Abstract

Aim

The objective of this study is to correlate microalbumin and sialic acid levels with anthropometric variables in type 2 diabetic patients with and without nephropathy.

Methods

This study was a case control study and included 108 Trinidadian subjects (aged 15–60 years) of which 30 were healthy individuals, 38 had type 2 diabetes, and 40 were of type 2 diabetic patients with nephropathy. Blood pressure and waist to hip ratio were recorded. Fasting venous blood samples and urine samples were collected from all the subjects. Blood samples were analysed for the glucose, C-reactive protein, and sialic acid. Urine sample was analysed for microalbumin and sialic acid.

Results

Urinary microalbumin was higher among diabetic subjects (28.9 ± 30.3 mg/L) compared with controls (8.4 ± 10.2 mg/L) and was significantly higher in diabetic patients with nephropathy (792.3 ± 803.9 mg/L). Serum sialic acid was higher in subjects with diabetic nephropathy (71.5 ± 23.3 mg/dL) compared to diabetics (66.0 ± 11.7 mg/dL) and controls (55.2 ± 8.3 mg/dL). Increased microalbumin and sialic acid were correlated with other cardiovascular risk factors such as hypertension and waist to hip ratios (p < 0.05).

Conclusions

From these results it can be concluded that the increased microalbumin and sialic acid were strongly correlated with hypertension and waist to hip ratios in Trinidadian type-2 diabetic patients. Measurement of sialic acid, microalbumin, and waist to hip ratio along with the blood pressure is recommended for all type 2 diabetic patients to reduce the cardiovascular risk.

Keywords: sialic acid, microalbumin, diabetes

Introduction

Diabetes, a life long progressive disease, is the result of body’s inability to produce insulin or use insulin to its full potential, and is characterized by high circulating glucose. This disease has reached epidemic proportions and has become one of the most challenging health problems of the 21st century. It affects more than 230 million people worldwide, and this number is expected to reach 350 million by 2025. According to the World Health Organisation there were approximately 60,000 people living with diabetes in Trinidad and Tobago in the year 2000, and this number is expected to increase to 125,000 in the year 2030. The majority of these people suffer from type 2 diabetes, which is indicative of the high prevalence diabetes mellitus among Trinidadians. The disease cannot be cured but it can be controlled. The chronic hyperglycemia of diabetes is associated with significant long-term sequelae, particularly damage, dysfunction, and failure of various organs especially the kidneys, eyes, nerves, heart, and blood vessels.

Cardiovascular disease (CVD), one of the complications of diabetes mellitus has been found to be partly due to low grade of systemic inflammation (Haffner et al 2002). In the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study, there was a positive link between systemic inflammation and the development of type 2 diabetes, but this link was seen only in white non-smokers. The link was neither seen among African Americans nor among smokers (Duncan et al 2003). Low-grade systemic inflammation has been linked to and may be used to predict the onset of both type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease.

Sialic acid-rich glycoprotein is found mainly in cell membranes (Yarema 2006), and elevated levels may indicate excessive cell membrane damage, but more specifically for cells of vascular tissue. Damage to vascular tissue leads to ischemia which most affects the smallest blood vessels, particularly in the retina, kidneys, heart and brain. Sialic acid can be used as a measurement of the acute phase response because many proteins of the immune response are actually glycoproteins, and these glycoproteins have sialic acid as the terminal sugar on their oligosaccharide chain (Pickup et al 2004).

Microalbuminuria, the dominant feature of diabetic nephropathy is defined as an albumin excretion rate of 20–300 mg/24 hrs. This study was planned to determine microalbumin, and sialic acid levels in Trinidadian type 2 diabetic patients with and without nephropathy and correlate these with anthropometric variables. This information is not available for the multiethnic society that is present in Trinidad. Our earlier research demonstrated a positive correlation in the Indian population and measurement of inflammation sensitive markers may be useful to assess cardiovascular risk in diabetic patients (Nayak et al 2005). Since the Trinidadian population comprises a significant proportion of descendants of East Indian immigrants, information on a marker of cardiovascular risk among diabetics in Trinidad would allow medical practitioners to better manage their diabetic patients to prevent complications, improve life expectancy, and quality of life.

Methods

This was a case-control study comparing the concentrations of inflammatory markers and anthropometric variables in Trinidadians with and without type 2 diabetes. The study included 108 subjects (aged 15–60 years) of which 30 were healthy individuals, 38 patients had type 2 diabetes, and 40 patients had type 2 diabetes with nephropathy. The Ethics committee of the Faculty of Medical Sciences, University of the West Indies approved the study. We informed every patient of the details of the study in individual interviews, and all the provided written informed consent. All subjects were reported in the morning after an overnight fast of at least ten hours. Standing height and weight were measured. Body mass index (BMI) defined as weight in kg/height (meters) squared was used as an index of obesity. To determine waist-to-hip ratio, the standardized clinician’s tape measure was placed around the widest part of the hips and then placed around the narrowest part of the waist above the belly button and waist measurement was divided by the hip measurement. Blood pressure was measured according to the standard procedure.

Fasting blood and urine samples were collected from subjects. Serum glucose was measured by hexokinase method (Stat Fax), serum C-reactive protein and urine microalbumin were measured with a Nycocard reader (point of care instrument designed for rapid and reliable measurements of microalbumin, CRP and HbA1c).

Serum and urinary sialic acid were measured by a spectrophotometric assay (Winzler 1955). Serum (or urine) 0.15 ml was mixed with 3.60 ml of 5% TCA and the tubes were covered with marbles and kept in a boiling water bath for 15 minutes. The tubes were cooled and centrifuged for 10 minutes at 2000 g. The supernatant (1.0 ml) was mixed with 2.0 ml each of acid reagent and diphenylamine reagent. Standard and blank samples were treated in the same way. The contents were mixed using a vertex mixer, covered with marbles and placed in a boiling water bath for 30 minutes. Development of a purple color was measured on a spectrophotometer at 540 nm.

Sample specification

Trinidadian subjects between 15–60 years (mean age of 50 ± 15) comprising almost equal numbers of males and females in all groups were included. Subjects were required to be a) in good overall health with normal fasting blood glucose (controls), b) with type 2 diabetes and no complications, and c) type 2 diabetes with nephropathy. The exclusion criteria were: a) persons with type 1 diabetes, b) persons with current or recent medical condition which could affect concentrations of inflammatory markers (for instance, cancer), c) persons taking cholesterol-lowering medication, d) pregnant women, and e) heavy smokers (more than one pack of cigarettes per day).

Demographic data collected were: age, gender, and ethnicity. Potential confounding variables were diet, physical activity, and obesity.

Statistical method

Results were expressed as mean ± SD. Data were analyzed using the statistical package for social science (SPSS). The comparisons within and among group were done using one way ANOVA test. The p value < 0.05 was set as the level of significance because the distribution of most variables was not symmetric. Pearson’s correlation test was used to test correlation.

Results

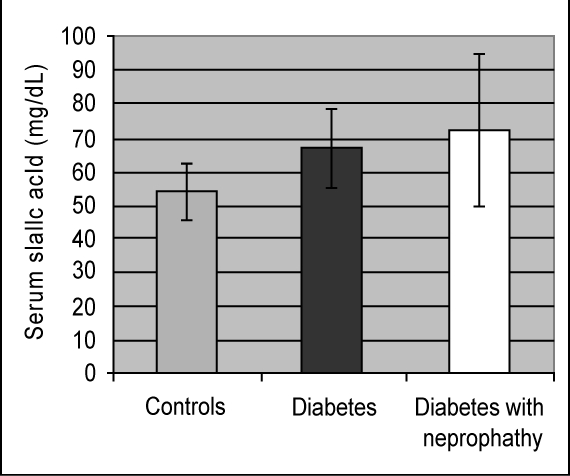

Table 1 shows the biochemical and anthropometric variables in Trinidadians with type 2 diabetes mellitus with and without nephropathy. There was a significant difference (p < 0.000) in serum sialic acid concentrations between at least two means; hence the null hypothesis is rejected. Serum sialic acid concentrations were significantly higher among the diabetic subjects (67.0 ± 11.7 mg/dL) as compared to the controls (54.2 ± 8.3 dL) (p < 0.01) (Figure 1). Increased serum sialic acid was found among diabetics with nephropathy (72.5 ± 22.3 mg/dL) as compared with the controls (p < 0.000) (Figure 1). Urinary microalbumin in diabetic nephropathy patients was significantly higher 792.3 ± 803.9 mg/L) compared with diabetics (28.9 ± 30.3) and healthy individuals (8.4 ± 10.2 mg/L).

Table 1.

Biochemical and anthropometric variables in the controls, diabetics, and diabetics without nephropathy

| Variable | Controls (Mean ± SD) n = 30 |

Diabetics (Mean ± SD) n = 38 |

Diabetes with nephropathy (Mean ± SD) n = 40 |

|---|---|---|---|

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27.9 ± 7.3 | 29.2 ± 9.5 | 27.1 ± 6.1 |

| Waist-to-hip ratio | 0.86 ± 0.06 | 0.98 ± 0.07* | 0.99 ± 0.06* |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 123.9 ± 14.6 | 145.4 ± 22.5* | 162.3 ± 26.0* |

| Serum sialic acid (mg/dL) | 54.2 ± 8.3 | 67.0 ± 11.7* | 72.5 ± 22.3* |

| Urine sialic acid (mg/dL) | 29.1 ± 15.2 | 38.6 ± 28.5 | 36.0 ± 38.9 |

| Microalbumin (mg/L) | 8.4 ± 10.2 | 28.9 ± 30.3 | 792.3 ± 803.9 |

| C-reactive protein (mg/L) | 2.0 ± 2.1 | 3.2 ± 4.2 | 3.4 ± 6.4 |

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 88.8 ± 9.8 | 135.6 ± 44.3* | 154.9 ± 74.9* |

Notes: p < 0.05, significant compared with controls.

Figure 1.

Mean sialic acid concentrations in three study groups.

The waist-to-hip ratios of the diabetics (0.98 ± 0.07) and nephropathic diabetics subjects (0.99 ± 0.06) were significantly higher than the controls (0.86 ± 0.06) (p < 0.000). Systolic blood pressure was significantly higher in diabetics (145.4 ± 22.5 mmHg) and diabetic nephropathy (162.3 ± 26.0 mmHg) subjects when compared with the controls (123.9 ± 14.6 mmHg) (p < 0.000).

Fasting blood glucose was significantly high among diabetics (p < 0.05). There was no significant change in the concentrations of C-reactive protein and BMI between the three study groups. Serum sialic acid was significantly correlated with urine albumin (p < 0.01), waist-to-hip ratio (p < 0.05) and systolic blood pressure (p < 0.01). This study demonstrated good correlation between serum sialic acid and the other anthropometric variables.

Discussion

This study found sialic acid can be used as a potential inflammatory marker for diabetes mellitus (Crook et al 2001). Previous reports have also indicated that elevated serum sialic acid (SSA) concentrations were associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease and microvascular diabetes related complications (Lindberg et al 1991). Our study primarily focuses on the relationship between inflammatory markers and anthropometric variables. Earlier studies have indicated that SSA concentrations are elevated in diabetics (both type 1 and type 2) with and without nephropathy, while others have reported no such correlation (Abdella et al 2000; Crooket al 2002). Studies have also found that the presence or absence of this trend may be related to ethnicity (Lindberg et al 1997). Our findings indicate a significant increase in SSA concentrations in diabetic patients in comparison to controls even for patients with diabetic nephropathy.

Differences between SSA concentrations and controls were more significant (p < 0.000) for those with diabetic nephropathy than for diabetics without nephropathy (p < 0.010). Serum sialic acid is generally bound to acute phase proteins (Melajarvi et al 1996) and possible explanations for the increase in SSA concentrations have been put forward. Research studies have shown that the concentration of sialic acid in serum is elevated in pathological states when there is tissue damage, tissue proliferation and inflammation. Studies have also indicated that vascular permeability is regulated by sialic acid moieties. The vascular endothelium carries a high concentration of sialic acid and hence extensive microvascular damage associated with non-insulin dependant diabetes mellitus (NIDDM), could account for its shedding into the circulation leading to an increase in vascular permeability and overall increased SSA concentrations (Crook et al 2001). Tissue injury caused by diabetic vascular complications stimulates local cytokine secretion from cellular infiltrates such as macrophages and endothelial cells. This induces an acute phase response with release of acute phase glycoproteins with sialic acid from the liver into the general circulation again leading to increased SSA concentrations (Crook et al 2001). Another plausible explanation for the increased SSA is that there may be a difference in the ratio between the two forms of erythrocyte sialidases which are important in maintaining the viability of the erythrocyte and its survival in the circulating blood (Traving et al 1998).

The increase in urine albumin in the diabetics compared with the controls can be interpreted as an early sign of nephropathic changes in those individuals. Increase in urine albumin seen with diabetic nephropathy can be attributed to degradation of the glomerular basement membranes and hypertension, both characteristic of diabetic nephropathy (Phillip et al 2006). The presence of microalbuminuria is a marker of endothelial dysfunction whether or not it is progressive, and indices an increased risk of generalized atherosclerosis and increased mortality from cardiovascular disease (English et al 2001).

The positive correlation between urine albumin levels and serum sialic acid was seen in earlier studies (Chen et al 1996). The actual cause of this occurrence is not known; however, several researchers have proposed a variety of mechanisms. One such mechanism includes the shedding of sialic acid into the circulation as a result of vascular endothelial damage. Vascular damage is seen throughout the body including the kidneys especially in diabetic nephropathy. Consequently, there is increased filtration of albumin via the damaged glomeruli and hence an increased albumin loss in the urine (Yokayama et al 1996). Blood pressure and microalbuminuria are also risk factors for cardiovascular disease. Therefore it can be concluded that sialic acid may be considered as a possible marker for cardiovascular disease. Previous studies also showed showed a positive association between SSA and systolic blood pressure and urine albumin excretion (Crook et al 1993, 1994).

We found a positive correlation between waist to hip ratio and SSA, but not with BMI. This indicates that central adiposity may be an important marker of NIDDM as opposed to general obesity since waist to hip ratio is a specific indicator of central adiposity (Favier et al 2005). Central adiposity being a cardiovascular risk factor, these patients may have underlying microvascular complications which may explain the correlation observed with SSA (Welborn et al 2003). Researchers also showed that sialic acid but not CRP, is significantly associated with one or the other features of metabolic syndrome, independent of BMI (Browning et al 2004), further supporting the use of SSA as a marker for cardiovascular risk. The insignificant increase in the CRP levels among the three groups could be explained by the inherent inflammatory state in diabetics with and without complications (Raz et al 2003). There was also no correlation between sialic acid and CRP suggesting that these inflammatory markers occur independent of each other.

We conclude that the increased serum sialic acid concentration and microalbumin in diabetics with and without nephropathy positively correlates with systolic blood pressure and waist-to-hip ratio. These findings suggest the use of microalbumin, serum sialic acid and waist to hip ratio along with blood pressure measurement to protect the diabetic patients from developing cardiovascular complications. Such investigations can not only improve the quality of life but also reduce mortality in diabetic patients in Trinidad.

Acknowledgments

School of Graduate studies, the University of the West Indies, Trinidad supported this study. We sincerely thank Prof Lexley M Pinto Pereira for editing this article. Authors are thankful to Dr Iqbal Akhbar, Nurse Henry and Ms. Serrete of the St Joseph Health Centre; Dr Lesley Roberts and Nurse Roberts of the Mt Hope Nephrology Clinic and Drs Jaghroo and Hasranah, as well as the nursing staff of the Sangre Grande Hospital for their support throughout our study. We also wish to thank Ms Debbie Hillaire, Mr Vernie Ramkissoon and all of the Lab Technicians at the Biochemistry unit of the Faculty of Medical Sciences, UWI, St Augustine for their assistance. We are also indebted to all those who participated in our study.

References

- Abdella N, Akanji A, Mojiminiyi O, et al. Relationship of serum total sialic acid concentrations with diabetic complications and cardiovascular risk factors in Kuwaiti Type 2 diabetics. Diabetes Research and Clinical Practic. 2000;50:65–72. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8227(00)00144-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browning LM, Jebb SA, Mishra GD, et al. Elevated sialic acid, but not CRP, predicts features of the metabolic syndrome independently of BMI in women. Int J Obes Relat. 2004;28:1004–10. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crook MA, Pickup JC, Lumb PJ, et al. Relationship between plasma sialic acid concentration and microvascular and macrovascular complications in type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2001;24:316–22. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.2.316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crook MA, Goldsmith L, Ameerally P, et al. Serum sialic acid, a possible cardiovascular risk factor is not increased in Fijian Melanesians with impaired glucose tolerance or impaired fasting glucose. Ann Clin Biochem. 2002;39:606–8. doi: 10.1177/000456320203900611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Gall M, Yokoyama H, et al. Raised serum silaic acid in NIDDM patients with and without diabetic nephropathy. Diabetes Care. 1996;19:130–34. doi: 10.2337/diacare.19.2.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crook M, Earle, Morocutti A, et al. Serum sialic acid a risk factor for cardiovascular disease is increased in IDDM patients with microalbuminuria and clinical proteinuria. Diabetes Care. 1994;17:305–10. doi: 10.2337/diacare.17.4.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crook M, Tutt P, Pickup JC. Elevated serum sialic acid concentrations in NIDDM and its relationship to blood pressure and retinopathy. Diabetes Care. 1993;16:57–60. doi: 10.2337/diacare.16.1.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan BB, Schmidt M, Pankow JS, et al. Low grade systemic inflammation and the development of type 2 diabetes: the atherosclerosis risk in communities study. ADA. 2003;52:1799–805. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.7.1799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- English P, Williams G. Type 2 diabetes. London, Martin Dunitz Ltd. AnnNY Acad Sci. 2001;1067:448–53. [Google Scholar]

- Favier F, Jaussent I, Moullec N, et al. Prevalence of Type 2 diabetes and central adiposity in La Reunion Island. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2005;22:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2004.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haffner S, Greenberg A, Weston W, et al. Effect of Rosiglitazone treatment on non-traditional markers of cardiovascular disease in patients with type 2 diabetes. AHA. 2002;106:679–84. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000025403.20953.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindberg G, Eklund GA, Gullberg B, et al. Serum sialic acid concentration and cardiovascular mortality. Br Med J. 1991;302:143–46. doi: 10.1136/bmj.302.6769.143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindberg G, Iso H, Rastum L, et al. serum sialic acid and its correlate in community samples from Akita, Japan and Minneapolis, USA. Int J Epidemiol. 1997;26:58–63. doi: 10.1093/ije/26.1.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melajarvi N, Gylling H, Miettinen T. Sialic acids and the metabolism of low density lipoprotein. J Lipid Res. 1996;37:1625–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nayak S, Bhaktha G. Relationship between sialic acid and metabolic variables in Indian type 2 diabetic patients. Lipid Health Dis. 2005;4:15–19. doi: 10.1186/1476-511X-4-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickup JC. Inflammation and activated innate immunity in the pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:813–23. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.3.813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raz I, Sharfrir ES. Diabetes: from research to diagnosis and treatment”. Taylor and Francis Ltd; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Traving C, Schaver R. Structure and function and metabolism of diabetic control and complications. Cell Mol Life Sci. 1998;54:1330–49. doi: 10.1007/s000180050258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillip MH. Prevention of progression in diabetic nephropathy. Diabetes Spectrum. 2006;19:18–24. [Google Scholar]

- Winzler RT. Determination of serum glycoproteins. In: Glick DT, editor. Methods of Biochemical analysis. II. New York: Interscience Publishers, Inc; 1955. p. 298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welborn TA, Dhaliwal SS, Bennett SA. Waist – hip ratio is the dominant risk factor predicting cardiovascular death in Australia. Med J Aus. 2003;179:580–85. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2003.tb05704.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yarema K. The sialic acid pathway in human cells. Baltimore: John Hopkins University; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Yokoyama H, Jensen J, Myrup B, et al. Raised serum sialic acid concentration precedes onset of microalbuminuria in IDDM. Diabetes Care. 1996;19:435–40. doi: 10.2337/diacare.19.5.435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]