Abstract

Objective

To assess developmental trends in physical activity and sedentary behaviour in British adolescents in relation to sex, ethnicity and socioeconomic status (SES).

Design

A 5‐year longitudinal study of a diverse cohort of students aged 11–12 years at baseline in 1999.

Setting

36 London schools sampled using a stratified random sampling procedure.

Participants

A total of 5863 students categorised as white, black or Asian, and stratified for SES using the Townsend Index.

Main outcome measures

Number of days per week of vigorous activity leading to sweating and breathing hard. Hours of sedentary behaviour, including watching television and playing video games. Data were analysed using multilevel, linear, mixed models.

Results

Marked reductions in physical activity and increases in sedentary behaviour were noticed between ages 11–12 and 15–16 years. Boys were more active than girls, and the decline in physical activity was greater in girls (46% reduction) than in boys (23%). Asian students were less active than whites, and this was also true of black girls but not boys. Black students were more sedentary than white students. Levels of sedentary behaviour were greater in respondents from lower SES. Most differences between ethnic and SES groups were present at age 11 years, and did not evolve over the teenage years.

Conclusions

Physical activity declines and sedentary behaviour becomes more common during adolescence. Ethnic and SES differences are observed in physical activity and sedentary behaviour in British youth that anticipate adult variations in adiposity and cardiovascular disease risk. These are largely established by age 11–12 years, so reversing these patterns requires earlier intervention.

A widespread concern exists about the low levels of vigorous physical activity and high rates of sedentary behaviour in adolescents.1,2 Cross‐sectional studies indicate that physical activity declines and sedentary behaviour becomes more common between ages 10–12 years and later teenage years.3,4,5 Physical activity in youth is a predictor of subsequent adiposity,6 and decreases in physical activity over the teenage years are associated with increases in body mass index (BMI).7 Longitudinal studies have confirmed the decline in physical activity in samples in the US,8,9 but there have been no large‐scale longitudinal studies of changes in physical activity and sedentary behaviour in British youth and only two in Europe.10,11 Important differences in physical activity in adults are related to ethnicity and socioeconomic status (SES), but it is not known at what age these emerge.9,12 This analysis of the Health and Behaviour in Teenagers Study investigated trends in physical activity and sedentary behaviour between ages 11–12 and 15–16 years in an ethnically and socioeconomically diverse sample of school students.

Participants and methods

The Health and Behaviour in Teenagers Study was carried out in 36 secondary schools randomly selected from all schools in 13 boroughs of South London, stratified by school type (inner London state schools, outer London state schools and independent schools; single sex or mixed) to obtain an ethnically and socioeconomically diverse sample. The first wave of data was collected in 1999 from students in year 7 (age 11–12 years, US grade 6) and continued annually until year 11 (age 15–16 years). All students registered in the relevant year were eligible to take part in the study. We sent information about the study to parents, giving them the opportunity to exclude their child from participation, and all students gave written consent. The study was approved by the University College London/University College London Hospital Medical Ethics Committee.

Trained researchers visited the schools every year and explained the purpose of the study. Students completed self‐report questionnaires, with assistance available as required, and anthropometric measures were taken as described previously.13 Ethnicity information was obtained by self‐report, and classified into white, black or mixed black, Asian or mixed Asian, and other. The “other” ethnic group was too small to divide into specific subgroups, and hence excluded from analyses. SES was defined using an area‐based measure, the Townsend Index, derived from postal code information. The Townsend Index is standardised across England and Wales, with positive values indicating high socioeconomic deprivation and negative values below‐average deprivation. Townsend scores were divided into tertiles for analysis.

We assessed vigorous physical activity by asking students on how many of the past 7 days they had carried out vigorous exercise that made them sweat and breathe hard.14 Responses were coded from no days (0) to every day (7). We measured sedentary behaviour by asking students how many hours they watched television, or played computer or video games on school days and weekends. Responses were added to generate an estimate of total hours of sedentary behaviour, as used in other investigations.15

Statistical analysis

We analysed changes in physical activity and sedentary behaviour using multilevel, linear, mixed‐model analyses in the Centre for Multilevel Modelling (MLwiN; University of Bristol), with student, year of assessment and school at levels 1, 2 and 3, respectively. The dependent variables were days per week of vigorous physical activity and hours per week of sedentary behaviour. The data were weighted at the school level according to inverse sampling probability based on school type. The mixed‐models analysis fits a linear trend line for each student and does not require data for every year, maximising the use of available data. Townsend Index scores were divided into tertiles for analyses by SES.

Results

We recruited 4320 (84%) of year 7 students registered in the schools into the study. Table 1 summarises their characteristics. In later years, additional students participated either because they were new to the school or had previously been absent, so a total of 5863 students took part in ⩾1 years. Response rates were >80% in the first 4 years, with 1.5%–5.6% of students declining to take part, and a further 10–16% being absent when their class was assessed. In the final year, two schools were unable to continue and some students had examinations or placement leave, reducing the participation rate to 78%. Overall, 36% completed 5 years, 58% completed ⩾4 years, 73% completed ⩾3 years and 88% completed at least 2 years. Ethnic information was not available for 159 students (2.7%), 113 (1.9%) had missing data on postal code and 33 (0.6%) students did not provide data on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. The remaining 5287 students were included in the analyses.

Table 1 Age, ethnicity and socioeconomic status of the sample by sex.

| Boys | Girls | |

|---|---|---|

| Total sample (n) | 2577 | 1742 |

| Mean (SD) age (years) | 11.81 (0.36) | 11.84 (0.32) |

| Mean (SD) body mass index (kg/m2) | 19.03 (3.37) | 19.98 (3.82) |

| Ethnic group, n (%) | ||

| White | 1597 (65.7) | 1010 (61.6) |

| Black and mixed black | 582 (23.9) | 454 (27.7) |

| Asian and mixed Asian | 253 (10.4) | 175 (10.7) |

| Townsend Index (Mean (SD)) | ||

| Higher | 877 (34.4) | 555 (32.1) |

| Intermediate | 775 (30.4) | 462 (26.8) |

| Lower | 898 (35.2) | 710 (41.1) |

Physical activity trends over time

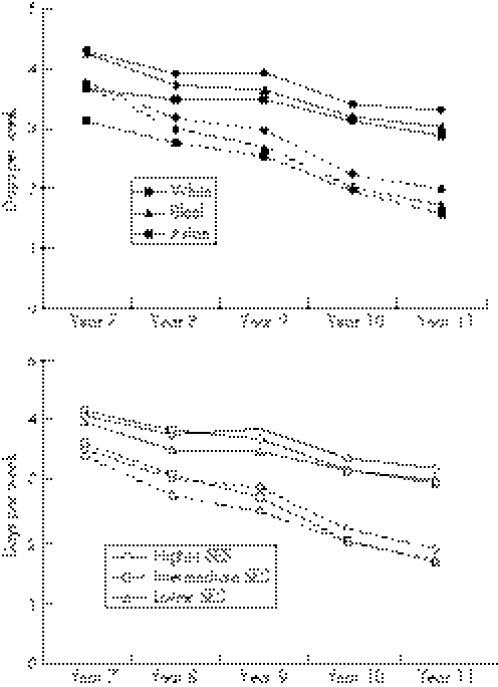

Boys consistently reported more physical activity than girls, hence separate models were constructed, simultaneously evaluating associations with ethnicity and SES in the trends across the five time points. Figure 1 shows the levels of vigorous physical activity separately by sex. We observed a fall in the mean number of days of vigorous physical activity per week in boys (–1.06 days, SE 0.068) and girls (–1.82 days, SE 0.072) over the course of the study (p<0.001). On average, boys exercised 0.99 (SE 0.043) days per week more than girls (p<0.001). There was an interaction between sex and school year, with a steeper average decline in girls than in boys (mean 0.46 days (SE 0.018) and 0.25 days (SE 0.016) per week per year (SE 0.018); p<0.001). Asian students were less physically active than white students (p<0.001); Asian girls exercised on average 0.45 days per week less (SE 0.101) and Asian boys 0.46 days less (SE 0.018) than their white counterparts. The disparity between white and Asian girls diminished by 0.11 days a week per year (SE 0.046, p<0.05). Black girls averaged 0.39 days a week (SE 0.122, p<0.001) less physical activity than white students, which did not change over time, although white and black boys did not differ in physical activity levels or trends.

Figure 1 Average number of days per week of vigorous physical activity over the five years, divided on the basis of ethnicity (adjusted for socioeconomic status (SES), upper panel) and SES (adjusted for ethnicity and lower panel). Figures are also adjusted for school clustering and inverse sampling probability according to school type. Boys are shown as solid lines and girls as dashed lines.

There was no association between SES and physical activity in boys, but girls from lower SES were less active (p<0.001). The mean difference between the highest and lowest SES tertiles averaged 0.47 days (SE 0.049), but SES effects did not vary across the 5 years of investigation.

Trends in sedentary behaviour

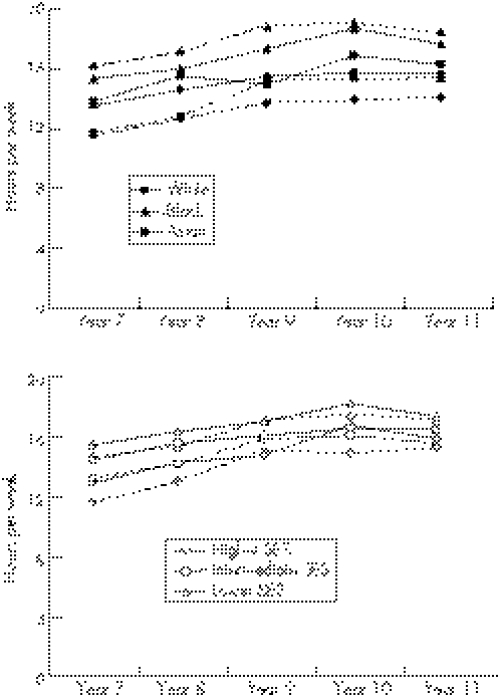

Boys reported more hours of sedentary behaviour than girls throughout the study (mean difference 0.63, SE 0.254, p<0.01), with no divergence in trends over time. Figure 2 shows the levels of sedentary behaviour. Hours of sedentary behaviour increased in all groups over the 5 years, with an average increase of 2.52 h (SE 0.066) per week in boys and 2.81 h (SE 0.081) per week in girls (p<0.001). Black students of both sexes reported higher levels of sedentary behaviour than their white peers. The difference averaged 2.76 h (SE 0.562) in boys and 5.4 h (SE 0.474) in girls. This difference did not vary over the 5 years of the study. Trends in sedentary behaviour also differed in white and Asian girls (p<0.05); there was no difference in year 7, but the increase in sedentary behaviour was faster in Asian girls, with an average difference in rates of 0.41 (SE 0.197) h each day.

Figure 2 Average number of hours per week of sedentary behaviour over the five school years, divided on the basis of ethnicity (adjusted for socioeconomic status (SES), upper panel) and SES (adjusted for ethnicity, lower panel). Figures are also adjusted for school clustering and inverse sampling probability according to school type. Boys are shown as solid lines and girls as dashed lines.

Sedentary behaviour levels were greater in students from lower SES neighbourhoods (p<0.001). The difference between the higher and lower SES groups averaged 2.29 (SE 0.318) h per week in boys and 4.09 (SE 0.49) h per week in girls. This difference did not change over the 5 years of the study.

Discussion

This is the first study to track trends in physical activity and sedentary behaviour over early teenage years in a large sample of British adolescents. These years are crucial because they represent the emergence of more independent, adult patterns of behaviour after relatively stable levels in earlier childhood.16 Our data indicate that vigorous physical activity decreases and hours spent in sedentary behaviour increase between the ages of 11–12 and 15–16 years, with a larger decline in physical activity in girls than in boys. Asian students are less physically active than white boys and girls, whereas sedentary behaviours are higher in black students. Students from lower SES neighbourhoods report higher levels of sedentary behaviour, and girls from lower SES, but not boys, are less physically active than those from more affluent backgrounds.

Developmental trends in physical activity and sedentary behaviour

The decline in the number of days per week of vigorous physical activity was striking in all groups. In the white population, days of physical activity fell by 23% in boys and by 46% in girls over the 5 years of the study. Cross‐sectional studies in the UK have shown inconsistent associations between age and physical activity in youth. A reduction in physical activity has been found in girls, but no decrease between ages 11 and 15 years was recorded in boys in the Health Survey for England5 or in the Scottish Health Behaviour of School‐aged Children Study.17 Longitudinal studies have the advantage of avoiding selection factors influencing the participation of younger and older students, and of eliminating secular trends in physical activity and leisure habits that might affect young people of different ages, while also permitting associations between physical activity and later health risk to be analysed.7 Other recent longitudinal studies have reported decreases in physical activity over early teenage years in both boys and girls.8,9,10,11 We observed a far greater decline in vigorous physical activity in girls than in boys, the opposite of the pattern found in samples from other countries.8,10,11 Differences in the measurement of physical activity make direct comparison impossible, but our findings are consistent with data from the Health Survey for England.5

Sedentary behaviour represents a distinct category, and is not simply the absence of vigorous exercise. Sedentary behaviour and physical activity are only modestly correlated, have separate sociodemographic determinants and are associated differently with subsequent health risk.14,18 Slightly higher levels of sedentary behaviour were reported in boys than in girls, as was found in the 1997 National Diet and Nutrition Survey,16 but the increase over adolescent years in girls was greater. Sedentary behaviours are thought to have a dual role in promoting obesity, as they not only involve low energy expenditure, but may also be associated with intake of high‐energy snacks.

Ethnic differences

We observed pronounced differences in physical activity between white and Asian students throughout the study. In addition, Asian girls showed a faster increase in sedentary behaviour between ages 12–13 and 15–16 years than white girls (fig 3). Adults of Indian, Pakistani and Bangladeshi origin are less physically active than the white population, with particularly low participation rates in sports and exercise.12 This difference is associated with higher levels of abdominal adiposity and increased risk of coronary heart disease and diabetes. Sedentary behaviour was also more common in black than in white students, and black girls engaged in less physical activity than white girls. Obesity levels are substantially higher in black African and black Caribbean women than in white women in the UK. Comparisons in the US also indicate lower physical activity in black than white adolescents.9,19 The differences that we observed in physical activity and sedentary behaviour may therefore contribute to later morbidity and health risk. However, our finding that ethnic differences were present at age 11–12 years indicates the need to study younger children in order to identify the emergence of these patterns.

Socioeconomic factors

Some uncertainties surround SES differences in physical activity; men and women from higher SES are involved in more sport and recreational activity, but are less active at work.20 Cross‐sectional studies in the UK show less physical activity in adolescents from lower socioeconomic backgrounds,12,17 and Kimm et al9 reported larger decreases over time in girls from lower SES backgrounds in the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute Growth and Health Study. We found SES differences in physical activity in girls but not in boys, and differences in sedentary behaviour in both sexes. Sedentary behaviour may be important to future health in view of the associations that have been described between sedentary behaviour, such as television viewing and adiposity.21 However, the nature of the sedentary activity may be important, and some adolescents combine activities such as computer gaming with active pursuits.

What is already known on this topic

Adolescence is a phase during which physical activity decreases, although cross‐sectional surveys in the UK show an inconsistent pattern.

Sedentary behaviour is a distinct category of activity and is not merely the absence of vigorous exercise.

Physical activity in youth is a predictor of later adiposity.

Variations in physical activity in UK adolescents in relation to ethnic background and socioeconomic status are poorly understood,

What this study adds

There is a decrease in vigorous activity and increase in sedentary behaviour between ages 11–12 and 15–16 years.

Adolescents of lower socioeconomic status (SES) engage in more sedentary behaviour, but physical activity differs by SES only in girls.

Physical activity is lower in Asian than in white adolescents, whereas black adolescents report higher levels of sedentary behaviour.

Ethnic and SES differences are largely established by age 11–12 years, hence remedial action requires earlier intervention.

Limitations

Physical activity was assessed with relatively simple questions about the number of days of activity in the past week, rather than the duration or type of activity. Sallis and Owen22 have argued that self‐report measures in children aged 11–12 years are more reliable when assessments are simple and involve recall over a short period, and we were concerned that recall of frequency and duration would be too challenging. The measure of sedentary behaviour was similar to that used previously,15,18 but is likely to have led to underestimation in comparison with diary and ecological sampling techniques.16

Conclusions

This study confirms the trend towards reduced physical activity and increased sedentary behaviour over early teenage years in a longitudinal analysis of British students. Important ethnic and socioeconomic differences anticipate adult variations of adiposity and cardiovascular disease risk. Social and cultural factors contribute to these patterns, although inequalities in the environment are also relevant.23 Differences by ethnic group and SES were largely established in the first wave of data collection when participants were aged 11–12 years. Objective measures of physical activity do not show differences by SES in children aged around 4 years,24 suggesting that the primary school years may be critical for the development of disparities in physical activity and sedentary behaviour. Timetabled physical education makes a relatively minor contribution,25 hence more general society‐wide changes in family recreational habits are required if ethnic minority and lower SES groups are not to be disadvantaged.

Acknowledgements

We thank the 36 schools for their participation and those involved in collecting the data for their effort.

Abbreviations

SES - socioeconomic status

Footnotes

Funding: This research was supported by Cancer Research UK, which had no involvement in the study itself or its interpretation. AS was supported by the British Heart Foundation.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: The study was approved by the University College London/University College London Hospital Medical Ethics Committee.

Contributors: JW and NHB were involved in the conception and design of the study. Data were analysed by NHB, DRB and AS. AS and NHB wrote the manuscript, and JW and DRB were involved in revising the manuscript. JW is the guarantor.

References

- 1.Chief Medical Officer At least five a week: evidence on the impact of physical activity and its relationship to health. London, UK: The Stationery Office, 2004

- 2.Department of Health and Human Services Promoting better health for young people through physical activity and sports: a report to the President from the Secretary of Health and Human Services and the Secretary of Education. Washington, DC: Department of Health and Human Services, 2000

- 3.Kristjansdottir G, Vilhjalmsson R. Sociodemographic differences in patterns of sedentary and physically active behavior in older children and adolescents. Acta Paediatr 200190429–435. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Caspersen C J, Pereira M A, Curran K M. Changes in physical activity patterns in the United States, by sex and cross‐sectional age. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2000321601–1609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sproston K, Primatesta P. eds. Health Survey for England 2002: the health of children and young poeple. London, UK: The Stationery Office, 2003

- 6.Must A, Tybor D J. Physical activity and sedentary behavior: a review of longitudinal studies of weight and adiposity in youth. Int J Obes 200529(Suppl 2)S84–S96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kimm S Y, Glynn N W, Obarzanek E.et al Relation between the changes in physical activity and body‐mass index during adolescence: a multicentre longitudinal study. Lancet 2005366301–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aaron D J, Storti K L, Robertson R J.et al Longitudinal study of the number and choice of leisure time physical activities from mid to late adolescence: implications for school curricula and community recreation programs. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 20021561075–1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kimm S Y, Glynn N W, Kriska A M.et al Decline in physical activity in black girls and white girls during adolescence. N Engl J Med 2002347709–715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Telama R, Yang X. Decline of physical activity from youth to young adulthood in Finland. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2000321617–1622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van Mechelen W, Twisk J W, Post G B.et al Physical activity of young people: the Amsterdam Longitudinal Growth and Health Study. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2000321610–1616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sproston K, Mindell J.Health Survey for England 2004: the health of ethnic minority groups. London: The Stationery Office, 2006

- 13.Wardle J, Henning Brodersen N, Cole T J.et al Development of adiposity in adolescence: five year longitudinal study of an ethnically and socioeconomically diverse sample of young people in Britain. BMJ 20063321130–1135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Henning Brodersen N, Steptoe A, Williamson S.et al Sociodemographic, developmental, environmental, and psychological correlates of physical activity and sedentary behavior at age 11 to 12. Ann Behav Med 2005292–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Robinson T N, Hammer L D, Killen J D.et al Does television viewing increase obesity and reduce physical activity? Cross‐sectional and longitudinal analyses among adolescent girls. Pediatrics 199391273–280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gregory J, Lowe S.National Diet and Nutrition Survey: young people aged 4 to 18 years. London, UK: The Stationery Office, 2000

- 17.Inchley J C, Currie D B, Todd J M.et al Persistent socio‐demographic differences in physical activity among Scottish schoolchildren 1990‐2002. Eur J Public Health 200515386–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Biddle S J, Gorely T, Marshall S J.et al Physical activity and sedentary behaviours in youth: issues and controversies. J R Soc Health 200412429–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bradley C B, McMurray R G, Harrell J S.et al Changes in common activities of 3rd through 10th graders: the CHIC study. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2000322071–2078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Macintyre S, Mutrie N. Socio‐economic differences in cardiovascular disease and physical activity: stereotypes and reality. J R Soc Health 200412466–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marshall S J, Biddle S J, Gorely T.et al Relationships between media use, body fatness and physical activity in children and youth: a meta‐analysis. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 2004281238–1246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sallis J F, Owen N.Physical activity and behavioralmMedicine. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 1999

- 23.Gordon‐Larsen P, Nelson M C, Page P.et al Inequality in the built environment underlies key health disparities in physical activity and obesity. Pediatrics 2006117417–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kelly L A, Reilly J J, Fisher A.et al Effect of socioeconomic status on objectively measured physical activity. Arch Dis Child 20069135–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mallam K M, Metcalf B S, Kirkby J.et al Contribution of timetabled physical education to total physical activity in primary school children: cross sectional study. BMJ 2003327592–593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]