Abstract

Reaction-intermediate analogs have been used to understand how phosphoryl-transfer enzymes promote catalysis. Herein we report the first structure of a small ribozyme crystallized with a 3′-OH, 2′,5′-linkage in lieu of the normal phosphodiester substrate. The new structure shares features of the reaction coordinate exhibited in prior ribozyme structures including a vanadate complex that mimicked the oxyphosphorane transition state. As such, the structure exhibits reaction-intermediate traits that allow direct comparison of stabilizing interactions to the 3′-OH, 2′,5′-linkage contributed by the RNA enzyme and its protein counterpart, ribonuclease. Clear similarities are observed between the respective structures including hydrogen bonds to the non-bridging oxygens of the scissile-phosphate. Other commonalities include carefully poised water molecules that may alleviate charge build-up in the transition state and placement of a positive charge near the leaving group. The advantages of 2′,5′-linkages to investigate phosphoryl-transfer reactions are discussed, and argue for their expanded use in structural studies.

Keywords: Phosphoryl-transfer; reaction-intermediate; transition-state stabilization; ribonuclease; hairpin ribozyme; 2′,5′-phosphodiester

Introduction

Phosphoryl transfer reactions pervade biological systems and are critical for RNA transcription, maturation and turnover [1, 2]. Understanding the mechanism of action of such processes requires capturing enzyme structures representative of reaction intermediates, which allows identification of key functional groups that stabilize the transition state [3]. Vanadium-oxide, AlF4− and MgF3− have enjoyed wide use as transition-state mimics in protein crystallography [4–6]. However, these metallo-complexes can be unwieldy since they demonstrate pH sensitivity [7, 8], limited solubility [4, 8], and may result in partial atomic occupancy (PDB codes 2P7E [9], 1RUV [10] and 1M7G [11]). The relevance of vanadium-oxide binding in the ribonuclease (RNase) A active site [10, 12] has been challenged, since amino acids poised for transition-state stabilization did not support roles ascribed by biochemical and kinetic analyses [13]. Complementary studies of RNases have been conducted in the presence of substrate analogs comprising 3′-OH, 2′,5′-linkages at the site of cleavage [14–16]. Several such structures were consistent with expectations for transition-state stabilization including placement of positively charge functionalities near the leaving group, and hydrogen-bond donors at the non-bridging oxygens of the scissile bond.

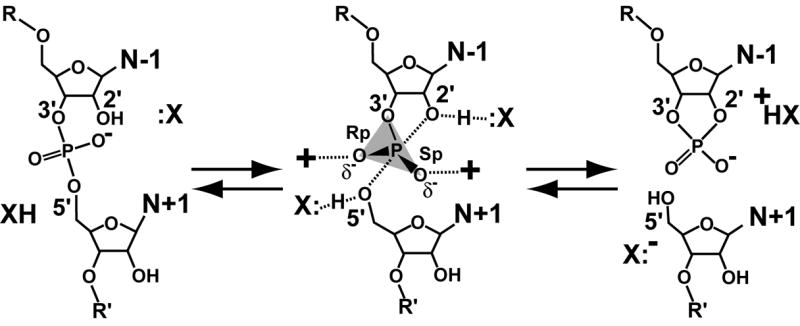

The hairpin ribozyme is a small, naturally occurring RNA enzyme that catalyzes phosphodiester cleavage comparable to the first reaction conducted by a handful of protein ribonucleases (Fig. 1) [17–19]. Prior crystallographic analyses of the hairpin ribozyme benefited from use of vanadium-oxide, as well as a 3′-deoxy, 2′,5′-linkage at the scissile bond, which provided some insight into transition-state stabilization [9, 20, 21]. However, known discrepancies in the RNase-vanadate structure and absence of a 3′-OH group in prior 2′,5′-hairpin ribozyme variants led to a more circumspect approach when making a direct comparison of the ribozyme’s active site to that of RNase. Although it is generally accepted that the principles of RNA catalysts are comparable to those of proteins [22], no direct structural comparison between functionally-related RNA and protein enzymes has been made using the same inhibitor to induce catalytically relevant conformations.

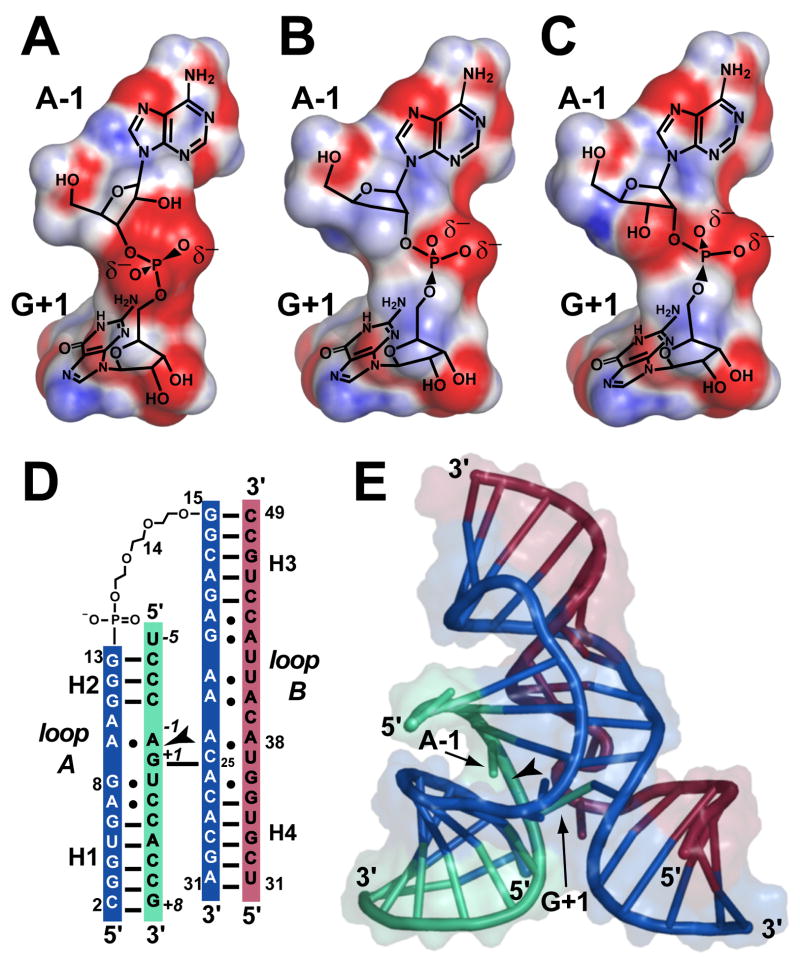

Figure 1.

The chemical reaction of small ribozymes. X: represents a group that activates the 2′-nucleophile; XH serves as a proton source for the 5′-leaving group. The transition state is characterized by a pentacoordinate phosphorus and is associated with excess electron density on the non-bridging oxygens. The products are a cyclic, 2′,3′-phosphodiester and a 5′-OH.

The goal of this investigation was to make such a comparison by determining the hairpin ribozyme structure in complex with a substrate analog harboring a 3′-OH, 2′,5′-linkage. In the course of the analysis, the pros and cons of using a 3′-OH 2′,5′-linked analog versus a 3′-deoxy variant are considered. Importantly, the results indicate remarkable similarities between the putative modes of transition-state stabilization used by these two evolutionarily disparate enzyme classes. This comparison affords an opportunity to consider the mechanistic strategies of small RNA enzymes from a previously unavailable vantage point.

Materials and methods

Phosphoramidite synthesis

A commercially available phosphoramidite does not exist for the 3′-OH, 2′,5′-phosphodiester linkage. To obtain this product in the context of the hairpin ribozyme 13-mer substrate, it was necessary to produce a modified adenosine phosphoramidite for solid phase coupling [23]. The inactivated starting material, 2′-OH-3′-t-butyldimethylsilyl-5′-O-DMT N6-benzoyl adenosine, was obtained from Chemgenes Corp. (Wilmington, MA). Fifty mg (0.062 mmol) were added at 25 °C to N,N-diisopropylethylamine (32 μl, 0.187 mmol) and 2-cyanoethyl N,N-diisopropylchloro-phosphoramidite (27 μl, 0.124 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (1.5 ml). This mixture was stirred 90 min in CHCl3 (10 ml), followed by washing with aqueous NaHCO3, H2O, brine and dried (Na2SO4). Concentration was in vacuo. Purification was by silica gel column chromatography using neutral gel, 2.5 × 15 cm, in a solvent of 50% (v/v) ethyl acetate in hexane. The product was 2′-O-(2-cyanoethyl-N,N-diisopropylphosphoramidite)-3′-t-BDMSi-5′-O-DMT N6-benzoyl adenosine (50.3 mg, 82%), which appeared as white foam. The product was confirmed by 31P NMR in CDCl3 (400 MHz) with peak chemical shifts (δ) at 147.26 ppm and 146.92 ppm. APCI mass spectrometry identified a peak at 988.19 amu relative to the calculated mass of 987.45 for C53H66N7O8PSi (MH+).

Crystallization

The hairpin ribozyme construct employed in this investigation has been described [9, 24]. The two longest strands and the bona fide substrate (Fig. 2D) were synthesized by Dharmacon (Fayette, CO). The 29-mer contains a 10-atom linker in place of the natural adenosine to tether the loop A and B domains [24]. The 3′-OH, 2′,5′-linked 13-mer was synthesized by Fidelity Systems (Gaithersburg, MD) using the custom phosphoramidite at A-1. The 3′-deoxy, 2′,5′-linked 13-mer was prepared as described [9]. All strands were deprotected in-house, HPLC purified and desalted prior to use [25, 26].

Figure 2.

Active site phosphodiester bond configurations and schematic diagrams of the hairpin ribozyme. (A-C) Dinucleotide electrostatic surfaces for the scissile bond in the charge range −10 (red) to +10 (blue) kTe−1, where k is the Boltzmann constant, T is the absolute temperature and e is the unit charge. Coordinates in (A) were derived from the 3′,5′-linkage of the wild-type substrate [31], (B) a 3′-deoxy, 2′,5′-phosphodiester substitution [9], and (C) the 3′-OH, 2′,5′-linkage derived herein. (D) Diagram of the minimal hairpin ribozyme construct used in this and prior investigations [9, 24]. The substrate strand is green with the cleavage site indicated by an arrowhead. The ‘ribozyme’ strands are red and blue. Black horizontal lines indicate canonical hydrogen bonds; non-canonical interactions are shown as dots. Helical regions are labeled H1–H4. (E) Cartoon of the global hairpin ribozyme fold. Hydrogen bonds between bases are indicated by connected tubes. The molecular surface is rendered translucently. Figs 2A–C and 2E were created by PyMOL [30].

Crystallization, X-ray diffraction and data collection

The hairpin ribozyme strands were docked according to published methods [24, 25]. Crystals grew by vapor-diffusion at 20 °C from 20.5 % (w/v) PEG 2K MME, 0.10 M Na Cacodylate pH 6.5, 0.25 M Li2SO4, 2.5 mM Co(NH3)6Cl3 and 2 mM spermidine-HCl. Hexagonal rods reached a maximum size of 0.2 mm × 0.075 mm × 0.075 mm in 2 weeks; cryoprotection was described previously [9]. A single crystal was frozen in a stream of nitrogen gas (X-Stream, Rigaku-MSC) prior to data collection on a Rigaku RUH2R rotating-anode generator. Diffraction images were recorded on an R-Axis IV image-plate system with confocal optics (Rigaku). A total of 120 images were collected at a crystal-to-detector distance of 15.0 cm with 20 min exposures and 0.5° oscillation per frame.

Data Processing, Structure Determination and Refinement

X-ray diffraction data were processed with CrystalClear (Rigaku-MSC). Data reduction statistics are in Table 1. The structure was solved by difference Fourier methods using the previous 3′-deoxy, 2′,5′-linked structure (PDB code 2P7F) as a starting model. To avoid statistical bias, the excluded Rfree reflections were matched to the previous data set. Additional test set reflections were chosen at random until a total of 7.4% of the data were excluded. Refinement methods have been described [9, 24]. Average RMS deviations were calculated using the CCP4 suite [27].

Table 1.

X-ray diffraction and refinement statistics

| PDB accession code | 3CQS |

|---|---|

| Space group | P6122 |

| Unit cell (Å) | a = 93.16, c = 129.05 |

| Resolution (Å)a | 34.20 – 2.80 (2.90 – 2.80) |

| Mosaicity (deg) | 1.82 |

| Total number of reflections | 43050 |

| Number of unique reflections | 8458 |

| Redundancya | 5.09 (4.80) |

| Completeness (%)a | 98.0 (99.4) |

| <I/σ(I)>a | 15.5 (2.8) |

| Rsym (%)a,b | 0.056 (0.445) |

| Number of RNA atomsc | 1314 |

| Number of waters | 6 |

| Number of ions | 1 Co(NH3)6(III) |

| Average B for RNA/water (Å2) | 82.2/62.7 |

| Rcryst/Rfree (%)d,e | 22.0/25.4 |

| RMSD for bonds (Å) | 0.009 |

| RMSD for angles (deg) | 1.50 |

| Coordinate error (Å)f | 0.52 |

Values referring to the highest resolution shell are in parentheses.

Rsym = Σhkl|Ij −<Ij>|/Σhkl|Ij| × 100.

Number of RNA atoms includes dual conformations for U-5, but not the 13 atoms of the S9 linker.

Rcryst = Σhkl|Fo − kFc|/Σhkl|Fo| × 100, where k is a scale factor.

Rfree is defined as the Rcryst calculated using 7.4% of the data selected as described in Methods and excluded from refinement.

Based upon the cross-validated Luzzati plots calculated in CNS for the full resolution range.

Electrostatics

Hydrogen atoms and charges for each dinucleotide were assigned by the PDB2PQR server using the AMBER forcefield [28]. Electrostatic surface potentials were obtained by numerical solution of the Poisson-Boltzmann equation implemented in APBS [29] using default values. The potential maps (Figs. 2A–C) were displayed in PyMOL [30].

Activity Assay

Single-turnover assays for each linkage configuration at the cleavage site (Figs. 2A–C) were performed as described [24]. Each data point is the average of two independent measurements that were within 10% of each other.

Results & Discussion

Global Fold and Quality of the 3′-OH, 2′,5′-Phosphodiester Complex

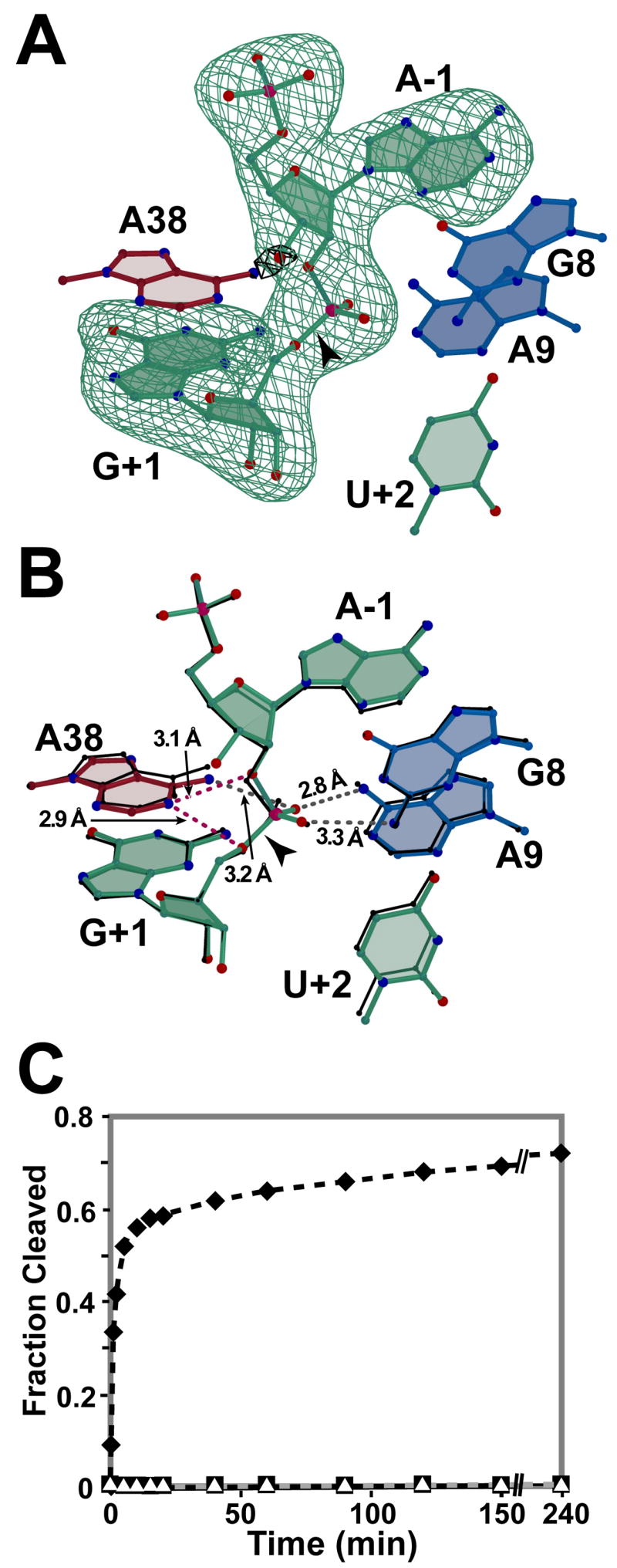

The structure of a hinged hairpin ribozyme incorporating a 3′-OH, 2′,5′-phosphodiester linkage at the site of substrate cleavage (3′-OH, 2′,5′; Fig. 2C) was solved and refined to 2.8 Å resolution as a basis for comparison with previous hairpin ribozyme structures, as well as their protein counterparts. The global fold (Fig. 2E) closely resembled previously reported hairpin ribozyme crystal structures. Refinement of the 3′-OH, 2′,5′ structure converged with reasonable statistics (Table 1) including modest RMS deviations from ideal bond lengths and angles, as well as Rcryst and Rfree values of 22.0 % and 25.4 %, respectively. The quality of the refined model is indicated further by its fit to reduced-bias, simulated-annealing omit electron density maps that exhibited well-defined features for the 3′-OH, 2′,5′-linkage and the neighboring A-1 and G+1 residues (Fig. 3A). A similar analysis revealed strong electron density for the 3′-hydroxyl group at A-1, which guided efforts to fit the new model. An all-atom superposition with the starting model (Fig. 3B) containing a comparable 3′-deoxy, 2′,5′-phosphodiester substrate linkage (2′,5′; Fig. 2B [9]) produced an RMSD of 0.31 Å.

Figure 3.

Active site views and catalytic activity. (A) Simulated annealing omit electron density maps resulting from exclusion of nucleotides A-1 and G+1 (green, 3σ) or the 3′-oxygen of A-1 (black, 5 σ from the phase calculation. Nearby nucleobases are depicted for perspective. Carbon atoms are colored as in Fig. 2D. Oxygen, nitrogen and phosphorus atoms are colored red, blue and pink, respectively. (B) The 3′-OH, 2′,5′ structure of this study superimposed on the 3′-deoxy, 2′,5′ structure (black lines; [9]). Putative hydrogen bonds are depicted as broken gray lines with distances labeled. Perceived weak hydrogen bonds are broken red lines. (C) Cleavage activity of crystallization constructs on substrate and analogs with linkages in Fig. 2A–C: wild type 3′,5′ (filled diamond); 3′-deoxy, 2′,5′ and 3′-OH, 2′,5′ (filled square and open triangle, respectively). Figs. 3A–B & 4 were created by Bobscript [38].

Activity Assays

In general, low levels of substrate cleavage by the hairpin ribozyme cannot be detected crystallographically, which necessitates the use of more sensitive methods [31]. The hepatitis δ virus ribozyme (HDV) and the hairpin ribozyme have each been tested for cleavage activity on a 3′-OH, 2′,5′-phosphodiester linkage. The HDV was active [32] making it ill-suited as a reaction-intermediate analog. In contrast, a 3′-OH, 2′,5′-phosphodiester substrate analog was a competitive inhibitor of a longer, naturally-occurring hairpin ribozyme sequence [33]. As a quality control measure for the hairpin ribozyme crystallization construct employed herein, its cleavage activity was measured in single-turnover assays (Fig. 3C). The activity measured for the wild-type 3′,5′-phosphodiester linkage (Fig. 2A) showed fast and slow rate constants of 0.8 min−1 and 0.01 min−1 in solution, comparable to prior work [24]. The 3′-deoxy, 2′,5′-phosphodiester (Fig. 2B) served as a negative control due the absence of a nucleophile. Importantly, no cleavage was detected for the substrate analog containing the 3′-OH, 2′, 5′-phosphodiester (Fig. 2C), thus corroborating the prior report measured under initial velocity conditions [33], as well as the crystallographic observations herein (Fig. 3A).

Differences and Similarities between 3′-OH, 2′,5′ and 3′-Deoxy, 2′,5′ Analog Structures

Due to the distinctive electrostatic charge properties and hydrogen bonding capabilities of the different 2′,5′-linkages (Fig. 2B versus 2C), the 3′-OH, 2′,5′ hairpin ribozyme structure was solved as a basis for comparison with the 3′-OH, 2′,5′-UpA analog employed for RNase [15]. The modest RMSD between the new 3′-OH, 2′-5′ variant versus a prior 3′-deoxy 2′,5′ construct (Fig. 3B) was consistent with the absence of new hydrogen bond interactions to the 3′-OH of A-1. This outcome was anticipated [9], but required experimental confirmation since the equivalent 3′-moiety of RNase exhibited van der Waals, ionic, backbone and/or solvent contacts [14, 15, 34]. Despite the absence of 3′-OH interactions, subtle differences were observed between the 3′-OH, 2′,5′ and former 3′-deoxy, 2′,5′ structures. For example, the prior structure exhibited a hydrogen bond between the A38 N6 amine and the pro-R oxygen (equivalent) of the scissile phosphate. This interaction was ~0.4 Å longer in the 3′-OH, 2′,5′ structure, and exhibited an 81° angle compared to the expected, nearly-tetrahedral (111°) angle observed previously. Significantly, this contact point may contribute to an elevated pKa at the N1 imino position of A38 via an inductive effect. Thus, interactions or geometries that disrupt the ‘fitness’ of this interaction could contribute to weakening of other stabilizing active-site interactions that depend on protonation of the A38 N1 position. To illustrate, the prior 3′-deoxy, 2′,5′ structure exhibited a bifurcated hydrogen bond between the A38 imino (apparent H-bond donor) to both the 5′-oxygen of G+1 (the leaving group of cleavage) and the 2′-oxygen of A-1 [9]. In the 3′-OH, 2′,5′ structure, these interactions (Fig. 3B, red bonds) demonstrated less optimal interaction geometry (i.e. the angle between the G+1 C5′-O5′ bond and N1 of A38 is 76°, compared to the expected ~109° (tetrahedral) or 85° angle observed for the 3′-deoxy, 2′,5′ structure).

The inability of an analog to elicit optimal active site stabilization may be manifested in other ways. Crystals of the 3′-OH, 2′,5′-linked hairpin ribozyme do not reach the size or quality (Table 1) of those prepared in the absence of the 3′-OH, which diffracted to 2.35 Å and displayed a ~1.2° lower mosaic spread [9]. Therefore, while minute changes in bond lengths and angles are difficult to accurately measure at 2.8 Å resolution, the evidence collectively suggests that the 3′-OH at A-1 notably perturbs formation of optimal interaction networks that stabilize a reaction-intermediate-like conformation. These results imply that the choice of analogs may be empirical for any given enzyme. In this investigation, preference of the 3′-OH, 2′-5′ linkage seemed necessary to directly compare a ribozyme active site to that of a protein.

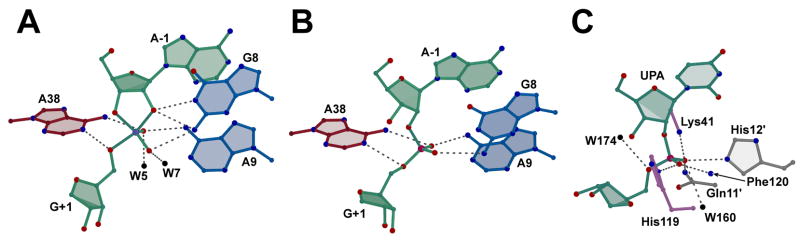

The 3′-OH, 2′,5′-Linkage Exhibits Features of the Hairpin Ribozyme Reaction Coordinate

The 3′-OH, 2′,5′ structure revealed an active site arrangement similar to that of three previously determined hairpin ribozyme crystal structures prepared in the presence of reaction-intermediate or transition-state mimics (Fig. 3B; Figs. 4A versus 4B). Each structure appeared to employ an induced-fit conformational change relative to ‘pre-catalytic’ structures, which was achieved through stabilization of the scissile bond [9, 20]. In particular, the scissile phosphate non-bridging oxygens adopted a comparable orientation in these complexes that has been discussed widely in terms of geometric and electrostatic stabilization [9, 20, 35]. Amidine nucleobase interactions contributed by A38, G8 and A9 support this conformation in the current and past structures (Figs. 3B, 4A, 4B) [9]. Evidence that water molecules contribute geometric and electrostatic stabilization to the scissile phosphate non-bridging oxygens also exists from the vanadium-oxide and 3′-deoxy, 2′,5′ hairpin ribozyme structures [9]. Additional reinforcing interactions have been observed between A38 imino and the 5′-leaving-group of G+1 [9, 20], and are consistent with biochemical investigations supporting this interaction [35–37]. It is noteworthy that such interactions persist despite differences in analog geometry (i.e. tetrahedral phosphate vs. trigonal-bipyramidal vanadate) and manage to preserve the non-bridging oxygen and 5′-leaving group orientations. This observation suggests that active site interactions with the various substrate analogs are highly favorable and persist despite markedly different linkages. Overall, the preservation of interactions that robustly stabilize the scissile phosphate supports the classification of the 3′-OH, 2′,5′-phosphodiester as a reaction-intermediate mimic.

Figure 4.

Active site comparisons of 3′-OH, 2′,5′ analogs. (A) The hinged hairpin ribozyme solved with vanadate in lieu of the scissile phosphate [9]. Putative stabilizing interactions are depicted as in Fig. 3B. Active site waters, if present, are indicated by black spheres in all panels. The vanadium atom is light blue. (B) The 3′-OH, 2′,5′-linkage of this investigation. (C) Active site view of BS-RNase [15] including catalytic residues His12, His119 and Lys41. Hydrogen bonds reported as stabilizing the scissile phosphate [15] are depicted as broken grey lines. For clarity, only the terminal atoms of the Lys41 and Glu11 are shown. The backbone amide nitrogen of Phe120 is depicted as a blue sphere. Prime (′) is used to denote symmetry related residues within the biological dimer.

Comparison of RNA and protein enzyme structures containing the 3′-OH, 2′,5′-analog

The 3′-OH, 2′,5′ structure represents a unique opportunity to compare structures of RNA and protein enzymes that catalyze an equivalent chemical reaction and were crystallized with the same reaction-intermediate analog. The number and types of stabilizing interactions present in both active sites are remarkably similar considering that the cleavage activities of these enzymes evolved independently. The orientation of the scissile phosphate non-bridging oxygens relative to the adjacent 5′ ribose is strikingly similar in both the hairpin ribozyme and bovine seminal (BS) RNase [34] structures containing a 3′-OH, 2′,5′-linked substrate analog (Fig. 4B versus 4C). This orientation is stabilized extensively in the BS-RNase active site by five functional groups contributed by side-chains and the peptide backbone. Significantly, a water molecule coordinates to the pro-R oxygen (equivalent) in a manner reminiscent of the geometric and electrostatic stabilization role proposed for wat5 in the previous 3′-deoxy, 2′,5′ structure [9, 15]. Stabilization of the non-bridging oxygens by multiple functional groups appears to provide both a leverage point to distort the scissile phosphorus into the phosphorane geometry and ameliorate the unfavorable negative charge localization that accumulates during the reaction [13]. Significantly, placement of a positively charged imidazole (His119) near the 5′-leaving group of RNase is analogous to the localization of the A38 ring, which is hypothesized to carry a positive charge due to an inductive pKa effect [21]. Although this comparison cannot resolve the subtleties of various catalytic proposals, the results help frame the problem by reinforcing chemical similarities.

Implications for other enzymes

Trapping enzymes in conformations representative of reaction-intermediate states helps advance knowledge of structure-function relationships [3]. Analogs comprising a 2′,5′-phosphodiester bond represent valuable resources in the crystallographer’s ‘toolkit’. Application of this analog to the hairpin ribozyme circumvented problems associated with the use of metallo-complexes and the 3′-OH, 2′,5′ structure herein has helped highlighted parallels between protein and RNA enzymes that are functionally-related, yet chemically divergent. In the end, the investigator’s choice of a 3′-deoxy versus a 3′-OH, 2′,5′-analog should be influenced by differences in the steric and electrostatic properties of each, as well as the additional chemical synthetic steps necessary to produce the latter linkage. The results of this investigation suggest that 2′,5′-phosphodiester analogs should be considered an alternative choice for the investigation of phosphoryl transfer enzyme structures, including small ribozymes prone to product dissociation.

Footnotes

We wish to acknowledge funding from NIH grant GM63162 (JEW) as well as Elon Huntington Hooker and Leon Miller graduate fellowships (ATT).

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Works Cited

- 1.Kornberg RD. The molecular basis of eukaryotic transcription. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:12955–12961. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704138104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Butler JS. The yin and yang of the exosome. Trends Cell Biol. 2002;12:90–96. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(01)02225-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lolis E, Petsko GA. Transition-state analogues in protein crystallography: probes of the structural source of enzyme catalysis. Annu Rev Biochem. 1990;59:597–630. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.59.070190.003121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davies DR, Hol WG. The power of vanadate in crystallographic investigations of phosphoryl transfer enzymes. FEBS Lett. 2004;577:315–321. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wittinghofer A. Signaling mechanistics: aluminum fluoride for molecule of the year. Curr Biol. 1997;7:R682–685. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(06)00355-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Graham DL, Lowe PN, Grime GW, Marsh M, Rittinger K, Smerdon SJ, Gamblin SJ, Eccleston JF. MgF(3)(−) as a transition state analog of phosphoryl transfer. Chem Biol. 2002;9:375–381. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(02)00112-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baxter NJ, Blackburn GM, Marston JP, Hounslow AM, Cliff MJ, Bermel W, Williams NH, Hollfelder F, Wemmer DE, Waltho JP. Anionic Charge Is Prioritized over Geometry in Aluminum and Magnesium Fluoride Transition State Analogs of Phosphoryl Transfer Enzymes. J Am Chem Soc. 2008 doi: 10.1021/ja078000n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crans DC, Smee JJ, Gaidamauskas E, Yang L. The chemistry and biochemistry of vanadium and the biological activities exerted by vanadium compounds. Chem Rev. 2004;104:849–902. doi: 10.1021/cr020607t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Torelli AT, Krucinska J, Wedekind JE. A comparison of vanadate to a 2′-5′ linkage at the active site of a small ribozyme suggests a role for water in transition-state stabilization. RNA. 2007;13:1052–1070. doi: 10.1261/rna.510807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ladner JE, Wladkowski BD, Svensson LA, Sjolin L, Gilliland GL. X-ray Structure of Ribonuclease A-Uridine Vandate Complex at 1.3 Å Resolution. Acta Crystallogr. 1997;D53:290–301. doi: 10.1107/S090744499601582X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lansdon EB, Segel IH, Fisher AJ. Ligand-induced structural changes in adenosine 5′-phosphosulfate kinase from Penicillium chrysogenum. Biochemistry. 2002;41:13672–13680. doi: 10.1021/bi026556b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wlodawer A, Miller M, Sjolin L. Active site of RNase: neutron diffraction study of a complex with uridine vanadate, a transition-state analog. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1983;80:3628–3631. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.12.3628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Raines RT. Ribonuclease A. Chem Rev. 1998;98:1045–1066. doi: 10.1021/cr960427h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koepke J, Maslowska M, Heinemann U, Saenger W. Three-dimensional structure of ribonuclease T1 complexed with guanylyl-2′,5′-guanosine at 1.8 A resolution. J Mol Biol. 1989;206:475–488. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(89)90495-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vitagliano L, Adinolfi S, Riccio A, Sica F, Zagari A, Mazzarella L. Binding of a substrate analog to a domain swapping protein: X-ray structure of the complex of bovine seminal ribonuclease with uridylyl(2′,5′)adenosine. Protein Sci. 1998;7:1691–1699. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560070804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vitagliano L, Merlino A, Zagari A, Mazzarella L. Productive and nonproductive binding to ribonuclease A: X-ray structure of two complexes with uridylyl(2′,5′)guanosine. Protein Sci. 2000;9:1217–1225. doi: 10.1110/ps.9.6.1217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McKay DB, Wedekind JE. Small Ribozymes. The RNA World. 1999:265–286. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bevilacqua PC, Yajima R. Nucleobase catalysis in ribozyme mechanism. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2006;10:455–464. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2006.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Walter NG. Ribozyme catalysis revisited: is water involved? Mol Cell. 2007;28:923–929. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rupert PB, Massey AP, Sigurdsson ST, Ferré-D’Amaré AR. Transition state stabilization by a catalytic RNA. Science. 2002;298:1421–1424. doi: 10.1126/science.1076093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.MacElrevey C, Salter JD, Krucinska J, Wedekind JE. Structural effects of nucleobase variations at key active site residue ade38 in the hairpin ribozyme. RNA. 2008 doi: 10.1261/rna.1055308. Submitted. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Doudna JA, Lorsch JR. Ribozyme catalysis: not different, just worse. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2005;12:395–402. doi: 10.1038/nsmb932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Beigelman L, Karpeisky A, Matulic-Adamic J, Haeberli P, Sweedler D, Usman N. Synthesis of 2′-modified nucleotides and their incorporation into hammerhead ribozymes. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23:4434–4442. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.21.4434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.MacElrevey C, Spitale RC, Krucinska J, Wedekind JE. A posteriori design of crystal contacts to improve the X-ray diffraction properties of a small RNA enzyme. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2007;63:812–825. doi: 10.1107/S090744490702464X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grum-Tokars V, Milovanovic M, Wedekind JE. Crystallization and X-ray diffraction analysis of an all-RNA U39C mutant of the minimal hairpin ribozyme. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2003;59:142–145. doi: 10.1107/s0907444902019066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wedekind JE, McKay DB. Purification, crystallization, and X-ray diffraction analysis of small ribozymes. Methods Enzymol. 2000;317:149–168. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(00)17013-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.CCP4. The CCP4 suite: programs for protein crystallography. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1994;50:760–763. doi: 10.1107/S0907444994003112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dolinsky TJ, Nielsen JE, McCammon JA, Baker NA. PDB2PQR: an automated pipeline for the setup of Poisson-Boltzmann electrostatics calculations. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:W665–667. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Baker NA, Sept D, Joseph S, Holst MJ, McCammon JA. Electrostatics of nanosystems: application to microtubules and the ribosome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:10037–10041. doi: 10.1073/pnas.181342398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.W.L. DeLano. Copyright 2004. The PyMOL molecular graphics system.

- 31.Salter J, Krucinska J, Alam S, Grum-Tokars V, Wedekind JE. Water in the Active Site of an All-RNA Hairpin Ribozyme and Effects of Gua8 Base Variants on the Geometry of Phosphoryl Transfer. Biochemistry. 2006;45:686–700. doi: 10.1021/bi051887k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shih IH, Been MD. Ribozyme cleavage of a 2,5-phosphodiester linkage: mechanism and a restricted divalent metal-ion requirement. Rna. 1999;5:1140–1148. doi: 10.1017/s1355838299990763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Feldstein PA, Buzayan JM, van Tol H, deBear J, Gough GR, Gilham PT, Bruening G. Specific association between an endoribonucleolytic sequence from a satellite RNA and a substrate analogue containing a 2′-5′ phosphodiester. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87:2623–2627. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.7.2623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vitagliano L, Adinolfi S, Sica F, Merlino A, Zagari A, Mazzarella L. A potential allosteric subsite generated by domain swapping in bovine seminal ribonuclease. J Mol Biol. 1999;293:569–577. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kuzmin YI, Da Costa CP, Cottrell JW, Fedor MJ. Role of an active site adenine in hairpin ribozyme catalysis. J Mol Biol. 2005;349:989–1010. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bevilacqua PC. Mechanistic considerations for general acid-base catalysis by RNA: revisiting the mechanism of the hairpin ribozyme. Biochemistry. 2003;42:2259–2265. doi: 10.1021/bi027273m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pinard R, Hampel KJ, Heckman JE, Lambert D, Chan PA, Major F, Burke JM. Functional involvement of G8 in the hairpin ribozyme cleavage mechanism. EMBO J. 2001;20:6434–6442. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.22.6434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Esnouf RM. Further additions to MolScript version 1.4, including reading and contouring of electron-density maps. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1999;55:938–940. doi: 10.1107/s0907444998017363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]