Abstract

Background

Creatine supplementation is popular among tennis players but it is not clear whether it actually enhances tennis performance.

Objectives

To examine the effects of creatine supplementation on tennis specific performance indices.

Methods

In a randomised, double blind design, 36 competitive male tennis players (24 creatine, mean (SD) age, 22.5 (4.9) years; 12 placebo, 22.8 (4.8) years) were tested at baseline, after six days of creatine loading, and after a maintenance phase of four weeks (14 creatine, 10 placebo). Serving velocity (10 serves), forehand and backhand velocity (three series of 5×8 strokes), arm and leg strength (bench press and leg press), and intermittent running speed (three series of five 20 metre sprints) were measured.

Results

Compared with placebo, neither six days nor five weeks of creatine supplementation had a significant effect on serving velocity (creatine: +2 km/h; placebo: +2 km/h, p = 0.90); forehand velocity (creatine: +4 km/h; placebo: +4 km/h, p = 0.80), or backhand velocity (creatine: +3 km/h; placebo: +1 km/h, p = 0.38). There was also no significant effect of creatine supplementation on repetitive sprint power after 5, 10, and 20 metres, (creatine 20 m: −0.03 m/s; placebo 20 m: +0.01 m/s, p = 0.18), or in the strength of the upper and lower extremities.

Conclusions

Creatine supplementation is not effective in improving selected factors of tennis specific performance and should not be recommended to tennis players.

Keywords: dietary supplements, racquet sports, creatine supplementation

Creatine is a popular dietary supplement and is believed to enhance performance in various high intensity sports, but not endurance sports.1,2 Creatine supplementation is also popular among tennis players, but it is not clear whether it can actually enhance tennis performance. We were able to identify only one study that had investigated the effect of short term creatine supplementation on stroke performance in tennis.3 In that study, no performance enhancing effect was demonstrated.

Tennis can be characterised as a multiple sprint sport.4 It consists of bouts of intermittent high intensity activity, where the energy demands differ from either pure sprinting or pure endurance running. Single rallies, on average, only last three to eight seconds, generally followed by sufficient recovery time for restoration of phosphocreatine (PCr) stores (up to 25 seconds).5 Complete matches may last longer than three hours, and the overall metabolic response in tennis resembles prolonged moderate intensity exercise.6,7 Mean oxygen consumption during a game of tennis has been shown to be 50–60% of V̇o2max at a heart rate of 140 to 160 beats/minute.8 This raises the question of whether tennis players may benefit from creatine supplementation.

The aim of our study was to determine the effects of both short term (six days) and medium term (five weeks) use of creatine on selected aspects of tennis specific training. We chose to study those situations where an ergogenic effect of creatine is most likely to occur: tennis specific running (repetitive short sprints), velocity of repeated ground strokes, and serving velocity.

Methods

Participants

The study participants were 36 healthy, non‐vegetarian, male tennis players of International Tennis Number 3 (ITN 3) standing or higher. None of the players had used any creatine supplements in the two months preceding the study period. After the players had received detailed information on the study protocol, they gave their written informed consent. The medical ethics committee of the German Sports University approved the study.

Experimental design

The study had a double blind, placebo controlled design. Players were assigned at random to either the creatine group or the placebo group. The supplementation dosage is shown in table 1.

Table 1 Dosage of creatine supplementation.

| Creatine group (dose/kg body weight/d) | Placebo group (dose/kg body weight/d) | |

|---|---|---|

| Loading phase (6 days) | 0.3 g creatine | 0.42 g maltodextrose |

| 0.12 g maltodextrose | 0.12 g dextrose | |

| 0.12 g dextrose | ||

| Maintenance phase (28 days) | 0.03 g creatine | 0.042 g maltodextrose |

| 0.012 g maltodextrose | 0.012 g dextrose | |

| 0.012 g dextrose |

Two creatine products (Podium®, Synergen, Switzerland, and creatine monohydrate, MSD, Netherlands) were used and tested for purity before the start of the study by the department of biochemistry of the German Sports University.

Health variables

Every player was medically examined by a sports physician. Height, weight, and fat percentage, using bioimpedance spectroscopy (Inbody 3.0, Biospace, Seoul, Korea), were determined.9 Venous blood samples were analysed for total blood count, kidney and liver function, and electrolytes. This was repeated after one week and at the completion of the study. Creatine was measured by high performance liquid chromatography.

A maximum exercise test was undertaken using a graded exercise protocol on a cycle ergometer. Maximum oxygen consumption was measured by means of a metabolic cart (Oxycongamma, Mijnhardt, Bunnik, Netherlands). A cardiologist carried out an echocardiogram on each player.

All subjects kept a daily log of their activity pattern, general level of wellbeing, and incidence of muscle soreness and muscle cramps on a scale from 1 to 5. In addition, all subjects filled in a questionnaire at the end of the study, aimed at revealing any changes in dietary intake.

Field tests

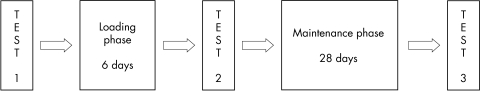

The performance tests were conducted at the start of the study (test 1), after six days of creatine loading (test 2), and after a four week maintenance phase (test 3) (fig 1).

Figure 1 Design of the study.

Service test

After the warm up, a right handed player had to hit 10 first serves (5×2) down the middle from the right side of the court (left handed player to left court). In the service court, an area of 1×2 metres was covered by black plastic, which was the target area for the player. The player was asked to hit each serve as fast as possible, comparable with a first serve in a match situation. Ball velocity was measured with a digital Doppler radar gun (SEA Fiedel GmbH, Rudersberg, Germany). The speed of the serve was displayed and recorded. The mean and highest speed of the 10 serves were analysed.

Ball machine ground stroke drill

The ball machine ground stroke drill was carried out with two players, who had to alternate hitting eight balls in a row. They each performed 60 forehands and 60 backhands, in three series of 40. The balls were alternately fed to the forehand and backhand corner of the baseline by a ball machine (Miha 100 tr, Augsburg, Germany). The ball machine was set up at a velocity of 18 balls/min (feeding velocity 60 km/h). The player had to hit the balls as hard as possible, but still with precision, down the line into a target area. The velocity of the forehand and backhand shots was measured by two radar guns. Maximum speed of each shot was displayed and recorded. The rest periods between each series lasted two minutes. Heart rate (Polar Vantage, Kempele, Finland) was recorded continuously. Blood lactate concentrations from capillary blood from the earlobe (20 μl) (Eppendorf‐Analyser 5060, Hamburg, Germany) and the rate of perceived exertion (RPE) were measured after the warm up and in each series.10 The mean and highest velocities of the 60 forehands and 60 backhands were analysed.

Intermittent sprint test

The sprint test consisted of a total of 15 short sprints, each over 20 metres, following a standardised sprint specific warm up. The sprints were divided into three series of five sprints, with a 30 second rest period between every sprint and a two minute rest period between each series. Running time was measured electronically after 5, 10, and 20 metres with a double combined photocell (Race Time 2, micro Gate Type SMR). Time keeping started automatically as soon as the subject left the starting plate. The mean and best results of the 15 different sprints were determined. RPE and lactate levels were measured at rest and during the breaks after the first, second, and third series.

Strength measurement

Strength was measured by using a computerised leg press and bench press (Desmotronic, Schnell, Germany), with a permanently installed electronic Newton metre.

Leg press

After an individual warm up, the isometric strength of the leg muscles was tested for three seconds. This was repeated three times, with a one minute rest in between. The knee angle was set at 120°. The mean and best values of the three leg press measurements were analysed.

Bench press

After an individual warm up, the maximum isometric strength of the chest and arm muscles was tested for three seconds. This was repeated five times, with a one minute rest in between the individual measurements. The elbow angle was set at 90°. The mean and best values for the five bench press measurements were determined.

Statistical analysis

The creatine group and the placebo group were compared at the start of the study, using an unpaired t test. To investigate the effect of the creatine supplementation, the differences between the baseline tests and subsequent tests were calculated. The differences for the two groups were compared using an ANOVA for repeated measurements, with the baseline score as a covariate. A χ2 test was used to determine whether there were any significant differences in eating habits and activity patterns between the two groups. The level of significance was set at p<0.05.

Results

Test 1: Baseline levels

There were no significant differences in age, height, weight, fat percentage, maximum oxygen uptake, and maximum power between the two groups. Physical examination, ECG, exercise test, echocardiogram, and blood tests revealed no abnormalities. There were no differences between the creatine group and the placebo group in terms of serving velocity, forehand and backhand velocity, sprinting velocity, leg press, and bench press (table 2).

Table 2 Subject characteristics.

| Creatine (n = 24) | Placebo (n = 12) | p Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| Anthropometrics | |||||

| Height (cm) | 182.2 | 5.6 | 181.8 | 6.9 | 0.83 |

| Age (years) | 22.5 | 4.9 | 22.8 | 4.8 | 0.90 |

| Body weight (kg) | 73.9 | 8.5 | 74.6 | 7.9 | 0.82 |

| Fat percentage (%) | 10.3 | 2.5 | 11.6 | 3.2 | 0.18 |

| V̇o2max (ml/kg/min) | 52.3 | 5.8 | 53.2 | 5.4 | 0.65 |

| Maximum power (W) | 351.5 | 42.7 | 372.9 | 56.9 | 0.21 |

| Maximum power (W/kg) | 4.8 | 0.6 | 5.0 | 0.5 | 0.32 |

| Urine chemistry | |||||

| PH | 7.0 | 0.7 | 6.3 | 0.7 | 0.02* |

| Density (kg/l) | 1.02 | 0.01 | 1.02 | 0.01 | 0.18 |

| Creatine (μmol/l)† | Bdl | bdl | |||

| Strength test | |||||

| Bench press (newton, mean) | 597 | 126 | 569 | 199 | 0.62 |

| Bench press (newton, best) | 651 | 158 | 618 | 212 | 0.60 |

| Leg press (newton, mean) | 4373 | 994 | 3797 | 857 | 0.11 |

| Leg press (newton, best) | 4688 | 1083 | 4191 | 953 | 0.20 |

| Sprint test | |||||

| 5 m sprint time (s) | 1.01 | 0.04 | 1.00 | 0.05 | 0.79 |

| 10 m sprint time (s) | 1.79 | 0.06 | 1.78 | 0.08 | 0.76 |

| 20 m sprint time (s) | 3.14 | 0.10 | 3.15 | 0.14 | 0.96 |

| Serum lactate pre (mmol/l) | 2.1 | 0.6 | 2.1 | 0.8 | 0.96 |

| Serum lactate post (mmol/l) | 7.1 | 2.2 | 6.4 | 2.5 | 0.44 |

| RPE post | 17 | 2 | 16 | 2 | 0.065 |

| Tennis test | |||||

| Service (km/h, mean) | 167 | 10 | 170 | 15 | 0.38 |

| Service (km/h, best) | 173 | 10 | 177 | 16 | 0.38 |

| Forehand (km/h, mean) | 124 | 10 | 127 | 98 | 0.33 |

| Forehand (km/h, best) | 137 | 10 | 142 | 10 | 0.21 |

| Backhand (km/h, mean) | 117 | 7 | 120 | 10 | 0.22 |

| Backhand (km/h, best) | 133 | 8 | 138 | 12 | 0.13 |

| Serum lactate pre (mmol/l) | 3.2 | 1.1 | 3.5 | 1.2 | 0.47 |

| Serum lactate post (mmol/l) | 6.3 | 2.6 | 5.7 | 2.4 | 0.54 |

| Heart rate (beats/min) | 180 | 9 | 179 | 9 | 0.60 |

| RPE post | 15 | 3 | 14 | 1 | 0.29 |

*p<0.05.

†Data given for the median score at baseline per supplement group (bdl, median score lies below detection levels (<0.23 mmol/l)).

RPE, rate of perceived exertion.

Test 2: Six day loading phase

There was a large increase in the urinary creatine levels in the creatine group (20.1 mmol/l), suggesting good compliance by the subjects. In the placebo group, creatine concentration was below the detection level.

There was no significant difference in change in body weight between the two groups (mean (SD): creatine, +0.9 (0.9) kg; placebo, +0.5 (0.9), p = 0.24).

There were no differences in performance between the two groups for the leg and bench press measurements, sprinting time, serving velocity, or ground stroke velocity (table 3).

Table 3 Absolute changes in performance indices after six days of creatine loading.

| Creatine (n = 24) | Placebo (n = 12) | p Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| Strength test | |||||

| Bench press (newton, mean) | 35 | 79 | 10 | 40 | 0.31 |

| Bench press (newton, best) | 21 | 73 | −5 | 56 | 0.27 |

| Leg press (newton, mean) | −70 | 641 | 315 | 599 | 0.87 |

| Leg press (newton, best) | −119 | 729 | −101 | 548 | 0.62 |

| Sprint test | |||||

| 5 m sprint time (s) | −0.01 | 0.02 | −0.01 | 0.03 | 0.99 |

| 10 m sprint time (s) | 0.01 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.11 | 0.48 |

| 20 m sprint time (s) | 0.01 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.12 | 0.25 |

| Serum lactate post (mmol/l) | −0.1 | 1.0 | −0.4 | 0.6 | 0.48 |

| RPE post | −1.2 | 1.3 | 0.2 | 1.6 | 0.11 |

| Tennis test | |||||

| Service (km/h, mean) | 2 | 6 | 2 | 6 | 0.90 |

| Service (km/h, best) | 1 | 5 | 1 | 6 | 0.91 |

| Forehand (km/h, mean) | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 0.80 |

| Forehand (km/h, best) | 6 | 5 | 6 | 12 | 0.95 |

| Backhand (km/h, mean) | 3 | 5 | 1 | 4 | 0.38 |

| Backhand (km/h, best) | 3 | 4 | −2 | 7 | 0.065 |

| Serum lactate post (mmol/l) | −1.0 | 1.3 | −0.1 | 1.5 | 0.06 |

| RPE post | −0.5 | 2.2 | 0.0 | 1.1 | 0.45 |

The differences between the two groups were compared using analysis of variance for repeated measurements, with the baseline score as a covariate. The p values for the group comparisons are shown.

RPE, rate of perceived exertion.

Test 3: Four week maintenance phase

The size of the groups was reduced after the loading phase (creatine n = 14, placebo n = 10), because 12 subjects started a specific strength training programme.

The urinary creatine concentrations of the creatine group were increased (7.2 mmo/l), indicating good compliance during the maintenance phase. In the placebo group, creatine concentration was below detection level.

There was a significant increase in total body weight in the creatine group in comparison with the placebo group (creatine, +1.4 (1.1) kg; placebo, −0.2 (2.0), p = 0.02). There were no differences in performance between the two groups for the leg and bench press measurements, sprinting time, serving velocity, or ground stroke velocity (table 4).

Table 4 Absolute changes in performance parameters after six days of creatine loading and a four week maintenance phase.

| Creatine (n = 14) | Placebo (n = 10) | p Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| Strength test | |||||

| Bench press (newton, mean) | 58 | 89 | 86 | 182 | 0.56 |

| Bench press (newton, best) | 65 | 102 | 96 | 217 | 0.54 |

| Leg press (newton, mean) | 242 | 691 | 394 | 801 | 0.94 |

| Leg press (newton, best) | 255 | 794 | 318 | 802 | 0.92 |

| Sprint test | |||||

| 5 m sprint time (s) | −0.01 | 0.03 | −0.01 | 0.04 | 0.90 |

| 10 m sprint time (s) | −0.02 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.24 |

| 20 m sprint time (s) | −0.03 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.18 |

| Serum lactate post (mmol/l) | −0.2 | 0.6 | −0.3 | −0.7 | 0.57 |

| RPE post | −0.8 | 2.1 | −0.7 | 1.6 | 0.57 |

| Tennis test | |||||

| Service (km/h, mean) | 3 | 6 | 0 | 7 | 0.42 |

| Service (km/h, best) | 2 | 7 | 0 | 8 | 0.38 |

| Forehand (km/h, mean) | −1 | 9 | −1 | 3 | 1.00 |

| Forehand (km/h, best) | 2 | 9 | 2 | 9 | 0.90 |

| Backhand (km/h, mean) | 1 | 8 | −3 | 4 | 0.31 |

| Backhand (km/h, best) | 2 | 7 | 2 | 8 | 0.98 |

| Serum lactate post (mmol/l) | −2.5 | 0.92 | −2.7 | 1.2 | 0.36 |

| RPE post | −1.8 | 1.7 | −1.0 | 1.2 | 0.34 |

The differences between the two groups were compared using an analysis of variance for repeated measurements, with the baseline score as a covariate. The p values for the group comparisons are shown.

RPE, rate of perceived exertion.

Health variables

No gastrointestinal complaints or muscle cramps were reported in the course of the study. All blood tests remained normal. The two groups had similar eating habits and activity patterns throughout the study.

Discussion

Our aim in this study was to determine whether creatine supplementation enhances performance in male tennis players. It has been postulated that creatine supplementation may be ergogenic in situations where a high stroke velocity is repeatedly required, and strength training has been shown to lead to improved performance—for example, when hitting first serves or forehand winners.11,12 However, no performance enhancing effect on service velocity or forehand and backhand velocities could be demonstrated.

In the present study, we chose slightly longer rally duration (eight strokes in 25 seconds) than is usual in tennis. Our intention was to simulate peak work loads during match play, because in these situations insufficient recovery time for restoration of PCr stores may occur and an ergogenic effect of creatine supplementation (if it exists) is most likely to be found. As we did not find any ergogenic effect of creatine supplementation on metabolism and stroke velocity in this test situation, it seems reasonable to conclude that it is unlikely that creatine will be beneficial during long rallies.

Our results confirm the study results of Op 't Eijnde et al,3 who did not find any ergogenic effect of creatine on stroke performance or a 70 metre shuttle run. However, this study examined the effects of five days of creatine supplementation, so that only the short term effects of creatine could be determined.13,14 The present study also investigated the possible positive effects of long term (five weeks) supplementation on tennis performance. However, even after this longer supplementation period, no performance enhancing effect was found.

Sprinting velocity and maximum strength

In order to mimic tennis play as much as possible, sprint time was determined after 5, 10, and 20 metres, with three series of five sprints. This resembled tennis play, where players have 25 seconds between points, and 90 seconds between games. However, no significant performance enhancing effect of creatine could be found, and it is therefore unlikely that there would be any effect on sprinting time when chasing a ball on a tennis court.

In this study no effect of creatine supplementation on maximum isometric strength could be demonstrated. Published reports are equivocal regarding the effect of creatine supplementation on isometric force production.15,16,17 We conclude that without extra strength training creatine supplementation is not effective at enhancing isometric strength in young male competitive tennis players.

Health variables

No negative effects of creatine supplementation on liver and kidney function were found, which is in accordance with previous studies.18,19,20 Compared with placebo, a slight (1–1.5 kg) increase in body weight was found after medium term creatine supplementation. This has also been reported in most previous studies.1,2

What is already know on this topic

Creatine has a performance enhancing effect in some high intensity, short duration sporting activities

Short term creatine supplementation does not have an ergogenic effect on stroke production in tennis

What this study adds

Medium term creatine supplementation did not enhance any aspect of tennis specific performance

Creatine supplementation cannot be recommended for tennis players for performance enhancement

Limitations of the study

The study had a number of dropouts after the second testing day. These were players who added strength training to their programme.

Conclusions

Creatine supplementation in tennis players, whether short term or medium term, has not been shown to enhance tennis specific performance. Thus creatine supplementation should not be recommended to tennis players for performance enhancement. Further studies are needed to determine whether creatine supplementation may be beneficial for tennis players in combination with a strength training programme.

Acknowledgements

This study was an NOC*NSF Body of Knowledge project performed with financial support from NOC*NSF, KNLTB, ITF and the German Sports University. The assistance of Wart van Zoest, Markus Walker, Uwe Schmidt and Sven Pieper is gratefully acknowledged. We would like to thank DSM and Synergen AG for the supply of the creatine for the study.

Abbreviations

PCr - phosphocreatine

RPE - rate of perceived exertion

Footnotes

Competing interests: none declared

References

- 1.Volek J S, Rawson E S. Scientific basis and practical aspects of creatine supplementation for athletes. Nutrition 200420609–614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kreider R B. Effects of creatine on performance and training adaptations. Mol Cell Biochem 200324489–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Op 't Eijnde B, Vergauwen L, Hespel P. Creatine loading does not impact on stroke performance in tennis. Int J Sports Med 20012276–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lees A. Science and major racket sports: a review. J Sports Sci 200321707–732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.O'Donoghue P, Ingram B. A notational analysis of elite tennis strategy. J Sports Sci 200119107–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bergeron M F, Maresh C M, Kraemer W J.et al Tennis: a physiological profile during match play. Int J Sports Med 199112474–479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Christmass M A, Richmond S E, Cable N T.et al Exercise intensity and metabolic response in singles tennis. J Sports Sci 199816739–747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ferrauti A, Bergeron M F, Pluim B M.et al Physiological responses in tennis and running with similar oxygen uptake. Eur J Appl Physiol 20018527–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Armstrong L E, Kenefick R W, Casellani J W.et al Bioimpedance spectroscopy technique: intra‐, extracellular, and total body water. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1998291657–1663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Borg G. Perceived exertion: a note on history and methods. Med Sci Sports 1973590–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kramer W J, Ratamess N, Fry A C.et al Influence of resistance training volume and periodization on physiological performance adaptations in collegiate women tennis players. Am J Sports Med 200028626–633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Treiber F A, Lott J, Duncan J.et al Effects of Theraband and lightweight dumbbell training on shoulder rotation torque and serve performance in college tennis players. Am J Sports Med 199826510–515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Greenhaff P L, Bodin K, Söderlund K.et al Effect of oral creatine supplementation on skeletal muscle phosphocreatine resynthesis. Am J Physiol 1994266E725–E730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harris R C, Söderlund K, Hultman E. Elevation of creatine in resting and exercised muscle of normal subjects by creatine supplementation. Clin Sci 199283367–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Earnest C, Snell P, Rodriguez R.et al The effect of creatine monohydrate ingestion on anaerobic power indices, muscular strength and body composition. Acta Physiol Scand 1995153207–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Francaux M, Poortmans J R. Effects of training and creatine supplement on muscle strength and body mass. Eur J Appl Physiol 199980165–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Izquierdo M, Ibanez J, González‐Badillo J J.et al Effects of creatine supplementation on muscle power, endurance, and sprint performance. Med Sci Sports Exerc 200134332–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kreider R B, Melton C, Rasmussen C J.et al Long‐term creatine supplementation does not significantly affect clinical markers of health in athletes. Mol Cell Biochem 200324495–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Poortmans J R, Francaux F. Long‐term oral creatine supplementation does not impair renal function in healthy athletes. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1999311108–1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schilling B K, Stone M H, Utter A.et al Creatine supplementation and health variables: a retrospective study. Med Sci Sports Exerc 200133183–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]