Abstract

We previously showed that degradation of cellular sphingomyelin (SM) by SMase C results in a greater stimulation of cholesterol translocation to endoplasmic reticulum, compared to its degradation by SMase D. Here we investigated the hypothesis that the effect of SMase C is partly due to the generation of ceramide, rather than due to depletion of SM alone. Inhibition of hydroxymethylglutaryl CoA reductase (HMGCR) activity was used as a measure of cholesterol translocation. Treatment of fibroblasts with SMase C resulted in a 90% inhibition of HMGCR, whereas SMase D treatment inhibited it by 29%. Treatment with exogenous ceramides, or increasing the endogenous ceramide levels also inhibited HMGCR by 60–80%. Phosphorylation of HMGCR was stimulated by SMase C or exogenous ceramide. The effects of ceramide and SMase D were additive, indicating the independent effects of SM depletion and ceramide generation. These results show that ceramide regulates sterol trafficking independent of cellular SM levels.

Keywords: Sphingomyelin, Ceramide, ACAT, HMG CoA reductase, Sterol trafficking

Introduction

The distribution of sphingomyelin among the various cellular membranes is remarkably similar to that of cholesterol, and the two membrane lipids are known to specifically interact with each other [1,2]. Their co-localization in the membrane rafts, and their effects on each other’s metabolism [3] suggest a regulatory function for SM in cholesterol homeostasis in cells. Several studies showed that hydrolysis of plasma membrane SM by bacterial SMase C (which degrades it to ceramide) results in a rapid translocation of plasma membrane cholesterol to endoplasmic reticulum (ER), as evident from the stimulation of acyl CoA: cholesterol acyltransferase (ACAT) reaction [4,5]. Our previous studies in human foreskin fibroblasts showed that unlike the effect of SMase C, treatment of the cells with SMase D (which degrades SM to ceramide phosphate) results in relatively modest stimulation of ACAT, although the extent of SM hydrolysis by the two enzymes was comparable [6]. This raised the possibility that the cellular response to SMase C treatment with respect to cholesterol trafficking is at least partly due to the generation of ceramide rather than the loss of SM alone from the PM.

It is well established that ceramide has several signaling effects in cells, including activation of ceramide activated protein kinase, protein kinase Cξ, and protein phosphatases [7]. Moreover, intracellular cholesterol transport has been shown to be regulated by protein phosphorylation [8,9], and the rate-limiting step in cholesterol synthesis, namely HMG CoA reductase activity, is known to be regulated by phosphorylation and dephosphorylation of the enzyme [10,11]. Exogenous C2-ceramide, as well as endogenous ceramides have been shown to increase cholesterol efflux to apoprotein A–I, primarily by increasing the amount of ATP-binding cassette transporter A1 [12], and to selectively displace cholesterol from membrane rafts [13] [14]. A previous study in rat astrocytes by Ito et al [15], however, reported no significant effect of exogenous ceramide on apo A–I-mediated cholesterol efflux. In the present study we tested the hypothesis that endogenous or exogenous ceramides modulate intracellular cholesterol trafficking (and) or the activity of enzymes of cholesterol homeostasis, independent of membrane SM concentration.

Direct measurement of cholesterol levels in ER is difficult because of the low concentration of cholesterol, and possible contamination with plasma membrane which has high cholesterol levels. Therefore, the movement of cholesterol from PM to ER is measured indirectly by determining the activation of ACAT activity, which is regulated by the ER cholesterol levels [4,6]. However, exogenous ceramide is known to inhibit this enzyme both in cell-free systems and in intact cells [6,16], and therefore, we employed the inhibition of HMG CoA reductase (HMGCR) activity as a measure of ER cholesterol levels in response to altered ceramide levels in the cells. This enzyme has also been shown to respond rapidly to variations in plasma membrane concentrations [17] [18], showing that its inhibition can be used as an alternate measure of ER cholesterol. The results presented here show that both exogenous and endogenous ceramides modulate the HMGCR activity independent of the membrane SM levels. Furthermore, part of the effects of ceramide on the enzyme appear unrelated to the increase in ER cholesterol, indicating an independent effect on sterol homeostasis.

Materials and methods

Materials

Synthetic sphingolipids (C2–C8 ceramides, and C2 and C8 ceramide phosphates) were purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids (Alabaster, AL, USA). Egg ceramide, H89 (N-[2-(p-bromocinnamylamino) ethyl]-5- isoquinolinesulfonamide), 6DMAP (6-dimethyl aminopurine), SMase C from S. aureus (120 U/mg) and cyclosporine were products of Sigma Chemical Co (St. Louis, MO, USA). U18666A (3β- (2-diethylamino ethoxy) androstenone) and were obtained from Calbiochem (La Jolla, CA, USA). DMAPP (1S,2R)-D-erythro-2-(N-myristoylamino)-1-phenyl-1-propanol) was purchased from Biomol (Plymouth Meeting, PA, USA). SMase D was purified from E.Coli transfected with the C. pseudotuberculosis SMase D by affinity chromatography, as described earlier [6]. The transfected E. Coli were obtained from Dr. Stephen Billington, University of Arizona. cholesterol [4-14C], specific activity 54 mCi/mmol), [14C]-HMG CoA (glutaryl-[3-14C], 55 mCi/mmol), and ATP-γ-[32P] (6000 Ci/mmol) were purchased from American Radiolabeled Chemicals, Inc (St. Louis, MO, USA). Antibody for HMGCR, and protein A agarose were purchased from Millipore (Billerica, MA).

Cell Culture

Human foreskin fibroblasts (obtained from Dr. Yvonne Lange, Rush University Medical Center, Chicago) were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM) containing 10% fetal bovine serum and 100 µg/ml each of streptomycin and penicillin.

Cholesterol esterification assay (ACAT)

ACAT activity in intact cells was measured by the conversion of labeled cholesterol to CE as described previously [6]. Briefly, the cells were labeled in 6 well (35 mm) plates with [4-14C] cholesterol by incubation with 0.1 µCi of labeled cholesterol complexed with 20% 2-hydroxypropyl β-cyclodextrin (HPCD) (final concentration of HPCD, 0.05%) for 10 min at room temperature. After removing the labeling buffer, and rinsing the cell monolayer with DMEM, 5% LPDS in DMEM containing was added to each well, and incubated for 2 h at 37° C in the presence or absence of various effectors (ceramides, SMases, inhibitors). The cells were then trypsinized, transferred to glass tubes, and extracted with 5 ml of chloroform: methanol (2:1 v/v). The chloroform extract was separated on silica gel TLC plate with the solvent system of hexane: ethyl acetate (90: 10 v/v), and the radioactivity in cholesterol and cholesteryl ester spots was determined in a liquid scintillation counter. The percent of cholesterol esterified was calculated from the radioactivity values.

HMG CoA reductase (HMGCR) activity

This enzyme activity was measured essentially as described by Brown et al [19], with a few modifications. The cells were incubated with 5% LPDS in DMEM overnight to up-regulate the enzyme activity, and then subjected to various treatments (SMases, ceramides, inhibitors) in LPDS medium for the indicated periods of time. Where indicated, the ceramides were added in ethanol, with the final concentration of ethanol at 0.5% in the medium. The cells were lysed as described [19] except for the use of Triton X100 as the detergent, and inclusion of 50 mM NaF and 10 mM DTT. The cell extract (10–15 µg protein) was incubated with glucose 6 phosphate, glucose 6 phosphate dehydrogenase and labeled HMG CoA [19] for 20 min at 37 C and the reaction was stopped by the addition of 10 µl of 5N HCl. The reaction mixture was directly loaded onto a silica gel TLC plate and separated using the solvent system of acetone: benzene (1:1). The band corresponding to mevalonate was identified by counting 1 cm segments on one lane, and the corresponding band was scraped and counted in the rest of the lanes. The enzyme activity was expressed as dpm converted to mevalonate per µg protein per h.

Phosphorylation of HMGCR

The phosphorylation of HMGCR was determined essentially as described by Gillespie and Hardie [20]. Briefly, the human skin fibroblasts were treated with SMase C (0.12 U/ml) or C6 ceramide (50 µM) for 2 h in DMEM containing 32P phosphate (50 µCi/ml). The cells were then washed, homogenized in the hypotonic buffer containing the protease inhibitors [20], lysed by repeated passage through a 21 gauge needle, and the microsopmes were prepared by centrifugation. The microsomes were dissolved in the immunoprecipitation buffer [20] and incubated with 10 µl antibody for 2 h at 40C with gentle shaking, followed by the addition of 50 µl Protein A agarose and further incubation for 2 h. The beads were separated by centrifugation and the bound proteins subjected to SDS electrophoresis 5–15% agarose. The proteins were then transferred to nitrocellulose membrane and the amount of label in the band corresponding to HMGCR measured in a phosphorimager (Storm 860, Molecular Dynamics).

Analytical

Protein was estimated by the Bio-Rad procedure [21], using BSA as the standard. The amount of SM degraded by the SMases was determined from the decrease in cell SM. Phospholipids were separated on silica gel TLC plates with the solvent system of chloroform: methanol: water (65:25:4 v/v), and lipid phosphorus in SM spots was estimated by the modified Bartlett procedure [22]. Ceramide levels in the cells was determined by the diacylglycerol kinase assay, as described by Bollag and Griner [23].

Results

Effect of SMases on ACAT and HMGCR activities

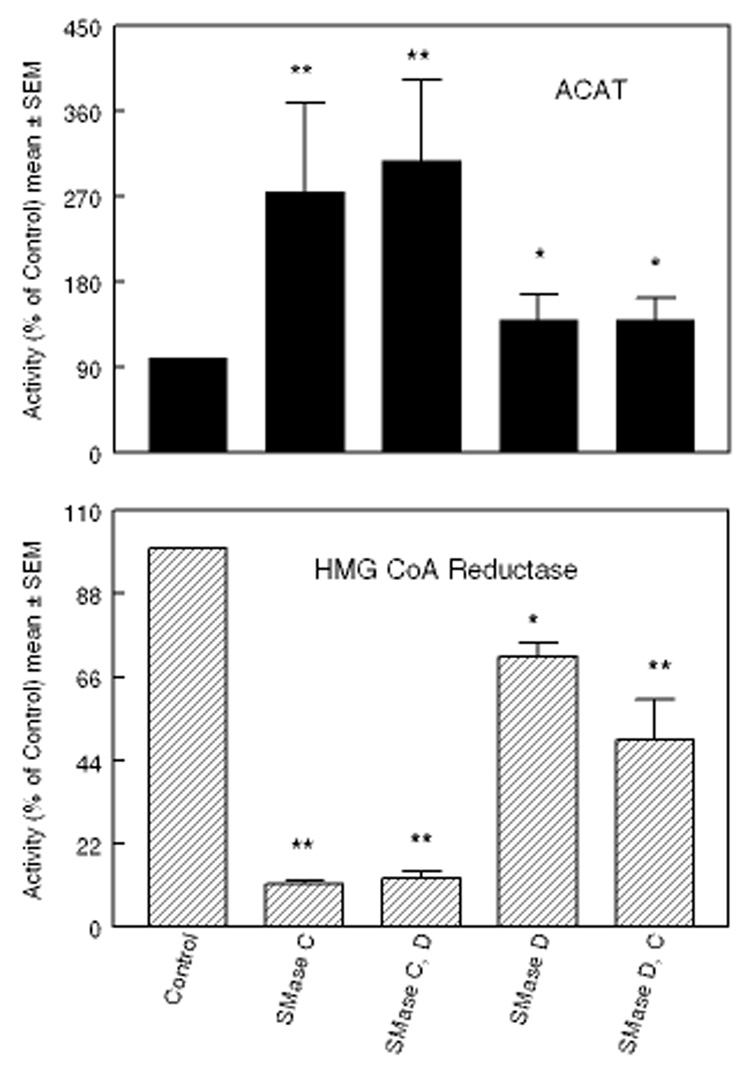

Our previous studies showed that treatment of fibroblasts with SMase C increased the translocation of PM cholesterol to ER by 4-fold, as measured by the stimulation of ACAT activity, compared to only a 70% stimulation by SMase D [6]. Since the percent of SM hydrolyzed by the two enzymes was comparable, we proposed that the greater response to SMase C treatment may be partly due to the generation of the cytoactive ceramide, which affected either cholesterol trafficking or the enzyme activity. The direct testing of this hypothesis was not possible using the ACAT activity, because exogenous ceramides strongly inhibit this enzyme in intact cells as well as in cell-free homogenates [6,24]. Therefore we sought another method to measure the enrichment of ER cholesterol, namely the suppression of HMGCR activity, which has also been shown to be exquisitely sensitive to ER cholesterol levels [17] [18]. The results presented in Fig. 1 show that the effect of SMase treatment on HMGCR activity was, as expected, opposite to that on ACAT activity. SMase C treatment of the cells inhibited HMGCR by about 90%, whereas it stimulated ACAT activity by 3-fold. Treatment with SMase D elicited a milder response, inhibiting HMGCR by 29% and activating ACAT by 40%. As reported earlier [6], the percent of cellular SM degraded was comparable with the two enzymes (about 65% of total SM, results not shown). Sequential treatment of the cells with SMase D followed by SMase C did not further increase ACAT activity, although it decreased HMGCR activity by another 20%. Sequential treatment with SMase C followed by SMase D also did not change the enzyme activities further. These results show that both enzymes hydrolyzed essentially the same pool of membrane SM, and that most of the accessible SM is hydrolyzed by both. They also suggest that the formation of ceramide is necessary for the maximal effect, because initial treatment with SMase D, precludes the formation of ceramide by the subsequent treatment with SMase C.

Figure 1. Effect of treatment with SMases C and D on ACAT and HMG CoA reductase (HMGCR) activities in fibroblasts.

Confluent layers of human skin fibroblasts (35 mm wells) were treated with either SMase C (0.12 U/ml) or SMase D (0.2 U/ml) in 5% LPDS-DMEM for 2 h at 37 °C. In some cases the cells were treated sequentially with both SMases (SMase C followed by SMase D, or SMase D followed SMase C). They were rinsed after 2 h treatment with the first enzyme, and then incubated with the second SMase for an additional 2 h. Cholesterol esterification (ACAT) and HMGCR activities were then assayed as described under Methods. When ACAT was assayed, the cells were pre-labeled with [4-14C]- cholesterol before incubation with the SMases. All activities are expressed as percent of the activity in control cells, which were untreated. The values shown are mean ± SEM of 3 separate experiments. * p< 0.05; ** p<0.005, compared to control.

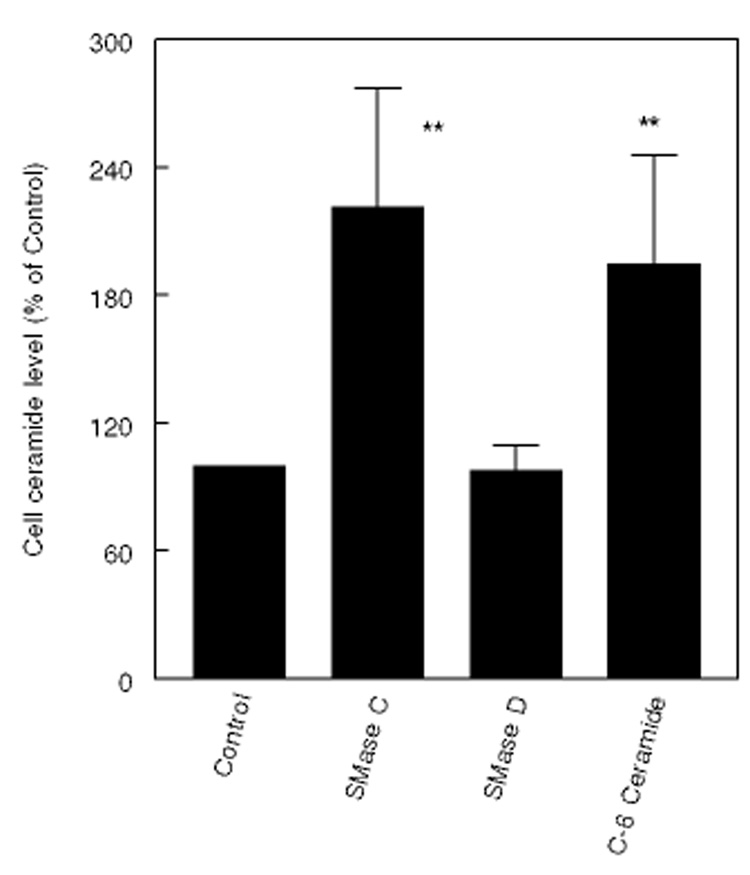

Fig. 2 shows the ceramide levels in cells after treatment with SMase C or D, or after incubation with exogenous short chain ceramide. As expected, the ceramide levels doubled after treatment with SMase C or with exogenous C6 ceramide, but not after treatment with SMase D.

Figure 2. Effect of SMases and exogenous ceramide on cellular ceramide levels.

Fibroblasts were treated with SMase C (0.12 U/ml), SMase D (0.2 U/ml), or C-6 ceramide (50 µM) for 2 h, and the cellular ceramide levels were determined by the diacylglycerol kinase assay [23]. ** p< 0.005, compared to control.

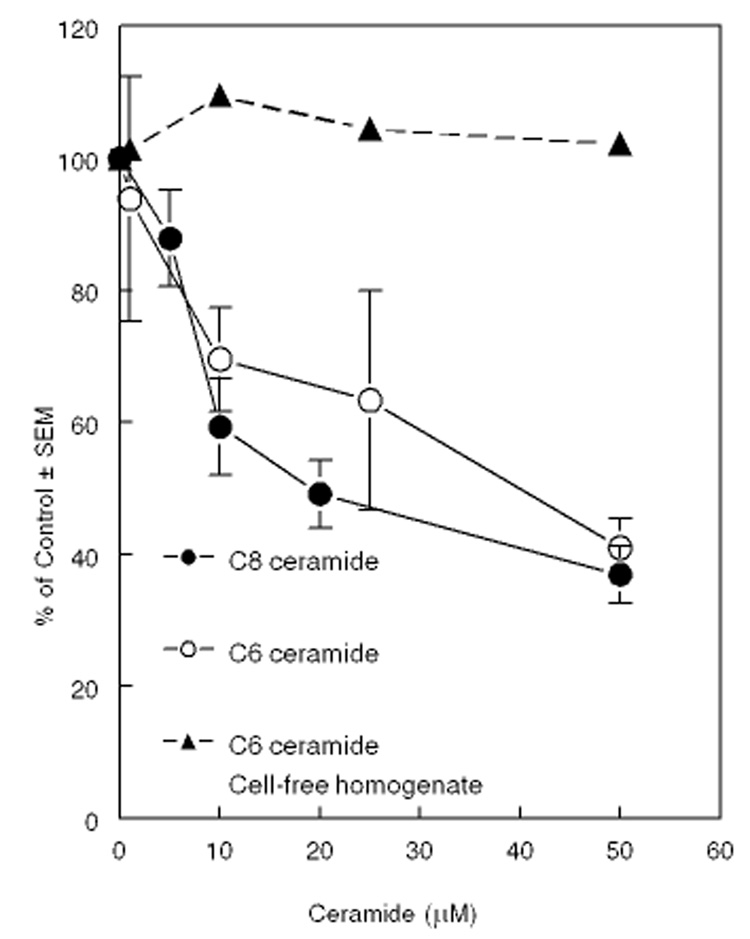

Effect of exogenous ceramides on HMGCR

When the cells were exposed (for 4 h) to varying concentrations of cell permeable C6 or C8 ceramide, there was a progressive decrease in HMGCR activity (Fig. 3). Addition of C6 ceramide to the cell-free homogenate did not inhibit the activity even at the highest concentration tested (50 µM), showing that unlike ACAT, HMGCR is not inhibited directly by ceramides. Since these cells have normal levels of SM, these effects can be attributed to ceramide alone.

Figure 3. Effect of exogenous ceramides on HMGCR activity.

Cells were exposed to either C6 ceramide or C8 ceramide at the indicated concentration for 2 h, and then the HMGCR activity was assayed as described in the text. The ceramides were added in ethanol, with the final concentration of ethanol at 0.5%. The control dishes contained ethanol alone. The enzyme activities were also assayed in cell-free homogenate of untreated cells in the presence of indicated concentration of C6 ceramide, to determine the direct effect of ceramide on the enzyme. All values shown are mean ± SEM of 4 different experiments, except for the homogenate values, which are averages of two experiments.

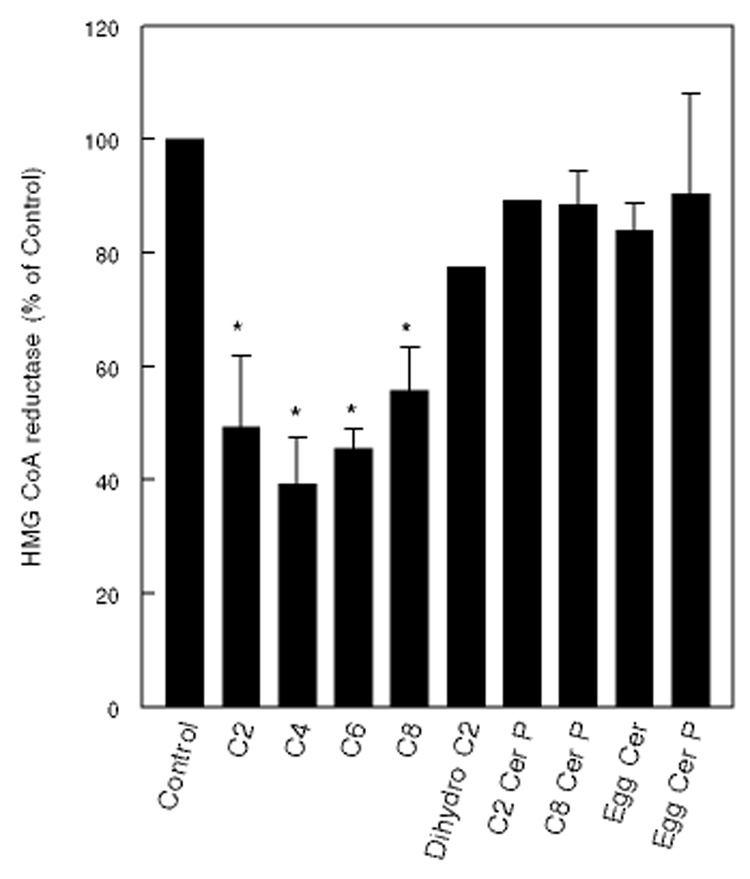

The specificity of ceramide effect is shown in Fig. 4. Short chain ceramides (C2 –C8) inhibited the activity by up to 60%, but long chain analog (egg ceramide) was ineffective, possibly because it is not cell permeable. C2 dihydroceramide, which is known to have no signaling effects, and has been used as an inert control for C2 ceramide [25,26], was much less effective than the trans unsaturated C2 ceramide. In contrast to the corresponding ceramides, C2- or C8-ceramide phosphate did not inhibit the enzyme activity, suggesting that the effect is specific for ceramide. Long chain ceramide phosphate prepared from egg SM was also ineffective. The lack of effect of ceramide phosphates is in agreement with lower response with SMase D treatment, compared to SMase C. The effect of short chain ceramides, however, did not equal that of SMase C, indicating that the depletion of endogenous SM by the enzyme has additional effect on HMGCR activity. Previous studies by Gupta and Rudney [27] reported that ceramide had no effect on HMCR activity. These authors did not, however, indicate whether they used short chain or long chain ceramide. The discrepancy in results may be explained if they have used the long chain ceramide, which does not enter the cell.

Figure 4. Specificity of ceramide effect.

Fibroblasts were treated with various ceramides or ceramide phosphates (50 µM each) for 2 h, and then the HMGCR activity was measured as described in the text. The compounds were added as ethanol solutions in 5% LPDS medium, with the final ethanol concentration at 0.5%. Values are expressed as percent of control (untreated cells) and are mean ± SEM of at least 3 experiments, where error bars are shown. The others are averages of 2 experiments. * p<0.05, compared to control (no ceramide).

Effect of endogenous ceramide

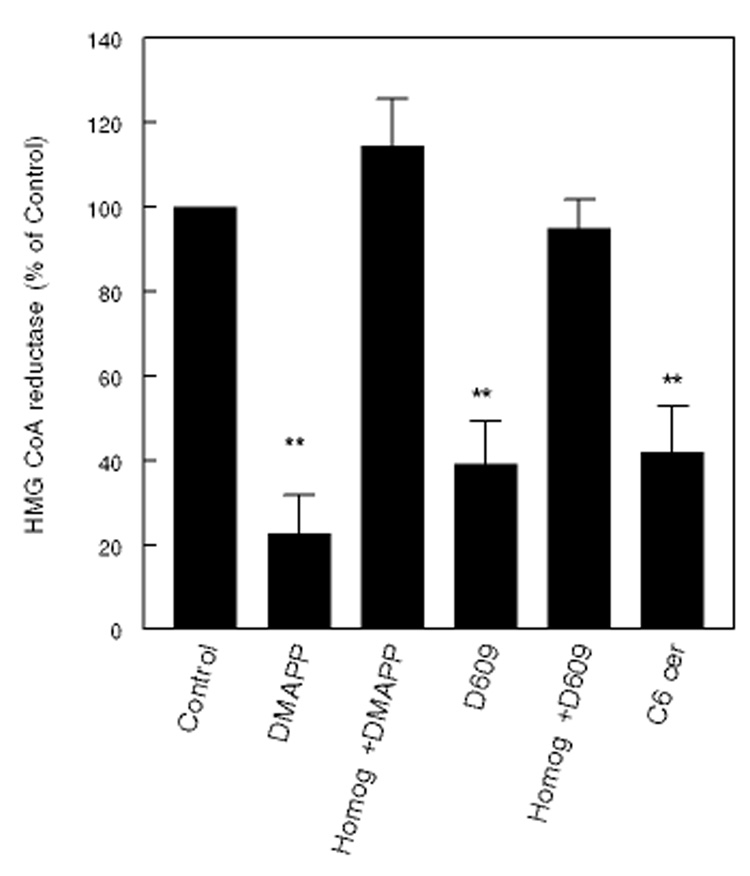

In contrast to treatment with exogenous SMase C, the intracellular ceramide levels can be increased without depleting the cellular SM, by inhibiting the normal cellular metabolism of ceramide. Cellular ceramide levels were increased by incubation of the fibroblasts with DMAPP, an inhibitor of ceramidase [28], or D609, an inhibitor of SM synthase [29]. As shown in Fig. 5, DMAPP inhibited HMGCR in intact cells by about 80%. It did not have any effect on the enzyme activity in the cell-free homogenate, showing that it does not directly inhibit HMGCR. D609 inhibited the enzyme to a lesser extent (60%). D609 also did not inhibit HMGCR in cell-free homogenates, in agreement with the previous reports [15]. The ceramide levels were increased by 20–80% by the inhibitor treatment, as determined by the diacylglycerol kinase assay (results not shown).

Figure 5. Effect of endogenous ceramide on HMGCR activity.

Human skin fibroblasts were incubated with 50 µM DMAPP (ceramidase inhibitor) overnight, 50 µg/ml D609 (an inhibitor of SM synthase) for 2 h, or with 50 µM C6 ceramide for 2h, and the cells were lysed and the HMGCR activity was measured. Control cells were untreated. The enzyme activity was also assayed in control cell lysate (Homog) in presence of 50 µM DMAPP or 50 µg/ml of D609, to determine the direct effect of the inhibitors. ** p<0.005, compared to control (no treatment).

Cellular ceramide levels are also known to be increased by the activation of neutral SMase by cytokines such as TNF-α [30]. To determine whether the ceramide generated by this pathway also inhibits HMGCR, we treated the fibroblasts ( for 2 h at 37 °C) with 10, 50, or 100 ng/ml TNF-α, and then determined the HMGCR activity in cell homogenate. There was about a 10% reduction in HMGCR after treatment with 100 ng/ml (statistically not significant). but no effect with lower concentration of TNF-α (results not shown). These results suggest that either the ceramide generated by this pathway is insufficient to affect HMGCR, or that it is present in a different cellular compartment. Previous studies in fact suggested that the pool of SM that is hydrolyzed by TNF-α treatment is different from that degraded by exogenous SMase C, and that it is regenerated in the plasma membrane itself [30].

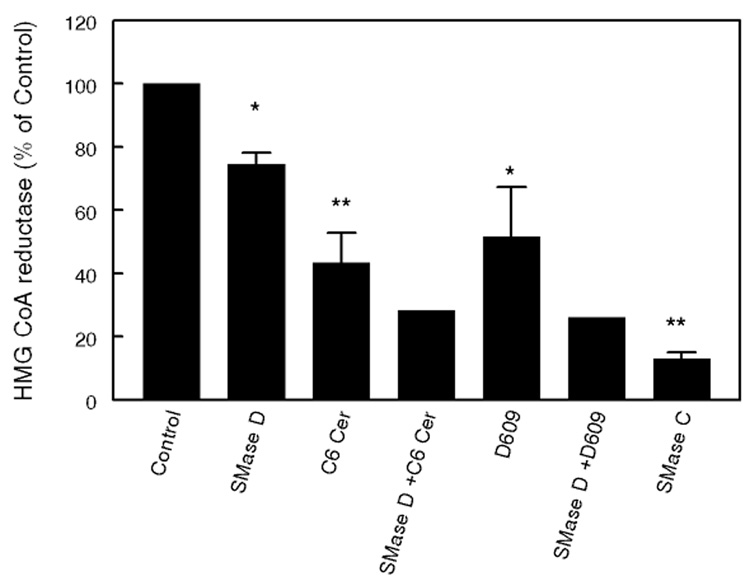

Additive effects of SMase D and ceramide

If the effect of SMase C treatment of the cells is due to the combined effects of SM depletion and ceramide generation, similar results should be obtained with a combination of SMase D and ceramide. We tested this possibility by increasing the cellular ceramide levels in addition to treatment with SMase D. As shown in Fig. 6, when the fibroblasts were treated with SMase D in presence of 50 µM C6 ceramide, the effect on HMGCR activity was greater than with either treatment alone. Similarly when the endogenous ceramide levels were raised by treatment with D609, the inhibition of HMGCR by SMase D treatment was significantly enhanced. These results support the hypothesis that the greater effect of SMase C on cholesterol trafficking, when compared to SMase D, is due to the combined effects of SM depletion and ceramide generation.

Figure 6. Additive effects of SMase D and ceramide.

Fibroblasts were treated with SMase D (0.2 U/ml) alone, or in combination with either C-6 ceramide (50 µM) or D609 (50 µg/ml) for 2 h, and the activity of HMGCR was determined as described in the text. For comparison, the effect of SMase C alone is also shown. The values shown are mean ± SEM of 3 experiments where error bars are shown. Others are averages of two separate experiments. * p< 0.05; ** p<0.005, compared to control.

Mechanism of ceramide action

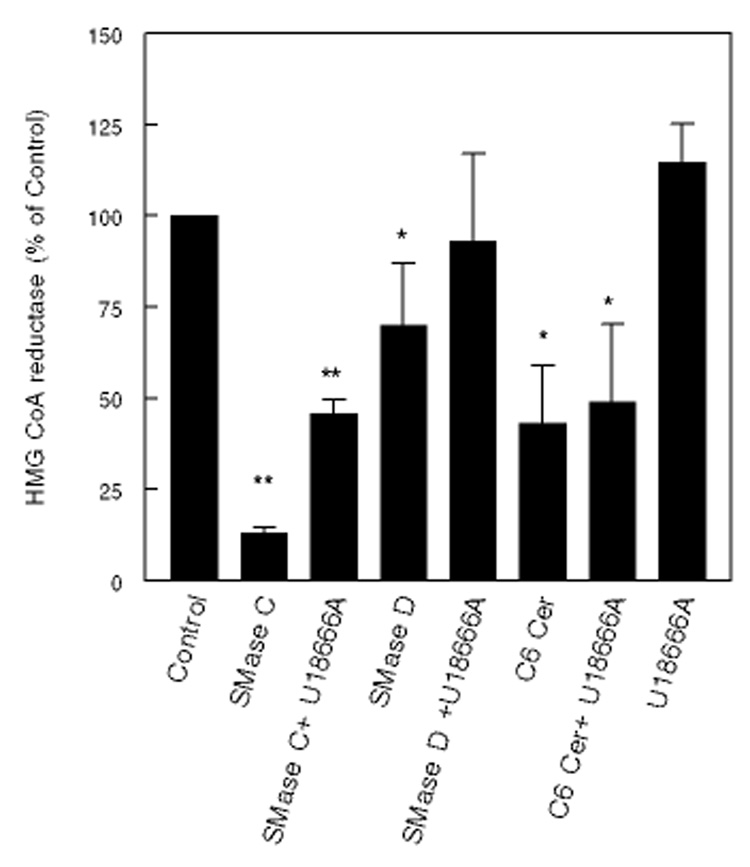

Previous studies showed that the hydrophobic amine U18666A inhibits the transport of cholesterol from the lysosomes or PM to ER [31]. If the effect of ceramide is due to a stimulation of cholesterol transport from PM to ER, U18666A should reverse this. If, on the other hand, ceramide inhibits the HMGCR activity through a mechanism not involving cholesterol transport to ER (i.e., signaling effect), U18666A should not reverse the ceramide effect, because this compound is not known to affect signaling pathways.

We first studied the effect of U18666A on cholesterol mobilization induced by SMases C and D. Since treatment with these enzymes activates ACAT and inhibits HMGCR primarily through translocation of PM cholesterol, U18666A should reverse their effects. As shown in Fig 7, 5 µM U18666A partially reversed the inhibition of HMGCR induced by SMase C and completely reversed the inhibition induced by SMase D. The inhibition of the enzyme activity by C6 ceramide, however, was not reversed by U18666A. Increasing the U18666A concentration to 50 µM did not show any further reversal of ceramide effect (results not shown). The hydrophobic amine by itself (5 µM) slightly activated the enzyme activity (+14%), presumably because of inhibition of normal cholesterol transport to ER.

Figure 7. Reversal of the effects of ceramide and SMases on HMGCR by U18666A.

Fibroblasts were treated with SMase C (0.12 U/ml), SMase D (0.2 U/ml) or C6 ceramide (50 µM) in the presence or absence of 1 µM U18666A. HMGCR activity was measured as described in the text after 2 h treatment. All activities are mean ± SEM of 3 separate experiments, and are expressed as percent of untreated control cells. * p< 0.05; ** p<0.005, compared to control.

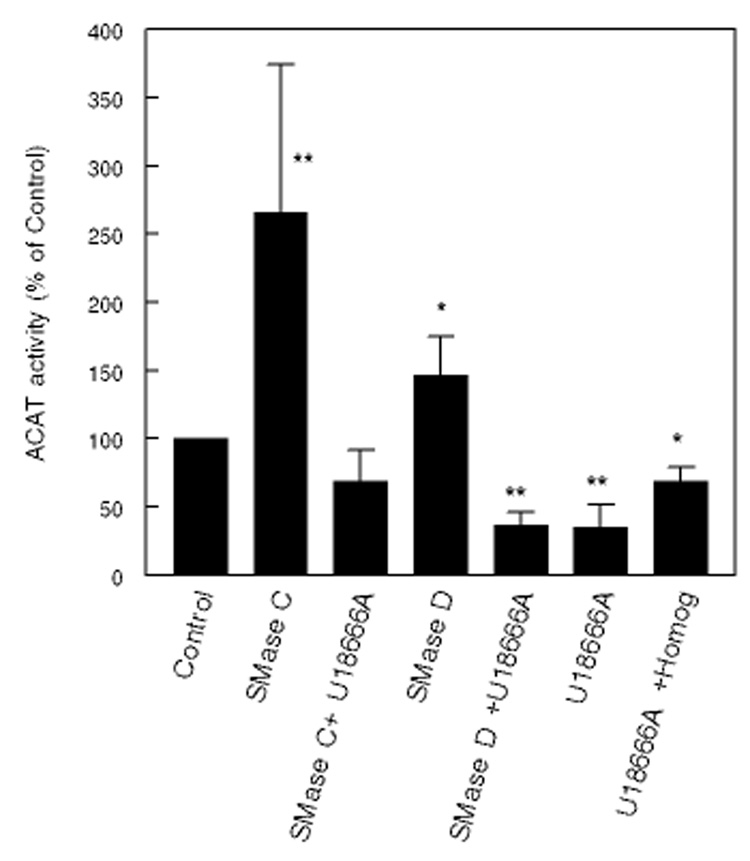

The effect of 5µM U18666A on stimulation of ACAT activity is shown in Fig 8. U18666A alone inhibited ACAT activity by about 65%, as expected from the inhibition of cholesterol transport to ER. Unlike the effect on HMG CoA reductase, it completely reversed the effects of both SMase C and SMase D on ACAT. Previous studies by Harmala et al [32] showed a complete reversal of ACAT activation, although Sparrow et al [33], using a lower concentration of U18666A, reported only a partial reversal. However, since 5 µM U18666A inhibited ACAT activity significantly even in the cell-free homogenate (−30%), the ‘reversal’ may not be entirely attributable to the inhibition of cholesterol transport.

Figure 8. Reversal of the effects of ceramide and SMases on cholesterol esterification by U18666A.

Fibroblasts were pre-labeled with 14C-cholesterol using 14C-cholesterol-HPCD complex, and then treated with SMase C (0.12 U/ml), SMase D (0.2 U/ml) or C6 ceramide in the presence or absence of 1 µM U18666A for 2h. The esterification of labeled cholesterol was then determined as described in the text. All activities are expressed as percent of activity in control (untreated) cells (mean ± SEM, n=3). * p< 0.05; ** p<0.005, compared to control.

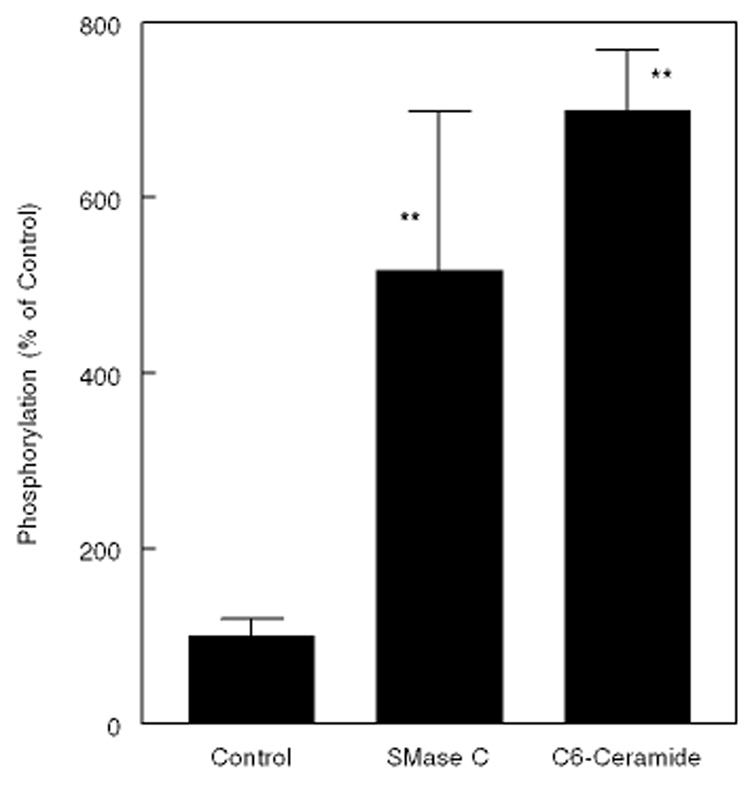

Since HMGCR is regulated by phosphorylation-dephosphorylation in addition to proteolytic degradation [10,11], we tested the possibility that ceramide affects the phosphorylation status of the enzyme. As shown in Fig. 9, treatment of the cells with SMase C resulted in a 5-fold increase in the phosphorylation of the enzyme, whereas treatment with the cell-permeable C6-ceramide resulted in a 7-fold increase. These results suggest that the ceramide generated by SMase C action has independent effect on the phosphorylation of HMGCR. Since an increase in intracellular cholesterol levels also increase the phosphorylation [10], the observed effects may be due to a combination of increased ER cholesterol, and a direct effect of ceramide on protein kinase or phosphatase reactions.

Figure 9. Effect of SMase C treatment and exogenous ceramide on phosphorylation of HMGCR.

Human skin fibroblasts were treated with SMase C (0.12 U/ml) or C6 ceramide (50µM) for 2 h in DMEM containing 32P phosphate. The microsomal proteins were immunoprecipitated using a rabbit antibody for human HMGCR, and separated on SDS gels, transferred to nitrocellulose, and determined the radioactivity in HMGCR by Phosphorimager. The radioactivity was expressed as the percent of counts present in untreated cells. The values shown are mean ± S.D of 3 experiments. ** p<0.005, compared to control (no treatment).

Discussion

It is well established that SM and cholesterol are co-localized in PM, and interact strongly with each other [1,2]. Previous studies have shown that depletion of SM by SMase C has dramatic effect on the cellular distribution of cholesterol [4,5]. The aim of the present study was to determine whether the translocation of PM cholesterol to ER in response to SMase C treatment of the cells is at least partly due to the independent effects of ceramide, rather than solely due to the loss of cholesterol-SM interaction. Although the stimulation of ACAT activity is the most common method to determine the ER enrichment of cholesterol, we could not use this method for testing the effect of exogenous ceramides because of the direct inhibition of this enzyme by ceramides even in cell- free homogenate [6,16]. In contrast, HMG CoA reductase activity was not directly inhibited by ceramide in the cell-free assay, and therefore it can be used to be used to determine the effect of exogenous ceramides on intact cells. This enzyme also responds rapidly to the changes ER cholesterol levels [17] [18].

Even though the physical interaction of SM and cholesterol in the membrane is well established [34,35], the presence of SM does not appear to be obligatory for cholesterol to remain in the plasma membrane. For example, in cells which are defective in SM synthesis, the subcellular distribution of cholesterol is not altered significantly, and the bulk of the cellular cholesterol is still present in the plasma membrane, although the raft-associated cholesterol is decreased [36]. Therefore the depletion of SM alone may not be sufficient to account for the substantial translocation of PM cholesterol to ER that occurs following SMase C treatment. Our previous studies with SMase D, which produces ceramide phosphate instead of ceramide from SM, in fact supported the hypothesis that not all of the effect on cholesterol trafficking could be explained by the loss of SM-cholesterol interaction in the PM. The data presented here show that both exogenous and endogenous ceramides inhibit HMGCR activity in intact cells, even in presence of normal amounts of SM. It is important to note that the effects of ceramide and SMase D are additive, suggesting that the depletion of SM and the generation of ceramide have independent effects on cholesterol trafficking, probably affecting different aspects of the trafficking.

Ceramide is a multi-potent cytoactive lipid with diverse effects on cells. It activates several intracellular signaling pathways involving both protein kinases and protein phosphatases [7,37]. Although its role in apoptosis has received considerable attention, its physical effects on membrane microdomain structure and function, membrane fluidity, permeability and fusion, and vesicular trafficking may be equally important. Being a ‘cone-shaped’ lipid, it promotes hexagonal phase formation, and induces membrane trafficking through vesiculation [38]. Several lines of evidence also indicate that ceramide regulates cellular cholesterol metabolism directly, as well as indirectly. Thus C2-ceramide has been reported to increase the plasma membrane content of ABCA1 transporter, which in turn results in enhanced efflux of cholesterol to apo AI particles [12]. Ceramide also selectively displaces cholesterol from the membrane rafts, possibly by competing for association with other raft lipids [13,14]. This could result in increased availability of cholesterol for transport to ER, as well as to exogenous acceptors such as apo AI and phospholipids. The sterol regulatory element (SRE)-mediated gene transcription, that controls the biosynthesis, cellular uptake and catabolism of cholesterol has also been shown to be inhibited by ceramide, independent of cellular cholesterol levels [39]. In addition, Gallardo et al [40] reported that C2 ceramide inhibits the expression of HMGCR in human U-937 and HL-60 cells, whereas it increases the expression and activity of the enzyme in HepG2 cells, apparently by inducing maturation of SRE binding protein [40]. Sphingosine, the degradation product of ceramide, has also been shown to be an inhibitor of cholesterol esterification by ACAT [41]. The present studies provide an additional mechanism by which ceramide may regulate sterol homeostasis. In addition to stimulating cholesterol transport into ER, it appears to inhibit HMGCR activity through non-sterol dependent pathways, because U18666A, which inhibits sterol transport did not completely reverse the effects of exogenous ceramide or SMase C, even at very high concentration. This is supported by our results that ceramide increase the phosphorylation of HMGCR, which is known to inactivate the enzyme [10,11]. To further investigate this aspect, we have tested the effects of some known modulators of protein phosphorylation in cells, which included H89, an inhibitor of protein kinase A [42], 6DMAP, a reported inhibitor of ceramide activated protein kinase [43], and cyclosporin A, an inhibitor of protein phosphatase 2B. However, none of these inhibitors reversed the effect of either SMase C or ceramide (results not shown). This does not, however, rule out the possibility that other kinases or phosphatases known to be affected by ceramide [7] are involved in the ceramide effect. Nevertheless, the studies presented here show that the effects of SMase C treatment on cholesterol homeostasis are not only due to the loss of SM from the PM, but also due to the generation of the bioactive ceramide molecule, which has independent effects on sterol translocation as well as on HMGCR activity.

Acknowledgements

These studies were supported by the grants from the National Institutes of Health, HL 68585, and HL 52597. We thank Dr. Yvonne Lange (Rush University, Chicago) for helpful discussions.

Abbreviations used

- ACAT

Acyl CoA: cholesterol acyltransferase

- CE

Cholesteryl ester

- D609

tricyclodecan-9-yl xanthogenate

- 6DMAP

6-dimethyl aminopurine

- DMAPP

(1S,2R)-D-erythro-2-(N-myristoylamino)-1-phenyl-1-propanol

- DTT

Dithiothreitol

- ER

Endoplasmic reticulum

- HMG CoA

Hydroxymethylglutaryl CoA

- HMGCR

HMG CoA reductase

- LPDS

Lipoprotein-deficient serum

- PM

Plasma membrane

- SM

Sphingomyelin

- U18666A

3β- (2-diethylamino ethoxy) androstenone

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Barenholz Y. Subcell.Biochem. 2004;37:167–215. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4757-5806-1_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brown DA, London E. J.Membr.Biol. 1998;164:103–114. doi: 10.1007/s002329900397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ridgway ND. Biochim.Biophys.Acta. 2000;1484:129–141. doi: 10.1016/s1388-1981(00)00006-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Slotte JP, Bierman EL. Biochem.J. 1988;250:653–658. doi: 10.1042/bj2500653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lange Y, Ye J, Rigney M, Steck T. J.Biol.Chem. 2000;275:17468–17475. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M000875200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Subbaiah PV, Billington SJ, Jost BH, Songer JG, Lange Y. J.Lipid Res. 2003;44:1574–1580. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M300103-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Perry DK, Hannun YA. Biochim.Biophys.Acta. 1998;1436:233–243. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2760(98)00145-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lange Y, Ye J, Steck TL. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;290:488–493. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.6156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mendez AJ, Oram JF, Bierman EL. J.Biol.Chem. 1991;266:10104–10111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arebalo RE, Hardgrave JE, Scallen TJ. J.Biol.Chem. 1981;256:571–574. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beg ZH, Stonik JA, Brewer HB., Jr Metabolism. 1987;36:900–917. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(87)90101-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Witting SR, Maiorano JN, Davidson WS. J.Biol.Chem. 2003;278:40121–40127. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305193200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Megha, London E. J.Biol.Chem. 2004;279:9997–10004. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309992200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yu C, Alterman M, Dobrowsky RT. J Lipid Res. 2005;46:1678–1691. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M500060-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ito J, Nagayasu Y, Ueno S, Yokoyama S. J.Biol.Chem. 2002;277:44709–44714. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208379200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ridgway ND. Biochim.Biophys.Acta. 1995;1256:39–46. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(95)00009-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lange Y, Ye J, Steck TL. Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci.U.S.A. 2004;101:11664–11667. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404766101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lange Y, Ory DS, Ye J, Lanier MH, Hsu FF, Steck TL. J.Biol.Chem. 2007;282 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M706967200. (in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brown MS, Dana SE, Goldstein JL. Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci.U.S.A. 1973;70:2162–2166. doi: 10.1073/pnas.70.7.2162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gillespie JG, Hardie DG. FEBS Letters. 1992;306:59–62. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(92)80837-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bradford MM. Anal.Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marinetti GV. J.Lipid Res. 1962;3:1–20. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bollag WB, Griner RD. Methods Mol Biol. 1998;105:89–98. doi: 10.1385/0-89603-491-7:89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nakajima M, Yamato S, Wakabayashi H, Shimada K. Biol.Pharm.Bull. 1995;18:1762–1764. doi: 10.1248/bpb.18.1762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bielawska A, Crane HM, Liotta D, Obeid LM, Hannun YA. J.Biol.Chem. 1993;268:26226–26232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Venable ME, Bielawska A, Obeid LM. J.Biol.Chem. 1996;271:24800–24805. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.40.24800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gupta AK, Rudney H. J.Lipid Res. 1991;32:125–136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bielawska A, Greenberg MS, Perry D, Jayadev S, Shayman JA, McKay C, Hannun YA. J.Biol.Chem. 1996;271:12646–12654. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.21.12646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Luberto C, Hannun YA. J.Biol.Chem. 1998;273:14550–14559. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.23.14550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ledesma MD, Brugger B, Bunning C, Wieland FT, Dotti CG. EMBO Journal. 1999;18:1761–1771. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.7.1761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liscum L, Munn NJ. Biochim.Biophys.Acta. 1999;1438:19–37. doi: 10.1016/s1388-1981(99)00043-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Harmala AS, Porn MI, Mattjus P, Slotte JP. Biochim.Biophys.Acta. 1994;1211:317–325. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(94)90156-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sparrow SM, Carter JM, Ridgway ND, Cook HW, Byers DM. Neurochem.Res. 1999;24:69–77. doi: 10.1023/a:1020932130753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Barenholz Y. Sphingomyelin-lecithin balance in membranes: Composition, structure, and function relationships. In: Shinitzky M, editor. Physiology of Membrane Fluidity. Boca Raton: CRC press; 1984. pp. 131–173. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Slotte JP. Chem.Phys.Lipids. 1999;102:13–27. doi: 10.1016/s0009-3084(99)00071-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fukasawa M, Nishijima M, Itabe H, Takano T, Hanada K. J.Biol.Chem. 2000;275:34028–34034. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005151200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ruvolo PP. Pharmacological Research. 2003;47:383–392. doi: 10.1016/s1043-6618(03)00050-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.van Blitterswijk WJ, van der Luit AH, Veldman RJ, Verheij M, Borst J. Biochem.J. 2003;369:199–211. doi: 10.1042/BJ20021528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Worgall TS, Johnson RA, Seo T, Gierens H, Deckelbaum RJ. J.Biol.Chem. 2002;277:3878–3885. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102393200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gallardo G, Lopez-Blanco F, Ruiz de Galarreta CM, Fanjul LF. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;300:397–402. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(02)02846-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Harmala AS, Porn MI, Slotte JP. Biochim.Biophys.Acta. 1993;1210:97–104. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(93)90054-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chijiwa T, Mishima A, Hagiwara M, Sano M, Hayashi K, Inoue T, Naito K, Toshioka T, Hidaka H. J.Biol.Chem. 1990;265:5267–5272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Marino MW, Dunbar JD, Wu LW, Ngaiza JR, Han HM, Guo D, Matsushita M, Nairn AC, Zhang Y, Kolesnick R, Jaffe EA, Donner DB. J.Biol.Chem. 1996;271:28624–28629. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.45.28624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]