Abstract

Objective

To identify collaborative instances and hindrances and to produce a model of collaborative practice.

Methods

A 12‐month (2005–2006) mixed methods clinical case study was carried out in a large UK ambulance trust. Collaboration was measured through direct observational ratings of communication skills, teamwork and leadership with 24 multi‐professional emergency care practitioners (ECPs), interviews with 45 ECPs and stakeholders, and an audit of 611 patients

Results

Using a generic qualitative approach, observational records and interviews showed that ECPs' numerous links with other professions were influenced by three major themes as follows. (i) The ECP role: for example, “restricted transport codes” of communication, focus on reducing admissions, frustrations about patient tasking and conflicting views about leadership and team work. (ii) Education and training: drivers for multi‐professional clinically focussed graduate level education, requirements for skill development in minor injury units (MIUs) and general practice, and the need for clinical supervision/mentorship. (iii) Cultural perspectives: a “crew room” blue collar view of inter‐professional working versus emerging professional white collar views, power and communication conflicts, and a lack of understanding of the ECPs' role. The quantitative findings are reported elsewhere.

Conclusions

The final model of collaborative practice suggests that ECPs are having an impact on patient care, but that improvements can be made. We recommend the appointment of ECP clinical leads, degree level clinically focussed multi‐professional education, communication skills training, clinical supervision and multi‐professional ECP appointments.

Keywords: emergency, ambulance, collaboration, leadership, team, communication

This paper is the second of a two‐part report which summarises the full findings of a clinical study focusing on inter‐professional collaboration in unscheduled out‐of‐hospital emergency care. Readers are encouraged to read the quantitative report1 (or the combined full report available from the lead author SC).

The context and background to this study are fully described in the quantitative report.1 In summary, recent UK initiatives have led to the development of the emergency care practitioner (ECP) role,2 defined as an “advanced practitioner (paramedic or nurse) capable of assessing, treating and discharging/referring patients at the scene”.3 Characteristics of collaborative working4 have been identified as shared decision making, partnership working, mutual dependency and power sharing.5 With the view that improved collaboration through inter‐disciplinary education may reduce medical errors6 and enhance team working in the community and emergency room,7,8 we undertook a mixed methods9 clinical case study of ECPs' collaborative practice in three regions of the Westcountry Ambulance Service NHS Trust (WAST) (UK). ECPs were trained to certificate (level 1) over 3 months or graduate level (level 3) over 2 years. We aimed to develop an overview of the current ECP role by identifying instances and hindrances to collaboration and from this to develop a model of collaboration in unscheduled care. Inter‐professional collaboration was defined as “working in a positive association with more than one professional group”. We incorporated quantitative observational approaches (measuring leadership, team work and communication ability), a patient audit1 and generic qualitative methods based upon interviews with ECPs and stakeholders.

Methods

In this mixed methods study one of our key objectives was to triangulate data from a number of sources,10 for example observational records and ratings,1 to inform the focus of interviews and to ensure that findings could be compared and contrasted. A positivist observational rating approach was supplemented by a generic qualitative approach which Caelli et al from the work of Merriam11 describe as studies that “seek to discover and understand a phenomenon, a process, or the perspectives and worldviews of the people involved”. This is a similar approach to the “interpretative description” of Thorne et al12,13 which was developed from clinicians' desire for methodological flexibility in the context of clinical objectives and settings. The credibility of a generic approach is discussed in the conclusions of this paper and three examples are listed.14,15,16

From a purposive sample, in order to include a range of perspectives (gender, profession (nurse/paramedic) and educational qualifications), 24 ECPs across the Westcounty region were interviewed (following a period of observation1). This sample was augmented by a “snowball” cascade approach, identifying stakeholder participants as the study progressed. A total of 21 stakeholders were interviewed at the end of the observational phase of the study and included, for example, senior health authority and trust managers, A&E consultants and senior nurses, paramedics, general practitioners (GPs) and practice managers, care home managers, social services and Falls group leads. Field notes were made during observations and semi‐structured 20–30‐min interviews focussed on the ECP role and collaborative experiences. Data analysis was based the three stages of analysis of Miles and Huberman.17,18 In the first data reduction and display stage, we (SC and JO) independently read and reread the transcripts (maintaining awareness of our preconceived ideas and categories). Independently, we then identified key codes and categories which were placed in context charts. Secondly, we drew conclusions by identifying category clusters and noting relationships within the data which led to the development of overarching themes and subthemes (which were discussed within the team). Thirdly, we confirmed the results by weighting the evidence and making contrasts and comparisons, before triangulating the data with other findings1 to ensure there was agreement (or at least no contradiction). Finally, at the end of the study all participants were asked to a respondent event to discuss the provisional findings and to seek new and alternative insights.19,20

Qualitative results

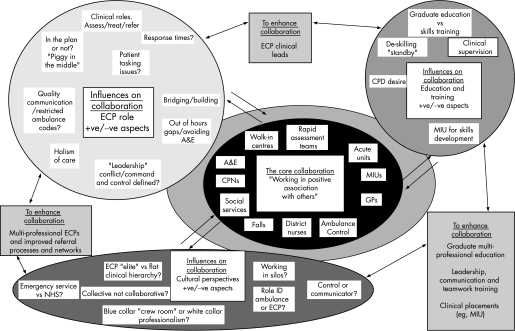

Figure 1 illustrate s the findings in a model of collaboration. Described as “influences on collaboration”, the central core describes the professional and organisational groups that ECPs contact and the outer three circles illustrate the key themes, identified by the researchers, related to the ECPs' role (cultural perspectives, education and training). All influence the “collaborative core” either positively or negatively. The three boxes that link all the circles illustrate the key predicted requirements for the enhancement of collaborative practices.

Figure 1 Influences on collaboration.

In the following section the key themes are discussed with quotations identified by participant, ECP or St (stakeholder), and by setting Int (interview) or Obs (observation).

Influences on collaboration: “injecting the core”

The core (key collaborative links)

The core objective of the ECPs' collaborative role was “being able to keep the patient in the most appropriate place…their home…or family's home…not in an A&E department” (ECP, Int). To achieve this there was considerable multi‐agency working, especially within minor injuries units (MIUs), where skills were built and maintained. Generally, associations with social services (via Call Direct) were positive, however, there appeared to be issues with Call Direct's ability to log and record calls, resulting in protracted waits on‐scene and a lack of understanding of the ECP role. In addition, the lack of out‐of‐hours services for several agencies led to the use of out‐of‐hours doctor services and possible inappropriate ED admissions.

Positive liaison with ED departments was a common theme, but cross boundary working with psychiatric services was poor. ECPs were perceived as a “transport service” and mental health services were referred to as “witches and witchcraft…psychiatric…wooh…we don't really get much training through the Ambulance Service” (ECP Int).

The GP played a key role in ECP collaboration in a variety of situations and settings. This included out‐of‐hours services as well as a GP‐led Unscheduled Treatment Service in Cullompton, Devon (CUTS). Here ECPs worked as part of a multi‐professional team, triaging, seeing and treating, and manning a “hear and treat” telephone service, with the support of other professions and “the ability to bounce off each other with clinical decisions” (ECP Int).

ECP role (positive/negative influences on collaboration)

The clinical roles of assessment, treatment and referral, holism of care and avoiding the emergency department were referred to often and clearly generate a rounded role and high degree of job satisfaction. For example, there was substantial evidence of the “see and treat process”, for example, tissue adhesive and suturing on scene. However, there were concerns about referral processes: “you can be given the run around by agencies” (ECP Int), which was particularly the case with social services (through Call Direct) where the lack of call logging systems and out‐of‐hours services, and understanding of the ECP role caused problems. But in practice many bridges were built by the “blended role” of the ECP as the “orchestrator of services” (St Int).

Based upon the transport service tradition, the team‐working culture and the use of language, we identified what we have called a “transport service” code. This “code” draws upon the notion of the “restricted communication code” originally explored by Basil Bernstein.21,22 In the ambulance service, a restricted language code was seen in the form of “crew room banter”, which in the clinical field led to implicit meaning such as “we just gel, without having to talk” (ECP Int). Unfortunately, when dealing with other professionals, this “implicit meaning” often caused collaborative failures. By contrast, those with a degree level of education appeared to be more likely to use an “elaborate code”, with a wider vocabulary and more complex syntax, especially when arranging referrals. For example, “would it be possible to arrange a definitive examination in A&E?” (Obs). However, many ECPs used both “codes” interchangeably, for example a restricted code with junior ambulance colleagues and an elaborate code for referrals to medical staff.

The ECPs demonstrated an educative role for both patients and colleagues but cited concerns about patient tasking, targets and response times, which were seen as a hindrance to the ECP role and their development: “the sooner we get rid of response times the better” (ECP Int). They expressed wishes to be free‐roaming and frustrations in negotiating with controllers/dispatchers over patient care issues, especially if this conflicted with the standard emergency service known as “the plan”. In fact, some stakeholders were forthright in their strategic concerns about the ECPs' role: “what is this new beast?” (St Int) and were concerned that targets undermine clinical decisions “time, the most valuable clinical tool, is lost” (St Int).

Leadership was an inherent role of the ECP but was not clearly expressed. In fact, at times we were left with the impression that wider collaborative teamwork may “be constrained by tribal affiliations”.23 Leadership was seen, quite rightly, as context specific with appropriate leadership emergence, but there was a notable cultural resistance to identify clinical leaders, as leadership was strongly aligned with management. We were left with the impression that respondents saw management (and leadership) as an anathema in the clinical setting – it was something they did at headquarters.

Cultural perspectives (positive/negative aspects of collaboration)

The ECPs' role was expressed as “the ability to share without prejudice or hierarchy, combined with an understanding of each others' roles” (St Int). Collaboration was hindered at times by professional jealousies within the service but was enhanced in the “flat” multi‐professional collaborative approaches at the Cullompton GP service and in MIUs.

The “them and us” battle was expressed in concerns about hierarchical “management power” over clinical autonomy, and the role of HQ Control as a “controlling” allocator of tasks or a communicator of care requirements. The conflict theme of “emergency service versus NHS” appeared to be less apparent than previously reported.24 There was minimal alignment, with other emergency services with ECPs seen as “the bridge between Acute and Primary care” (St Int). The blue collar/white collar divide remained apparent24 but in the form of “the Ambulance Service is seen as blue‐collar; the ECP, more professional” (ECP Int). It is likely that the integration of nurses into the role will have a beneficial impact on culture and collaboration, as, for example, due to their multi‐professional experience they have an ability to “squeeze out referral pathways” (ECP Int).

Role identity was another key theme with a heavy emphasis on the collective rather than the collaborative. ECPs expressed themselves as “one of the crew” (ECP Obs) and aided team morale with the use of coarse humour or the re‐counting of past “jobs”, a behaviour which appeared unprofessional when expressed in front of patients and others. The emergent practitioner role “filling the gap created by the change in GP contracts” (St Int) was very apparent, especially where ECPs worked for out‐of‐hours doctor services. But in this role concerns were raised about “misrepresentation” when ECPs appeared “out of uniform” at patients' homes in a car marked “doctor”.

Education and training (positive/negative aspects influencing collaboration)

ECPs were concerned about the level of de‐skilling while on standby and the need to up‐skill in MIUs. They also expressed a wish to learn with others in higher education to enhance collaboration “once you sit down and speak to people…you find out their problems” (ECP Int). In fact, work by Weiss and Davis25 found that nurses scored lower in their collaborative practice than more highly educated professionals and Lockhart‐Wood26 found that “nurses educated below degree level were ill‐prepared for collaborative practice and found it difficult to relate to their medical colleagues in a collegial capacity” (p 279).

Graduate education and skills training were issues of concern, for example a GP indicated “level one training is too basic” (St Int) as it focuses primarily on practical, wound‐care skills, at the expense of communication expertise needed for referrals, while others expressed the view that it was essential to employ ECPs who could see beyond the presenting complaint (St Int).

Finally, many raised concerns over the lack of clinical supervision.27 This could be developed in what we would loosely term a mentorship framework, which would ensure the safe development and supervision of trainees and fulfil ECPs' desire for continuous professional development (CPD). The format and style of supervision should be considered carefully, perhaps in a loose framework of “critical friends”, a “domain expert facilitator”,28 or through the development of “opinion leaders”.29

Discussion

It is important to consider the overall rigour of qualitative work. Caelli et al11 suggest that for a credible piece of generic qualitative research the “theoretical positioning of the researchers” should be described, especially in relation to their disciplinary affiliation and what brought them to the question. In this case the research team included members of a multi‐disciplinary team of emergency nurse academics with senior experience in the ambulance service, a business studies academic with an interest in organisational learning and a sociologist, and we were drawn to the question by our previous experience in the field.24 We came to the topic with certain assumptions, for example, in SC's case (as the clinician) the view that ECPs would be effective communicators (which was not always the case) and in JO's case (as a sociologist) that there would be marked inequalities in professional relationships (which proved not to be the case). In fact, the balance between clinician and sociologist created new views and challenged many of our preconceived ideas.

Secondly, it is important to describe the methodology and methods. The methods have been described above. We worked to the methodological guidelines described by Mertens30 and as a team we reflected on our values, biases and beliefs and made each other aware of our preconceptions. We took multiple view points from a range of professionals (n = 45) and made every attempt not to speak for our respondents and returned to them for confirmation and development of the findings. We recognised our status as researchers and therefore worked towards an adopted role of “friend or brother” to engender trust. In the observational phases of the study1 we aimed to set up a rapport while remaining as unobtrusive as possible in the clinical setting.

Thirdly, studies should demonstrate rigour,11 the contemporary approach to credibility and dependability. In this study our rigour is illustrated by our theoretical approach and the close account, or audit trail, which we have described in all aspects of the study. We were, for example conscious of the need for independent analysis of the transcripts and respondent validation.10,31 Mays and Pope10 describe the latter as “part of the process of error reduction which also generates further original data, which in turn requires interpretation”. Morse et al20 support such an approach for case study research as the context and meaning will not have been decontextualised, enabling respondents to recognise themselves and their experiences.

Finally, the analytical lens11 should be clear, in that researchers should state how they have engaged with the data. This has hopefully been made explicit throughout the reports. In the quantitative report1 we described the extrinsic quantitative influences and outputs of the ECPs' role and in this report the intrinsic cultural effects on collaborative practices. Here our engagement with the data has been based upon a pragmatic generic design, with balance from a multi‐professional research team. We have retained a “sensitivity to the ways in which the researcher and the research process have shaped the collection of data”10 and have therefore taken multiple views and confirmed findings for accurate interpretations.

In our first report1 we indicated that the study is limited by “observer effects” and a small sample size, and set in one region of the UK within one ambulance trust. For example, other trusts may have different control and response procedures. However, it is likely that most trusts in the UK have similar cultures and training programmes which this second qualitative report highlights in a rich description of culture and collaborative practice.

We have identified the significant number of professionals in the ECPs' network and the positive benefits of the ECPs' collaborative role, for example, low and focussed referral rates, developmental links in clinical areas (MIUs and CUTS), enhanced teamwork and greater fluency in patient care. But we have also identified reasons for collaborative failures, such as level of education, communication and language failings, leadership and team work ability, lack of clinical supervision, process issues between Control and responders, and cultural limitations. Staff are “ripe for change” and quickly adopt innovative concepts,32 but there remain many organisational constraints that limit collaborative practice. Finally, it is hoped that our model of collaboration (fig 1) will engender comparisons, and demonstrate good practice, requirements for change and a basis for future evaluation.4,33

Conclusions

The results from the quantitative report1 and this paper lead us to the recommendations listed in table 1. Further research is required to fully understand collaborative practices and to evaluate new and emerging roles. A comprehensive cost benefit analysis for ECPs is notably lacking; we know little about the culture of learning and influences on practice, and there is little work which addresses the potential and actual dangers inherent in the rapid development of roles in autonomous settings.

Table 1 Study recommendations for the enhancement of collaborative practices (no specific order).

| Appointment of ECP clinical leads | Lead ECPs should be appointed, ideally at consultant and masters level, to drive forward the clinical, education, supervision, networking, audit and research agenda. |

| Degree level multi‐professional education | Based upon uni‐professional and multi‐professional sessions within a modular programme34 and encompassing, for example, advanced clinical skills, leadership, mentorship, team working, cultural issues, communication and handover skills. |

| Leadership, communication and teamwork training | Short post‐registration courses such as the current DH‐funded “Developing excellence in leadership within urgent care”35 which aims to break down traditional boundaries and enhance relationship management, self‐management, the patient/client focus, political awareness, networking, leadership effectiveness measures, team resource management and situation awareness. |

| Clinical supervision/mentorship | To ensure safe practice and continuous professional development |

| Up‐skilling – clinical practice in MIUs/A&E/GP | To reduce de‐skilling (from long periods of standby) and to enhance collaboration, ECPs should be based in areas of high clinical activity, for example, MIUs, A&Es or general practice. |

| Multi‐professional appointments to the ECP role | Experienced nurses36 (and other professions) should be recruited in greater numbers to diversify the skill base, develop the culture and enhance collaborative practice. |

| Improved task allocation, referral processes and networks | Expert task allocation in HQ ambulance control and improved links with social services (Care Direct) and mental health services |

| Sharing of good practice | For example, the multi‐professional Cullompton Unscheduled Treatment Service (CUTS) |

| ECP publicity | Publicity explaining the ECP role aimed at providers and the public |

DH, Department of Health.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to offer their sincere thanks to the ambulance service and all those who participated in the study.

Abbreviations

CUTS - Cullompton Unscheduled Treatment Service

ECP - emergency care practitioner

GP - general practitioner

MIU - minor injuries unit

Footnotes

Funding: Funding was provided by the Burdett Trust for Nursing.

Competing interests: None.

References

- 1.Cooper S, O'Carroll J, Jenkin A.et al Collaborative practices in unscheduled emergency care: role and impact of the emergency care practitioner—quantitative findings. Emerg Med J 200724630–633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Joint Royal Colleges Ambulance Liaison Committee The future role and education of paramedic ambulance service personnel (emerging concepts). London: JRCALC, 2000

- 3.Department of Health Taking healthcare to the patient: transforming NHS ambulance services. London: Department of Health, 2005, 51, 64

- 4.Leathard A. Models of inter‐professional collaboration. In: Inter‐professional collaboration: from policy to practice in health and social care Hove, UK: Brunner‐Routledge, 200393–117.

- 5.D'Armour D, Ferrada‐Videla M, Rodrigiez M.et al The conceptual basis for inter‐professional collaboration; core concepts and theoretical frameworks. J Interprof Care 200519(Suppl 1)116–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Risser D, Rice M, Salisbury M.et al The potential for improved teamwork to reduce medical errors in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med 199934(3)373–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Poulton B C, West M A. Effective multidisciplinary teamwork in primary health care. J Adv Nurs 199318918–925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ummenhofer W, Amsler F, Sutter P W.et al Team performance in the emergency room: assessment of inter‐disciplinary attitudes. Resuscitation 20014939–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barbour R S. The case for combining qualitative and quantitative approaches in health services research. J Health Serv Res Policy 19994(1)39–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mays N, Pope C. Assessing quality in qualitative research. BMJ 200032050–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Caelli K, Ray L, Mill J. ‘Clear as mud'. Towards a greater clarity in generic qualitative research. Int J Qual Methods 20032(2)1–23. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thorne S, Kirkham S R, MacDonald‐Emes J. Focus on qualitative methods. Interpretative description: a noncategorical qualitative alternative for developing nursing knowledge, Res Nurs Health 199720169–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sandelowski M. Focus on research methods. Whatever happened to qualitative description? Res Nurs Health 200023334–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Manias E, Aitken R, Dunning T. Decision models used by ‘graduate nurses' managing patients' medications. J Adv Nurs 200447(3)270–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clark A M, Barbour R S, White M.et al Promoting participation in cardiac rehabilitation: patient choices and experiences. J Adv Nurs 200447(1)5–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hornsten A, Sandstrom H, Lundman B. Personal understanding of illness among people with type 2 diabetes. J Adv Nurs 200447(2)174–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miles M B, Huberman A M.Qualitative data analysis: a sourcebook of new methods. Beverley Hills, CA: Sage, 1984

- 18.Miles M B, Huberman A M.Qualitative data analysis: an expanded sourcebook. 2nd edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 1994

- 19.Bergen P L, Luckmann T.The social construction of reality. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1966

- 20.Morse J N, Barrett M, Mayan M.et al Verification strategies for establishing reliability and validity in qualitative research. Int J Qual Methods 20021(2)1–19. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bernstein B. Social class and linguistic development. A theory of social learning. In: Halsey AH, Floud JE, Anderson CA, eds, Education, economy and society. A reader in the sociology of education New York: Free Press 1961

- 22.Bernstein B.Pedagogy, symbolic control and identity: theory research critique. London: Taylor and Francis, 1996

- 23.Bleakley A. Improving patient safety through team working in operating theatres. Research seminar. Peninsula Medical School, Royal Cornwall Hospital, Treliske, Truro 2005

- 24.Cooper S, Barrett B, Black S.et al The emerging role of the emergency care practitioner. Emerg Med J 200421614–618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weiss S, Davis P. Validity and reliability of the collaborative practice scales. Nurs Res 198534299–305. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lockhart‐Wood K. Collaboration between nurses and doctors in clinical practice. Br J Nurs 20009(5)276–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Department of Health The competence and curriculum framework for the emergency care practitioner. A document for discussion. London: Department of Health, 200564

- 28.Bleakley A, Hobbs A, Boyden J.et al Safety in operating theatres: improving teamwork through team resource management. J Workplace Learn 200416(1/2)83–91. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nichols A. Using organisational learning theory as a means of mobilising knowledge resources in the control of infection. Unpublished PhD. University of Plymouth 2006

- 30.Mertens D.Research methods in education and psychology. Integrating diversity with quantitative and qualitative approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 1998352

- 31.Mays N, Pope C. Qualitative research: rigor and qualitative research. BMJ 1995311109–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Plsek P. Complexity and the adoption of innovation in healthcare. Paper presented to Accelerating Quality Improvement in Health Care: strategies to spread the diffusion of evidence‐based innovations, Washington, DC, 27–28 January, 2003

- 33.Leathard A.Inter‐professional collaboration: from policy to practice in health and social care. Hove, UK: Brunner‐Routledge, 2003

- 34.Carlisle C, Donovan T, Mercer D.Inter‐professional education. An agenda for healthcare professionals. Salisbury: Quay Books, 2005

- 35.Department of Health Developing excellence in leadership within urgent care. Tomorrow's nurse leaders today. London: Department of Health, 2005

- 36.Suserud B ‐ O. A new profession in the pre‐hospital care field – the ambulance nurse. Nurs Crit Care 2005106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]