Abstract

α2-Macroglobulin (α2M) is a plasma protease inhibitor, which reversibly binds growth factors and, in its activated form, binds to low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein (LRP-1), an endocytic receptor with cell signaling activity. Because distinct domains in α2M are responsible for its various functions, we hypothesized that the overall effects of α2M on cell physiology reflect the integrated activities of multiple domains, some of which may be antagonistic. To test this hypothesis, we expressed the growth factor carrier site and the LRP-1 recognition domain (RBD) as separate GST fusion proteins (FP3 and FP6, respectively). FP6 rapidly and robustly activated Akt and ERK/MAP kinase in Schwann cells and PC12 cells. This response was blocked by LRP-1 gene silencing or by co-incubation with the LRP-1 antagonist, receptor-associated protein. The activity of FP6 also was blocked by mutating Lys1370 and Lys1374, which precludes LRP-1 binding. FP3 blocked activation of Akt and ERK/MAP kinase in response to nerve growth factor-β (NGF-β) but not FP6. In PC12 cells, FP6 promoted neurite outgrowth and expression of growth-associated protein-43, whereas FP3 antagonized the same responses when NGF-β was added. The ability of FP6 to trigger LRP-1-dependent cell signaling in PC12 cells was reproduced by the 18-kDa RBD, isolated from plasma-purified α2M by proteolysis and chromatography. We propose that the effects of intact α2M on cell physiology reflect the degree of penetration of activities associated with different domains, such as FP3 and FP6, which may be regulated asynchronously by conformational change and by other regulatory proteins in the cellular microenvironment.

α2-Macroglobulin (α2M)2 is a 718-kDa homotetrameric glycoprotein, found in the plasma and extracellular spaces, which was first recognized as a broad spectrum protease inhibitor (1). Reaction with proteases induces a major conformational change in α2M so that the protease is physically trapped (2, 3). The same conformational change reveals a cryptic recognition site for low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein (LRP-1) (4, 5). Because of the function of LRP-1 as an endocytic receptor, α2M-protease complexes are rapidly cleared from the bloodstream and probably other sites of generation (6).

In addition to its role as a protease inhibitor, α2Misan important carrier of specific growth factors, including transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), platelet-derived growth factor-BB (PDGF-BB), nerve growth factor-β (NGF-β), and neurotrophin-4 (7, 8). α2M-carrier interactions are principally reversible in nature (7). As a result, α2M may inhibit growth factor activity (9, 10) or stabilize the growth factor for potential delivery to cell signaling receptors (11). There also is evidence that α2M, which is “activated” by reaction with proteases, initiates cell signaling by binding to LRP-1 (12–15) or other receptors, such as glucose-regulated protein-78 (Grp 78) (16, 17). However, in studies with intact α2M, the possibility that cell signaling results from growth factors that are carried by α2M must be considered (11, 18).

A structural model of α2M has been developed, based on the crystal structure of complement component C3, which is homologous to α2M (19). This model describes α2M as a modular structure, consisting of multiple independently folded domains. To localize α2M domains that are responsible for various activities, our laboratory generated a library of glutathione S-transferase (GST) fusion proteins, containing overlapping segments of the α2M subunit (20–22). Fusion protein-3 (FP3) includes residues 591–774 and contains the sequence in α2M responsible for binding growth factors. FP6 contains amino acids 1242–1451 and the LRP-1-binding site, in which a single α-helix that includes Lys1370 and Lys1374 plays a central role (23, 24). Assignment of α2M activities to specific fusion proteins, such as FP3 and FP6, has been validated by mutagenesis of full-length recombinant α2M (25, 26). Thus, the α2M fusion proteins provide an opportunity to assess activities assigned to different α2M domains independently.

Given the modular structure of α2M and the important activities assigned to various domains, it is not surprising that α2M gene knock-out mice demonstrate abnormal responses to a variety of exogenous challenges (27–31). It is also not surprising that in vitro studies of α2M and its homologues, using closely related experimental model systems, have yielded differing results. For example, in cultures of rat PC12 pheochromocytoma cells and mouse cortical neurons, α2M and related proteins have been reported to either promote or inhibit neurite outgrowth (13, 32, 33).

In this study, we examined cell signaling in response to α2M-peptide fusion proteins, in which different α2M activities have been isolated, in Schwann cells and PC12 cells. We also studied neuritogenesis and expression of growth-associated protein (GAP-43), a neuronal differentiation marker (34), in PC12 cells. Our results show for the first time that different regions of α2M demonstrate antagonistic activities. How these activities are integrated in the intact protein may be regulated by α2M conformational change and by the presence of other regulatory molecules in the cellular microenvironment.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Proteins and Reagents—α2M was purified from human plasma by the method of Imber and Pizzo (35). α2M was activated for binding to LRP-1 by dialysis against 200 mm methylamine-HCl in 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.2, for 12 h at 22 °C and then exhaustively against 20 mm sodium phosphate, 150 mm NaCl, pH 7.4. Modification of α2M by methylamine in the final preparation (α2M-MA) was confirmed by demonstrating the characteristic increase in α2M electrophoretic mobility by non-denaturing PAGE (2). The 18-kDa receptor-binding domain (RBD) of α2M was generated by treating α2M-MA with papain and purified by chromatography, as previously described (4). Receptor-associated protein was expressed as a GST fusion protein (GST-RAP) in bacteria and purified as previously described (37). GST-RAP binds to LRP-1 and blocks the binding of all other LRP-1 ligands (38). As a control, we expressed GST in bacteria transformed with the empty vector, pGEX-2T. Purified GST-RAP and GST were subjected to chromatography on Detoxi-Gel endotoxin-removing columns (Pierce). Rabbit polyclonal antibodies specific for phosphorylated Akt, phosphorylated extracellular signal-regulated kinase-1/2 (ERK/MAP kinase), total ERK/MAP kinase, and horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling Technologies (Santa Cruz, CA). Monoclonal antibody specific for β-actin and p-nitrophenyl p-guanidinebenzoate (pNPGB) were from Sigma. NGF-β was purchased from Invitrogen (San Diego, CA). Recombinant rat PDGF-BB was from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). Recombinant human erythropoietin (Epo) was purchased from Johnson & Johnson (San Diego, CA). Polyclonal α2M-specific antibody was from Dako (Carpinteria, CA).

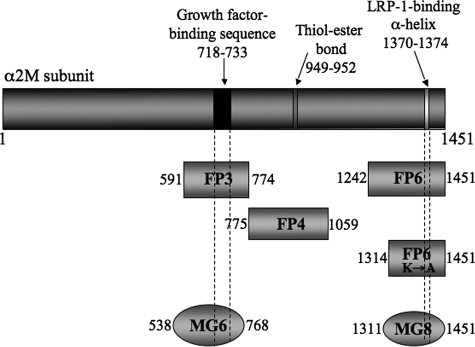

α2M Peptide-GST Fusion Proteins—Three previously described GST fusion proteins that include segments of the human α2M sequence were expressed in BL-21 cells (20–22). These include: FP3 (amino acids 591–774), FP4 (amino acids 775–1059), and FP6 (amino acids 1242–1451). FP3 includes the characterized binding site for growth factors (20, 21, 25). FP6 contains the LRP-1 recognition sequence (22). A construct encoding FP6, in which Lys1370 and Lys1374 are mutated to Ala (FP6(K → A)), was previously described (22). These mutations abrogate α2M binding to LRP-1 (23, 24). All of the fusion proteins were partially purified from induced bacterial suspensions by selective detergent extraction (20). FP3, FP4, FP6, and FP6(K → A) were then further purified to homogeneity by chromatography on glutathione-Sepharose. The resulting preparations yielded clearly defined bands, with the correct molecular masses when assessed by Coomassie Blue staining of SDS gels or immunoblot analysis with GST-specific antibody (20, 22). All of the GST fusion proteins were subjected to endotoxin decontamination. Fig. 1 shows the α2M sequences encoded by the fusion proteins studied here, and the relationship of these fusion proteins to the predicted domains in α2M, as described by Doan and Gettins (19). The growth factor-binding site, expressed in FP3, is contained within the MG6 domain and the LRP-1 recognition site, which is encoded in FP6, is part of the MG8 domain.

FIGURE 1.

Sequences of α2M peptide-GST fusion proteins. The amino acid numbering is based on the mature α2M subunit. The fusion protein FP3-(591–774) includes the characterized binding site for growth factors. FP4 has no known activity. FP6 includes the α-helix and two Lys residues (Lys1370 and Lys1374), which are essential for LRP-1 binding. In FP6(K → A), Lys1370 and Lys1374 are mutated to Ala. MG6 and MG8 are predicted domains within the structure of α2M, which contain the growth factor-binding site and the RBD, respectively.

Cell Culture—The rat pheochromocytoma cell line, PC12, was cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM; high glucose; Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Hyclone, Logan, UT), 5% heat-inactivated horse serum (Omega Scientific Inc., Tarzana, CA), 100 units/ml penicillin, and 100 mg/ml streptomycin at 37 °C. Schwann cells were isolated from the sciatic nerves of 1-day-old Sprague-Dawley rats and further selected from fibroblasts using fibronectin-specific antibody and rabbit complement, as previously described (39). The final preparations consisted of 95–99% Schwann cells, as assessed by immunofluorescence for S100, which is a specific Schwann cell marker. Primary cultures of Schwann cells were maintained in DMEM containing 10% FBS, 100 units/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, 21 μg/ml bovine pituitary extract, and 4 μm forskolin (complete medium) at 37 °C under humidified 5.0% CO2. Schwann cell cultures were passaged no more than four times before conducting experiments.

Murine embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) that are genetically deficient in LRP-1 (MEF-2 cells), and control LRP-1-expressing MEFs (PEA-10 cells) were obtained from the ATCC. PEA-10 and MEF-2 cells were cloned from the same culture, heterozygous for LRP-1 gene disruption, and selected with the LRP-1-selective toxin, Pseudomonas exotoxin A (PEA) (40). MEFs were cultured in DMEM with 10% FBS.

LRP-1 Gene Silencing—A previously characterized rat LRP-1-specific siRNA (L2): CGAGCGACCUCCUAUCUUUUU (41) and pooled non-targeting control (NTC) siRNA were purchased from Dharmacon (Chicago, IL). Primary cultures of Schwann cells (1 × 106) were transfected with LRP-1-specific siRNA or with NTC siRNA (25 nm) by electroporation using the Rat Neuron Nucleofector kit (Amaxa, Gaithersburg, MD) (41). The degree of LRP-1 gene silencing, at the mRNA level, was 88–95%, 48–72-h post-electroporation as determined by quantitative PCR (qPCR) (41). LRP-1 gene silencing was confirmed by immunoblot analysis. Cell signaling experiments were performed 48 h after introduction of siRNAs.

FP6 Activity Assay—The α2M sequence in FP6 includes the LRP-1 recognition site (22). To confirm that FP6 binds to LRP-1, FP6 was radioiodinated using Iodobeads, according to the manufacturer's instructions (Roche Applied Sciences). The specific activity was 2.5 μCi/μg. LRP-1-expressing PEA-10 cells and LRP-1-deficient MEF-2 cells were plated in 24-well plates and cultured until almost confluent. The cells then were washed twice with Earle's Balanced Salts Solution (EBSS) containing 10 mm Hepes, pH 7.4, and 1.0 mg/ml bovine serum albumin (EHB) and equilibrated in the same solution. 125I-FP6 was incubated with the cells for 4 h at 4°C in the presence and absence of non-radiolabeled FP6 (50 nm) or 0.2 μm GST-RAP. The cultures were then washed twice with EHB and once with EBSS. Cell extracts were prepared in 0.1 m NaOH and 1.0% SDS. Cell-associated radioactivity was determined in a PerkinElmer Wizard 1470 Automatic Gamma Counter.

Activation of Akt and ERK/MAP Kinase—Primary cultures of Schwann cells and PC12 cells were plated in 60-mm wells at a density of 2 × 105 cells/well in serum-containing medium and cultured until ∼70% confluent. The cultures then were transferred to serum-free medium and maintained for 5 h (PC12 cells) or for 1 h (Schwann cells) prior to adding candidate stimulants, including α2M peptide-GST fusion proteins, NGF-β, PDGF-BB, or Epo. Incubations with these agents were conducted for 10 min unless otherwise described. The cells then were rinsed twice with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline. Cell extracts were prepared in radioimmune precipitation assay buffer (phosphate-buffered saline with 1% Triton X-100, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, protease inhibitor mixture, and sodium orthovanadate). The protein concentration in cell extracts was determined by bicinchoninic acid assay. An equivalent amount of cellular protein (40 μg) was subjected to 10% SDS-PAGE and electrotransferred to nitrocellulose membranes. The membranes were blocked with 4% nonfat dry milk in 20 mm Tris-HCl, 150 mm NaCl, pH 7.4 with Tween 20 and incubated with primary antibodies. The membranes then were washed and treated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies for 1 h. Immunoblots were developed by enhanced chemiluminescence (Amersham Biosciences).

Neurite Outgrowth—PC12 cells were plated at 2 × 105 cells/well and maintained in serum-containing medium for 24 h. The medium then was replaced with serum-free medium, supplemented with FP6, FP3, NGF-β, FP3+NGF-β, or vehicle. Culturing was continued for 48 h. Axodendritic process formation was assessed by phase contrast microscopy, using a Leica microscope equipped with a DFC 300 digital camera and Open Laboratory software.

RNA Isolation and Real-time qPCR—PC12 cells were plated in 60-mm wells at a density of 2 × 105 cells/well in serum-containing medium and cultured until ∼60% confluent. The cultures then were transferred to serum-free medium for 5 h prior to adding various reagents, including NGF-β, NGF-β plus FP3 (100 nm), FP3 alone (100 nm), FP6 (100 nm), or vehicle. At the indicated times, DNA-free total RNA was extracted using Trizol (Invitrogen) and treated with Turbo DNA-free DNase. cDNA was synthesized using the ProSTAR first-strand RT-PCR kit (Stratagene). Expression of GAP-43 was determined by qPCR using Taqman primers and probes purchased from Applied Biosystems Inc. The one-step program included 2 min at 50 °C, 10 min at 95 °C, followed by 40 cycles of: 95 °C for 15 s; 60 °C for 1 min, using an ABI 7300 instrument. Rat cyclophilin mRNA was measured in each sample as a housekeeping gene (41). Samples without cDNA were analyzed as “no-template” controls. GAP-43 mRNA levels were measured in duplicate, in four separate experiments, and normalized against the Ct value for the housekeeping gene.

RESULTS

Specific Binding of FP6 to LRP-1—FP6 contains the α2M sequence known to mediate binding to LRP-1 (22–24). To confirm that FP6 binds to LRP-1, 125I-labeled FP6 (0.1 nm) was incubated with LRP-1-expressing PEA-10 cells and with LRP-1-deficient MEF-2 cells at 4 °C. Fig. 2A shows that 125I-labeled FP6 bound mainly to the LRP-1-expressing cells. Unlabeled FP6 inhibited binding of 125I-labeled FP6 to PEA-10 cells by >85%, indicating that the majority of the binding was specific; the residual binding observed in the presence of unlabeled FP6 was equivalent to that observed with MEF-2 cells. GST-RAP inhibited the binding of 125I-labeled FP6 to PEA-10 cells by about 85%, confirming that the specific binding was due to LRP-1. GST-RAP did not significantly affect FP6 binding to the LRP-1-deficient MEF-2 cells. These results demonstrate that the LRP-1-binding site is functional in FP6.

FIGURE 2.

Specific binding of FP6 to LRP-1. A, LRP-1-expressing PEA-10 cells and LRP-1-deficient MEF-2 cells were incubated with 5 nm 125I-FP6 for 4 h at 4 °C, in the presence and absence of non-radiolabeled FP6 (50 nm) or 0.2 μm GST-RAP. Cell-associated radioactivity was determined. The results show the mean ± S.D., n = 3. B, FP6 was treated with 0.5 μm trypsin for the indicated times. The trypsin was rapidly inactivated with pNPGB, and the sample subjected to SDS-PAGE and Coomassie Blue staining. The time 0 point was treated with pNPGB prior to trypsin. The lane labeled C shows the initial preparation of FP6. The arrow shows the band at 24 kDa, referred to in the text.

By SDS-PAGE, the apparent mass of FP6 was 53 kDa, as anticipated (Fig. 2B). Treatment of FP6 (20 μm) with 0.5 μm active trypsin revealed a single new major band, migrating with an apparent mass of 24 kDa. This mass is consistent with that predicted for the α2M sequence in FP6 as well as isolated GST. Further degradation of the 24-kDa product(s), to form more rapidly migrating species, was not apparent in the gel, arguing against large areas of disordered structure in FP6, which tend to be susceptible to proteolysis. Intact FP6 and the 24-kDa band, generated by trypsin, were both detected by immunoblot analysis using polyclonal α2M-specific antibody; purified GST was immunonegative (results not shown), confirming that a peptide derived from the sequence of α2M was present in the 24-kDa band.

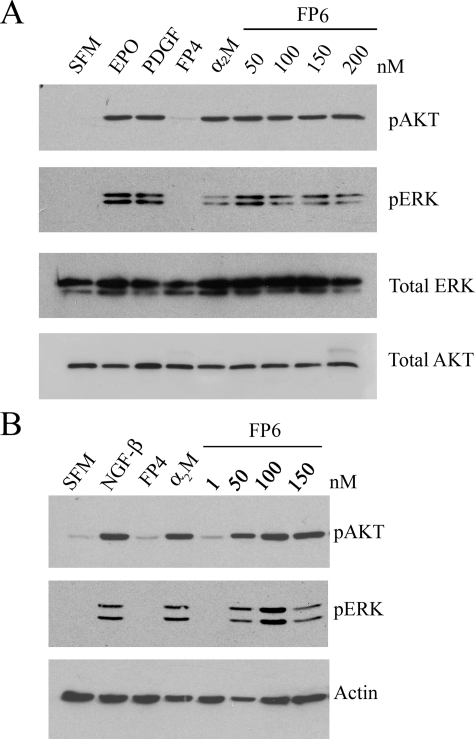

FP6 Activates Cell Signaling in Schwann Cells and PC12 Cells—LRP-1 gene silencing decreases the basal level of Akt activation in Schwann cells, presumably by inhibiting autocrine cell signaling pathways involving endogenously produced LRP-1 ligands (41). In this study, we sought to determine whether α2M activates Akt and ERK/MAP kinase in Schwann cells by binding to LRP-1. Because intact α2M may activate cell signaling by delivering growth factors to the cell, such as PDGF-BB and NGF-β (21), we compared activated α2M(α2M-MA) with FP6, which lacks growth factor-carrier activity (23). As shown in Fig. 3A, FP6 and α2M-MA activated Akt in Schwann cells. Akt also was activated by Epo and PDGF-BB, as anticipated (42). FP4, which does not carry growth factors or bind to LRP-1 and thus represents a negative control, had no effect on Akt activation. Similar results were obtained when we probed for activation of ERK/MAP kinase. Again, FP6, α2M-MA, Epo, and PDGF-BB activated ERK/MAP kinase in Schwann cells, whereas FP4 did not.

FIGURE 3.

FP6 activates Akt and ERK/MAP kinase in Schwann cells and PC12 cells. Schwann cells (A) and PC12 cells (B) were treated with vehicle (serum-free medium, SFM), α2M-MA (50 nm) or with increasing concentrations of FP6 (50–200 nm) for 10 min as indicated. Schwann cells also were treated with PDGF-BB (0.1 μg/ml) or Epo (1 nm) as positive controls and with 50 nm FP4 as a negative control. PC12 cells were treated with NGF-β (50 ng/ml) or 50 nm FP4. Protein extracts were subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblot analysis to detect phosphorylated Akt (pAKT), phosphorylated ERK/MAP kinase (pERK), total ERK/MAP kinase, total Akt, and β-actin. The blots shown are representative of three independent studies.

Next, we examined PC12 cells. These cells are frequently studied as a model system to assess neuronal differentiation in response to NGF-β and other growth factors (43, 44). Fig. 3B shows that FP6 activated Akt and ERK/MAP kinase in PC12 cells. α2M-MA also activated these cell signaling proteins, as did NGF-β, which served as a positive control. FP4 had no effect on Akt or ERK/MAP kinase.

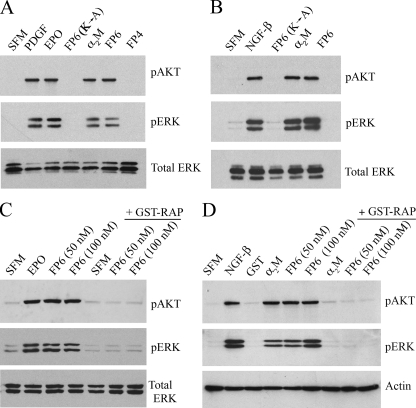

LRP-1 Is Essential for FP6-initiated Cell Signaling—Previous studies suggest that activated α2M may initiate cell signaling independently of LRP-1, by binding to Grp 78 or the NGF receptor, TrkA (16, 32). To test whether LRP-1 is necessary for FP6-initiated cell signaling in Schwann cells and PC12 cells, we applied a number of distinct strategies. First, we assessed cell signaling in response to FP6(K → A). Mutation of two Lys residues in this derivative precludes binding to LRP-1 (23, 24). FP6(K → A) failed to activate Akt and ERK/MAP kinase in Schwann cells (Fig. 4A) and PC12 cells (Fig. 4B). Next, we studied cell signaling in response to FP6 in the presence of the LRP-1 competitive antagonist, GST-RAP. When added to cultures of Schwann cells alone, GST-RAP had no effect on cell signaling (Fig. 4C), confirming results obtained by other investigators (12, 45). However, when added 15 min in advance, GST-RAP blocked cell signaling in response to FP6 in both Schwann cells (Fig. 4C) and PC12 cells (Fig. 4D). GST-RAP also blocked the response to α2M-MA in PC12 cells.

FIGURE 4.

Activation of cell signaling by FP6 requires LRP-1. Schwann cells (A) and PC12 cells (B) were treated with vehicle (serum-free medium, SFM), α2M-MA (50 nm), FP6 (100 nm), FP6(K → A) (100 nm), or FP4 (100 nm) for 10 min. PDGF-BB, Epo, or NGF-β were added as positive controls. Protein extracts were subjected to immunoblot analysis to detect pAKT, pERK, and total ERK/MAP kinase (total ERK). Schwann cells (C) and PC12 cells (D) were treated with FP6 (50 or 100 nm), Epo (1 nm), α2M-MA (50 nm), GST (100 nm), NGF-β (50 ng/ml), or vehicle (SFM) for 10 min. In the last three lanes of each panel, the indicated agent was introduced 15 min after adding GST-RAP (100 nm). Immunoblot analysis was performed to detect pAKT, pERK, total ERK, and β-actin. The blots shown are representative of at least three independent studies.

As a third test of the role of LRP-1 in FP6-initiated cell signaling, we applied LRP-1 gene silencing, which is highly efficient in Schwann cells (41). LRP-1-specific siRNA blocked activation of Akt and ERK/MAP kinase by FP6 in Schwann cells (Fig. 5A). Cell signaling in response to Epo and PDGF-BB were unaffected, demonstrating that the effects of the siRNA on FP6 are specific. In cells that were transfected with NTC siRNA, FP6 activated Akt and ERK/MAP kinase, as did Epo and PDGF-BB (Fig. 5B). Taken together, our results with FP6(K → A), GST-RAP, and LRP-1 gene silencing demonstrate that FP6 activates Akt and ERK/MAP kinase by a mechanism that requires LRP-1.

FIGURE 5.

LRP-1 gene silencing in Schwann cells. Schwann cells were transfected with rat LRP-1-specific siRNA L2 (A) or with pooled NTC siRNA (B). After 48 h, cells were treated with PDGF-BB, Epo, FP6(K → A) (100 nm), or FP6 (100 nm). Protein extracts were subjected to immunoblot analysis to detect pAKT, pERK, and total ERK/MAP kinase. The blots shown are representative of four independent studies.

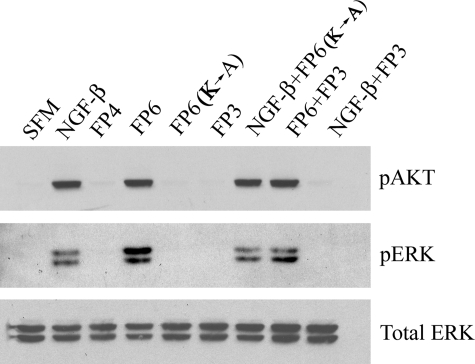

FP3 Inhibits Activation of Akt and ERK/MAP Kinase—Next, we assessed the activity of FP3, which includes the sequence in α2M responsible for binding neurotrophins and other growth factors (20, 21). Availability of the growth factor-binding site in intact α2M is regulated by α2M conformational change (7). Fig. 6 shows that FP3 did not independently regulate the activity of Akt or ERK/MAP kinase in serum-starved PC12 cells. However, FP3 blocked activation of both cell signaling proteins in response to NGF-β. The ability of FP3 to antagonize the response to NGF-β was specific. FP3 had no effect on cell signaling in response to FP6.

FIGURE 6.

FP3 inhibits activation of Akt and ERK/MAP kinase in response to NGF-β but not FP6. PC12 cells were treated with vehicle (serum-free medium, SFM), NGF-β (50 ng/ml), FP4 (100 nm), FP6 (100 nm), FP6(K → A) (100 nm), or FP3 (100 nm) for 10 min. In the last two lanes, FP3 was preincubated with NGF-β or FP6 for 15 min at 37 °C and then added to the cell cultures. Protein extracts were subjected to immunoblot analysis to detect pAKT, pERK, and total ERK/MAP kinase. The blot shown is representative of four independent studies.

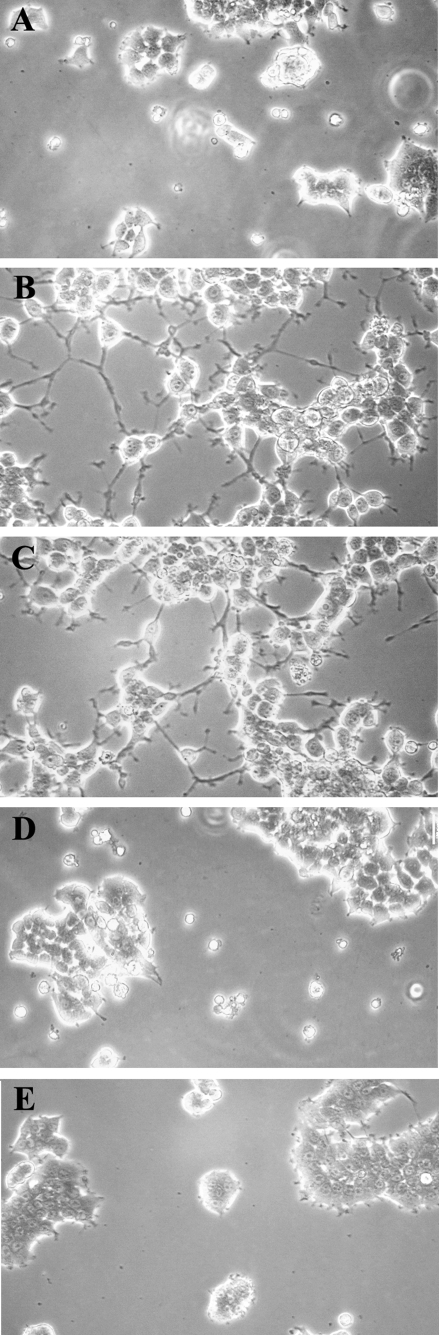

ERK/MAP kinase and Akt have been implicated in neuronal differentiation/neurite extension in PC12 cells (46–49). Thus, we examined the effects of FP3 and FP6 on PC12 cell neurite extension. Fig. 7 shows that FP6 robustly supported neuritic outgrowth in PC12 cells maintained in serum-free medium for 48 h. A comparable response was detected in cells that were treated with NGF-β. FP3 did not independently regulate neurite outgrowth but instead, entirely blocked the response to NGF-β. Thus, the effects of FP3 and FP6 on neurite outgrowth paralleled their effects on cell signaling in the PC12 cell culture model system.

FIGURE 7.

FP3 and FP6 have opposite effects on PC12 cell neuritogenesis. PC12 cells were cultured for 48 h in serum-free medium alone (A), or supplemented with 100 nm FP6 (B), 50 ng/ml NGF-β (C), 100 nm FP3 (D), or NGF-β+FP3 (E). Axodendritic process formation was assessed by phase contrast microscopy. Representative fields are shown (n = 3).

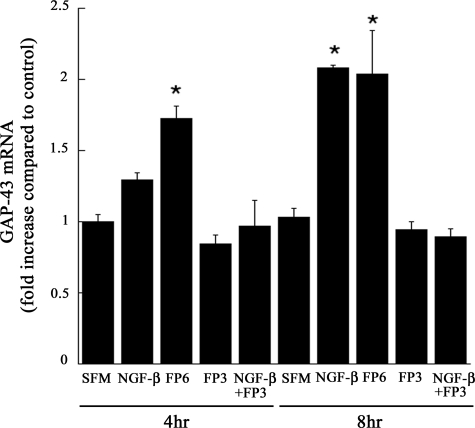

Our neurite extension results were supported by separate experiments in which we examined expression of mRNA for GAP-43, a neuronal differentiation marker (34). Fig. 8 shows that FP6 significantly increased GAP-43 expression at 4 and 8 h (p < 0.05). The magnitude of the response was as great or greater than that observed with NGF-β. FP3 had no independent effect on GAP-43 expression, but instead completely blocked GAP-43 mRNA expression in response to NGF-β.

FIGURE 8.

FP3 and FP6 differentially regulate expression of GAP-43. PC12 cells were cultured in serum-free medium for 5 h and then treated with vehicle (SFM), NGF-β (50 ng/ml), NGF-β + FP3 (100 nm), FP3 (100 nm), or FP6 (100 nm). Incubations were conducted for 4 or 8 h. Total RNA was isolated. GAP-43 mRNA expression was determined by qPCR (mean ± S.D., n = 4; *, p < 0.05, one-way analysis of variance with Tukey's posthoc for each time period).

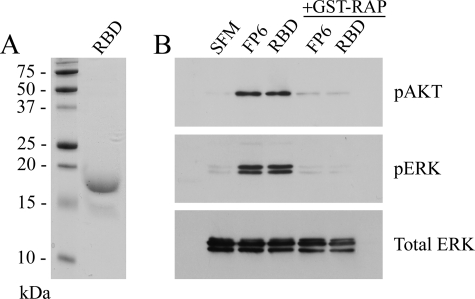

The 18-kDa α2M RBD and FP6 Activate Cell Signaling Equivalently—GST fusion proteins may be expressed as dimers (50). For FP6, dimeric structure might allow cell signaling to occur by cross-linking of LRP-1 to a co-receptor such as Grp 78 or by cross-linking of LRP-1 into homodimers. To test whether the α2M RBD activates cell signaling as a monomer, we isolated the 18-kDa RBD from plasma-purified α2M (4). Fig. 9A shows SDS-PAGE analysis of the final, purified product. The 18-kDa RBD activated both Akt and ERK/MAP kinase in PC12 cells, mimicking the results obtained with FP6 (Fig. 9B). GST-RAP blocked the response to the 18-kDa RBD, indicating an essential role for LRP-1.

FIGURE 9.

FP6 and the RBD from purified α2M activate cell signaling equivalently. A, the 18-kDa RBD, isolated from α2M-MA by proteolysis and purified by chromatography, was subjected to SDS-PAGE and stained with Coomassie Blue. B, PC12 cells were cultured in SFM or treated with FP6 (50 nm) or the 18-kDa RBD from α2M-MA (50 nm) for 10 min. In some lanes, the cells were pretreated with GST-RAP (100 nm) for 15 min, as indicated. Protein extracts were subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblot analysis to detect pAKT, pERK, and total ERK/MAP kinase. The blot shown is representative of triplicate independent experiments.

DISCUSSION

Although a number of reports indicate that activated α2M initiates cell-signaling, questions remain regarding this activity. First, in some cell culture model systems, LRP-1 does not appear to be necessary for the response (16, 32). Furthermore, the relationship between α2M-initiated cell signaling, and its ability to carry growth factors has not been addressed. In this study, we show that the isolated LRP-1-binding domain of α2M, expressed as a GST fusion protein or isolated from the plasma protein, robustly activates Akt and ERK/MAP kinase in Schwann cells and PC12 cells. We provide three separate lines of evidence indicating that LRP-1 is necessary. First, the response was blocked by GST-RAP. LRP-1 gene silencing neutralized the response to FP6. Finally, mutating two amino acids in FP6, which are known to function in LRP-1 binding, eliminated the ability of FP6 to trigger cell signaling. The mutation in FP6(K → A) also may block binding to Grp 78 (24); however, the three lines of evidence only may be interpreted as indicating an essential role for LRP-1.

The ability of FP6 and the 18-kDa RBD of α2M to trigger robust cell signaling to Akt and ERK/MAP kinase by binding to LRP-1 justifies clustering α2M with other LRP-1 ligands, such as tissue-type plasminogen activator and apolipoprotein E, which also activate cell signaling by binding LRP-1 (45, 51). The consequences of these LRP-1-initiated cell signaling events remain to be fully elucidated. We previously demonstrated that in Schwann cells, regulation of the basal level of activated Akt by LRP-1 may by important for Schwann cell survival (41). In peripheral nerve injury, Schwann cell survival is essential for nerve regeneration (42). In this study, we assessed neurite formation in PC12 cells. FP6 robustly promoted neurite outgrowth and increased expression of GAP-43, matching the magnitude of the response observed with NGF-β. This result was consistent with the demonstrated ability of FP6 to activate ERK/MAP kinase and Akt in PC12 cells. These cell signaling factors have been linked to neuronal differentiation (46–49). Because FP6 functions via an LRP-1-dependent mechanism, our results are consistent with a model in which LRP-1-initiated cell signaling may promote neuronal differentiation.

Availability of the LRP-1 recognition site in α2M is dependent on the α2M conformation (1, 6). In the native form of α2M, which circulates in the plasma, the LRP-1 recognition sequence is completely cryptic. In the activated conformation, the LRP-1 recognition sequence is fully available. Chemically modified forms of α2M, which have undergone partial conformational change, bind to LRP-1 but with decreased efficiency compared with α2M-MA (6). Thus, as the structure of α2M moves toward the fully transformed state, the LRP-1 recognition site is increasingly exposed and available. The effects of α2M conformational change on availability of the growth factor-binding site are more complicated. The growth factor-binding site is partially available in the native form of α2M (7), accounting for the function of native α2M as the principal carrier of TGF-β1 in the plasma (11, 53). Fully activated α2M binds most growth factors with increased affinity (7, 8); however, there is evidence that the growth factor binding site may be most available in intermediate α2M conformations (52, 54, 55). Thus, penetration of the activities associated with FP3 and FP6 may vary asynchronously in α2M conformational change.

In the studies presented here, FP3 demonstrated activities that oppose those of FP6. In the presence of NGF-β, FP3 inhibited activation of Akt and ERK/MAP kinase, blocked PC12 cell neurite outgrowth, and inhibited expression of GAP-43. We propose that the effects of FP3 on cell physiology, demonstrated here, are due to the previously demonstrated ability of FP3 to bind NGF-β (8). FP3 did not antagonize the activity of FP6. In the presence of FP3, FP6-induced cell-signaling to Akt and ERK/MAP kinase was unchanged. We think this result explains why intact α2M-MA activates Akt and ERK/MAP kinase similarly to FP6. In the intact protein, in the absence of concomitantly added growth factors, the function of FP6 is dominant. However, our model predicts that if activated α2M and NGF-β were added to cultures of Schwann cells or PC12 cells together, the effects would not be additive because of the inhibitory effects of the FP3 region of α2M on NGF-β activity. The FP3 region within full-length-activated α2M also may regulate growth factors produced endogenously by cells.

Although native α2M binds NGF-β with lower affinity than activated α2M, according to our model, because the LRP-1 recognition site is entirely cryptic in native α2M, the FP3 site is dominant and the overall effects of intact, native α2M are expected to mimic FP3. Similarly, the FP3 region may dominate in α2M conformational intermediates, which are reported to exist in vivo (36, 54). Understanding the balance between functional sites contained within different domains of α2M is a goal for future investigation.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants R01 NS-054671, R01 HL-60551, and R01 NS-057456. The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement”in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: α2M, α2-macroglobulin; LRP-1, low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein; PDGF-BB, platelet-derived growth factor-BB; NGF-β, nerve growth factor-β; GST, glutathione S-transferase; FP, fusion protein; GAP-43, growth-associated protein; α2M-MA, α2-macroglobulin that is methylamine-activated; RAP, receptor-associated protein; Akt, protein kinase B; ERK/MAP, extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase/mitogen-activated protein; FP6(K → A), fusion protein-6 mutated to Ala at Lys1370 and Lys1374; DMEM, Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium; FBS, fetal bovine serum; MEFs, murine embryonic fibroblasts; PEA, Pseudomonas exotoxin A; NTC, non-targeting control; EBSS, Earle's Balanced Salt solution; RBD, recognition binding domain; qPCR, quantitative PCR.

References

- 1.Sottrup-Jensen, L., Sand, O., Kristensen, L., and Fey, G. H. (1989) J. Biol. Chem. 264 15781–15789 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barrett, A. J., Brown, M. A., and Sayers, C. A. (1979) Biochem. J. 181 401–418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gonias, S. L., Reynolds, J. A., and Pizzo, S. V. (1982) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 705 306–314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sottrup-Jensen, L., Gliemann, J., and Van Leuven, F. (1986) FEBS Lett. 205 20–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huang, W., Dolmer, K., Liao, X., and Gettins, P. G. (1998) Protein Sci. 7 2602–2612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gonias, S. L., and Pizzo, S. V. (1983) Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 421 457–471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crookston, K. P., Webb, D. J., Wolf, B. B., and Gonias, S. L. (1994) J. Biol. Chem. 269 1533–1540 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wolf, B. B., and Gonias, S. L. (1994) Biochemistry 33 11270–11277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weaver, A. M., Owens, G. K., and Gonias, S. L. (1995) J. Biol. Chem. 270 30741–30748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lysiak, J. J., Hussaini, I. M., Webb, D. J., Glass, W. F., Allietta, M., and Gonias, S. L. (1995) J. Biol. Chem. 270 21919–21927 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Philip, A., and O'Connor-McCourt, M. D. (1991) J. Biol. Chem. 266 22290–22296 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bacskai, B. J., Xia, M. Q., Strickland, D. K., Rebeck, G. W., and Hyman, B. T. (2000) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97 11551–11556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Qiu, Z., Hyman, B. T., and Rebeck, G. W. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279 34948–34956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bonacci, G. R., Caceres, L. C., Sanchez, M. C., and Chiabrando, G. A. (2007) Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 460 100–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Padmasekar, M., Nandigama, R., Wartenberg, M., Schluter, K. D., and Sauer, H. (2007) Cardiovasc. Res. 75 118–128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Misar, U. K., Gonzalez-Gronow, M., Gawdi, G., Hart, J. P., Johnson, C. E., and Pizzo, S. V. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 44 42082–42087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Misra, U. K., Deedwania, R., and Pizzo, S. V. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281 13694–13707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.LaMarre, J., Hayes, M. A., Wollenberg, G. K., Hussaini, I., Hall, S. W., and Gonias, S. L. (1991) J. Clin. Investig. 87 39–44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Doan, N., and Gettins, P. G. (2007) Biochem. J. 407 23–30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Webb, D. J., Wen, J., Karns, L. R., Kurilla, M. G., and Gonias, S. L. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273 13339–13346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gonias, S. L., Carmichael, A., Mettenburg, J. M., Roadcap, D. W., Irvin, W. P., and Webb, D. J. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275 5826–5831 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mettenburg, J. M., Webb, D. J., and Gonias, S. L. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277 13338–13345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nielsen, K. L., Holtet, T. L., Etzerodt, M., Moestrup, S. K., Gliemann, J., Sottrup-Jensen, L., and Thogersen, H. C. (1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271 12909–12912 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Howard, G. C., Yamaguchi, Y., Misra, U. K., Gawdi, G., Nelsen, A., De-Camp, D. L., and Pizzo, S. V. (1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271 14105–14111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Arandjelovic, S., Van Sant, C. L., and Gonias, S. L. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281 17061–17068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Arandjelovic, S., Hall, B. D., and Gonias, S. L. (2005) Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 438 29–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Umans, L., Serneels, L., Overbergh, L., Lorent, K., Van Leuven, F., and Van den Berghe, H. (1995) J. Biol. Chem. 270 19778–19785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hochepied, T., Van Leuven, F., and Libert, C. (2002) Eur. Cytokine Netw. 13 86–91 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gourine, A. V., Gourine, V. N., Tesfaigzi, Y., Caluwaerts, N., Van Leuven, F., and Kluger, M. J. (2002) Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 283 R218–R226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Esadeg, S., He, H., Pijnenborg, R., Van Leuven, F., and Croy, B. A. (2003) Placenta 24 912–921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Waghabi, M. C., Coutinho, C. M., Soeiro, M. N., Pereira, M. C., Feige, J. J., Keramidas, M., Cosson, A., Minoprio, P., Van Leuven, F., and Araujo-Jorge, T. C. (2002) Infect. Immun. 70 5115–5123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee, P. G., and Koo, P. H. (2000) J. Neurochem. 74 81–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chiabrando, G. A., Sanchez, M. C., Skornicka, E. L., and Koo, P. H. (2002) J. Neurosci. Res. 70 57–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Karns, L. R., Ng, S. C., Freeman, J. A., and Fishman, M. C. (1987) Science 236 597–600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Imber, M. J., and Pizzo, S. V. (1981) J. Biol. Chem. 256 8134–8139 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nelles, L. P., Hall, P. K., and Roberts, R. C. (1980) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 623 46–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Webb, D. J., Hussaini, I. M., Weaver, A. M., Atkins, T. L., Chu, C. T., Pizzo, S. V., Owens, G. K., and Gonias, S. L. (1995) Eur. J. Biochem. 234 714–722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Strickland, D. K., Gonias, S. L., and Argraves, W. S. (2002) Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 13 66–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Campana, W. M., Hiraiwa, M., and O'Brien, J. S. (1998) FASEB J. 12 307–314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Willnow, T. E., and Herz, J. (1994) J. Cell Sci. 107 719–726 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Campana, W. M., Li, X., Dragojlovic, N., Janes, J., Gaultier, A., and Gonias, S. L. (2006) J. Neurosci. 26 11197–11207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Campana, W. M. (2007) Brain Behav. Immun. 21 522–527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Greene, L. A., and Tischler, A. S. (1976) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 73 2424–2428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tyson, D. R., Larkin, S., Hamai, Y., and Bradshaw, R. A. (2003) Int. J. Dev. Neurosci. 21 63–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hu, K., Yang, J., Tanaka, S., Gonias, S. L., Mars, W. M., and Liu, Y. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281 2120–2127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Leppa, S., Saffrich, R., Ansorge, W., and Bohmann, D. (1998) EMBO J. 17 4404–4413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Robinson, M. J., Stippec, S. A., Goldsmith, E., White, M. A., and Cobb, M. H. (1998) Curr. Biol. 8 1141–1150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Eriksson, M., Taskinen, M., and Leppa, S. (2007) J. Cell Physiol. 210 538–548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kim, Y., Seger, R., Suresh Babu, C. V., Hwang, S. Y., and Yoo, Y. S. (2004) Mol. Cell 18 353–359 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rufer, A. C., Thiebach, L., Baer, K., Klein, H. W., and Hennig, M. (2005) Acta Crystallogr. F61 263–265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hayashi, H., Campenot, R. B., Vance, D. E., and Vance, J. E. (2007) J. Neurosci. 27 1933–1941 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Webb, D. J., and Gonias, S. L. (1998) Lab. Investig. 78 939–948 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.O'Connor-McCourt, M. D., and Wakefield, L. M. (1987) J. Biol. Chem. 262 14090–14099 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.LaMarre, J., Wollenberg, G. K., Gonias, S. L., and Hayes, M. A. (1991) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1091 197–204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Webb, D. J., and Gonias, S. L. (1997) FEBS Lett. 410 249–253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]