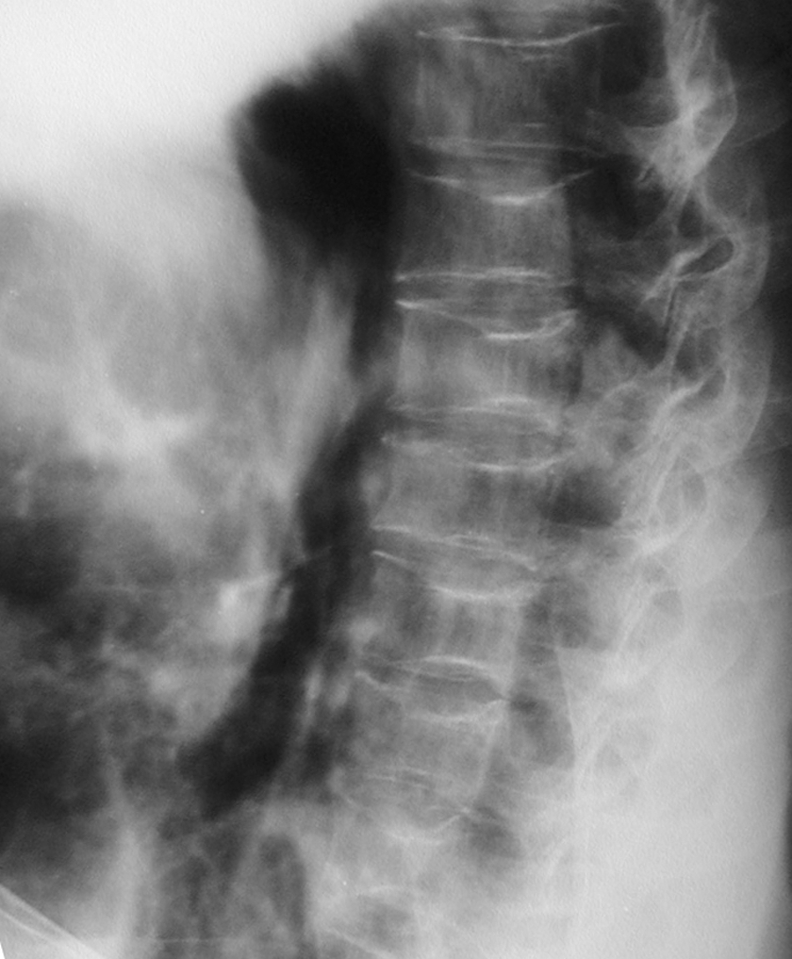

This is a case report about a radiological sign appearing in the spinal x ray of a 58‐year‐old patient with sickle cell disease (SCD), who presented at the emergency department with lumbar pain. The “fish‐vertebra” sign appears as biconcave lumbar vertebrae with bone softening in lateral and posterior–anterior radiographs of the spine as an exaggeration of the normal concavity of the superior and inferior surfaces of one or more vertebral bodies (fig 1).1 The above vertebral changes, characteristic of SCD, are the result of ischaemia (due to micro‐infarctions) of the central portion of the vertebral growth plate, with a consequent disturbance of vertebral growth.2,3

Figure 1 Thoracolumbar x ray (lateral view) of a 58‐year‐old man with sickle‐cell disease (SCD), showing the characteristic “fish‐vertebra” sign. Survival of this range is uncommon for a patient with SCD, as death in men usually occurs before the age of 48 years.

The fish‐vertebra sign is a smooth deformity of the vertebral bodies, with a characteristic biconcave body occurring as a result of squared‐off depression of the vertebral end‐plates and compression by adjacent intervertebral discs.3 SCD is a systemic hereditary disorder most commonly found in African Americans, in which fetal haemoglobin is replaced by abnormal sickle cell haemoglobin. It manifests in the second half of the first year of life. Two forms are recognised: homozygotic, HbSS (sickle cell anaemia), and heterozygotic, HbSA (sickle cell trait) or HbSC (less severe form). Vaso‐occlusive phenomena and haemolysis are the clinical hallmarks of the disease, resulting in several painful episodes (sickle cell crises) and a variety of striking organ system complications that can lead to lifelong disabilities or death.4 The radiological appearance of SCD depends on the severity and chronicity of the disease. Radiographic findings due to marrow hyperplasia include osteoporosis, “hair‐on‐end” appearance at the skull, “fish vertebra” and pathological fractures. Bone infarction causes avascular necrosis of long bones (mainly hip), epiphysial deformity and biconcave vertebrae. Infection‐related radiographic findings include septic arthritis and periostitis.5 Diagnostic radiology is not specific for vaso‐occlusive crises (VOC), and the differentiation between VOC and osteomyelitis can be a challenge. Nevertheless, VOC is much more frequent than osteomyelitis, responding rapidly to aggressive pain management, and presented in another healthy child with little or no fever.6 However, symptoms and clinical features may be identical.7 Radiographs may show bone infarcts but also signs of infection in a vascularly compromised bone.8 Although bone scans are not helpful in differentiating bone infarction from osteomyelitis, magnetic resonance imaging can be more specific.9 Differential diagnosis of the above radiological findings include thalassemia, Legg–Calvé–Perthes and Gaucher disease (table 1). However, radiological findings in thoracolumbar spine are characteristic for SCD.

Table 1 Differential diagnosis of radiological findings in sickle cell disease.

| Thalassemia | Expanded bone marrow space |

| Avascular necrosis of long bones | |

| Legg–Calvé–Perthes | Rare in African Americans |

| Idiopathic avascular necrosis of long bones | |

| Gaucher disease | Bone marrow expansion |

| Periostitis | |

| Avascular necrosis of long bones |

Advances in medical treatment have led to a prolongation of life expectancy in patients with sickle cell haemoglobinopathies. Median age at death for patients with SCD is 42 years for men and 48 years for women.10 Treatment of pain and hydration remain the main interventions in the management of sickle cell crises. Hydroxyurea has been shown to prevent VOC by increasing the amount of fetal haemoglobin. Allogeneic stem‐cell transplantation is the only curative treatment.11

In conclusion, the fish‐vertebra sign is part of the spectrum of SCD and is distinguished by the biconcavity and the bone softening of the vertebral bodies. It is mostly characteristic in SCD and can be helpful in the differential diagnosis of other conditions with similar radiological findings.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Resnick D. Hemoglobinopathies and other anemias. In: Resnick D, ed. Diagnosis of bone and joint disorders. 4th edn. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 20022147–2187.

- 2.Kooy A, de Heide L J M, ten Tije A J.et al Vertebral bone destruction in cell disease‐infection, infarction or both. Neth J Med 199648227–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Williams H J, Davies A M, Chapman S. Bone within a bone. Clin Radiol 200459132–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bunn H F. Pathogenesis and treatment of sickle cell disease. N Engl J Med 1997337762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stoller D W, Tirman P F J, Bredella M A. Sickle cell anemia. In: Stoller DW, ed. Diagnostic imaging—orthopaedics. Vol 1. Canada: Amirsys, 20047.22–7.25.

- 6.Embury S H, Vichinsky E P. Overview of the clinical manifestations of sickle cell disease. Available at http://www.uptodate.com (accessed 9 Aug 2006)

- 7.Keeley K, Buchanan G R. Acute infarction of long bones in children with sickle cell anemia. J Pediatr 1982101170–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dirschl D R, Almekinders L C. Osteomyelitis: common causes and treatment recommendations. Drugs 19934529–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moore S C, Bisset G S, Siegel M J.et al Pediatric musculoskeletal MR imaging. Radiology 1991179345–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Platt O S, Brambilla D J, Rosse W F.et al Mortality in sickle cell disease. Life expectancy and risk factors for early death. N Engl J Med 19943301639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schnog J B, Duits A J, Muskiet F A.et al Sickle cell disease; a general overview. Neth J Med 200462364–374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]