Abstract

Background

Lack of updated and uniform medication lists poses a problem for the continuity in patient care. The aim of this study was to estimate whether hospitals succeed in making accurate medication lists congruent with patients' actual medication use. Subsequently, the authors evaluated where errors were introduced and the possible implications of incongruent medication lists.

Methods

Patients were visited within one week after discharge from surgical or medical department and interviewed about their use of prescription‐only medication (POM). Stored drugs were inspected. Medication lists in hospital files and discharge letters were compared with the list obtained during the interview. The frequency of incorrect medication use and the potential consequences were estimated.

Results

A total of 83 surgical and 117 medical patients were included (n = 200), 139 patients (70%) were women. Median age was 75 years. Six patients stored no POM, 194 patients stored 1189 POM. Among the 955 currently‐used POM, 749 POM (78%) were registered at some point during hospitalisation but only 444 (46%) were registered in discharge letters. 66 POM users had no medication list in their discharge letter. Local treatments (skin, eyes, airways) were registered less frequently than drugs administered orally. In total, 179 of the currently‐used POM (19%) were not mentioned anywhere in hospital files, probably because of insufficient medication lists made at admission, and the prescribed regimen was unclear. At least 63 POM (7% of currently‐used POM) were used in disagreement with the prescribed regimen.

Discussion

Approximately one fifth of used POM is unknown to the hospital and only half of used POM registered in discharge letters. Insufficient medication lists hamper clarifying whether or not patients use medication according to prescription. In order to prevent medication errors a systematic follow‐up after discharge focusing on making an updated medication list might be needed.

Polypharmacy is increasing.1 The request for individualised treatments of not only manifest diseases but also numerous risk factors is likely to further increase multidrug regimens.2 An important cause of medication‐prescribing errors leading to adverse drug events is polypharmacy combined with lack of knowledge of patients' medication use at time of prescribing.3,4,5

Upon hospitalisation the patient is often the primary source of information about a prescribed medication regimen. However, due to patients' recall bias supplementary information is often needed from district nurses, general practitioners or pharmacies.6,7 The lacking update of written registrations and the frequent involvement of several healthcare professionals hamper the overview of the currently‐prescribed drugs; medication lists may also be inconsistent.7,8,9,10,11 The frequent changes in prescribed medications during hospitalisations combined with erroneous discharge letters further add to the problem.12,13 This lack of updated and uniform medication lists poses a problem for the continuity in patient care with the risk of less effective treatment and adverse drug reactions.2

To evaluate clinical drug effects it is important to know the patient's current medication use.14,15 The patient does not always follow the prescribed regimen—either accidentally, due to misunderstandings, or deliberately.2,16 Medication reconciliation is a multistep process verifying variance between medical records and the patient's actual medication use followed by rectification of errors.17,18 Valid information about current medication use can best be collected when visiting patients in their own homes: the inspection of stored drugs combined with interviews about medication use reduces recall bias.19,20,21 However, this strategy has been used only to a limited degree as a method to verify the information on drug use available in hospital files related to hospitalisation.7

We wanted to investigate whether a hospital had succeeded in making medication lists congruent with patients' actual medication use. Previous studies have primarily focused on either the admission medication list22,23,24or the medication list in the discharge letter12,25 and we wished to do both, to differentiate where errors had been introduced. We collected information about patients' medication use after hospitalisation during home visits one week after the discharge. Patients' reported use was compared with the written registrations in (1) the discharge letter and (2) the full hospital file. Discrepancies were noted and the possible consequences evaluated. Incongruent lists might indicate a need for systematic medication reconciliation upon hospitalisation or a systematic follow‐up and evaluation of patients' medication use after discharge.

Material and methods

This cross‐sectional survey was conducted from November 2002 to March 2003 in a surgical and a medical department at a University hospital in Copenhagen, Denmark. The surgical department specialises in gastrointestinal diseases and the medical department in endocrine, gastrointestinal and pulmonary diseases. The Regional Ethics Committee and the Danish Registry Board approved the study. The drug company Pharmacia/Pfizer financially supported the study. However, the company was not involved in data collection, data analysis or manuscript preparation, and the authors had full ownership of the study data.

Patients scheduled for discharge were identified every weekday at 9 am and 12 noon. Patients were eligible for inclusion if they lived in their own home (sheltered housing included) and were able to speak Danish or English. After informed consent was obtained (written and verbal), patients were included consecutively until 200 home visits had been carried out.

The patients were interviewed in their home within the first week after discharge. The aim of the interview was to clarify the patient's medication use during the time period from hospital discharge until the home visit and to establish the duration of use of individual drugs. Some drugs used at discharge had been discontinued, new drugs were added, etc (fig 1). The interviewer asked the patients to present all their stored medications, and a structured drug interview lasting approximately one hour was performed. Packages and containers were inspected and the following information was recorded: drug name, prescription date, schedule and dosage. The patients were questioned about the prescriber of individual drugs and about the duration of drug use. Additionally, patients were asked to specify their current medication use and their medication use immediately following discharge. To make the patient as comfortable as possible, questions about drug use were asked in a non‐judgemental way. The interviewing physician had not been involved in patient care during the hospitalisation. If inconsistencies were noted in patient's drug regimen the patient was recommended to seek advice from treating physicians.

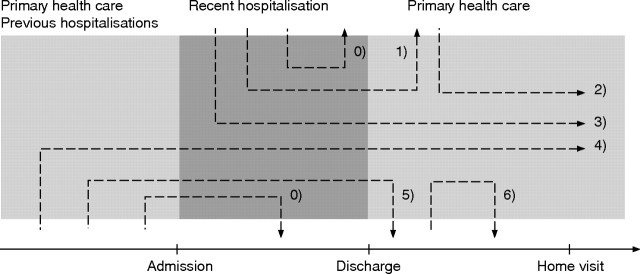

Figure 1 Schematic presentation of ordering and discontinuation of drugs in primary and secondary health care. The prescription‐only medication (POM) described in the present article were all used during the week following discharge. The duration of use might be subdivided into: 1. POM prescribed during hospitalisation and used at discharge but not used during home visit. 2. POM prescribed after discharge and used during home visit. 3. POM prescribed during hospitalisation and used during home visit. 4. POM prescribed before hospitalisation and used during home visit. 5. POM prescribed before hospitalisation and discontinued after discharge. 6. POM prescribed after discharge and discontinued before home visit. POM discontinued during hospitalisation (arrows 0) are not described.

Below only data regarding POM are presented, with POM defined as medications only available by prescription as apposed to over‐the‐counter products.

Current medication use was defined as the regimen the patient used at the time of the home visit. We used the following categories:

1. Used daily: POM used every day according to a regular schedule

2. Used on demand: POM used within the last month in response to specific symptoms

3. Not currently used: stored POM not used in the preceding month.

The drug regimen prescribed by the hospital was established from the medication lists in the discharge letter. Additional information on in‐hospital knowledge of drug use was established by scrutinising the drug lists registered upon admission and during hospitalisation. These overall registrations on prescribed drug regimen (arrows 1, 3, 4, 5 in fig 1) were compared to patients' reported POM use immediately after discharge and discrepancies noted.

Statistics

The use of medications was reported using descriptive statistics. We used χ2 tests (for categorical data) and two‐sample t tests (for continuous data) for comparison of independent groups of data. Cut‐off level for statistical significance was 0.05. The statistics were calculated with SAS 9.1.

Results

Overall, 256 patients were screened for inclusion. Of these, 56 patients were excluded due to readmission (n = 7), withdrawn consent (n = 47) or death within one week after discharge (n = 2). The included and excluded patients were similar regarding age (mean 72 v 70 years, p = 0.36) and sex (women/men 139/61 v 41/15, p = 0.59).

A total of 200 home visits were conducted. Eighty three patients (42%) had been discharged from the surgical department and 139 (70%) were women. The median age was 75 years (range 24–100 years). Overall, 171 patients (86%) were retired or receiving social security. One hundred and twenty eight patients (64%) personally dispensed all drugs. District nurses assisted in 51 cases (26%) and relatives assisted in 21 cases (11%). The median length of hospital stay was 7 days (range 1–155 days) for surgical and 7 days (range 2–38 days) for medical patients. The primary diagnoses as recorded in the discharge letters were pulmonary diseases (n = 65, 33%), gastrointestinal diseases (n = 62, 31%), malignant diseases (n = 21, 11%), diseases of the liver, pancreas or bile ducts (n = 18, 9%) or other diseases (n = 34, 17%). One hundred and fifty eight patients (79%) had been admitted to hospital due to acute illnesses.

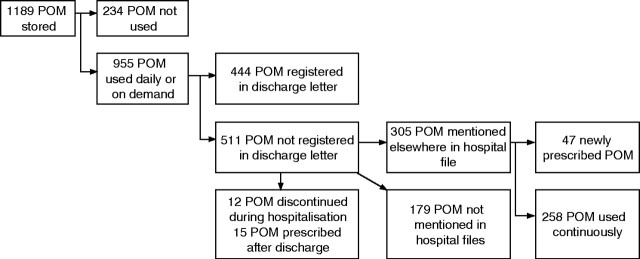

A total of six patients stored no POM and the remaining 194 patients (97%) stored 1189 POM in their homes (median 5 POM per patient, range 0–19) of which 955 POM were currently used daily or on demand (median 4 POM per patient, range 0–19) (arrows 2, 3 and 4, fig 1) (fig 2). The 955 POM included 15 POM prescribed after discharge (arrow 2, fig 1); 14 POM had been used at discharge but were discontinued at the home visit (arrows 1 and 5, fig 1). All patients had a discharge letter from recent hospitalisation. A systematic examination of all registrations in hospital files, discharge letters, etc showed that 444 of the used POM (46%) were registered in discharge letters and another 305 POM (31%) were registered elsewhere in hospital files giving an overall registration of 78%. The overall registration (discharge letter or hospital file) and the registration in the discharge letter was significantly higher among medical compared with surgical patients (p<0.001). A total of 80 patients had no medication list in the discharge letter at all, including 14 patients reporting no POM use at discharge and 66 patients (55 surgical and 11 medical patients) reporting use of one or more POM at discharge.

Figure 2 Prescription‐only medication (POM) storage and use at home visit. Registration of used drugs in hospital files and discharge letters.

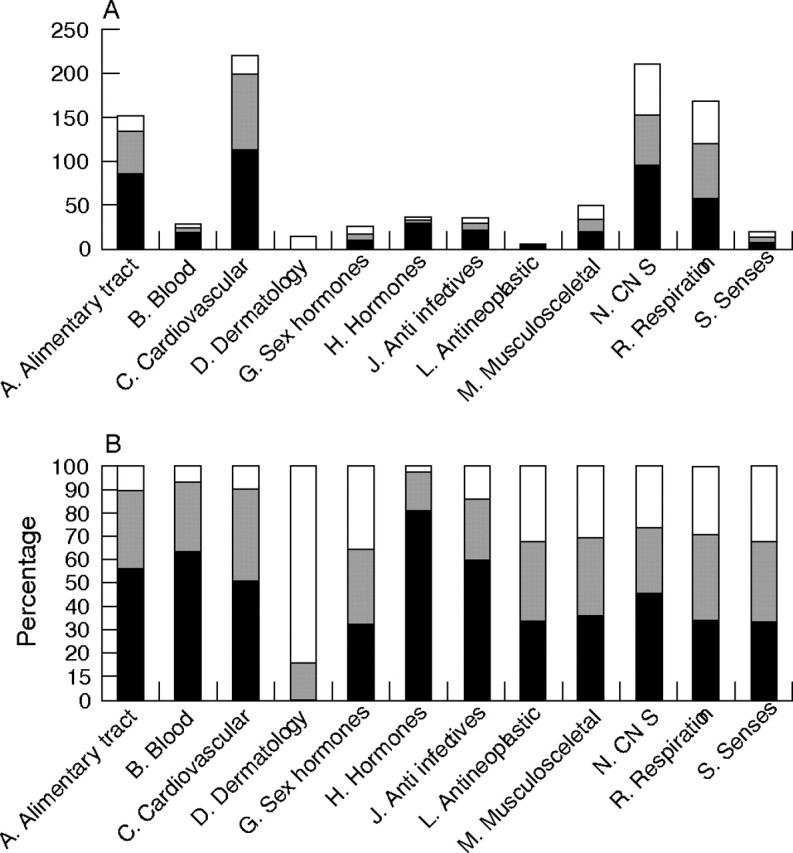

Figure 3A shows used POM subdivided by Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical Classification System, ATC‐code.26 Proton pump inhibitors (A02), diuretics (C03), strong analgesics (N02), anxiolytics (N05) and inhalation therapies in obstructive airway disease (R03) were the drugs used most frequently. As shown in figure 3A and B incongruent registrations were present in all ATC groups. Oral blood glucose lowering drugs (A10), antithrombotic drugs (B01), cardiovascular drugs (C), hormones (H02 corticosteroids, H03 thyroid therapy) and antibiotics (J) were the categories most frequently having congruent registrations estimated as per cent of total. Strong analgesics (N02), anxiolytics (N05) and sex hormones (G03) had congruence rates below 50% in the overall registrations (specific data not shown). Among medical patients the congruence was lower for local treatments (eye drops, inhalation therapy and dermatological treatments) compared to systemic treatments (for example, tablets, suppositories) (p<0.001). The surgical patients had low congruence irrespective of the administration route (p = 0.07). When comparing the drug regimen prescribed in the hospital files/discharge letters to the regimen followed by patients obvious discrepancies were noted in 63 POM (34 patients): 11 prescribed drugs were not used at all (table 1), 12 drugs discontinued during recent hospitalisation were still used (table 2), and 40 POM were used in other doses or regimens than prescribed (table 3). The POM not used by patients consisted of inhalation therapy in obstructive airway disease, analgesics and sedatives. These POM are mainly used as symptom‐limiting therapy and the clinical implications of incongruent use are likely to be minor. One patient did not use prescribed esomeprasol in ulcer disease and one patient had discontinued prescribed dipyridamole—both causing lack of preventive effect. Among the 12 POM discontinued during hospitalisation but still used by patients were nine POM administered as tablets with potentially harmful effects due to use of an unnecessary and unmonitored treatment.

Figure 3 (A) Total number of prescription‐only medication (POM) used at time of home visit (n = 955) subdivided by ATC code. Black bar: POM registered in discharge letter. Striped bar: POM registered elsewhere in hospital files. White bar: POM not registered in hospital files. (B) Percentage of POM in each ATC group registered in discharge letter or elsewhere in hospital file subdivided by ATC code. Black bar: Percentage of POM registered in discharge letter. Striped bar: Percentage of POM registered elsewhere in hospital files. White bar: Percentage of POM not registered in hospital files.

Table 1 Eleven prescription‐only medications prescribed in discharge letter but not used during home visit: potential implications.

| Sex | Age (years) | Drug | Indication | Implication of non‐use |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 92 | Zopiclone | Insomnia | Limited |

| Budesonide inhalation | COPD | Limited | ||

| Female | 88 | Codeine | Analgesic | Limited |

| Female | 54 | Esomeprazole | Gastric ulcer | Lacking prophylaxis |

| Female | 83 | Tiotropium inhalation | COPD | Limited |

| Female | 64 | Clonazepam | Anxiety | Limited |

| Female | 62 | Budesonide inhalation | COPD | Limited |

| Male | 78 | Formoterol inhalation | COPD | Limited |

| Female | 85 | Dipyridamole | Apoplexia cerebri | Lacking prophylaxis |

| Female | 63 | Budesonide inhalation | COPD | Limited |

| Female | 66 | Salmeterol inhalation | COPD | Limited |

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Table 2 Twelve prescription‐only medications discontinued during hospitalisation but still used by patient: potential implications.

| Sex | Age, years | Drug | Indication | Reason for discontinuation | Implication of use |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 62 | Codeine | Analgesic | Acetaminophen prescribed instead | Risk of constipation. Patient with resected colon |

| Female | 91 | Trandolapril | Not stated | No reason stated | Risk of harmful effects of an unnecessary treatment |

| Bendroflumethiazide | Not stated | No reason stated | Risk of harmful effects of an unnecessary treatment | ||

| Tramadol | Analgesic | No reason stated | Risk of harmful effects of an unnecessary treatment | ||

| Female | 61 | Diazepam | Muscular relaxant, analgesic | No reason stated | Risk of misuse |

| Ibuprofen | Analgesic | No reason stated | Risk of harmful effects of an unnecessary treatment | ||

| Female | 77 | Terbutaline | COPD | Ipratropium/feneterol combination treatment prescribed instead | Limited |

| Salbutamol | COPD | Unnecessary double treatment | |||

| Female | 66 | Salmeterol | COPD | Salmeterol/fluticason combination inhalation prescribed instead | Limited |

| Female | 75 | Digoxin | Atrial fibrillation | Sinusrhytm | Risk of harmful effects of an unnecessary treatment |

| Female | 88 | Metformin | Diabetes | Stable blood sugars | Risk of hypoglycaemia |

| Spironolactone | Diuretic | Renal insufficiency | Risk of hyperkalaemia |

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Table 3 Forty prescription‐only medications used in different doses or regimens than prescribed in discharge letter.

| Sex | Age (years) | Drug | Prescribed use | Actual use | Indication for use | Implication of incongruent use |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | 85 | Nifedipine | 60 mg ×1 | 60 mg ×2 | Hypertension | Risk of hypotension |

| Female | 76 | Glimepiride | 3 mg ×1 | 6 mg ×1 | Diabetes | Risk of hypoglycaemia |

| Male | 62 | Terbutaline | 7.5 mg ×1 | 7.5 mg ×2 | COPD | Risk of side effects |

| Female | 82 | Isosorbide dinitrate | 80 mg ×1 | 80 mg ×2 | Angina pectoris | Risk of hypotension |

| Female | 64 | Citalopram | 20 mg ×1 | 10 mg ×1 | Depression | Risk of insufficient treatment |

| Female | 58 | Citalopram | 90 mg ×1 | 60 mg ×1 | Depression | Unprescribed but probably relevant dose reduction |

| Female | 79 | Levothyroxine | 0.1 mg ×1 and 0.15 ×1 on alternate days | 0.1 mg ×1 and 0.2 ×1 on alternate days | Hypo‐thyreoidism | Dose reduced during hospitalisation. Poorer regulation of myxoedema |

| Male | 57 | Phenobarbital | 100 mg ×1 | 100 mg ×2 | Epilepsy | Risk of side effects |

| Female | 88 | Allopurinol | 100 mg ×2 | 100 mg ×1 | Gout | Risk of insufficient treatment |

| Male | 79 | Verapamil | 240 mg ×1 | 240 mg ×2 | Heart arrhythmia | Risk of hypotension |

| Female | 91 | Nitrofurantoin | 50 mg ×1 | 25 mg ×1 | Chronic cystitis | Risk of insufficient treatment |

| Female | 52 | Omeprazole | 20 mg ×2 | 20 mg ×3 | Ulcer | Risk of side effects |

| Female | 79 | Esomeprazole | 40 mg ×1 | 20 mg ×1 | Ulcer | Risk of insufficient treatment |

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Other prescription‐only medication used in different doses and/or regimens than prescribed: inhalation therapy in obstructive pulmonary disease (11 patients), analgesics (6 patients), diuretics (2 patients), sedatives (6 patients), others (2 patients).

For example, the 91‐year‐old female still using trandolapril, bendroflumethiazide and tramadol explained dissatisfaction with the medication list provided from the hospital after discharge as several of the regularly‐used drugs were omitted. She considered this as a mistake and resumed the treatment. She lived with her husband and did not wish to receive help with medication dispensing from a district nurse. However, according to the hospital file the drugs were discontinued during hospitalisation due to confusion, dehydration and low sodium level. As shown in table 3 the incongruent use of, for example, cardiovascular and psycotrophic drugs implied the risk of either under‐ or overtreatment. A 76‐year‐old woman using glimepiride 6 mg daily and hospitalised as a result of coma caused by hypoglycaemia exemplifies this. The treatment with glimepiride was reduced to 3 mg daily during hospitalisation to be continued after discharge, but the patient resumed her customary dosing of 6 mg. However, none of the patients reported daily‐used doses higher than recommended by the Danish Medicines Agency.27 The patients reported continuous use of 179 POM before and after hospitalisation which was not registered anywhere in the hospital files. As this lack of registration rendered it difficult to establish whether the patients used the drugs according to prescription, these drugs were not included in the above evaluation of congruence.

Regarding the 955 POM patients used at the time of the home visit, the patients reported that 691 POM had been prescribed before recent hospitalisation (269 (28%) by a hospital physician, 355 POM (37%) by general practitioners, 67 drugs (7%) by other physicians), 143 (15%) had been prescribed during recent hospitalisation and 15 drugs (2%) had been prescribed after discharge. The patients could not recall the prescribers of 106 POM (11%). Among the 143 POM prescribed during recent hospitalisation (79 patients, median 0 POM per patient, range 0–5), 47 POM covering various drug categories (for example, 10 antibiotics, 6 sedatives, 7 analgesics, 7 POM to treat gastric ulcer) were not mentioned in the discharge letter (34 patients). Drugs prescribed by general practitioners were registered less frequently in hospital files/discharge letters than drugs prescribed by hospital physicians (69% v 89%, p<0.001).

Discussion

In this study, performed among surgical or medical patients recently discharged from hospital, one out of five drugs used by patients after hospitalisation were unknown to the hospital. In particular, drugs prescribed by general practitioners were not registered in hospital files. Frequently, information was lost at time of discharge and only half of used POM were mentioned in the discharge letters. The missing registrations made it very difficult to conclude whether patients used POM as prescribed, but a number of obvious inconsistencies with potential harmful effects were noted.

Knowledge of any drugs the patient is using is a prerequisite of the proper evaluation of patients, irrespective of the setting in either hospitals or primary health care.4,5 Drug interactions, adverse drug effects or drug interference with the underlying disease can be the consequences of errors in medication histories28 and errors of omission may lead to overprescribing.23,29

Patients recently discharged from hospital must be expected to have updated medication histories. During hospitalisations a natural part of patient treatment is the evaluation of former drug treatment and further indication, and the prescription of new drugs. However, as illustrated in figure 1, this process is quite complicated with multiple prescribers being involved at different time‐points. Therefore, in the present study we wished to estimate whether the hospital had succeeded in making an updated medication list—and whether this list was successfully communicated to general practitioners in the discharge letter. We also wanted to detect if missing registrations in the discharge letter was the results of either the drug being completely unknown to the hospital or to insufficient registrations of known drugs at the discharge stage.

In Denmark the only written communication between hospital and primary health care at discharge is the discharge letter. Hence this communication is essential to ensure continuity in care.25,30,31,32 Local or hospital pharmacies are not involved in discharge planning. All discharge letters should describe current medication use and reasons for major changes in previously‐used medications (Copenhagen Hospital Corp. Discharge Summary—Policy, 2003). It is estimated that 20% of discharges lead to readmissions, partly because of lack of communication between hospitals and primary care.25 Our finding that half of used drugs are not registered in discharge letters is not surprising and in congruence with previous studies.6,24,28 The discharge letters were inadequate especially among surgical patients and 55 of 83 surgical patients (66%) had no medication list in the discharge letter. Serious errors of omission were medications prescribed during hospitalisation not registered in the discharge letter. It is however surprising that the overall registrations in hospital files included nearly 80% of used drugs. Thus, much information was lost at time of discharge.

The 19% of POM not known to hospitals were more frequently prescribed by general practitioners. This illustrates a lack of communication between healthcare sectors. Such omission errors are most likely introduced on admission due to patient recall bias and perhaps insufficient effort to collect information from general practitioners and other treating physicians. Patients' resumption of use after discharge may lead to overprescribing or adverse effects.31

At least 5% of POM were used differently than prescribed. Discontinued drugs still used by patients were a particular matter of concern due to potential lack of monitoring. The incongruence found in psychotropic medications and analgesics may be perceived as intelligent non‐adherence: the patient discontinues medication when a condition improves.2,33,34 However, such practise may be problematic as patients unintentionally under‐ or overdose if they autonomously alter doses and regimens.35,36

This study has some limitations. Errors of commission (that is, drugs recorded by physician but not used by patient)28 were not included in the evaluation of medication lists in hospital files and discharge letter. Patients were interviewed about their general medication use; day‐to‐day variations and adherence rates were not recorded. Data regarding drug use depend on patients' verbal information and it is possible that disagreements between the prescribed and used POM regimen was underestimated due to underreporting. Furthermore, we did not distinguish between incongruent use due to misunderstanding and miscommunication versus patients deliberately not following prescriptions. We defined incongruence as any inconsistency between the actual uses of drugs in contrast to the regimen prescribed according to the hospital files. This reflected our viewpoint that medication lists should reflect patients' actual actions. If patients are non‐adherent to drugs, for example because they do not find the drugs effective or the drugs have side effects, drug lists should be corrected correspondingly. However, some authors find it more relevant to compare patients' understanding of the prescribed drug regimen to medication lists in order to separate non‐adherence from the perceived regimen.2

Wide improvements must be made in this area—sufficient drug lists upon admission to hospital, during hospital stay and lastly in the discharge letter are essential to ensure an updated and correct medication list. On admission secondary interviews, collection of information from general practitioners and pharmacies has proven effective in complementing drug lists.23,24 Systematic medication reconciliation applied at hospital admission or discharge may prevent medication errors and adverse events.37,38 The process of reconciliation includes comparison of available medication lists (for example, from general practitioners, district nurses, pharmacy records) to patient's current medication use. This is followed by a clinical decision and communication of a new, common list to the patient and caregivers. In Denmark, pharmacy records on POMs handed out from a Danish pharmacy in the preceding two years are now available directly online by use of a digital signature.39 Such data may reduce recall bias and thus improve information on used medications, and the direct access to the records makes them also useful outside of a research setting.40

In the current study, much information otherwise available in the hospital files was lost at discharge. Electronic medication lists are now available in some Danish hospitals; these lists implemented at discharge could be beneficial. Medication reviews and systematic counselling by nurses or pharmacists are other ways to improve the lists.38,41,42 Joint formularies and standard lists used between healthcare sectors, perhaps in an electronic form linking to pharmacy records, are other ways to improve continuity in care. However, less is known about the cost effectiveness of these interventions to reduce medication errors.42

Follow‐up after discharge may be needed especially if patients are not well informed about medication changes. The setting could be in the patient's own homes, the general practitioner's office or in a hospital ambulatory setting.20,21 Interview accompanied by the inspection of medication containers facilitates a medication list congruent with patient's actual medication use and possible misunderstandings may be rectified. This would improve the information on not only used POM but also over‐the‐counter products.44,45

In summary, our data show that the hospital has no knowledge of one fifth of used POM and reports only half of used drugs in the discharge letter. Erroneous medication lists are most likely introduced because of insufficient registrations at admission and omissions at discharge. It is important to address these issues further and to improve the communication between primary and secondary care in order to prevent inappropriate medication use and adverse drug effects. Systematic follow‐up after discharge focusing on an updated medication list might be effective in reducing medication errors.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Pharmacia/Pfizer for financial support and the nurses and secretaries at H:S Bispebjerg Hospital for their assistance. We thank E Spang‐Hanssen, MD, for assistance with data collection.

Abbreviations

ATC - Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical Classification System, ATC

POM - prescription‐only medication

References

- 1.Avorn J. Polypharmacy. A new paradigm for quality drug therapy in the elderly? Arch Intern Med 20041641957–1959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bikowski R M, Ripsin C M, Lorraine V L. Physician‐patient congruence regarding medication regimens. J Am Geriatr Soc 2001491353–1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burda S A, Hobson D, Pronovost P J. What is the patient really taking? Discrepancies between surgery and anesthesiology preoperative medication histories. Qual Saf Health Care 200514414–416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leape L L, Bates D W, Cullen D J.et al Systems analysis of adverse drug events. ADE Prevention Study Group. JAMA 199527435–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lesar T S, Briceland L, Stein D S. Factors related to errors in medication prescribing. JAMA 1997277312–317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cochrane R A, Mandal A R, Ledger‐Scott M.et al Changes in drug treatment after discharge from hospital in geriatric patients. BMJ 1992305694–696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Foss S, Schmidt J R, Andersen T.et al Congruence on medication between patients and physicians involved in patient course. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 200459841–847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rabol R, Arroe G R, Folke F.et al [Disagreement between physicians' medication records and information given by patients]. Ugeskr Laeger 20061681307–1310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barat I, Andreasen F, Damsgaard E M. Drug therapy in the elderly: what doctors believe and patients actually do. Br J Clin Pharmacol 200151615–622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van der Kam W J, Meyboom d J, Tromp T F.et al Effects of electronic communication between the GP and the pharmacist. The quality of medication data on admission and after discharge. Fam Pract 200118605–609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Neily J, Ogrinc G, Weeks W B. Reducing medication confusion in homebound patients: when the data do not conform to the initial hypothesis. Jt Comm J Qual Saf. 2003;29: 199–200, 157, [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Wilson S, Ruscoe W, Chapman M.et al General practitioner‐hospital communications: a review of discharge summaries. J Qual Clin Pract 200121104–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lisby M, Nielsen L P, Mainz J. Errors in the medication process: frequency, type, and potential clinical consequences. Int J Qual Health Care 20051715–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haynes R B, McKibbon K A, Kanani R. Systematic review of randomised trials of interventions to assist patients to follow prescriptions for medications. Lancet 1996348383–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cramer J A, Mattson R H, Prevey M L.et al How often is medication taken as prescribed? A novel assessment technique. JAMA 19892613273–3277. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barat I, Andreasen F, Damsgaard E M. Drug therapy in the elderly: what doctors believe and patients actually do. Br J Clin Pharmacol 200151615–622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations Available at http://www.jointcommission.org (accessed December 2006)

- 18.Aspden P, Wolcott J, Bootman J L.et al Preventing medication errors: Quality Chasm series. National Academy of Sciences. Available at http://www.nas.edu (accessed December 2006)

- 19.Barat I, Andreasen F, Damsgaard E M. The consumption of drugs by 75‐year‐old individuals living in their own homes. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 200056501–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yang J C, Tomlinson G, Naglie G. Medication lists for elderly patients: clinic‐derived versus in‐home inspection and interview. J Gen Intern Med 200116112–115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Atkin P A, Stringer R S, Duffy J B.et al The influence of information provided by patients on the accuracy of medication records. Med J Aust 199816985–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cornish P L, Knowles S R, Marchesano R.et al Unintended medication discrepancies at the time of hospital admission. Arch Intern Med 2005165424–429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lau H S, Florax C, Porsius A J.et al The completeness of medication histories in hospital medical records of patients admitted to general internal medicine wards. Br J Clin Pharmacol 200049597–603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Andersen S E, Pedersen A B, Bach K F. Medication history on internal medicine wards: assessment of extra information collected from second drug interviews and GP lists. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 200312491–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rubak S L, Mainz J. [Communication between general practitioners and hospitals]. Ugeskr Laeger 2000162648–653. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.WHO Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methology Guidelines for ATC‐classification and DDD assignment (2nd edition) p. 1998.

- 27.Dansk Lægemiddelinformation A/S Lægemiddelindustriforeningen p. 2005.

- 28.Beers M H, Munekata M, Storrie M. The accuracy of medication histories in the hospital medical records of elderly persons. J Am Geriatr Soc 1990381183–1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Price D, Cooke J, Singleton S.et al Doctors' unawareness of the drugs their patients are taking: a major cause of overprescribing? BMJ (Clin Res Ed) 198629299–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Solomon J K, Maxwell R B, Hopkins A P. Content of a discharge summary from a medical ward: views of general practitioners and hospital doctors. J R Coll Physicians Lond 199529307–310. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Himmel W, Kochen M M, Sorns U.et al Drug changes at the interface between primary and secondary care. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther 200442103–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Himmel W, Tabache M, Kochen M M. What happens to long‐term medication when general practice patients are referred to hospital? Eur J Clin Pharmacol 199650253–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Spagnoli A, Ostino G, Borga A D.et al Drug compliance and unreported drugs in the elderly. J Am Geriatr Soc 198937619–624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cooper J K, Love D W, Raffoul P R. Intentional prescription nonadherence (noncompliance) by the elderly. J Am Geriatr Soc 198230329–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kinsman R A, Dirks J F, Dahlem N W. Noncompliance to prescribed‐as‐needed (PRN) medication use in asthma: usage patterns and patient characteristics. J Psychosom Res 19802497–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kelloway J S, Wyatt R A, Adlis S A. Comparison of patients' compliance with prescribed oral and inhaled asthma medications. Arch Intern Med 19941541349–1352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bourke J L, Bjeldbak‐Olesen I, Nielsen P M.et al [Joint charts in drug handling. Toward increased drug safety]. Ugeskr Laeger 20011635356–5360. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pronovost P, Weast B, Schwarz M.et al Medication reconciliation: a practical tool to reduce the risk of medication errors. J Crit Care 200318201–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Danish Medicines Agency Available at http://www.laegemiddelstyrelsen.dk (accessed December 2006)

- 40.Larsen M D, Nielsen L P, Jeffery L.et al [Medication errors on hospital admission]. Ugeskr Laeger 20061682887–2890. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schnipper J L, Kirwin J L, Cotugno M C.et al Role of pharmacist counseling in preventing adverse drug events after hospitalization. Arch Intern Med 2006166565–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vira T, Colquhoun M, Etchells E. Reconcilable differences: correcting medication errors at hospital admission and discharge. Qual Saf Health Care 200615122–126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Duerden M, Walley T. Prescribing at the interface between primary and secondary care in the UK. Towards joint formularies? Pharmacoeconomics 199915435–443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Glintborg B, Andersen S E, Spang‐Hanssen E.et al The use of over‐the‐counter drugs among surgical and medical patients. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 200460431–437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Glintborg B, Andersen S E, Spang‐Hanssen E.et al Disregarded use of herbal medical products and dietary supplements among surgical and medical patients as estimated by home inspection and interview. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 200514639–645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]