ABSTRACT

OBJECTIVE

To understand the development of culturally based and community-based alcohol and substance abuse treatment programs for aboriginal patients in an international context.

SOURCES OF INFORMATION

MEDLINE, HealthSTAR, and PsycINFO databases and government documents were searched from 1975 to 2007. MeSH headings included the following: Indians, North American, Pacific ancestry group, aboriginal, substance-related disorders, alcoholism, addictive behaviour, community health service, and indigenous health. The search produced 150 articles, 34 of which were relevant; most of the literature comprised opinion pieces and program descriptions (level III evidence).

MAIN MESSAGE

Substance abuse in some aboriginal communities is a complex problem requiring culturally appropriate, multidimensional approaches. One promising perspective supports community-based programs or community mobile treatment. These programs ideally cover prevention, harm reduction, treatment, and aftercare. They often eliminate the need for people to leave their remote communities. They become focuses of community development, as the communities become the treatment facilities. Success requires solutions developed within communities, strong community interest and engagement, leadership, and sustainable funding.

CONCLUSION

Community-based addictions programs are appropriate alternatives to treatment at distant residential addictions facilities. The key components of success appear to be strong leadership in this area; strong community-member engagement; funding for programming and organizing; and the ability to develop infrastructure for long-term program sustainability. Programs require increased documentation of their inroads in this developing field.

RÉSUMÉ

OBJECTIF

Comprendre l’élaboration des programmes de traitement de l’alcoolisme et de la toxicomanie adaptés à la culture et aux collectivités autochtone, dans un contexte international.

SOURCES DE L’INFORMATION

On a consulté les bases de données HealthSTAR et PsycINFO et des documents gouvernementaux entre 1975 et 2007, utilisant les rubriques MeSH Indians, North American, Pacific ancestry group, aborigenal, substance-related disorders, alcoholism, addictive behaviour, community health service, et indigenous health. Sur 150 articles repérés, 34 étaient pertinents; la plupart rapportaient des opinions fragmentaires et des descriptions de programme (preuves de niveau III).

PRINCIPAL MESSAGE

Dans certaines collectivités autochtones, l’alcoolisme et la toxicomanie sont des problèmes complexes requérant une approche multidisciplinaire adaptée à la culture. Les programmes en milieu communautaire ou par des unités de traitement mobiles semblent une avenue prometteuse. Idéalement, ces programmes incluent prévention, réduction des dommages, traitement et suivi. Souvent, les sujets n’ont pas à quitter leur collectivité. Le programme devient un facteur de développement puisque la collectivité en devient responsable. Sa réussite exige des solutions élaborées dans la collectivité, beaucoup d’engagement et d’intérêt de la part de la collectivité, du leadership et un financement soutenu.

CONCLUSION

Les programmes communautaires contre la dépendance sont des solutions de rechange appropriées aux traitements dans les établissements éloignés de soins aux toxicomanes. Les facteurs clés du succès semblent être un leadership local fort; un engagement solide des membres de la collectivité; un financement pour la programmation et l’organisation; et l’établissement d’une infrastructure permettant la survie à long terme du programme. Les programmes auront besoin de plus de documentation sur cette incursion dans un nouveau domaine.

Aboriginal communities have identified alcohol and substance abuse as serious concerns.1 A total of 74% of on-reserve participants in a 2003 First Nations survey (N = 1606) thought that alcohol and illegal drugs were dangerous to health and rated them as their biggest health concerns.1

In 1991, the Aboriginal Peoples Survey (N = 25 122) noted 86% of communities rated alcohol abuse as a serious problem.2 These concerns about the pervasiveness of addictions are unchanging: the 2003 First Nations Regional Longitudinal Health Survey of 279 aboriginal communities in Canada implicated alcohol in 80% of suicide attempts and 60% of violent episodes.3

While most aboriginal people do not exhibit alcohol-related problems4 and the rate of abstainers in First Nations communities is twice the Canadian rate,3 some communities are disabled by problems with alcohol.

Currently the model of alcohol and substance abuse care in many remote aboriginal communities consists of referral to residential treatment centres for 3- to 6-week programs. These centres usually exist far from individuals’ home communities. Individuals return from treatment to the same situations and stressors with little or no aftercare5-8; relapse rates are 35% to 85%, most within 90 days.7

A community-based approach to prevention, treatment, and aftercare programs attempts to address these environmental factors by extending healing to the community level. Cultural relevance in addictions treatment can vary from adding an aboriginal component to the disease model of Alcoholics Anonymous to developing community-based participatory programs with a sociocultural-spiritual model.9-12 Community-based treatment emphasizes prevention, treatment, and after-care taking place in one’s home community.

The principal author (A.J.) is a family physician and addictions worker for a First Nations community in northwestern Ontario and is collaborating with the Chief and community leaders to help facilitate the successful creation of community-driven programming.

Data sources

A search was undertaken to identify literature on community-based substance abuse services for aboriginal communities in an international context. MEDLINE, HealthSTAR, and PsycINFO databases were searched with the following MeSH terms and key words: American Native continental ancestry group; Indians, North American; Oceanic Ancestry Group; Inuit; Native; Native American; Native Canadian; American Indian; aboriginal; First Nations; behaviour, addictive; addiction; substance abuse; substance; alcohol; opioid; narcotic; illicit drugs; substance-related disorders; alcohol-related disorders; alcohol-induced disorders; alcoholic intoxication; alcoholism; amphetamine-related disorders; cocaine-related disorders; marijuana abuse; opioid-related disorders; heroine dependence; morphine dependence; phencyclidine abuse; psychoses, substance abuse; substance abuse, intravenous; community; community health services; community mental health services; counseling; indigenous, health services; counsel; therapy; and treatment. The results were manually limited to English papers published between January 1975 and June 2007. Government documents were also reviewed.

Study selection

We reviewed the full texts and abstracts of 150 articles to isolate those 34 articles relating to alcohol and drug addictions programs for aboriginal communities (Table 11-3,5-35). We excluded articles on nonaddiction mental health services, tobacco, gambling, prevalence studies, and health sequelae of drug use (HIV, hepatitis C) in order to maintain a focus on alcohol and substance abuse.

Table 1.

Review of studies and articles on culturally based and community-based aboriginal alcohol and substance abuse treatment programs

| STUDY OR ARTICLE | LEVEL OF EVIDENCE | N | TYPE OF STUDY OR ARTI CLE | FINDINGS OR COMMENTS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fisher et al,13 1996 | II | 791 | Quantitative: measured retention rates | Inclusion of traditional Native activities increased retention rates in Native and non-Native clients |

| Boyd-Ball,14 2003 | II | 63 | Quantitative: interviews and observation | Family-enhanced intervention decreased alcohol consumption |

| Scott and Myers,15 1988 | II | 76 | Quantitative: assessment of fitness, self- evaluation, and substance use | Increased self-efficacy after fitness training; relationship noted between low self-enhancement and substance use |

| Kahn and Fua,16 1992 | II | 145 | Quantitative: program completion and postprogram employment | Increased rate of employment after program; number of aboriginals treated increased with aboriginal treatment providers |

| Ellis,17 2003 | II | 50 000 | Quantitative | Mentoring effort between 2 communities to develop policies and initiatives led to a 150% decrease in motor vehicle collisions in the mentored community |

| Franks,18 1989 | II | 54 | Quantitative | Patrols by community members and community involvement in intervention and setting norms for acceptable behaviour decreased no. of solvent sniffers from 54 to 1 |

| Mohatt et al,12 2004 | II | 152 | Qualitative: interviews | Deeper level of inquiry when community members involved in the development of research process |

| Robinson et al,9 2006 | II | 31 | Qualitative: interviews | Treatment staff found holistic family and community approaches to be more effective than individual approaches |

| Noe et al,19 2003 | II | 8 communities | Qualitative: program description and assessment | Community programs improved community interest, engagement, capacity, and organizations’ policies for addressing substance abuse and infrastructure |

| Chong and Herman- Stahl,5 2003 | II | 30 | Mixed methods: interviews | Substantial reduction in frequency of drinking following 6 mo of telephone aftercare |

| Parker et al,20 1991 | II | 34 | Mixed methods: interviews and self-report | Correlation between cultural activities and decreased substance use rates |

| Flores,10 1985 | II | 73 | Survey | Difference in values between non-Natives and Natives |

| Ekos Research Associates,1 2004 | II | 1606 | Survey | 84% of on-reserve youth perceived alcohol to be dangerous |

| Aboriginal Peoples Survey,2 1993 | II | 25 122 | Survey | 86% of communities rated alcohol abuse as a serious problem |

| First Nations Regional Health Survey,3 2003 | II | 270 communities | Survey | Alcohol abstinence and heavy drinking higher in the First Nations population than the general Canadian population |

| Wiebe and Huebert,6 1996 | III | NA | Description of treatment model | Community involvement and mobilization develops intervention appropriate to community |

| Chamberlin,8 1991 | III | NA | Program description | Rates of sobriety in CMT higher than traditional off- reserve treatment |

| Smye and Mussell,21 2001 | III | NA | Discussion of programs | Community-based and culturally based programs use holistic approaches: spiritual, community components |

| Mills,22 2003 | III | NA | Program description | Including traditional activities in treatment increases cultural identity and validates Native culture |

| Hitchen,23 2001 | III | NA | Program description | Employment correlated with sobriety; 800% increased employment with vocational rehabilitation aftercare program |

| Edwards et al,24 2000 | III | NA | Discussion of model | Community readiness model is used to assess and respond to community needs |

| Alberta Alcohol and Drug Abuse Commission,25 1989 | III | NA | Handbook for CMT model | CMT model is community based and community driven; it should be flexible to respond to each community |

| Coates,26 1991 | III | NA | Program description | Community-based day programs are cost effective and accessible |

| Saskatchewan Alcohol and Drug Abuse Commission,27 1989 | III | NA | Handbook for CMT model | CMT is a cost-effective alternative to residential treatment; community involvement and support in treatment and aftercare creates a supportive substance- free environment |

| Abbott,28 1998 | III | NA | Literature and program review | No RCTs; differences between worker and client belief systems; community healing involves entire community |

| Gray et al,29 1995 | III | NA | Literature and program review | Evaluation requires community involvement, flexible techniques, cultural appropriateness, and inclusion of descriptive qualitative methods |

| Health Canada,7 1998 | III | NA | Literature review | Contemporary programs emphasize community involvement to achieve community well-being |

| May,30 1986 | III | NA | Literature review | Creative solutions are required to reduce harm, increase knowledge, and improve rehabilitation |

| Gray et al,31 2000 | III | NA | Literature review | Culturally appropriate models should use an array of techniques for comprehensive program evaluation |

| Novins et al,32 2000 | III | NA | Review | Addictions services need improved rates of service utilization and locally relevant programming; increased research efforts are essential for improving services |

| Beauvais,11 1992 | III | NA | Opinion piece | Substance abuse requires local solutions and grassroots community involvement |

| May,33 1992 | III | NA | Opinion piece | Broad-based community action and comprehensive policies based on local, community-specific data are required to change norms of values of communities |

| Thurman et al,34 2003 | III | NA | Opinion piece | Community readiness model assesses stages of readiness to develop community-driven models; requires community partnerships and draws on strengths of the community |

| Mail,35 1992 | III | NA | Opinion piece | Solutions should be community driven; increased cross- cultural training and sensitivity is required for nonaborigi- nal treatment staff |

CMT— community mobile treatment, NA—not applicable, RCT—randomized controlled trials.

Four aboriginal population surveys were included, as well as 19 opinion, review, and program description articles. Six quantitative, 3 qualitative, and 2 mixed-methods studies were identified. The largest number of articles was from the United States, followed by Canada, Australia, and New Zealand.

Synthesis

The literature on community-based addictions programs emphasizes the importance of viewing drug and alcohol addictions through a sociocultural lens. The models attempt to address the problem at the community level through grassroots efforts to enhance community empowerment and mobilization. Community and individual well-being is associated with positive prevention, treatment, and aftercare outcomes. Some authors see community engagement and development, rather than changes to drug and alcohol consumption rates exclusively, as the objectives of their models.19

Aboriginal concepts of health and healing

Concepts of health—based on the aboriginal medicine wheel—view physical, emotional, mental, and spiritual aspects as interrelated.9,21 Several programs incorporate traditional practices and activities into prevention and treatment.13,14,22,36 The Selkirk Healing Centre, located in Manitoba, addresses the spiritual and cultural component of health by employing elders as cultural leaders. This has led to a reduction in substance abuse and increased self-reliance.36

Boyd-Ball studied the Shadow Project (N = 63), an 8-week residential program offering culturally relevant, enhanced family interventions through individual and group therapy. The project saw a reduction in alcohol use in the group that received family-enhanced therapy compared with the control group, but no substantial differences in drug use. To sustain the treatment results, the author recommends culturally appropriate care that recognizes historical trauma.14

Prevention education

Cultural relevance is important in educational programs. Early approaches to prevention often included educational models predicated on the belief that people informed of the risks of their behaviour would choose not to participate in activities with known risks.31 Parker and colleagues’ interviews of American Native* youth (N = 34) found that many of the participants who had experienced school drug-education programs unfortunately described them as an imposition of someone else’s perspective and decisions.20

Scott and Myers discuss the correlation between negative self-concept and increased substance abuse. In their 1988 quantitative study (N = 76) they found an increase in self-enhancement following completion of a fitness training program for First Nations teenagers from the River Desert Community in Quebec. Drug and alcohol use increased in the control group, but remained constant in the treatment group.15 Studies have examined the role of vocational training as a means of decreasing substance abuse rates.16,19,23 One program created internships for the community’s youth in various professions and industries. Unfortunately, no evaluation was reported.19

Parker and colleagues, in their quantitative study of a self-identity–enhancing approach to preventing substance abuse, stressed the importance of self-concept through cultural affiliation. Through surveys and self-reported data (N = 34), they found that engaging off-reserve aboriginal youth (aged 14 to 19) in cultural activities yielded lower rates of drug and alcohol use compared with the control group, who had not participated in cultural activities.20 The program also included a peer-mentoring component, in which older children acted as peer assistants. Results of the study showed a negative correlation between cultural affiliation and substance abuse.

Prevention policy and harm reduction

Substance abuse can lead to adverse events in all cultures. The consequences of substance abuse in American aboriginal communities have been documented for motor vehicle collisions (odds ratio [OR] 2.5-5.5), cirrhosis (OR 2.6-3.5), suicide (OR 1-2), and homicide (OR 1.7-2.3).30 Various harm-reduction strategies have been suggested and implemented in a variety of communities. In his 1986 review of addiction prevention programs, May discussed strategies to reduce vehicle collisions, such as new legislation and enforcement, road engineering, and public education, as means of reducing harm.30 Other strategies suggested include the following: sobering-up shelters, which provide a dignified alternative to placing intoxicated people in police custody, and night patrols and personal injury prevention initiatives.30 The successful outcome following harm-reduction initiatives in Fremont County in Wyoming highlights the potential for policies such as local alcohol excise taxes, alcohol server training, Sunday alcohol sales bans, and closing troublesome bars.17 These types of policies in the county led to a reduction in motor vehicle collisions and a reduction in mortalities from both suicide and homicide.17

While supply reduction saw positive results in Fremont County, other studies argue for increasing accessibility to alcohol vendors in order to prevent other types of solvent abuse.33 In his 1992 review of alcohol policies in Native communities in the United States, May emphasized the importance of community involvement in choosing policies that would best fit the community and address each kind of alcohol-related harm.33

Community healing

Community mobile treatment

Treating the whole community honours the holistic approach of the inter-relatedness of individuals and their communities. The community mobile treatment (CMT) model, developed in 1984, views substance abuse as “a local problem that requires community-based solutions.”6 Wiebe and Huebert documented the development of a mobile team of addictions workers in Prince George, BC, who were invited to several regional aboriginal communities with dire rates of alcoholism as high as 90%.6 The goal of CMT is to mobilize the community in order to heal the group as a whole.6,24,25 Changes in values and social structures require a cohesive understanding of what is deemed acceptable behaviour in the sociocultural belief system of the community.6,8,28 The program requires that a community first identify a need for intervention as well as a belief that change is possible. Historically this process takes 1 to 2 years, in which time much community mobilization work is done to promote a culture of sobriety and support for recovering individuals. This time period is then followed by 21 to 28 days of CMT and aftercare programming.6

In the communities that underwent CMT, as many as 75% of the community members received substance abuse treatment. A survey conducted 6 months after treatment in the community of Anahim Lake, BC, reported a 75% abstinence rate.6 Similar interventions in Saskatchewan and Alberta have had promising results.8,25-27 These programs depend on community vol-unteerism and engagement using various initiatives and require strong local leadership.

Community readiness

The community readiness strategy, which also takes a community empowerment approach, is predicated on the belief that communities are at different stages of readiness for intervention.24,34 By measuring these stages, different types of intervention can be identified to best suit communities’ needs.24,34 Thurman and colleagues described the strengths of the model, referring to Alaskan villages that used the model to address the problem of suicide.34

Other community interventions

The Round Lake Treatment Centre in British Columbia combines community-based treatment with inpatient services. The program emphasizes cultural awareness through healing circles and family involvement. Evaluation of results from 1991 to 1995 indicated that most participants were “clean and sober” 2 years after completing the program. Objectives of the study also considered outcomes such as improved family relations, improved quality of life, and improved self-image.7

Franks’ study on petrol-sniffing interventions in an Australian aboriginal community illustrated the effectiveness of engaging community members in setting community norms based on acceptable behaviour, as well as involving community members in enforcing the norms. Patrols for petrol-sniffing youth were performed by community members, and the youth were assigned to families who cared for and supported them. From 1982 to 1984 the number of petrol sniffers was substantially reduced. The remaining resistant sniffers and their families received intensive counseling and respite stays in another community or outstation.18

The emphasis on partnerships and the integration of prevention and treatment into existing community programs is common in the literature.24,35 Authors suggest involving schools, community organizations, band councils, social services, and churches in the process.35 Involvement of the entire community allows for a broader view of the problem, effective needs assessment, and a plan that fits within the paradigm of the community culture.24,28

Aftercare

Connectedness to one’s cultural group helps in health and recovery. Posttreatment success is highly dependent on the individual’s environment after addictions treatment.5,31 Many authors acknowledge the importance of continued support and aftercare, yet there is little written on the subject. Of the 3 articles we reviewed that focused on aftercare, only 1 was community-based, and all 3 had unreliable evaluation methods. The 1 study, which details a drug and alcohol addictions aftercare program for Natives in their community, looks at aftercare provided over the telephone to individuals (N = 30) who returned to the American reserve after treatment. After 6 months of regular aftercare through telephone contact, there was a reduction in drug- and alcohol-related symptoms.5

Successful aftercare in communities requires a long-term focus. In order to design a sustainable program, capacity building and community ownership are crucial. These are encouraged by implementing mechanisms for sustainable networks, resources, and support systems.6

Discussion

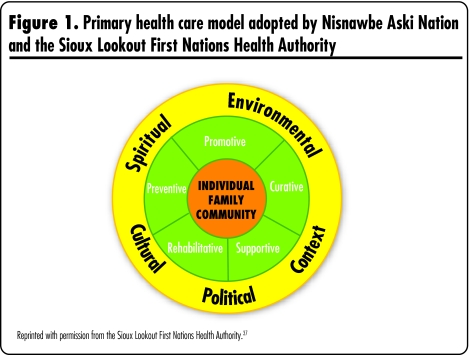

The concept of community healing is a developing area. Current western paradigms identifying determinants of health have much congruence with the holistic interactive components of the medicine wheel. While different communities have various versions of the model, the one used by the Sioux Lookout First Nations Health Authority (Figure 137) respects “traditional ways of knowing, being and healing in community,” which accept that “we must always view and address the ‘whole,’ the ‘spirit,’ to attain health.”37

Figure 1. Primary health care model adopted by Nisnawbe Aski Nation and the Sioux Lookout First Nations Health Authority.

Reprinted with permission from the Sioux Lookout First Nations Health Authority. 37

The relationship between community engagement and community health has developed out of theories such as social capital and cultural continuity.38,39 Another aboriginal organization, the Assembly of Manitoba Chiefs, chose the concept of social capital to identify and draw on the strengths of successful and healthy aboriginal communities.38 Similarly, the concept of cultural continuity was used to examine the inverse relationship between suicide rates and community efforts toward cultural preservation and community governance in British Columbia First Nations communities.39

The immediate benefit of community-based programs is that they might overcome many of the barriers to off-reserve residential programs. These barriers include fears of unknown larger centres and being away from work or family. Community-based programs allow individuals to be treated in familiar environments where they are surrounded by family and friends,6 thus promoting understanding of their illnesses within the communities they will rely on for posttreatment support.

Through political, economic, and administrative initiatives, community-based programs provide opportunities for capacity building and offer a viable alternative to costly residential programs, although sustainable funding is required for success. The long-term benefits of these programs are consistent with the holistic practices of aboriginal healing and community development, which allow for widespread community issues to be addressed at the root by the whole community. More than 1000 aboriginal healing programs have occurred in reserves and cities across Canada.40 Through these innovative and varied approaches, communities are addressing complex issues surrounding historical trauma, including addictions, sexual abuse, family violence, and suicide.

Limitations

The limitation of this literature is that community-based programs suffer from insufficient evaluation and outcome data. The paucity of evaluations can be attributed to the community-specific nature of the programs. Additionally, the objectives of community development, such as increased self-esteem, community spirit, and leadership, are inherently difficult to measure.19,40 Such changes in community culture can take many years, while evaluation needed for funding requires more immediate results.32 A creative mix of qualitative and quantitative baseline and postintervention longitudinal evaluation is required.29

Conclusion

Each aboriginal community is unique, and patterns and prevalence of drug and alcohol use differ widely. The complexity of the problem identified requires individual and flexible plans specific to the communities’ needs and objectives. While promoting community involvement and participatory processes in these programs, there is also a need for well-designed studies and increased research in the field, so that communities can draw on one another’s successes as they engage in community development and addictions treatment.

Community-based prevention and treatment modalities offer appropriate alternatives to traditional treatment approaches. The health and well-being of communities and their participation in such initiatives have positive effects on prevention, treatment, and aftercare. The key components of success appear to be strong leadership in this area, strong community-member engagement, paid positions for programming and organizing, and the ability to develop infrastructure for long-term program sustainability.

Levels of evidence

Level I: At least one properly conducted randomized controlled trial, systematic review, or meta-analysis

Level II: Other comparison trials, non-randomized, cohort, case-control, or epidemiologic studies, and preferably more than one study

Level III: Expert opinion or consensus statements

EDITOR’S KEY POINTS

In many remote aboriginal communities, treatment for alcohol or drug abuse involves referral to distant residential treatment programs. Those who complete these programs might return to the same situations and stressors with little or no aftercare. Relapse is common.

Community-based treatment programs incorporate preventive treatment and aftercare services within individuals’ home communities, and facilitate inclusion of cultural relevance.

The literature on aboriginal community-based treatment programs emphasizes the importance of viewing addiction through a sociocultural lens and enhancing community empowerment in the development of programs. However, there is a paucity of evaluation and outcome data for these programs.

POINTS DE REPÈRE DU RÉDACTEUR

Dans plusieurs collectivités autochtones éloignées, le traitement de l’alcoolisme et de la toxicomanie exige un séjour dans un établissement éloigné. À son retour, le patient risque de retrouver les mêmes situations et facteurs de stress, avec un suivi insuffisant ou absent. Les rechutes sont fréquentes.

Les programmes de traitement communautaires combinent des traitements préventifs et des services locaux de suivi adaptés à la culture.

La littérature sur les programmes communautaires de traitement en milieu autochtone insiste sur l’importance d’envisager la dépendance d’un point de vue socioculturel et d’amener la collectivité à élaborer elle-même les programmes. Il existe toutefois peu de données sur l’évaluation et les résultats de ces programmes.

Footnotes

*Full text is available in English at www.cfp.ca.

Cet article a fait l’objet d’une révision par des pairs.

Competing interests

None declared

Native is used throughout this article to refer to the indigenous and aboriginal inhabitants of North American and their descendants.

This article has been peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Indian and Northern Affairs Canada. Fall 2003 survey of First Nations people living on-reserve: integrated final report. Ottawa, ON: Ekos Research Associates Inc; 2004. [Accessed 2008 May 12]. Available from: www.ainc-inac.gc.ca/pr/pub/fns/2004/srv04_e.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Statistics Canada. Language, health and lifestyle issues: 1991 aboriginal peoples survey. Ottawa, ON: Statistics Canada; 1993. Catalogue no. 89-533. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Assembly of First Nations/First Nations Information Governance Committee. First Nations regional longitudinal health survey (RHS) 2002/03. Results for adults, youth and children in First Nations communities. 2. Ottawa, ON: Assembly of First Nations/First Nations Information Governance Committee; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Waldram JB, Herring DA, Young TK. Aboriginal health in Canada: historical, cultural, and epidemiological perspectives. 2. Toronto, ON: University of Toronto Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chong J, Herman-Stahl M. Substance abuse treatment outcomes among American Indians in the Telephone Aftercare Project. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2003;35(1):71–7. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2003.10399996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wiebe J, Huebert KM. Community mobile treatment. What it is and how it works. J Subst Abuse Treat. 1996;13(1):23–31. doi: 10.1016/0740-5472(95)02044-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Health Canada. Literature review. Evaluation strategies in aboriginal substance abuse programs: a discussion. Ottawa, ON: Health Canada; 1998. [Accessed 2008 May 12]. Available from: www.hc-sc.gc.ca/fnih-spni/pubs/ads/literary_examen_review/index_e.html. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chamberlin RB. A practical guide to implementing a mobile community treatment process for alcohol and drug abuse based on experiences in three small isolated non-treaty settlements. Arctic Med Res. 1991;(Suppl):271–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Robinson G, Warren H, Samu K, Wheeler A, Matangi-Karsten H, Agnew F. Pacific healthcare workers and their treatment interventions for Pacific clients with alcohol and drug issues in New Zealand. N Z Med J. 2006;119(1228):U1809. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Flores PJ. Alcoholism treatment and the relationship of Native American cultural values to recovery. Int J Addict. 1985;20(11-12):1707–26. doi: 10.3109/10826088509047258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beauvais F. An integrated model for prevention and treatment of drug abuse among American Indian youth. J Addict Dis. 1992;11(3):63–80. doi: 10.1300/J069v11n03_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mohatt GV, Hazel KL, Allen J, Stachelrodt M, Hensel C, Fath R. Unheard Alaska: culturally anchored participatory action research on sobriety with Alaska Natives. Am J Community Psychol. 2004;33(3-4):263–73. doi: 10.1023/b:ajcp.0000027011.12346.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fisher DG, Lankford BA, Galea RP. Therapeutic community retention among Alaska Natives. Akeela house. J Subst Abuse Treat. 1996;13(3):265–71. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(96)00060-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boyd-Ball AJ. A culturally responsive, family-enhanced intervention model. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2003;27(8):1356–60. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000080166.14054.7C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Scott KA, Myers AM. Impact of fitness training on native adolescents’ self-evaluations and substance use. Can J Public Health. 1988;79(6):424–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kahn MW, Fua C. Counselor training as a treatment for alcoholism: the helper therapy principle in action. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 1992;38(3):208–14. doi: 10.1177/002076409203800304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ellis BH., Jr Mobilizing communities to reduce substance abuse in Indian country. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2003;35(1):89–96. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2003.10399999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Franks C. Preventing petrol sniffing in aboriginal communities. Community Health Stud. 1989;13(1):14–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-6405.1989.tb00172.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Noe T, Fleming C, Manson S. Healthy nations: reducing substance abuse in American Indian and Alaska Native communities. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2003;35(1):15–25. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2003.10399989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Parker L, Jamous M, Marek R, Camacho C. Traditions andinnovations: a com -munity-basedapproach to substance abuse prevention. R I Med J. 1991;74(6):281–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smye V, Mussell B. Aboriginal mental health: what works best. A discussion paper. Vancouver, BC: Mheccu (Mental Health Evaluation and Community Consultation Unit), University of British Columbia; 2001. [Accessed 2008 May 12]. Available from: www.carmha.ca/publications/resources/pub_amhwwb/Aboriginal%20Mental%20Health%20-%20What%20Works%20Best%20[July%202001].pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mills PA. Incorporating Yup’ik and Cup’ik Eskimo traditions into behavioral health treatment. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2003;35(1):85–8. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2003.10399998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hitchen SR. Making connections that work: partnerships between vocational rehabilitation and chemical dependency treatment programs. Am Indian Alsk Native Ment Health Res. 2001;10(2):85–9. doi: 10.5820/aian.1002.2001.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Edwards RW, Jumper-Thurman P, Plested BA, Oetting ER, Swanson L Tri-Ethnic Center for Prevention Research, Colorado State University. Community readiness: research to practice. J Community Psychol. 2000;28(3):291–307. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Northern Alberta Field Services Division. Mobile treatment AADAC. Calgary, AB: Alberta Alcohol and Drug Abuse Commission; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Coates L. Saskatchewan: innovation produces alternatives to costly residential treatment [insert] Can Cent Subst Abuse Action News. 1991;2(6) [Google Scholar]

- 27.North Saskatchewan Alcohol and Drug Abuse Commission. Mobile community treatment program handbook. Regina, SK: Saskatchewan Health, North Saskatchewan Alcohol and Drug Abuse Commission; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Abbott PJ. Traditional and western healing practices for alcoholism in American Indians and Alaska Natives. Subst Use Misuse. 1998;3(13):2605–46. doi: 10.3109/10826089809059342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gray D, Saggers S, Drandich M, Wallam D, Plowright P. Evaluating government health and substance abuse programs for indigenous peoples: a comparative review. Aust J Public Health. 1995;19(6):567–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-6405.1995.tb00460.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.May PA. Alcohol and drug misuse prevention programs for American Indians: needs and opportunities. J Stud Alcohol. 1986;47(3):187–95. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1986.47.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gray D, Saggers S, Sputore B, Bourbon D. What works? A review of evaluated alcohol misuse interventions among aboriginal Australians. Addiction. 2000;95(1):11–22. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2000.951113.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Novins DK, Fleming CM, Beals J, Manson SM. Commentary: quality of alcohol, drug, and mental health services for American Indian children and adolescents. Am J Med Qual. 2000;15(4):148–56. doi: 10.1177/106286060001500405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.May PA. Alcohol policy considerations for Indian reservations and border-town communities. Am Indian Alsk Native Ment Health Res. 1992;4(3):5–59. doi: 10.5820/aian.0403.1990.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thurman PJ, Plested BA, Edwards RW, Foley R, Burnside M. Community readiness: the journey to community healing. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2003;35(1):27–31. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2003.10399990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mail PD. Do we care enough to attempt change in American Indian alcohol policy? Am Indian Alsk Native Ment Health Res. 1992;4(3):105–11. doi: 10.5820/aian.0403.1990.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.First Nations and Inuit Health. Treatment programs. Literature review. Evaluation strategies in aboriginal substance abuse programs: a discussion. Ottawa, ON: Health Canada; 1998. [Accessed 2008 Jun 2]. pp. 35–51. Available from: www.hc-sc.gc.ca/fnih-spni/pubs/ads/literary_examen_review/rev_rech_5_e.html. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sioux Lookout First Nations Health Authority. The Sioux Lookout Anishnabe District health plan: building a plan to improve our health. Sioux Lookout, ON: Sioux Lookout First Nations Health Authority; 2006. [Accessed 2008 Jan 19]. Available from: www.nodin.on.ca/dhp.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mignone J. Measuring social capital: a guide for First Nations communities. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Institute for Health Information; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chandler MJ, Lalonde C. Cultural continuity as a hedge against suicide in Canada’s First Nations. Transcult Psychiatry. 1998;35(2):191–219. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lane P, Bopp M, Bopp J, Norris J. Mapping the healing journey: the final report of a national research project on healing in Canadian aboriginal communities. Ottawa, ON: Solicitor General of Canada, The Aboriginal Healing Foundation; 2002. [Accessed 2008 May 12]. Available from: www.sgc.gc.ca. [Google Scholar]