Abstract

Background

Currently, only x-ray fluoroscopy is available for visualization of the extrahepatic bile ducts intraoperatively. We hypothesized that with an appropriate fluorophore and imaging system, invisible near-infrared (NIR) light could be used for image-guided procedures on the extrahepatic bile ducts.

Methods

We quantified the performance of three 800 nm NIR fluorophores, differing primarily in their degree of hydrophilicity, for real-time imaging of the extrahepatic bile ducts in rats and pigs: IR-786, indocyanine green (ICG), and the carboxylic form of IRDye™ 800CW (CW800-CA). The signal-to-background ratio (SBR) of the CBD relative to liver and pancreas was measured as a function of the dose of contrast agent, injection site, and kinetics using a previously described intraoperative NIR fluorescence imaging system. Bile samples were examined by high performance liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (HPLC/MS) to determine the chemical form of fluorophores in bile.

Results

Non-sulfonated (IR-786) and di-sulfonated (ICG) NIR fluorophores had poor efficiency and kinetics of excretion into bile. Tetra-sulfonated CW800-CA, however, provided sensitive, specific, and real-time visualization of the extrahepatic bile ducts after a single low-dose given either intraportally or intravenously via systemic vein. A SBR ≥2 provided sensitive assessment of extrahepatic bile duct anatomy and function, including the detection of millimeter-sized, radiolucent inclusions in pigs, for over 30 min post-injection. CW800-CA remained chemically intact after secretion into bile.

Conclusion

The combination of invisible NIR light and an IV injection of CW800-CA provides prolonged, real-time visualization of the extrahepatic bile ducts, without ionizing radiation, and without changing the look of the surgical field.

Keywords: Common Bile Duct, Extrahepatic Ducts, Intraoperative Imaging, Near-Infrared Fluorophores, Near-Infrared Fluorescence Imaging

INTRODUCTION

Intraoperative x-ray cholangiography (IOC), performed by direct injection of iodine contrast medium into the CBD, is used for its anatomic visualization, as well as intraoperative diagnosis of stones and injuries. The use of IOC is still controversial, and opinions are split between routine1,2,3 and selective use.4 Nevertheless, the incidence of CBD stones is approximately 3.3%,5 and the detection rate of CBD abnormalities or injuries intraoperatively is reported in the range of 18 to 37%,6,7,8 suggesting that biliary complications might be detected earlier and more frequently with its routine use.6 In addition, early diagnosis of stones and injuries is reported to improve treatment outcome.5,9,10 Thus, if there were a more convenient method for routine intraoperative assessment of the extrahepatic bile ducts, outcomes might be improved. Intraoperative assessment might also potentially prevent or reduce severe bile duct injuries.

There are various cholegraphic techniques available, including excellent preoperative imaging of stones using ERCP, three-dimensional CT, and MRCP.11,12 However, none of these techniques are ideal for intraoperative imaging. First, it takes a relatively long time (≈30–60 min) to detect the bile duct following administration of contrast agents (CT) or just to perform the study (ERCP and MRCP).13 Second, it is difficult to merge pre-operative scans with what the surgeon sees on the operative field. Third, and most important, iodine-based agents have a low, but clinically relevant, rate of adverse reactions.14,15 Presently, there are no efficient intraoperative imaging modalities for real-time visualization of extrahepatic biliary anatomy and function in the operative field, other than direct injection of iodine contrast agent in conjunction with x-ray fluoroscopy or ultrasonography.

Invisible NIR light in the range of 700 nm to 900 nm has the potential to provide sensitive, specific, and real-time imaging of the extrahepatic bile ducts (reviewed in16). Photon absorption, scatter, and autofluorescence in this wavelength range are relatively low, which provides a low “background” to which a “signal” from exogenous NIR fluorophores can be added. This setting is in sharp contrast to UV and visible wavelength fluorescence,17 which suffer from high background and relatively low signal. We have described previously an intraoperative NIR fluorescence imaging system that simultaneously acquires color video (i.e., surgical anatomy) along with NIR fluorescence of the surgical field.18–20 By introducing an exogenous NIR fluorophore that highlights the target of interest, such as extrahepatic bile ducts, the NIR fluorescence channel can be used to pinpoint the location of any desired structure in the operative field and/or to assess its function. To date, this system has been used for high sensitivity sentinel lymph node mapping,20–32 assessment of tissue and vascular calcification,33–36 assessment of ischemic reperfusion-related cell injury and death,37 detection of obscure gastrointestinal bleeding,38 detection of acute thrombosis,39 and delivery of gene therapy.40

Heptamethine indocyanines are a class of NIR fluorophores for which vast human data are available. The prototype molecule, indocyanine green (ICG), has been FDA-approved for other indications since 1958 and has a remarkable safety record.41,42 In this study, we compare three different 800 nm heptamethine indocyanines differing primarily in their degree of sulfonation, i.e., hydrophilicity. For each compound, we quantify their efficiency of transport from the bloodstream to extrahepatic bile ducts, their SBR in the bile duct over time, and their performance in assessing extrahepatic biliary anatomy and function.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Preparation of NIR Fluorophores

IR−786 perchlorate (IR-786) and sodium ICG were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). CW800-CA, the carboxylic acid form of IRDye™ 800CW was obtained from LI-COR (Lincoln, NE). IR-786 was diluted to 100 μM in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) supplemented with 10% Cremophor EL (Sigma) and 10% absolute ethanol immediately before use. Stock solutions of 10 mM ICG and 18 mM CW800-CA were stored in DMSO at −80ºC in the dark. ICG and CW800-CA were diluted in PBS as indicated below before use. Quantum yields of contrast agents in 100% fetal bovine serum (FBS) were calculated using ICG in dimethyl sulfoxide (quantum yield 13%43) as the calibration standard, under conditions of matched fluorophore absorbance.

Animal Model Systems

Animals were used in accordance with an approved institutional protocol. Adult, male, 330 g, Sprague-Dawley rats from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA) were anesthetized with 65 mg/kg intraperitoneal pentobarbital. Adult, female, 30 kg Yorkshire pigs (E.M. Parsons and Sons, Hadley, MA) were induced with 4.4 mg/kg intramuscular Telazol (Fort Dodge Labs, Fort Dodge, IA), then intubated and maintained with 1.5–2.0% isoflurane/balance O2.

Bile Duct Imaging

Portal vein injection in rats (N = 3 rats per NIR fluorophore) was performed with a 30-gauge, 1/2” needle using the following volumes and concentrations of stock solutions: IR-786 (50 μL of a 100 μM stock; 0.015 μmol/kg final; 9 μg/kg final), ICG (50 μL of a 1 mM stock; 0.15 μmol/kg final; 120 μg/kg final), and CW800-CA (50 μL of a 100 μM stock; 0.015 μmol/kg final; 15 μg/kg final). Fluorescence intensities of the CBD, pancreas, and right lobe of the liver were measured with the same regions of interests at 3, 5, 10, 20, and 30 min following injection of each NIR fluorophore.

For quantifying the dose-response of CW800-CA, the CBD was visualized after systemic (tail vein) IV injection (N = 4 rats per dose) or portal vein injection (N = 4 rats per dose) of 50 μL of CW800-CA having a stock concentration of 10, 20, 50, and 100 μM, corresponding to final doses of 0.0015 μmol/kg (1.5 μg/kg), 0.003 μmol/kg (3 μg/kg), 0.0075 μmol/kg (7.5 μg/kg), and 0.015 μmol/kg (15 μg/kg), respectively. Fluorescence intensities of the CBD, pancreas, and right lobe of the liver were measured with the same regions of interests at 3, 5, 10, 20, and 30 min following injection of each NIR fluorophore.

In anesthetized pigs, 5 mL of 100 μM of CW800-CA (0.015 μmol/kg; 15 μg/kg final) were injected into the portal vein (N = 3 pigs) and 5 mL of either 50 μM (N = 3 pigs; 0.0075 μmol/kg; 7.5 μg/kg) or 100 μM (N = 3 pigs; 0.015 μmol/kg; 15 μg/kg) of CW800-CA were injected systemically (ear vein). Radiolucent globular beads (2.5 mm in diameter) or cylindrical beads (3.5 mm in long axis) were inserted into the CBD via the papilla of Vater after duodenotomy (N = 2 pigs). These were used to simulate different sizes and shapes of CBD stones seen in patients. An additional N = 2 pigs received direct injection of 10 ml of 10 μM ICG into the cystic duct.

A previously described20 simultaneous color video/NIR fluorescence intraoperative imaging system was employed for quantification of all NIR fluorescence images. White light (400–700 nm) and NIR fluorescence excitation light (725–775 nm) was used at 1 mW/cm2 and 5 mW/cm2, respectively. Spatial resolution at a field-of-view of 20 × 15 cm is 625 μm, and at a field-of-view of 4 × 3 cm is 125 μm. After computer-controlled camera acquisition via custom LabVIEW (National Instruments, Austin, TX) software, anatomic (white light) and functional (NIR fluorescence light) images were displayed separately and merged. To create a single image that displays both anatomy (color video) and function (NIR fluorescence), the NIR fluorescence image was pseudo-colored in lime green and overlaid with 100% transparency on top of the color video image of the same surgical field. All images were refreshed up to 15 times per second. The entire apparatus was suspended on an articulated arm over the surgical field, thus permitting non-invasive and non-intrusive imaging. Hands-free operation utilizing motorized zoom and focus lenses, a four-pedal footswitch, and a multifunction data acquisition board were described in detail previously.44

Gel-Filtration Chromatography

Bile was collected from the CBD using a needle and syringe, flash frozen in LN2, and stored at −80°C until analyzed. After thawing, samples were diluted immediately 1:1 in phosphate-buffered saline, pH 7.4 (PBS) and separated using an AKTA Prime chromatography system (Amersham Bioscience, Piscataway, NJ) equipped with an Econo-Pac P6 (6,000 MW cutoff; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) gel-filtration cartridge. The mobile phase was PBS and the flow rate was 0.5 ml/min. Online, full-spectrum absorbance (200–1100 nm) and fluorescence (350–1000 nm) were measured as described in detail previously.45 Fractions having the highest 783 nm absorbance and 803 nm fluorescence were collected for analysis by mass spectrometry.

High-Performance Liquid Chromatography/Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC/MS)

Twenty-five microliters of each gel-filtration sample was analyzed on a Waters (Milford, MA) LCT electrospray (ES) time-of-flight (TOF) LC/MS equipped with dual-absorbance detectors, fluorescence detector, Sedex model 75 evaporative light scatter detector (ELSD; Richards Scientific, Novato, CA), and lockspray, as described in detail previously.46 Briefly, the absorbance detectors were set to 280 nm and 700 nm (the maximum permitted wavelength). The fluorescence detector was set to 803 nm using 770 nm excitation light. Bovine heart myoglobin (5 μM) in water was used as a mass reference for the lockspray. Buffer A was 10 mM triethylammonium acetate (TEAA; Glen Research, Sterling, VA) and Buffer B was absolute methanol (Aaper Alcohol and Chemical, Shelbyville, KY). Using a gradient of 0 to 70% B over 20 min, bile samples were resolved on a 4.6 × 150 mm Symmetry (Waters) C18 column at a flow rate of 1 ml/min, with the eluate split equally to the ELSD and MS detectors. The ion mode was set to ES−, and cone and capillary voltages were 30 V and 3000 V, respectively. Desolvation and source temperature were 350°C and 140°C, respectively. Data were analyzed with MassLynx (Waters) software.

RESULTS

NIR Fluorescent Contrast Agents for Imaging the Extrahepatic Bile Ducts

The heptamethine indocyanines IR-786, ICG, and CW800-CA possess 0, 2, and 4 sulfonate groups, respectively, and hence increasing hydrophilicity (Figure 1A). Although all three have similar chemical structures and peak emission wavelengths ≈800 nm, their quantum yield in serum increases with hydrophilicity. So, too, does the efficiency of excretion into bile (this study) and urine47 after intravenous injection, with the tetra-sulfonated compound CW800-CA showing superior performance.

Figure 1. NIR fluorescent contrast agents for real-time assessment of the extrahepatic bile ducts.

A. Chemical structures (top) of IR-786, ICG, and CW800-CA and their optical properties (bottom) in fetal bovine serum (FBS).

B. CBD imaging in rat 10 min after portal vein injection of 0.015 μmol/kg IR-786 (top row), 0.15 μmol/kg ICG (middle row), and 0.015 μmol/kg CW800-CA (bottom row). Shown are the color video (left), NIR fluorescence (middle), and pseudo-colored (lime green) merged images of the two (right). The CBD is marked with a white arrow. NIR fluorescence exposure time is 100 msec. Images are representative of N = 3 independent animals studied per contrast agent.

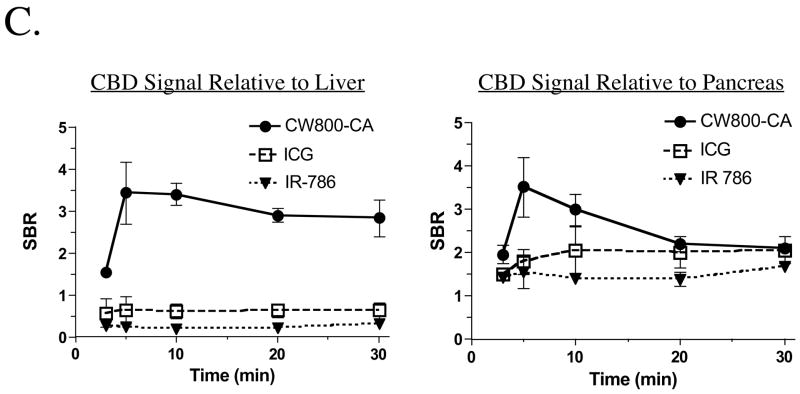

C. Quantification of the SBR in the CBD over time. The SBR (mean ± SEM) of the CBD relative to liver (left) and pancreas (right) was quantified over time after portal vein injection of IR-786, ICG, and CW800-CA as described in Figure 1B.

Portal Vein Injection of NIR Fluorescent Contrast Agents

To optimize visualization of the extrahepatic bile ducts, NIR fluorescent contrast agents were injected initially into the portal vein. As shown in Figure 1B, all three agents provided image-guided identification of the extrahepatic bile ducts but differed greatly in their performance. IR-786 and ICG were excreted poorly into bile with an extremely low signal relative to liver background. Also, ICG required ten-fold higher doses to achieve reasonable bile duct labeling. On the contrary, CW800-CA was transferred from the liver into bile with extremely low liver retention (Figure 1B) and background (Figure 1C). Indeed, a single portal vein injection of CW800-CA resulted in an SBR ≥2.5 starting 3 min after injection, peaking at 5–10 min and continuing for at least 30 min. The dose-response curve of CW800-CA (Figure 2, top) suggested that doses greater than 0.0015 μmol/kg provided the highest SBR, with a dose of 0.0075–0.015 μmol/kg being optimal for prolonged visualization.

Figure 2.

The SBR dose-response of CW800-CA for CBD imaging. The SBR (mean ± SEM) of the CBD relative to liver (left) and pancreas (right) was quantified over time, following portal vein injection (top) or systemic IV injection (bottom) of CW800-CA, at the doses shown, in N = 3 animals per dose.

Systemic Injection of NIR Fluorescent Contrast Agents

Because injection into the portal vein injection is not ideal, we next determined whether a simple, peripheral IV injection of CW800-CA would permit sensitive imaging of the extrahepatic bile ducts. As shown in Figure 2 (bottom), a single IV injection of CW800-CA into rats at doses greater than 0.0015 μmol/kg resulted in a high SBR of the CBD for at least 30 min post-injection, with a dose of 0.0075 μmol/kg being optimal.

Visualization of Normal and Abnormal Bile Ducts in Large Animal Model Systems

Based on the results from rats, CW800-CA was chosen for large animal studies. Initial dose-response curves (data not shown) suggested that a dose of 0.015 μmol/kg injected into the portal vein (N = 3 pigs), and either 0.0075 μmol/kg (N = 3 pigs) or 0.015 μmol/kg (N = 3 pigs) injected systemically, resulted in SBR ≥2.5 starting from 5 min and continuing for at least 30 min post-injection. Figure 3A shows representative imaging of the normal extrahepatic bile duct system after a single systemic IV injection of 0.0075 μmol/kg CW800-CA. Visualization lasted at least 30 min, and the systemic injection could be repeated as many times as necessary (data not shown) to complete the operation. Importantly, contrast in the CBD is great enough to detect the presence of small (2.5–3.5 mm) radiolucent inclusions (Figure 3B). Because ICG is already FDA-approved for other indications and is available in the clinic, and since neither portal vein nor systemic injection results in a high and predictable biliary concentration (Figure 1B), we tested the direct injection of ICG into the extrahepatic bile duct via the cystic duct. A dose of 10 μM was chosen, because it provides the highest possible fluorescence emission without dye quenching.24 As shown in Figure 3C, direct injection provided immediate imaging of both distal and proximal extrahepatic bile ducts with an SBR ≥3 for over 30 min.

Figure 3. CBD visualization and assessment in large animals approaching the size of humans.

A. Typical visualization of the CBD 15 min after systemic IV injection of 0.0075 μmol/kg CW800-CA, showing the left (L) hepatic duct, right (R) hepatic duct, and common (C) bile ducts. Shown are the color video (left), NIR fluorescence (middle), and merged images of the two (right). NIR fluorescence exposure time was 100 msec. Image is representative of N = 9 animals total.

B. Detection of three spherical radiolucent inclusions of 2.5 mm diameter (arrowhead) and one cylindrical radiolucent inclusion of 3.5 mm long axis (arrow) using CW800-CA as described in Figure 3A. Image is representative of N = 2 animals total.

C. NIR fluorescence IOC was performed by direct injection of 10 ml of 10 μM ICG into the cystic duct (Cy). Visualization of the CBD (arrowhead) and the proximal second order branch of the left hepatic duct (L) is shown.

Analysis of NIR Fluorophore Chemical Form in Bile

Although there was an NIR fluorescent substance in bile after intravenous injection of CW800-CA, it is possible that the fluorophore was metabolized during excretion. To determine the chemical form of the NIR fluorophore in bile, a combination of gel-filtration and LC/MS analyses were performed. As shown in Figure 4A, separation of control bile on a 6,000 Da cutoff column confirmed that there are no endogenous NIR fluorophores present. Separation of bile aspirated from the CBD 15 min after injection of 0.015 μmol/kg CW800-CA demonstrated that 94% of the NIR fluorescence was non-protein bound, running at ≈1,000 Da in size. The peak fraction was collected and subjected to LC/MS analysis using a C18 column for separation. As shown in Figure 4B, a single NIR absorbing and fluorescing peak was present, with a retention time (21 min) and mass spectrometric pattern identical to pure CW800-CA. These data suggest that ≈94% of CW800-CA is excreted unchanged into bile and is the major contributor to the 800 nm NIR fluorescence signal in the extrahepatic bile ducts.

Figure 4. LC/MS analysis of bile.

A. Initial separation of low molecular weight (<6,000 Da) components of bile by gel-filtration. Shown are chromatograms for control bile (left) and bile collected 15 min after intravenous injection of 0.015 μmol/kg CW800-CA (right). The fraction collected from the post-contrast specimen for LC/MS analysis is marked with an arrow.

B. LC/MS analysis of pure CW800-CA (left) and the bile fraction described in Figure 4A (right). Shown are the absorbance at 700 nm (top tracings), fluorescence at 803 nm (middle tracings), and mass spectrographs of the 21 min peak (bottom tracings).

DISCUSSION

NIR fluorescence bile duct imaging offers several advantages over IOC by x-ray fluoroscopy including prolonged (at least 30 min), high sensitivity visualization after a single, low-dose, systemic injection, no exposure of patients and caregivers to ionizing radiation, real-time imaging with no moving parts, patient contact, or image reconstruction, and simultaneous acquisition of surgical anatomy (via color video) and bile duct function (via NIR fluorescence). Contrast agents can be stored as dry powders in sterile vials, and resuspended in sterile saline immediately prior to use. Contrast agent injection can also be repeated as many times as needed for long cases. And, bile duct injury can be detected in real-time using this technology (data not shown), as we described previously for ureteral injury.47 Moreover, because both NIR fluorescence excitation and emission light is invisible to the surgeon, and the NIR fluorophores are used at extremely low doses, there is no alteration to the look of the surgical field.

However, several limitations deserve mention. First, peak contrast doesn’t occur for approximately 10 min after IV injection. Second, NIR light has finite depth penetration into scattering tissue, which limits detection to 3–5 mm from the surface. However, at least in rats and pigs, there was never much difficulty in finding quickly and assessing the CBD, because autofluorescence from surrounding structures is low, and the SBR is relatively high. And, third, IV injection of a contrast agent always carries the risk of toxicity. CW800-CA, however, belongs to a class of heptamethine indocyanines with low inherent toxicitiy.48 In fact, the chemically-related molecule ICG has one of the lowest reported toxicities for any pharmaceutical administered to patients,41 with toxicity seen only at doses 10-fold higher than those used in the present study.

The chemical form and injection dose of the NIR fluorescent contrast agent are of critical importance for successful visualization of the extrahepatic bile ducts using this technology. First, there appears to be an important effect of sulfonation, and therefore hydrophilicity, on the efficiency of transfer of NIR fluorescent contrast agents from the bloodstream to the bile. Indeed, the excretion of the tetra-sulfonated compound CW800-CA occurred so quickly that the background signal in the liver was barely detectable (Figures 1B and 3). On the contrary, non-sulfonated IR-786 and di-sulfonated ICG had tremendously high liver uptake and poor efficiency of excretion into bile.

An optimal dose of CW800-CA would result in a final CBD concentration of ≈10 μM, which is the concentration at which fluorescence emission reaches its peak, and dye stacking and quenching are minimal.24 As demonstrated in Figure 2, increasing the dose beyond its optimum results in a lower SBR in the CBD. It also results in the tinting of bile slightly green (the color of CW800-CA in solution), indicating that the concentration in the CBD is too high and fluorescence quenching is occurring. Nevertheless, at least 94% of CW800-CA remains non-protein bound in bile and is chemically unchanged. This observation, coupled with the low dose required (0.0075 μmol/kg or 250 μg in a 33 kg pig), and the chemical similarity to ICG, suggests that translation to the clinic in the near-term should be possible.

Although open surgery for gallbladder disease is still being performed, laparoscopic surgery plays an ever more important role. For this reason, we have adapted our NIR fluorescence imaging system for laparoscopic surgery (unpublished data). The importance of the present study, though, is that the NIR fluorescent contrast agent chemistry for imaging of the extrahepatic biliary system is now defined, and can be applied equally to open surgery and laparoscopic surgery to permit real-time, image-guided assessment of the anatomy and function of the extrahepatic bile ducts.

Acknowledgments

We thank Alice L. Gugelmann for editing, Barbara L. Clough for proofing, and Eugenia Trabucchi for administrative assistance. This work was funded by NIH grants R01-CA-115296 and R01-EB-005805 to JVF.

Funding Sources: This work was funded by NIH grants R01-CA-115296 and R01-EB-005805 to JVF.

ABBREVIATIONS

- CBD

common bile duct

- CT

computed tomography

- ERCP

endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography

- ICG

indocyanine green

- IOC

intraoperative cholangiography

- IV

intravenous

- MRCP

magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography

- NIR

near-infrared

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline, pH 7.4, SBR, signal-to-background ratio

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Caputo L, Aitken DR, Mackett MC, Robles AE. Iatrogenic bile duct injuries. The real incidence and contributing factors--implications for laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Am Surg. 1992;58:766–771. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moossa AR, Mayer AD, Stabile B. Iatrogenic injury to the bile duct. Who, how, where? Arch Surg. 1990;125:1028–1030. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1990.01410200092014. discussion 1030–1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fletcher DR, Hobbs MS, Tan P, Valinsky LJ, Hockey RL, Pikora TJ, et al. Complications of cholecystectomy: risks of the laparoscopic approach and protective effects of operative cholangiography: a population-based study. Ann Surg. 1999;229:449–457. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199904000-00001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Piacentini F, Perri S, Pietrangeli F, Nardi M, Jr, Dalla Torre A, Nicita A, et al. [Intraoperative cholangiography during laparoscopic cholecystectomy: selective or routine?] G Chir. 2003;24:123–128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nickkholgh A, Soltaniyekta S, Kalbasi H. Routine versus selective intraoperative cholangiography during laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a survey of 2,130 patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Endosc. 2006;20:868–874. doi: 10.1007/s00464-005-0425-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Woods MS, Traverso LW, Kozarek RA, Donohue JH, Fletcher DR, Hunter JG, et al. Biliary tract complications of laparoscopic cholecystectomy are detected more frequently with routine intraoperative cholangiography. Surg Endosc. 1995;9:1076–1080. doi: 10.1007/BF00188990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lillemoe KD, Melton GB, Cameron JL, Pitt HA, Campbell KA, Talamini MA, et al. Postoperative bile duct strictures: management and outcome in the 1990s. Ann Surg. 2000;232:430–441. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200009000-00015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chaudhary A, Manisegran M, Chandra A, Agarwal AK, Sachdev AK. How do bile duct injuries sustained during laparoscopic cholecystectomy differ from those during open cholecystectomy? J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2001;11:187–191. doi: 10.1089/109264201750539682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Inui H, Kwon AH, Kamiyama Y. Managing bile duct injury during and after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 1998;5:445–449. doi: 10.1007/s005340050070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.MacFadyen BV, Jr, Vecchio R, Ricardo AE, Mathis CR. Bile duct injury after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. The United States experience. Surg Endosc. 1998;12:315–321. doi: 10.1007/s004649900661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Breen DJ, Nicholson AA. The clinical utility of spiral CT cholangiography. Clin Radiol. 2000;55:733–739. doi: 10.1053/crad.2000.0511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dalton SJ, Balupuri S, Guest J. Routine magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography and intra-operative cholangiogram in the evaluation of common bile duct stones. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2005;87:469–470. doi: 10.1308/003588405X51137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krueger P. [Clinical comparative study between the contrast media Biligram, Endomirabil and Biliscopin (author’s transl)] Rontgenblatter. 1978;31:360–364. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tischendorf P. [Quality of roentgenological visualization and tolerance of various intravenous cholegraphic contrast media (author’s transl)] Rontgenblatter. 1980;33:581–587. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nilsson U. Adverse reactions to iotroxate at intravenous cholangiography. A prospective clinical investigation and review of the literature. Acta Radiol. 1987;28:571–575. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Frangioni JV. In vivo near-infrared fluorescence imaging. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2003;7:626–634. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2003.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oddi A, Mills CO, Custureri F, Di Nicola V, Elias E, Di Matteo G. Intraoperative biliary tree imaging with cholyl-lysyl-fluorescein: an experimental study in the rabbit. Surg Laparosc Endosc. 1996;6:198–200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.De Grand AM, Frangioni JV. An operational near-infrared fluorescence imaging system prototype for large animal surgery. Technol Cancer Res Treat. 2003;2:553–562. doi: 10.1177/153303460300200607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nakayama A, del Monte F, Hajjar RJ, Frangioni JV. Functional near-infrared fluorescence imaging for cardiac surgery and targeted gene therapy. Mol Imaging. 2002;1:365–377. doi: 10.1162/15353500200221333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tanaka E, Choi HS, Fujii H, Bawendi MG, Frangioni JV. Image-Guided Oncologic Surgery Using Invisible Light: Completed Pre-Clinical Development for Sentinel Lymph Node Mapping. Ann Surg Oncol. 2006 doi: 10.1245/s10434-006-9194-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim S, Lim YT, Soltesz EG, De Grand AM, Lee J, Nakayama A, et al. Near-infrared fluorescent type II quantum dots for sentinel lymph node mapping. Nat Biotechnol. 2004;22:93–97. doi: 10.1038/nbt920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Parungo CP, Ohnishi S, De Grand AM, Laurence RG, Soltesz EG, Colson YL, et al. In vivo optical imaging of pleural space drainage to lymph nodes of prognostic significance. Ann Surg Oncol. 2004;11:1085–1092. doi: 10.1245/ASO.2004.03.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim SW, Zimmer JP, Ohnishi S, Tracy JB, Frangioni JV, Bawendi MG. Engineering InAs(x)P(1-x)/InP/ZnSe III-V alloyed core/shell quantum dots for the near-infrared. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:10526–10532. doi: 10.1021/ja0434331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ohnishi S, Lomnes SJ, Laurence RG, Gogbashian A, Mariani G, Frangioni JV. Organic alternatives to quantum dots for intraoperative near-infrared fluorescent sentinel lymph node mapping. Mol Imaging. 2005;4:172–181. doi: 10.1162/15353500200505127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Parungo CP, Colson YL, Kim SW, Kim S, Cohn LH, Bawendi MG, et al. Sentinel lymph node mapping of the pleural space. Chest. 2005;127:1799–1804. doi: 10.1378/chest.127.5.1799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Parungo CP, Ohnishi S, Kim SW, Kim S, Laurence RG, Soltesz EG, et al. Intraoperative identification of esophageal sentinel lymph nodes with near-infrared fluorescence imaging. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2005;129:844–850. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2004.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Soltesz EG, Kim S, Laurence RG, DeGrand AM, Parungo CP, Dor DM, et al. Intraoperative sentinel lymph node mapping of the lung using near-infrared fluorescent quantum dots. Ann Thorac Surg. 2005;79:269–277. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2004.06.055. discussion 269–277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Soltesz EG, Kim S, Kim SW, Laurence RG, De Grand AM, Parungo CP, et al. Sentinel lymph node mapping of the gastrointestinal tract by using invisible light. Ann Surg Oncol. 2006;13:386–396. doi: 10.1245/ASO.2006.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zimmer JP, Kim SW, Ohnishi S, Tanaka E, Frangioni JV, Bawendi MG. Size series of small indium arsenide-zinc selenide core-shell nanocrystals and their application to in vivo imaging. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:2526–2527. doi: 10.1021/ja0579816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Frangioni JV, Kim SW, Ohnishi S, Kim S, Bawendi MG. Sentinel lymph node mapping with type-II quantum dots. Methods Mol Biol. 2007;374:147–159. doi: 10.1385/1-59745-369-2:147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Knapp DW, Adams LG, Degrand AM, Niles JD, Ramos-Vara JA, Weil AB, et al. Sentinel Lymph Node Mapping of Invasive Urinary Bladder Cancer in Animal Models Using Invisible Light. Eur Urol. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2007.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Parungo CP, Soybel DI, Colson YL, Kim SW, Ohnishi S, DeGrand AM, et al. Lymphatic drainage of the peritoneal space: a pattern dependent on bowel lymphatics. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14:286–298. doi: 10.1245/s10434-006-9044-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zaheer A, Murshed M, De Grand AM, Morgan TG, Karsenty G, Frangioni JV. Optical imaging of hydroxyapatite in the calcified vasculature of transgenic animals. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26:1132–1136. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000210016.89991.2a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Humblet V, Lapidus R, Williams LR, Tsukamoto T, Rojas C, Majer P, et al. High-affinity near-infrared fluorescent small-molecule contrast agents for in vivo imaging of prostate-specific membrane antigen. Mol Imaging. 2005;4:448–462. doi: 10.2310/7290.2005.05163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lenkinski RE, Ahmed M, Zaheer A, Frangioni JV, Goldberg SN. Near-infrared fluorescence imaging of microcalcification in an animal model of breast cancer. Acad Radiol. 2003;10:1159–1164. doi: 10.1016/s1076-6332(03)00253-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zaheer A, Lenkinski RE, Mahmood A, Jones AG, Cantley LC, Frangioni JV. In vivo near-infrared fluorescence imaging of osteoblastic activity. Nat Biotechnol. 2001;19:1148–1154. doi: 10.1038/nbt1201-1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ohnishi S, Vanderheyden JL, Tanaka E, Patel B, De Grand AM, Laurence RG, et al. Intraoperative Detection of Cell Injury and Cell Death with an 800 nm Near-Infrared Fluorescent Annexin V Derivative. Am J Transplant. 2006;6:2321–2331. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2006.01469.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ohnishi S, Garfein ES, Karp SJ, Frangioni JV. Radiolabeled and Near-Infrared Fluorescent Fibrinogen Derivatives Create a system for the identification and Repair of Obscure Gastrointestinal Bleeding. Surgery. 2006;140:785–792. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2006.03.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Flaumenhaft R, Tanaka E, Graham GJ, De Grand AM, Laurence RG, Hoshino K, et al. Localization and quantification of platelet-rich thrombi in large blood vessels with near-infrared fluorescence imaging. Circulation. 2007;115:84–93. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.643908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hayase M, del Monte F, Kawase Y, MacNeill BD, McGregor J, Yoneyama R, et al. Catheter-based antegrade intracoronary viral gene delivery with coronary venous blockade. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;288:2995–3000. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00703.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Benya R, Quintana J, Brundage B. Adverse reactions to indocyanine green: a case report and a review of the literature. Cathet Cardiovasc Diagn. 1989;17:231–233. doi: 10.1002/ccd.1810170410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hope-Ross M, Yannuzzi LA, Gragoudas ES, Guyer DR, Slakter JS, Sorenson JA, et al. Adverse reactions due to indocyanine green. Ophthalmology. 1994;101:529–533. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(94)31303-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Benson C, Kues HA. Absorption and fluorescence properties of cyanine dyes. J Chem Eng Data. 1977;22:379–383. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gioux S, De Grand AM, Lee DS, Yazdanfarc S, Idoine JD, Lomnes SJ, et al. Improved optical sub-systems for intraoperative near-infrared fluorescence imaging. Proc of SPIE. 2005;6009:39–48. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Frangioni JVKS, Ohnishi S, Kim S, Bawendi MG. Sentinel node mapping with type II quantum dots. Methods Mol Biol. 2006 doi: 10.1385/1-59745-369-2:147. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Humblet VMP, Frangioni JV. An HPLC/Mass Spectrometry Platform for the Development of Multimodality Contrast Agents and Targeted Therapeutics: Prostate-Specific Membrane Antigen Small Molecule Derivatives. Contrast Med Mol Imag. 2006;4:448–462. doi: 10.1002/cmmi.106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tanaka E, Ohnishi S, Laurence RG, Choi HS, Humblet V, Frangioni JV. Real-time intraoperative ureteral guidance using invisible near-infrared fluorescence. J Urol. 2007;178:2197–2202. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.06.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Miwa N, Inagaki M, Eguchi H, Okumura M, Inagaki Y, Harada T. Near-infrared fluorescent contrast agent and fluorescence imaging. WO 00/16810. Patent Cooperation Treaty. 2000