Abstract

The agonist binding site of ATP-gated P2X receptors is distinct from other ATP-binding proteins. Mutagenesis on P2X1 receptors of conserved residues in mammalian P2X receptors has established the paradigm that three lysine residues, as well as FT and NFR motifs, play an important role in mediating ATP action. In this study we have determined whether cysteine substitution mutations of equivalent residues in P2X2 and P2X4 receptors have similar effects and if these mutant receptors can be regulated by charged methanethiosulfonate (MTS) compounds. All the mutants (except the P2X2 K69C and K71C that were expressed, but non-functional) showed a significant decrease in ATP potency, with >300-fold decreases for mutants of the conserved asparagine, arginine, and lysine residues close to the end of the extracellular loop. MTS reagents had no effect at the phenylalanine of the FT motif, in contrast, cysteine mutation of the threonine was sensitive to MTS reagents and suggested a role of this residue in ATP action. The lysine-substituted receptors were sensitive to the charge of the MTS reagent consistent with the importance of positive charge at this position for coordination of the negatively charged phosphate of ATP. At the NFR motif the asparagine and arginine residues were sensitive to MTS reagents, whereas the phenylalanine was either unaffected or showed only a small decrease. These results support a common site of ATP action at P2X receptors and suggest that non-conserved residues also play a regulatory role in agonist action.

P2X receptors for ATP comprise a distinct family of ligandgated ion channels, with two transmembrane domains, intracellular amino and carboxyl termini and a large extracellular ligand binding loop. Seven P2X receptor genes have been identified (P2X1–7) and the subunits form functional homo- and heterotrimeric ion channels with a variety of phenotypes (1). ATP is released from neurons, in response to shear stress, as well as from damaged cells. P2X receptors have been shown to be involved in a wide range of physiological roles including blood clotting (2), sensory perception (including pain (3–5), bladder voiding (6), and taste (7)), as well as bone formation (8). As the receptors provide novel drug targets for a range of diseases (9) an understanding of the agonist binding site would be useful for rational drug design. However, it is clear that common ATP binding sequences, e.g. the Walker motif (10), are not present in P2X receptors. In the absence of a crystal structure a site-directed mutagenesis approach has been used to gain insight into amino acids important in mediating the actions of ATP at P2X receptors.

We have used the human P2X1 receptor and alanine mutagenesis of conserved residues in the extracellular loop (Fig. 1) to propose a model of the ATP binding site (reviewed in Refs. 11 and 12). Cysteine substitution mutagenesis and charged methanethiosulfonate (MTS)3 compounds have been useful in investigating a variety of ion channels including the pore region (13, 14) as well as residues involved in ATP action/sensitivity at P2X receptors (15, 16). We have used this approach to study the contribution of the 44 amino acids before the second transmembrane domain to ATP action at the P2X1 receptor (16). For example, we have shown that for the mutant K309C, ATP potency and binding of radiolabeled 2-azido-ATP is reduced. The K309C mutant was also accessible to MTS reagents. When positively charged MTSEA ((2-aminoethyl)-methanethiosulfonate hydrobromide) modifies a free cysteine residue it produces a positively charged side chain of similar size to lysine (17). MTSEA application rescued ATP potency at K309C supporting that the charged lysine at this position plays a role in coordinating the binding of the negatively charged phosphate tail of ATP (16). In addition our work with alanine and cysteine mutants has also identified residues that are unlikely to play a major role in ATP action (Fig. 1). Taken together our work has given rise to a model of the ATP binding site with the phosphate tail of ATP bound to residues Lys68 and Lys309, and the aromatic ring sandwiched between residues Phe185-Thr186 and Asn290-Phe291-Arg292. This is supported by a recent study on the P2X1 receptor showing that substituted cysteine mutants of residues Lys68 and Phe291 can form an intersubunit disulfide bond and this is inhibited in the presence of ATP (18). The model is also corroborated by some mutagenesis studies from P2X2 and P2X4 receptors (15, 19). However, an alternative model of ATP action at the P2X4 receptor based on a similarity in predicted structure to the tRNA synthetases has also been suggested (20). In this study to determine whether P2X receptor subunits share a core common mode of ATP action we tested at P2X2 and P2X4 receptors whether cysteine mutagenesis of the residues corresponding to those proposed in the P2X1 receptor model have any effects on ATP potency or the action of MTS reagents.

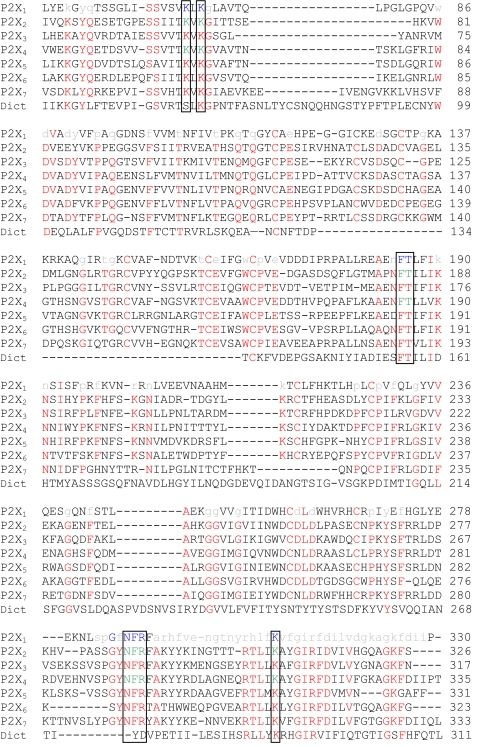

FIGURE 1.

Sequence line-up of the extracellular domain of human P2X1–7 receptors and the Dictostelium discoideum (Dict) P2X receptor (37). Residues conserved in at least 5 of the human P2X receptors are shown in red. Alanine or cysteine mutants of the P2X1 receptor that have no or less than a 10-fold change in ATP potency are shown in lowercase gray (12, 16). P2X1 receptor mutants with a greater than 10-fold decrease in ATP potency are shown in blue. Residues that have been suggested to be important in ATP action are boxed (12, 16). Cysteine mutants of P2X2 and P2X4 receptors characterized in this paper are shown in green.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Site-directed Mutagenesis—Cysteine point mutations for residues were introduced via the QuikChange™ mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) using a human P2X2 receptor or rat P2X4-myc (Y378A) plasmid as the template. Human P2X2 receptor plasmid (gift of Dr. Andrew Powell, GlaxoSmithKline, United Kingdom) contained the sequence of the P2X2a isoform (Q9UBL9) with the NH2-terminal variant MAAAQPKYPAGATA → MV as described.4 For the rat P2X4-myc (gift of Dr. Francois Rassendren, CNRS, Montpellier, France), the mutant Y378A was created and used as the template for more stable currents (21). Production of the correct mutations and absence of coding errors in the P2X2 and P2X4 mutant constructs was verified by DNA sequencing (Automated ABI Sequencing Service, University of Leicester).

Expression in Xenopus laevis Oocytes—Wild type and mutant constructs were transcribed to produce sense strand cRNA (mMessage mMachine™, Ambion, TX) as described previously (22). Manually defoliculated stage V X. laevis oocytes were injected with 50 nl (50 ng) of cRNA using an Inject+Matic microinjector (J. Alejandro Gaby, Genéva, Switzerland) and stored at 18 °C in ND96 buffer (96 mm NaCl, 2 mm KCl, 1.8 mm CaCl2, 1 mm MgCl2, 5 mm sodium pyruvate, 5 mm HEPES, pH 7.6). Media was changed daily prior to recording 3–7 days later.

Electrophysiological Recordings—Two-electrode voltage clamp recordings (at a holding potential of –60 mV) were carried out on cRNA-injected oocytes using a GeneClamp 500B amplifier with a Digidata 1322 analog to digital converter and pClamp 8.2 acquisition software (Axon Instruments) as previously described (22). Native oocyte calcium-activated chloride currents in response to P2X receptor stimulation were reduced by replacing 1.8 mm CaCl2 with 1.8 mm BaCl2 in the ND96 bath solution. ATP (magnesium salt, Sigma) was applied via a U-tube perfusion system. ATP (0.1 μm to 10 mm) was applied at 5-min intervals, using this regime reproducible ATP-evoked responses were recorded. Individual concentration-response curves were fitted with the Hill equation: Y = [(X)H × M]/[(X)H + (EC50)H], where Y is response, X is agonist concentration, H is the Hill coefficient, M is maximum response, and EC50 is the concentration of agonist evoking 50% of the maximum response. pEC50 is the –log10 of the EC50 value. Mutants that had considerably shifted ATP potency were tested with ATP concentrations up to 10 mm. For the calculation of EC50 values individual concentration-response curves were generated for each experiment and statistical analysis carried out on the pEC50 data generated. In the figures, concentration-response curves are fitted to the mean normalized data.

Characterization of the Effects of Methanethiosulfonate Compounds—To study the effect of MTS compounds on ATP activation at wild type and cysteine mutants, ATP (∼EC50 concentration) was applied and either MTSEA or sodium (2-sulfonatoethyl)methanethiosulfonate (MTSES) (Toronto Research Chemicals, Toronto, Canada) were bath-perfused (for at least 5 min; the recovery time required between application to see reproducible responses) prior to coapplication with ATP via the U-tube as described previously (15, 16). MTS reagents (1 mm) were made in ND96 solution immediately prior to use. MTS reagents were applied for 10 min with the maximal, or near maximal response seen after 5 min. The effects of the MTS reagents on the P2X2 receptor mutants were the same following washout of the compounds showing that they irreversibly modified the receptors.

The effects of the MTS compounds on the mutant P2X4 receptors were reversible following a 5–10 min washout. The P2X4 receptor has been shown to be subject to extensive constitutive and agonist induced trafficking (23) even for the Y378A mutant used in this study (21, 24). To determine whether longer incubations could be used to irreversibly modify P2X4 mutant receptors we treated the oocytes for 3 h in the presence of MTSES (1 mm) and 3.2 units/ml of apyrase to break down any endogenous ATP, or just apyrase. This longer incubation was aimed to modify more of the pool of P2X4 receptors. This was followed by washing and subsequent testing of responses to an EC50 concentration of ATP (in the absence of MTSES). This treatment had no effect on the amplitude of WT P2X4 receptor currents, however, reductions of the mutants were equivalent to those where MTSES was present during the recordings demonstrating that any changes in properties for the mutant receptors result from irreversible modification of introduced cysteine residues and that cysteine residues were available in the resting un-liganded state of the receptor. MTS reagents have a reasonably short half-life and this suggests that the 1 mm concentration used is supramaximal and there was still sufficient reagent present during the 3-h incubation to irreversibly modify the receptors. These results suggest that the reversal of MTS effects following washout of short applications is likely to result from trafficking of un-modified receptors to the cell surface and longer incubations are required to irreversibly modify the whole pool of P2X4 mutant receptors. We have therefore presented data for effects on an EC50 concentration of ATP during the presence of the MTS reagents as this allows us to analyze data from the same oocyte before and during application of the reagents.

The effects of MTS reagents on the concentration responses to ATP for P2X2 receptors were investigated following washout of MTSEA (applied at 1 mm for 10 min in the absence of agonist), there was no effect on WT responses. For P2X4 receptors the effects of MTSEA on concentration responses were investigated by application of ATP following incubating the oocytes for 1 h in MTSEA (1 mm) and washout of MTSEA. ATP concentrations were applied via the U-tube with ND96 bathing solution (no MTS reagents present).

Western Blotting—Expression levels of wild type and mutant receptors were estimated by Western blot analysis of total cellular protein and cell surface proteins. Total cellular protein samples were prepared from oocytes injected with wild type or mutant receptor cRNA homogenized in buffer H (100 mm NaCl, 20 mm Tris-Cl, pH 7.4, 1% Triton X-100, and 10 μl/ml protease inhibitor mixture) at 20 μl/oocyte. Sulfo-NHS-LC-Biotin (Pierce) labels cell surface proteins by reacting with primary amines and was used to estimate the level of wild type or mutant receptor trafficked to the cell surface membrane. Sulfo-NHS-LC-biotin is impermeable to the cell membrane and can only biotinylate proteins available at the cell surface. Oocytes injected with wild type or mutant receptor cRNA were treated with sulfo-NHS-LC-biotin (0.5 mg/ml) in ND96 for 30 min and washed with ND96. Oocytes were homogenized in buffer H, and the spin-cleared supernatant was mixed with streptavidin-agarose beads (Sigma) treated as described previously (25). All samples were mixed with SDS sample buffer and heated to 95 °C for 5 min prior to loading. Samples were run on a 10% SDS-PAGE gel, transferred to nitrocellulose, and screened for immunoreactivity for the anti-P2X2 or P2X4 antibody (1:500) (Alomone, Israel).

Analysis—All data are shown as mean ± S.E. Significant differences between WT and mutant maximum current amplitudes, agonist potency, and MTS reagent modification were calculated by one-way analysis of variance followed by Dunnett's test for comparisons of individual mutants against control using the GraphPad Prism package. Differences in mutant concentration response curves for individual mutants, on treatment with MTSEA, were tested with Student's t test. n corresponds to the number of oocytes tested for electrophysiological data.

RESULTS

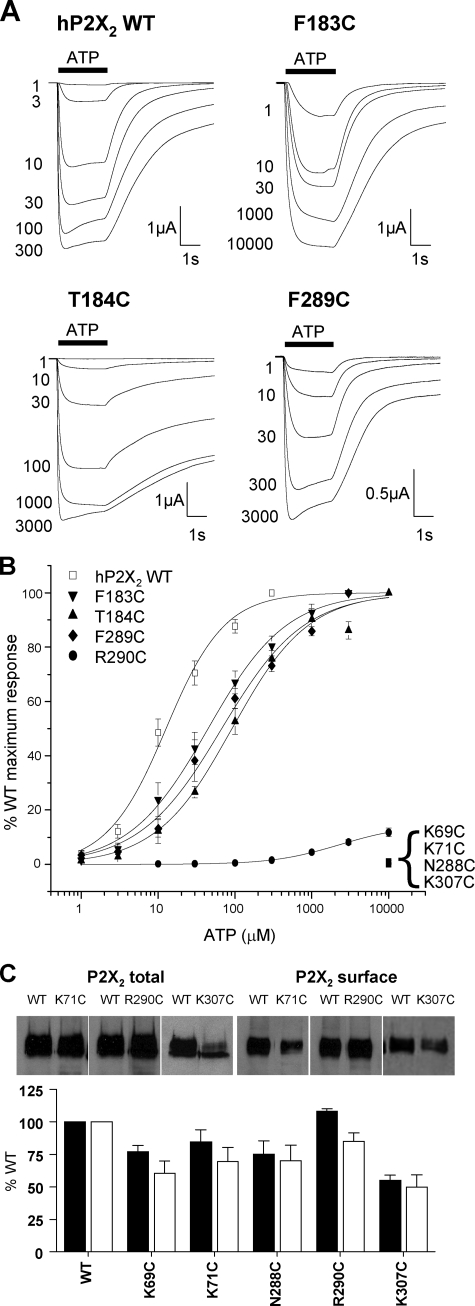

Effects of Cysteine Mutants on ATP Responses at P2X2 Receptors—At WT human P2X2 receptors ATP evoked concentration-dependent inward currents with an EC50 of ∼13 μm (Fig. 2 and Table 1) similar to that reported previously for this receptor (14, 15, 26). Robust currents were also recorded for F183C, T184C, and F289C mutants, however, they showed a modest 4–10-fold decrease in ATP potency (Fig. 2, Table 1). The peak amplitude of currents to a maximal concentration of ATP (10 mm) were reduced by ∼90% for the mutant R290C and for this receptor the amplitude of responses continued to increase between 3 and 10 mm indicating the EC50 is >3 mm ATP. At mutants N288C and K307C 10 mm ATP evoked very small currents suggesting that the EC50 for these receptors is >3 mm. No currents were recorded in response to 10 mm ATP for mutants K69C and K71C. Analysis of the expression of both total and surface levels of P2X2 WT and mutant receptors with reduced peak current amplitudes showed that there was at most an ∼50% reduction in surface expression (K307C), predicting a halving in peak current amplitude, however, there was a >97% reduction in amplitudes for K69C, K71C, and N288C. This indicates that any reductions in current amplitude compared with WT were predominantly due to an effect on channel properties and not trafficking to the cell surface. Overall these results are consistent with those from similar mutants for the P2X1 receptor (12).

FIGURE 2.

Effect of point cysteine P2X2 mutations on ATP potency. ATP potency was tested on WT and P2X2 receptor mutants expressed in oocytes by two-electrode voltage clamp (holding potential =–60 mV). A, trace data representative of currents observed for wild type and mutant receptors in response to ATP applications (indicated by the bar, concentrations in micromolar) at 5-min intervals. B, concentration-response curves to ATP for WT and mutants K69C, K71C, F183C, T184C, N288C, F289C, R290C, and K307C. K69C, K71C, N288C, and K307C with reduced peak currents in response to a maximal concentration of ATP, are expressed as a percentage of the amplitude of the WT maximum response, whereas all others are expressed as a percentage of their own maximum response (n = 3–10). C, Western blots of total and surface expression levels of WT and mutant P2X2 receptors with reduced peak current amplitudes. Lower panel shows densitometric analysis of the blots expressed as % of WT levels.

TABLE 1.

Summary of the effects of cysteine substitution on P2X2 and P2X4

Peak current values taken on 1st application of a maximal concentration of ATP (a saturating concentration 300 μm to 10 mm). pEC50 values shown as calculated from experimental data. pEC50 is –log10 of the EC50. MTS data (effect of ATP applied in the presence of MTS reagent) calculated as a percentage of the control (effect of ATP applied in the absence of MTS reagent) which was set as 100%.

| nA (max) | EC50 | pEC50 | MTSEA | MTSES | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human P2X2 | |||||

| WT | 4465 ± 477 | 13 μm | 4.89 ± 0.1 | 127 ± 2% | 101 ± 3% |

| K69C | NFa | NF | NF | No effect | No effect |

| K71C | NF | NF | NF | No effect | No effect |

| F183C | 4661 ± 1209 | 40 μm | 4.40 ± 0.1b | 128 ± 2% | 96 ± 1% |

| T184C | 4515 ± 1402 | 117 μm | 3.93 ± 0.1c | 195 ± 11%d | 20 ± 3%c |

| N288C | 13 ± 2b | >3 mm | <2.52 | 22 ± 5%b | 21 ± 3%c |

| F289C | 2279 ± 583 | 64 μm | 4.19 ± 0.1c | 123 ± 11% | 78 ± 11%d |

| R290C | 525 ± 70d | >3 mm | <2.52 | 1237 ± 249%c | 27 ± 7%c |

| K307C | 49 ± 20c | >3 mm | <2.52 | 27500 ± 6660%c | 15 ± 1%c |

| Rat P2X4-myc (Y378A) | |||||

| WT | 2513 ± 187 | 13 μm | 4.89 ± 0.02 | 103 ± 11% | 108 ± 6% |

| K67C | 66 ± 21d | NDe | ND | 2076 ± 485%c | 15 ± 4%c |

| K69C | 821 ± 146 | >3 mm | <2.52 | 350 ± 50%c | 1 ± 1%c |

| F185C | 587 ± 224 | 265 μm | 3.58 ± 0.07c | 93 ± 7% | 95 ± 2% |

| T186C | 1706 ± 425 | 650 μm | 3.19 ± 0.04c | 35 ± 6%d | 8 ± 3%c |

| N293C | 521 ± 164 | >3 mm | <2.52 | 6 ± 1%c | 2 ± 1c |

NF, nonfunctional.

p < 0.01, n = 3-18.

p < 0.001, n = 3-18.

p < 0.05, n = 3-18.

ND, not determined.

Effects of MTS Reagents on Cysteine Mutant P2X2 Receptors—At P2X receptors the 10 conserved cysteine residues in the extracellular domain are thought to form five intrasubunit disulfide bonds (25, 27). The substituted cysteine accessibility method has been used to look at the contribution of introduced cysteine mutants to receptor function, where modification of properties following application of MTS reagents indicates that the introduced cysteine residue is accessible in the aqueous environment and may play an important role in receptor function (28). Previously, charged MTS reagents (positively charged MTSEA and negatively charged sodium MTSES), have been used to probe residues involved in ATP action at P2X receptors (15, 16) as they may interact with the negative charge of the phosphate tail of ATP or magnesium complexed with ATP in physiological solutions giving rise to localized positive charge.

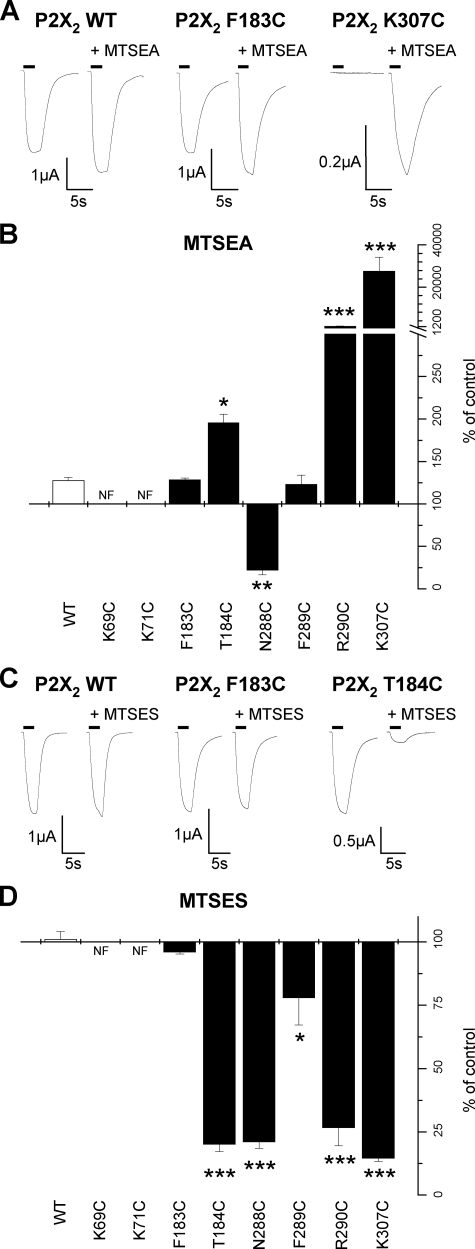

At WT P2X2 receptors MTSEA (1 mm) produced a small increase (128 ± 3% of control) in the response to an EC50 concentration of ATP (Table 1, Fig. 3) as reported previously for this receptor (13, 14). MTSEA had no effect on the potency of ATP and current amplitudes returned to control levels on washout. MTSEA had a similar effect at F183C and F289C mutant P2X2 receptors (Table 1, Fig. 3). At T184C there was an increase in potentiation to 195 ± 11% of control, however, on washout this was reduced to 141 ± 11% of control indicating that it results from a combination of the reversible effect seen for WT and an additional irreversible modification. R290C and K307C MTSEA produced a significantly larger increase in the response to an EC50 concentration of ATP (Table 1, Fig. 3) that was sustained on washout indicating that it results from irreversible modification of the introduced cysteine.

FIGURE 3.

Effect of MTS compounds on ATP responses of P2X2 cysteine mutants. A, trace data representative of currents observed before and during the addition of MTSEA (1 mm). ATP application (EC50 concentration) is indicated by the bar. MTSEA reagent was bath applied 5 min prior to U-tube ATP coapplication with MTSEA. B, graph representing the effect of MTSEA on the P2X2 WT and mutant receptors (n = 3–6). C, trace data representative of currents observed with the addition of MTSES (1 mm). ATP application (EC50 concentration) is indicated by the bar. MTSES reagent applied in a similar manner to MTSEA traces are shown for a given oocyte before and during MTSES application. D, graph representing the effect of MTSES on the P2X2 WT and mutant receptors (n = 3–6). *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001.

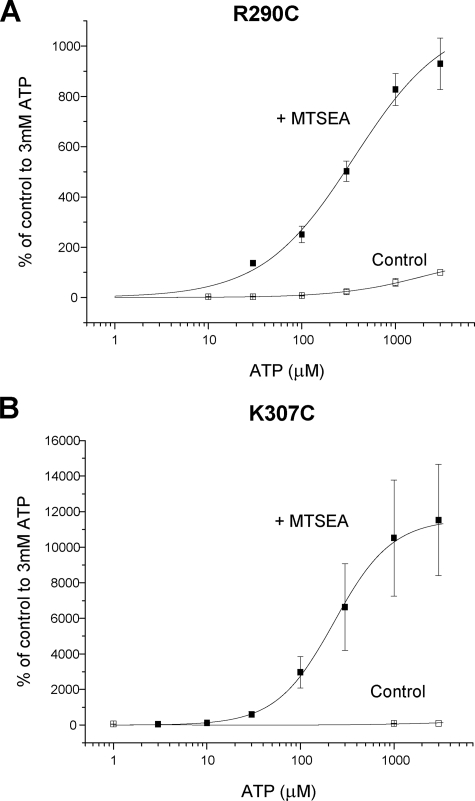

At R290C the amplitude of responses was still rising in response to increases from 3 to 10 mm ATP, indicating a large decrease in ATP sensitivity at this mutant. MTSEA application for 10 min in the absence of agonist resulted in a large increase in amplitude of responses and a leftward shift in the concentration response to ATP and now a fully saturating concentration response was generated following MTSEA treatment (pEC50 values 2.8 ± 0.1, estimated from a free fit as responses did not saturate for control, to 3.3 ± 0.2, p < 0.01, for MTSEA, n = 3–4) (Fig. 4). Responses to a high concentration of ATP (10 mm) were small (∼50 nA) for the K307C mutant and responses were below the limit of detection for 1 mm ATP, however, following a 10-min MTSEA treatment (and washout) there was a very large increase in the amplitude of responses and the pEC50 for ATP in the presence of MTSEA was 3.5 ± 0.1 (n = 7). As MTSEA was able to rescue the responses to mutants with small amplitude currents we tested whether MTSEA had any effect on mutants where receptor protein could be detected at the cell surface but little or no current was detected in response to high concentrations of ATP. At N288C the responses to ATP (3 mm) were reduced to 22 ± 5% of control following MTSEA treatment, this effect was sustained on MTSEA washout. For mutants K69C and K71C, ATP-evoked currents were still not detected following MTSEA treatment.

FIGURE 4.

Effect of MTS compounds on ATP potency at P2X2 cysteine mutants. A, ATP concentration-response curve for R290C under control conditions or following washout of MTSEA after a 10-min incubation with MTSEA (1 mm)(n = 3–4). B, ATP concentration-response curve for K307C under control conditions or following washout of MTSEA after a 10-min incubation with MTSEA (1 mm)(n = 3–6). The data are expressed as a percentage of the amplitude of the response to 3 mm ATP under control conditions.

The negatively charged MTS reagent MTSES (1 mm) had no effect on currents at WT P2X2 receptors (Table 1, Fig. 3) as described previously (15). Similarly MTSES had no effect on ATP responses at F183C mutant P2X2 receptors (Table 1, Fig. 3). MTSES, however, reduced the amplitude of response to an EC50 concentration of ATP by ∼80% for mutants T184C, N288C, R290C, and K307C, a more modest ∼20% decrease was recorded at F289C (Table 1, Fig. 3). These effects were maintained following washout of MTSES indicating that the reagent was acting irreversibly to modify the introduced cysteine residues. For non-functional mutants K69C and K71C in the presence of MTSES, 3 mm ATP still did not evoke a response.

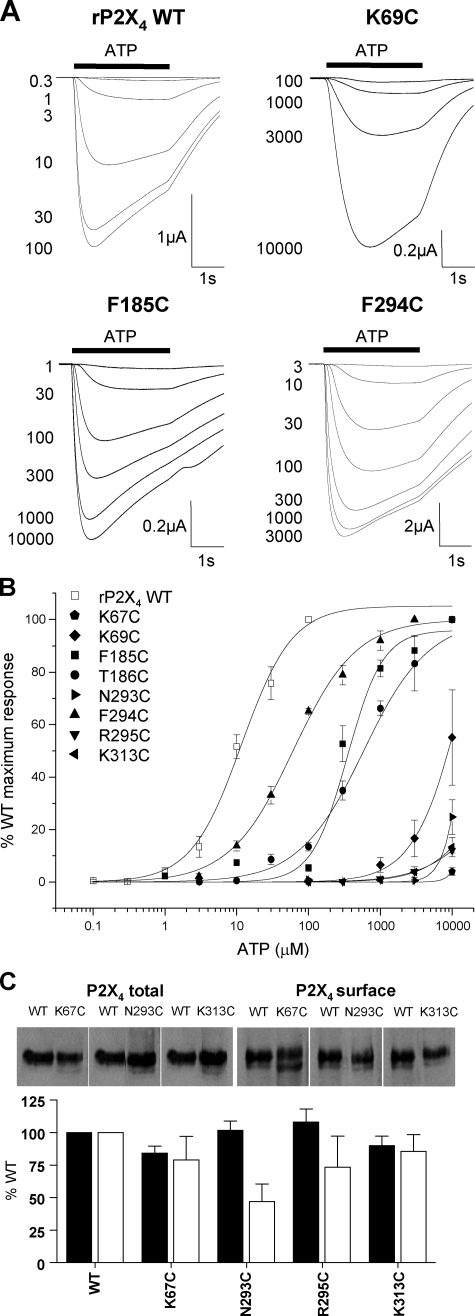

Effects of Cysteine Mutants on ATP Responses at P2X4 Receptors—The myc-tagged rat P2X4 receptor with the Y378A mutation was used as the background for these studies. The Y378A mutation was introduced to improve surface expression of the receptor (21) and increased the peak amplitude of ATP currents by >20–50-fold in the present study. ATP evoked concentration-dependent responses at the rat P2X4-myc Y378C receptor with an EC50 of ∼13 μm (Table 1, Fig. 5) similar to that reported previously for rat P2X4 receptors (29–31) and this construct will be referred to as P2X4 WT. At all cysteine mutants tested there was a decrease in ATP potency. For F185C, T186C, and F294C mutants full concentration-response curves were generated and the EC50 for ATP was increased by ∼20-, 50-, and 4-fold, respectively (Table 1, Fig. 5). For the remaining mutants (K67C, K69C, N293C, R295C, and K313C) ATP-evoked responses did not saturate at the maximum concentration tested (10 mm) and for these mutants the ATP EC50 is reported as >3 mm (Table 1, Fig. 5). Mutants K67C, R295C, and K313C had reduced maximal current amplitudes compared with WT, however, this was not reflected by a marked reduction in either total or surface expression of the receptors (Fig. 4C). For the mutant N293C the smaller peak current amplitudes may result in part from a reduction in trafficking of the receptor to the cell surface (Fig. 4C).

FIGURE 5.

Effect of point cysteine P2X4 mutations on ATP potency. ATP potency was tested on WT and P2X4 receptor mutants expressed in oocytes by two-electrode voltage clamp (holding potential = –60 mV). A, trace data representative of currents observed for wild type and mutant receptors in response to ATP applications (indicated by bar, concentration in micromolar) at 5-min intervals. B, concentration-response curves to ATP for WT and mutants K67C, K69C, F185C, T186C, N293C, F294C, R295C, and K313C. K67C, K69C, N293C, R295C, and K313C, with reduced peak currents in response to a maximal concentration of ATP, are all expressed as a percentage of peak WT maximum response whereas, all others are expressed as a percentage of their own maximum response (n = 3–4). C, Western blots of total and surface expression levels of WT and mutant P2X4 receptors with reduced peak current amplitudes. Lower panel shows densitometric analysis of the blots expressed as % of WT levels.

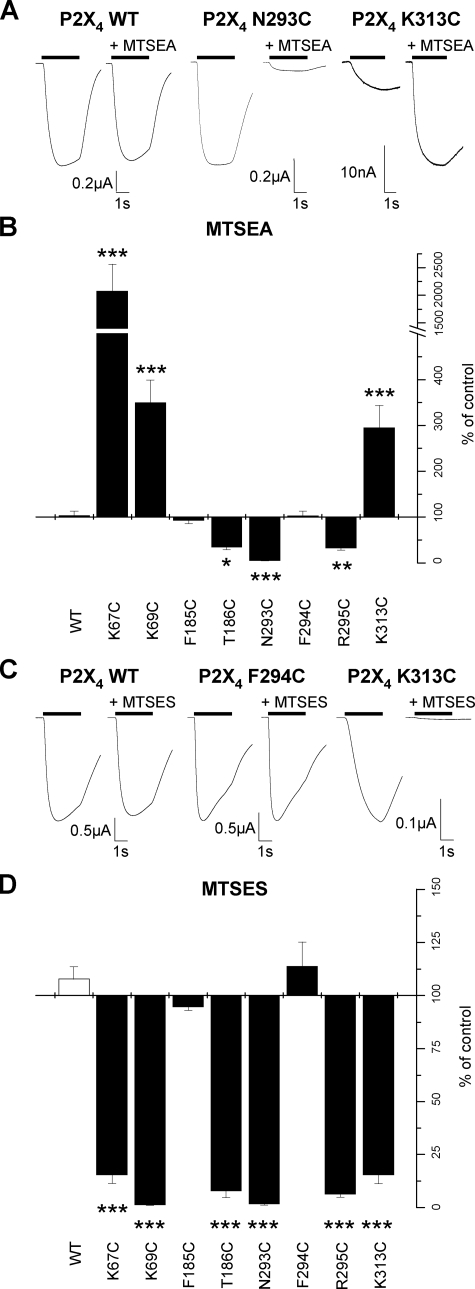

Effects of MTS Reagents on Cysteine Mutant P2X4 Receptors—Positively charged MTSEA (1 mm) had no effect on ATP-evoked currents at WT P2X4 receptors (Table 1, Fig. 6) consistent with that described previously (17). ATP-evoked responses were also unaffected by MTSEA for the mutants of the conserved aromatic phenylalanine residues F185C and F294C (Table 1, Fig. 6). At T186C and R295C, responses evoked by an EC50 concentration of ATP were reduced to ∼40% of control levels and at mutant N293C responses were reduced by ∼95% (Table 1, Fig. 6). In contrast, at mutants where a positively charged lysine residue was mutated to cysteine (Lys67, Lys69, and Lys313) application of MTSEA potentiated the amplitude of the ATP response (Table 1, Fig. 6).

FIGURE 6.

Effect of MTS compounds on ATP responses of P2X4 cysteine mutants. A, trace data representative of currents observed on the addition of MTSEA (1 mm). ATP application (EC50 concentration) is indicated by the bar. MTSEA reagent was bath applied 5 min prior to U-tube ATP coapplication with MTSEA. Traces are shown in response to ATP for a given oocyte before and during the application of MTSEA. B, graph representing the effect of MTSEA on the P2X4 WT and mutant receptors (n = 3–8). C, trace data representative of currents observed on the addition of MTSES (1 mm). ATP application (EC50 concentration) is indicated by the bar. MTSES reagent was applied in a similar manner to MTSEA. Traces are shown in response to ATP for a given oocyte before and during the application of MTSES. D, graph representing the effect of MTSES on the P2X4 WT and mutant receptors (n = 3–6). *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001.

The application of negatively charged MTSES (1 mm) had no effect on the amplitude of ATP evoked responses at WT or F185C and F294C mutant P2X4 receptors (Table 1, Fig. 6). At the remainder of the mutants (K67C, K69C, T186C, N293C, R295C, and K313C) MTSES reduced the amplitude of ATP evoked responses by ∼80–95%. These results suggest that the negative charge at this position interferes with the action of ATP possibly by repelling the negatively charged phosphate tail.

These effects of MTSEA and MTSES are broadly consistent for both the P2X2 and P2X4 receptors. However, in contrast to the P2X2 receptor the effects of MTS reagents were reversible on washout (showing 50–100% recovery following 5 min washout) indicating that either the reagent was not irreversibly modifying the receptor or that un-modified receptors were being trafficked to the cell surface during the washout period. It is known that P2X4 receptors undergo cyclical trafficking to the cell surface (21, 23, 24) so we decided to see whether longer incubation with the MTS reagents had an irreversible effect. In addition, as the MTS reagents were applied before and during ATP application the question arises as to whether the introduced cysteines are accessible in the un-liganded or ligand bound state. To address these questions we incubated mutant P2X4 receptors in membrane impermeant MTSES (1 mm) in the presence of apyrase (3.2 units/ml to break down any endogenous ATP in the solutions) for 3 h followed by washing. This treatment had no effect on the amplitude of WT P2X4 receptors compared with oocytes treated with just apyrase. For the mutants, however, there was a significant reduction in the amplitude of responses for the mutants K67C, K69C, T186C, N293C, R295C, and K313C (8 ± 1, 10 ± 3, 10 ± 3, 35 ± 8, 25 ± 6, and 17 ± 4.7% of ATP responses following apyrase treatment only and washing, with p < 0.01, 0.001, 0.005, 0.005, 0.005, 0.01, respectively, n = 4–7). These results show that longer incubations with MTS reagents are required to irreversibly modify the receptors, give equivalent results to bath-applied MTSES, and suggest that washout following short applications of MTS reagents (5–10 min) results from trafficking of un-modified mutant P2X4 receptors to the cell surface. These results also demonstrate that these introduced cysteine residues are accessible in the absence of agonist. This is consistent with previous studies on the P2X2 receptor indicating that MTS effects at the region around Lys69 and Lys71 are blocked by ATP (15) and MTSEA biotinylation studies on the P2X1 receptor showing that mutants N290C, F291C, R292C, and K309C are MTSEA biotinylated in the absence of ATP and this is reduced following application of ATP (16). Taken together these results show that the MTS reagents are acting at introduced cysteine residues that are accessible in the absence of ligand.

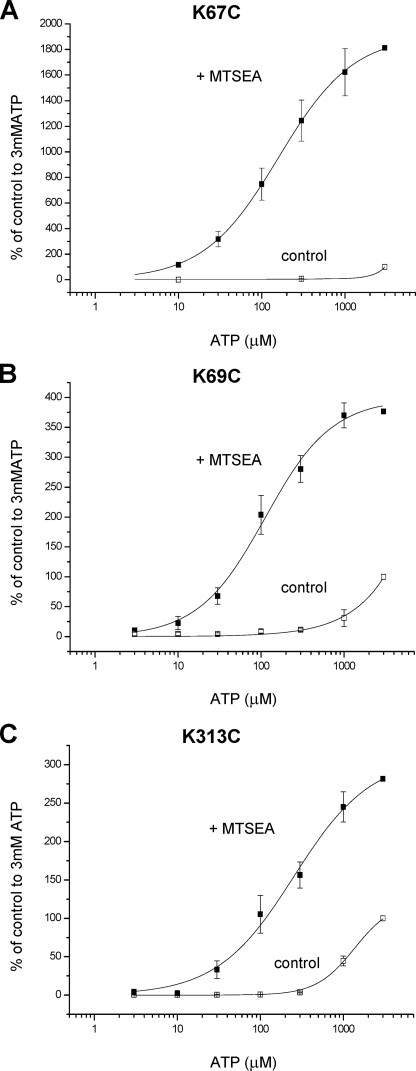

For mutants K67C, K69C, and K313, where MTSEA resulted in an increase in the amplitude of the response to ATP we constructed concentration-response curves following application of MTSEA. We found that incubation with membrane-permeant MTSEA for 1 h (in the absence of agonist) followed by washout and testing of ATP sensitivity in the absence of MTSEA resulted in an increase in ATP potency at the receptors with pEC50 values of 3.61 ± 0.24, 3.95 ± 0.09, and 3.63 ± 0.16 for K67C, K69C, and K313C, respectively (n = 4, 3, and 3) (Fig. 7). These results suggest that positive charge at these positions plays an important role in determining ATP potency.

FIGURE 7.

Effect of MTS compounds on ATP potency at P2X4 cysteine mutants. A, MTSEA significantly increased the potency of ATP and amplitude of responses at K67C mutants. B, MTSEA significantly increased the potency of ATP and amplitude of responses at K69C mutants. C, MTSEA significantly increased ATP potency and peak response at K313C mutants (n = 3–4). The data are expressed as a percentage of the amplitude of the response to 3 mm ATP. For MTSEA treatment (1 mm, 1 h incubation, followed by washout and construction of the concentration response in the absence of MTSEA) these have been corrected with a scaling factor corresponding to the mean -fold increase, at 3 mm ATP, in currents compared with untreated oocytes.

DISCUSSION

The aim of this study was to determine whether a model of the ATP binding site based on systematic mutagenesis studies on the P2X1 receptor could be applied, using cysteine-based mutagenesis, to other P2X receptor family members, and to extend this to see if the actions of ATP could be modified in a similar way by MTS reagents. The data for the effects of cysteine mutants on ATP potency at P2X2 and P2X4 receptors support previous work about residues involved in ATP action.

There are three conserved lysine residues in the extracellular domain that have been suggested to be involved in ATP binding at P2X receptors. Mutagenesis of these residues has shown a marked decrease in agonist potency at a variety of receptors with the majority of the mutations resulting in a shift in EC50 to >3 mm and in some cases, e.g. P2X2 receptors, currents are below the limit of detection even at high agonist concentrations (15). At P2X4 receptors ATP sensitivity at K67C, K69C, and K313C was increased on treatment with MTSEA, consistent with the fact that the incorporation of MTSEA at cysteine produces a side chain of similar size and charge to lysine (17). In contrast, responses were reduced by 80–95% following treatment with negatively charged MTSES. This clearly indicates that the localized charge at these three positions plays an important role in regulating ATP action at the receptor. For P2X2 receptors a response to ATP was not evoked even following MTS treatment at mutants K69C and K71C. One feature that is common to the P2X1,2,4 receptors is that the decrease in ATP potency at the cysteine mutant of the residue equivalent to Lys309 in the P2X1 receptor can be rescued by treatment with MTSEA, consistent with an important role of positive charge at this position. A recent study on the P2X2 receptor using single channel analysis has suggested the lysine residue 308 can play a role in regulation of gating of the channel. This was based on the fact that mutation of this residue could abolish spontaneous gating of the T339S mutant P2X2 channel and that mutation K308R reduced ATP potency by ∼200-fold and decreased the amplitude of the maximal response compared with control (32). In the current study the concentration responses to P2X2 K307C and P2X4 K313C did not saturate so it is not possible to determine whether there was a reduction in the amplitude of the maximal response. At the P2X1 receptor the ∼200-fold reduction in ATP potency at K309R and K309C mutants did not result in a decrease in the amplitude of the maximal response (16, 22) as would have been expected if an effect on gating of the receptor has been primarily responsible for the reduction in potency (33). These results suggest that the effects of mutation of this conserved residue can be manifest as a principal effect on ATP binding at the P2X1 receptor (16) and an additional effect on gating at the P2X2 receptor (32). This may indicate that in the P2X2 receptor the lysine residue interacts with another amino acid that is not conserved at the P2X1 receptor to regulate gating. Taken together these results support that the three positively charged lysine residues play an important role in ATP action most likely contributing to the ATP binding site. Indeed it would be unusual to have an ATP-binding protein without positive charge being important in coordinating agonist binding.

The mutations of conserved aromatics F183C in P2X2 and F185C in the P2X4 receptor gave rise to a modest 3- and 20-fold decrease in ATP potency at the receptors. This is consistent with previous studies on P2X1 and P2X4 receptors (34, 35) and indicates that this conserved residue contributes to ATP action. The MTS reagents used are of similar size (or smaller) than ATP and can gain access to the ATP binding pocket. The effects of the MTS compounds at cysteine mutants of the adjacent threonine residue (T184C and T186C for P2X2 and P2X4, respectively) suggest that this region of the receptor is accessible to these reagents and the lack of effect at the cysteine-substituted phenylalanine residues is likely to reflect that this residue is either not very close to the ATP binding pocket or is involved in interaction with other residues that could regulate gating. The former interpretation suggests that the phenylalanine may not play a direct role in binding of the adenine ring of ATP as we have suggested previously for the P2X1 receptor (34). However, cysteine substitution does give rise to changes in agonist action at the receptor. The introduction of a polar side chain (cysteine) to replace the non-polar phenylalanine could have an effect on bonding/electrostatic interactions or a structural change to the receptor.

Mutation of threonine in the conserved FT motif to cysteine resulted in a 10- and 40-fold decrease in ATP potency at P2X2 and P2X4 receptors. Previous studies on the P2X2 receptor have shown that alanine substitution at this residue deceases ATP potency by ∼100-fold (15). This is the first time a mutation has been made at this position for the P2X4 receptors and it supports a similar mode of agonist action as P2X1 and P2X2 receptors. At P2X2 and P2X4 receptors the response was inhibited by MTSES. These results clearly indicate that modification of the side chain at this conserved threonine residue can regulate channel function. Close to the FT motif is a nearby conserved lysine residue that has been shown to be involved in regulating ATP potency (Lys190 in P2X1 and Lys188 in P2X2 that when mutated to alanine resulted in ∼10- (22) and ∼100-fold decreases in ATP potency (36)). Thus this region in the middle of the extracellular loop of the channel plays a role in regulation of ATP potency, however, whether this results from an effect on agonist binding and/or gating remains to be determined. What is clear is that residues involved in agonist action at P2X receptors are not just focused around regions close to the transmembrane segments and the pore of the channel.

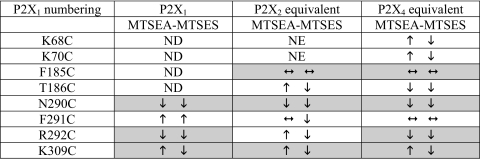

At the conserved NFR motif cysteine substitution at Asn and Arg reduced ATP potency by >300-fold and gave marked reductions in peak current amplitudes (>80%) at P2X2 and P2X4 receptors. The asparagine to cysteine mutation had the same effect at P2X2 (N288C) and P2X4 (N293C) receptors with inhibition of currents by either MTS reagent as reported previously for P2X1 receptors (16). The reduction of ATP responses at the mutants of the conserved arginine by MTSES is the same for P2X1,2,4 receptors, however, MTSEA inhibited P2X1 and P2X4 receptors, but potentiated the P2X2 receptor (Ref. 16 and this study, Table 2). This shows that the P2X1 and P2X4 receptors are similar in that the MTS reagents interfere with the action of ATP in a way that is charge independent. However, for P2X2 the results are consistent with the polarity of charge at this position being important. When the phenylalanine of the NFR motif was replaced with cysteine there was only a modest ∼4-fold reduction in ATP potency, no effect on peak current amplitude, and MTS reagents were ineffective. This suggests that at P2X2 and P2X4 receptors the conservation of the asparagine and arginine residues is more important in regulating the actions of ATP than the phenylalanine of which they are adjacent. At P2X1 receptors and a non-desensitizing chimeric P2X1/2 receptor, marked effects of >100-fold decrease in ATP potency with no effect on the peak response were recorded with the equivalent mutations (16, 18). Taken together these results show that whereas there are marked similarities between the receptors, there are also differences in regulation of ATP potency between the P2X receptor subunits (e.g. the effects of MTSEA on cysteine substitution of the arginine of the NFR motif). This is consistent with variations in the pharmacological properties of P2X receptors and suggests that non-conserved amino acids are associated with agonist action.

TABLE 2.

Summary of data for the effects of MTS reagents at P2X receptor cysteine mutants

Arrows correspond to significant effects of MTS reagents on ATP responses. Shaded areas correspond to similar effects of the MTS reagents at different P2X receptor subtype mutants. Data for the P2X1 receptor from (16). ND, not done; NE, no effect could be determined.

The present study shows that the NFR region plays an important role in regulation of ATP action at P2X2 and P2X4 receptors. We have previously shown, for P2X1 receptors, that reductions in ATP potency at cysteine mutants of the NFR motif are likely to result from effects on agonist binding at Arg292 and effects on both binding and gating for Asn290 and Phe291 (16). The contribution of this region to the agonist binding site is supported by a recent paper (18) showing that the phenylalanine is close to the conserved Lys68 residue in the P2X1 receptor and cysteine mutants K68C and F291C can form an inter-subunit disulfide bond and this is inhibited by ATP, suggesting that both residues are close to the ATP binding site. Similarly a recent single channel study on P2X2 receptors reported that the reduction of ATP potency for the K69A mutant of the P2X2 receptor results predominantly from an effect on agonist binding (32). So how may the NFR region be involved in coordination of ATP binding? Previously we had suggested that the phenylalanine residues in the NFR motif were involved in binding of the adenine ring of ATP. However, the present results from P2X2 and P2X4 receptors with modest changes in ATP for cysteine mutants of these phenylalanines and the lack of effect of MTS reagents on ATP responses suggests that the conserved aromatic residue may not contribute directly to agonist recognition. The inhibition of cysteine-substituted mutants of the arginine of the NFR motif for P2X1 and P2X4 receptors by both positive and negatively charged MTS reagents suggests that arginine is not directly involved in binding of the phosphate tail of ATP. This suggests that asparagine and arginine are most likely involved in binding of the ribose and/or adenine ring of ATP.

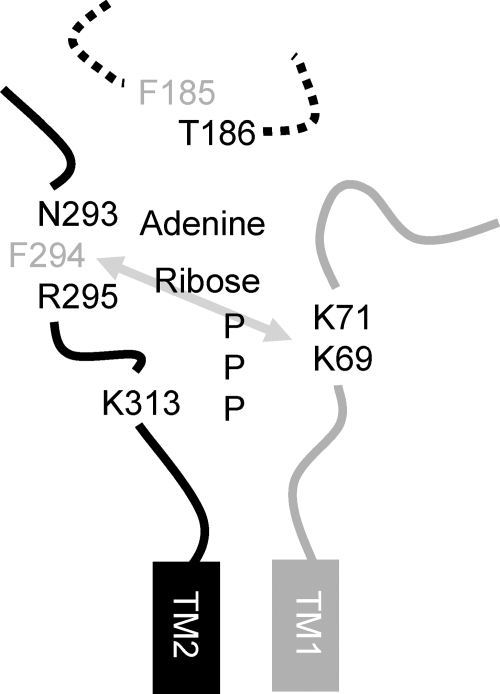

In summary our results support the idea that mammalian P2X receptors share a common agonist binding site with the negative charge of ATP coordinated by positively charged lysine residues and the NFR motif involved in binding of the adenine/ribose component (Fig. 8). The conserved FT motif also contributes to agonist action, however, whether this results from an effect on agonist binding and/or gating remains to be determined.

FIGURE 8.

Model of the ATP binding site at P2X receptors. Portions of the extracellular loop adjacent to either the first (in gray) or second (in black) transmembrane domain are shown for two adjacent P2X receptor subunits (numbering for the P2X4 receptor). The gray arrow represents the disulfide bond that can be formed between cysteine mutations of these residues at the P2X1 receptor (18). Residues that showed a decrease in ATP potency when mutated to cysteine are shown, those in black correspond to those that were modified by MTS reagents, whereas those in gray were unaffected by either MTSEA or MTSES. Positively charged MTSEA increased the amplitude and potency of responses at cysteine mutants of the P2X4 receptor at positions Lys69, Lys71 and Lys313, this suggests a role of these residues in coordinating the binding of the negatively charged phosphate of ATP, however, it is possible that they also contribute to the gating of the channel as has been suggested for the residue equivalent to Lys313 at the P2X2 receptor (32). The conserved FT region is shown as a dotted line as it has been shown to be involved in agonist potency and is unclear whether the effects result from changes in agonist binding and/or gating. One possibility is that threonine could face the agonist binding pocket.

Author's Choice—Final version full access.

This work was supported by the Wellcome Trust. The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: MTS, methanethiosulfonate; MTSEA, (2-aminoethyl)methanethiosulfonate hydrobromide; MTSES, sodium (2-sulfonatoethyl)methanethiosulfonate; WT, wild type.

R. A. McMahon, T. M. Egan, P. T. Hurley, A. Nelson, M. Rogers, and F. Martin, submitted to EMBL-EBI Data Bank with accession number AF109387.

References

- 1.North, R. A. (2002) Physiol. Rev. 82 1013–1067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hechler, B., Lenain, N., Marchese, P., Vial, C., Heim, V., Freund, M., Cazenave, J.-P., Cattaneo, M., Ruggeri, Z. M., Evans, R. J., and Gachet, C. (2003) J. Exp. Med. 198 661–667 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Souslova, V., Cesare, P., Ding, Y., Akopian, A. N., Stanfa, L., Suzuki, R., Carpenter, K., Dickenson, A., Boyce, S., Hill, R., Nebenius-Oosthuizen, D., Smith, A. J., Kidd, E. J., and Wood, J. N. (2000) Nature 407 1015–1017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tsuda, M., Shigemoto-Mogami, Y., Koizumi, S., Mizokoshi, A., Kohsaka, S., Salter, M. W., and Inoue, K. (2003) Nature 424 778–783 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chessell, I. P., Hatcher, J. P., Bountra, C., Michel, A. D., Hughes, J. P., Green, P., Egerton, J., Murfin, M., Richardson, J., Peck, W. L., Grahames, C. B., Casula, M. A., Yiangou, Y., Birch, R., Anand, P., and Buell, G. N. (2005) Pain 114 386–396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cockayne, D. A., Hamilton, S. G., Zhu, Q.-M., Dunn, P. M., Zhong, Y., Novakovic, S., Malmberg, A. B., Cain, G., Berson, A., Kassotakis, L., Hedley, L., Lachnit, W. G., Burnstock, G., McMahon, S. B., and Ford, A. P. (2000) Nature 407 1011–1015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Finger, T. E., Danilova, V., Barrows, J., Bartel, D. L., Vigers, A. J., Stone, L., Hellekant, G., and Kinnamon, S. C. (2005) Science 310 1495–1499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ke, H. Z., Qi, H., Weidema, A. F., Zhang, Q., Panupinthu, N., Crawford, D. T., Grasser, W. A., Paralkar, V. M., Li, M., Audoly, L. P., Gabel, C. A., Jee, W. S., Dixon, S. J., Sims, S. M., and Thompson, D. D. (2003) Mol. Endocrinol. 17 1356–1367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burnstock, G. (2006) Pharmacol. Rev. 58 58–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Walker, J. E., Saraste, M., Runswick, M. J., and Gay, N. J. (1982) EMBO J. 1 945–951 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vial, C., Roberts, J. A., and Evans, R. J. (2004) Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 25 487–493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roberts, J. A., Vial, C., Digby, H. R., Agboh, K. C., Wen, H., Atterbury-Thomas, A. E., and Evans, R. J. (2006) Pflugers Arch. 452 486–500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rassendren, F., Buell, G., Newbolt, A., North, R. A., and Surprenant, A. (1997) EMBO J. 16 3446–3454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Egan, T. M., Haines, W. R., and Voigt, M. M. (1998) J. Neurosci. 18 2350–2359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jiang, L.-H., Rassendren, F., Surprenant, A., and North, R. A. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275 34190–34196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roberts, J. A., and Evans, R. J. (2007) J. Neurosci. 27 4072–4082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fountain, S. J., and North, R. A. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281 15044–15049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marquez-Klaka, B., Rettinger, J., Bhargava, Y., Eisele, T., and Nicke, A. (2007) J. Neurosci. 27 1456–1466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stojilkovic, S. S., Tomic, M., He, M. L., Yan, Z., Koshimizu, T. A., and Zemkova, H. (2005) Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1048 116–130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yan, Z., Liang, Z., Tomic, M., Obsil, T., and Stojilkovic, S. S. (2005) Mol. Pharmacol. 67 1078–1088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Royle, S. J., Bobanovic, L. K., and Murrell-Lagnado, R. D. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277 35378–35385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ennion, S., Hagan, S., and Evans, R. J. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275 29361–29367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bobanovic, L. K., Royle, S. J., and Murrell-Lagnado, R. D. (2002) J. Neurosci. 22 4814–4824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Royle, S. J., Qureshi, O. S., Bobanovic, L. K., Evans, P. R., Owen, D. J., and Murrell-Lagnado, R. D. (2005) J. Cell Sci. 118 3073–3080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ennion, S. J., and Evans, R. J. (2002) Mol. Pharmacol. 61 303–311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Evans, R. J., Lewis, C., Buell, G., Valera, S., North, R. A., and Surprenant, A. (1995) Mol. Pharmacol. 48 178–183 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Clyne, J. D., Wang, L. F., and Hume, R. I. (2002) J. Neurosci. 22 3873–3880 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Akabas, M. H., Stauffer, D. A., Xu, M., and Karlin, A. (1992) Science 258 307–310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bo, X., Zhang, Y., Nassar, M., Burnstock, G., and Schoepfer, R. (1995) FEBS Lett. 375 129–133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Buell, G., Lewis, C., Collo, G., North, R. A., and Surprenant, A. (1996) EMBO J. 15 55–62 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Silberberg, S. D., Chang, T. H., and Swartz, K. J. (2005) J. Gen. Physiol. 125 347–359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cao, L., Young, M. T., Broomhead, H. E., Fountain, S. J., and North, R. A. (2007) J. Neurosci. 27 12916–12923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Colquhoun, D. (1998) Br. J. Pharmacol. 125 924–947 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Roberts, J. A., and Evans, R. J. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279 9043–9055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zemkova, H., Yan, Z., Liang, Z., Jelinkova, I., Tomic, M., and Stojilkovic, S. S. (2007) J. Neurochem. 102 1139–1150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jiang, L.-H., Rassendren, F., Spelta, V., Surprenant, A., and North, R. A. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276 14902–14908 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fountain, S. J., Parkinson, K., Young, M. T., Cao, L., Thompson, C. R., and North, R. A. (2007) Nature 448 200–203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]