Abstract

The striatum is the main basal ganglia input nucleus, receiving extensive glutamatergic inputs from cortex and thalamus. Medium spiny striatal projection neurons (MSNs) are GABAergic, and their axon collaterals synapse on other MSNs. Approximately 50% of MSNs corelease substance P (SP), but how this neurotransmitter controls MSN activity is poorly understood. We used whole-cell recordings to investigate how SP affects MSNs and their glutamatergic inputs. SP elicited slow depolarizations in 47/90 MSNs, which persisted in the presence of tetrodotoxin (TTX). SP responses were mimicked by the NK1 receptor agonist [Sar9,Met(O2)11]-substance P (SSP), and fully blocked by the NK1 receptor antagonists L-732,138, or extracellular zinc. When intracellular chloride was altered, the polarity of SP responses depended on the sign of the chloride driving force. In voltage-clamp, SP-induced currents reversed around −68 mV and displayed marked inward rectification. These data indicate that SP increased a ClC-2-type chloride conductance in MSNs, acting through NK1 receptors. SP also strongly increased glutamatergic responses in 49/89 MSNs. Facilitation of glutamatergic responses (which was observed both in MSNs directly affected by SP and in non-affected ones) was reduced by application of L-732,138, and fully blocked by coapplication of L-732,138 and SB222200 (an NK3 receptor antagonists), showing that both NK1 and NK3 receptors were involved. SP-induced facilitation of glutamatergic responses was accompanied by a marked decrease in paired-pulse ratio, indicating a presynaptic mechanism of action. These data provide an electrophysiological correlate for the anatomically known connections between SP-positive MSN terminals and the dendrites and somata of other MSNs.

The striatum is the main recipient of cortical and thalamic afferents in the basal ganglia, and plays an essential role in motor control (Graybiel, 2005). Understanding how striatal circuits process these excitatory inputs to generate their motor-related output is one of the central goals in basal ganglia research (Kincaid et al. 1998; Gurney et al. 2004). A prominent anatomical feature of the striatum is the dense local network formed by the axon collaterals of its projection neurons (Wilson & Groves, 1980; Somogyi et al. 1981), which constitute up to 95% of the striatal neuronal population (Graveland & DiFiglia, 1985). These cells are medium-sized spiny neurons (MSNs) and corelease GABA and neuropeptides (Bolam et al. 2000; Tepper et al. 2004). MSN axon collaterals form synapses with several cellular targets, including other MSNs (Wilson & Groves, 1980; Bolam & Izzo, 1988). GABAergic synapses between MSNs are functional, and have been widely studied (Tunstall et al. 2002; Koos et al. 2004; Tepper et al. 2004). One of the neuropeptides coreleased with GABA is substance P (SP), which is expressed by approximately half of the MSN population. This MSN subgroup forms the so called direct pathway, which projects preferentially to output nuclei of the basal ganglia, and also expresses D1 dopamine receptors. The remaining MSNs, which give rise to the indirect pathway, mainly project to the globus pallidus, and express D2 dopamine receptors (Gerfen, 1992; Wang et al. 2006). SP-containing terminals form synapses with spines, dendrites and cell bodies of MSNs of both subpopulations (Bolam et al. 1983; Bolam & Izzo, 1988; Yung et al. 1996). SP binds preferentially to NK1 receptors, although NK2 and NK3 receptors also display substantial affinity for this ligand (Almeida et al. 2004). Immunohistological studies have suggested that postsynaptic NK1 receptors are expressed in the striatum by cholinergic and NOS-positive interneurons, but not by MSNs (Kaneko et al. 1993; Jakab & Goldman-Rakic, 1996). However, these studies used antibodies that did not detect short isoforms of NK1 receptors, which are abundant in the striatum (Baker et al. 2003; Caberlotto et al. 2003). The ability of SP to affect MSNs directly should therefore not be discarded based on cytochemical grounds. Furthermore, presynaptic NK1 receptors are found on glutamatergic terminals in the striatum (Jakab & Goldman-Rakic, 1996), raising the possibility that SP may modulate release of glutamate. Collectively, these observations suggest that SP is a potential modulator of MSNs' excitability and of their glutamatergic inputs, but this action has not been demonstrated with electrophysiological techniques. In order to address this issue, we carried out an investigation of the pre- and postsynaptic effects of SP on MSNs.

Methods

Slice preparation

Wistar rats (14–24 days postnatal, both sexes) were killed by cervical dislocation in accordance with the UK Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986; coronal brain slices (250–300 μm thick) were cut using a vibroslicer (Camden Instruments, Loughborough, UK) and maintained at 25°C in oxygenated artificial cerebro-spinal fluid (ACSF) (mm: 126 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 1.3 MgCl2, 1.2 NaH2PO4, 2.4 CaCl2, 10 glucose and 18 NaHCO3), as previously described (Bracci et al. 2003; Blomeley & Bracci, 2005). For recordings, slices were submerged, superfused (2–3 ml min−1) at 25°C, and visualized with a 40× water-immersion objective (Olympus Optical, Tokyo, Japan) using standard infrared and differential interference contrast microscopy.

Whole-cell recordings

Whole-cell recordings from MSNs were performed with 1.5 mm external diameter borosilicate pipettes, filled with intracellular solution (mm: 125 potassium gluconate, 15 KCl, 0.04 EGTA, 12 Hepes, 2 MgCl2, 4 Na2ATP and 0.4 Na2GTP, adjusted to pH 7.3 with KOH). Two caesium-based intracellular solutions were also used: a low chloride one containing (mm): 140 caesium methanesulfonate, 10 EGTA, 10 Hepes, 2 MgCl2, 4 ATP; 0.4 GTP (pH 7.35), and a high chloride one containing (mm): 140 CsCl, 0.02 EGTA, 10 Hepes, 2 MgCl2, 4 ATP, 0.4 GTP (pH 7.35). With these solutions, pipette resistance was 3–4 MΩ. Recordings in current-clamp mode were performed with bridge amplifiers (Axoclamp 2B, Axon Instruments, Union City, CA, USA; or BA-1S, npi electronic, Tamm, Germany). Recordings in voltage-clamp mode were made using the Axoclamp 2B in continuous single-electrode mode with uncompensated series resistance. Data were acquired at 10–15 kHz using Signal software and a micro1401 data acquisition unit (CED, Cambridge, UK). Input resistance in current-clamp experiments was measured with small current injections (500 ms to 1 s; 15–20 pA) at resting membrane potential. In the presence of a treatment that caused depolarizations, resistance was measured while the cells were briefly repolarized to control level.

Drugs

Drugs were either bath applied through the superfusion system, or locally ejected through a glass patch micropipette (similar to those used for recording) placed 100–250 μm from the recorded cells. In this case, the drug was dissolved in oxygenated ACSF, and pressure was controlled manually through a syringe and a three-way valve. Before each ejection, the pressure inside the syringe was set by moving the plunger between two set levels with the valve closed. The valve connecting the syringe to the glass micropipette was then open for 2 s to allow ejection, and then closed. At this point the syringe was removed and reset to the initial position.

NBQX, AP-5, SP and SSP were obtained from Sigma (Poole, UK) and TTX citrate, atropine sulfate, naloxone hydrochloride, S-(–)-sulpiride, SCH 23390 hydrochloride, CGP 52432, bicuculline, spantide I, L-732,138, SB222200 and (+)-tubocurarine chloride from Tocris Bioscience (Bristol, UK).

Evoked synaptic responses

Glutamatergic responses were recorded in current-clamp mode as excitatory postsynaptic responses (EPSPs) or in voltage-clamp as excitatory postsynaptic currents (EPSCs). These responses were evoked in the striatum with a monopolar electrode consisting of a patch micropipette filled with ACSF. Stimulation amplitude was 10–100 V, and its duration was 0.01–0.1 ms. All the experiments involving evoked glutamatergic responses were carried out in the continuous presence of antagonists of the following receptors: GABAA (bicuculline, 10 μm); GABAB (CGP 52432, 2 μm); opioid (naloxone hydrochloride, 10 μm); dopamine D1 (SCH 23390 hydrochloride, 10 μm); dopamine D2 (S-(–)-sulpiride, 3 μm) and muscarinic (atropine sulfate, 25 μm). Under these conditions, evoked responses, recorded under either current-clamp or voltage-clamp conditions, were completely abolished by coapplication of the ionotropic glutamate receptor antagonists 2,3-dihydroxy-6-nitro-7-sulfonyl benzo[f]quinoxaline (NBQX) 10 μm and AP-5 (10 μm) (n = 20). Either single or paired (50 ms interval) electrical stimuli were applied every 10 or 15 s. These intervals were chosen because, after the first 10 stimuli, the EPSC amplitude did not display a statistically significant trend of variation as a function of time (ANOVA regression analysis always yielded significance levels > 0.05). On the other hand, the first 10 responses were often significantly larger than the following ones, and therefore were always discarded from analysis.

Statistical analysis

Values are expressed as means ±s.d., and statistical comparisons were made using Student's t test for unpaired data. Two populations of data points were considered to be significantly different if P < 0.05.

Results

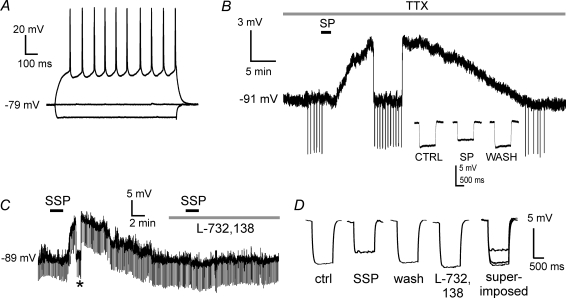

Current- and voltage-clamp whole-cell recordings were obtained from 203 MSNs, identified by their distinctive electrophysiological properties (Kita et al. 1984; Nisenbaum & Wilson, 1995; Bracci et al. 2004). These properties included: resting membrane potentials more negative than −75 mV; strong inward rectification giving rise to asymmetric responses to negative and positive current injections of the same magnitude; slow depolarizing ramps during subthreshold depolarizations; and delayed appearance of action potentials during suprathreshold depolarizing steps. The average resting membrane potential was −79 ± 6 mV. The average input resistance was 214 ± 75 MΩ. Typical MSN responses are illustrated in Fig. 1A.

Figure 1. Effects of SP and SSP on MSNs.

A, typical electrophysiological properties of an MSN. Current injections (± 150 pA) produced strongly asymmetric responses (due to inward rectification) and a slow depolarizing ramp that developed during the positive step, delaying the appearance of action potentials. No current was injected before and after the steps. B, in the presence of TTX (1 μm), a brief application of SP (1 μm; 2 min) elicited a slow depolarization in an MSN recorded in current-clamp conditions. The depolarization peaked 16 min after the start of SP application, and membrane potential returned at control level 39 min after the end of SP application. Each vertical deflection is a series of 5 current pulses, delivered every 10 s to monitor input resistance. During SP-induced depolarization, the cell was transiently repolarized to control level to compare responses to current pulses. The insets show that input resistance was reversibly reduced in the presence of SP (each waveform is the average of 5 consecutive responses). C, bath application of the NK1 receptor agonist SSP (100 nm) induced a slow depolarization in a different MSN. This effect was fully reversed upon washout. Subsequent bath application of L-732,138 (5 μm) prevented any further depolarization by SSP re-application. Vertical deflections are due to current injections (20 pA, 1 s). The asterisk indicates a manual repolarization to control level, applied to compare input resistance. D, in the experiment of Fig. 1C, MSN input resistance (measured when the cell was manually repolarized to control level) was significantly (P < 0.01) reduced with respect to control during the SSP-induced depolarization. This effect was reversed on washout. In the presence of L-732,138 there was a small but significant (P < 0.05) increase in input resistance, and SSP did not affect membrane potential or input resistance. Traces are averages of 10 consecutive pulses for each condition.

Direct effects of SP on MSNs

In order to isolate the recorded MSN from the synaptic influence of the other neurons present in the slice, we carried out a series of experiments in the presence of the sodium channel blocker tetrodotoxin (TTX, 1 μm), which blocks action potential-mediated synaptic transmission; under these conditions, bath application of SP (1 μm, 2 min) reversibly depolarized 4/7 MSNs. These effects (9 ± 2 mV) peaked 17 ± 10 min after the start of the application and were accompanied by a significant (P < 0.05) decrease in input resistance (on average 25 ± 7%). A representative example of these effects is shown in Fig. 1B.

In the presence of TTX, SP effects may be caused by an action potential-independent facilitation of glutamate release (see second part of Results). To test this possibility, we carried out experiments in the presence of TTX and of the ionotropic glutamate receptor blockers AP5 (20 μm) and NBQX (10 μm). Under these conditions, bath-application of glutamate (100 μm) failed to depolarize MSNs or affect their input resistance (n = 5), consistent with the previous observation that activation of metabotropic glutamate receptors does not affect MSN membrane properties (Gubellini et al. 2004).

Nevertheless, in the presence of TTX and glutamate receptor blockers, application of SP (1 μm) elicited depolarizing effects (9 ± 1 mV; time to peak 12 ± 4 min) and a significant (P < 0.01) decrease in input resistance (32 ± 5%) in 4/5 MSNs tested. These effects were not significantly different from those observed in the presence of TTX alone.

In order to study whether the slow time course of SP effects was due to slow penetration of SP in the tissue during bath application, we also tested brief (2 s) local applications of SP. These local applications also elicited depolarizing effects (8 ± 2 mV) in 12/20 MSNs. The time course of these depolarizations was not significantly faster than that observed with bath applications (time to peak 13 ± 7 min); we concluded that SP triggered intrinsically slow cellular responses in MSNs.

Overall, the experiments in the presence of TTX showed that SP depolarized MSNs by acting on postsynaptic receptors. In the CNS, SP exhibits preferential binding for NK1 tachykinin receptors, although NK2 and NK3 receptors also have substantial affinity for SP (Beaujouan et al. 2004). To test the involvement of these receptors, we used the selective NK1 agonist SSP (100 n). In the presence of TTX, bath or local application of SSP elicited depolarizing effects similar to those of SP in 6/9 MSNs (Fig. 1C and D). The remaining three cells were not affected by SSP. SSP-induced depolarizations (9 ± 2 mV) were also accompanied by a significant (P < 0.05) decrease in input resistance (28 ± 3%), as shown in Fig. 1C and D. The time from the start of the application to the peak of the depolarizing effects of SSP (13 ± 7 min) was not significantly different from that of SP.

To further test the involvement of NK1 receptors, we used the selective antagonist L-732,138 (5 μm). Preliminarily, we observed that in the absence of this antagonist, in MSNs in which a first application of SP (n = 5) or SSP (n = 4) had elicited depolarizing effects, a second application of the same agent (after complete washout of the effects) elicited a very similar depolarization (not shown). We then repeated this type of experiment in another group of SP- or SSP-responsive cells, with the difference that L-732,138 was applied before the second application of SP (n = 5) or SSP (n = 3). Under these conditions, the second application of SP or SSP failed to elicit any depolarizing effect. Furthermore, in 5/8 cases, L-732,138 per se caused a small hyperpolarization (1.0 ± 0.5 mV) and a small but significant (P < 0.05) increase in input resistance (11 ± 8%). A representative example of these experiments is illustrated in Fig. 1C and D. We concluded that the depolarizing effects of SP on MSNs were entirely mediated by postsynaptic NK1 receptors.

In order to cast light on the ionic mechanisms responsible for SP effects, we studied the effects of consecutive applications of SSP on MSNs polarized at different levels by steady current injection. A representative example of this type of experiment is shown in Fig. 2A. When kept at −90 mV, the recorded MSN responded to SSP with a slow depolarization. After complete washout of these effects, the MSN was manually depolarized at around −56 mV with a steady current injection. Under these conditions, a new SSP application (identical to the previous one) caused a hyperpolarizing response.

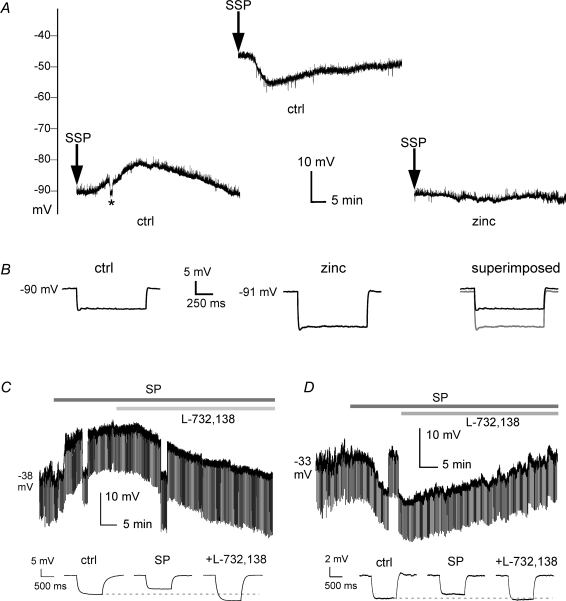

Figure 2. Influence of membrane potential and intracellular chloride on SP- and SSP-induced responses.

A, in this current-clamp experiment, SSP was locally applied (2 s) to an MSN kept at −90 mV. Under these conditions, SSP elicited a slow depolarization that peaked ∼20 min after the application. A complete washout of these effects was observed approximately 50 min after the application. Vertical deflections are due to current injections (20 pA, 1 s), which were used to test input resistance. The asterisk indicates a manual repolarization to control level, to compare input resistance at the same membrane potential. After washout, the MSN was manually depolarized at approximately −45 mV, and local SSP application was repeated. Under these conditions, SSP caused a hyperpolarizing response in the MSN. After recovery, the cell was repolarized at −90 mV and zinc (300 μm) was bath applied. Zinc per se caused a small hyperpolarization (1 mV) and fully prevented the effects of a third application of SSP (right trace). B, in the experiment of panel A, input resistance (measured in both cases with current injections at −90 mV) was significantly (P < 0.05) decreased after SSP application. On the other hand, after zinc application, input resistance was significantly (P < 0.01) increased with respect to control. C, an MSN recorded with CsCl-based intracellular solution was kept at a membrane potential of −38 mV (no steady current injected). SP application (in the presence of TTX) elicited a large depolarization, accompanied by a decrease in input resistance. Subsequent application of L-732,138 caused the cell to repolarize to control levels, and significantly (P < 0.05) increased its input resistance with respect to control value. Input resistance test pulses are shown below the slow time scale trace. D, another MSN, recorded with caesium methanesulfonate-based intracellular solution had a membrane potential of −33 mV (no steady current injected). SP application (in the presence of TTX) elicited a hyperpolarizing response, accompanied by a decrease in input resistance. Subsequent application of L-732,138 caused the membrane potential to revert to control levels, while slightly increasing the cell's input resistance with respect to control value. Input resistance test pulses are shown below the slow time scale trace.

Similar results were observed in 8/10 MSNs tested. When these cells were manually depolarized to levels between −57 and −48 mV, application of SSP (n = 4) or SP (n = 4) triggered hyperpolarizing responses (6.2 ± 2.5 mV) in eight cases, while no response was observed in the remaining two cases.

This suggested that SSP action could be mediated by a chloride current, since the reversal potential for GABA receptors (which are mainly permeable to chloride) in MSNs is in the range of −70 to −60 mV (Koos et al. 2004; Taverna et al. 2004; Bracci & Panzeri, 2006). Consistent with this hypothesis, we found that the effects of SP were completely prevented by bath application of zinc (300 μm), which blocks ClC-2 type chloride conductances (Kajita et al. 2000), in five MSNs previously responsive to SP. Zinc per se caused a slight hyperpolarization (1 ± 0.5 mV) and a significant (P < 0.01) increase in input resistance (41 ± 12%) in these cells. An example of this phenomenon is shown in Fig. 2A and B.

To further test the hypothesis that SP increased a chloride current in MSNs, we used two caesium-based intracellular solutions containing different concentrations of chloride (see Methods). These experiments were carried out in the continuous presence of TTX. When recorded with either of these caesium-based solutions, all MSNs (recorded without steady current injections) displayed spontaneous depolarizations to levels between −40 and −30 mV, consistent with the action of caesium on MSN potassium currents (Nisenbaum & Wilson, 1995). With CsCl-based intracellular solution (for which nominal ECl= 1.4 mV), SP elicited depolarizing responses (13 ± 2 mV) in 5/5 MSNs. These responses were accompanied by a significant (P < 0.01) decrease in input resistance (43 ± 7%). Subsequent addition of L-732,138 (still in the presence of SP) caused a repolarization of MSNs to levels similar to those observed before SP application, and a significant (P < 0.05) increase in input resistance (31 ± 18%) with respect to control. A representative example of these experiments is shown in Fig. 2C. On the other hand, with caesium methanesulfonate-based intracellular solution (nominal ECl=−90.7 mV), SP elicited hyperpolarizing responses (10 ± 2 mV) in 5/7 MSNs, and no effects in the two remaining MSNs. As in the previous case, SP responses were accompanied by a significant (P < 0.01) decrease in input resistance (71 ± 4%), and were completely reversed by subsequent addition of L-732,138, which significantly (P < 0.05) increased input resistance (12 ± 4%) with respect to control. A representative example of these experiments is shown in Fig. 2D. The observation that the polarity of SP responses depended on the sign of the driving force for chloride clearly confirmed that SP's action on MSNs was due to an increased chloride conductance.

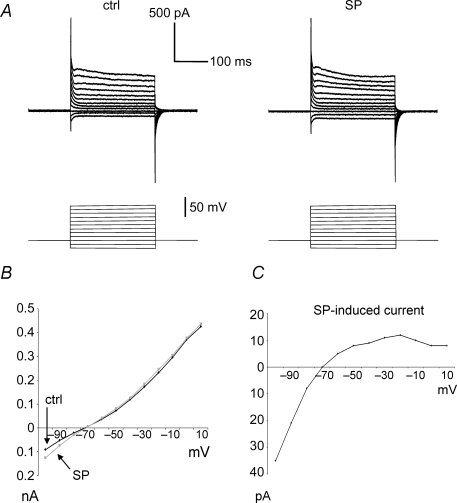

To gain further insight into the biophysical features of the SP-induced currents, we carried out voltage clamp experiments. In the presence of TTX, at holding potential Vh=−80 mV, SP induced inward currents (−38.5 ± 19 pA) in 7/9 MSNs, and no effects in the remaining two MSNs. In the continuous presence of SP, these inward currents fully developed within 15–20 min from the start of the application; these effects showed little signs of desensitization, as the inward currents remained > 90% of their peak value as long as SP was present (we tested periods up to 90 min). Current–voltage relationships were investigated with voltage steps (0.5 s duration) applied from −80 mV to levels between −100 and +10 mV, in 10 mV increments (Fig. 3A). These steps were first applied in control solution, and then in the presence of SP (after > 30 min continuous application) in five MSNs in which SP had elicited an inward current. Typical current traces recorded from an MSN in control solution and in the presence of SP are shown in Fig. 3A. The steady-state currents (measured at the end of each step) are plotted against membrane potential in Fig. 3B. The difference between steady-state currents in SP and in control solution is plotted as a function of voltage in Fig. 3C. This difference current, which represents the current activated by SP, reversed polarity at approximately −70 mV and displayed marked inward rectification. Similar results were observed for the other MSNs. On average, the reversal potential of SP-induced current was −68.3 ± 5.8 mV. We concluded that the chloride current responsible for SP effects had biophysical and pharmacological properties similar to the ClC-2 type current (Clark et al. 1998; Kajita et al. 2000).

Figure 3. Voltage-clamp analysis of SP-induced responses.

A, membrane currents recorded in the presence of TTX from an MSN recorded under voltage-clamp conditions in control solution (left) and after application of SP (1 μm; right). Voltage steps (0.5 s) were applied from the holding value (−80 mV) to levels between −100 and +10 mV (in 10 mV increments). B, steady-state currents (recorded at the end of each voltage step) plotted versus voltage for the experiments of panel D in control solution and in the presence of SP. C, I–V plot for SP-induced currents. The steady-state current induced by SP was calculated for each voltage level by subtracting the value measured in the presence of SP from that measured in control solution. SP-induced current reversed polarity around −70 mV, and displayed marked inward rectification.

Effects of SP on MSN glutamatergic responses

The presence of presynaptic NK1 receptors on glutamatergic terminals in the striatum (Jakab & Goldman-Rakic, 1996), suggests that SP may modulate the release of this transmitter. Therefore, we investigated the effects of SP on evoked glutamatergic responses of MSNs using current-clamp and voltage-clamp recordings. In order to isolate glutamatergic responses and prevent activation of other presynaptic receptors known to affect glutamatergic responses, these experiments were carried out in the presence of GABAA, GABAB, opioid, dopamine and muscarinic receptor antagonists, as described in Methods. Consistent with the results described above, under these conditions, prolonged bath application of SP (1 μm) had direct depolarizing effects on 31/63 MSNs recorded under current-clamp conditions, and elicited inward currents in 14/26 MSNs recorded under voltage-clamp conditions. These inward currents remained stable (i.e. they varied < 10% from peak value), in the presence of SP, over recordings lasting up to 90 min, showing again that there was little desensitization of SP effects. In the remaining 32/63 (current-clamp) and 12/26 MSNs (voltage-clamp), no direct effects of SP were observed. The effects of SP on glutamatergic responses were analysed separately for MSNs that were or were not directly affected by SP. For all experiments, the effects of SP on evoked glutamatergic responses were measured using only responses collected after > 30 min continuous application of SP.

MSNs not directly affected by SP

Under current-clamp conditions, SP induced a significant (P < 0.05) increase in EPSP amplitude (on average by 36 ± 17%) in 13/32 MSNs in which no direct effects of SP were observed. A representative example of this effect is shown in Fig. 4A. In the remaining 19 cells, the EPSP amplitude in the presence of SP was not significantly different from control.

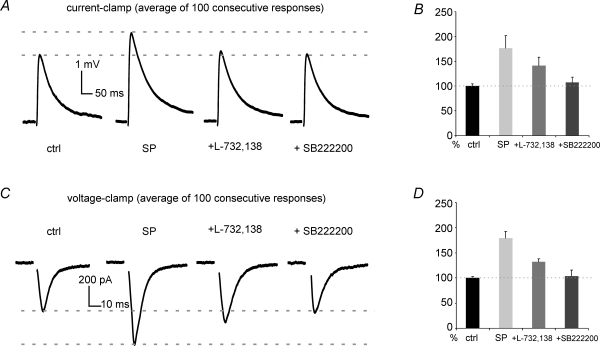

Figure 4. Effects of SP on evoked glutamatergic responses.

The experiments presented in this figure were carried out in the continuous presence of GABAA, GABAB, opioid, dopamine and muscarinic receptor antagonists (see Methods for details). A, in this typical current-clamp experiment, SP did not cause any direct effect on an MSN, but strongly increased the amplitude of its evoked EPSPs. SP effects on EPSP were partially reversed by subsequent application of the NK1 receptor antagonists L-732,138 (in the presence of SP). Subsequent application of the NK3 receptor antagonist SB222200 (1 μm), still in the presence of SP and L-732,138, restored the EPSP amplitude to control levels. Each trace is the average of 100 consecutive responses elicited at 15 s intervals. B, average effect of SP, SP + L-732,138, and SP + L-732,138 + SB222200 on EPSP amplitude as a percentage of control. Data are from 6 current-clamp experiments in which all these treatments were sequentially applied. C, in this experiment, an MSN (different cell from A) was held at −80 mV under voltage-clamp conditions. Bath applied SP (1 μm) did not affect the resting membrane current, but strongly increased the average amplitude of the evoked EPSC. This effect was partially reversed by subsequent application of the NK1 receptor antagonist L-732,138 (in the presence of SP). Subsequent application of the NK3 receptor antagonist SB222200 (still in the presence of SP and L-732,138) restored the EPSC amplitude to control levels. Each trace is the average of 100 consecutive responses elicited at 15 s intervals. Artifacts of electrical stimulation were removed in this and subsequent figures. D, average effect of SP, SP + L-732,138, and SP + L-732,138 + SB222200 on EPSC amplitude as a percentage of control. Data are from 4 voltage-clamp experiments in which all these treatments were sequentially applied.

Under voltage-clamp conditions, SP significantly (P < 0.05) increased EPSC amplitude (on average by 32 ± 20%) in 3/12 MSNs that were not directly affected by SP. An example of this effect is shown in Fig. 4C. In the remaining nine cells, EPSCs were not significantly affected by SP.

Overall, significant potentiation of glutamatergic responses by SP was observed in 16/44 (36%) MSNs not directly affected by SP.

MSNs directly affected by SP

Consistent with the results described in the previous sections, direct SP effects observed in this series of experiments, either in current clamp (as depolarizations) or in voltage-clamp conditions (as inward currents at Vh=−80 mV), were accompanied in all MSNs by a significant (P < 0.05) decrease in input resistance.

In order to study the effects of SP on evoked EPSPs, in current-clamp experiments it was necessary to repolarize manually the MSNs directly affected by SP to control resting level (typically between −80 and −90 mV). In 21/31 of these MSNs, SP induced a significant (P < 0.05) increase in EPSP amplitude (on average by 47 ± 21%). In the remaining 10 cases, the EPSP amplitude in the presence of SP was not significantly different from control. It should be noted that the increase in EPSP amplitude cannot be a consequence of the direct effects of SP on these MSNs, as these effects would be expected to reduce EPSP amplitude due to the shunting effects cause by decreased input resistance.

In voltage clamp experiments, in 12/14 MSNs directly affected by SP, this drug also caused a significant (P < 0.05) increase in evoked EPSC amplitude (on average by 81 ± 57%; Vh=−80 mV). In the other two cells, EPSC amplitude was not significantly affected by SP.

Overall, significant potentiation of glutamatergic responses by SP was observed in 33/45 MSNs (73%) that were directly modulated by SP.

Although nicotinic effects on glutamatergic response have not been reported in the striatum, the possibility exists that these receptors may be activated by acetylcholine released by striatal interneurons in the presence of SP, as nicotinic receptors can modulate glutamatergic responses (Quitadamo et al. 2005). Therefore, we carried out a series of voltage-clamp experiments in the presence of the nicotinic receptor antagonist tubocurarine (in addition to the other antagonists). Under these conditions, SP significantly (P < 0.01) increased EPSC amplitude (by 42 ± 11%) in 6/8 MSNs (4 of which had been directly affected by SP); this result shows that effects of SP on glutamatergic responses were not caused by activation of nicotinic receptors.

In summary, SP significantly increased the amplitude of evoked glutamatergic responses both in MSNs that were directly modulated by it, and in MSNs that were not directly affected. However, SP effects on glutamatergic responses were more frequently observed in MSNs that were also directly modulated by SP.

Pharmacology of SP effects on glutamatergic responses

To identify the receptors involved in the facilitating action of SP on glutamatergic responses, we applied tachykinin receptor antagonists (still in the presence of SP) in 10 experiments in which SP had significantly increased MSN glutamatergic response amplitude in current-clamp (n = 6) or voltage-clamp (n = 4). The 10 MSNs used for these pharmacological experiments included seven cells in which SP had also elicited direct effects, and three in which such direct effects were not observed. The effects of the antagonists tested were similar in the two groups, and therefore were pooled in the analysis. As described in the previous section, those MSNs in which SP had induced a depolarization under current-clamp conditions were manually repolarized to control resting potential to study glutamatergic responses. In each experiment, a single stimulus was continuously applied every 10 or 15 s. Average effects of different pharmacological combinations on the evoked responses of these neurons are shown in the plots of Fig. 4B (current-clamp) and Fig. 4D (voltage-clamp). Individual representative examples are shown in Fig. 4A and C. In these 10 neurons, SP significantly (P < 0.01 for each MSNs) increased EPSP amplitude (on average to 179 ± 13% of control), and EPSC amplitude (to 177 ± 25% of control). Subsequent application of L-732,138 reduced EPSP amplitude, on average, to 132 ± 6% of control, and EPSC amplitude to 142 ± 17% of control. This decrease was statistically significant (P < 0.01) for each MSN. These results suggested that the potentiating effects of SP on glutamatergic responses were partly, but not exclusively, mediated by NK1 receptors. NK3 receptors are also found in the striatum (Stoessl, 1994; Preston et al. 2000; Langlois et al. 2001) and may also mediate the effects of SP. Further application of the NK3 receptor antagonist SB222200 (1 μm), in the presence of SP and L-732,138, caused EPSP (n = 6) and EPSC (n = 4) amplitudes to decrease significantly (P < 0.01 for each MSN) with respect to those recorded in SP and L-732,138 (EPSPs were reduced to 104 ± 12% of control and EPSCs to 102 ± 14% of control). In fact, in the presence of SP, L-732,138 and SB222200, glutamatergic response amplitude was not significantly different from those observed in control solution.

We concluded that the facilitatory effects of SP on glutamatergic responses were mediated by both NK1 and NK3 receptors.

Effects of SP on paired-pulse glutamatergic responses

In order to investigate whether the effects of SP on glutamatergic responses were due to presynaptic or postsynaptic mechanisms, we studied how responses evoked by paired-pulse stimulation were affected by SP. A paired-pulse interval of 50 ms was chosen, as in previous studies where it caused paired-pulse facilitation in MSNs (Calabresi et al. 1997). Modifications of the paired-pulse ratio (i.e. the ratio of second to first response amplitude) are indicative of a presynaptic change in release probability (Manabe et al. 1993; Schulz et al. 1994).

The results were collected from current clamp (n = 5) or voltage-clamp (n = 5) experiments. In each of these MSNs, SP caused a significant (P < 0.05) increase of the first glutamatergic response. In 4 of these 10 MSNs, SP also elicited direct effects, while in the remaining six no direct modulation was observed; results for the paired-pulse experiments were similar in the two groups, and were therefore pooled in the analysis. In each experiment, a paired-pulse stimulation was applied every 10 or 15 s without interruptions. For each MSN, the paired-pulse ratio was measured for each presentation of the paired-pulse stimulus (at least 100 presentations per pharmacological conditions were applied in each case).

In all MSNs tested, SP significantly (P < 0.05) decreased the paired-pulse ratio. Two representative examples of these experiments are shown in Fig. 5A (current-clamp) and C (voltage-clamp). In both cases, paired-pulse facilitation was observed in control solution. In the presence of SP, the amplitude of glutamatergic responses increased, and paired-pulse facilitation was replaced by paired-pulse depression. Average values for the ratio of the second response to the first response amplitude in control solution and in the presence of SP are shown in Fig. 5B and D for current-clamp and voltage-clamp experiments, respectively. We concluded that the facilitatory effects of SP on glutamatergic responses were mediated by a presynaptic mechanism.

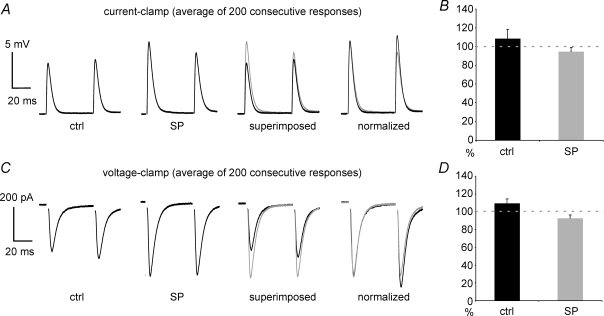

Figure 5. SP converted paired-pulse facilitation of evoked glutamatergic responses into paired-pulse inhibition.

The experiments presented in this figure were carried out in the continuous presence of GABAA, GABAB, opioid, dopamine and muscarinic receptor antagonists (see Methods for details). A, in this representative current-clamp experiment, paired-pulse stimulation (50 ms interval) was applied every 15 s. The average of 200 consecutive traces is shown for each pharmacological condition. In control solution, on average, a significant facilitation of the second response was observed (i.e. the average amplitude of the second EPSPs was significantly (P < 0.05) larger than the one of the first EPSPs). In the presence of SP (which did not elicit direct effects in this MSN) the amplitude of the first EPSP was significantly increased (P < 0.001), the paired-pulse ratio was significantly (P < 0.05) decreased, and the amplitude of the second response became significantly (P < 0.05) smaller than the one of the first. B, average amplitude of the second EPSP (normalized to that of the first EPSP) for paired-pulse (50 ms interval) experiments in 5 MSNs recorded under current-clamp conditions, in control solution and in the presence of SP. C, in a different MSN, the same paired pulse protocol described for panel A was applied while an MSN was recorded under voltage-clamp conditions. Also in this case the average of 200 consecutive traces is shown for each pharmacological condition. In control solution, the second EPSC amplitude was significantly (P < 0.05) larger than that of the first EPSC. In the presence of SP, the amplitude of the first EPSC was significantly (P < 0.001) increased, the paired-pulse ratio decreased significantly (P < 0.05), and the amplitude of the second response became significantly (P < 0.05) smaller than the one of the first. No direct effects of SP were observed in this MSN. D, average amplitude of the second EPSC (normalized to that of the first EPSC) for paired-pulse (50 ms interval) experiments in 5 MSNs recorded under voltage-clamp conditions, in control solution and in the presence of SP.

Discussion

This is the first comprehensive study of the effects of SP on MSNs. We found that SP activates an inward-rectifying chloride conductance in a population of MSNs, and presynaptically facilitates glutamatergic responses in a different, but partially overlapping subpopulation of MSNs.

Postsynaptic effects of SP on MSNs

Overall, 59% of MSNs tested were directly modulated by exogenous SP. These effects (observed either as depolarizations or as inward currents) persisted in TTX, were mimicked by the NK1 receptor agonist SSP, and blocked by the NK1 receptor antagonist L-732,138, indicating that they were entirely mediated by postsynaptic NK1 receptors. Their time course was slow, often peaking > 15 min after a brief exposure, and they were invariably accompanied by decreased input resistance. This slow action contrasts with the fast one of GABA, which is coreleased with SP by MSNs of the direct pathway. Thus, the postsynaptic effects of SP, unlike those of GABA, are unlikely to affect MSNs on a subsecond time scale. The observed variability in the time course of SP and SSP effects may depend on the variable degree of intracellular dialysis caused by whole-cell recordings.

Our experiments also show that the action of SP was mediated by an increase in a chloride conductance. SP-induced currents displayed prominent inward rectification and reversed, on average, at −68 mV. This is more negative than the nominal reversal potential for chloride calculated with Nernst's equation based on external and internal solution composition (−51 mV); however, we and other authors (Koos & Tepper, 1999; Koos et al. 2004; Bracci & Panzeri, 2006) have found that the reversal potential for GABA receptors (which are mainly permeable to chloride) is substantially more negative than the nominal one in whole-cell recorded MSNs, suggesting that outward chloride transport mechanisms prevent complete chloride dialysis. Postsynaptic SP effects were completely blocked by zinc, which suppresses ClC-2 type inward rectifying currents (Kajita et al. 2000). Further evidence that strongly supports the idea that SP effects were mediated by a chloride conductance came from experiments with high- or low-chloride intracellular solution (containing caesium). With both solutions, MSNs depolarized spontaneously to levels between −30 and −40 mV, presumably as a result of potassium channel block by caesium (Calabresi et al. 1990; Nisenbaum & Wilson, 1995). When high-chloride internal solution was used (nominal ECl= 1 mV), SP responses were invariably depolarizing; conversely, while with low-chloride solution (nominal ECl=−91 mV), SP responses were hyperpolarizing. In resting MSNs recorded with standard intracellular solutions, the driving force for chloride is relatively small; this, together with the slow time course of SP effects, may explain why these effects have not been observed in a previous study (Aosaki & Kawaguchi, 1996). In another study, a minority of MSNs were found to be directly depolarized by SP, but the underlying ionic mechanisms were not investigated (Galarraga et al. 1999). Bath-application of either zinc or L-732,138 per se caused a slight hyperpolarization and an increase in input resistance in MSNs. This supports the notion that postsynaptic NK1 receptors were tonically activated, to some degree, by ambient levels of endogenous SP. As a result of this receptor activity, the chloride current activated by SP appeared to be moderately present in MSN in control solution, and contributing to MSN resting membrane potential and conductance. Consistent with this interpretation, pharmacological block of NK1 receptors, or of chloride channels by zinc, caused similar effects in MSNs.

Further studies will be required to identify the intracellular cascades linking NK1 receptor activation to activation of inward rectifying chloride conductances.

Effects of SP on glutamatergic responses

Decreased input resistance per se is expected to depress evoked EPSPs in current clamp experiments, due to membrane shunting (Banke & McBain, 2006). Nevertheless, exogenous SP facilitated EPSPs both in MSNs that were directly modulated by SP and in those that were not. In fact, despite the fact that decreased resistance may have masked potentiation of glutamate responses in some cases, SP-induced facilitation of glutamate responses was actually more frequent (73%) in MSNs that were also directly affected by SP than in the non-affected ones (among which facilitation was observed in 36% of cases). These experiments were carried out in the presence of GABAA, GABAB, opioid, D1, D2, nicotinic and muscarinic receptor antagonists; therefore we are confident that the evoked responses were purely glutamatergic, and that the effects of SP did not depend on any of these receptors.

The effects of SP on glutamatergic responses were accompanied by a marked decrease in paired-pulse ratio, often converting paired-pulse facilitation into depression. This indicates that SP acted presynaptically (Brenowitz & Trussell, 2001; Sippy et al. 2003), presumably through tachykinin receptors located on glutamatergic terminals. Pharmacological experiments clearly showed that, although NK1 receptors were mainly responsible for exogenous SP effects, a significant contribution of NK3 receptors was also present.

It is worth noting that while several presynaptic receptors have been found to inhibit glutamatergic transmission in the striatum (Nisenbaum et al. 1992; Gubellini et al. 2002; Pakhotin & Bracci, 2007; Tozzi et al. 2007), this is the first demonstration of a presynaptic facilitatory effect in this area.

Anatomical considerations

At least one anatomical substrate for the presynaptic effects of SP is straightforward, as NK1 receptors have been found on corticostriatal and thalamostriatal glutamatergic axonal terminals impinging on MSNs in the rat and monkey striatum (Jakab & Goldman-Rakic, 1996). How does endogenous SP reach these presynaptic receptors? SP-immunoreactive axon terminals arising from MSNs form synapses with spines and dendritic shafts of other MSNs (Bolam & Izzo, 1988; Yung et al. 1996). Corticostriatal and thalamostriatal terminals mainly synapse on dendritic spines (Jakab & Goldman-Rakic, 1996). Thus, extrasynaptic diffusion may allow synaptically released SP to reach NK1 receptors located on glutamatergic terminals, as hypothesized by Jakab & Goldman-Rakic (1996). NK3 receptors are also found in the striatum (Langlois et al. 2001), although their cellular localization has not been described. Our experiments on evoked potentials, carried out in the presence of dopamine and acetylcholine receptor antagonists, indicate that they are also localized presynaptically on glutamatergic terminals, whereby they facilitate transmitter release.

Another clear implication of the present results is that postsynaptic NK1 receptors must be present on MSNs. This is in apparent contrast to immunohistological studies that suggested that in the striatum postsynaptic NK1 receptors are selectively expressed by cholinergic and NOS-positive interneurons (Gerfen, 1991; Shigemoto et al. 1993; Jakab & Goldman-Rakic, 1996). A similar mismatch between histological and electrophysiological data exists for other neurons, which lack immunoreactivity for NK1 receptors, but respond to SP via receptors that show NK1-like pharmacological selectivity (Zhao et al. 1995, 1996; Baker et al. 2003). The reason for this discrepancy is probably due to the presence of a truncated variant of the NK1 receptor, which is widespread in the nervous system, including the basal ganglia (Baker et al. 2003; Caberlotto et al. 2003). This short isoform is not recognized by antibodies targeting the C-terminal of the receptor, but has pharmacological properties similar to the long isoform, and exhibits little desensitization (Jobling et al. 2001; Baker et al. 2003). The absence of desensitization when SP was repeatedly applied was indeed a distinctive feature of MSN responses to SP and SSP in the present study. Thus, it seems likely that MSN responses were mediated by a short variant of NK1 receptors. Further experiments using antibodies against the N-terminal of NK1 receptors will be required to validate this hypothesis.

What is the identity of the MSNs directly modulated by SP and of those in which SP facilitated glutamatergic responses? As mentioned above, there was partial overlap between these two populations; in particular, directly modulated MSNs were also substantially more likely to have their glutamatergic inputs facilitated. The main source of SP release in the striatum arises from MSNs belonging to the direct pathway (Yung et al. 1996; Wang et al. 2006). On the other hand, SP-immunoreactive terminals form synapses on dendrites of both direct and indirect pathway MSNs (Bolam & Izzo, 1988; Yung et al. 1996). Further study will be required to determine whether the MSNs affected by SP pre- or postsynaptically belong to a specific population with distinctive cytochemical features.

The dense local network of MSN axon collaterals is one of the salient anatomical features of the striatum, and GABAergic communication among MSNs has been extensively investigated with dual recordings (Tunstall et al. 2002; Koos et al. 2004). The present results suggest that MSNs may also use SP to facilitate excitatory inputs to other MSNs. This would be an effective form of excitatory communication among MSNs, and its coexistence with GABAergic inhibitory connections may endow the striatal networks with computationally rich architectures. The fact that groups of MSNs, perhaps receiving common or related cortical inputs, may cooperate through SP-mediated facilitation of their glutamatergic inputs could be particularly relevant for cortical pattern recognition; this is considered as one of the main tasks performed by the striatal networks (Bar-Gad et al. 2003). Clusters of SP-connected MSNs may compete, by means of GABAergic connections, for the ability to respond to different cortical contexts. Testing this hypothesis will require further investigation into the factors that determine the presence of SP-mediated connections among MSNs.

Glutamatergic terminals impinging on MSNs are also controlled by other presynaptic receptors, including GABAB, opioid and muscarinic ones. These receptors, which were pharmacologically blocked in the present study, can be activated under physiological conditions. Thus, whether net presynaptic facilitation or inhibition of glutamate release takes place will depend on a dynamic balance between the facilitatory action of NK1/NK3 receptors and the inhibitory action of the other presynaptic receptors.

Finally, SP-induced facilitation of glutamatergic responses is likely to favour the induction of long-term plasticity at corticostriatal synapses; in fact, such induction requires a strong activation of MSN glutamate receptors (Reynolds & Wickens, 2002; Gubellini et al. 2004; Surmeier et al. 2007), which in turn would be facilitated by activation of presynaptic NK1/NK3 receptors; this mechanism may enable SP-releasing MSNs to increase the responsiveness of other MSNs to cortical stimuli over a long time scale.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the Wellcome Trust and the Royal Society. We thank Dr Jon Turner for useful discussions.

References

- Almeida TA, Rojo J, Nieto PM, Pinto FM, Hernandez M, Martin JD, Candenas ML. Tachykinins and tachykinin receptors: structure and activity relationships. Curr Med Chem. 2004;11:2045–2081. doi: 10.2174/0929867043364748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aosaki T, Kawaguchi Y. Actions of substance P on rat neostriatal neurons in vitro. J Neurosci. 1996;16:5141–5153. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-16-05141.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker SJ, Morris JL, Gibbins IL. Cloning of a C-terminally truncated NK-1 receptor from guinea-pig nervous system. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2003;111:136–147. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(03)00002-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banke TG, McBain CJ. GABAergic input onto CA3 hippocampal interneurons remains shunting throughout development. J Neurosci. 2006;26:11720–11725. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2887-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bar-Gad I, Morris G, Bergman H. Information processing, dimensionality reduction and reinforcement learning in the basal ganglia. Prog Neurobiol. 2003;71:439–473. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2003.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaujouan JC, Torrens Y, Saffroy M, Kemel ML, Glowinski J. A 25 year adventure in the field of tachykinins. Peptides. 2004;25:339–357. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2004.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blomeley C, Bracci E. Excitatory effects of serotonin on rat striatal cholinergic interneurones. J Physiol. 2005;569:715–721. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.098269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolam JP, Hanley JJ, Booth PA, Bevan MD. Synaptic organisation of the basal ganglia. J Anat. 2000;196:527–542. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-7580.2000.19640527.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolam JP, Izzo PN. The postsynaptic targets of substance P-immunoreactive terminals in the rat neostriatum with particular reference to identified spiny striatonigral neurons. Exp Brain Res. 1988;70:361–377. doi: 10.1007/BF00248361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolam JP, Somogyi P, Takagi H, Fodor I, Smith AD. Localization of substance P-like immunoreactivity in neurons and nerve terminals in the neostriatum of the rat: a correlated light and electron microscopic study. J Neurocytol. 1983;12:325–344. doi: 10.1007/BF01148468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bracci E, Centonze D, Bernardi G, Calabresi P. Voltage-dependent membrane potential oscillations of rat striatal fast-spiking interneurons. J Physiol. 2003;549:121–130. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.040857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bracci E, Centonze D, Bernardi G, Calabresi P. Engagement of rat striatal neurons by cortical epileptiform activity investigated with paired recordings. J Neurophysiol. 2004;92:2725–2737. doi: 10.1152/jn.00585.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bracci E, Panzeri S. Excitatory GABAergic effects in striatal projection neurons. J Neurophysiol. 2006;95:1285–1290. doi: 10.1152/jn.00598.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenowitz S, Trussell LO. Minimizing synaptic depression by control of release probability. J Neurosci. 2001;21:1857–1867. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-06-01857.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caberlotto L, Hurd YL, Murdock P, Wahlin JP, Melotto S, Corsi M, Carletti R. Neurokinin 1 receptor and relative abundance of the short and long isoforms in the human brain. Eur J Neurosci. 2003;17:1736–1746. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02600.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calabresi P, Centonze D, Pisani A, Bernardi G. Endogenous adenosine mediates the presynaptic inhibition induced by aglycemia at corticostriatal synapses. J Neurosci. 1997;17:4509–4516. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-12-04509.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calabresi P, Mercuri NB, Bernardi G. Synaptic and intrinsic control of membrane excitability of neostriatal neurons. II. An in vitro analysis. J Neurophysiol. 1990;63:663–675. doi: 10.1152/jn.1990.63.4.663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark S, Jordt SE, Jentsch TJ, Mathie A. Characterization of the hyperpolarization-activated chloride current in dissociated rat sympathetic neurons. J Physiol. 1998;506:665–678. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.665bv.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galarraga E, Hernandez-Lopez S, Tapia D, Reyes A, Bargas J. Action of substance P (neurokinin-1) receptor activation on rat neostriatal projection neurons. Synapse. 1999;33:26–35. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2396(199907)33:1<26::AID-SYN3>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerfen CR. Substance P (neurokinin-1) receptor mRNA is selectively expressed in cholinergic neurons in the striatum and basal forebrain. Brain Res. 1991;556:165–170. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)90563-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerfen CR. The neostriatal mosaic: multiple levels of compartmental organization in the basal ganglia. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1992;15:285–320. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.15.030192.001441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graveland GA, DiFiglia M. The frequency and distribution of medium-sized neurons with indented nuclei in the primate and rodent neostriatum. Brain Res. 1985;327:307–311. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(85)91524-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graybiel AM. The basal ganglia: learning new tricks and loving it. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2005;15:638–644. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2005.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gubellini P, Picconi B, Bari M, Battista N, Calabresi P, Centonze D, Bernardi G, Finazzi-Agro A, Maccarrone M. Experimental parkinsonism alters endocannabinoid degradation: implications for striatal glutamatergic transmission. J Neurosci. 2002;22:6900–6907. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-16-06900.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gubellini P, Pisani A, Centonze D, Bernardi G, Calabresi P. Metabotropic glutamate receptors and striatal synaptic plasticity: implications for neurological diseases. Prog Neurobiol. 2004;74:271–300. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2004.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurney K, Prescott TJ, Wickens JR, Redgrave P. Computational models of the basal ganglia: from robots to membranes. Trends Neurosci. 2004;27:453–459. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2004.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakab RL, Goldman-Rakic P. Presynaptic and postsynaptic subcellular localization of substance P receptor immunoreactivity in the neostriatum of the rat and rhesus monkey (Macaca mulatta) J Comp Neurol. 1996;369:125–136. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19960520)369:1<125::AID-CNE9>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jobling P, Messenger JP, Gibbins IL. Differential expression of functionally identified and immunohistochemically identified NK1 receptors on sympathetic neurons. J Neurophysiol. 2001;85:1888–1898. doi: 10.1152/jn.2001.85.5.1888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kajita H, Whitwell C, Brown PD. Properties of the inward-rectifying Cl– channel in rat choroid plexus: regulation by intracellular messengers and inhibition by divalent cations. Pflugers Arch. 2000;440:933–940. doi: 10.1007/s004240000387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaneko T, Shigemoto R, Nakanishi S, Mizuno N. Substance P receptor-immunoreactive neurons in the rat neostriatum are segregated into somatostatinergic and cholinergic aspiny neurons. Brain Res. 1993;631:297–303. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(93)91548-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kincaid AE, Zheng T, Wilson CJ. Connectivity and convergence of single corticostriatal axons. J Neurosci. 1998;18:4722–4731. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-12-04722.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kita T, Kita H, Kitai ST. Passive electrical membrane properties of rat neostriatal neurons in an in vitro slice preparation. Brain Res. 1984;300:129–139. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(84)91347-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koos T, Tepper JM. Inhibitory control of neostriatal projection neurons by GABAergic interneurons. Nat Neurosci. 1999;2:467–472. doi: 10.1038/8138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koos T, Tepper JM, Wilson CJ. Comparison of IPSCs evoked by spiny and fast-spiking neurons in the neostriatum. J Neurosci. 2004;24:7916–7922. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2163-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langlois X, Wintmolders C, te Riele P, Leysen JE, Jurzak M. Detailed distribution of Neurokinin 3 receptors in the rat, guinea pig and gerbil brain: a comparative autoradiographic study. Neuropharmacology. 2001;40:242–253. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(00)00149-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manabe T, Wyllie DJ, Perkel DJ, Nicoll RA. Modulation of synaptic transmission and long-term potentiation: effects on paired pulse facilitation and EPSC variance in the CA1 region of the hippocampus. J Neurophysiol. 1993;70:1451–1459. doi: 10.1152/jn.1993.70.4.1451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nisenbaum ES, Berger TW, Grace AA. Presynaptic modulation by GABAB receptors of glutamatergic excitation and GABAergic inhibition of neostriatal neurons. J Neurophysiol. 1992;67:477–481. doi: 10.1152/jn.1992.67.2.477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nisenbaum ES, Wilson CJ. Potassium currents responsible for inward and outward rectification in rat neostriatal spiny projection neurons. J Neurosci. 1995;15:4449–4463. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-06-04449.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pakhotin P, Bracci E. Cholinergic interneurons control the excitatory input to the striatum. J Neurosci. 2007;27:391–400. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3709-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preston Z, Richardson PJ, Pinnock RD, Lee K. NK-3 receptors are expressed on mouse striatal gamma-aminobutyric acid-ergic interneurones and evoke [3H] g-aminobutyric acid release. Neurosci Lett. 2000;284:89–92. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(00)00968-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quitadamo C, Fabbretti E, Lamanauskas N, Nistri A. Activation and desensitization of neuronal nicotinic receptors modulate glutamatergic transmission on neonatal rat hypoglossal motoneurons. Eur J Neurosci. 2005;22:2723–2734. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04460.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds JN, Wickens JR. Dopamine-dependent plasticity of corticostriatal synapses. Neural Netw. 2002;15:507–521. doi: 10.1016/s0893-6080(02)00045-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz PE, Cook EP, Johnston D. Changes in paired-pulse facilitation suggest presynaptic involvement in long-term potentiation. J Neurosci. 1994;14:5325–5337. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-09-05325.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shigemoto R, Nakaya Y, Nomura S, Ogawa-Meguro R, Ohishi H, Kaneko T, Nakanishi S, Mizuno N. Immunocytochemical localization of rat substance P receptor in the striatum. Neurosci Lett. 1993;153:157–160. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(93)90311-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sippy T, Cruz-Martin A, Jeromin A, Schweizer FE. Acute changes in short-term plasticity at synapses with elevated levels of neuronal calcium sensor-1. Nat Neurosci. 2003;6:1031–1038. doi: 10.1038/nn1117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somogyi P, Bolam JP, Smith AD. Monosynaptic cortical input and local axon collaterals of identified striatonigral neurons. A light and electron microscopic study using the Golgi-peroxidase transport-degeneration procedure. J Comp Neurol. 1981;195:567–584. doi: 10.1002/cne.901950403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoessl AJ. Localization of striatal and nigral tachykinin receptors in the rat. Brain Res. 1994;646:13–18. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)90052-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surmeier DJ, Ding J, Day M, Wang Z, Shen W. D1 and D2 dopamine-receptor modulation of striatal glutamatergic signaling in striatal medium spiny neurons. Trends Neurosci. 2007;30:228–235. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2007.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taverna S, van Dongen YC, Groenewegen HJ, Pennartz CM. Direct physiological evidence for synaptic connectivity between medium-sized spiny neurons in rat nucleus accumbens in situ. J Neurophysiol. 2004;91:1111–1121. doi: 10.1152/jn.00892.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tepper JM, Koos T, Wilson CJ. GABAergic microcircuits in the neostriatum. Trends Neurosci. 2004;27:662–669. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2004.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tozzi A, Tscherter A, Belcastro V, Tantucci M, Costa C, Picconi B, Centonze D, Calabresi P, Borsini F. Interaction of A2A adenosine and D2 dopamine receptors modulates corticostriatal glutamatergic transmission. Neuropharmacology. 2007;53:783–789. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2007.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tunstall MJ, Oorschot DE, Kean A, Wickens JR. Inhibitory interactions between spiny projection neurons in the rat striatum. J Neurophysiol. 2002;88:1263–1269. doi: 10.1152/jn.2002.88.3.1263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Kai L, Day M, Ronesi J, Yin HH, Ding J, Tkatch T, Lovinger DM, Surmeier DJ. Dopaminergic control of corticostriatal long-term synaptic depression in medium spiny neurons is mediated by cholinergic interneurons. Neuron. 2006;50:443–452. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson CJ, Groves PM. Fine structure and synaptic connections of the common spiny neuron of the rat neostriatum: a study employing intracellular inject of horseradish peroxidase. J Comp Neurol. 1980;194:599–615. doi: 10.1002/cne.901940308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yung KK, Smith AD, Levey AI, Bolam JP. Synaptic connections between spiny neurons of the direct and indirect pathways in the neostriatum of the rat: evidence from dopamine receptor and neuropeptide immunostaining. Eur J Neurosci. 1996;8:861–869. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1996.tb01573.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao FY, Saito K, Yoshioka K, Guo JZ, Murakoshi T, Konishi S, Otsuka M. Subtypes of tachykinin receptors on tonic and phasic neurones in coeliac ganglion of the guinea-pig. Br J Pharmacol. 1995;115:25–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1995.tb16315.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao FY, Saito K, Yoshioka K, Guo JZ, Murakoshi T, Konishi S, Otsuka M. Tachykininergic synaptic transmission in the coeliac ganglion of the guinea-pig. Br J Pharmacol. 1996;118:2059–2066. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15644.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]