Abstract

Objective

To describe the implementation and evaluation of a web‐based medication error reporting system.

Design

Evaluation study.

Setting

Long‐term care.

Participants

25 nursing homes in the US state of North Carolina.

Intervention

Detailed information about all medication errors occurring in a facility during a 1 year period was entered into a web‐based reporting system. An evaluation survey was conducted to assess usability and the potential for the system to prevent errors.

Main outcome measures

Number and specific characteristics of medication errors reported. A survey evaluating ease of use of the system and whether the participants thought it would help improve medication safety.

Results

23 (92%) sites entered 631 error reports for 2731 discrete error instances when weighted by the number of times the errors were repeated. 51 (8%) errors were classified as having a serious patient impact requiring monitoring/intervention or worse. The most common errors were dose omission (203, 32%), overdose (91, 14%), underdose (43, 7%), wrong patient (38, 6%), wrong product (38, 6%), and wrong strength (38, 6%). Errors most commonly occurred during medication administration (296, 47%) and were attributed to basic human error (402, 48%). Seven drugs were implicated in a third (175, 28%) of all errors: lorazepam, oxycodone, warfarin, furosemide, hydrocodone, insulin and fentanyl. 20 sites (86% of respondents) completed the evaluation survey and participants found the system easy to use and thought it would increase accuracy of reporting and improve patient safety.

Conclusions

The web‐based medication error reporting system was easy to use, with strong indications that it would be a valuable tool for preventing future errors.

In recent years, much attention has been focused within the acute care hospital setting on preventing the most common type of medical error—that is, medication errors. Much less effort, however, has been focused on preventing medication errors in the long‐term care setting, even though in the US alone an estimated 800 000 preventable medication‐related injuries occur every year in long‐term care facilities,1,2,3 and long‐term care patients are probably subject to more medication errors on average than patients in acute care hospitals.3 In many of the world's developed countries the number of disabled elderly people requiring support in a long‐term care setting is growing, and these countries are facing increased pressure to provide the highest quality and safest care possible. A survey of 10 developed countries found projected increases in the percentage of the elderly population from 35% to 99% by 2025, with between 2% and 14.5% of elderly people residing in some form of long‐term care setting.4

Many reasons exist for the disparity between the efforts made by acute care and long‐term care settings to prevent error, including the use of health information technologies with built‐in medication error detection and prevention features by hospitals,5,6 such as electronic health records, computerised physician order entry systems, computerised decision support systems, electronic prescribing and barcode unit dosing. The long‐term care sector lags far behind in the use of these technologies.7 But given the high risk of medication error in long‐term care, there is a crucial need to understand and prevent these errors. One potentially feasible method of addressing errors in long‐term care that does not require a high‐tech investment is adverse event or error reporting, a process that has been used successfully in hospitals and in high‐risk industries such as aviation.8 Adverse event reporting systems do not capture all errors since they rely on spontaneous reporting,9,10,11 but they help identify the root causes and patterns of errors and near misses, and provide valuable information for quality improvement efforts.8,9,12,13,14

Web‐based or electronic error reporting systems are particularly effective in increasing the quantity and quality of reporting and yielding the type of information needed for improving care.15,16,17,18,19 A recent review of the literature20 found information on 21 web‐based medical error/adverse event reporting systems; however, only one of these systems was used in a long‐term care setting. The institutions reporting on these systems stated that they had a positive impact on the process of medical error reporting at their facility. Clearly, a need exists to investigate the use of web‐based medication error reporting in long‐term care.

We report on an evaluation study of the initial implementation of a large scale web‐based medication error reporting system, a part of a quality initiative on medication error in long‐term care in the US state of North Carolina. In 2003, the state passed legislation requiring its approximately 400 nursing homes to report all medication errors on an annual basis. Besides actual errors, a medication error is defined to include potential errors and near misses. All error reports are confidential, and nursing homes are also required to establish internal medication management advisory committees to review error incidents and recommend changes to improve the safety of medication care.

During the first 2 years of the programme, nursing homes simply submitted an annual summary report of their medication errors to the state.21,22 But this method had many drawbacks, including a lack of detail about the errors and no useful feedback to reporting facilities. A decision was made in the third year of the programme to take the next step and develop and test a web‐based individual incident medication error reporting system. This new system allows nursing homes to enter online information about each individual error as it occurs. The system collects detailed information, covering all aspects of each error incident, including identification of specific medications involved in errors by using an innovative comprehensive online drug database. And finally, the system provides nursing homes with on‐demand summary and analysis reports of their errors for use in quality improvement efforts.

The aims of this implementation study were to assess the feasibility of nursing homes using a web‐based error reporting system, given the constraints facing these types of facility, such as lack of time, frequent staff turnover, suboptimal computer infrastructures and staff members who may not be sophisticated users of web technology and to find out how nursing homes perceived the new system. To determine their attitudes we asked them to evaluate the system in terms of ease of use, and whether they thought the system would help improve the accuracy and completeness of error reporting, and whether the summary reports produced by the system would be useful in guiding changes to improve medication safety at their facility. We also aimed to evaluate the new system in terms of numbers of errors, error types, patient outcomes and medical effects, error causes, medications and staffing categories involved, and how these new data compared with the previous years' summary data reporting.

Methods

Development of the reporting system

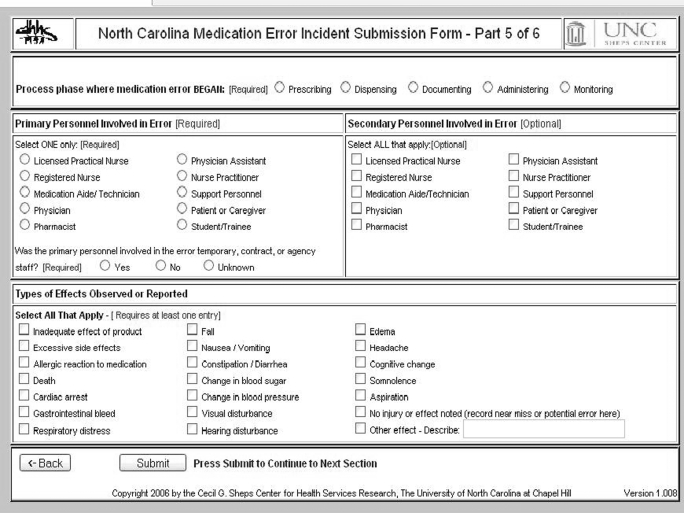

We developed the system in the spring of 2006. The error reporting form contains nine sections covering all aspects of the medication error:

Patient impact or level of harm to patient—nine categories ranging from a near miss that did not reach the patient to an error that caused or contributed to a patient death.

Patient information—age, gender, cognitive ability, whether the patient was moving into the facility, number of medications the patient was taking.

Incident information—date of incident, shift, number of times error was repeated.

Primary type of medication error—17 categories including overdose, underdose, wrong medication, wrong patient.

Phase of medication care process where error first occurred—prescribing, dispensing, documenting, administering and monitoring.

Primary and secondary personnel involved in error—10 categories including doctor, pharmacist, registered nurse, licensed practical nurse.

Medical effects of the error on patient—20 categories covering specific medical effects, such as respiratory distress, headache, excessive side effects, change in blood sugar, cardiac arrest, gastrointestinal bleed, death of patient.

Causes or reasons for error—22 categories including medication name confusion, illegible handwriting, poor communication, basic human error.

Specific medication(s) involved in the error—selected by user from a database of over 6000 prescription drugs, over‐the‐counter drugs, vitamins, herbal medicines and nutritional supplements.

When developing the system it was considered essential that the user interface should be easy and take minimal time to use, since it has been shown that one of the main barriers to medical error reporting is the perceived time and extra work required in reporting the error.23 Also, because of the high turnover among the nursing home staff, a system that required formal training sessions before a user was deemed competent to use the system was considered infeasible. The system was designed so that almost any user can log in and is guided step by step to enter the correct information needed to complete a report, tailored for the specific type of error (fig 1). For example, if the error type is overdose, then the system prompts for both intended dose and actual dose administered; if the error type is wrong medication, then the system prompts for both the intended and actual medications given.

Figure 1 Sample screen from reporting system.

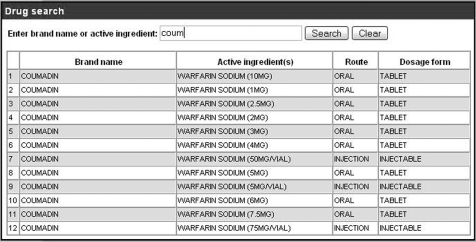

One of the most innovative aspects of the system is the drug identification tool that allows users to quickly search a comprehensive drug database and select the exact medication involved in the error, including the drug strength, route and dosage form (fig 2). The system allows the user to search by typing part of the drug name (brand or generic) and returns more focused matches the more letters that are typed. As our core database we used the downloadable US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) database, later creating and adding auxiliary databases of vitamins, over‐the‐counter drugs and herbal medicines. These databases can be easily updated as new drugs come to market. As spelling mistakes can be common with medication reporting, the search has a built‐in feature that provides alternative spellings based on a phonetic algorithm.

Figure 2 Sample medication search.

And lastly, since one of the crucial elements of an effective error reporting system is feedback to reporters, on‐demand summary reports have been incorporated into the system. At any time a user can create and print a summary of all errors entered to date, categorised by time period, patient impact, type of error and other relevant variables.

Study design and participant recruitment

What is already known on this subject

Several studies have shown that the rate of medication error in long‐term care is substantial and probably exceeds that of acute care hospitals.

Hospitals are beginning to use various health information technologies to detect and reduce medication errors, but long‐term care facilities generally do not have access to such technology.

Until now no system for improving medication safety and reducing errors has been implemented and evaluated in a long‐term care setting.

A total of 25 nursing homes tested the new system over a 4‐month period, entering all errors occurring at their facility during that time, as well as their backlog of errors from the previous months of the year‐long reporting period. Participants were also asked to complete an evaluation survey of the new system.

What this study adds

It is feasible to implement a large scale web‐based medication error reporting system in long‐term care facilities.

Such a system can collect detailed information on the characteristics of medication errors.

Facilities using the system report that it will help them identify areas for training and improvement, improve patient safety and reduce medication errors.

In recruiting nursing homes for this study we were interested in working with facilities that had a desire and willingness to help test the new system; therefore, we decided to issue an invitation and recruit volunteers rather than select a random sample of study sites. A review of the first 25 responding sites showed a group relatively diverse in terms of size, geographical location and ownership characteristics, so a decision was made to select those sites. Table 1 provides a comparison of the key characteristics of the study and non‐study nursing homes, showing similarity in all categories.

Table 1 Comparison of key demographic characteristics of the study and non‐study nursing homes.

| Characteristic | Study nursing homes n = 25 | Non‐study nursing homes n = 364 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total beds | Median | 120 | 119.5 |

| Mean | 115 | 121.5 | |

| IQR | 88–136 | 96–140 | |

| Urban‐rural score* | Median | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Mean | 2.6 | 3.07 | |

| IQR | 1–4.2 | 1–4.2 | |

| For‐profit status (%) | 68 | 79.89 | |

| With chain ownership (%) | 72 | 73.91 | |

| Errors reported in previous year | Median | 22 | 22 |

| Mean | 29.9 | 42.2 | |

| IQR | 14–32 | 10–42 |

IQR, interquartile range.

*Based on the RUCA (rural‐urban commuting area) version 2.0 code definitions; score of 1–10.6, with 10.6 being most rural.

Study administration

At the start of the study, written training materials were mailed to participants, including login information and passwords. After 3 weeks, any nursing home that had not yet used the system was telephoned and encouraged to begin entering reports. Approximately mid‐way through the 4‐month study period participants were asked to complete an online evaluation survey of the new system, focusing on usability and the potential value to patient care.

Results

Rates of study completion and response to evaluation survey

Of the 25 participating nursing homes, 23 (92%) successfully entered error reports into the new system. Unexpected staff changes and illnesses prevented the remaining two sites from participating. The 23 nursing homes submitted a total of 631 error reports during the study period from 15 May 2006 to 30 September 2006. These reports included all errors that had occurred at their facility for the entire year, starting from 1 October 2005. These 631 reports contained information on 2731 discrete error instances because many errors were repeated multiple times before detection. Of the 23 nursing homes that actually used the system and submitted reports, 20 (86%) completed the evaluation survey.

Overview of medication errors reported

Table 2 shows the patient impact or outcomes of all errors, both for the number of reports and the total errors weighted by the number of times the error was repeated. Of the 631 errors reported during the study, 51 (8%) were classified as having a serious patient impact that required monitoring or intervention, or worse. Of these errors, one required a trip to the hospital emergency department and two incidents required intervention necessary to sustain life.

Table 2 Patient impact (outcome).

| Reports n (%) | Total errors weighted for repeats n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Incident had the capacity to cause error—potential error with no specific patient | 16 (3) | 87 (3) |

| Error or potential error occurred but did not reach patient | 64 (10) | 109 (4) |

| Error reached patient but did not cause harm (includes dose omissions with no negative | 500 (79) | 2311 (85) |

| effects) | ||

| Error required monitoring or intervention to preclude harm | 46 (7) | 217 (8) |

| Error contributed to, or resulted in, temporary harm to the patient and required | 2 (<1) | 2 (<1) |

| intervention | ||

| Error contributed to, or resulted in, temporary harm requiring transfer to an emergency | 1 (<1) | 3 (<1) |

| department | ||

| Error contributed to, or resulted in, permanent patient harm | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Error required intervention necessary to sustain life | 2 (<1) | 2 (<1) |

| Error my have contributed to, or resulted in, the patient's death | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Total | 631 (100) | 2731 (100) |

The six most common error types were dose omission (203, 32%), overdose (91, 14%), underdose (43, 7%), wrong patient (38, 6%), wrong product (38, 6%), and wrong strength (38, 6%). Of the incidents with the most serious patient impact, 12 (24%) were wrong patient errors, 11 (22%) were dose omissions and 10 (20%) were overdoses. The most commonly reported cause was basic human error (402, 48%), followed by transcription error (152, 18%), and poor communication (34, 4%). Most errors occurred during administration (296, 47%) or documentation (237, 38%), with a smaller number related to dispensing (72, 11%), monitoring (16, 3%), and prescribing (10, 2%). Of the errors with the most serious patient impact, 67% (34) first occurred in the administering phase, 22% (11) in the documenting phase and 8% (4) in the pharmacy dispensing phase.

Licensed practical nurses were the most common category of primary personnel implicated in the error (372, 59%), followed by registered nurses (136, 22%), support personnel (70, 11%), pharmacists (37, 6%), and medication aides (8, 1%). Physicians were primarily responsible for seven errors (7, 1%). Of the primary personnel implicated in the error, 26 (4%) were temporary or contract personnel, 581 (92%) were permanent regular staff, and 24 (4%) had unreported employment status.

Approximately 87% (556) of errors had no observed negative medical effect on the patient. When an effect was observed, these included inadequate effect of medication (36, 6%), change in blood pressure (10, 2%), change in blood sugar (6, 1%), excessive side effects (6, 1%), somnolence (5, 1%), cognitive change (3, <1%), nausea or vomiting (3, <1%), oedema (1, <1%), fall (1, <1%), headache (1, <1%), respiratory distress (1, <1%) and constipation or diarrhoea (2, <1%).

When looking at the specific medications involved in errors, seven drugs were involved in almost a third (175, 28%) of all errors: lorazepam (40, 6%), oxycodone (29, 5%), warfarin (25, 4%), furosemide (21, 3%), hydrocodone (21, 3%), insulin (20, 3%) and fentanyl (19, 3%). One major reason for developing an individual incident error reporting system was to be able to link specific drugs to specific types of errors. Of particular interest are the drugs associated with two errors with the potential for serious patient harm—wrong patient and wrong product errors. In looking at the drugs associated with wrong patient errors in the results, many have the potential to cause major harm when given to the wrong patient. The drugs implicated in the wrong patient category included warfarin, insulin, oxycodone, hydrocodone, lorazepam, furosemide, metformin and phenytoin sodium. In looking at drugs associated with wrong product errors, some of the drugs mistakenly given were clonazepam instead of morphine, lidocaine instead of sterile water, clonazepam instead of clonidine and morphine instead of oxycodone.

We were able to pinpoint the exact drugs involved in name confusion errors. Examples of such errors include sulfadiazine instead of sulfasalazine, Lovenox (low molecular weight heparin) instead of lovastatin, lorazepam instead of alprazolam, clonazepam instead of lorazepam, and acetaminophen (paracetamol) hydrocodone bitartrate instead of acetaminophen (paracetamol) oxycodone hydrochloride.

Evaluation survey

The 20 participants (86% response rate) who completed the evaluation survey rated the system positively. They thought the new system was easy to use, would improve the accuracy and completeness of their reporting, would help identify areas for improvement and training, and would help reduce errors and improve patient medication safety. All evaluation items had a mean score of greater than 3 on a 4‐point scale (table 3).

Table 3 Evaluation survey results—respondents' level of agreement with new system objectives being met.

| Mean (SD) score* | |

|---|---|

| The system is easier overall than the annual summary report system | 3.8 (0.4) |

| The system will take less time than the annual summary report system | 3.7 (0.5) |

| The instructions are easy to follow | 3.6 (0.5) |

| The system is easier for staff than the annual summary report system | 3.5 (0.5) |

| The system will increase the completeness of our error reporting | 3.5 (0.5) |

| The system is easier to incorporate into our workflow | 3.5 (0.6) |

| The system is easy to use | 3.4 (0.5) |

| The system's summary reports will help identify areas for training and improvement | 3.4 (0.5) |

| Using the new system will increase the level of detail of error reporting | 3.3 (0.6) |

| Using the new system will improve the overall medication error reporting process | 3.2 (0.6) |

| Using the new system will increase the accuracy of our error reporting | 3.2 (0.5) |

| Using the new system will help improve patient safety and help avoid medication errors | 3.1 (0.6) |

*Respondents rated each item from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree).

Discussion

We found that the nursing homes participating in the present study were able to successfully use a web‐based reporting system, and they were able to do so easily, with no special training. Although the study nursing homes were volunteers, and not selected by random sampling, as a group they closely matched the state's non‐study nursing homes on key characteristics. The results of the participants' evaluation of the new system were positive with regard to the objectives set for the system. The users found the system easy to use and thought it would help identify areas for training and improvement, improve patient safety and help reduce errors.

Several factors may have contributed to the ready acceptance and use of this reporting system. Although reporting of medication errors is now mandatory in nursing homes in North Carolina, and the reporting effort was certainly enhanced by this requirement, this alone does not fully explain the system's success. As noted in the quality improvement literature, even when the requirement to report is mandatory, without an audit function or other ability to check, reporting is essentially voluntary. Perhaps one of the main factors contributing to our high participation rates was that in our communication and training with the sites we emphasised that the purpose of error reporting was for learning and quality improvement purposes only, and not for punitive or safety ranking purposes. We also guaranteed confidentiality with regard to both individual error reports and site aggregate error data. Some participants appreciated that the reporting system did not unduly focus on nurse medication administration errors, but instead looked at errors across all five phases of medication care with many staff categories including doctors and pharmacists. Another factor contributing to our overall success was that the system enjoyed the full collaboration with and endorsement of the state agencies with long‐term care oversight responsibility and the private associations that represent the interests of nursing homes in the state.

As a quality improvement tool, a widely implemented standardised web‐based system offers major advantages over a paper‐based system or standalone internalised reporting systems. The large scale, web‐based system allows for greater power to detect problems by relying on real‐time experiences of similar facilities.24 Looking across nursing homes, for example, problems with specific medication name confusions or administration procedures may be identified and warnings sent out communicating risk.

Limitations of the study

While this study has shown that is it feasible for nursing homes to use a web‐based reporting system, we have not shown yet that such a system actually reduces medication errors. Also, we cannot be certain of the accuracy or completeness of reported errors—a problem consistent with any spontaneous reporting system.

Future work

In the light of the highly positive outcomes of the initial implementation study, a decision was made to make the new system available to all North Carolina nursing homes from 1 October 2006, with the goal of moving all of the approximately 400 nursing homes in the state over to the new system as quickly as possible. In the interest of improving feedback to nursing homes, the next version of the system will include improved summary reporting capabilities in the form of charts and graphs, customisable for each site.

A plan is also underway to disseminate a quarterly bulletin alerting all nursing homes to information that may be helpful, such as warnings of specific medication name confusion issues reported by participants, and quality improvement strategies that facilities have found successful and wish to share with other sites.

We conclude that it is feasible to use an error reporting system as part of an overall strategy for reducing errors in long‐term care, and that such a system can supply valuable information for improving medication safety.

Footnotes

This work was funded by the North Carolina Division of Facility Services, a US state organisation responsible for licensing nursing homes.

Competing interests: All authors declare that they have no competing interests and therefore nothing to declare.

This study was determined to be exempt from review by the UNC‐Chapel Hill Internal Review Board. The IRB project number is 03‐2169.

References

- 1.Gurwitz J H, Field T S, Avorn J.et al Incidence and preventability of adverse drug events in nursing homes. Am J Med 200010987–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gurwitz J H, Field T S, Judge J.et al The incidence of adverse drug events in two large academic long‐term care facilities. Am J Med 2005118251–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Institute of Medicine Institute of Medicine report: preventing medication errors. Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2006

- 4.Ribbe M W, Ljunggren G, Steel K.et al Nursing homes in 10 nations: a comparison between countries and settings. Age Ageing 199726(Suppl 2)3–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bates D W, Gawande A A. Improving safety with information technology. N Engl J Med 20033482526–2534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bates D W, Evans R S, Murff H.et al Detecting adverse events using information technology. J Am Med Inform Assoc 200310115–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Poon E G, Jha A K, Christino M.et al Assessing the level of healthcare information technology adoption in the United States: a snapshot. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 200661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Billings C E. Appendix B. Incident reporting systems in medicine and experience with the aviation safety reporting system. In: Cook RI, Woods DD, Miller C, eds. A tale of two stories: contrasting views of patient safety. Chicago: National Patient Safety Foundation, 1998. Available at http://www.npsf.org/exec/billings.html

- 9.Flynn E A, Barker K N, Pepper G A.et al Comparison of methods for detecting medication errors in 36 hospitals and skilled‐nursing facilities. Am J Health Syst Pharm 200259436–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jha A K, Kuperman G J, Teich J M.et al Identifying adverse drug events: development of a computer‐based monitor and comparison with chart review and stimulated voluntary report. J Am Med Inform Assoc 19985305–314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cullen D J, Bates D W, Small S D.et al The incident reporting system does not detect adverse drug events: a problem for quality improvement. Jt Comm J Qual Improv 199521541–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leape L L. Reporting of adverse events. N Engl J Med 20023471633–1638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barach P. The end of the beginning: lessons learned from the patient safety movement. J Leg Med 2003247–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barach P, Small S D. Reporting and preventing medical mishaps: lessons from non‐medical near miss reporting systems. BMJ 2000320759–763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mekhjian H S, Bentley T D, Ahmad A.et al Development of a web‐based event reporting system in an academic environment. J Am Med Inform Assoc 20041111–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tuttle D, Holloway R, Baird T.et al Electronic reporting to improve patient safety. Qual Saf Health Care 200413281–286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kivlahan C, Sangster W, Nelson K.et al Developing a comprehensive electronic adverse event reporting system in an academic health center. Jt Comm J Qual Improv 200228583–594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rudman W, Bailey J, Hope C.et al The impact of a web‐based reporting system on the collection of medication error occurrence data. AHRQ Adv Patient Saf 20053195–205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Savage S W, Schneider P J, Pedersen C A. Utility of an online medication‐error‐reporting system. Am J Health Syst Pharm 2005622265–2270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pierson S. A web‐based medication error reporting system for nursing homes: pilot study evaluation [Master's thesis]. Columbia, MO: University of Missouri, Columbia, 2006

- 21.Greene S, Williams C, Hansen R.et al Medication errors in nursing homes. J Patient Saf 20051181–189. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hansen R A, Greene S B, Williams C E.et al Types of medication errors in North Carolina nursing homes: a target for quality improvement. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother 2006452–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Uribe C L, Schweikhart S B, Pathak D S.et al Perceived barriers to medical‐error reporting: an exploratory investigation. J Healthc Manag 200247263–279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cousins D D. Developing a uniform reporting system for preventable adverse drug events. Clin Ther 199820(Suppl C)C45–C58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]