Abstract

Objectives

To determine if, in the short term, acetic acid and dexamethasone iontophoresis combined with LowDye (low‐Dye) taping are effective in treating the symptoms of plantar fasciitis.

Methods

A double blinded, randomised, placebo controlled trial of 31 patients with medial calcaneal origin plantar fasciitis recruited from three sports medicine clinics. All subjects received six treatments of iontophoresis to the site of maximum tenderness on the plantar aspect of the foot over a period of two weeks, continuous LowDye taping during this time, and instructions on stretching exercises for the gastrocnemius/soleus. They received 0.4% dexamethasone, placebo (0.9% NaCl), or 5% acetic acid. Stiffness and pain were recorded at the initial session, the end of six treatments, and the follow up at four weeks.

Results

Data for 42 feet from 31 subjects were used in the study. After the treatment phase, all groups showed significant improvements in morning pain, average pain, and morning stiffness. However for morning pain, the acetic acid/taping group showed a significantly greater improvement than the dexamethasone/taping intervention. At the follow up, the treatment effect of acetic acid/taping and dexamethasone/taping remained significant for symptoms of pain. In contrast, only acetic acid maintained treatment effect for stiffness symptoms compared with placebo (p = 0.031) and dexamethasone.

Conclusions

Six treatments of acetic acid iontophoresis combined with taping gave greater relief from stiffness symptoms than, and equivalent relief from pain symptoms to, treatment with dexamethasone/taping. For the best clinical results at four weeks, taping combined with acetic acid is the preferred treatment option compared with taping combined with dexamethasone or saline iontophoresis.

Keywords: iontophoresis, plantar fasciitis, randomised controlled trial, LowDye taping, foot

Plantar fasciitis (PF) causes pain and stiffness in the heel and medial arch of the plantar surface of the foot and can interfere considerably with activities of daily living.1,2 It is common in the community and prevalent among those participating in running sports.3

Patients with PF report pain and/or stiffness localised to their heel which may extend distally to the arch of the foot.4 The typical patient describes symptoms during the first steps after rising in the morning.5 In most patients these symptoms vary in intensity and may settle or resolve after a variable period from a few steps to a few hours. In most cases, symptoms then increase as the day progresses.3,6,7 On palpation of the heel, tenderness is focal and localised to the medial calcaneal origin of the plantar fascia.3

Various treatment strategies, including orthoses,7,8,9,10 stretching,11,12,13,14,15 taping,10,16 extracorporeal shock wave therapy,17,18 laser therapy,19 and drug therapy in the form of systemic medication,11 percutaneous injection20,21,22, and topical application,23,24 have been investigated and have shown variable clinical benefit.

Two studies have shown clinically relevant improvements in PF symptoms using iontophoresis of dexamethasone23 and acetic acid.24 Non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs have been trialled,25 but did not show clinically significant effects.

LowDye (low‐Dye) taping26 supports the longitudinal arch of the foot. It has been shown to significantly reduce peak plantar pressures of normal feet during gait, especially the peak plantar pressure in the medial midfoot,16,27 so it might be expected to play a role in the management of PF. There are no reports in the literature of the use or efficacy of LowDye taping in the treatment of PF symptoms. HighDye taping has been shown to reduce rear foot eversion when walking but not LowDye taping.28 One limitation of long term taping is that there is potential for skin breakdown, and therefore it may be considered only as a short term management option usually combined with adjunct therapies.

No studies have examined how taping interacts with drug therapy during short term treatment of PF. The purpose of this study was to determine the short term efficacy of iontophoresis of acetic acid and dexamethasone combined with LowDye taping support.

Methods

Subjects

Subjects were recruited from three sports medicine clinics over one year. They provided informed consent as approved by the institutional human research ethics committee. Patients who met the diagnostic criteria were referred for plain non‐weight bearing radiographs of the foot and diagnostic ultrasound.

Subjects were included in the study if they fulfilled the following criteria:

aged 18–75 years, with heel pain for more than one month consistent with a history of PF

clinical diagnosis of PF of medial calcaneal origin based on patient history and physical examination

Subjects were excluded from the study if they had:

contraindications to dexamethasone, acetic acid, taping, or iontophoresis

specific pathology from trauma or other coexisting symptomatic foot pathology requiring treatment

calcaneal stress fracture, gout, bone tumour, osteomyelitis, diabetes

surgery for PF within the previous six months

new orthotics or corticosteroid treatment in the previous month

abnormal erythrocyte sedimentation rate or C reactive protein or HLA‐B27 positive

Interventions

Patients with PF were randomly assigned to one of three groups using computer generated block randomisation.

During the treatment phase, patients received six treatments of iontophoresis to the site of maximum tenderness on the plantar aspect of the foot. They received 0.4% dexamethasone, placebo (0.9% NaCl), or 5% acetic acid, delivered using the Phoresor II Iontophoresis Drug Delivery System (IOMED, Inc, Salt Lake City, Utah, USA). Current was applied up to 4 mA, and a total dose of 40 mA.min was delivered over a period of time determined by the patient's sensitivity. The six treatments were delivered on alternating days over a period of two weeks. At each treatment session, the LowDye taping was renewed, so that all subjects were continuously taped for two weeks. The subjects were reminded to perform two stretching exercises for the gastrocnemius/soleus muscle group for one minute twice daily.

The three drugs were dispensed into three identical colour coded bottles, and all randomisations were performed independently and concealed from the treating researcher and patient.

Before all iontophoretic treatments, the dorsum of the target foot was wiped with acetic acid (household vinegar) to mask the smell of the different solutions and minimise the chance of the patient and treating doctor being unblinded to the group allocation.

Measurements of primary outcomes were repeated at two week intervals (baseline, after treatment, and at follow up). At the completion of the treatment, the patient recorded which drug they thought had been used to determine if masking had been successful.

Outcome measures

Pain and stiffness were the two primary symptoms examined. These were assessed using a series of horizontal visual analogue scales where zero reflected the total absence of symptoms and 10 the worst imaginable pain or stiffness.

Pain visual analogue scale assessments included:

worst pain in the last two days

average pain in the last two days

pain on first rising on the morning of the assessment

residual pain (the pain remaining after the morning pain settles down with activity)

Stiffness visual analogue scale assessments were:

stiffness on first rising on the morning of the assessment

residual stiffness (the stiffness remaining after the morning stiffness settles down with activity)

We also recorded duration of morning stiffness (how long it took for the morning stiffness to settle down with activity).

Statistical analysis

Basic data were expressed as mean (SD). The raw data of the three repeated measures of the primary outcomes were converted into absolute change scores compared with the baseline score. Positive values reflected positive clinical effect, with the mean and 95% confidence interval (CI) shown in figures. Statistically significant changes were identified when the 95% CI did not include zero change.

Statistically significant differences between groups were determined using analysis of covariance with the initial baseline score as the covariant, and treatment groups as the between factor.29 Post hoc differences were determined using a Fisher's PLSD post hoc comparison. Processing was performed using StatView (SAS Institute Inc) and Excel (Microsoft Office). Statistical significance was set at p<0.05.

A χ2 contingency table was used to determine if subjects were able correctly determine better than chance their group allocation.

Results

Tables 1 and 2 show the basic characteristics of the subjects and the baseline scores for the primary symptoms respectively. There were no group differences at baseline across all variables (all values p>0.249).

Table 1 Basic characteristics of the three treatment groups.

| Placebo | Dexamethasone | Acetic acid | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No of patients | 10 | 11 | 10 | 31 |

| Bilateral | 2 | 4 | 5 | 11 |

| Age (years) | 52.2 (10.7) | 49.3 (13.3) | 52.0 (7.7) | 51.1 (10.6) |

| Duration of symptoms (months) | 7.5 (5.0) | 8.1 (7.5) | 18.6 (19.2) | 11.8 (13.5) |

| Sex (M:F) | 4:6 | 3:8 | 7:3 | 14:17 |

| Weight (kg) | 80.4 (18.0) | 79.2 (11.0) | 89.1 (17.4) | 83.4 (16.2) |

| Height (cm) | 167.3 (11.4) | 170.1 (8.5) | 169.9 (8.6) | 169.2 (9.3) |

| Body mass index | 28.6 (7.7) | 28.1 (4.0) | 31.2 (7.3) | 29.4 (6.6) |

Where applicable, values are mean (SD).

Table 2 Main outcome variables at baseline for the three treatment groups.

| Outcome variable | Placebo | Dexamethasone | Acetic acid | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of feet | 12 | 15 | 15 | 42 |

| Worst pain last 2 days | 60.7 (14.9) | 64.5 (23.4) | 54.5 (23.6) | 59.8 (21.3) |

| Average pain last 2 days | 46.3 (16.2) | 52.5 (24.3) | 36.3 (24.0) | 45.0 (22.7) |

| Morning stiffness | 44.3 (31.7) | 43.9 (35.7) | 51.5 (28.4) | 46.7 (31.5) |

| Residual stiffness | 25.9 (19.7) | 15.9 (19.8) | 27.8 (17.0) | 23.0 (19.2) |

| Minutes stiffness | 9.4 (11.0) | 8.0 (10.4) | 10.6 (8.1) | 9.3 (9.7) |

| Morning pain | 50.1 (32.0) | 55.9 (27.1) | 49.5 (30.4) | 52.0 (29.1) |

| Residual pain | 38.7 (27.8) | 33.3 (24.0) | 33.0 (26.5) | 34.7 (25.5) |

Where applicable, values are mean (SD).

There were no withdrawals, and all subjects returned for the follow up two weeks after the sixth treatment. One cell of follow up data was lost, and the end treatment value was used in subsequent analyses.

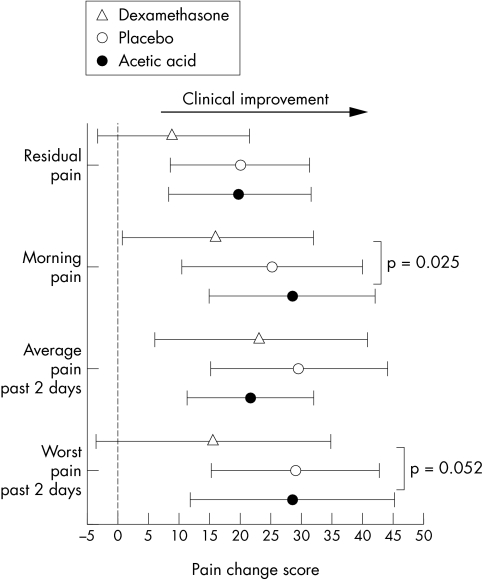

Figure 1 shows the treatment effect for the pain symptoms. All groups showed a significant improvement in morning pain and average pain in the past week. However, for morning pain, the acetic acid/taping showed significantly greater improvement than the dexamethasone/taping intervention. This trend was apparent for residual pain and worst pain in past two days where the dexamethasone/taping intervention was the only group not to reach statistical significance.

Figure 1 Pain change score responses (mean and 95% confidence interval) for the three treatment groups after two weeks of intervention. All scores are related to a 10 cm visual analogue scale, and positive changes reflect clinical benefit.

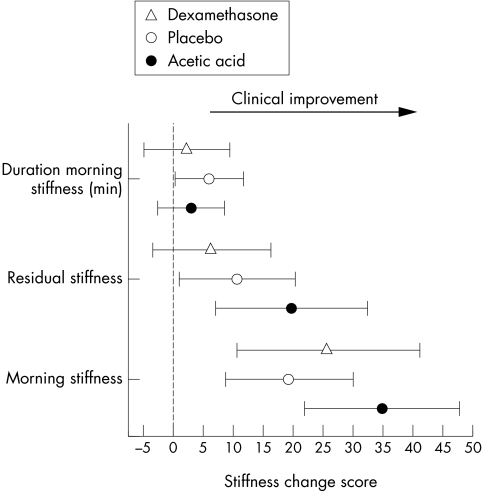

Figure 2 shows the stiffness change scores for the two week interventions. All interventions produced significant improvements in morning stiffness. The placebo/taping and acetic acid/taping groups showed significantly less residual stiffness, whereas this did not reach significance in the dexamethasone/taping group. The placebo/taping group showed significant reduction in the duration of morning stiffness.

Figure 2 Stiffness change score responses (mean and 95% confidence interval) for the three treatment groups after two weeks of intervention. Duration of morning stiffness in minutes and other stiffness scores are related to a 10 cm visual analogue scale, and positive changes reflect clinical benefit.

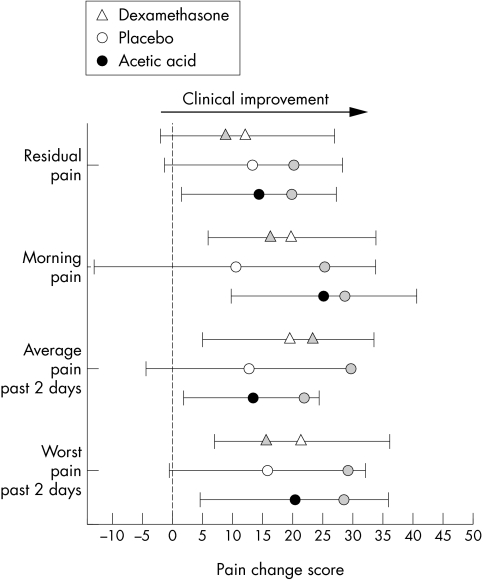

Figures 3 and 4 show the change scores from the baseline to the four week follow up. The additional grey markers show the mean change score at the end of the treatment phase. Note that, for the pain symptoms, acetic acid/taping and placebo/taping showed a loss of treatment effect. This is particularly clear for placebo/taping, where the gains during taping are lost and none of the change scores are significant at the 95% confidence level. In comparison, the decline in pain symptoms response is small for acetic acid/taping and the gains remain significant. The dexamethasone/taping group showed a continued improvement from the initial two weeks of treatment. This may be because this intervention was not very effective in the initial two weeks.

Figure 3 Pain change score responses (mean and 95% confidence interval) from initial assessment to four week follow up for the three treatment groups. All scores are related to a 10 cm visual analogue scale, and positive changes reflect clinical benefit. Grey markers show status at the end of the two week intervention showing level of maintenance/loss of clinical effect. Note that placebo/taping tended to show greatest loss of clinical benefits.

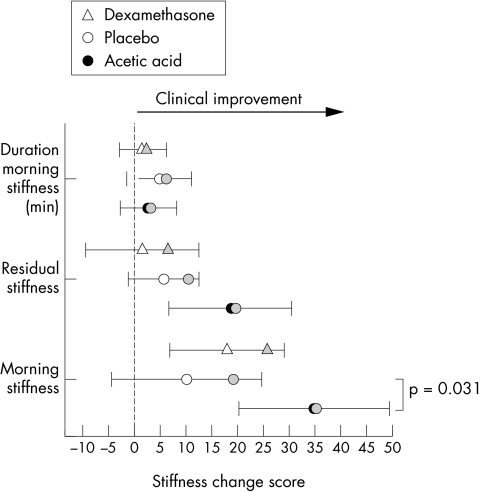

Figure 4 Stiffness change score responses (mean and 95% confidence interval) from initial assessment to four week follow up for the three treatment groups. Grey markers show status at the end of the two week intervention showing level of maintenance/loss of clinical effect. Note that maintenance of clinical benefit is most obvious in acetic acid/taping group.

The stiffness follow up data show a different pattern. Relatively large losses of treatment effect in the placebo/taping and dexamethasone/taping treatments are seen compared with the maintained treatment response of the acetic acid/taping group. In the acetic acid/taping group, significance for morning stiffness and residual stiffness was maintained, and this reflected a significant difference between this group and the placebo/taping group (p = 0.031).

Several patients reported pain that did not ease off in the morning and lasted all day. There were no patients who reported stiffness that did not resolve after a period of time.

Five patients developed skin irritation from taping; one patient found the tape very uncomfortable and in two patients the skin did not tolerate the mechanical loading and peeled. Four of these patients did not complete the full course of taping but all completed the course of iontophoresis. Of these four patients, two were in the placebo group and one in each of the active drug treatment groups. No patients needed treatment for these skin problems other than cessation of taping.

Patients did not guess the group to which they were allocated with more accuracy than chance (χ2 = 0.150, p = 0.699).

Discussion

The results of the study suggest that taping (combined with limited stretching) provides initial short term reduction of both pain and stiffness symptoms in people with PF when used with placebo or acetic acid iontophoresis. In terms of the ability to maintain these changes after an additional two weeks of no intervention, it is clear that this effect was maintained in the acetic acid group, whereas the greatest attenuation of relief—that is, return—of both pain and stiffness symptoms occurred in the placebo group.

The benefits of taping found in this study are consistent with research in which mechanical adaptations—that is, taping, orthoses—are prescribed.8,9 In the clinical setting, LowDye taping results in almost immediate changes in symptoms. It is proposed that, during this short term alleviation of symptoms, the adjunct management options have time to reach therapeutic thresholds.

Continuous taping, however, is difficult as patients become sensitive to the tape. This may lead to skin breakdown. In this study, the two weeks of taping resulted in about 23% of cases in which there were clinically noticeable changes to the skin by the end of the two weeks. This suggests that longer term use of taping may be problematic and any adjunct intervention that prolongs the treatment effect would be of great benefit.

The results for the dexamethasone/taping group showed a different pattern of response. Firstly, this group tended not to show the magnitude of improvement of the other two groups at the end of the initial treatment. Acetic acid produced significantly greater improvements in morning pain than dexamethasone. The change scores of the dexamethasone group failed to reach significance for the worst pain and residual stiffness scores unlike the other two groups.

Secondly, continued resolution of the pain during the no treatment period was only observed in the dexamethasone group. This was observed for all the assessments of pain.

It is unclear why, or if, the LowDye taping affected the effectiveness of the dexamethasone, as it would seem that this combination did not achieve the same early responses as the acetic acid/taping and placebo/taping alone.

Importantly, although the continued improvement in pain symptoms of the dexamethasone group during the no treatment period is clear, the group change scores provide no evidence that it outperformed acetic acid across either domain of pain or stiffness at any assessment point.

One aspect of interest was the different responses to pain and stiffness in the population tested in this study. The greatest clinical response of acetic acid/taping was the alleviation of morning stiffness where the sustained improvements in the dexamethasone group were noted only for pain. These findings may suggest that the symptoms of PF that reduce function are pain and stiffness, and there may be slight differences in the type of symptoms people experience. This may reflect subgroups within the PF population and therefore may have a prognostic value in the choice of intervention. Further research may suggest different combinations of interventions to target the primary symptomatic complaint.

What is already known on this topic

Two studies have looked at iontophoresis of drugs for the treatment of plantar fasciitis; one is a randomised, placebo controlled trial using dexamethasone that shows good outcomes from this treatment

The other is an uncontrolled clinical trial of acetic acid with outcomes that are perhaps better than that of dexamethasone

What this study adds

This study shows that both drugs, when delivered via iontophoresis in combination with LowDye taping, give good short term relief, with acetic acid being at least as good as, if not better than, dexamethasone

The benefits of taping are reduced when it is stopped; however, when it is combined with iontophoresis, treatment effects are maintained

The timeline of the intervention was relatively short and of a mixed (intervention) mode. Rapid change in the primary symptoms that restrict the activities of daily living was the basis for the research design. This reflects the current clinical practice of many treating physicians.

Conclusion

This study found that a protocol of six treatments of acetic acid iontophoresis combined with taping provides greatest relief of the stiffness symptoms of PF. LowDye taping provides a short term window of opportunity in the management of symptoms of PF. Once taping is stopped, this effect wears off, but, if iontophoresis of acetic acid or dexamethasone is used in combination with taping, significant treatment effects persist at four weeks. For the best clinical results at four weeks, acetic acid iontophoresis/LowDye taping is the preferred treatment option over dexamethasone iontophoresis/LowDye taping or taping alone.

Footnotes

Competing interests: none declared

References

- 1.Bennett P J, Patterson C, Dunne M P. Health‐related quality of life following podiatric surgery. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc 200191164–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bennett P J, Patterson C, Wearing S.et al Development and validation of a questionnaire designed to measure foot‐health status. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc 199888419–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kibler W B, Goldberg C, Chandler T J. Functional biomechanical deficits in running athletes with plantar fasciitis. Am J Sports Med 19911966–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Campbell J W, Inman V T. Treatment of plantar fasciitis and calcaneal spurs with the UC‐BL shoe insert. Clin Orthop 1974(103)57–62. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Furey J G. Plantar fasciitis. The painful heel syndrome. J Bone Joint Surg [Am] 197557672–673. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baxter D.The foot and ankle in sport. St Louis: Mosby, 1995

- 7.Kwong P K, Kay D, Voner R T.et al Plantar fasciitis. Mechanics and pathomechanics of treatment. Clin Sports Med 19887119–126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goulet M J. Role of soft orthosis in treating plantar fasciitis. Suggestion from the field. Phys Ther 1984641544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gross M T, Byers J M, Krafft J L.et al The impact of custom semirigid foot orthotics on pain and disability for individuals with plantar fasciitis. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 200232149–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lynch D M, Goforth W P, Martin J E.et al Conservative treatment of plantar fasciitis. A prospective study. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc 199888375–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Probe R A, Baca M, Adams R.et al Night splint treatment for plantar fasciitis. A prospective randomized study. Clin Orthop 1999368190–195. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Powell M, Post W R, Keener J.et al Effective treatment of chronic plantar fasciitis with dorsiflexion night splints: a crossover prospective randomized outcome study. Foot Ankle Int 19981910–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.DiGiovanni B F, Nawoczenski D A, Lintal M E.et al Tissue‐specific plantar fascia‐stretching exercise enhances outcomes in patients with chronic heel pain. A prospective, randomized study. J Bone Joint Surg [Am] 2003851270–1277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chandler T J, Kibler W B. A biomechanical approach to the prevention, treatment and rehabilitation of plantar fasciitis. Sports Med 199315344–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barry L D, Barry A N, Chen Y. A retrospective study of standing gastrocnemius‐soleus stretching versus night splinting in the treatment of plantar fasciitis. J Foot Ankle Surg 200241221–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Scranton P E, Jr, Pedegana L R, Whitesel J P. Gait analysis. Alterations in support phase forces using supportive devices. Am J Sports Med 1982106–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boddeker R, Schafer H, Haake M. Extracorporeal shockwave therapy (ESWT) in the treatment of plantar fasciitis: a biometrical review. Clin Rheumatol 200120324–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Buchbinder R, Ptasznik R, Gordon J.et al Ultrasound‐guided extracorporeal shock wave therapy for plantar fasciitis: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 20022881364–1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Basford J R, Malanga G A, Krause D A.et al A randomized controlled evaluation of low‐intensity laser therapy: plantar fasciitis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 199879249–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cunnane G, Brophy D P, Gibney R G.et al Diagnosis and treatment of heel pain in chronic inflammatory arthritis using ultrasound. Semin Arthritis Rheum 199625383–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kamel M, Kotob H. High frequency ultrasonographic findings in plantar fasciitis and assessment of local steroid injection. J Rheumatol 2000272139–2141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kane D, Greaney T, Bresnihan B.et al Ultrasound guided injection of recalcitrant plantar fasciitis. Ann Rheum Dis 199857383–384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gudeman S D, Eisele S A, Heidt R S., Jret al Treatment of plantar fasciitis by iontophoresis of 0.4% dexamethasone. A randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled study. Am J Sports Med 199725312–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Japour C J, Vohra R, Vohra P K.et al Management of heel pain syndrome with acetic acid iontophoresis. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc 199989251–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hammer D S, Adam F, Kreutz A.et al Extracorporeal shock wave therapy (ESWT) in patients with chronic proximal plantar fasciitis: a 2‐year follow‐up. Foot Ankle Int 200324823–828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hlavac H.The foot book. Mountain View, CA: World Publications, 1977

- 27.Russo S J, Chipchase L S. The effect of low‐Dye taping on peak plantar pressures of normal feet during gait. Aust J Physiother 200147239–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Keenan A M, Tanner C M. The effect of high‐Dye and low‐Dye taping on rearfoot motion. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc 200191255–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vickers A J, Altman D G. Statistics notes: analysing controlled trials with baseline and follow up measurements. BMJ 20013231123–1124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]