Abstract

Background

Step exercise has been promoted as a low impact physical activity recommended for the improvement of cardiorespiratory and muscular fitness. This recreational activity might also be recommended to improve bone health since mechanical load plays an important role in the normal development of the skeleton.

Methods

Our main purpose was to characterised 100 step sessions and to calculated osteogenic index (OI) according to Turner and Robling: OI (one session) = peak ground reaction force(BW)*ln(number of loading cycles+1).

Results

Main results (mean±SD) were as follows: OI was 12.0±0.8; peak ground reaction force (GRF) was 1.40±0.10 times body weight (BW); session duration was 38.6±8.3 min; stepping rate was 134.6±4.7 beats per minute (bpm); the movements performed most often were marching, knee hop, side leg, L step, and over the top; and the number of loading cycles was 4194.1±1055.2. OI and GRF increased significantly when stepping rate was higher than 135 bpm. This stepping rate might be used as a reference for higher intensity classes. A frequency of two to three sessions per week of step exercise is recommended.

Conclusions

Despite the benefits that have been stated when step classes are structured correctly and adapted to the participants, further research is needed concerning biomechanical load, exercise prescription, and injury prevention.

Keywords: ground reaction forces, osteogenic index, step exercise, step pattern, stepping rate

Step exercise has been promoted as a low impact physical activity recommended for the improvement of cardiorespiratory1 and muscular fitness. The main goals of performing step‐on (forward‐ascending) and step‐off (backward‐descending) movements combined with marching, dancing, jogging, and jumping exercises, as part of choreographed sequences using a step bench 10–25 cm high, are to obtain metabolic and mechanical benefits for health and fitness. Step movements use right or left leading legs, single or alternate leading steps, and propulsion or non‐propulsion steps. Different choreographic patterns determine exercise intensity. Care must be taken in relation to the different movements chosen by instructors in each session and the mechanical load selected to provide a safe and effective exercise program. Previous studies have shown that biomechanical intensity is related to bench height and stepping rate.2,3 The osteogenic potential of physical activity can be improved by correctly structuring exercise sessions and defining the rate and magnitude of skeletal loading. External loads produce internal forces which constitute the mechanical load which is related to the osteogenic potential of physical activity. On the other hand, mechanical load may also be implicated in musculoskeletal injuries to the knee and ankle. Our major concern is how to best exercise while maintaining safe levels of mechanical load. The characterisation of stepping exercise requires the study of a large variety of movements with different motor patterns.

It is widely accepted that physical exercise increases and maintains bone mass and strengthens bone. Also, vigorous exercise during growth and young adulthood may well reduce fracture risk in later decades.4,5 However, there is no clear consensus on the best exercises and how often one should exercise. During exercise ground reaction forces (GRF) and internal forces are imposed on the skeleton. It is thought that bones respond to the strains imposed by these forces. Dynamic and high magnitude loading elicits a greater strain rate in bones and is known to be effective for anabolic loading.6 These forces are created during movement by muscle contractions and by impact with external objects, such as the ground in walking.7 It has been reported that mechanical loading generated by physical activity levels leads to improvements in skeletal development, mainly because weight bearing during exercise plays an important role in improving the mechanical properties of bone.8 When new forces or loads alter the normal daily pattern of bone bending and strain, the bone adapts by increasing formation that in turn increases mass, size, and moment of inertia to resist the altered bending.9 Huang et al10 concluded that different modes of exercise may benefit bone mechanical properties in different ways. Turner and Robling4 reported that load induced bone formation was improved by periods of rest. They also reported that as these no‐loading periods were lengthened, bone formation was further enhanced, and after 24 h of rest, 98% of bone mechanosensitivity was restored. Consequently, the osteogenic response to exercise can be enhanced by regimens that incorporate periods of rest between short vigorous skeletal loading sessions. Prolonged loading repetitions can diminish the mechanosensitivity of bones, but increased intervals between loading might restore sensitivity.6 Turner and Robling5 demonstrated that the osteogenic potential of exercise was improved by increasing the rate and magnitude of skeletal loading and separating exercise into many short sessions. These authors developed a new measure of effectiveness for exercise protocols called the osteogenic index (OI) which depends on the exercise intensity (peak GRF) and desensitisation, allowing the estimation of bone formation. For instance, the weekly OI generated by 20 min walking, five days per week is OI(week) = 1.1 BW*ln(800 cycles+1)*5(days/week) = 36.8, assuming that a 20 min walk generates about 800 loading cycles to each leg and the peak load is 1.1 body weight (BW). Another example is the OI generated by one session of jumps with approximately 120 loading cycles and a peak load of 3 BW, resulting in OI(1 session/day) = 3 BW*ln(120 cycles+1)*1(day) = 14.4.

Table 2 Statistical analysis of 100 step exercise classes.

| Duration (min) | Minimum stepping rate (bpm) | Maximal stepping rate (bpm) | Mean stepping rate (bpm) | Loading cycles (n) | Step move‐ ments (n) | Non‐pro‐ pulsion move‐ ments (%) | Propulsion move‐ ments (%) | Peak GRF (BW) | Osteogenic index | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median | 38 | 130 | 138 | 135.4 | 4144 | 1392 | 80 | 20 | 1.42 | 11.8 |

| Min | 25 | 120 | 128 | 124.9 | 1874 | 624 | 48 | 0 | 1.26 | 10.3 |

| Max | 58 | 142 | 150 | 144.7 | 7250 | 2524 | 100 | 52 | 1.65 | 14.0 |

| Range | 33 | 22 | 22 | 19.8 | 5376 | 1900 | 52 | 52 | 0.39 | 3.7 |

| Mean | 38.6 | 130.6 | 138.3 | 134.6 | 4194.1 | 1422.6 | 79.4 | 20.6 | 1.40 | 12.0 |

| SD | 8.3 | 5 | 4.4 | 4.7 | 1055.2 | 384.5 | 10.5 | 10.5 | 0.10 | 0.8 |

Bone formation with exercise can be estimated using the OI, which depends on exercise intensity and degree of desensitisation.4 The study of GRF is quite common in sports biomechanics with most reports characterising sports movement using only the vertical maximal GRF in terms of body weight.1,2,11,12,13,14 Other studies maintain that the osteogenic effect of step exercise is related to mean GRF of twice the body weight (BW).15 During a step class, the repetition of movements induces GRF of low magnitude (1–2 BW) and high frequency (3900–4200 loading cycles in a 30 min session, using music with 130–140 bpm). Step classes involve different movements and a variety of motor patterns, so that the GRF produced during a session depends on the type and number of movements performed and must be determined accordingly.

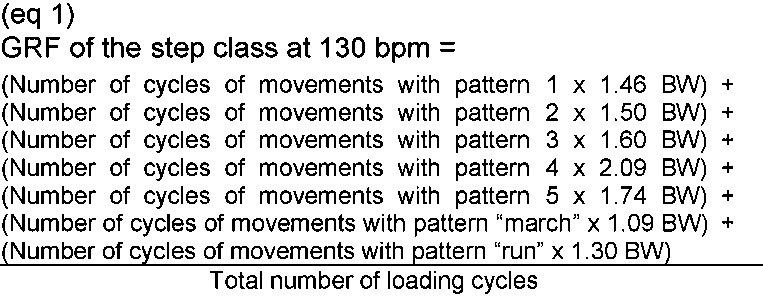

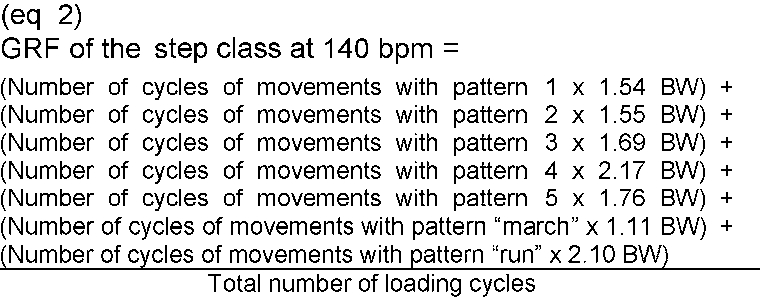

In previous studies using pressure insoles placed inside footwear,16 the maximal GRF of step movements were obtained at cadences of 130–140 bpm using a 15 cm high Step‐Reebok bench. Table 1 presents these values and also those for marching and running.17,18 The table also gives the number of loading cycles and the motor pattern of each movement. Each step corresponds to two, four, six, or eight loading cycles. The motor pattern of the basic step was defined as pattern 1, while pattern 2 refers to knee lift, pattern 3 to knee triple repeater, pattern 4 to run step, and pattern 5 to knee hop; the other patterns refer to marching and running.

Table 1 Maximal vertical ground reaction force in normalised body weight of 15 experienced subjects.

| GRF (in BW) at 130 bpm | GRF (in BW) at 140 bpm | Loading cycles | Motor pattern | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basic step | 1.46±0.30 | 1.54±0.34 | 2 for ascending and 2 for descending | Pattern 1: step on/step on/step off/step off |

| Knee lift step | 1.50±0.17 | 1.55±0.23 | 1 for ascending and 2 for descending | Pattern 2: step on/knee lift/step off/step off |

| Knee triple repeater | 1.60±0.22 | 1.69±0.24 | 1 for ascending and 2 for descending | Pattern 3: step on/triple knee lift repeater/step off/step off |

| Run step | 2.09±0.25 | 2.17±0.27 | 2 with propulsion for ascending and | Pattern 4: jump on/jump on/step off/step off |

| 2 for descending | ||||

| Knee hop step | 1.74±0.16 | 1.76±0.19 | 2 for ascending (1 with propulsion) | Pattern 5: step on/hop knee lift/step off/step off |

| and 2 for descending | ||||

| Marching | 1.09 | 1.11 | Continuous | Pattern “march”: continuous steps |

| Running | 1.30 | 2.10 | Continuous with propulsion | Pattern “run”: continuous steps with propulsion |

Our main purposes were to characterise 100 step sessions and to calculate the osteogenic index.4 In order to achieve this, we aimed in each class analysed to record the duration of the class in minutes, count the stepping rate, count the total number and types of movements performed, calculate the percentage of propulsion/non‐propulsion steps, calculate the number of loading cycles performed, determine the motor pattern of each movement performed, calculate the GRF of each class according to the patterns performed, calculate the osteogenic index, determine the descriptive statistics of these variables for the total number of classes, count the step patterns performed most often, analyse hypothesised differences between groups defined according to session duration, and analyse hypothesised differences between groups defined according to session stepping rate.

Methods

The osteogenic index defined by Turner and Robling4 needs the following variables for each exercise session: (1) peak vertical GRF (BW); (2) number of loading cycles that occur during the session; and (3) number of sessions. One step session per week was considered. The GRF and the number of loading cycles depend on the type and number of movements included in choreography, and on the duration and stepping rate. Thus, to obtain these variables, 100 step classes were analysed in order to calculate the osteogenic index of each one. More than 100 sessions were observed in 2005 by the same person who used a specific observation sheet to record session duration, speed, and choreographic movements. All instructors and subjects enrolled in these classes volunteered to participate in the study. The observer did not interfere at all in any class. This study was approved by the review committee of the Sport Sciences School of Rio Maior. Duration was controlled using a chronometer; each class had to have a minimal duration of 25 min to be considered in this study. The stepping rate was recorded every 5 min. The number of loading cycles was determined by stepping rate. The number and type of movements used during each class were counted and recorded. Each movement was part of a step pattern corresponding to a peak GRF, as calculated in previous studies using in‐shoe NOVEL‐PEDAR plantar pressure insoles with 99 sensors (table 1). Using the total number of step movements, a weighted average of the peak GRF of the session was determined using Excel as shown in eqs 1 and 2 (which were derived from table 1). The total number of step movements and the movements performed most often were recorded. Also, the percentage of non‐propulsion/propulsion movements was determined. The osteogenic index was calculated in Excel using the equation of Turner and Robling: OI(1 session/day) = peak GRF(BW)*ln(loading cycles+1).4

|

|

Median, minimal, maximal, range, mean, and standard deviation values for total session duration (min), minimum, maximal, and mean stepping rate used in sessions (bpm), number of loading cycles, number of step movements, percentage of non‐propulsion/propulsion movements observed in 100 sessions, as well as weighted peak GRF normalised in BW and osteogenic index were calculated. Kolmogorov‐Smirnov normality tests, one way ANOVA, and Tukey post hoc test were performed using SPSS 13.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL). The level of statistical significance was set at p⩽0.05.

Results

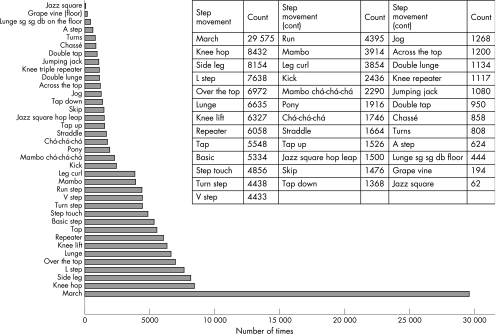

Table 2 indicates that the mean(±SD) number of loading cycles was 4194.1±1055.2 (range 1874–7250), the mean(±SD) number of movements was 1422.6±384.5 (range 624–2524), the mean(±SD) percentage of non‐propulsion movements was 79.4±10.5% (range 48–100%), and the mean(±SD) percentage of propulsion movements was 20.6±10.5% (range 0–52%). Step movements and frequency performed are presented in fig 1. Marching was the exercise performed most often in the 100 sessions (29 575 times); the four step movements performed most often were knee hop (variant of knee lift with propulsion), side leg (variant of knee lift), L step (variant of knee lift), and over the top (variant of basic step) which were performed 8432, 8154, 7638, and 6972 times, respectively.

Figure 1 Step movements performed most often in 100 step sessions.

Interestingly, the majority of participants were female. In all classes most of the participants used a 15 cm high bench and hand weights were not used. Mean(±SD) magnitude of peak vertical GRF was 1.40±0.10 BW (range 1.26–1.65), according to the motor patterns performed, and mean(±SD) osteogenic index was 12.0±0.8 (10.3–14.0).

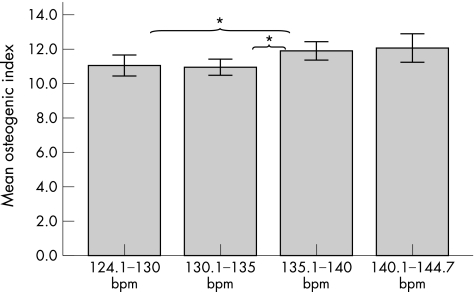

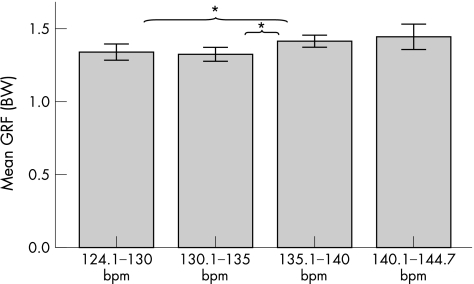

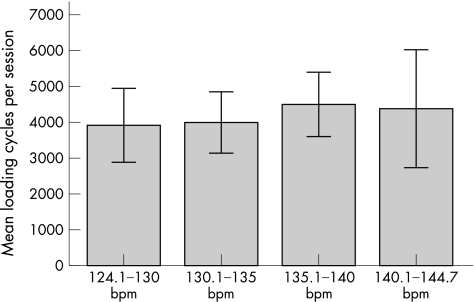

For better analysis in practical terms, step sessions were divided into four groups according to stepping rate as follows: (1) 124.1–130 bpm; (2) 130.1–135 bpm; (3) 135.1–140 bpm; and (4) 140.1–144.7 bpm. Mean values (±SD) of number of loading cycles, maximal vertical GRF, osteogenic index, and duration for these four groups are presented in table 3.

Table 3 Mean values and standard deviation of number of loading cycles.

| Group defined for stepping rate (bpm) | n | Osteogenic index | GRF (in BW) | Loading cycles | Duration (min) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) 124.1–130 bpm | 26 | 11.65±0.87 | 1.39±0.09 | 4362.9±1020.3 | 43.2±7.6 |

| (2) 130.1–135 bpm | 32 | 11.76±0.73 | 1.42±0.08 | 4031.3±1032.6 | 36.9±8.3 |

| (3) 135.1–140 bpm | 37 | 12.31±0.76 | 1.48±0.09 | 4174.8±1016.9 | 37.0±7.4 |

| (4) 140.1–144.7 bpm | 5 | 12.08±0.88 | 1.44±0.09 | 4501.4±1720.6 | 37.0±11.5 |

Maximal vertical ground reaction forces (GRF) in normalised body weight (BW), osteogenic index, and duration for the four groups defined by stepping rate.

A one way ANOVA was conducted with a Tukey post hoc test for each variable in order to compare them among these groups.

The mean osteogenic index was compared among these groups (fig 2). Osteogenic index increases significantly when stepping rate is higher than 135 bpm, being significantly different among the stepping rate groups (F(3,36) = 8.132; p = 0.000). These differences were found between the 124.1–130 bpm and 135.1–140 bpm groups (p = 0.001), and between the 130.1–135 bpm and 135.1–140 bpm groups (p = 0.001).

Figure 2 Mean osteogenic index of step exercise sessions (n = 100) depending on stepping rate (in beats per minute). Error bars: 95% CI. *p<0.05.

Mean peak vertical GRF in BW was compared among these groups (fig 3). Peak GRF increases significantly when stepping rate is higher than 135 bpm, being significantly different among stepping rate groups (F(3,36) = 10.727; p = 0.000). Post hoc tests indicated that these differences were found between the 124.1–130 bpm and 135.1–140 bpm groups (p = 0.001), and between the 130.1–135 bpm and 135.1–140 bpm groups (p = 0.000).

Figure 3 Mean peak vertical ground reaction force (GRF) normalised in body weight (BW) of step exercise sessions (n = 100) depending on stepping rate (in beats per minute). Error bars: 95% CI. *p<0.05.

The mean number of loading cycles per session was compared among these groups (fig 4). The number of loading cycles was higher in the two groups with faster cadence. However, no significant differences were found among groups regarding the number of loading cycles (F(3,36) = 0.574; p = 0.633). Mean session duration was similar among groups with no significant differences between them (F(3,36) = 0.836; p = 0.477).

Figure 4 Mean number of loading cycles per session of step exercise (n = 100) depending on stepping rate (in beats per minute). Error bars: 95% CI.

For better analysis in practical terms, step sessions were divided into groups according to duration as follows: (1) 25–30 min; (2) 30.1–35 min; (3) 35.1–40 min; (4) 40.1–45 min; and (5) 45.1–58 min. Mean values and standard deviation of OI, maximal vertical GRF in BW, number of loading cycles, and stepping rate for these five groups are presented in table 4.

Table 4 Number of loading cycles, maximal vertical GRF in normalised BW weight, osteogenic index, and stepping rate for the five groups defined for session duration.

| Groups defined for duration (min) | n | Osteogenic index | GRF (in BW) | Loading cycles | Stepping rate (bpm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) 25–30 min | 23 | 11.88±0.61 | 1.48±0.07 | 3151.6±760.8 | 136.0±4.5 |

| (2) 30.1–35 min | 22 | 11.58±0.62 | 1.41±0.07 | 3774.7±445.1 | 135.3±3.7 |

| (3) 35.1–40 min | 20 | 12.28±0.96 | 1.47±0.10 | 4355.5±824.3 | 135.2±4.9 |

| (4) 40.1–45 min | 17 | 11.73±0.89 | 1.39±0.10 | 4727.7±839.3 | 132.6±5.5 |

| (5) 45.1–58 min | 18 | 12.34±0.84 | 1.44±0.09 | 5355.6±791.1 | 133.2±4.5 |

Values are mean±SD. BW, body weight.

A one way ANOVA was conducted with a Tukey post hoc test in order to compare variables among these groups.

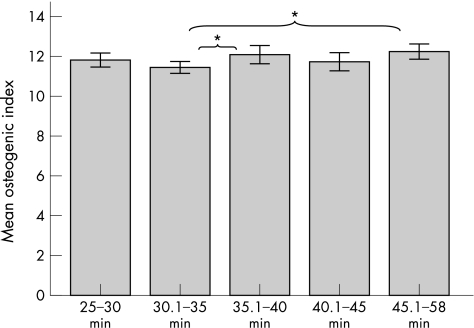

The mean osteogenic index was compared among these groups (fig 5), being significantly different among the session duration groups (F(4,95) = 3.616; p = 0.009). These differences were found between the 30.1–35 min and 35.1–40 min groups (p = 0.036), and between the 30.1–35 min and 45.1–58 min groups (p = 0.024).

Figure 5 Mean osteogenic index of step exercise sessions (n = 100) depending on session duration (in minutes). Error bars: 95% CI. *p<0.05.

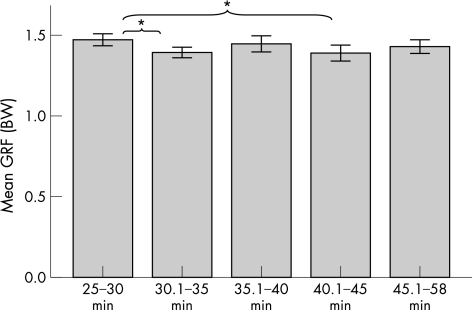

The mean peak vertical GRF in BW was compared among these groups (fig 6). There was a significant difference among session duration groups (F(4,95) = 4.105; p = 0.004) on the dependent variable GRF. These differences were found between the 25–30 min and 30.1–35 min groups (p = 0.036), and between the 25–30 min and 40.1–45 min groups (p = 0.012).

Figure 6 Mean peak vertical ground reaction forces (GRF) normalised in body weight (BW) of step exercise sessions (n = 100) depending on session duration (in minutes). Error bars: 95% CI. *p<0.05.

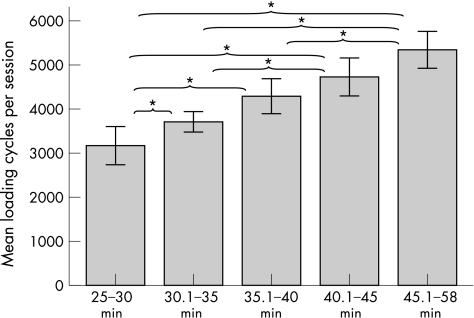

The mean number of loading cycles per session was compared among these groups (fig 7). There was a significant difference among session duration groups (F(4,95) = 26.872; p = 0.000) on the dependent variable number of loading cycles, which increases progressively, as would be expected. These differences were found between the 25–30 min and 30.1–35 min groups (p = 0.044), between the 25–30 min and 35.1–40 min groups (p = 0.000), between the 25–30 min and 40.1–45 min groups (p = 0.000), between the 25–30 min and 45.1–58 min groups (p = 0.000), between the 30.1–35 min and 40.1–45 min groups (p = 0.001), between the 30.1–35 min and 45.1–58 min groups (p = 0.000), and between 35.1–40 min and 45.1–58 min groups (p = 0.001).

Figure 7 Mean number of loading cycles in step exercise sessions (n = 100) depending on session duration (in minutes). Error bars: 95% CI. *p<0.05.

The mean stepping rate was compared among these groups. There was no significant difference among the five session duration groups (F(4,95) = 2.011; p = 0.099) on the dependent variable stepping rate. Stepping rate was similar among groups.

Discussion

This may be the first study to characterise step exercise sessions as they really happen in practice, and to calculate the osteogenic index. Step exercise is far from being defined by basic steps at 122 bpm as initially proposed by its creators. The mean and standard deviation values for stepping rate were 134.6±4.7 bpm, ranging from 120 to 150 bpm, which means that cadence varied from slow to fast. Step sessions have many different easy and complex movement patterns. Thirty seven different movement patterns were identified, which produce different biomechanical loads. Most of the participants used step benches 15 cm high, as expected. However, as discussed in a previous study,2 a 10 cm step bench might be more appropriate depending on age, expertise level, and choreography (for example, for the elderly, beginners, very young people, pregnant women, and those with previous knee injury or undergoing rehabilitation). The three main determinants of exercise intensity that can be manipulated by instructors are bench height, stepping rate, and choreography. Thus, further research concerning these variables is essential.

The mean(±SD) weighted peak ground reaction force normalised to body weight was 1.4±0.1 BW, ranging from 1.26 to 1.65 BW, according to the motor patterns performed. Based upon the literature and preliminary laboratory studies, high skeletal loading intensity has been defined as GRF of greater than 4 BW, moderate intensity as 2–4 BW, and low intensity as less than 2 BW.15,19 However, further research is needed concerning the GRF of different step movements performed at different cadences. Nevertheless, the result of the loading on the body depends on three factors: the magnitude of the force, the rate at which the force is applied, and the repetition of load application.20

Stepping rate is one determinant of mechanical intensity. OI and GRF increase significantly when stepping rate is higher than 135 bpm. This stepping rate might be used as a reference for higher intensity classes. Also, OI, GRF, and loading cycles are higher in classes where cadence is faster. Session duration also seems to have an influence on these variables, especially the number of loading cycles, as expected, but seems to have no influence on stepping rate, which means that a 30 min workout using fast cadences might induce similar amounts of loading as longer sessions.

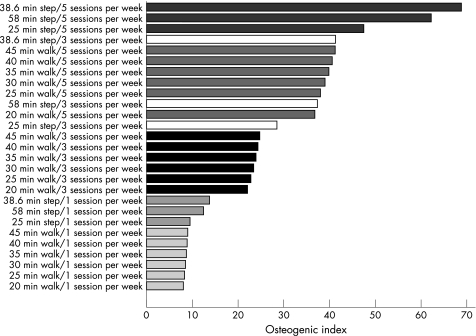

According to Turner and Robling,4 if the osteogenic response to exercise is enhanced by regimens that incorporate periods of rest between short vigorous skeletal loading sessions, a frequency of two to three sessions per week of step exercise is sufficient. Despite the benefits claimed for step classes correctly structured and adapted to participants, further research is needed regarding exercise prescription and injury prevention. Additional study is also required concerning the biomechanical load of this activity, as there is no information concerning GRF for many of the stepping patterns and stepping rates.

The OI can also be used to compare different physical activities. Using the same calculations, a simulation was done for one, three, and five sessions of walking and stepping per week, as presented in fig 8. The example given by Turner and Robling4 was used for walking. As shown in the figure, step exercise has a higher OI than walking, meaning that stepping exercise of the same intensity (duration and frequency) as walking might be more effective in terms of OI. Other exercises could be compared when there is more information on their physical activity characteristics (number of loading cycles) and biomechanical loading (GRF).

Figure 8 Osteogenic index calculated for step exercise and walking depending on session duration (in minutes) and frequency (number of sessions per week).

The present study should be replicated in the future, when more information becomes available concerning the GRF of different movement patterns and stepping rates. Also, a worksheet might be developed in order to quickly estimate the osteogenic potential of exercise.

Conclusions

The Turner and Robling4 osteogenic index might be useful for better understanding of the positive association between exercise and bone health. OI depends on the GRF of activities which in turn depend on the types of movements and stepping rate. The mean(±SD) osteogenic index of 100 step classes was 12.0±0.8 (range 10.3–14.0), the stepping rate was 134.6±4.7 bpm (120–150 bpm), and the total number of loading cycles was 4194.1±1055.2 (which might help to meet the recommended 10 000 steps a day).21 OI and GRF increase significantly when stepping rate is higher than 135 bpm. In practical terms, step exercise seems to provide a healthy mechanical stimulus, if safely performed, with mechanical load falling between that provided by walking and running. Stepping rate is a very important determinant of mechanical intensity and should be carefully chosen by instructors according to the participants' level of expertise. Despite the stated benefits when step classes are correctly structured and adapted to the participants' level of expertise, further research is needed concerning biomechanical loading to improve exercise prescription and prevent injury.

What is already known on this topic

Step exercise is a low impact physical activity recommended for the improvement of cardiorespiratory and muscular fitness

The mechanical loads experienced during step exercise may improve bone health

A measure of the effectiveness of exercise protocols is provided by the osteogenic index which estimates bone formation according to exercise intensity and desensitisation

What this study adds

A hundred step exercise sessions have been characterised and their osteogenic index calculated

Differences were found in osteogenic index depending on session duration and stepping rate

The osteogenic indices of step and walking exercises have been compared.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank to all instructors and participants of the sessions observed during this study. The authors wish to thank David Catela, MSc (Sport Sciences School of Rio Maior) for his contributions to this manuscript.

Abbreviations

BW - body weight

GRF - ground reaction force

OI - osteogenic index

Footnotes

There are no competing interests

References

- 1.Scharff‐Olson M, Williford H N, Blessing D L.et al Vertical impact forces during bench‐step aerobics: exercise rate and experience. Percept Mot Skills 199784267–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Santos‐Rocha R, Veloso A, Santos H.et al Ground reaction forces of step exercise depending on step frequency and bench height. In: Gianikellis K, ed. Scientific Proceedings of the XXth International Symposium on Biomechanics in Sports. International Society of Biomechanics in Sports 2002156–158.

- 3.Santos‐Rocha R, Pezarat‐Correia P, Franco S.et al Análise da participação muscular no passo básico de step: efeito da velocidade da música e da altura da plataforma (in Portuguese). Revista Brasileira de Biomecânica—Brazilian Journal of Biomechanics 20045(8)5–12. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Turner C H, Robling A G. Designing exercise regimens to increase bone strength. Exerc Sport Sci Rev 200331(1)45–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Turner C H, Robling A G. Exercises for improving bone strength. Br J Sports Med 200539188–189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Umemura Y, Sogo N, Honda A. Effects of intervals between jumps or bouts on osteogenic response to loading. J Appl Physiol 2002931345–1348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cullen D M, Smith R T, Akhter M P. Bone‐loading response varies with strain magnitude and cycle number. J Appl Physiol 2001911971–1976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carter D R. Mechanical loading history and skeletal biology. J Biomech 1987201095–1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cullen D M, Smith R T, Akhter M P. Time course for bone formation with long‐term external mechanical loading. J Appl Physiol 2000881943–1948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang T H, Lin S C, Chang F L.et al Effects of different exercise modes on mineralization, structure, and biomechanical properties of growing bone. J Appl Physiol 200395300–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Francis P, Francis L, Miller G.et al Effects of choreography, step height, fatigue and gender of step training. Med Sci Sports Exerc 199224(5)abstract 69 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hecko K, Finch A. Effects of prolonged bench stepping on impact forces. In: Abrantes J, ed. Proceedings of the XIV International Symposium on Biomechanics in Sports. Lisbon: Edições FMH, 1996464–466.

- 13.Bezner S A, Chinworth S A, Drewlinger D M.et alStep aerobics: a kinematic and kinetic analysis. Denton, TX: Texas Women's University, 1996252–254.

- 14.Maybury M C, Waterfield J. An investigation into the relationship between step height and GRF in step exercise: a pilot study. Br J Sports Med 199731109–113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shaw J M, Witzke K A, Winters K M. Exercise for skeletal health and osteoporosis prevention. In: M Hauber, ed. ACSM's resource manual for guidelines for exercise testing and prescription. 4th ed. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins, 2001, ch 34

- 16.Santos‐Rocha R, Veloso A. Plantar pressure and peak GRF in step exercise: comparison of field and laboratory assessment. In: Rodrigues H, Cerrolaza M, Doblaré M, et al eds. Proceedings of the ICCB 2005—II International Conference on Computational Bioengineering. Vol 2. Lisbon: IST Press, 2005885–894.

- 17.Ricard M D, Veatch S. Effect of running speed and aerobic dance jump height on vertical GRF. J Appl Biomech 19941014–27. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ribeiro J K, Mota C B. Comportamento da força de reacção do solo durante a realização da marcha na ginástica de academia (in Portuguese). Revista Brasileira de Biomecânica—Brazilian Journal of Biomechanics 20045(8)49–55. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Witzke K A, Snow C M. Effects of plyometric jump training on bone mass in adolescent girls. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2000321051–1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hamill J, Caldwell G E. Mechanical load on the body. In: M Hauber, ed. ACSM's resource manual for guidelines for exercise testing and prescription. 4th ed. Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins, 2001, ch 11

- 21.Wilde B E, Sidman C L, Corbin C B. A 10,000‐step count as a physical target for sedentary women. Res Q Exerc Sport 200172(4)411–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]