Abstract

We report here a system with which a correctly folded complete protein and its encoding mRNA both remain attached to the ribosome and can be enriched for the ligand-binding properties of the native protein. We have selected a single-chain fragment (scFv) of an antibody 108-fold by five cycles of transcription, translation, antigen-affinity selection, and PCR. The selected scFv fragments all mutated in vitro by acquiring up to four unrelated amino acid exchanges over the five generations, but they remained fully compatible with antigen binding. Libraries of native folded proteins can now be screened and made to evolve in a cell-free system without any transformation or constraints imposed by the host cell.

Evolutionary methods may bring refinement to protein engineering that is beyond the powers and accuracy of rational design today. Evolution can be defined as a succession of “generations,” cycles of genetic diversification, followed by Darwinian selection for a desired phenotypic property. In classic experiments, nucleic acids have evolved and been selected for physical properties (1) in vitro, and in this case, the substance conferring the phenotype was identical to the genetic material. Oligonucleotide ligands, usually single-stranded RNA, have been identified for many targets by SELEX (2, 3), in which a synthetic DNA library is transcribed, and the RNA is selected for binding, reverse transcribed, and amplified over several rounds. However, all experiments with proteins as the carrier of the phenotype, clearly of much broader applicability, have so far relied on living cells for effecting the coupling between gene and protein, either directly or by the production of phages or viruses (4), since no in vitro method to link phenotype and genotype has been available for native proteins.

Since the DNA library as the information carrier for encoded protein diversity has to be transformed or transfected into bacterial or eukaryotic cells, the available diversity is severely limited by the low efficiency of DNA uptake (5). Furthermore, in each generation, the DNA library has to be first ligated into a replicatable genetic package, a process in which diversity is again decreased. Finally, many promising variants may be selected against in the host environment. Only a few studies (6) have carried protein optimization through more than one generation by using methods such as phage display, since this requires repeatedly switching between in vitro diversification and in vivo screening—a laborious process.

A series of studies have shown that specific mRNAs can be enriched by immunoprecipitation of polysomes (7–9). Recently, Mattheakis and co-workers (10) reported an affinity selection of a short peptide from a library by using polysomes, to connect genotype and phenotype in vitro.

We used Mattheakis’ concept to develop a system that is compatible with the folding of whole proteins to their native structure on the ribosome, introducing a series of new features which proved to be essential to make the system efficient enough for whole proteins (Fig. 1). Since the protein can assume its native three-dimensional structure only after it is completely synthesized, the translation has to go to the very end of the mRNA, and only the last few ribosomes on the mRNA can be expected to contain native protein able to bind to the ligand. We show here that an scFv single-chain fragment of an antibody, which requires its correctly assembled three-dimensional structure to bind the antigen (a hydrophilic peptide), can be enriched 108-fold by ribosome display, and its sequence “evolves” during the process

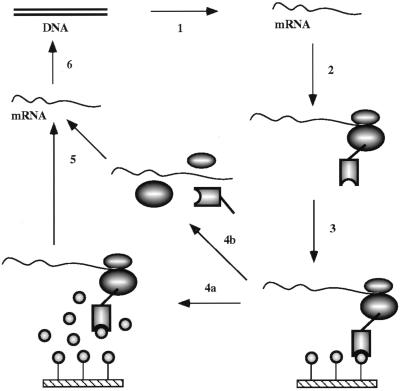

Figure 1.

Principle of in vitro ribosome display for screening native protein (scFv) libraries for ligand (antigen) binding. Step 1, a DNA scFv library is first amplified by PCR, whereby a T7 promoter, ribosome-binding site, and stem–loops are introduced, and then transcribed to RNA. Step 2, after purification, mRNA is translated in vitro in an Escherichia coli S-30 system in the presence of different factors enhancing the stability of ribosomal complexes and improving the folding of the scFv antibodies on the ribosomes. Translation is stopped by cooling on ice, and the ribosome complexes are stabilized by increasing the magnesium concentration. Step 3, the desired ribosome complexes are affinity selected from the translation mixture by binding of the native scFv to the immobilized antigen. Unspecific ribosome complexes are removed by intensive washing. Step 4, the bound ribosome complexes can then be dissociated by EDTA (step 4b), or whole complexes can be specifically eluted with antigen (step 4a). Step 5, RNA is isolated from the complexes. Step 6, isolated mRNA is reverse transcribed to cDNA, and cDNA is then amplified by PCR. This DNA is then used for the next cycle of enrichment, and a portion can be analyzed by cloning and sequencing and/or by ELISA or RIA.

METHODS

Construction of scFv Antibody Fragments.

The anti-hemagglutinin scFv (scFvhag) construct c7 was amplified by PCR in two steps from an fd phage displaying the scFv 17/9 (11, 12) containing a (Gly4Ser)3 linker, using in the first step oligonucleotides ON1 (5′-TTTCCCGAATTGTGAGCGGATAACAATAGAAATAATTTTGTTTAACTTTAAGAAGGAGATATATCCATGGACTACAAAGA-3′), which introduces a ribosome-binding site, and ON2 (5′-TTTAAGCAGCTCGATAGCAGCAC-3′). In the second step ON3 (5′-ATATATGTCGACGAAATTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGAGACCACAACGGTTTCCCGAATTGTG-3′), which introduces the T7 promoter and the 5′-loop, and ON4 (5′-AGACCCGTTTAGAGGCCCCAAGGGGTTATGGAATTCACCTTTAAGCAGCTC-3′), which introduces a modified lipoprotein terminator (lpp term) loop with stop codon removed, were used. The spacer, fused C-terminally to the scFv, is derived from amino acids 211–299 of gene III of filamentous phage M13 mp19 (12), and the translated lpp term adds another 24 amino acids.

The other constructs were prepared by PCR from c7 using the following primer pairs: c1, ON5 (5′-TCAGTAGCGACAGAATCAAG-3′) and ON6 (5′-GAAATTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGTTAACTTTAGAAGGAGGTATATCCATGGACTACAAAGA-3′), which introduces the T7 promoter and ribosome-binding site without the 5′-stem–loop, the spacer is derived from amino acids 211–294 of gene III; c2, ON4 and ON6, the same spacer as c7; c3, ON6 and ON7 (5′-GGCCCACCCGTGAAGGTGAGCCTCAGTAGCGACAG-3′), the spacer is derived from amino acids 211–294 of gene III following 7 amino acids of the translated early terminator of phage T3 (T3Te); c4, ON3 and ON5, the same spacer as c1; c5, ON3 and ON7, the same spacer as c3; c6, ON2 and ON3, and a spacer derived from amino acids 211–299 of gene III following the first 4 amino acids of lpp term; c8, ON3 and ON8 (5′-TTTAAGCAGCTCATCAAAATCACC-3′), and a spacer derived from amino acids 211–264 of gene III following the first 4 amino acids of lpp term; c9, ON3 and ON4, and a spacer derived from amino acids 211–264 of gene III following 24 amino acids of lpp term, using construct c8 as a template.

The anti-β-lactam scFvAL2 construct [VL-(Gly4Ser)4-VH] was amplified by PCR in two steps from plasmid pAK202 (13), using in the first step oligonucleotides ON1 and ON7 and in the second step ON3 and ON7. The spacer is derived from amino acids 240–294 of gene III of filamentous phage M13 mp19 (13), and the translated T3Te adds another 7 amino acids.

Northern Analysis.

RNA electrophoresis and transfer to a Nytran membrane (Schleicher & Schuell) were carried out as described (14) with a Turboblotter (Schleicher & Schuell). Hybridization was performed for 12 hr at 60°C (15). Hybridization was carried out with the oligonucleotide ON9 (5′-ACATGGTAACTTTTTCACCAGCGGTAACGG-3′), which anneals to the VL region of scFvhag mRNA. This oligonucleotide was labeled by 3′ tailing with digoxigenin-11-dUTP/dATP by using the DIG Oligonucleotide Tailing Kit (Boehringer Mannheim). Washing conditions were as follows: 2× SSC/0.5% SDS for 5 min at room temperature; 2× SSC/0.5% SDS twice for 30 min at 60°C; and 0.1× SSC for 10 min at room temperature. The hybridized oligonucleotide probe was detected by using the DIG DNA Labeling and Detection Kit with the chemiluminescent substrate CSPD (Boehringer Mannheim) and exposure to x-ray film, or with the fluorimetric substrate AttoPhos (Boehringer Mannheim) and analysis using a fluoroimager (Molecular Dynamics).

In Vitro Translation of scFv Antibody Fragments.

In vitro translation in an E. coli S-30 system was performed according to Chen and Zubay (16) with several modifications. Translation was carried out for 10 min at 37°C in a 110-μl reaction mixture that contained the following components: 50 mM Tris⋅HOAc at pH 7.5, 30 mM NH4OAc, 12.3 mM Mg(OAc)2, 0.35 mM each amino acid, 2 mM ATP, 0.5 mM GTP, 1 mM cAMP, 0.5 mg/ml E. coli tRNA, 20 μg/ml folinic acid, 100 mM KOAc, 30 mM acetylphosphate (17), 1.5% polyethylene glycol 8000, 33 μg/ml rifampicin, 1 mg/ml vanadyl ribonucleoside complexes (VRC), 23 μl of E. coli MRE600 extract (16), and 90 μg/ml mRNA.

Affinity Selection of Ribosome Complexes and Isolation of RNA.

The translation was stopped by adding Mg(OAc)2 to a final concentration of 50 mM and cooling on ice (18). The samples were diluted 4-fold with ice-cold washing buffer [50 mM Tris⋅HOAc, pH 7.5/150 mM NaCl/50 mM Mg(OAc)2/0.1% Tween 20] and centrifuged for 5 min at 4°C at 10,000 × g to remove insoluble components. Microtiter plates coated with hemagglutinin-transferrin conjugate were prewashed with ice-cold washing buffer, and the supernatant from the centrifuged translation mixture was applied (200 μl per microtiter well) and the plate was gently shaken for 1 hr in the cold room. After five washes with ice-cold washing buffer, the retained ribosome complexes were dissociated with ice-cold elution buffer (100 μl per well; 50 mM Tris⋅HOAc at pH 7.5/150 mM NaCl/10 mM EDTA/50 μg/ml E. coli tRNA) for 10 min in the cold room, and released mRNA was recovered by precipitation with ethanol or by isolation using the Rneasy kit (Qiagen).

Reverse Transcription–PCR and in Vitro Transcription.

Reverse transcription was performed using Superscript reverse transcriptase (GIBCO/BRL) according to the supplier’s recommendation. PCR was performed using Taq DNA polymerase (GIBCO/BRL) in the presence of 5% (vol/vol) dimethyl sulfoxide (4 min at 94°C, followed by 3 cycles of 30 sec at 94°C, 30 sec at 37°C, and 2 min at 72°C, followed by 10 similar cycles at 60°C instead of 37°C, 20 similar cycles at 60°C instead of 37°C with elongation at 72°C prolonged by 15 sec per cycle and finished by 10 min at 72°C). PCR products were analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis and purified from the gel and reamplified, if the amount and quality was not sufficient, or directly used for transcription without additional purification. In vitro transcription was performed as described (19).

In Vitro Coupled Transcription–Translation and RIA.

After the fifth round of ribosome display, PCR products were cloned into the vector pTFT74 (20). In vitro coupled transcription–translation in the S-30 E. coli system was performed using 50 μg/ml plasmid DNA and conditions similar to those described above with the following modifications. A coupled transcription–translation was carried out for 30 min at 37°C, and the reaction mixture was supplemented with T7 RNA polymerase at 2000 units/ml and 0.5 mM UTP and TTP. The mixture contained [35S]methionine at 50 μCi/ml (1 μCi = 37 kBq) and each amino acid except methionine at 0.35 mM. After translation, the reaction mixture was diluted 4-fold with PBS and bound to immobilized hemagglutinin peptide in a microtiter well. After 60 min of incubation with gentle shaking, microtiter wells were washed five times with PBS containing 0.1% Tween 20, and bound radioactive protein was eluted with 0.1 M triethylamine. Eluted protein was quantified in a scintillation counter.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Model System and Quantification of Yields of Affinity Selection.

As a model system, we used scFv fragments of antibodies (21), in which the variable domain of the light chain (VL) is connected by means of a flexible linker to the variable domain of the heavy chain (VH). To tether the folded protein to the ribosome and not interfere with folding we fused a spacer to the C terminus of the scFv fragment. Since the antibody domains must form disulfide bonds, and the RNA polymerase requires 2-mercaptoethanol for maximal stability, we performed transcription in a separate reaction and optimized the conditions for oxidative protein folding during translation (22) (see below).

Polypeptide release is an active process, requiring three polypeptide release factors in E. coli (23–25) and one ribosome recycling factor which releases the mRNA (26). The consequence of release factor binding is normally the hydrolysis of the peptidyl-tRNA between the ribose and the last amino acid by the peptidyltransferase center of the ribosome (25). Our system is devoid of stop codons, and thus a fraction of the polypeptide may not be hydrolyzed off the tRNA and remain attached to the ribosome and thus be available for affinity selection.

Translation is stopped by cooling on ice, and the ribosome complexes are further stabilized against dissociation by 50 mM magnesium acetate (18). Chloramphenicol at 50 μM, assumed to also induce ribosome stalling (10, 27), did not improve the selection properties (data not shown). The whole complex, consisting of synthesized protein, ribosome, and mRNA was then bound to the affinity matrix, washed, and eluted with competing ligand, or the ribosomes were dissociated with EDTA (Fig. 1). We did not find it necessary to preparatively isolate polysomes at any stage. The efficiency of ribosome display was found to be two orders of magnitude lower when using coupled in vitro transcription–translation (data not shown).

We developed the ribosome display system in two stages, first by engineering the gene structure for in vitro transcription, translation, and folding, then by optimizing the translation reaction itself. Each test started with 10 μg of input mRNA; this corresponds to ≈1.5 × 1013 molecules. The input mRNA was subjected to a single round of affinity selection: translation in vitro, capture of ribosome complexes on immobilized target ligand, and release of mRNA. The released mRNA was then quantified by Northern analysis.

Effect of mRNA Structure on Yield.

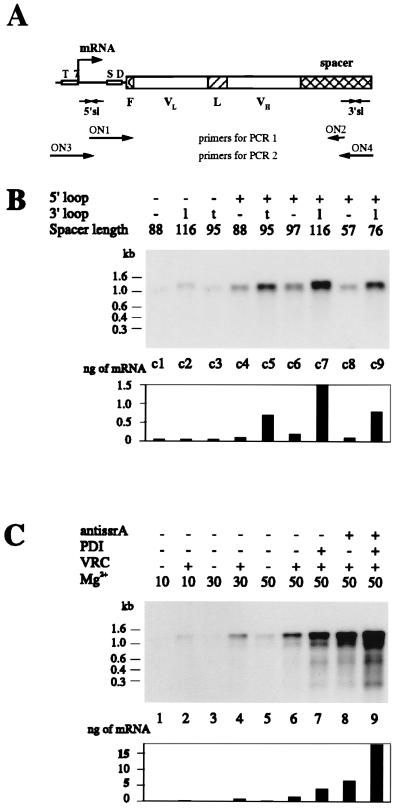

In designing the ribosome display system, we first engineered the flanking regions of the scFv gene (Fig. 2A). The gene must be transcribed very efficiently from the PCR product, and its mRNA must be stable against nucleases. For the 5′ end, we used the T7 promoter and the natural T7 gene 10 upstream region, which encodes a stem–loop structure directly at the beginning of the mRNA (29). At the 3′ end, we fused a spacer region of 57–116 amino acids to the reading frame of the scFv to tether the emerging folded polypeptide to the putative polypeptide channel of the ribosome and to give it enough distance to not interfere with folding. This spacer encodes at the RNA level a 3′ stem–loop, either the terminator of the E. coli lipoprotein (29) (lpp term) or the early terminator of phage T3 (30) (T3Te), to increase the stability of mRNA against exonucleases. The mRNA is therefore protected against exonucleases at both ends, much like a natural mRNA would be, but does not contain a translational stop codon. In a direct comparison of flanking regions (Fig. 2B) after one round of translation and selection, we obtained the best result for constructs possessing a 5′-loop (from T7-g10), a 3′-loop (from lpp term), and the longest spacer, 116 amino acids. The yield of mRNA after one round of ribosome display improved from less than 0.001% of input mRNA to 0.015% (15 times).

Figure 2.

(A) Schematic drawing of the scFv construct used for ribosome display. T7 denotes the T7 promoter, SD the ribosome-binding site, F the 3-amino-acid-long FLAG (28) with N-terminal methionine, VL and VH the variable domains of the scFv fragment, L the linker, spacer the part of protein construct connecting the folded scFv to the ribosome, and 5′sl and 3′sl the stem–loops on the 5′ and 3′ ends of the mRNA. The arrow indicates the transcriptional start. The strategy for the PCR amplification is shown. (B) The amount of the scFvhag mRNA bound to the polysome complexes is influenced by the secondary structure of its ends and the length of the spacer connecting the folded scFv to the ribosome. Different constructs of scFvhag mRNA were used for one cycle of ribosome display (constructs c1–c9). None of them contained a stop codon. Each species was tested separately. After affinity selection of the ribosome complexes from 100 μl of translation mixtures, mRNAs were isolated and analyzed by Northern hybridization. The presence of the 5′ stem–loop is labeled + or −; that of the 3′ stem–loop is labeled as − when absent, l when derived from lpp term, or t when derived from T3Te. The spacer length indicates the number of amino acids following the scFv and connecting it to the ribosome, including the translated stem–loop. The lengths of RNA in kb are derived from RNA molecular weight marker III (Boehringer Mannheim). The bar graph shows the quantified amounts of mRNA from fluoroimager analysis. (C) Effect of additives on the amount of mRNA bound to the ribosome complexes. The mRNA of the scFvhag construct c7 was used for one cycle of ribosome display. Samples in B lane c7 and C lane 6 are identical. When indicated, 3.5 mM anti-ssrA oligonucleotide ON10 (5′-TTAAGCTGCTAAAGCGTAGTTTTCGTCGTTTGCGACTA-3′), 35 mg/ml protein disulfide isomerase (PDI), or 1 mg/ml VRC was included in the translation mixture. Translations were stopped by addition of Mg(OAc)2 to the final concentration indicated (in mM) and by cooling on ice. After affinity selection of the ribosome complexes from 100 μl of translation mixtures, mRNAs were isolated and analyzed by Northern hybridization. The bar graph shows the quantified amounts of mRNA from fluoroimager analysis.

Effect of Translation Conditions on Yield.

We then tested the effect of various compounds present during translation. Nucleases were found to be efficiently inhibited by VRC, which should act as transition state analogs (31). VRC at 1 mg/ml maximized the yield of isolated mRNA from ribosome complexes after one round of affinity selection when they were present during translation (Fig. 2C), even though protein synthesis was partially inhibited (data not shown), and omitting VRC led to a severalfold-decreased efficiency of the ribosome display (Fig. 2C). In contrast, Rnasin (10) had no effect on the efficiency of the system (data not shown). We did not find evidence for significant proteolytic degradation of the scFv synthesized under these conditions, since prolonged incubation of released product (up to 300 min) did not alter the electrophoretic pattern (data not shown).

From a systematic study on the in vitro translation of soluble scFv fragments in the presence of molecular chaperones and disulfide-forming catalysts (22), we found that binding activity is obtained if and only if disulfide formation and rearrangement are allowed to take place during translation and folding. The strong beneficial effect of PDI was verified for the ribosome display system, in which the protein is not released. It can be seen that PDI improves the performance of the ribosome display for scFv fragments 3-fold (Fig. 2C) and thus catalyzes the formation and isomerization of disulfide bonds on the ribosome-bound protein.

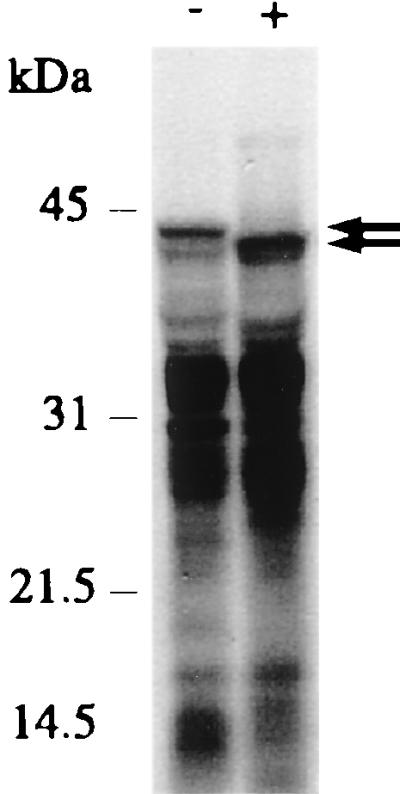

Recently, a peptide tagging system was discovered in E. coli, whereby proteins translated from mRNA, devoid of a stop codon, are modified and released from the ribosomes by the addition of a C-terminal tag, encoded by ssrA RNA, and thereby marked for degradation (32). We thus investigated the inhibition of the action of this RNA by an antisense oligonucleotide complementary to the tag-coding sequence of ssrA RNA. Indeed, a 4-fold higher efficiency of ribosome display is visible in the presence of anti-ssrA oligonucleotide (Fig. 2C), and the molecular weight of the longest protein product is decreased, presumably by preventing the attachment of the degradation tag (Fig. 3). Combining PDI and the anti-ssrA oligonucleotide led to a 12-fold-increased efficiency of the ribosome display system (Fig. 2C).

Figure 3.

Anti-ssrA antisense oligonucleotide ON10 (Fig. 2C) decreases the molecular mass of the longest protein species (arrows). In vitro translation was performed using [35S]methionine and scFvhag c7 mRNA. Reactions were carried out in the absence (−) or presence (+) of 3.5 mM oligonucleotide ON10. An SDS/PAGE of translation products is shown.

By the combination of proper mRNA secondary structure and various compounds present during translation we could increase the yield of mRNA after one round of affinity selection 200 times—from less than 0.001% to 0.2% of input mRNA. This number expresses the combined efficiency of covalent attachment to the ribosome, protein folding, ligand binding, ribosome capture, and RNA release and amplification.

Specific Enrichment of Target mRNA Through Multiple Rounds of Selection.

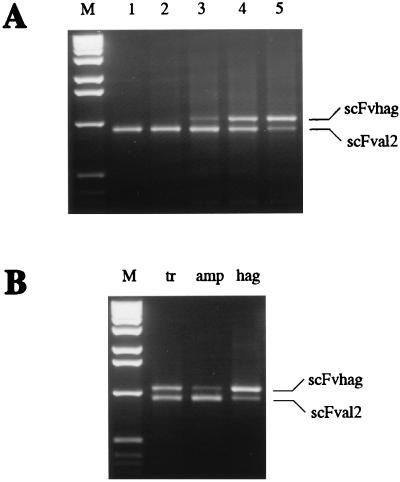

In a test of the optimized system, we investigated how well a mixture of two proteins can be enriched for function. Two scFv antibody mRNAs, constructed identically according to Fig. 2A, both possessing the 5′ and the 3′ T3Te loop, one encoding the anti-hemagglutinin scFv 17/9 (11) (scFvhag), the other the anti-β-lactam antibody AL2 (13) (scFvAL2), were mixed at a ratio of 1:108. Their PCR products differ slightly in length, because of differences mainly in the spacer length, and can thus easily be distinguished (Fig. 4A). After five cycles according to Fig. 1, undergoing selection on immobilized hemagglutinin-peptide, 90% of the ribosome complexes contained scFvhag. We can thus conclude that the enrichment is about 2 orders of magnitude per cycle under these conditions.

Figure 4.

(A) Enrichment of the scFvhag ribosome complexes from mixtures with scFvAL2 by ribosome display. mRNA of scFvhag c5 was diluted 108 times with mRNA of scFvAL2, and the mixture was used for ribosome display. After affinity selection of scFvhag ribosome complexes, mRNA was isolated and reverse transcribed to cDNA using oligonucleotide ON5, and cDNA was amplified by PCR using oligonucleotides ON3 and ON7 and analyzed by agarose electrophoresis. Lanes 1–5 are PCR products amplified after the first to fifth cycles of the ribosome display, respectively. Lane M is the 1-kb DNA ladder (GIBCO/BRL) used as molecular weight markers. PCR products corresponding to scFvhag and scFvAL2 are labeled. (B) Enrichment of either scFvhag c5 or scFvAL2 ribosome complexes by ribosome display as a function of immobilized antigen. mRNAs of scFvhag and scFvAL2 were mixed in a 1:1 ratio and used for one cycle of ribosome display. After affinity selection, mRNA was isolated, reverse transcribed, amplified by PCR, and analyzed by agarose electrophoresis as in A. The same 1:1 mixture was affinity selected on immobilized transferrin (tr) as a control, ampicillin-transferrin conjugate (amp), or hemagglutinin-peptide-transferrin conjugate (hag). PCR products corresponding to scFvhag and scFvAL2 are labeled.

To verify that enrichment really occurred through affinity selection, we tested enrichment of a 1:1 mixture of both mRNAs on an irrelevant surface and saw no change from the input ratio (Fig. 4B). Furthermore, from the identical 1:1 mRNA mixture either antibody could be enriched, depending on which antigen was immobilized (Fig. 4B).

Analysis of scFv Antibody Fragments After Affinity Selection.

After the fifth round of selection, the PCR products were ligated into a vector, which was used to transform E. coli, and single clones were analyzed. Of 20 clones sequenced, 18 had the scFvhag sequence and 2 had the scFvAL2 sequence, demonstrating that the 108-fold enrichment was successful. Of the 18 scFvhag clones, 13 gave ELISA signals within 43–102% of wild type and were inhibitable by soluble hemagglutinin peptide, 2 were reduced to 14% and 18%, and 3 were significantly reduced in binding (less than 10%), probably a result of mistakes from the last PCR amplification (Table 1). Thus, the selective pressure to maintain antigen binding, executed by binding and elution from immobilized antigen, is clearly operating, albeit in the context of an ongoing genetic diversification through PCR errors.

Table 1.

Mutations in scFvhag fragments selected by ribosome display in vitro

| Clone no. | Mutation VL | Mutation VH | Mutation linker | Relative RIA signal | Relative RIA signal +hag | Inhibition, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12 | K45R | P41R | 102 | 6 | 94 | |

| 10 | S30P | 101 | 5 | 95 | ||

| 6* | 100 | 4 | 96 | |||

| 2* | 96 | 5 | 95 | |||

| 7 | G16D | 89 | 5 | 95 | ||

| 3 | Y49H | 86 | 5 | 95 | ||

| 9 | E55G, E105G | A23V | S5P | 86 | 5 | 94 |

| 1 | T20A | G12E | 80 | 3 | 96 | |

| 18 | N(27d)D | D10G, T50N | 76 | 5 | 93 | |

| 4 | V13A, K28R | V12A | 72 | 6 | 91 | |

| 13 | V58I | Y79C | 65 | 8 | 87 | |

| 16 | L83R | I51V, K75E, A113V | 63 | 5 | 92 | |

| 14 | K30E | D61G | S5P | 43 | 6 | 85 |

| 17 | F71S | 18 | 6 | 66 | ||

| 8 | E17G, K18E, K30E | 14 | 6 | 56 | ||

| 5 | L11P | G13D | 9 | 5 | 51 | |

| 11 | S(27e)F, N90S | V48I | 9 | 7 | 22 | |

| 15 | G64D, S77A | G15S | 6 | 6 | 2 |

Mutations in the scFv of the antibody 17/9 (11) are numbered according to Kabat et al. (33) in the variable domains, and sequentially in the linker. Clones are sorted according to a relative RIA signal. Wild-type clones 2 and 6 are marked by asterisks. RIAs were normalized to the same amount of full-length protein and inhibited by 0.1 mM hemagglutinin peptide (denoted as +hag), to verify binding specificity.

The sequence analysis showed that the clones contained between 3 and 7 base changes, with 90% transitions and 10% transversions, in good agreement with the known error properties of Taq DNA polymerase (34). Each clone has gone through a total of 165 cycles of PCR, interrupted by five phenotypic selections for binding, and an error rate of 3.3 × 10−5 can be calculated under these conditions, where only mutations that have survived the selection are counted.

At the protein level, the selected clones carry between 0 and 4 exchanged amino acids, distributed over VL, VH, and the linker. All mutations are independent of each other (Table 1) and give, therefore, an indication of a large range of neutral mutations compatible with function, and perhaps even of improvements the system has selected for. While the exact properties of the selected molecules require further analysis, we note the selection of a proline at the beginning of the linker, which may facilitate the required turn formation (35), and the selection of acidic residues, which are known to increase solubility (36, 37).

Conclusions.

We have shown in this study that it is possible to carry out phenotypic selection for ligand binding with a complete, native protein molecule in vitro by using ribosome display, in this example with a disulfide containing single-chain fragment of an antibody. Functional disulfide-containing protein can be made in vitro, when oxidative folding is suitably catalyzed (22). Since binding of the cognate ligand (antigen) is dependent on the correct three-dimensional structure of the protein (antibody) and its sufficient stability, many molecular properties of a protein can now be selected for. The method described here, ribosome display, does not use any cells at any step, and thus, to our knowledge, constitutes the first evolution and selection system for folded proteins that takes place completely in vitro. No transformation is necessary, and very large libraries become accessible in a single step. While large repertoires have been created for phage display as well (38), many repeated electroporations are necessary, since transformation cannot be scaled up. Furthermore, complex libraries must often be created by repeating this process for the subsequent ligation of different fragments (38). In ribosome display, all replication and amplification, as well as the introduction of the promoter and the 3′ tether, are carried out by PCR in vitro, and thus this method is conveniently interfaced with novel, elegant methods for obtaining even more genetic diversity, such as sexual PCR (39), error-prone PCR (40), or PCR using oligonucleotides made with mixtures of trinucleotide codons (41). Thus, ribosome display is an ideal method for the evolution of proteins through many generations, avoiding the tedious alternation between in vitro and in vivo steps, which would be required to achieve the same with phage display. Conversely, the error rate can also be decreased in ribosome display by the use of proof-reading polymerases, if ribosome display is used merely as a screening tool. We believe that with this technology described here very fundamental questions of protein structure and evolution become accessible for study, and that it has great utility in lead compound identification and optimization.

Acknowledgments

We thank L. Jermutus for many helpful discussions and suggestions in the development of the method, L. Ryabova for helpful discussions on in vitro translation, D. Desplancq for the scFv 17/9, and A. Krebber for the scFvAL2. This work was supported by Schweizerischer Nationalfonds Grant 3100-037717.93/1.

ABBREVIATIONS

- scFv

single-chain fragment of an antibody

- VL

variable domain of light chain

- VH

variable domain of heavy chain

- scFvhag

anti-hemagglutinin scFv 17/9

- scFvAL2

anti-β-lactam antibody AL2

- T3Te

early terminator of phage T3

- lpp term

terminator of E. coli lipoprotein

- PDI

protein disulfide isomerase

- VRC

vanadyl ribonucleoside complexes

References

- 1.Saffhill R, Schneider-Bernloehr H, Orgel L E, Spiegelman S. J Mol Biol. 1970;51:531–539. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(70)90006-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gold L, Polisky B, Uhlenbeck O, Yarus M. Annu Rev Biochem. 1995;64:763–797. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.64.070195.003555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Irvine D, Tuerk C, Gold L. J Mol Biol. 1991;222:739–761. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(91)90509-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Phizicky E M, Fields S. Microbiol Rev. 1995;59:94–123. doi: 10.1128/mr.59.1.94-123.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dower W J, Cwirla S E. In: Guide to Electroporation and Electrofusion. Chang D C, Chassy B M, Saunders J A, Sowers A E, editors. San Diego: Academic; 1992. pp. 291–301. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang W P, Green K, Pinz-Sweeney S, Briones A T, Burton D R, Barbas C F., 3rd J Mol Biol. 1995;254:392–403. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1995.0626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schechter I. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1973;70:2256–2260. doi: 10.1073/pnas.70.8.2256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Payvar F, Schimke R T. Eur J Biochem. 1979;101:271–282. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1979.tb04240.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kraus J P, Rosenberg L E. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1982;79:4015–4019. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.13.4015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mattheakis L C, Bhatt R R, Dower W J. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:9022–9026. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.19.9022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schulze-Gahmen U, Rini J M, Wilson I A. J Mol Biol. 1993;234:1098–1118. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Krebber C, Spada S, Desplancq D, Plückthun A. FEBS Lett. 1995;377:227–231. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)01348-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krebber A, Bornhauser S, Burmester J, Honegger A, Willuda J, Bosshard H R, Plückthun A. J Immunol Methods. 1997;201:35–55. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(96)00208-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goda S K, Minton N P. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23:3357–3358. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.16.3357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Church G M, Gilbert W. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81:1991–1995. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.7.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen H Z, Zubay G. Methods Enzymol. 1983;101:674–690. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(83)01047-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ryabova L A, Vinokurov L M, Shekhotsova E A, Alakhov Y B, Spirin A S. Anal Biochem. 1995;226:184–186. doi: 10.1006/abio.1995.1208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Holschuh K, Gassen H G. J Biol Chem. 1982;257:1987–1992. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pokrovskaya I D, Gurevich V V. Anal Biochem. 1994;220:420–423. doi: 10.1006/abio.1994.1360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ge L, Knappik A, Pack P, Freund C, Plückthun A. In: Antibody Engineering. Borrebaeck C A K, editor. New York: Oxford Univ. Press; 1995. pp. 229–266. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huston J S, Levinson D, Mudgett-Hunter M, Tai M S, Novotny J, Margolies M N, Ridge R J, Bruccoleri R E, Haber E, Crea R, Oppermann H. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:5879–5883. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.16.5879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ryabova L, Desplancq D, Spirin A, Plückthun A. Nature Biotechnology. 1997;15:79–84. doi: 10.1038/nbt0197-79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grentzmann G, Brechemier-Baey D, Heurgue-Hamard V, Buckingham R H. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:10595–10600. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.18.10595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tuite M F, Stansfield I. Mol Biol Rep. 1994;19:171–181. doi: 10.1007/BF00986959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tate W P, Brown C M. Biochemistry. 1992;31:2443–2450. doi: 10.1021/bi00124a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Janosi L, Shimizu I, Kaji A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:4249–4253. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.10.4249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moazed D, Noller H F. Nature (London) 1987;327:389–394. doi: 10.1038/327389a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Knappik A, Plückthun A. BioTechniques. 1994;17:754–761. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Studier F W, Rosenberg A H, Dunn J J, Dubendorff J W. Methods Enzymol. 1990;185:60–89. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(90)85008-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reynolds R, Bermudez-Cruz R M, Chamberlin M J. J Mol Biol. 1992;224:31–51. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(92)90574-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Berger S L. Methods Enzymol. 1987;152:227–234. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(87)52024-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Keiler K C, Waller P R, Sauer R T. Science. 1996;271:990–993. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5251.990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kabat E A, Wu T T, Perry H M, Gottesmann K S, Foeller C. Sequences of Proteins of Immunological Interest. 5th Ed. I. U.S. Dept. Health Human Services; 1991. p. 151. and 464. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Keohavong P, Thilly W G. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:9253–9257. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.23.9253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tang Y, Jiang N, Parakh C, Hilvert D. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:15682–15686. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.26.15682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dale G E, Broger C, Langen H, D’Arcy A, Stüber D. Protein Eng. 1994;7:933–939. doi: 10.1093/protein/7.7.933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Knappik A, Plückthun A. Protein Eng. 1995;8:81–89. doi: 10.1093/protein/8.1.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vaughan T J, Williams A J, Pritchard K, Osbourn J K, Pope A R, Earnshow J C, McCafferty J, Hodits R A, Wilton J, Johnson K S. Nat Biotechnol. 1996;14:309–314. doi: 10.1038/nbt0396-309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stemmer P. Nature (London) 1994;370:389–391. doi: 10.1038/370389a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cadwell R C, Joyce G F. PCR Methods Appl. 1994;3:S136–S140. doi: 10.1101/gr.3.6.s136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Virnekäs B, Ge L, Plückthun A, Schneider K C, Wellnhofer G, Moroney S E. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:5600–5607. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.25.5600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]