Abstract

A proteomic survey of the halophilic archaeon Haloferax volcanii was performed by comparative two-dimensional gel electrophoresis in order to determine the molecular effects of salt stress on the organism. Cells were grown under optimal (2.1 M) and high (3.5 M) NaCl conditions. From this analysis, over 44 protein spots responsive to these conditions were detected. These spots were excised, digested in-gel with trypsin, subjected to QSTAR tandem mass spectrometry (LC/MS/MS) analysis, and identified by comparing the MS/MS-derived peptide sequence to that deduced from the H. volcanii genome. Approximately 40 % of the proteins detected (18 in total) displayed differential abundance based on the detection of at least two peptide fragments per protein and overall MOWSE scores of ⩾ 75 per protein. All of these identified proteins were either uniquely present or 2.3- to 26-fold higher in abundance under one condition compared to the other. The majority of proteins identified in this study were preferentially displayed under optimal salinity and primarily involved in translation, transport and metabolism. However, one protein of interest whose transcript levels were confirmed in these studies to be upregulated under high salt conditions was identified as a homologue of the phage shock protein PspA. The pspA gene belongs to the psp stress-responsive regulon commonly found among Gram-negative bacteria where its transcription is stimulated by a wide variety of stressors, including heat shock, osmotic shock and prolonged stationary-phase incubation. Homologues of PspA are also found among the genomes of cyanobacteria, higher plants and other Archaea, suggesting that this protein may retain some aspects of functional conservation across the three domains of life. Given its integral role in sensing a variety of membrane stressors in bacteria, these results suggest that PspA may play an important role in hypersaline adaptation in H. volcanii.

INTRODUCTION

Halophilic microbes have evolved a host of unique strategies to combat the desiccating effects of salinity (reviewed by Dennis & Shimmin, 1997; Grant et al., 1998; Madern et al., 2000; Oren, 1998, 1999). The haloarchaea are particularly adept at co-existing with molar levels of salt, and thus are the major colonizers of hypersaline habitats (Javor, 1989). Haloferax volcanii is a model haloarchaeon that grows optimally in environments containing 2–2.5 M NaCl, but is capable of growth in salinities ranging from 1.5 to 4 M NaCl (Mullakhanbhai & Larsen, 1975). Both salinity-mediated gene regulation, and protein expression and activity have been examined in H. volcanii (Bidle, 2003; Bidle et al., 2007; Daniels et al., 1984; Ferrer et al., 1996; Mojica et al., 1997), although many of the precise genetic mechanisms involved in these adaptations await further investigation.

To comprehensively identify additional genes directly responsible for the maintenance and survival of H. volcanii upon exposure to non-optimal salinity, a proteomic approach was employed with the aim of identifying proteins that contribute to the adaptation of this organism when grown in two dramatically different salinities. One specific protein identified in these studies, the bacterial-like stress response protein PspA, was of particular interest as its transcripts were also found to be regulated in response to non-optimal high salinity.

In prokaryotes, cell-membrane stressors (e.g. hyper- or hypo-osmotic shock, pressure, lipid biosynthesis defects) impart inducing signals that must be received by effector molecules and subsequently propagated into changes in gene expression in order for the cell to survive. In Gram-negative bacteria, several of these effector molecules have been well-studied and include the alternative sigma factor σE (RpoE) and the phage shock protein PspA (reviewed by Rowley et al., 2006). PspA was discovered during studies examining the response of Escherichia coli to filamentous phage infection (Brissette et al., 1990, 1991). Transcription of the psp regulon, consisting of the polycistronic operon pspABCE and the monocistronic gene pspG, is initiated by the alternate sigma factor σ54, and is controlled by both positive and negative feedback inhibition (Weiner et al., 1991). Under normal growth conditions within a cell, PspA acts as a negative regulator of the psp regulon by directly interacting with the transcriptional regulator PspF and suppressing its primary activity of recruiting σ54 to initiate transcription of pspABCDE and pspG (Jovanovic et al., 1996). Upon sensing cellular stress, the cytoplasmic membrane proteins PspB and PspC bind PspA, releasing it from PspF. This event activates transcription of the psp regulon and leads to abundant pspA expression.

In addition to phage infection, induction of the psp regulon is stimulated by a wide variety of stressors in Escherichia coli, including heat and osmotic shock, inhibition of Tat-dependent protein secretion or lipid biosynthesis, and prolonged stationary-phase incubation (Bergler et al., 1994; Brissette et al., 1990; Kleerebezem & Tommassen, 1993; Kleerebezem et al., 1996; Weiner & Model, 1994). What unites these various types of stresses is the disruption of the proton motive force (PMF) in the cell. Thus, it is widely hypothesized that the major function of the psp regulon is to stabilize and maintain PMF within a stressed cell (Darwin, 2005; Rowley et al., 2006). PspA is hypothesized to tightly associate with the cytoplasmic membrane during cellular stress and while experimental evidence for this hypothesis has yet to be shown, structural analysis of E. coli PspA revealed that it forms a symmetrical oligomeric ring that could interact with the F1 subunit of the F0F1-ATPase in the membrane, lending stability (Hankamer et al., 2004).

The psp regulon is found among a wide variety of both Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria, including Yersinia enterocolitica, Salmonella typhimurium and Bacillus cereus, and its role in the extracytoplasmic stress response in these organisms has been well-established (reviewed by Darwin, 2005). Homologues of PspA (designated VIPP1) are also found among cyanobacteria and higher plants and are essential for photosynthesis as they are required for thylakoid biogenesis (Westphal et al., 2001). Interestingly, heterologous expression of VIPP1 has been shown to complement E. coli pspA mutants in restoring Tat-dependent protein export defects, remarkably demonstrating that these proteins may retain some aspects of functional conservation across the bacterial and eukaryotic domains (DeLisa et al., 2004).

To date, aside from genomic annotations, there has been no description of a functional PspA-like protein in Archaea, nor any study detailing its expression. In this study, we clearly demonstrate the presence and salinity-mediated differential protein and transcript levels of an H. volcanii PspA homologue that is 27 % identical and 53 % similar to E. coli PspA. Interestingly, the majority of psp regulon components of E. coli which interact with and are regulated by PspA are not conserved in Archaea, thus suggesting a different type of PspA-mediated control exists in this unusual domain of life.

METHODS

Strain and growth media

Haloferax volcanii strain DS70 (Wendoloski et al., 2001) was grown with shaking (180 r.p.m.) at 45 °C (Robinson et al., 2005) and cultured in a medium containing (l−1) 125 g (2.1 M or 12 %, optimal salinity) or 206 g (3.5 M or 20 %, high, non-optimal salinity) NaCl, 45 g MgCl2 . 6H2O, 10 g MgSO4 . 7H2O, 10 g KCl, 1.34 ml 10 % CaCl2 . 2H2O, 3 g yeast extract and 5 g tryptone (Robb et al., 1995).

Preparation and separation of proteins by two-dimensional gel electrophoresis (2-DE)

Cells were harvested from mid-exponential phase at an OD600 between 0.8 and 1.0 by centrifugation (6000 g, 5 min at 4 °C), and cell pellets were resuspended in 1 ml TRIzol (phenol/guanidine isothiocyanate; Invitrogen) per 100 mg cells (wet wt). Protein sample was extracted and 125 μg was separated by 2-DE using 11 cm IPG strips with a pI range of 3.9–5.1 and Criterion pre-cast gels, as described previously (Kirkland et al., 2006). Precision Plus protein molecular mass standards (Bio-Rad) were used for the SDS-PAGE dimension. Protein concentration was determined by the Bradford Protein Assay using BSA as a standard, according to the supplier’s instructions (Bio-Rad). Proteins were stained in gel overnight in 150 ml SYPRO Ruby fluorescent protein stain and destained according to the supplier’s instructions (Bio-Rad). Biological duplicate gels were imaged with the Bio-Rad Molecular Imager FX Scanner with a 532 nm excitation laser and a 555 nm LP emissions filter. Acquired images were analysed with PDQuest software v. 7.0.1 (Bio-Rad). Protein spots of interest were excised for analysis by MS using the Bio-Rad ProteomeWorks spot cutter with fluorescent enclosure.

In-gel tryptic digestion and tandem mass spectrometric (MS/MS) analysis of proteins

2-DE excised gel spots were reduced, alkylated and digested with trypsin (Promega) in-gel using an automated platform for protein digestion (ProGest; Genomics Solutions). Protein digests were separated by capillary reversed-phase HPLC (PepMap C18 column; 15 cm × 75 μm i.d.) with a linear gradient of 5–40 % (v/v) acetonitrile for 25 min at 200 nL min−1 as previously described (Kirkland et al., 2007). MS/MS analysis was performed online using a hybrid quadrupole time-of-flight instrument (QSTAR XL hybrid LC/MS/MS) equipped with a nanoelectrospray source (Applied Biosystems) and operated with Analyst QS v1.1 data acquisition software as described by Kirkland et al. (2007). MS data were searched against the deduced proteome of H. volcanii DS2 (4074 total ORFs; April 2007 annotation; http://archaea.ucsc.edu/) and GenBank, EMBL and SWISS-PROT databases at the National Center for Biotechnology Information (Bethesda) using the Mascot v2.1 search algorithm (Matrix Science). Carbamidomethylation of cysteines was allowed as a fixed modification, and variable modifications of methionine oxidation, pyro-Glu from glutamine or glutamic acid, acetylation, and phosphorylation of serine, threonine and tyrosine residues were also included in the search parameters. Precursor and fragment ion mass tolerances were set to 0.3 Da. Probability-based MOWSE scores above the calculated threshold value (P<0.05) were considered for protein identification. The pI and molecular mass values for deduced proteins were calculated as described by Gasteiger et al. (2001).

RNA isolation and quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR)

Transcript levels specific to the pspA gene were analysed using qRT-PCR for triplicate samples collected from replicate cultures of H. volcanii cultured in either optimal (12 % NaCl) or non-optimal high salt (20 % NaCl) medium. RNA samples were harvested from mid-exponential cultures using Tri Reagent (MRC). Following extraction, RNA was treated with 1 μl TURBO DNase (Ambion) for 30 min at 37 °C, followed by phenol/chloroform extraction and DNA precipitation. DNase-free RNA was quantified using an Eppendorf BioPhotometer. First strand cDNA was synthesized from 1 μg total RNA using the Stratagene Brilliant SYBR Green qRT-PCR, AffinityScript Two-Step Master Mix kit, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Priming was initiated by using random hexamers provided with the kit. Negative controls consisted of eliminating the AffinityScript reverse transcriptase from the first strand cDNA reaction and using this RNA as template in parallel experiments to ensure no DNA contamination in the RNA samples.

qRT-PCR was initiated by adding 2 μl of the first-strand cDNA synthesis reaction to pspA-specific forward (5′-CGAAGAGAACGTCGAAAAGC-3′) and reverse (5′-CTTCAGCTCTTCGAGTTCGG-3′) primers. The reactions were run in a RotorGene RG-3000 (Corbett Research) for 45 cycles of 95 °C for 30 s; 50 °C for 1 min; and 72 °C for 1 min. qRT-PCR progression was monitored using the intercalating dye SYBR Green. Expression of the pspA gene was normalized to 16S expression and relative quantification was performed using protocols in the RotorGene software package (Corbett Research).

A standard curve was performed to monitor amplification efficiency using the following strategy. Both pspA and 16S gene fragments were amplified from genomic DNA, cloned into the pCR2.1-TOPO cloning vector (Invitrogen) and transformed into TOP 10 competent E. coli cells (Invitrogen). Plasmid DNA was purified from positive clones using the QIAprep Spin Miniprep kit (Qiagen) and linearized by restriction enzyme digestion. Standard curves having an r2 value of ~0.98 were generated using serially diluted linear plasmid DNA for each gene. Primer sets used showed an amplification efficiency [efficiency = 10(−1/slope)] above 80 %.

Northern analysis

Total RNA (~8 μg) obtained from a non-optimal, high-salt culture was denatured by resuspension in formaldehyde loading dye (Ambion) and heating at 65 °C prior to loading onto a 12 % formaldehyde gel. Following electrophoresis, RNA was transferred onto a Hybond-N+ nylon membrane (Amersham) and cross-linked using a UV Stratalinker (UVC 500; Hoefer). A probe was created from a 500 bp internal pspA fragment by random priming using the Sequenase Random Primer Labelling kit (USB) and 50 μCi [α-32P]dATP (MP Biomedicals). Hybridization was performed overnight in 5 ml QuikHyb solution (Stratagene) in a rotating hybridization oven set to 60 °C. The membrane was washed twice in 2 × SSC/0.1 % SDS at room temperature for 15 min and once in 0.1 × SSC/0.1 % SDS at 60 °C for 30 min. The washed membrane was exposed to Kodak Biomax XAR film with an intensifying screen at −80 °C for 24 h before development.

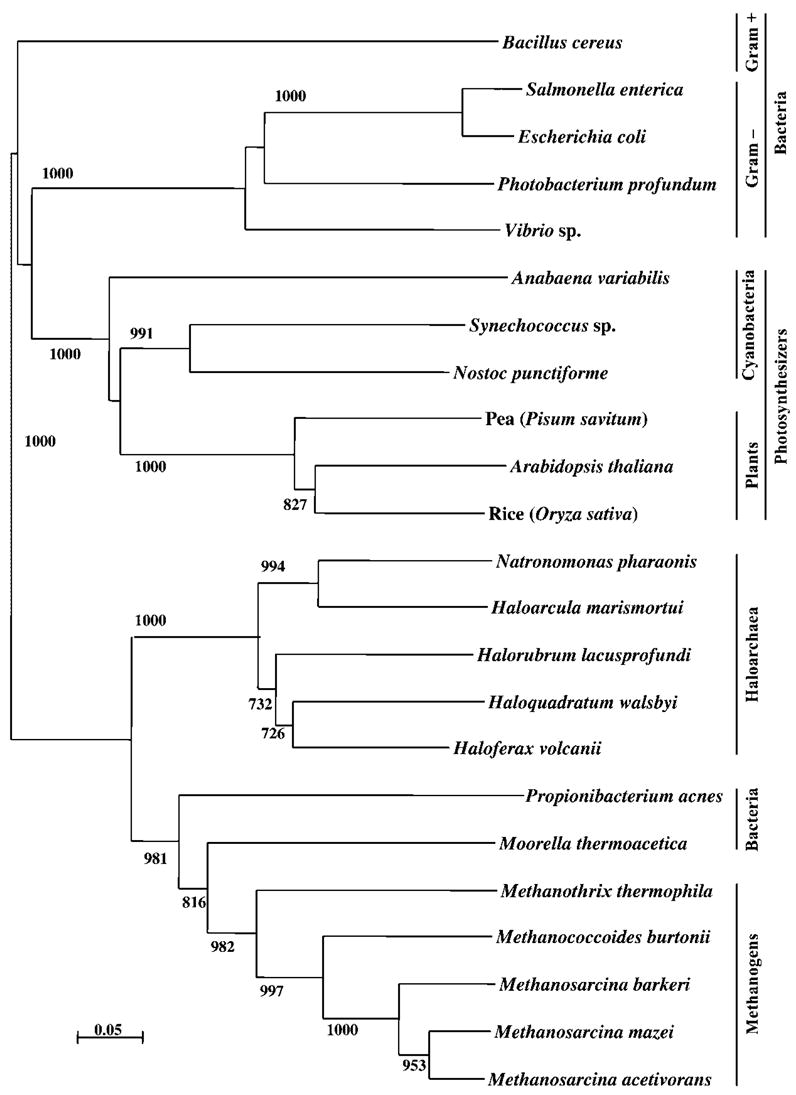

Phylogenetic analyses

Sequences used to construct a phylogenetic tree of PspA homologues were obtained by performing a protein BLAST search within GenBank on the NCBI website. The sequence alignments were performed using CLUSTAL_X (Thompson et al., 1997), and the tree was constructed using NJPlot (Perrière & Gouy, 1996). Amino acid sequences used in the tree can be found with the following accession numbers: Haloquadratum walsbyi (YP_658728), Haloarcula marismortui (YP_137510), Halorubrum lacusprofundi (ZP_02016644), Methanococcoides burtonii (YP_565929), Methanosarcina acetivorans (NP_616394), Methanosarcina barkeri (YP_306682), Methanosarcina mazei (NP_634548), Methanothrix (‘Methanosaeta’) thermophila (YP_843278), Moorella thermoacetica (YP_429577), Natronomonas pharaonis (YP_326857), Pisum savitum (Q03943), Oryza sativa (NP_001045073), Arabidopsis thaliana (NP_564846), Propionibacterium acnes (YP_055413), Bacillus cereus (ABS23681), Nostoc punctiforme (ZP_00108081), Photobacterium profundum SS9 (YP_130624), Synechococcus sp. (NP_442275), Anabaena variabilis (YP_320683), Vibrio sp. (EDN56445), Escherichia coli (ABJ00758) and Salmonella enterica (CAD01639).

RESULTS

Proteomic analyses

H. volcanii cells were grown in either optimal (12 % NaCl) or non-optimal high salt (20 % NaCl) medium in biological duplicate experiments and analysed for differentially expressed proteins via comparative 2-DE. Protein spots of differential abundance in the 2-DE gels were excised and identified by QSTAR XL hybrid LC/MS/MS. From these analyses over 44 protein spots were either unique or of greater than twofold higher abundance under one saline condition compared to the other. Eighteen of these differential spots were mapped to proteins with high confidence based on MS detection of at least two peptide fragments with MOWSE scores ⩾75 for each protein.

Protein isoforms identified as either dominantly or uniquely present in either optimal or non-optimal, high-salt growth medium are indicated in Table 1. All of the identified proteins migrated at an observed pI similar to that calculated for the deduced protein sequence, and the majority of these proteins also migrated at a molecular mass similar to that calculated from the deduced protein sequence. Although one-third of the proteins had observed molecular masses 5 kDa greater than calculated in silico, this finding is common for proteins of the haloarchaea (Izotova et al., 1983) and is probably due to the predominance of acidic residues in these salt-loving proteins compared to the mesophilic proteins used as molecular mass standards for the SDS-PAGE dimension of the 2-DE gel.

Table 1.

Selected differentially regulated proteins identified by 2-DE and MS/MS

The H. volcanii genome database (April 2007 TIGR annotation; http://archaea.ucsc.edu/) was searched using the partial amino acid sequences obtained for the putative identity of each protein examined. MOWSE scores less than 75, number of peptide fragments detected (peptide no.) less than two, and –fold increases less than two were not considered

| Description | HVO GenBank no.* | MOWSE score | Peptide no. | Sample (M NaCl) | Fold increase† | pI

|

Molecular mass (kDa)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Expected | Observed | Expected | Observed | ||||||

| Typtophanase (tnaA) | HVO_0009 | 224–316 | 7 | 2.1 | 19–26 | 5.01 | 5.0 | 52 | 51 |

| ABC transporter, dipeptide binding protein | HVO_0062 | 191 | 4 | 2.1 | 9.4 | 4.02 | 4.25 | 67.3 | 65 |

| Ribosomal protein S7 (rpsG) | HVO_0354 | 316 | 6 | 2.1 | U | 6.86 | >5.1 | 19.2 | 24 |

| FeS assembly ATPase (sufC) | HVO_0859 | 439 | 8 | 2.1 | U | 4.24 | 4.4 | 33.5 | 41 |

| Protein of unknown function, DUF127 | HVO_1173 | 75 | 2 | 2.1 | U | 4.51 | 4.8 | 17.5 | 17 |

| Dihydroxyacetone kinase (dhaL) | HVO_1545 | 310 | 7 | 2.1 | U | 4.38 | 4.5 | 24.8 | 32 |

| Ribosomal protein S24e | HVO_1896 | 122 | 3 | 2.1 | 19.9 | 4.91 | 4.9 | 10.2 | 10 |

| Ribosomal protein L24 (rplX) | HVO_2553 | 102 | 2 | 2.1 | 15 | 4.66 | 4.7 | 13.4 | 12 |

| GMP synthase, C-terminal domain (guaA) | HVO_2625 | 132 | 3 | 2.1 | U | 4.66 | 4.7 | 33.9 | 47 |

| Protein of unknown function, DUF655 | HVO_2747 | 98 | 3 | 2.1 | U | 4.59 | 4.6 | 22.3 | 27 |

| Ribosomal protein S4 (rpsD) | HVO_2783 | 133 | 2 | 2.1 | U | 5.17 | 5.1 | 20.1 | 17 |

| Ribosomal protein S13p/S18e (rpsM) | HVO_2784 | 167 | 3 | 2.1 | U | 5.09 | 5.1 | 18.9 | 22 |

| Ornithine cyclodeaminase | HVO_2879 | 158 | 4 | 2.1 | 9.7 | 4.33 | 4.5 | 35.6 | 35 |

| Acyl-CoA dehydrogenase | HVO_A0092 | 192 | 6 | 2.1 | U | 4.84 | 4.8 | 41.4 | 55 |

| Amidohydrolase | HVO_A0095 | 267 | 6 | 2.1 | U | 4.67 | 4.7 | 28.8 | 35 |

| Translation elongation factor 1 α | HVO_0359 | 294 | 8 | 3.5 | 4.8 | 4.58 | 4.6 | 45.8 | 45 |

| Acetolactate synthase, small subunit (ilvN) | HVO_1507 | 279 | 5 | 3.5 | 4.6 | 4.83 | 4.9 | 23.7 | 37 |

| Transcription regulator (pspA) | HVO_2636 | 294 | 5 | 3.5 | 2.3 | 4.46 | 4.5 | 26.9 | 40 |

HVO GenBank no. corresponds to the putative ORF designation from this H. volcanii genome annotation.

Fold increase refers to increased protein abundance at either optimal (2.1 M) or high (3.5 M) salt as designated under sample. U, Unique protein spot.

The vast majority of proteins identified to be more abundant in the optimal- compared to high-salt medium were homologues of ribosomal proteins, enzymes linked to energy-generating or biosynthetic pathways, or proteins of unknown function. This result is consistent with the reduced doubling time (~twofold) and enhanced overall yield of cells grown on optimal- versus high-salt medium, respectively. The proteins identified as more abundant in high- versus optimal-salt medium included homologues of translation elongation factor 1α (EF1α), a regulatory subunit of acetolactate synthase (IlvN-like protein) and a transcriptional regulator related to the phage shock protein PspA. Not listed in Table 1 is HMG CoA reductase, which was found to display an approximately fourfold increase in expression under high-salt growth conditions, corroborating our previous findings (Bidle et al., 2007). It is also noteworthy that a recent survey of H. volcanii genes regulated by non-optimal high salinity via microarray analysis detected similar patterns of regulation compared with this proteomic analysis (C. Daniels, personal communication). Indeed, of the 18 proteins identified in this study, all but two ribosomal proteins (Hvo2553, Hvo2783) showed the same pattern of up- or down-regulation by salt compared with the microarray analysis.

Transcriptional characterization of pspA

To determine if H. volcanii pspA is transcriptionally regulated in response to changes in salinity, a qRT-PCR analysis was performed on RNA samples isolated from H. volcanii grown in optimal or high non-optimal NaCl conditions. A ~13-fold change was calculated in the relative level of expression of pspA in cells grown in 20 % NaCl compared with cells grown in 12 % NaCl. The relative expression level of pspA in cells grown in 20 % NaCl was 13.6±2.1-fold higher than cells grown in 12 % NaCl, as determined by the comparative critical threshold (2ΔΔCT ) method after normalization against 16S gene expression (Livak & Schmittgen, 2001). Given its integral role in sensing a variety of membrane stressors in bacteria (e.g. osmotic stress), these results suggest that pspA may play an important role in hypersaline adaptation in H. volcanii.

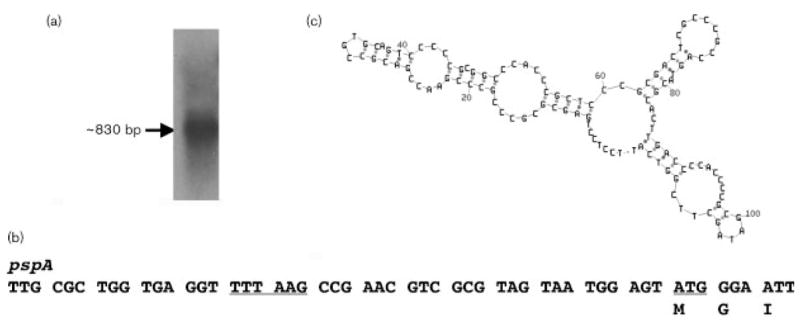

To resolve if pspA is transcribed as part of an operon, as is commonly the case in many bacteria, Northern analysis was performed. As shown in Fig. 1(a), a single transcript was resolved when probed with an internal pspA fragment. This transcript was ~830 bp, which corresponds to the size of the pspA gene. Directly downstream of pspA lies an ORF (Hvo2637) encoding a conserved hypothetical protein with predicted transmembrane-spanning helices, but no clear homology to any other proteins encoded within bacterial psp operons, namely pspBCDE. Indeed, a search of the H.volcanii genome indicates that there are no clear homologues of the other psp operon genes anywhere within the organism (Table 2). This suggests that the mechanism of PspA action in H. volcanii operates in a manner different from that seen in bacteria.

Fig. 1.

Northern analysis, promoter structure and secondary structure of pspA. (a) Northern analysis. Total RNA isolated from H. volcanii cells grown in 3.5 M NaCl medium was hybridized with a 32P-labelled probe made using a 500 bp internal H. volcanii pspA fragment. A single ~830 bp transcript hybridized with the probe. (b) Upstream sequence of pspA. The 6 bp putative archaeal promoter sequence (TTTAAG) located 19–24 bp upstream of the translational start site of pspA is underlined, as is the ATG start site. (c) Potential secondary structure occurring between the end of pspA and the start of Hvo2637. The predicted stability of this structure is calculated to be −35 kcal mol−1.

Table 2.

Phage shock protein (Psp) regulon components of E. coli conserved in H. volcanii and other Archaea Scores (bits) and E values are given in parentheses with the current annotation following. Homologues with E values greater than 0.075 are not included

| E. coli | Psp regulon components (protein/description) | HVO GenBank no.* | Closest archaeal homologue in GenBank |

|---|---|---|---|

| PspA | Transcriptional repressor of PspF under normal growth | HVO2636 (91, 5e-20) transcriptional regulator | HQ3029A (61.6, 8e-10) probable stress response protein |

| PspB | Cytoplasmic membrane protein of a PspC-PspB toxin-antitoxin pair; sequesters PspA from PspF during stress | None | None |

| PspC | Cytoplasmic membrane protein of a PspC-PspB toxin-antitoxin pair; sequesters PspA from PspF during stress | None (only low conservation in haloarchaea; see NP2464A) | MmarC7_0621 (40.8, 5e-04) phage shock protein C, PspC |

| PspD | Peripheral inner-membrane protein | None | None |

| PspE | Periplasmic protein related to thiosulfate sulfurtransferase | HVO2772 (39, 8e-05) hydrolase; HVO0024 (38, 1e-04) thiosulfate sulfurtransferase | MM_0350 (52.4, 1e-07) putative molybdopterin biosynthesis protein |

| PspF | AAA+ ATPase enhancer-binding protein; recruits σ54 to initiate transcription of the psp regulon | HVO0783 (39, 5e-04) Lon protease | PF0467 (45.1, 1e-04) Lon protease |

| PspG | Inner-membrane protein, appears to influence motility | HVO0686 (28, 7.5e-02) putative inner-membrane protein, conserved | TVN0494 (28.9, 1.7) Lon-type protease |

HVO ORF number according to H. volcanii genome database annotated by TIGR (April 2007 annotation; http://archaea.ucsc.edu/).

Further examination of the H. volcanii pspA sequence shows a clear archaeal consensus promoter (TTTAAG) located between 19 and 24 bp upstream of the translational start site of pspA (Fig. 1b). At the 3′ end of pspA, a short inverted repeat sequence can be found that may function as a transcription terminator. Indeed, bioinformatic analyses of the ~100 bp intergenic spacer region located between the pspA stop codon and the translational start site of Hvo2637 yielded ~20 different possible hairpin or secondary structure possibilities with stability coefficients (ΔG) ranging from ~ −30 to −35 kcal mol−1 (Fig. 1c).

Phylogenetic analysis of PspA across the three domains

A cursory bioinformatic search of completed archaeal genomes deposited in the GenBank database revealed that a number of euryarchaeota (e.g. methanogens and haloarchaea) encode homologues of PspA (see Fig. 2 for details). PspA is found ubiquitously in Gram-negative (e.g. Escherichia coli) bacteria as well as in Gram-positive (e.g. Bacillus cereus) bacteria and cyanobacteria (e.g. Synechococcus). It is widely hypothesized that a gene duplication of pspA within the cyanobacteria led to the formation of a similar gene, VIPP1, with a new-found function in thylakoid biogenesis. Indeed, photosynthesizing eukaryotes such as Arabidopsis all contain VIPP1 proteins and cyanobacteria contain a copy of both pspA and VIPP1. The distinguishing feature between the two proteins is the addition of a ~30 aa C-terminal extension on VIPP1 (Westphal et al., 2001).

Fig. 2.

Phylogenetic tree based on PspA and VIPP1 amino acid sequences from representatives of each domain of life constructed using maximum-likelihood analysis. Accession numbers for sequences used in construction of the tree can be found in Methods. Scale bar represents 5 aa substitutions per 100 aa.

A phylogenetic tree was constructed to determine the relationship of the H. volcanii PspA homologue to other known PspA/VIPP1 proteins. As seen in Fig. 2, the tree supports the close relationships between plant, bacterial and archaeal PspA/VIPP1 proteins. As expected, most groups cluster within their given domain of life; furthermore, the PspA/VIPP1 proteins from both photosynthetic groups, the prokaryotic cyanobacteria and eukaryotic plants, cluster within the same grouping, confirming their close evolutionary relationship. One unusual result was the inclusion of two bacterial PspA homologues within the archaeal methanogen cluster. Bootstrap values support this result with confidence between 80–90 %. Clearly, as more information is learned about how and why the Archaea use PspA, it will be of interest to determine whether or not these two bacterial genera, Moorella and Propionibacterium, follow a similar mechanistic strategy as the Archaea.

Both the E. coli PspA and A. thaliana VIPP1 proteins share approximately 27 % identity and 53 % similarity with the H. volcanii PspA protein. To determine whether or not these proteins shared any discernible cross-reactivity to the H. volcanii protein, Western analyses were performed with both anti-E. coli PspA and anti-A. thaliana VIPP1 antibodies [generous gifts from J. Tommassen (Utrecht, The Netherlands) and U. Vothknecht (Munich, Germany), respectively]. No significant cross-reactivity was detected with either antibody tested (data not shown). These results are not entirely surprising as our evidence suggests it is likely that the H. volcanii PspA functions in a very different manner than either of the other domains of life.

DISCUSSION

The H. volcanii proteome was examined by 2-DE and MS/MS to identify proteins of differential abundance under two different salinities (optimal versus high salt). Among the protein isoforms identified to be more abundant in high salt was a homologue to a known bacterial transcriptional activator, PspA. PspA plays an integral role in sensing a variety of membrane stressors in bacteria (e.g. osmotic stress). Thus, these results suggest that PspA may play an important role in hypo- and/or hypersaline adaptation in haloarchaea such as H. volcanii. Indeed, pspA-specific transcript levels were found to be regulated by hypersalinity compared with optimal growth conditions, a result that has also been independently confirmed by recent microarray analysis (C. Daniels, personal communication).

The presence of pspA in euryarchaeal genomes is widespread as shown by its inclusion in a wide range of haloarchaea and methanogen genomes sequenced to date with the exception of the extreme haloarchaeon Halobacterium sp. NRC-1, which does not appear to contain an annotated pspA homologue in its genome. Beyond PspA, few, if any, of the E. coli psp regulon components are highly conserved among Archaea (see Table 2). The closest relatives of PspE include ORFs annotated as hydrolase, thiosulfate sulfurtransferase and/or molybdopterin biosynthetic enzymes. Likewise, among archaeal proteins, PspF is most closely related to the membrane-associated Lon protease of the AAA+ superfamily (Besche et al., 2004; Besche & Zwickl, 2004). Although PspC annotated homologues are present in Archaea, these are not highly conserved or widespread. Furthermore, unlike bacteria which use σ factors for promoter binding and transcription initiation, Archaea require eukaryotic-like transcription initiation factors (e.g. TATA-binding proteins and transcription factor B) which in turn recruit a multisubunit, complex RNA polymerase to initiate transcription (reviewed by Baumann et al., 1995; Bell & Jackson, 1998; Kyrpides & Ouzounis, 1999; Langer et al., 1995; Soppa, 1999; Thomm, 1996). Thus, the mechanism of how the H. volcanii PspA responds to osmotic stress and the members of the psp regulon are likely to differ greatly from the E. coli paradigm. Clearly, the role of PspA in Archaea remains to be determined.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the NSF to K. A. B. (MCB-0641243), and the DOE (DE-FG02-05ER15650) and NIH (2R01 GM57498-06) to J. A. M.-F. Kay D. Bidle is thanked for helpful discussions regarding the qRT-PCR analysis.

Abbreviations

- 2-DE

two-dimensional gel electrophoresis

- MS/MS

tandem mass spectrometry

- qRT-PCR

quantitative real-time PCR

References

- Baumann P, Qureshi SA, Jackson SP. Transcription: new insights from studies on Archaea. Trends Genet. 1995;11:279–283. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(00)89075-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell SD, Jackson S. Transcription and translation in archaea: a mosaic of eukaryal and bacterial features. Trends Microbiol. 1998;6:222–228. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(98)01281-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergler H, Abraham H, Aschauer H, Turnowsky F. Inhibition of lipid biosynthesis induces the expression of the pspA gene. Microbiology. 1994;140:1937–1944. doi: 10.1099/13500872-140-8-1937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Besche H, Zwickl P. The Thermoplasma acidophilum Lon protease has a Ser-Lys dyad active site. Eur J Biochem. 2004;271:4361–4365. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.2004.04421.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Besche H, Tamura N, Tamura T, Zwickl P. Mutational analysis of conserved AAA+ residues in the archaeal Lon protease from Thermoplasma acidophilum. FEBS Lett. 2004;574:161–166. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bidle KA. Differential expression of genes influenced by changing salinity using RNA arbitrarily primed PCR in the archaeal halophile, Haloferax volcanii. Extremophiles. 2003;7:1–7. doi: 10.1007/s00792-002-0289-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bidle KA, Hanson TE, Howell K, Nannen J. HMG-CoA reductase is regulated by salinity at the level of transcription in Haloferax volcanii. Extremophiles. 2007;11:49–55. doi: 10.1007/s00792-006-0008-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brissette JL, Russel M, Weiner L, Model P. Phage shock protein, a stress protein of Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87:862–866. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.3.862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brissette JL, Weiner L, Ripmaster TL, Model P. Characterisation and sequence of the Escherichia coli stress-induced psp operon. J Mol Biol. 1991;220:35–48. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(91)90379-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniels CJ, McKee AHZ, Doolittle WF. Archaebacterial heat-shock proteins. EMBO J. 1984;3:745–749. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1984.tb01878.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darwin AJ. The phage-shock-protein response. Mol Microbiol. 2005;57:621–628. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04694.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLisa MP, Lee P, Palmer T, Georgiou G. Phage shock protein PspA of Escherichia coli relieves saturation of protein export via the Tat pathway. J Bacteriol. 2004;186:366–373. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.2.366-373.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis PP, Shimmin LC. Evolutionary divergence and salinity-mediated selection in halophilic Archaea. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1997;61:90–104. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.61.1.90-104.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrer C, Mojica FJM, Juez G, Rodriguez-Valera F. Differentially transcribed regions of Haloferax volcanii genome depending on the medium salinity. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:309–313. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.1.309-313.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasteiger E, Jung E, Bairoch A. SWISS-PROT: connecting biomolecular knowledge via a protein database. Curr Issues Mol Biol. 2001;3:47–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant WD, Gemmell RT, McGenity TJ. Halophiles. In: Horikoshi K, Grant WD, editors. Extremophiles: Microbial Life in Extreme Environments. New York: Wiley and Sons Inc; 1998. pp. 93–132. [Google Scholar]

- Hankamer BD, Elderkin SL, Buck M, Nield J. Organization of the AAA(+) adaptor protein PspA is an oligomeric ring. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:8862–8866. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307889200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izotova LS, Strongin AY, Sterkin VE, Ostoslavaskaya VI, Lyublinskaya LA, Timokhina EA, Stepanov VM. Purification and properties of serine protease from Halobacterium halobium. J Bacteriol. 1983;155:826–830. doi: 10.1128/jb.155.2.826-830.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Javor B. Hypersaline Environments: Microbiology and Biogeochemistry. Berlin: Springer Verlag; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Jovanovic G, Weiner L, Model P. Identification, nucleotide sequence, and characterization of PspF, the transcriptional activator of the Escherichia coli stress-induced psp operon. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:1936–1945. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.7.1936-1945.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkland PA, Busby J, Stevens S, Maupin-Furlow JA. Trizol-based method for sample preparation and isoelectric focusing of halophilic proteins. Anal Biochem. 2006;351:254–259. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2006.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkland PA, Reuter CJ, Maupin-Furlow JA. Effect of proteasome inhibitor clasto-lactacystin-β-lactone on the proteome of the haloarchaeon Haloferax volcanii. Microbiology. 2007;153:2271–2280. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2007/005769-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleerebezem M, Tommassen J. Expression of the pspA gene stimulates efficient protein export in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 1993;7:947–956. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01186.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleerebezem M, Crielaard W, Tommassen J. Involvement of the stress protein PspA (phage shock protein A) of Escherichia coli in maintenance of the proton motive force under stress conditions. EMBO J. 1996;15:162–171. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyrpides NC, Ouzounis CA. Transcription in Archaea. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:8545–8550. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.15.8545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langer D, Hain J, Thuriaux P, Zillig W. Transcription in Archaea: similarity to that in Eucarya. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:5768–5772. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.13.5768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2ΔΔCT method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madern D, Ebel C, Zaccai G. Halophilic adaptation of enzymes. Extremophiles. 2000;4:91–98. doi: 10.1007/s007920050142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mojica FJM, Cisneros E, Ferrer C, Rodriguez-Valera F, Juez G. Osmotically induced response in representatives of halophilic prokaryotes: the bacterium Halomonas elongata and the archeon Haloferax volcanii. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:5471–5481. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.17.5471-5481.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullakhanbhai MF, Larsen H. Halobacterium volcanii spec. nov., a Dead Sea halobacterium with a moderate salt requirement. Arch Microbiol. 1975;104:207–214. doi: 10.1007/BF00447326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oren A. Microbiology and Biogeochemistry of Hypersaline Environments. CRC Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Oren A. Bioenergetic aspects of halophilism. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1999;63:334–348. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.63.2.334-348.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrière G, Gouy M. WWW-Query: an on-line retrieval system for biological sequence banks. Biochimie. 1996;78:364–369. doi: 10.1016/0300-9084(96)84768-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robb FT, Place AR, Sowers KR, Schreier HJ, DasSarma S, Fleischmann EM. Archaea: a Laboratory Manual. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson JL, Pyzyna B, Atrasz RG, et al. Growth kinetics of extremely halophilic Archaea (family Halobacteriaceae) as revealed by Arrhenius plots. J Bacteriol. 2005;187:923–925. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.3.923-929.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowley G, Spector M, Kormanec J, Roberts M. Pushing the envelope: extracytoplasmic stress responses in bacterial pathogens. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2006;4:383–394. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soppa J. Transcription initiation in Archaea: facts, factors, and future aspects. Mol Microbiol. 1999;31:1295–1305. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01273.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomm M. Archaeal transcription factors and their role in transcription initiation. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1996;18:159–171. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.1996.tb00234.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson JD, Gibson TJ, Plewniak F, Jeanmougin F, Higgins DG. The CLUSTAL_X window interface: flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:4876–4882. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.24.4876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiner L, Model P. Role of an Escherichia coli stress-response operon in stationary-phase survival. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:2191–2195. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.6.2191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiner L, Brissette JL, Model P. Stress-induced expression of the Escherichia coli phage shock protein operon is dependent on sigma 54 and modulated by positive and negative feedback mechanisms. Genes Dev. 1991;5:1912–1923. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.10.1912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wendoloski D, Ferrer C, Dyall-Smith ML. A new simvastatin (mevinolin)-resistance marker from Haloarcula hispanica and a new Haloferax volcanii strain cured of plasmid pHV2. Microbiology. 2001;147:959–964. doi: 10.1099/00221287-147-4-959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westphal S, Heins L, Soll J, Vothknecht UC. Vipp1 deletion mutant of Synechocystis: a connection between bacterial phage shock and thylakoid biogenesis? Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:4243–4248. doi: 10.1073/pnas.061501198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]