Abstract

During development, descending projections to the spinal cord are immature. Available data suggest that even though these projections are not fully formed, they contribute to activation of spinal circuitry and promote development of network function. Here we examine the modulation of sacrocaudal afferent-evoked locomotor activity by descending pathways. We first examined the effects of brainstem transection on the afferent evoked locomotor-like rhythm using an isolated brainstem–spinal cord preparation of the mouse. Transection increased the frequency and stability of the locomotor-like rhythm while the phase remained unchanged. We then made histologically verified lesions of the ventrolateral funiculus and observed similar effects on the stability and frequency of the locomotor rhythm. We next tested whether these effects were due to downstream effects of the transection. A split-bath was constructed between the brainstem and spinal cord. Neural activity was suppressed in the brainstem compartment using cooled high sucrose solutions. This manipulation led to a reversible change in frequency and stability that mirrored our findings using lesion approaches. Our findings suggest that spontaneous brainstem activity contributes to the ongoing modulation of afferent-evoked locomotor patterns during early postnatal development. Our work suggests that some of the essential circuits necessary to modulate and control locomotion are at least partly functional before the onset of weight-bearing locomotion.

It is well established that networks of neurons located in the spinal cord generate locomotor activity in vertebrates (Graham-Brown, 1911; Grillner, 2003). These networks can produce a phasic coordinated locomotor output in the presence of some form of excitatory input and have been termed central pattern generators (CPGs). Data from several species, including the lamprey, cat and rat, have demonstrated that reticulospinal projections from the pons and medulla play an important role in initiating locomotion (Steeves & Jordan, 1980; Atsuta et al. 1990; El Manira et al. 1997; Noga et al. 1988; Noga et al. 1991; Sirota et al. 2000). Classic studies demonstrated that stimulation of the mesencephalic locomotor region (MLR) could produce coordinated stepping in decerebrate cats (Shik et al. 1969). The MLR in turn projects to the medullary reticular formation (MRF) pathway, which sends projections into the ventrolateral funiculus (VLF) of the spinal cord. Acute lesions or cooling of VLF can block MLR induced locomotor activity (Noga et al. 1991).

The neurotransmitters that are released by descending MRF projections have not been fully established. However, indirect evidence from in vitro studies in rats and the lamprey suggest that glutamate is a likely candidate for boosting the excitability of spinal circuits thereby facilitating the activation of CPGs (Jordan et al. 2008). Other candidates for activating CPGs are the monoamines. These neuromodulators are released within the spinal cord following brainstem stimulation (Gerin et al. 1994; 1995; Jordan & Schmidt, 2002), and bath application of monoamines can activate CPGs in rats (Smith & Feldman, 1987; Cazalets et al. 1992; Cowley & Schmidt, 1994; Whelan et al. 2000) and mice (Jiang et al. 1999; Nishimaru et al. 2000; Whelan et al. 2000; Madriaga et al. 2004). Recently, it was shown that a serotonergic pathway responsible for eliciting locomotion in neonatal rats originates in the parapyramidal region of the medulla (Liu & Jordan, 2005).

While descending bulbospinal projections are known to initiate locomotion, they can also modulate the timing and pattern of locomotion. For example, stimulation of the MLR at different stimulation intensities can increase the amplitude and frequency of the stepping pattern (Shik et al. 1969). The reticulospinal system in intact cats has been found to contribute to the generation of corrective signals that are imposed on the spinal CPG (Drew et al. 2004). Studies using isolated mouse (Whelan et al. 2000; Madriaga et al. 2004; Gordon & Whelan, 2006b) and rat (Cazalets et al. 1992; Cowley & Schmidt, 1994; Beato & Nistri, 1998; Pearlstein et al. 2005) spinal cord preparations show that bath application of monoamines, which are normally released by bulbospinal projections, modulates the timing, amplitude and pattern of CPG activity.

Nevertheless, much remains unknown regarding the effects of bulbospinal modulation of spinal CPGs and this is especially true for the developing rodent. To address this issue we make use of an isolated brainstem–spinal cord preparation where the spinal CPG is activated by stimulation of primary afferents and bulbospinal connections are intact. While stimulation of lumbar dorsal roots can activate spinal CPGs, we and others have found that stimulation of sacrocaudal afferents in the rat (Lev-Tov et al. 2000; Strauss & Lev-Tov, 2003; Blivis et al. 2007) and the mouse (Whelan et al. 2000; Gordon & Whelan, 2006b) effectively evoke bouts of regular locomotor activity. This type of preparation has several advantages. Firstly, it is a drug-free method to activate locomotor networks allowing us to rapidly turn on locomotor networks for short periods. Secondly, because this method relies entirely on dorsal root stimulation, it forms an endogenous self-contained circuit for activating spinal CPGs. This provides us with the opportunity to examine spinal CPG performance in the presence and absence of descending modulatory activity from bulbospinal centres. Here we test the hypothesis that bulbospinal activity can modulate afferent-evoked spinal CPG activity before the onset of weight-bearing locomotion. Portions of the data have been published in abstract form (Gordon & Whelan, 2004).

Methods

Experiments were performed on Swiss–Webster mice (Charles River Laboratories) 1–2 days old (P1–P2). The animals were anesthetised by cooling, decapitated and eviscerated using procedures approved by the University of Calgary Animal Care Committee. The remaining tissue was placed in a dissection chamber filled with oxygenated (95% O2, 5% CO2) artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF; in mm: 128 NaCl, 4 KCl, 1.5 CaCl2, 1 MgSO4, 0.5 Na2HPO4, 21 NaHCO3, 30 d-glucose). A ventral laminectomy exposed the spinal cord sparing as much of the cauda equina as possible, and the ventral and dorsal roots were cut. The cord was transected at the medullary-spinal junction (C1) and then was gently removed from the vertebral column. In sets of preliminary experiments requiring the brainstem, the transection was made at cranial nerve IX. For the remainder of experiments requiring a brainstem, the transection was made at cranial nerve VII to include more of the monoaminergic nuclei and to conform to previously published brainstem studies (Zaporozhets et al. 2004). The cerebellum was also dissected away. The brainstem–spinal cord or isolated spinal cord was then allowed to recover for at least 30 min before being transferred to the recording chamber and superfused with oxygenated (95% O2, 5% CO2) ACSF. The bath solution was heated gradually from room temperature to 27°C. The preparation was then allowed to equilibrate for at least 30 min. In certain experiments, the brainstem and spinal cord were separately superfused. The ACSF in the brainstem compartment was replaced with a precooled high sucrose ACSF (in mm: 25 NaCl, 1.9 KCl, 10 MgSO4, 1.2 Na2HPO4, 26 NaHCO3, 25 d-glucose, 188 sucrose) and maintained at ∼10°C. Thermometers were placed in each split-bath compartment to monitor temperature. The bath was divided by a piece of thin plastic, sealed with petroleum jelly around the spinal cord at C1. Green food colour was added to the circulating solution on one side of the split-bath to ensure the seal was complete. If the dye leaked to the adjoining chamber the experiment was aborted.

Electrophysiological recordings and activation of locomotor networks

Neurograms were recorded with suction electrodes into which segmental ventral roots were drawn. Generally, neurograms were recorded from the following ventral roots: the left and right lumbar 2 (L2) ventral roots, an L5 ventral root, and in select experiments, a sacral 4 (S4) root as well. The neurograms were amplified (100–20 000 times), filtered (100 Hz to 1 kHz or DC–1 kHz) and digitized (Axon Instruments Digidata 1322A) for future analysis. Alternating segmental and ipsilateral ventral root bursting patterns were taken to be indicative of fictive locomotion (Whelan et al. 2000). Constant current stimulus trains (A360 World Precision Instruments, AMPI Master 8 pulse generator) were delivered to coccygeal roots via a suction electrode. To determine the stimulus threshold (T), single pulses were delivered at increasing intensities until a polysynaptic reflex response was elicited (2–10 μA). Pulses were delivered every 3 min (4 Hz, 40 pulses, T–3T range, 1 ms pulse duration) at a constant intensity throughout an experiment (Whelan et al. 2000). Control rhythms were recorded for 15 min before lesions were performed, pharmacological agents were added or high sucrose ACSF replaced the bath ACSF. All lesions were performed with the preparation in the chamber. The time taken to complete a lesion procedure ranged from less than 3 min for complete transections at the medullary spinal cord junction to 10–20 min for discrete VLF lesions. The evoked rhythm was recorded for another 30–45 min under these new conditions. In some experiments 500–1000 ml of preheated and oxygenated ACSF was then washed through the system, and 30–60 min of washout sweeps recorded. Temperature data from the bath were stored in a separate channel during sweep acquisition.

Histology

Spinal cords on which VLF lesions were performed were immersion fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) after the electrophysiological recordings were complete. The spinal cords were then paraffin embedded and sliced into 6 μm thin sections on a microtome. A slice was taken every 60 μm and mounted onto poly l-lysine coated glass slides. These slices were then stained with haematoxylin and eosin and assessed for lesion size using bright field techniques. The slices with the largest lesions for each spinal cord were then photographed using a digital camera. To quantify the extent of the lesion, we calculated the area of the left and right VLF lesion and normalized this area to the area of the entire spinal cord slice (Image J software, NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA).

Data analyses

Data were analysed using custom written programs (MatLab, The MathWorks, Natick, MA, USA) and commercially available programs (Statistica, StatSoft, Tulsa, OK, USA). We extracted stimulated sections of data from the raw records. The extracted data were digitally high pass filtered at 100 Hz, rectified, and then low pass filtered (80–100 Hz) before being mathematically decimated. Data were demeaned and detrended before a cospectral density analysis comparing the segmental L2 root neurograms from each side was performed using the time series functions in Statistica 6.0. The cospectral density and primary frequency were determined as finding the minimum value of the cospectral density of the compared neurograms (online supplemental data, Supplementary Fig. 1). In our work the rhythm tended to be alternating, which resulted in a negative going peak centred on 0.8–1.2 Hz in the cospectral density plot (Supplementary Fig. 1). Changes in the cospectral density amplitude during a particular experiment are useful for quantifying changes in the stability and quality of the rhythm. On the other hand, the raw cospectral density is not useful for comparing rhythm quality between preparations. For ease of illustration, we calculated the absolute value of the cospectral trough. Phase was calculated by taking the frequency range representing 75% of the cospectral density minimum peak (typically centred on 0.8–1.2 Hz) and then computing the average phase value from the phase spectrum plot (Strauss & Lev-Tov, 2003). Phase and period values were not compared when the cospectral density was reduced below 10% of control. To measure the average long-latency polysynaptic potential (LLPP) elicited from cauda equina stimulation, we calculated the mean amplitude for a 10–200 ms window following the stimulus initiation and subtracted an average baseline value from 200 ms of data just before stimulation. To improve the clarity of the traces, we digitally removed the stimulus artifacts. In experiments where we lesioned the VLF tracts, we plotted the cycle period and cospectral density values against the total lesioned area of the spinal cord.

Statistics

Control and trial conditions were compared using a before and after t test and significance was set at P < 0.05 (SigmaStat, Systat, San Jose, CA, USA). For multiple comparisons we used a repeated measures one-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey's post hoc test to detect significant differences where P < 0.05 (SigmaStat).

Results

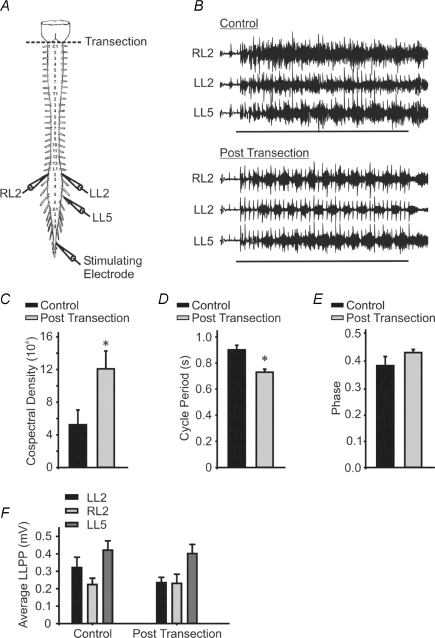

Brainstem transection increases the stability and burst frequency of sensory evoked locomotion

Generally, afferent-evoked locomotor-like activity using brainstem–spinal cord preparations was less robust than those obtained using isolated spinal cord preparations. Within a given set of trials, one would observe a mixture of tonic activity, accompanied by trials where the rhythmic activity was often not coordinated. However, it was possible to elicit locomotor-like patterns, and generally the frequency of these rhythms tended to be slower than those obtained using isolated thoracosacral spinal cord preparations (Fig. 1). To determine the effect of brainstem transection on afferent-evoked locomotor activity, we first recorded control rhythms from the isolated brainstem–spinal cord preparation (Fig. 1B). The spinal cord was then transected at the level of C1 and a minimum of 30 more minutes of activity was recorded. Brainstem transection increased the modulatory depth and stability of rhythmic activity as reflected by the significant increase in cospectral density between the L2 neurograms (n = 7, P < 0.05, Fig. 1C). Following brainstem transection the cycle period of the afferent-evoked rhythm decreased (n = 7, P < 0.05, Fig. 1D), while the phase was unaffected (n = 7, P > 0.1, Fig. 1E). The LLPP was not significantly different (n = 7, P > 0.1, Fig. 1F). The LLPP provides a measure of modulation of brainstem activity on polysynaptic reflexes. Since it is measured directly after the first pulse in a train, it measures modulation of reflex amplitude independent of network activation. Transection of the brainstem–spinal cord at the C1 segment resulted in a qualitative change in the rhythm as soon as the next stimulus train occurred (∼3 min following transection). The effects were also long-lasting; the pattern remained qualitatively similar for the duration of the experiment (∼2 h).

Figure 1. Brainstem transection modulates afferent-evoked rhythmicity.

A, schematic diagram of the isolated brainstem–spinal cord showing recording and stimulation sites. The dotted line indicates the level of transection. B, representative traces illustrating the effect of brainstem transection on afferent-evoked rhythmicity. Horizontal lines represent the duration of the 10 s stimulus train. Stimulus trains were delivered every 3 min. C–F, graphs show the cospectral density values (C), the cycle period (D), the phase (E) and the average LLPP (F) before and after transection. *Significant difference from control (n = 7, P < 0.05). Error bars represent s.e.m.

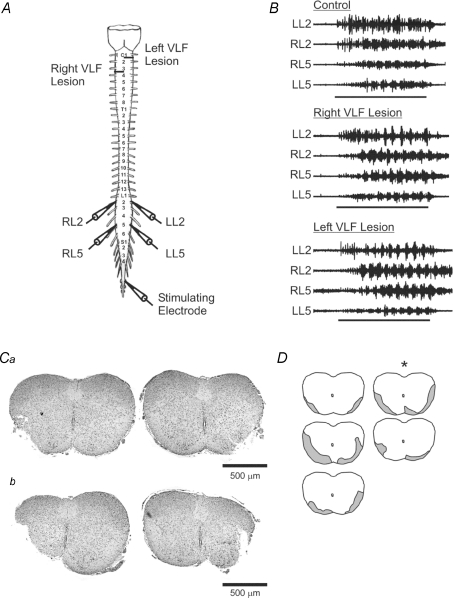

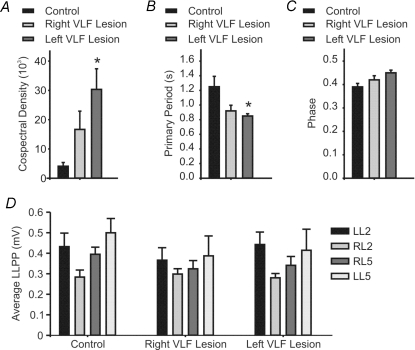

Specific VLF lesions mimic the effects of complete transection on sensory evoked locomotion

Next we tested whether specific lesions of the VLF could mimic the effects of a complete transection. As before, control sweeps were recorded from the isolated brainstem–spinal cord. As reported earlier, the quality of the rhythm under control conditions was mixed. Afterwards a lesion of first the right and then the left VLF was made at different cervical levels to allow for future assessment of the extent of the lesion (Fig. 2A). These ventral lesions led to a qualitative improvement in the quality of the rhythm (Fig. 2B). Overall, the stability and modulatory depth of the rhythm increased progressively following each of the VLF lesions. After both the left and right lesions were made, the cospectral density was significantly increased (n = 5, P < 0.05, Fig. 3A) and the cycle period was significantly decreased (n = 5, P < 0.05, Fig. 3B). Once again the phase and LLPP were unaffected (n = 5, P > 0.1, Fig. 3C and D). Our post hoc haematoxylin and eosin histology confirmed that we had lesioned portions of the right and left VLF (Fig. 2C and D). We calculated the extent of the right (6.5 ± 2.3%, n = 5, range 2.3–15.3%) and left (5.9 ± 2.7%, n = 5, range 3.0–9.0%) VLF lesion relative to the intact spinal cord slice in each of the five cords tested. While the extent of the lesions differed from one preparation to the next (Fig. 2D), there were common areas of the VLF lesioned. The representative traces in Fig. 2B correspond to the starred lesion area in Fig. 2D. Given the differences in lesion area between preparations, we next examined whether any correlation between lesion size and the magnitude of the effects on cospectral density and cycle period would be evident. The percentage lesion value for the right side was plotted against the average cospectral amplitudes (average of 5 sweeps) for each preparation. Next the percentage lesion values for the left and right were summed and these values were then plotted against the respective cospectral density and cycle period values. These analyses revealed no correlation between lesion size and rhythm stability or cycle period (r2 = 0.00 for both; slope not significantly > 0 (P > 0.1)).

Figure 2. Discrete VLF lesions mimic the effect of complete brainstem transection.

A, schematic diagram of the isolated brainstem–spinal cord showing recording and stimulation sites. Horizontal lines represent the levels of the two lesion sites. B, representative traces illustrating the effects of VLF lesions on afferent-evoked rhythmicity. The right VLF trace represents a right ipsilateral lesion. The left VLF trace represents activity after both ipsilateral and contralateral sides were lesioned. Horizontal lines represent the duration of the 10 s stimulus train. C, haematoxylin- and eosin-stained 6 μm cervical spinal cord slices showing the left and right lesion sites for the cords with the smallest (a) and largest (b) lesions. D, schematic diagram of the lesion sizes and locations for each of the five cords in the experimental set. Shaded grey areas represent the lesioned portions of the spinal cord. The cord with an asterisk represents that shown in B.

Figure 3. The cospectral density and primary period of the afferent-evoked rhythmicity are both altered by discrete VLF lesions.

Graphs representing the mean cospectral density (A), primary period (B), phase (C) and average LLPP (D) under control conditions and after one side and then after both sides have received a lesion of the VLF. *Significant difference from control (n = 5, P < 0.05). Error bars represent s.e.m.

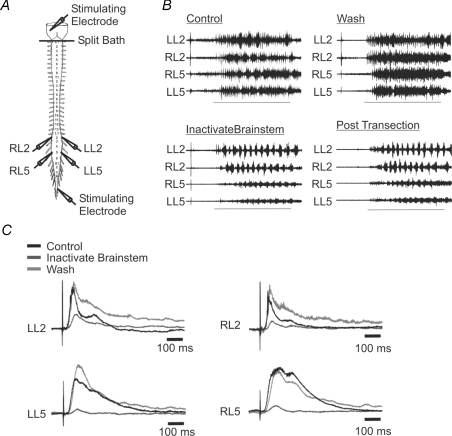

Inhibiting brainstem activity mimics the effects of complete brainstem transection

Transection of the spinal cord may have resulted in spinal shock that had some long-lasting effects on afferent transmission. To control for this possibility we designed a set of experiments to inhibit brainstem activity while the brainstem–spinal cord remained intact. A split-bath was placed at the level of C1 to allow for separate perfusion of the brainstem and the spinal cord. Additionally, a stimulating electrode, placed on the ventrolateral surface of the brainstem, was used to confirm a reduction in brainstem transmission to the spinal cord (Fig. 4A). Electrical stimulation of the brainstem with single pulses evoked robust potentials in the ventral root neurograms. Following cooling the peak amplitude of the brainstem evoked potentials was reversibly reduced (Fig. 4C, 250 ± 32 μV (control), 58 ± 29 μV (inactivate), 227 ± 42 μV (wash), P < 0.01, n = 4). The delay from the brainstem stimulus pulse to the onset of the L2 neurogram evoked response was 34.4 ± 3.8 ms under control conditions (n = 4). The length of the cord from the stimulus point to the L2 ventral root was approximately 17 mm. From these values the calculated conduction velocity was 0.49 m s−1.

Figure 4. Brainstem inactivation mimics the effect of complete brainstem transection.

A, schematic diagram of the isolated brainstem–spinal cord showing recording and stimulation sites and the location of the split bath, represented by a horizontal line. B, representative traces illustrating the effects of brainstem inactivation and brainstem transection on afferent-evoked rhythmicity. Horizontal lines represent the duration of the 10 s stimulus train. C, representative traces illustrating the effects of brainstem inactivation on ventral root potentials evoked by single brainstem stimulating pulses.

Thus, we were able to inhibit brainstem activity, by superfusing the brainstem with a high sucrose solution and reducing the brainstem bath temperature below 10°C (Fig. 4). We then applied this approach to examine whether cooling of the brainstem affected afferent-evoked rhythms. We found that this approach significantly affected the quality of the rhythm (Fig. 4B). The amplitude of the cospectral density increased suggesting an improvement in the regularity of the rhythm (n = 8, P < 0.05, Fig. 5A). The cycle period was also significantly reduced (n = 8, P < 0.05, Fig. 5B). As with transection, the phase and LLPP were unaffected (n = 8, P > 0.1, Fig. 5C and D).

Figure 5. The cospectral density and primary period of the afferent-evoked rhythmicity are both altered by brainstem inactivation.

Graphs representing the cospectral density (A), primary period (B), phase (C) and average LLPP (D) under control conditions, after brainstem inactivation via cooling to below 10°C and the circulation of a high sucrose solution, after washout and reheating and finally after brainstem transection. *Significant difference from control (n = 8, P < 0.05). Error bars represent s.e.m.

Discussion

The main result of this paper is that bulbospinal projections travelling within the ventrolateral funiculus (VLF) can modulate evoked locomotor activity in the neonatal mouse. Our work adds to other studies that demonstrate that electrical stimulation of the MLR, PLR and MRF regions of the brainstem activate spinal CPGs (Shik et al. 1969; McClellan & Grillner, 1984; Atsuta et al. 1990; Kinjo et al. 1990; Livingston & Leonard, 1990; Noga et al. 1991; Sirota et al. 2000). Here we adopted a different approach by stimulating cauda equina afferents and then examining brainstem modulation of the evoked rhythm. This approach has several advantages. Stimulating the coccygeal roots can reliably activate CPGs in short bouts for several hours and does not require the use of bath-applied drugs such as monoamines, or NMDA. Pinching (Lev-Tov et al. 2000; Whelan et al. 2000) or applying radiant heat to the tail (Blivis et al. 2007) in tail-attached in vitro preparations can evoke rhythms similar to afferent-evoked stimulation suggesting that this approach drives spinal CPGs in a physiologically relevant manner. Finally, by using split bath techniques, one can reversibly inactivate the brainstem, and examine how the output of the ongoing evoked spinal CPG pattern changes.

An important distinction between our work and previous studies is that we have determined that spontaneous activity within areas of the brainstem is sufficient to modulate ongoing locomotor activity. We used a variety of different cooling and transection procedures to support these conclusions. First we established that transection of the brainstem increased the frequency and modulatory depth of the rhythm. We then controlled for possible effects of spinal shock (Juvin et al. 2005) by reversibly suppressing neural activity in the brainstem. Finally we established, in separate experiments, that lesions of the VLF could produce similar effects as brainstem transection. The effect on modulatory depth and frequency of the rhythm suggests that the change in descending drive affected locomotor drive onto the CPG circuits. Qualitatively, following lesion or inactivation procedures the rhythm frequency and quality was similar to our previous work using cauda equina stimulation in the isolated spinal cord preparation (Whelan et al. 2000; Gordon & Whelan, 2006b). Data from other work demonstrate that lesions of the VLF in the cat can disrupt MLR evoked locomotor activity (Steeves & Jordan, 1980; Noga et al. 1991). Moreover stimulation of this region is effective in activating the spinal CPG in neonatal rat preparations (Atsuta et al. 1990; Kinjo et al. 1990). It has been known for some time that there are two main brainstem pathways that descend in the VLF and activate spinal CPGs (Jordan et al. 2008). The first region is located in a region known as the MLR that is close to the cuneiform and pedunculopontine nucleus in the rostral pons. The second region is the pontomedullary locomotor region, which projects from the medial MLR to the MRF and was originally thought to travel through the dorsolateral funiculus (DLF) to activate spinal CPGs (Mori et al. 1977). However, it is more likely that a substantial component travels through the VLF at least in the cat (Noga et al. 1991; Noga et al. 2003). Our work demonstrates that bilateral lesions of the VLF produce the greatest effects on the modulatory depth of the rhythm.

Indirect evidence from cat, rat and mouse preparations suggests that glutamatergic projections contribute to the initiation of locomotion since application of glutamatergic antagonists at the spinal cord level block locomotor activity under certain conditions (Douglas et al. 1993; Whelan et al. 2000), conduction velocities are consistent with propagation by myelinated fibres (Noga et al. 2003), and bath application of glutamate agonists can promote locomotor activity (Kudo & Yamada, 1987; Cazalets et al. 1992; Whelan et al. 2000). However, the identity of glutamatergic neurons or their target interneurons within the spinal cord has not been determined (Jordan et al. 2008). We are not aware of studies that have examined glutamatergic immunopositive cells in the MRF following retrograde labelling of the VLF in the mouse. We calculated the estimated conduction velocity of descending axons to be 0.49 m s−1. This conduction velocity is likely to represent slow conduction along intraspinal tracts since work by Burke and colleagues (Li & Burke, 2001) estimated the synaptic delay to be small (∼1 ms). Therefore, the slow conduction velocity is likely to be due to poorly developed myelination of the VLF at birth (Schwab & Schnell, 1989). Unfortunately, this makes this measure not particularly useful in discriminating between monoaminergic and fast conducting (glutamatergic) tracts in the neonatal mouse compared to the cat (Noga et al. 2003). On the other hand, serotonergic projections from the parapyramidal area of the brainstem have recently been found to be important for initiating locomotion (Liu & Jordan, 2005). In the mouse, monoaminergic systems descend in the VLF tract and this is particularly true of the noradrenergic system (VanderHorst & Ulfhake, 2006). Serotonergic descending projections show greater localization to the lateral and dorsolateral areas of the white matter (VanderHorst & Ulfhake, 2006). Retrograde labelling of spinal cord shows considerable labelling of MRF in mouse (VanderHorst & Ulfhake, 2006), but localization to the VLF is lacking. Interestingly, our previous work (Gordon & Whelan, 2006b) demonstrated that activation of either 5-HT2 or α1 adrenergic receptors decreased the frequency of the rhythm similar to what we observed when brainstem projections were intact. Our work combined with previous results from other vertebrate species (Jordan et al. 2008) makes it reasonable to hypothesize that multiple descending pathways contribute to the initiation and modulation of locomotor activity in the mouse.

The fact that the rhythm became more robust and the cycle period decreased while the long latency polysynaptic potential (LLPP) was unaffected suggests that the thoracosacral CPG network was a target of the brainstem modulation. However, this does not rule out the possibility that modulation of a wind-up mechanism at the level of the first order interneurons may contribute to the changes in the lumbar rhythm (Herrero et al. 2000). Indeed, this is a likely possibility since it is known that multiple descending pathways modulate nociceptive pathways (Millan, 2002) and recent data indicate a role for opiates in mediating sacrocaudal evoked locomotor activity (Blivis et al. 2007). A caveat in our interpretation is that work using the neonatal rat shows opiate effects on reflex amplitude were observed at longer latencies than used here, while shorter latencies similar to those used in our work showed modest changes in amplitude (Blivis et al. 2007). Nevertheless, our data show that at least some reflex pathways evoked by cauda equina stimulation are unaffected by brainstem inactivation or VLF transection.

While we have focused on the effects of descending projections, we must consider that spino-bulbo-spinal pathways are likely to contribute to the modulatory effects as they do in the cat (Shimamura & Livingston, 1963; Drew et al. 1996, 2004; Whelan, 1996). Many MRF cells are phasically active during fictive locomotion in the cat in a cycle dependent fashion (Perreault et al. 1993). Since these data were collected from preparations that were paralyzed, this suggests that a central pathway projects directly or indirectly onto the MRF. Consequently, there is reason to hypothesize that a functional pathway from the CPG onto the MRF is present in isolated mouse spinal cord preparations. Although previous work from our lab shows that cauda equina-evoked locomotor drive can project at least as far as cervical segments in the mouse (Gordon & Whelan, 2006a), future studies will need to confirm whether rhythmically active cells can be found in the MRF of the mouse.

In this work we have not considered the contribution of cervical segments to the modulation of lumbar patterns. Certainly, cervical segments receive locomotor drive from caudal segments in the mouse (Gordon & Whelan, 2006a) and work done in the neonatal rat shows that propriospinal pathways from cervical regions participate in conducting the bulbospinal excitatory drive onto thoracolumbar segments (Zaporozhets et al. 2006). Therefore, it is possible, if not likely, that cervical circuits propagate the descending modulatory signal from the brainstem in the mouse. It would be interesting to examine whether the ascending locomotor drive facilitates the transmission within cervical segments.

In conclusion, our work shows that activity of the brainstem can modulate afferent-evoked locomotor patterns. In particular, it demonstrates that bulbospinal pathways travelling though the VLF modulate afferent-evoked CPG output. Since this modulation occurs as a consequence of spontaneous brainstem activity, it implies that these descending pathways contribute to the control of spinal CPG circuits early in development (Norreel et al. 2003). In combination with genetic techniques (Gordon & Whelan, 2006a; Kiehn, 2006), we expect the type of approach outlined here holds considerable promise for elucidating the pathways and transmitters involved in the descending control of locomotion.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the excellent technical assistance of Michelle Tran. This research was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Christopher Reeve Paralysis Foundation, the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada and the Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research.

Supplementary material

Online supplemental material for this paper can be accessed at:

http://jp.physoc.org/cgi/content/full/jphysiol.2007.148320/DC1 and http://www.blackwell-synergy.com/doi/suppl/10.1113/jphysiol.2007.148320

References

- Atsuta Y, Garcia-Rill E, Skinner RD. Characteristics of electrically induced locomotion in rat in vitro brain stem-spinal cord preparation. J Neurophysiol. 1990;64:727–735. doi: 10.1152/jn.1990.64.3.727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beato M, Nistri A. Serotonin-induced inhibition of locomotor rhythm of the rat isolated spinal cord is mediated by the 5-HT1 receptor class. Proc Biol Sci. 1998;265:2073–2080. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1998.0542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blivis D, Mentis GZ, O'Donovan MJ, Lev-Tov A. Differential effects of opioids on sacrocaudal afferent pathways and central pattern generators in the neonatal rat spinal cord. J Neurophysiol. 2007;97:2875–2886. doi: 10.1152/jn.01313.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cazalets JR, Sqalli-Houssaini Y, Clarac F. Activation of the central pattern generators for locomotion by serotonin and excitatory amino acids in neonatal rat. J Physiol. 1992;455:187–204. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp019296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowley KC, Schmidt BJ. A comparison of motor patterns induced by N-methyl-D-aspartate, acetylcholine and serotonin in the in vitro neonatal rat spinal cord. Neurosci Lett. 1994;171:147–150. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(94)90626-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douglas JR, Noga BR, Dai X, Jordan LM. The effects of intrathecal administration of excitatory amino acid agonists and antagonists on the initiation of locomotion in the adult cat. J Neurosci. 1993;13:990–1000. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-03-00990.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drew T, Cabana T, Rossignol S. Responses of medullary reticulospinal neurones to stimulation of cutaneous limb nerves during locomotion in intact cats. Exp Brain Res. 1996;111:153–168. doi: 10.1007/BF00227294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drew T, Prentice S, Schepens B. Cortical and brainstem control of locomotion. Prog Brain Res. 2004;143:251–261. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(03)43025-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Manira A, Pombal MA, Grillner S. Diencephalic projection to reticulospinal neurons involved in the initiation of locomotion in adult lampreys Lampetra fluviatilis. J Comp Neurol. 1997;389:603–616. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerin C, Becquet D, Privat A. Direct evidence for the link between monoaminergic descending pathways and motor activity. I. A study with microdialysis probes implanted in the ventral funiculus of the spinal cord. Brain Res. 1995;704:191–201. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)01111-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerin C, Legrand A, Privat A. Study of 5-HT release with a chronically implanted microdialysis probe in the ventral horn of the spinal cord of unrestrained rats during exercise on a treadmill. J Neurosci Methods. 1994;52:129–141. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(94)90121-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon IT, Whelan PJ. 2004 Abstract Viewer/Itinerary Planner. Washington, DC: Society for Neuroscience; 2004. Dopamine modulates afferent transmission to the spinal central pattern generator of the neonatal mouse. Program No. 883.5. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon IT, Whelan PJ. Deciphering the organization and modulation of spinal locomotor central pattern generators. J Exp Biol. 2006a;209:2007–2014. doi: 10.1242/jeb.02213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon IT, Whelan PJ. Monoaminergic control of cauda-equina-evoked locomotion in the neonatal mouse spinal cord. J Neurophysiol. 2006b;96:3122–3129. doi: 10.1152/jn.00606.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham-Brown T. The intrinsic factors in the act of progression in the mammal. Proc R Soc Lond. 1911;84:308–319. [Google Scholar]

- Grillner S. The motor infrastructure: from ion channels to neuronal networks. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2003;4:573–586. doi: 10.1038/nrn1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrero JF, Laird JM, Lopez-Garcia JA. Wind-up of spinal cord neurones and pain sensation: much ado about something? Prog Neurobiol. 2000;61:169–203. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(99)00051-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Z, Carlin KP, Brownstone RM. An in vitro functionally mature mouse spinal cord preparation for the study of spinal motor networks. Brain Res. 1999;816:493–499. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)01199-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan LM, Liu J, Hedlund PB, Akay T, Pearson KG. Descending command systems for the initiation of locomotion in mammals. Brain Res Rev. 2008;57:183–191. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2007.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan LM, Schmidt BJ. Propriospinal neurons involved in the control of locomotion: potential targets for repair strategies? Prog Brain Res. 2002;137:125–139. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(02)37012-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juvin L, Simmers J, Morin D. Propriospinal circuitry underlying interlimb coordination in mammalian quadrupedal locomotion. J Neurosci. 2005;25:6025–6035. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0696-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiehn O. Locomotor circuits in the mammalian spinal cord. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2006;29:279–306. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.29.051605.112910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinjo N, Atsuta Y, Webber M, Kyle R, Skinner RD, Garcia-Rill E. Medioventral medulla-induced locomotion. Brain Res Bull. 1990;24:509–516. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(90)90104-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kudo N, Yamada T. N-methyl-D,L-aspartate-induced locomotor activity in a spinal cord-hindlimb muscles preparation of the newborn rat studied in vitro. Neurosci Lett. 1987;75:43–48. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(87)90072-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lev-Tov A, Delvolve I, Kremer E. Sacrocaudal afferents induce rhythmic efferent bursting in isolated spinal cords of neonatal rats. J Neurophysiol. 2000;83:888–894. doi: 10.1152/jn.2000.83.2.888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Burke RE. Short-term synaptic depression in the neonatal mouse spinal cord: effects of calcium and temperature. J Neurophysiol. 2001;85:2047–2062. doi: 10.1152/jn.2001.85.5.2047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Jordan LM. Stimulation of the parapyramidal region of the neonatal rat brainstem produces locomotor like activity involving spinal 5-HT7 and 5-HT2A receptors. J Neurophysiol. 2005;94:1392–1404. doi: 10.1152/jn.00136.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livingston CA, Leonard RB. Locomotion evoked by stimulation of the brain stem in the Atlantic stingray, Dasyatis sabina. J Neurosci. 1990;10:194–204. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.10-01-00194.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madriaga MA, McPhee LC, Chersa T, Christie KJ, Whelan PJ. Modulation of locomotor activity by multiple 5-HT and dopaminergic receptor subtypes in the neonatal mouse spinal cord. J Neurophysiol. 2004;92:1566–1576. doi: 10.1152/jn.01181.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClellan AD, Grillner S. Activation of ‘fictive swimming’ by electrical microstimulation of brainstem locomotor regions in an in vitro preparation of the lamprey central nervous system. Brain Res. 1984;300:357–361. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(84)90846-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millan MJ. Descending control of pain. Prog Neurobiol. 2002;66:355–474. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(02)00009-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori S, Shik ML, Yagodnitsyn AS. Role of pontine tegmentum for locomotor control in mesencephalic cat. J Neurophysiol. 1977;40:284–295. doi: 10.1152/jn.1977.40.2.284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimaru H, Takizawa H, Kudo N. 5-Hydroxytryptamine-induced locomotor rhythm in the neonatal mouse spinal cord in vitro. Neurosci Lett. 2000;280:187–190. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(00)00805-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noga BR, Kettler J, Jordan LM. Locomotion produced in mesencephalic cats by injections of putative transmitter substances and antagonists into the medial reticular formation and the pontomedullary locomotor strip. J Neurosci. 1988;8:2074–2086. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.08-06-02074.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noga BR, Kriellaars DJ, Brownstone RM, Jordan LM. Mechanism for activation of locomotor centers in the spinal cord by stimulation of the mesencephalic locomotor region. J Neurophysiol. 2003;90:1464–1478. doi: 10.1152/jn.00034.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noga BR, Kriellaars DJ, Jordan LM. The effect of selective brainstem or spinal cord lesions on treadmill locomotion evoked by stimulation of the mesencephalic or pontomedullary locomotor regions. J Neurosci. 1991;11:1691–1700. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-06-01691.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norreel JC, Pflieger JF, Pearlstein E, Simeoni-Alias J, Clarac F, Vinay L. Reversible disorganization of the locomotor pattern after neonatal spinal cord transection in the rat. J Neurosci. 2003;23:1924–1932. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-05-01924.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearlstein E, Mabrouk FB, Pflieger JF, Vinay L. Serotonin refines the locomotor-related alternations in the in vitro neonatal rat spinal cord. Eur J Neurosci. 2005;21:1338–1346. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.03971.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perreault MC, Drew T, Rossignol S. Activity of medullary reticulospinal neurons during fictive locomotion. J Neurophysiol. 1993;69:2232–2247. doi: 10.1152/jn.1993.69.6.2232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwab ME, Schnell L. Region-specific appearance of myelin constituents in the developing rat spinal cord. J Neurocytol. 1989;18:161–169. doi: 10.1007/BF01206659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shik ML, Severin FV, Orlovsky GN. Control of walking and running by means of electrical stimulation of the mesencephalon. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1969;26:549. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimamura M, Livingston RB. Longitudinal conduction systems serving spinal and brain-stem coordination. J Neurophysiol. 1963;26:258–272. doi: 10.1152/jn.1963.26.2.258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sirota MG, Di Prisco GV, Dubuc R. Stimulation of the mesencephalic locomotor region elicits controlled swimming in semi-intact lampreys. Eur J Neurosci. 2000;12:4081–4092. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2000.00301.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JC, Feldman JL. In vitro brainstem-spinal cord preparations for study of motor systems for mammalian respiration and locomotion. J Neurosci Methods. 1987;21:321–333. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(87)90126-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steeves JD, Jordan LM. Localization of a descending pathway in the spinal cord which is necessary for controlled treadmill locomotion. Neurosci Lett. 1980;20:283–288. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(80)90161-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss I, Lev-Tov A. Neural pathways between sacrocaudal afferents and lumbar pattern generators in neonatal rats. J Neurophysiol. 2003;89:773–784. doi: 10.1152/jn.00716.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VanderHorst VG, Ulfhake B. The organization of the brainstem and spinal cord of the mouse: relationships between monoaminergic, cholinergic, and spinal projection systems. J Chem Neuroanat. 2006;31:2–36. doi: 10.1016/j.jchemneu.2005.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whelan PJ. Control of locomotion in the decerebrate cat. Prog Neurobiol. 1996;49:481–515. doi: 10.1016/0301-0082(96)00028-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whelan P, Bonnot A, O'Donovan MJ. Properties of rhythmic activity generated by the isolated spinal cord of the neonatal mouse. J Neurophysiol. 2000;84:2821–2833. doi: 10.1152/jn.2000.84.6.2821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaporozhets E, Cowley KC, Schmidt BJ. A reliable technique for the induction of locomotor-like activity in the in vitro neonatal rat spinal cord using brainstem electrical stimulation. J Neurosci Methods. 2004;139:33–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2004.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaporozhets E, Cowley KC, Schmidt BJ. Propriospinal neurons contribute to bulbospinal transmission of the locomotor command signal in the neonatal rat spinal cord. J Physiol. 2006;572:443–458. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.102376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.