, 8, 9, 10, and 11 of the DronpaB crystal structure. Main chains with hydrogen bonds (dotted white lines) are shown. Pro-141 (magenta arrowhead) distorts β-strand 7 to form a crevice. w46 (red arrow) forms hydrogen bonds (dotted red line) with the chromophore hydroxyl moiety, the Ile-195 amino group (magenta arrow), and Glu-140 carbonyl group (magenta arrow). (C) Hydrogen-bond network (dotted red line) connecting the chromophore with His-194. (D) Light-induced rearrangement of the network (red line) that consists of hydrogen bonds (dotted line) and covalent bonds (solid line).

The conversion from DronpaD and DronpaB is primed at the excited states of the protonated and deprotonated states of the chromophore, respectively. The dark-to-bright conversion probably involves the excited-state proton transfer because the acidity of the hydroxyphenyl moiety is likely to be much higher in S1 than S0 (17, 18). By contrast, the bright-to-dark conversion is mysterious. How does the photoexcited chromophore protonate? An intriguing possibility is that the protonation follows an intersystem crossing to the first triplet state (T1). It is generally accepted that the acidity of a phenol ring is lower in T1 than in S1 (19). The long lifetime of T1 may also increase the probability of protonation. Interestingly, the presence of an intersystem crossing pathway after excitation of DronpaB was predicted from a single-molecule analysis of Dronpa (20). Furthermore, the inefficient occurrence of an intersystem crossing may well account for the low quantum yield for the bright-to-dark conversion (0.00032) (4). Additional studies using phosphorescence spectroscopy will be required to understand the mechanism in greater detail. The dark-state electron density calculated from the deposited data appears consistent with a trans conformation for the chromophore, consistent with the interpretation provided by Andresen et al. (8). However, this model is one of several possible interpretations, because the electron density for the hydroxyphenyl group is not well resolved. Consequently, an alternate interpretation may be that multiple chromophore configurations coexist in the crystal, or that the phenolic end is substantially disordered in the dark state. In any case, protonation is the primary process in the bright-to-dark conversion. cis-trans isomerization may occur subsequently. In fact, a quantum chemical calculation predicts that the excited deprotonated chromophore has no driving force to rotate the Cα-Cβ bond for isomerization (21).

The route of protonation of the chromophore may also be deduced from the crystallographic data of DronpaB. There is a crevice on the β-barrel arising from incomplete hydrogen bonding between strands 7 and 10 (Fig. 5B). Ile-195 is located on the rim of the crevice (Fig. 5 B and C). The amino group of Ile-195 may relay protons by interacting with the imidazole ring of His-194 outside and a water molecule (w46) inside the barrel. This water molecule (w46) directly interacts with the chromophore hydroxyl moiety at a distance of 2.78 Å and may regulate protonation. Based on crystallographic and spectroscopic data of Aequorea GFP variants, Agmon (22) has proposed proton pathways across the β-barrel wall. According to this model, chromophore excitation induces a conformational change opening the Thr-203 switch and expelling a proton. In the ground state, the chromophore is reprotonated by Glu-222, which in turn acquires a proton from the surrounding solvent via surface-bound glutamate residues. Thus, the Ile-195-mediated relay of protons that we have identified in Dronpa is unique. Furthermore, proton supply from the solvent is supported by the acid-sensitivity of DronpaB (4). Although the glutamate residue corresponding to Glu-222 in Aequorea GFPs is conserved among all fluorescent proteins, the crystal structure of DronpaB (5) does not reveal that the corresponding residue in Dronpa (Glu-211) supplies protons to the chromophore.

Here, we present a molecular mechanism for photochromism of a fluorescent protein. The mechanism requires a special microenvironment involving a β-barrel, a structure not present in organic photochromic compounds. In the photochromic fluorescent protein, Dronpa, light-induced protonation and deprotonation of the chromophore are intimately linked with changes in flexibility of the surrounding structure. The fluorescence of the protein is regulated by the degree of flexibility of the chromophore but is not necessarily accompanied by cis-trans isomerization. We note that the structurally characterized fluorescent proteins with high quantum yields have cis/coplanar chromophores, whereas those with low-fluorescence quantum yields have trans/noncoplanar chromophores (23–27). Accordingly, cis-trans isomerization of the chromophore in Dronpa has been considered an attractive mechanism for the photochromism of this protein (6, 8, 28). However, whereas structural rigidity is critical for high-fluorescence quantum yield, whether the two rings of the chromophore are in a cis or trans configuration is inconsequential. Notably, Henderson and Remington (29) proposed the importance of structural rigidity for fluorescence. Their study points out that the chromophore of a bright fluorescent protein, amFP486, is stabilized by His-199; a similar interaction between the chromophore and a histidine residue (His-193) is present in DronpaB. In addition, Henderson et al. (30) presented a comprehensive interpretation of the photochromism and cis-trans isomerization for a fluorescent protein mTFP0.7; they demonstrate that the cis isomer is highly ordered, whereas the trans isomer is nonplanar and disordered.

DronpaB has a cis/coplanar chromophore in the rigid β-barrel. We demonstrate structural flexibility of the chromophore and a part of the β-barrel of DronpaD with NMR analyses of both DronpaB and DronpaD in solution. Given the specific characteristics of photochromism in this protein, the critical flexibility within this structure may be difficult to identify by protein crystallography at extremely low temperatures.

Methods

Gene Construction.

For bacterial expression of Dronpa with a histidine tag at the N terminus, an NdeI-EcoRI fragment of Dronpa was inserted into the NdeI/EcoRI site of pET28a vector (Novagen) to generate the plasmid pET28a/Dronpa. For in vitro translation of Dronpa with a histidine tag at the C terminus, an NdeI-XhoI fragment of Dronpa including a C-terminal thrombin cleavage site was inserted into the NdeI-XhoI site of pIVEX2.3d vector (Roche) to generate the plasmid pIVEX2.3d/Dronpa.

Protein Preparation.

For x-ray crystallography, proteins were expressed in Escherichia coli [JM109 (DE3)] transformed with pET28a/Dronpa or pRSET/22G (4) and purified as described (4). The histidine tag was removed by treatment with thrombin (Novagen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. A Ni-NTA agarose column (Qiagen) was then used to obtain Dronpa protein lacking the His-tag. The 22G was used without removing the tag. For NMR measurements, U-13C,15N-labeled Dronpa was prepared according to an established protocol (31). Briefly, E. coli strain BL21(DE3) (Invitrogen) transformed with pET28a/Dronpa was grown at room temperature in M9 media that contained U-13C glucose (2 mg/ml) and 15NH4Cl (1 mg/ml). Protein production was induced by addition of 10 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside. Purification, treatment with thrombin, and removal of the histidine tag were performed as described for x-ray crystallography samples. Specific labeling was carried out by using the RTS 500 ProteoMaster E. coli kit (Roche) using the amino acid mixture containing l-tyrosine-13C9,15N (Isotec) or l-histidine-13C6,15N3 (Isotec) in the presence of the RTS GroE supplement (Roche).

X-Ray Crystallography.

Crystals were grown by the vapor-diffusion method in sitting-drop plates. Diffraction patterns were acquired by using a beamline BL44B2 or BL26B1 at SPring-8. Data were merged and processed by using the HKL2000 package (32). The structure was solved by the molecular replacement technique using the program Molrep (33). A protomer of the DsRed structure (PDB ID 1GGX) was used as a search probe. Crystallographic statistics are summarized in Table S1. The Dronpa crystal on the beamline was illuminated by an argon ion laser (514.5 nm, 150 mW; Melles Griot) and a laser diode (405 nm, 30 mW; Point Source) or a violet light (400DF15) from a 75-W xenon lamp. Fluorescence from the crystal was monitored by using a photonic multichannel analyzer PMA-11 (Hamamatsu Photonics). Structures are depicted with Mac PyMol (www.pymol.org) and TURBO-FRODO (Bio-Graphics).

NMR Spectroscopy.

Proteins were reconstituted at a final concentration of 1 mM in 20 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.5) containing 50 mM NaCl and 2% D2O (Isotec). Resonances were recorded in a Shigemi tube (Shigemi). All spectra except for one-dimensional 1H spectra were acquired at 27°C by using a Bruker AVANCE 600-MHz spectrometer (Bruker BioSpin) equipped with a TCI cryoprobe (Bruker BioSpin). For recording of DronpaD, the sample was continuously illuminated by a 514.5-nm laser line from an argon ion laser (150 mW; Melles Griot) through a multimode optical fiber V50-MM (core diameter, 50 μm; Suruga Seiki,). Sequential resonance assignments for backbone 1HN, 13Cα, 13Cβ, and 15N nuclei for DronpaD and DronpaB were derived from three-dimensional HNCACB and CBCACONH datasets of U-13C,15N-labeled Dronpa. NMR data were processed by using TopSpin (Bruker BioSpin) and CARA (www.nmr.ch). CSD was calculated as described (9).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

We thank H. Hosoi and A. Ohno for fruitful discussion and K. I. Tong, K. Otsuki, and M. Usui for technical assistance. This work was partly supported by grants from the Human Frontier Science Program, Molecular Ensemble Program at RIKEN, Japan MEXT Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research on priority areas, Japan MEXT and Japan Society for the Promotion of Science for Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research B, and Canadian Institutes for Health Research.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data deposition: The coordinates for Dronpa and 22G structures have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, www.pdb.org (PDB ID codes 2Z1O, 2Z6Y, and 2Z6Z for Dronpa and 2Z6X for 22G).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0709599105/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Dürr H, Bouas-Laurent H, editors. Photochromism. Amsterdam: Elsevier; p. 203. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Irie M. Diarylethenes for memories and switches. Chem Rev. 2000;100:1685–1716. doi: 10.1021/cr980069d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berkovic G, Krongauz V, Weiss V. Spiropyrans and spirooxazines for memories and switches. Chem Rev. 2000;100:1741–1753. doi: 10.1021/cr9800715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ando R, Mizuno H, Miyawaki A. Regulated fast nucleocytoplasmic shuttling observed by reversible protein highlighting. Science. 2004;306:1370–1373. doi: 10.1126/science.1102506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wilmann PG, et al. The 1.7 Å crystal structure of Dronpa: A photoswitchable green fluorescent protein. J Mol Biol. 2006;364:213–224. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.08.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stiel AC, et al. Structural basis for reversible photoswitching in Dronpa. Biochem J. 2007;402:35–42. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700629104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nam KH, et al. Structural characterization of the photoswitchable fluorescent protein Dronpa-C62S. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;354:962–967. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.01.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Andresen M, et al. Structural basis for reversible photoswitching in Dronpa. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:13005–13009. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700629104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mal TK, et al. Structural and functional characterization on the interaction of yeast TFIID subunit TAF1 with TATA-binding protein. J Mol Biol. 2004;339:681–693. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tsien RY. The green fluorescent protein. Annu Rev Biochem. 1998;67:509–544. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bertini I, Felli IC, Kümmerle R, Moskau D, Pierattelli R. 13C-13C NOESY: An attractive alternative for studying large macromolecules. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:464–465. doi: 10.1021/ja0357036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Egan W, Shindo H, Cohen JS. On the tyrosine residues of ribonuclease A. J Biol Chem. 1978;253:16–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wilbur DJ, Allerhand A. Titration behavior of individual tyrosine residues of myoglobins from sperm whale, horse, and red kangaroo. J Biol Chem. 1976;251:5187–5194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tyukhtenko SI, et al. NMR studies of the hydrogen bonds involving the catalytic triad of Escherichia coli thioesterase/protease I. FEBS Lett. 2002;528:203–206. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)03308-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Karasawa S, Araki T, Yamamoto-Hino M, Miyawaki A. A green-emitting fluorescent protein from Galaxeidae coral and its monomeric version for use in fluorescence labeling. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:34167–34171. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304063200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Seifert MH, et al. Backbone dynamics of green fluorescent protein and the effect of histidine 148 substitution. Biochemistry. 2003;42:2500–2512. doi: 10.1021/bi026481b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chattoraj M, King BA, Bublitz GU, Boxer SG. Ultra-fast excited state dynamics in green fluorescent protein: Multiple states and proton transfer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:8362–8367. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.16.8362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fron E, et al. Ultra-fast excited state dynamics in green fluorescent protein: Multiple states and proton transfer. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:4870–4871. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Turro NJ. Modern Molecular Photochemistry. Mill Valley, CA: Univ Sci Books; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Habuchi S, et al. Reversible single-molecule photoswitching in the GFP-like fluorescent protein Dronpa. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:9511–9516. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500489102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weber W, Helms V, McCammon JA, Langhoff PW. Shedding light on the dark and weakly fluorescent states of green fluorescent proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:6177–6182. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.11.6177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Agmon M. Proton pathways in green fluorescent protein. Biophys J. 2005;88:2452–2461. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.055541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Prescott M, et al. The 2.2 Å crystal structure of a Pocilloporin pigment reveals a nonpolar chromophore conformation. Structure (London) 2003;11:275–284. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(03)00028-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wilmann PG, Petersen J, Devenish RJ, Prescott M, Rossjohn J. Variations on the GFP chromophore: A polypeptide fragmentation within the chromophore revealed in the 2.1-Å crystal structure of a nonfluorescent chromoprotein from Anemonia sulcata. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:2401–2404. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C400484200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Quillin ML, et al. Kindling fluorescent protein from Anemonia sulcata: Dark-state structure at 1.38 Å resolution. Biochemistry. 2005;44:5774–5787. doi: 10.1021/bi047644u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wilmann PG, et al. The 2.1 Å crystal structure of the far-red fluorescent protein HcRed: Inherent conformational flexibility of the chromophore. J Mol Biol. 2005;349:223–237. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Andresen M, et al. Structure and mechanism of the reversible photoswitch of a fluorescent protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:13070–13074. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502772102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lukyanov KA, Chudakov DM, Lukyanov S, Verkhusha VV. Innovation: Photoactivatable fluorescent proteins. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:885–891. doi: 10.1038/nrm1741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Henderson JN, Remington SJ. Crystal structures and mutational analysis of amFP486, a cyan fluorescent protein from Anemonia majano. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:12712–12717. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502250102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Henderson JN, Ai HW, Campbell RE, Remington SJ. Structural basis for reversible photobleaching of a green fluorescent protein homologue. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:6672–6677. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700059104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ikura M, et al. 3D NMR and isotopic labeling of calmodulin. Towards the complete assignment of the 1H NMR spectrum. Biochem Pharmacol. 1990;40:153–160. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(90)90190-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Otwinowski Z, Minor W. Processing of x-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Methods Enzymol. 1997;276:307–326. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76066-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Collaborative Computational Project. The CCP4 Suite: Programs for Protein Crystallography. Acta Crystallogr D. 1994;50(Number 4):760–763. doi: 10.1107/S0907444994003112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.