Abstract

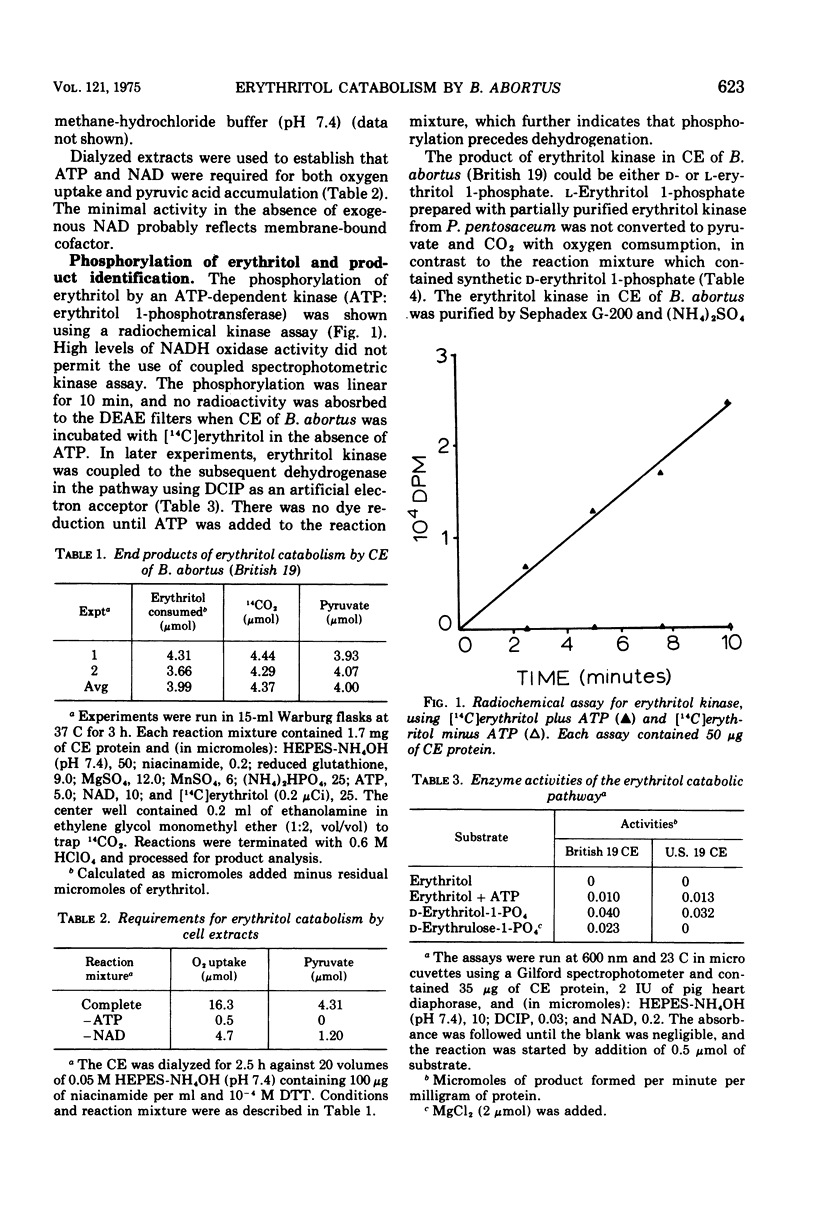

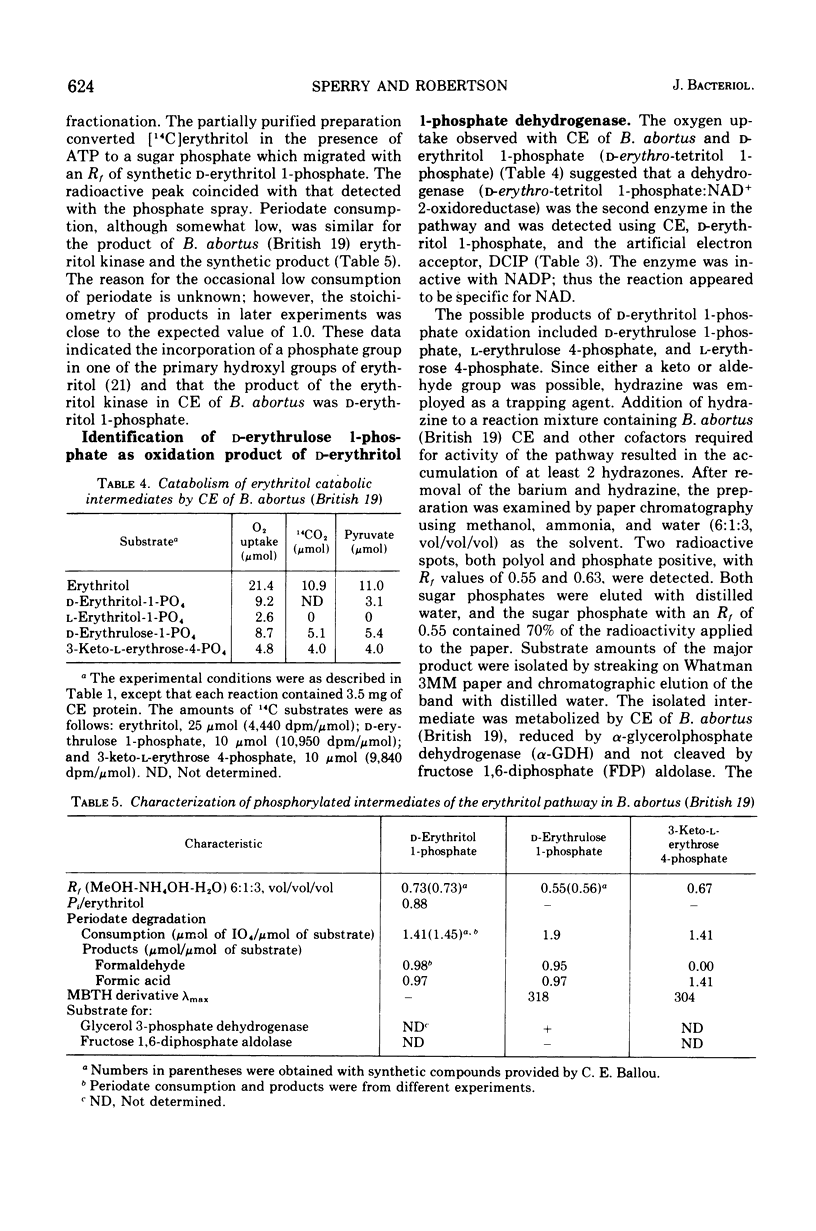

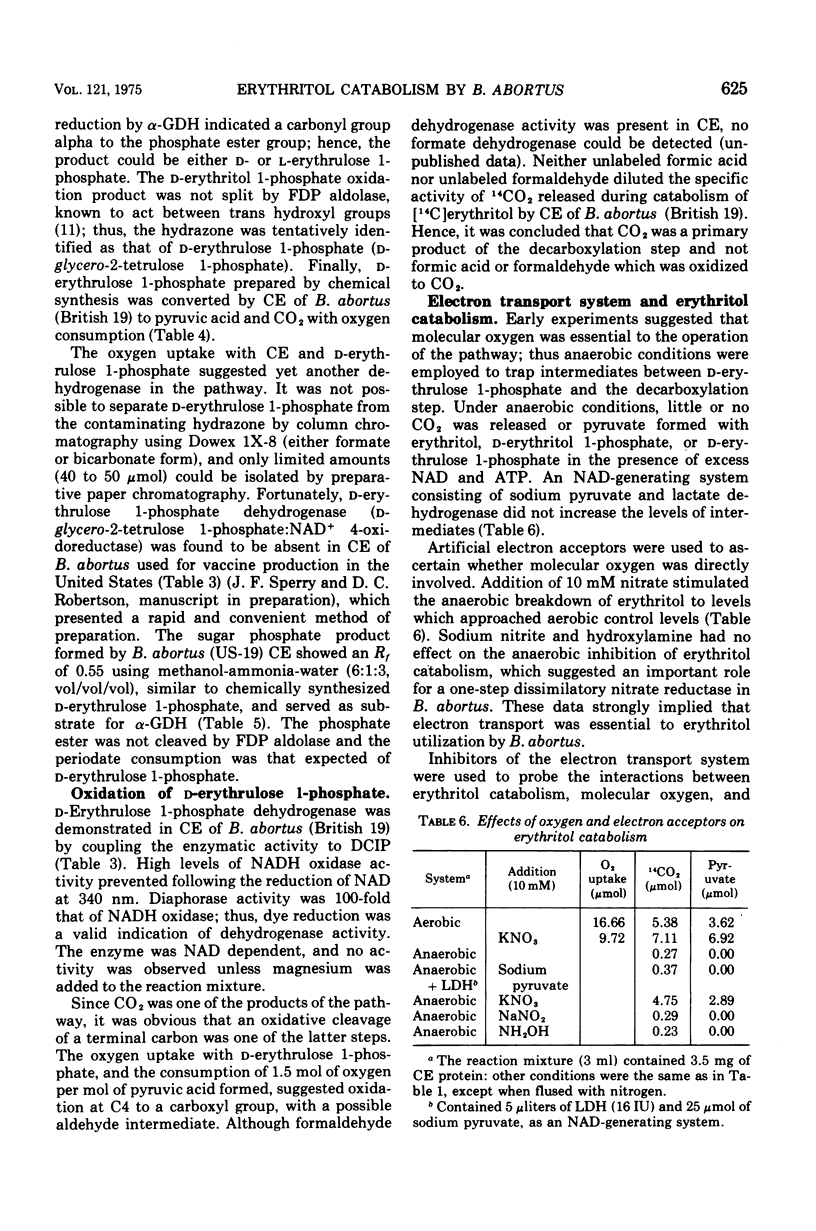

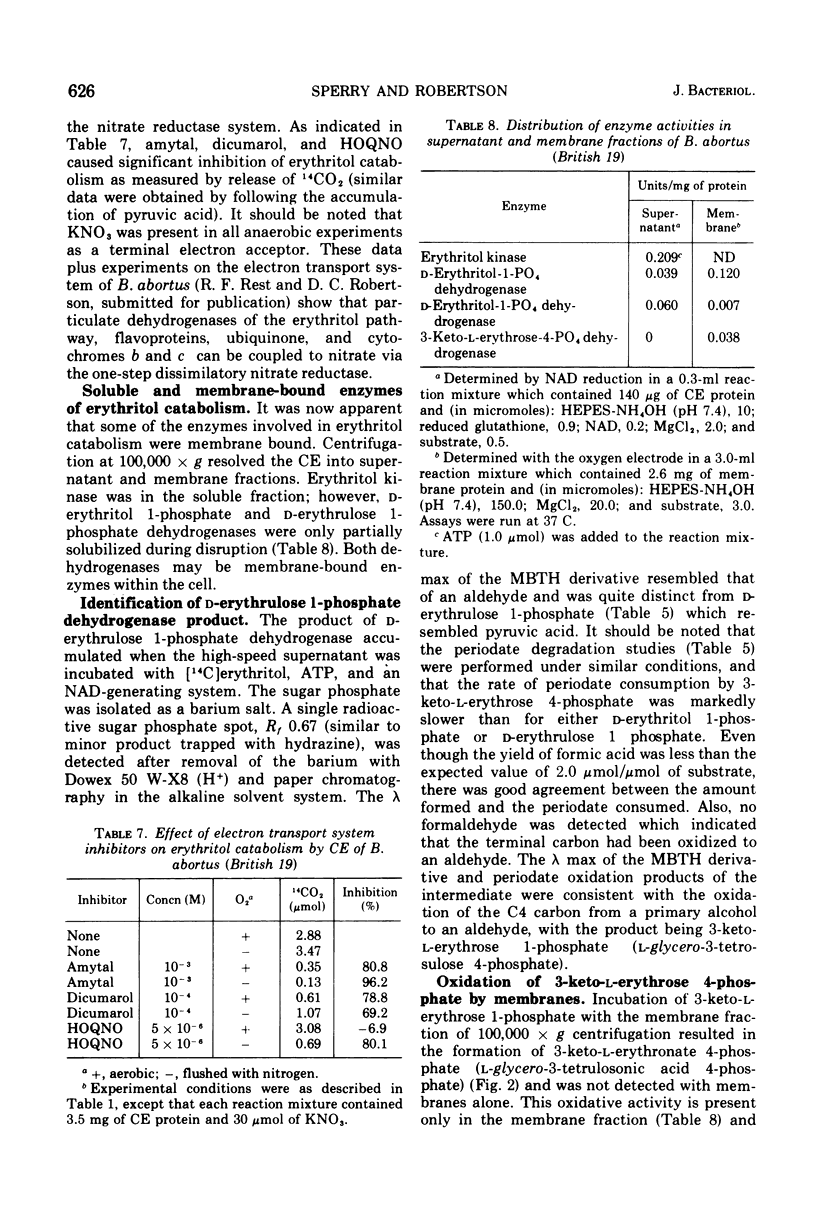

Cell extracts of Brucella abortus (British 19) catabolized erythritol through a series of phosphorylated intermediates to dihydroxyacetonephosphate and CO-2. Cell extracts required adenosine 5'-triphosphate (ATP), nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD), Mg2+, inorganic orthophosphate, and reduced glutathione for activity. The first reaction in the pathway was the phosphorylation of mesoerythritol with an ATP-dependent kinase which formed d-erythritol 1-phosphate (d-erythro-tetritol 1-phosphate). d-Erythritol 1-phosphate was oxidized by an NAD-dependent dehydrogenase to d-erythrulose 1-phosphate (d-glycero-2-tetrulose 1-phosphate). B. abortus (US-19) was found to lack the succeeding enzyme in the pathway and was used to prepare substrate amounts of d-erythrulose 1-phosphate. d-Erythritol 1-phosphate dehydrogenase (d-erythro-tetritol 1-phosphage: NAD 2-oxidoreductase) is probably membrane bound. d-Erythrulose 1-phosphate was oxidized by an NAD-dependent dehydrogenase to 3-keto-l-erythrose 4-phosphate (l-glycero-3-tetrosulose 4-phosphate) which was further oxidized at C-1 by a membrane-bound dehydrogenase coupled to the electron transport system. Either oxygen or nitrate had to be present as a terminal electron acceptor for the oxidation of 3-keto-l-erythrose 4-phosphate to 3-keto-l-erythronate 4-phosphate (l-glycero-3-tetrulosonic acid 4-phosphate). The beta-keto acid was decarboxylated by a soluble decarboxylase to dihydroxyacetonephosphate and CO-2. Dihydroxyacetonephosphate was converted to pyruvic acid by the final enzymes of glycolysis. The apparent dependence on the electron transport system of erythritol catabolism appears to be unique in Brucella and may play an important role in coupling metabolism to active transport and generation of ATP.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- ANDERSON J. D., SMITH H. THE METABOLISM OF ERYTHRITOL BY BRUCELLA ABORTUS. J Gen Microbiol. 1965 Jan;38:109–124. doi: 10.1099/00221287-38-1-109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ANDERSON R. L., WOOD W. A. Pathway of L-xylose and L-lyxose degradation in Aerobacter aerogenes. J Biol Chem. 1962 Feb;237:296–303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BANDURSKI R. S., AXELROD B. The chromatographic identification of some biologically important phosphate esters. J Biol Chem. 1951 Nov;193(1):405–410. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun M. L., Niederpruem D. J. Erythritol metabolism in wild-type and mutant strains of Schizophyllum commune. J Bacteriol. 1969 Nov;100(2):625–634. doi: 10.1128/jb.100.2.625-634.1969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HOLTEN D., FROMM H. J. Purification and properties of erythritol kinase from Propionibacterium pentosaceum. J Biol Chem. 1961 Oct;236:2581–2584. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harold F. M. Conservation and transformation of energy by bacterial membranes. Bacteriol Rev. 1972 Jun;36(2):172–230. doi: 10.1128/br.36.2.172-230.1972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartman F. C. Haloacetol phosphates. Potential active-site reagents for aldolase, triose phosphate isomerase, and glycerophosphate dehydrogenase. I. Preparation and properties. Biochemistry. 1970 Apr 14;9(8):1776–1782. doi: 10.1021/bi00810a017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JAKOBY W. B., FREDERICKS J. Erythritol dehydrogenase from Aerobacter aerogenes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1961 Mar 18;48:26–32. doi: 10.1016/0006-3002(61)90511-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JONES L. M., MONTGOMERY V., WILSON J. B. CHARACTERISTICS OF CARBON DIOXIDE-INDEPENDENT CULTURES OF BRUCELLA ABORTUS ISOLATED FROM CATTLE VACCINATED WITH STRAIN 19. J Infect Dis. 1965 Jun;115:312–320. doi: 10.1093/infdis/115.3.312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KALNITSKY G., TAPLEY D. F. A sensitive method for estimation of oxaloacetate. Biochem J. 1958 Sep;70(1):28–34. doi: 10.1042/bj0700028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KEPPIE J., WILLIAMS A. E., WITT K., SMITH H. THE ROLE OF ERYTHRITOL IN THE TISSUE LOCALIZATION OF THE BRUCELLAE. Br J Exp Pathol. 1965 Feb;46:104–108. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCULLOUGH N. B., BEAL G. A. Growth and manometric studies on carbohydrate utilization of Brucella. J Infect Dis. 1951 Nov-Dec;89(3):266–271. doi: 10.1093/infdis/89.3.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer M. E. Metabolic characterization of the genus Brucella. V. Relationship of strain oxidation rate of i-erythritol to strain virulence for guinea pigs. J Bacteriol. 1966 Sep;92(3):584–588. doi: 10.1128/jb.92.3.584-588.1966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer M. E. Metabolic characterization of the genus Brucella. VI. Growth stimulation by i-erythritol compared with strain virulence for guinea pigs. J Bacteriol. 1967 Mar;93(3):996–1000. doi: 10.1128/jb.93.3.996-1000.1967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newsholme E. A., Robinson J., Taylor K. A radiochemical enzymatic activity assay for glycerol kinase and hexokinase. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1967 Mar 15;132(2):338–346. doi: 10.1016/0005-2744(67)90153-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PAZ M. A., BLUMENFELD O. O., ROJKIND M., HENSON E., FURFINE C., GALLOP P. M. DETERMINATION OF CARBONYL COMPOUNDS WITH N-METHYL BENZOTHIAZOLONE HYDRAZONE. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1965 Mar;109:548–559. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(65)90400-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson D. C., McCullough W. G. The glucose catabolism of the genus Brucella. I. Evaluation of pathways. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1968 Sep 20;127(1):263–273. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(68)90225-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson D. C., McCullough W. G. The glucose catabolism of the genus Brucella. II. Cell-free studies with B. abortus (S-19). Arch Biochem Biophys. 1968 Sep 20;127(1):445–456. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(68)90249-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose I. A., O'Connell E. L. Inactivation and labeling of triose phosphate isomerase and enolase by glycidol phosphate. J Biol Chem. 1969 Dec 10;244(23):6548–6550. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SMITH H., ANDERSON J. D., KEPPIE J., KENT P. W., TIMMIS G. M. THE INHIBITION OF THE GROWTH OF BRUCELLAS IN VITRO AND IN VIVO BY ANALOGUES OF ERYTHRITOL. J Gen Microbiol. 1965 Jan;38:101–108. doi: 10.1099/00221287-38-1-101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SMITH H., WILLIAMS A. E., PEARCE J. H., KEPPIE J., HARRIS-SMITH P. W., FITZ-GEORGE R. B., WITT K. Foetal erythritol: a cause of the localization of Brucella abortus in bovine contagious abortion. Nature. 1962 Jan 6;193:47–49. doi: 10.1038/193047a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slotnick I. J., Dougherty M. Erythritol as a selective substrate for the growth of Serratia marcescens. Appl Microbiol. 1972 Aug;24(2):292–293. doi: 10.1128/am.24.2.292-293.1972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tepper B. S. Differences in the utilization of glycerol and glucose by Mycobacterium phlei. J Bacteriol. 1968 May;95(5):1713–1717. doi: 10.1128/jb.95.5.1713-1717.1968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WILLIAMS A. E., KEPPIE J., SMITH H. The chemical basis of the virulence of Brucella abortus. III. Foetal erythritol a cause of the localisation of Brucella abortus in pregnant cows. Br J Exp Pathol. 1962 Oct;43:530–537. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wawszkiewicz E. J., Barker H. A. Erythritol metabolism by Propionibacterium pentosaceum. The over-all reaction sequence. J Biol Chem. 1968 Apr 25;243(8):1948–1956. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]