Abstract

Measuring socioeconomic position (SEP) in population chronic disease and risk factor surveillance systems is essential for monitoring socioeconomic inequalities in health over time. Life‐course measures are an innovative way to supplement other SEP indicators in surveillance systems. A literature review examined the indicators of early‐life SEP that could potentially be used in population health surveillance systems. The criteria of validity, relevance, reliability and deconstruction were used to determine the value of potential indicators. Early‐life SEP indicators used in cross‐sectional and longitudinal studies included education level, income, occupation, living conditions, family structure and residential mobility. Indicators of early‐life SEP should be used in routine population health surveillance to monitor trends in the health and SEP of populations over time, and to analyse long‐term effects of policies on the changing health of populations. However, these indicators need to be feasible to measure retrospectively, and relevant to the historical, geographical and sociocultural context in which the surveillance system is operating.

Chronic disease and risk factor surveillance systems collect information on populations to monitor health and its determinants. Determinants of health in surveillance systems in recent decades have traditionally been confined to behavioural risk factors such as cigarette smoking, physical inactivity and poor diet. More recently, with increased recognition that inequalities in health are associated with social, economic and environmental factors in addition to behavioural factors,1,2,3,4,5 more emphasis has been placed on measurement of socioeconomic position (SEP).6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14 We use SEP in this paper, rather than socioeconomic status or social class, as it encompasses the material and social resources that influence the position that people hold in societies.10,15 A life‐course approach, which includes indicators of early‐life social circumstances, adds value to the measurement of SEP in surveillance systems.

Although it is recognised that comprehensive population health surveillance systems use data from a wide range of sources, including census data, mortality data and hospital statistics,16 population surveys are the focus of this paper. Surveillance is characterised by continuous data collection17 in repeated, independent, cross‐sectional surveys. Its strength lies in its ability to provide trend data on the health of populations over time, and the intelligence about population groups that disproportionately experience certain health‐related problems, while suggesting a basis for public health action.18,19,20

Measuring SEP in population health surveillance systems enables informed decisions to be made about the design, evaluation and monitoring of policies and interventions dealing with inequalities.9,21,22 Continuing to refine methods of identifying and measuring risk factors for chronic diseases is valuable for understanding disease aetiology23,24 and devising strategies other than those based on behaviour change to modify population risks. Epidemiological analysis of socioeconomic inequalities in health, including their change over time, requires improved measures of SEP in public health surveillance.16,25

Traditionally, surveillance systems measure the current SEP of respondents at the time the survey is conducted. The cumulative and dynamic nature of socioeconomic structures and experiences is more likely to be captured using a life‐course approach,8 which examines the long‐term effects on health and disease of physical and social exposures during gestation, childhood, adolescence, young adulthood and later adult life.26 It includes study of the biological, behavioural and psychosocial pathways that operate across a person's life course, as well as across generations, to influence health status. Life‐course effects refer to how health status at any given age reflects not only contemporary conditions but also prior living circumstances for a given birth cohort, from conception onwards.27 Several interrelated conceptual models of life‐course influences on health in adulthood exist (table 1),28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41 including the critical period, pathway and cumulative theories.

Table 1 Life‐course models explaining the association between early‐life circumstances and health in adulthood.

| Model | Description |

|---|---|

| Critical period | This model implies that there is a period of development in early life during which exposures to deprivation have long‐term effects on adult health, independent of adult circumstances28,29—for example, the fetal origins of disease hypothesis.30,31 |

| Pathway | The early‐life environment sets people on life trajectories or directions that in turn affect health status over time and into adulthood.32,33,34 The pathway model views early environment to be important, but only because it shapes and influences the socioeconomic trajectories of people.35 Circumstances in early life are seen as the initial stage in the pathway to adult health but with an indirect effect, influencing adult health through social trajectories such as restricting educational opportunities, thus influencing socioeconomic circumstances and health in later life.34 |

| Cumulative | The intensity and duration of exposure to unfavourable or favourable physical and social environments throughout life affects health status in a dose–response fashion.36,37,38,39,40 Unfavourable circumstances throughout life are associated with the greatest risk of poor health in adulthood, whereas unfavourable circumstances at only one stage of life may be lessened by improved circumstances at another stage.34 This accumulation of risk approach emphasises both biological and social experiences in childhood, adolescence and early adulthood, and how these biological and social risk factors combine and form pathways between early‐life experiences and adult disease.41 |

If health status observed in adulthood is the result of social and biological factors that have evolved over the life course,42 measuring SEP at only one stage of life is inadequate to explain fully the contributions of socioeconomic factors to health status37 and how these change over time. Indicators of SEP over the life course, particularly during early life, therefore need to be included in population health surveillance systems. The challenge remaining is to determine which specific indicators of socioeconomic circumstances at birth, through childhood, adolescence and young adulthood, should be included. Several reviews have provided detailed discussion of indicators of SEP, including their strengths and limitations, and the theoretical basis of the constructs they intend to measure.15,43,44,45,46 This paper aims to position population health surveillance within the literature of SEP and health over the life course. It reviews indicators of early‐life SEP that have been used previously in longitudinal and cross‐sectional studies, and examines their potential value for use in population health surveillance systems.

Methods

A review of the literature was conducted to identify studies that examine the association of indicators of SEP during early life with health over the life course. Early life was defined as the period from birth, through childhood, adolescence and young adulthood.

Search strategy

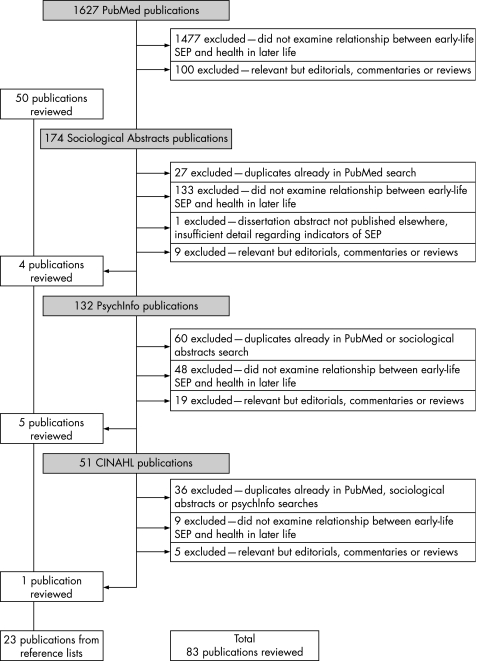

PubMed, CINAHL, PsychInfo and Sociological Abstracts electronic databases were used to search for the international literature. The terms “life course” or “lifecourse” in addition to the MeSH headings of “socioeconomic factors”, “socioeconomic status” and “social class” were searched for in titles and abstracts. The search was restricted to studies on humans, published in the English language. Reference lists of included studies were hand searched for publications potentially missed in electronic searches. Searches were conducted from the starting of the databases, and no studies were excluded based on study design or the specific life‐course model used. The searches resulted in some studies being extracted that examined health over the life course but did not measure SEP during early life. Figure 1 shows results of the database searches, as at March 2005. A list of excluded studies is available from the corresponding author on request.

Figure 1 Results of literature searches.

Assessment of the studies

The indicators of early‐life SEP that were used in the included studies were assessed according to whether they were measured prospectively or relied on retrospective recall in either cross‐sectional or longitudinal designs. The potential value of indicators for use in surveillance systems was assessed against criteria based on previous work on the value of public health indicators.47 Specifically, in terms of validity, indicators were assessed according to whether they had a sound theoretical base for inclusion in surveillance systems, whether they measured what they were designed to measure, whether they were associated with other indicators measuring the same construct and whether they predicted what was expected in terms of health outcomes. Indicators of SEP were also assessed for their relevance in different times, places and cultures, the feasibility of measuring them in surveillance systems that necessarily rely on retrospective recall and their ability to be measured consistently over time (reliability). Summary indicators assembled from more than one individual indicator were also assessed for their ability to be deconstructed into their component parts (deconstruction).

Results

Figure 1 shows details of the number of studies obtained from each database. Date of publication of the 83 included studies ranged from April 199248 to January 2005.49,50 Multiple publications from the same study meant that 45 separate studies were included in the 83 publications reviewed.

Indicators of early‐life SEP were grouped into six categories (education level, income, occupation, living conditions, family structure and residential mobility) that reflected experiences from birth through childhood, adolescence and early adulthood (tables 2–7).51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116,117,118,119,120,121,122,123,124,125,126,127,128,129 Whereas cross‐sectional studies always relied on retrospective recall, some longitudinal studies also collected early‐life SEP information retrospectively.

Table 2 Early‐life indicators of education.

| Indicator | Location, study design | Indicators of SEP measured | Criteria |

|---|---|---|---|

| Highest education level of paternal and maternal grandmother | Danish 1958 cohort of men51 | P | Validity: Education of paents is less likely to change after young adulthood than their occupation or income Low educational level of the mother is an important childhood characteristic in explaining socioeconomic inequalities in health56Relevance: Relationship between education and health exists almost universally Norms and social meanings of education change over time and are different between population groups and cultures6Reliability:Potentially affected by recall bias Education level of parents is a relatively stable indicator of SEPDeconstruction: Not applicable |

| Highest education level of father | 1958 British Birth Cohort52 | P | |

| USA, Longitudinal Alameda County Study53 | R | ||

| USA, Cross‐sectional National Survey of Midlife Development54 | R | ||

| USA, Longitudinal Normative Aging Study55 | R | ||

| Highest education level of mother | Australia, Longitudinal Mater—University of Queensland Study of Pregnancy and its Outcomes48,57 | P | |

| Danish 1958 cohort of men51 | P | ||

| The Netherlands, Longitudinal Study of Socio‐Economic Health Differences58 | R | ||

| USA, Cross‐sectional National Survey of Midlife Development54 | R | ||

| Mother's education when participant born and aged 7 years | USA, Longitudinal National Collaborative Perinatal Project59,60 | P | |

| Highest education level of parents | Slovakia, Cross‐sectional survey of adolescents61 | P | |

| USA, Longitudinal CARDIA Study62 | R | ||

| USA, Cross‐sectional, Midwestern Public School Survey49 | R | ||

| USA, Longitudinal National Survey of Children63 | P | ||

| Mother's and father's education level when participant aged 13 years | Brazil, Cross‐sectional, Cianorte Survey of School Children64,65 | P | |

| Mother's and father's education level when participant aged 10 years | Finland, Longitudinal Kuopio Ischaemic Heart Disease Risk Factor Study66,67,68,69,70 | R | |

| Mother's and father's education level when participant aged 4 years | 1946 British Birth Cohort71,72 | P | |

| Head of household's years of completed schooling when participant aged 15 years | USA National Longitudinal Survey of Older Men73 | R | |

| Participant household's highest education level | USA, Longitudinal Harvard Study of Moods and Cycles74 | P |

P, prospectively; R, retrospectively; SEP, socioeconomic position.

Table 3 Early‐life indicators of income.

| Indicator | Location, study design | Indicators of SEP measured | Criteria |

|---|---|---|---|

| Family income during childhood | Australia, longitudinal Mater—University of Queensland Study of Pregnancy and its Outcomes48,57 | P | Validity:Poor family financial situation is an important childhood characteristic in the explanation of socioeconomic inequalities in health56Relevance: May be affected by inflation over time, or changing criteria for definitions of povertyReliability:Potentially affected by recall bias and poor response rates Timeframe or age within indicator question may affect responses, as circumstances may change throughout early lifeDeconstruction:Economic distress construct could be broken down into component parts if necessary |

| USA, Woodlawn Cohort Study75 | P | ||

| Family income when participant aged 13 years | Brazil, Cross‐sectional, Cianorte Survey of School Children64,65 | P | |

| Household income when participant aged 18 years | USA, Wisconsin Longitudinal Study76 | P | |

| Economic distress construct in childhood based on receipt of public assistance or welfare, inability to pay for food, rent or mortgage, not having enough money to make ends meet, or borrowing money to pay for medical expenses | USA, Longitudinal Harvard Study of Moods and Cycles74 | R | |

| Degree to which family was considered wealthy | Finland, Longitudinal Kuopio Ischaemic Heart Disease Risk Factor Study68,69,70 | R | |

| Receipt of state welfare benefits | Australia, Longitudinal Mater—University of Queensland Study of Pregnancy and its Outcomes48,57 | P | |

| 1970 British Birth Cohort77 | P | ||

| Free school meals or on supplementary benefit | 1958 British Birth Cohort78 | P | |

| Household poverty status when participant born and aged 7 years | USA, Longitudinal National Collaborative Perinatal Project59,60 | P | |

| Period of 6 months during child hood when family was on welfare | USA, Cross‐sectional National Survey of Midlife Development54 | R | |

| Number of times household income was at least 200% below poverty line | USA, Longitudinal Alameda County Study39 | R | |

| Financial circumstances during childhood | The UK, Longitudinal Whitehall Study35 | R | |

| The Netherlands, Longitudinal Study of Socio‐Economic Health Differences58 | R | ||

| Sweden, Longitudinal level of living surveys79 | R |

*P, prospectively; R, retrospectively; SEP, socioeconomic position.

Table 4 Early‐life indicators of occupation.

| Indicator | Location, study design | Indicators of SEP measured | Criteria |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal grandfather's occupation | Australia, Longitudinal Mater—University of Queensland Study of Pregnancy and its Outcomes80 | P | Validity: Father's occupation is a valid marker of socioeconomic and environmental circumstances in childhood.81,82,83Information about past occupation could be as important as current occupation given that some occupations are less healthy than others87Relevance: Culturally and historically specific, cohort and period effects likely to exist.51 Cannot readily be used for groups outside the recognised labour force10Reliability:Potentially affected by recall bias Father's occupation was recalled accurately, reliably and by most respondents Changing coding criteria need to be taken into account for consistent measurement over timeDeconstruction: Not applicable |

| Maternal and paternal grandfather's occupation | Danish 1958 cohort of men51 | P | |

| Father's occupation | Australia, Longitudinal Mater—University of Queensland Study of Pregnancy and its Outcomes80 | P | |

| Britain, Longitudinal Whitehall Study35 | R | ||

| Danish 1958 cohort of men51 | P | ||

| Finland, Helsinki University Central Hospital Cohort84 | P | ||

| Finland Valmet cohort85 | R | ||

| The Netherlands, Longitudinal Study of Socio‐Economic Health Differences58 | R | ||

| Scotland, Glasgow Alumni Cohort86 | R | ||

| Longitudinal West of Scotland Collaborative Study33,37,88,89,90,91,92,93 | R | ||

| Spain, Cross‐sectional study94 | R | ||

| Sweden, Cross‐sectional Malmö Diet and Cancer Study82 | R | ||

| Sweden, Cross‐sectional Stockholm Heart Epidemiology Programme28 | R | ||

| USA, Longitudinal Alameda County Study53 | R | ||

| USA, Longitudinal Nurses' Health Study95 | P | ||

| USA, Cross‐sectional National Survey of Midlife Development54 | R | ||

| USA, Longitudinal Normative Aging Study55 | R | ||

| Father's longest held occupation | British Women's Heart and Health Study, cross‐sectional38,50,96,97,98,99 | R | |

| British Regional Heart Study, longitudinal100 | R | ||

| Father's occupation when participant born | Britain Newcastle Thousand Families Cohort Study101,102,103 | P | |

| Father's occupation when participant born and aged 7, 11 and 16 years | 1958 British Birth Cohort52,77,104,105,106 | P | |

| Father's occupation when participant born and aged 3 and 6 years | New Zealand, Longitudinal Christchurch Health and Development Study107 | P | |

| Father's occupation when participant born | New Zealand, Longitudinal Dunedin Multidisciplinary Health and Development Study108,109 | P | |

| Father's occupation when participant aged 4 years | 1946 British Birth Cohort71,72,110,111,112 | P | |

| Father's occupation when participant aged 14 years | British Household Panel Survey, cross‐sectional113 | R | |

| Father's occupation when participant aged 16 years | USA, Longitudinal Nurses' Health Study95 | R | |

| Mother's occupation | USA, Cross‐sectional National Survey of Midlife Development54 | R | |

| Parents' occupation at age 15 years | Slovakia, Cross‐sectional Survey of Adolescents61 | P | |

| Parents' occupation when participant aged 5, 10 and 16 years | 1970 British Birth Cohort77 | P | |

| Occupation of parents when participant born and aged 3, 5, 7, 9, 13, 15 and 26 years | New Zealand, Longitudinal Dunedin Multidisciplinary Health and Development Study114 | P | |

| Parents' occupation when participant aged 10 years | Finland, Longitudinal Kuopio Ischaemic Heart Disease Risk Factor Study66,68,69,70,115 | R | |

| Parents' occupation when participant born and aged 7 years | USA, Longitudinal National Collaborative Perinatal Project59,60 | P | |

| Head of household's occupation when participant born | Sweden, Uppsala Birth Cohort Study116 | P | |

| Head of household's occupation when participant aged 5 and 10 years | Britain Newcastle Thousand Families Cohort Study101,102,103 | P | |

| Head of household's occupation when participant aged 15 years | USA National Longitudinal Survey of Older Men73 | R | |

| Head of household's occupation when participant aged 10–14 years | Finland, Longitudinal Census Data Study40,117 | R | |

| Whether mother worked outside the home | USA, National Longitudinal Survey of Older Men73 | R | |

| Father or mother unemployed when they wanted to be working | Britain, Longitudinal Whitehall Study35 | R | |

| Participant's occupation at labour force entry | Sweden, Cross‐sectional Stockholm Female Coronary Risk Study118 | R | |

| Participant's first occupation | West of Scotland, Longitudinal Collaborative Study37,90,91,93 | R |

P, prospectively; R, retrospectively; SEP, socioeconomic position.

Table 5 Early‐life indicators of living conditions.

| Indicator | Location, study design | Indicators of SEP measured | Criteria |

|---|---|---|---|

| Whether family lived on a farm, and size of farm, at age 10 years | Finland, Longitudinal Kuopio Ischaemic Heart Disease Risk Factor Study68,69,70 | R | Validity:Overcrowding reflects childhood circumstances that may be directly or indirectly connected to health117Living in council housing has been shown to have a stronger association with midlife psychological distress among women than father's occupation and overcrowding112Relevance:These indicators are culturally, geographically and historically specific British data showed a secular change in material resources over time A 1970 cohort was more likely than a 1958 cohort to own their own home, and less likely to be overcrowded or share amenities119Reliability:More likely to be recalled accurately than categories such as parents' education or occupation Life grid methods using a temporal reference system have been shown to improve recall120Lifegrid method may improve reliability of recalled informationDeconstructionComposite or summary indicators may provide less information about the causal nature of associations between SEP and health |

| Number of rooms and number of people in the home | Finland, Helsinki University Central Hospital Cohort84 | P | |

| Overcrowding (ratio of people to number of rooms in household) | 1970 British Birth Cohort77 | P | |

| Overcrowding when participant aged 4 years | 1946 British Birth Cohort71,112 | P | |

| Overcrowding when participant aged 11 and 16 years | 1958 British Birth Cohort78 | P | |

| Overcrowding when participant born and aged 13 years | Brazil, Cross‐sectional Cianorte Survey of School Children64,65 | P | |

| Household amenities (sole use of bathroom, toilet, hot water) | 1970 British Birth Cohort77 | P | |

| Lack of hot water in house when participant aged 11 and 16 years | 1958 British Birth Cohort78 | P | |

| Presence of toilet inside house when participant born and aged 13 years | Brazil, Cross‐sectional Cianorte Survey of School Children64,65 | P/R | |

| Presence of toilet inside house before age 16 years | Britain, Longitudinal Whitehall Study35 | R | |

| Car ownership of family when participant born and aged 13 years | Brazil, Cross‐sectional Cianorte Survey of School Children64,65 | P/R | |

| Car ownership of family before age 16 years | Britain, Longitudinal Whitehall Study35 | R | |

| Family access to a car during childhood | British Women's Heart and Health Study, cross‐sectional98,99 | R | |

| Housing tenure | 1970 British Birth Cohort77 | P | |

| Housing tenure when participant aged 4 years | 1946 British Birth Cohort71,112 | P | |

| Housing tenure when participant born and aged 13 years | Brazil, Cross‐sectional Cianorte Survey of School Children64,65 | P/R | |

| Availability of piped water to house when participant born and aged 13 years | Brazil, Cross‐sectional Cianorte Survey of School Children64,65 | P/R | |

| Type of material used to build house when participant born and aged 13 years | Brazil, Cross‐sectional Cianorte Survey of School Children64,65 | P/R | |

| Childhood household amenities (living in a house with a bathroom, living in a house with a hot water supply, sharing a bedroom) | British Women's Heart and Health Study, cross‐sectional98,99 | R | |

| Housing conditions at birth and ages 5 and 10 years based on overcrowding, lack of hot water, shared toilet, and dampness or poor repair of house | Britain Newcastle Thousand Families Cohort Study102,103 | P | |

| Material home conditions at age 4 years was an aggregate variable based on state of repair of house, age of house, crowding, cleanliness of house, cleanliness of participant, and condition of participant's shoes and clothes | 1946 British Birth Cohort71,72 | P | |

| Life‐grid method to collect retrospective personal, residential and occupational histories. Lifetime exposures to a range of generally accepted health hazards, including atmospheric pollution, residential damp, occupational fumes and dusts, physically arduous work, lack of autonomy, cigarette smoking and inadequate nutrition during childhood and adulthood were estimated from details of household, residential, occupational and smoking histories. | Britain Boyd Orr Cohort121,122,123,124 | R | |

| Family amenity score in childhood up to age 10 years (presence of hot water tap and bathroom in family home, whether they shared a bedroom, car ownership) | British Regional Heart Study, longitudinal100 | R | |

| Material standard of living at age 15 years (owner occupied accommodation, owned car, owned summer cottage or second house in the countryside) | Danish 1958 cohort of men51 | P | |

| Housing conditions at age 0–19 years (Type of dwelling, status of home ownership, number of persons per room, telephone in dwelling, toilet or bath inside dwelling) | Norway Census data cohort125 | P | |

| Characteristics of place of residence in 1939 including whether area was depressed, population density, percentage of population in manual work, proportion of population in overcrowded housing, unemployment rate in area | Britain Office for National Statistics Longitudinal Study for England and Wales126 | P |

P, prospectively; R, retrospectively; SEP, socioeconomic position.

Table 6 Early‐life indicators of family structure.

| Indicator | Location, study design | Indicator of SEP measured | Criteria |

|---|---|---|---|

| Family structure at age 15 years | USA, National Longitudinal Survey of Older Men73 | R | Validity:Family structure, used to distinguish families with two parents from single‐parent families, and living conditions in the parental home, such as number of siblings and crowding, may influence adult SEP, and thus health in adulthood117Relevance:Historical context and cohort effects need to be taken into account Reliability:More likely to be recalled accurately than categories such as parents' education or occupation Time frame or age within indicator question may affect responses as circumstances may change throughout early lifeDeconstruction:Not applicable |

| Family size | 1946 British Birth Cohort112 | P | |

| 1958 British Birth Cohort78 | P | ||

| Sweden, Level of Living Surveys, longitudinal79 | R | ||

| Sweden, Cross‐sectional Stockholm Female Coronary Risk Study118 | R | ||

| USA, Woodlawn Cohort Study75 | P | ||

| Number of younger siblings | USA, longitudinal National Survey of Children63 | P | |

| Marital status of parents | USA, Longitudinal National Survey of Children63 | P | |

| Mother's marital status at participant's birth | Sweden, Uppsala Birth Cohort Study116 | P | |

| Ever in lone‐parent family before participant aged 16 years | British Household Panel Survey, cross‐sectional113 | R | |

| Single parent family when participant aged 11 and 16 years | 1958 British Birth Cohort78 | P | |

| Lived with both biological parents (or not) until age 16 years | USA, Cross‐sectional National Survey of Midlife Development54 | R | |

| Parental divorce or separation during childhood | Sweden, Level of Living Surveys, longitudinal79 | R | |

| Parental divorce or separation before participant aged 26 years | 1946 British Birth Cohort112 | P | |

| Parental divorce or death before participant aged 16 years | 1958 British Birth Cohort113,127 | P | |

| Birth order | Brazil, Cross‐sectional Cianorte survey of school children64,65 | R | |

| 1946 British Birth Cohort72,112 | P | ||

| Sweden, Cross‐sectional Stockholm Female Coronary Risk Study118 | R | ||

| Sweden, Uppsala Birth Cohort Study116 | P |

P, prospectively; R, retrospectively; SEP, socioeconomic position.

Table 7 Early‐life indicators of residential mobility.

| Indicator | Location, study design | Indicator of SEP measured | Criteria |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exposure to urban environment during first 5 years of life | Cameroon, Essential Non‐communicable Diseases Health Intervention Project, cross‐sectional128 | R | Validity:The number of moves may not be an adequate representation of the context in which moving occurred or the resources available at different geographic locations60Relevance:Culturally and historically specificReliability:More likely to be recalled accurately than categories such as parents' education or occupation Time frame or age within indicator question may affect responses as circumstances may change throughout early lifeDeconstruction:Not applicable |

| Lifestage timing of migration | Hong Kong, Cardiovascular Risk Factor Prevalence Study, cross‐sectional129 | R | |

| Number of residential moves since birth when participant aged 7 years | USA, Longitudinal National Collaborative Perinatal Project60 | P | |

| Number of times address changed | USA, Longitudinal National Survey of Children63 | P | |

| USA, Woodlawn Cohort Study75 | P | ||

| Number of years at current address | USA, Longitudinal National Survey of Children63 | P |

P, prospectively; R, retrospectively; SEP, socioeconomic position.

Validity

Choosing appropriate measures of SEP should depend on how SEP is considered to be associated with health. A Marxist or Weberian influence may be reflected in the choice of social class structure or life chance indicators such as education, occupation or income.14,15,130 Neomaterialist explanations for inequalities focus on the lack of material resources, whereas relative position on the social or occupational ladder is more important in psychosocial explanations.27,131

The association between the education level of respondents and that of their parents can be explained in different ways. Parents with higher education levels are likely to have a higher SEP, with better jobs, housing, neighbourhood and working conditions,15 higher incomes, and able to finance higher levels of education for their children. Psychologically, parents with higher education levels are more likely to instil strong educational values and norms in their children. Biologically, intellectual ability and thus educational attainment may be, at least partly, inherited.132 The influence of mother's and father's education has been shown to be different for men and women, supporting the need to include the education levels of both parents in descriptions of early‐life SEP.132

Income relates most closely to the material resources component of SEP. It is inversely correlated with suboptimal environmental conditions such as air quality, housing facilities and overcrowding, and school, work and neighbourhood environments.3 Occupation and employment conditions, reflecting both the physical and psychosocial environments in which people work, are the major link between education and income.15 Father's occupation is associated with adult height81,82 and early‐life material circumstances.100

In terms of family structure, single‐parent backgrounds have been associated with lower incomes and education levels.40 Family structure questions may also be important to determine whether the respondent lived with their biological parents, step‐parents or in some other arrangement. Obtaining information about education and occupation of parents may be irrelevant if respondents did not live with their parents during their early life. Number of siblings or birth order may also reflect childhood SEP, as human and material resources are likely to diminish as the family grows larger.116 Residential mobility has been negatively correlated with home ownership, which in turn is associated with housing quality and income.3

Living conditions, such as car ownership, housing tenure, crowding or amenities, and indicators of family structure and residential mobility are suggested to be merely proxy measures and should not be used when information on education, income and occupation is available.11,43 Although they are strongly correlated with SEP, they may be associated with health outcomes via causal pathways that are not related to SEP. For example, growing up in a single‐parent family may be related to poor health outcomes for socioeconomic reasons associated with low income, or it may be related to poorer health for psychological reasons resulting from the family breakdown.44

The use of various life‐course models (table 1) is evident in the specific indicator chosen to measure early‐life SEP. A focus on the critical period model is reflected in the measurement of SEP at the time of birth of participants.48,116 Use of the pathways model was shown through the measurement of SEP at a particular age during childhood or adolescence—for example, education of parents, father's occupation and housing conditions when participant was aged 4 years.71 Measurement of SEP—for example, father's occupation—at several ages37,52,114 supports a cumulative life‐course model, recognising that information on past occuoation of parents and respondents may be as important as current occupation.61 Existing data sets were sometimes also used opportunistically to examine life‐course hypotheses. In these cases, the selection of specific ages for measuring SEP was less likely to be guided by any particular life‐course model.

Validity, in terms of expected associations with health outcomes,46 has been shown for many indicators of early‐life SEP, with lower levels of SEP generally associated with adverse health outcomes. Parental education has been associated with psychosocial and cognitive functioning,66,115 dental health,64 pulmonary function,62 self‐reported general health,58 cardiovascular mortality53 and risky behaviours during adolescence.61 Financial situation during childhood has been associated with self‐reported general health in adulthood.58 Conditions of overcrowding and type of housing material at birth have been associated with poor dental health during adolescence.64 Occupational class of the parents, most commonly of the father, has been associated with cardiovascular risk factors,88,94,96 risky behaviours during adolescence,61 self‐reported limiting longstanding illness,101 self‐reported general health,58,104 psychosocial functioning,115 depression,59 persistent smoking,52 obesity,102,110 insulin resistance38,97 and diabetes,84 and overall,71 cardiovascular,33,37,53 stomach cancer and respiratory mortality.89 Growing up in a single‐parent household has been associated with behavioural, emotional and physical health problems.133 Residential instability in childhood has predicted an increased risk of lifetime major depression, although it is recognised that simply counting the number of geographical moves during childhood overlooks the context in which the transitions occurred and the resources available at those times.60 Geographical relocation to a more advantaged area before the age of 25 years was associated with increased risk of developing diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidaemia and coronary heart disease.129 Lifetime exposure to an urban environment was associated with increased body mass index, blood glucose and blood pressure in a Cameroon population survey.128

Relevance

Not all indicators of early‐life SEP are relevant for all population groups, at all times and in all places. Occupational coding cannot always be used for groups outside the recognised labour force,10 such as those who are unemployed, students or retired. Using father's occupation alone, without mother's occupation, is less relevant in more recent times in many countries, because women are increasingly likely to be in the work force.111,134 In addition, associations between early‐life SEP and health outcomes in later life were not always found to be consistent for men and women. For example, parental occupation has been shown to be associated with self‐reported limiting longstanding illness at age 50 years101 and cardiovascular risk factors94 among men, but not among women.

Although education level of parents is a relatively stable indicator of SEP over the adult life course of people, social norms and meanings of education change over time, and within and between population groups and cultures6; hence, caution is required in the interpretation of this indicator in surveillance systems. For example, although completion of high school was not necessary for many trade and professional positions in the first half of the 20th century, it is now considered to be essential for almost any career or employment, at least in many of the developed countries. This has implications for comparing people in different age cohorts, as those with the same educational level are unlikely to have experienced similar occupational opportunities. The effects of inflation and changing criteria for definitions of poverty also need to be taken into account when comparing the relationship of absolute income during early life with health over time.

Indicators such as whether the family lived on a farm, type of material used to build the house and amenities in the household are also culturally, geographically and historically specific, depend on the level of economic development of the country and would not be universally appropriate measures of early‐life SEP. Home and car ownership, for example, have different socioeconomic meanings in different places and at different times. Car ownership was shown to be a stronger marker of advantage in childhood for older than younger cohorts in the UK.135 Although home ownership is traditionally considered to be an indicator of advantage, rates of home ownership that are low (eg, in Switzerland) or declining (eg, in New Zealand) are not necessarily indicative of poorer SEP.136 Family size and structure are also historically and culturally specific. In Sweden early last century, for example, the more advantaged groups had a higher proportion of families with many children, whereas today, larger families are more common among disadvantaged groups.116

Some indicators of early‐life SEP, such as overcrowding and family size, may seem more relevant for health outcomes of certain infectious diseases because they indicate levels of hygiene and ease of transmission of infections.29 Such indicators may still be relevant in chronic disease surveillance systems as indirect measures of social disadvantage that are associated with increased risk of chronic conditions.

Reliability

Previous studies have shown high response rates with retrospective data on childhood social class based on father's occupational class obtained for 86% of all women in a British cohort,97 92% in the Alameda County Study,53 95% of men in the British Regional Heart Study,100 96% in the Kuopio Ischaemic Heart Disease Risk Factor Study115 and 98% of the Boyd Orr cohort.121 Parental education has also been shown to be well recalled, missing for only 6% of respondents in the study62 and 5% in the Kuopio Ischaemic Heart Disease Risk Factor Study.115 Studies have also found recalled information to be accurate, with 83% exact agreement or agreement within 1 unit of difference between recalled and historical records of father's occupation,120 and 81% agreement in recall of father's occupation between twin pairs.137 Several publications were not explicit about the proportion of respondents with missing data for early‐life SEP indicators.28,63,73,80,94 Others stated that respondents with missing data on early life were excluded from analyses.35,64,65,82,94,138 Respondents with missing data for father's occupation were sometimes classified according to their father's education level instead.53 Missing data on early‐life SEP are not necessarily a problem, unless those with missing data differ systematically from those with complete data. Women with data on both adult and child social class in the British Women's Heart and Health Study were younger, less likely to be current smokers and had smaller waist:hip ratios than those who had missing data.38 In the Whitehall Study, missing data were overall more common among those from the lowest employment grade.35

Using education of parents as an indicator of childhood SEP is advantageous because their education is less likely to change than occupation or income after young adulthood.1 This may be less true, however, for younger cohorts, and for women, who may return to study after child bearing. This has implications for the use of different ages when asking questions on early‐life SEP. For example, retrospectively asking adult respondents about their mother's education level when they were born, compared with when they were aged 4, 7 or 13 years, may yield different results.

A life‐grid method was shown to improve retrospective recall of early‐life information. This method includes cross‐referencing any changes in SEP with important dates in the respondent's life, such as marriages, births and deaths, and also with important external events such as wars or coronations.122

Deconstruction

Summary measures of early‐life SEP, such as the economic distress construct74 or childhood household amenities,50,98 can be broken down into their component parts. Although it is important to consider using multiple indicators of SEP, used in their aggregate form, it is difficult to distinguish exactly which components are associated with the health outcome,46 which is not helpful for informing specific policy and interventions. Summary indicators may consist of several components but may not incorporate all dimensions of SEP. The economic distress construct, for example, covers income‐related disadvantage but does not include any measures related to occupation or education. In addition, single indicators have greater ability than composite indicators in identifying the magnitude of, and trends in, mortality differentials.139

Conclusion

As surveillance is designed to monitor the prevalence of many different health outcomes among populations of different age and cultural groups, it would be ideal to include as many indicators of early‐life SEP as possible. It is recommended that education, income and occupation indicators of early‐life SEP, which directly reflect the resource and status‐based constructs of SEP be included as priority. If time and space in surveillance questionnaires permit, more proxy indicators of SEP related to living conditions, family structure and residential mobility could also be included to provide further insight into the pathways between SEP and health over the life course.

Analysis of the relationships between SEP over the life course and health is difficult, because complex socioeconomic factors are reduced to measurable indicators that may only ever produce an approximation of these relationships. As their name suggests, indicators are only indicative of a construct that cannot be measured exactly.47 Examination of the theoretical background of the indicators shows that some indicators, such as education, occupation and income, measure the construct of SEP more directly than others, such as family structure and residential mobility. These proxy indicators, however, are correlated with SEP and are shown to be associated with health in later life, sometimes showing a stronger association than occupation.112

All of the indicators assessed in this review have been used in quantitative studies. There may be other indicators of early‐life SEP that could be elucidated from qualitative investigations to provide further insights into the meanings of SEP over the life course and its relationship with health. This review has also focused on individual‐level indicators. Apart from the characteristics of area of residence during childhood used in a British study,126 no area‐level indicators were used in the reviewed studies to measure early‐life SEP. Although area‐level measures of socioeconomic disadvantage—for example, proportion of people unemployed or families on a low income in a suburb—may provide contextual explanations for geographical inequalities in health, its measurement in surveillance systems could be problematic owing to the ecological fallacy whereby the area‐level SEP does not correspond to the SEP of a person.6,46

Data on SEP during childhood obtained in surveillance systems, either through face‐to‐face or telephone interviews, must rely on retrospective reports from participants. This relies on the memory of participants, with respondents perhaps reporting an inflated or deflated view of their early‐life SEP, or not being able to remember at all. Such misclassification may reduce the strength of associations. Early‐life socioeconomic circumstances are shown to be recalled with high accuracy and among most respondents. Several studies, however, did not provide details on the proportion of respondents who had missing data on early‐life SEP indicators. There may be as much evidence for poor recall of early‐life information as there is for successful recall, but it is not as widely published. Simply excluding respondents with missing data on early‐life from analyses may introduce bias if this group is different in terms of socioeconomic experience and health characteristics than the group that does not have missing data. A temporal reference system, or life grid,120 can improve recall, although this may be difficult to apply in surveillance systems that use computer‐assisted telephone interviewing and are limited by restrictions on interview length.

Choice of indicators of early‐life SEP for use in surveillance systems need to consider time (position in history) and space (geographical and sociocultural context),63 and also the life‐course theories and aetiological pathways relevant to the health outcomes being investigated. For example, measuring early‐life SEP at age 10 years may not be as appropriate as measurement at the time of birth in the critical period model. Application of the cumulative model will include measurement of SEP at several stages across the life course. Indicators of SEP are also likely to be differentially relevant to various health outcomes and different age, sex or ethnic population groups. The continuous data collection feature of surveillance is advantageous for monitoring changes in SEP in the population over time and among different population groups. In addition, as surveillance systems rely on retrospective recall, the indicators chosen will depend on how well they perform in terms of recall and response rates, which may vary between different settings and data collection methods. Whereas some indicators, such as education level of parents, may be valid because they are less likely to change after young adulthood than occupation or income, other indicators, such as occupation of parents or material circumstances during childhood, may be more easily and accurately recalled, and thus may be more appropriate for use in surveillance systems in particular settings, at certain times and for specific population groups.

What this paper adds

This paper adds a comprehensive review of early‐life socioeconomic position (SEP) indicators that could be considered for use in population health surveillance systems. The review assesses indicators used in previous studies according to validity, relevance, reliability and deconstruction criteria, and suggests that indicators of early‐life SEP need to be relevant to the historical, geographical and sociocultural context in which the surveillance system is operating, and able to be measured retrospectively.

Policy implications

Potential to monitor the health effects of economic, social and educational policies over the long term exist if indicators of socioeconomic position over the life course are included in population health surveillance systems.

Using a life‐course approach in surveillance brings into focus the notion that economic, social and educational policies targeted at children and young people have health effects that are manifested far into the future.73 Surveillance systems have the potential to monitor these long‐term effects. Although information about causal pathways linking early‐life SEP, adult SEP and health in adulthood has come predominantly from longitudinal cohort studies, surveillance data can be combined with these insights as a basis for policy making and monitoring the effects of policies and interventions among different population groups, cohorts or generations. For example, comparisons in terms of health over the life course could be made between groups or cohorts who were and were not exposed to certain health, education and economic policies, such as provision of free milk or nutritious lunches at school, a system of free tertiary education or different taxation structures. Surveillance data collected consistently and continuously over the long term to monitor trends also act as a warning system about risk factors and chronic conditions emerging in different population groups. Taking into consideration the historical, geographical and sociocultural context when choosing indicators of early‐life SEP for use in surveillance systems will provide useful information on the socioeconomic life journey of people and how this is associated with the changing health of populations over time.

Abbreviations

SEP - socioeconomic position

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

References

- 1.Kaplan G, Keil J. Socioeconomic factors and cardiovascular disease: a review of the literature. Circulation 1993881973–1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Graham H, Kelley M.Health inequalities: concepts, frameworks and policy. London: Health Development Agency, 2004

- 3.Evans G, Kantrowitz E. Socioeconomic status and health: the potential role of environmental risk exposure. Annu Rev Public Health 200223303–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Turrell G, Mathers C. Socioeconomic status and health in Australia. Med J Aust 2000172434–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thacker S, Buffington J. Applied epidemiology for the 21st century. Int J Epidemiol 200131320–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berkman L, Macintyre S. The measurement of social class in health studies: old measures and new formulations. IARC Sci Publ 199713851–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davey Smith G. Socioeconomic differentials. In: Kuh D, Ben‐Shlomo Y, eds. A life course approach to chronic disease epidemiology. New York: Oxford University Press, 1997

- 8.Duncan G, Daly M, McDonough P.et al Optimal indicators of socioeconomic status for health research. Am J Public Health 2002921151–1157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grundy E, Holt G. The socioeconomic status of older adults: how should we measure it in studies of health inequalities? J Epidemiol Community Health 200155895–904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krieger N, Williams D, Moss N. Measuring social class in US public health research: concepts, methodologies, and guidelines. Annu Rev Public Health 199718341–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kunst A, Mackenbach J.Measuring socioeconomic inequalities in health. Copenhagen: World Health Organization, 1994

- 12.Lindelöw M.Sometimes more equal than others: how health inequalities depend on the choice of welfare indicator. Oxford: The World Bank Centre for Study of African Economies, Oxford University, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Macintyre S, McKay L, Der G.et al Socio‐economic position and health: what you observe depends on how you measure it. J Public Health Med 200325288–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oakes J, Rossi P. The measurement of SES in health research: current practice and steps toward a new approach. Soc Sci Med 200356769–784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lynch J, Kaplan G. Socioeconomic position. In: Berkman L, Kawachi I, eds. Social epidemiology. New York: Oxford University Press, 2000

- 16.Thacker S, Stroup D. Future directions for comprehensive public health surveillance and health information systems in the United States. Am J Epidemiol 1994140383–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Campostrini S. Surveillance systems and data analysis: continuously collected behavioural data. In: McQueen D, Puska P, eds. Global behavioral risk factor surveillance. New York: Kluwer Academic, 2003

- 18.Braveman P. Monitoring equity in health and healthcare: a conceptual framework. J Health Popul Nutr 200321181–192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tennant S, Szuster F.Nationwide monitoring and surveillance question development: diabetes mellitus. Adelaide: Public Health Information Development Unit, 2003

- 20.Teutsch S, Churchill R.Principles and practice of public health surveillance. 2nd edn. New York: Oxford University Press, 2000

- 21.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, Commonwealth Department of Health and Aged Care Workshop on health inequalities in Australia: data collection, information development and monitoring. Canberra: AIHW, 2000

- 22.Turrell G, Oldenburg B, McGuffog I.et alSocioeconomic determinants of health: towards a national research program and a policy and intervention agenda. Canberra: Queensland University of Technology, School of Public Health, Ausinfo, 1999

- 23.Susser E. Eco‐epidemiology: thinking outside the black box. Epidemiology 200415519–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Greenland S, Gago‐Dominguez M, Castelao J. The value of risk‐factor (“black‐box”) epidemiology. Epidemiology 200415529–535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Krieger N. Refiguring “race”: epidemiology, racialized biology and biological expressions of race relations. Int J Health Serv 200030211–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ben‐Shlomo Y, Kuh D. A life course approach to chronic disease epidemiology: conceptual models, empirical challenges and interdisciplinary perspectives. Int J Epidemiol 200231285–293. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kawachi I, Subramanian S, Almeida‐Filho N. A glossary for health inequalities. J Epidemiol Community Health 200256647–652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hallqvist J, Lynch J, Bartley M.et al Can we disentangle life course processes of accumulation, critical period and social mobility? An analysis of disadvantaged socio‐economic positions and myocardial infarction in the Stockholm Heart Epidemiology Program. Soc Sci Med 2004581555–1562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Galobardes B, Lynch J W, Davey Smith G. Childhood socioeconomic circumstances and cause‐specific mortality in adulthood: systematic review and interpretation. Epidemiol Rev 2004267–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Barker D.Fetal and infant origins of adult disease. London: BMJ, 1992

- 31.Barker D J, Gluckman P D, Godfrey K M.et al Fetal nutrition and cardiovascular disease in adult life. Lancet 1993341938–941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bartley M, Sacker A, Schoon I. Social and economic trajectories and women's health. In: Kuh D, Hardy R, eds. A life course approach to women's health. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002

- 33.Davey Smith G, Hart C. Life‐course socioeconomic and behavioral influences on cardiovascular disease mortality: the Collaborative Study. Am J Public Health 2002921295–1298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Graham H. Building an inter‐disciplinary science of health inequalities: the example of lifecourse research. Soc Sci Med 2002552005–2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Singh‐Manoux A, Ferrie J E, Chandola T.et al Socioeconomic trajectories across the life course and health outcomes in midlife: evidence for the accumulation hypothesis? Int J Epidemiol 2004331072–1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ciocco A, Klein H, Palmer C. Child health and the selective service physical standards. Public Health Rep 1941562365–2375. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Davey Smith G, Hart C, Blane D.et al Lifetime socioeconomic position and mortality: prospective observational study. BMJ 1997314547–552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lawlor D, Ebrahim S, Davey Smith G. Socioeconomic position in childhood and adulthood and insulin resistance: cross sectional survey using data from British Women's Heart and Health Study. BMJ 2002325805–809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lynch J, Kaplan G, Shema S. Cumulative impact of sustained economic hardship on physical, cognitive, psychological, and social functioning. N Engl J Med 19973371889–1895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pensola T, Martikainen P. Cumulative social class and mortality from various causes of adult men. J Epidemiol Community Health 200357745–751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kuh D, Ben‐Shlomo Y, eds. Introduction: a life course approach to the aetiology of adult chronic disease. A life course approach to chronic disease epidemiology. New York: Oxford University Press, 1997

- 42.Davey Smith G, Lynch J. Life course approaches to socioeconomic differentials in health. In: Kuh D, Ben‐Shlomo Y, eds. A life course approach to chronic disease epidemiology. 2nd edn. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004

- 43.Galobardes B, Shaw M, Lawlor D A.et al Indicators of socioeconomic position (part 1). J Epidemiol Community Health 2006607–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Galobardes B, Shaw M, Lawlor D A.et al Indicators of socioeconomic position (part 2). J Epidemiol Community Health 20066095–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Krieger N. A glossary for social epidemiology. J Epidemiol Community Health 200155693–700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liberatos P, Link B G, Kelsey J L. The measurement of social class in epidemiology. Epidemiol Rev 19881087–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Flowers J, Hall P, Pencheon D. Public health indicators. Public Health 2005119239–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Najman J, Bor W, Morrison J.et al Child developmental delay and socio‐economic disadvantage in Australia: a longitudinal study. Soc Sci Med 199234829–835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Goodman E, McEwen B S, Huang B.et al Social inequalities in biomarkers of cardiovascular risk in adolescence. Psychosom Med 2005679–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lawlor D A, Morton S M, Nitsch D.et al Association between childhood and adulthood socioeconomic position and pregnancy induced hypertension: results from the Aberdeen children of the 1950s cohort study. J Epidemiol Community Health 20055949–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Osler M, Andersen A M, Batty G D.et al Relation between early life socioeconomic position and all cause mortality in two generations. A longitudinal study of Danish men born in 1953 and their parents. J Epidemiol Community Health 20055938–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jefferis B J, Power C, Graham H.et al Effects of childhood socioeconomic circumstances on persistent smoking. Am J Public Health 200494279–285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Beebe‐Dimmer J, Lynch J W, Turrell G.et al Childhood and adult socioeconomic conditions and 31‐year mortality risk in women. Am J Epidemiol 2004159481–490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Combs Y. Midlife health of African‐American women: cumulative disadvantage as a predictor of early senscence. Res Sociol Health Care 200220123–135. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cupertino A. The impact of life course socioeconomic status on cardiovascular disease and overall mortality. Diss Abstr Int 2001621614 [Google Scholar]

- 56.van Lenthe F J, Schrijvers C T, Droomers M.et al Investigating explanations of socio‐economic inequalities in health: the Dutch GLOBE study. Eur J Public Health 20041463–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bor W, Najman J, Andersen M.et al Socioeconomic disadvantage and child morbidity: an Australian longitudinal study. Soc Sci Med 1993361053–1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.van de Mheen H, Stronks K, Mackenbach J. A lifecourse perspective on socio‐economic inequalities in health: the influence of childhood socio‐economic conditions and selection processes. In: Bartley M, Blane D, Davey Smith G, eds. The sociology of health inequalities. Oxford: Blackwell, 1998

- 59.Gilman S, Kawachi I, Fitzmaurice G.et al Socioeconomic status in childhood and the lifetime risk of major depression. Int J Epidemiol 200231359–367. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gilman S E, Kawachi I, Fitzmaurice G M.et al Socio‐economic status, family disruption and residential stability in childhood: relation to onset, recurrence and remission of major depression. Psychol Med 2003331341–1355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Geckova A, van Dijk J, Groothoff J.et al Socio‐economic differences in health risk behaviour among Slovak adolescents. Soz Praventivmed 200247233–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jackson B, Kubzansky L, Cohen S.et al A matter of life and breath: childhood socioeconomic status is related to young adult pulmonary function in the CARDIA study. Int J Epidemiol 200433271–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wheaton B, Clarke P. Space meets time: integrating temporal and contextual influences on mental health in early adulthood. Am Sociol Rev 200368680–706. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nicolau B, Marcenes W, Hardy R.et al A life‐course approach to assess the relationship between social and psychological circumstances and gingival status in adolescents. J Clin Periodontol 2003301038–1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Nicolau B, Marcenes W, Bartley M.et al A life course approach to assessing causes of dental caries experience: the relationship between biological, behavioural, socio‐economic and psychological conditions and caries in adolescents. Caries Res 200337319–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Turrell G, Lynch J, Kaplan G.et al Socioeconomic position across the lifecourse and cognitive function in late middle age. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 200257BS43–S51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gilman S, Abrams D, Buka S. Socioeconomic status over the life course and stages of cigarette use: initiation, regular use, and cessation. J Epidemiol Community Health 200357802–808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lynch J W, Everson S A, Kaplan G A.et al Does low socioeconomic status potentiate the effects of heightened cardiovascular responses to stress on the progression of carotid atherosclerosis? Am J Public Health 199888389–394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lynch J, Kaplan G, Cohen R.et al Childhood and adult socioeconomic status as predictors of mortality in Finland. Lancet 1994343524–527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lynch J, Kaplan G, Salonen J. Why do poor people behave poorly? Variation in adult health behaviours and psychosocial characteristics by stages of the socioeconomic lifecourse. Soc Sci Med 199744809–819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kuh D, Hardy R, Langenberg C.et al Mortality in adults aged 26–54 years related to socioeconomic conditions in childhood and adulthood: post war birth cohort study. BMJ 20023251076–1080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Richards M, Wadsworth M E. Long term effects of early adversity on cognitive function. Arch Dis Child 200489922–927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hayward M D, Gorman B K. The long arm of childhood: the influence of early‐life social conditions on men's mortality. Demography 20044187–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wise L, Krieger N, Zierler S.et al Lifetime socioeconomic position in relation to onset of perimenopause. J Epidemiol Community Health 200256851–860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ensminger M E, Juon H S, Fothergill K E. Childhood and adolescent antecedents of substance use in adulthood. Addiction 200297833–844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Singer B, Ryff C D. Hierarchies of life histories and associated health risks. Ann N Y Acad Sci 199989696–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Schoon I, Sacker A, Bartley M. Socio‐economic adversity and psychosocial adjustment: a developmental‐contextual perspective. Soc Sci Med 2003571001–1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Power C, Li L, Manor O. A prospective study of limiting longstanding illness in early adulthood. Int J Epidemiol 200029131–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lundberg O. The impact of childhood living conditions on illness and mortality in adulthood. Soc Sci Med 1993361047–1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Najman J, Aird R, Bor W.et al The generational transmission of socioeconomic inequalities in child cognitive development and emotional health. Soc Sci Med 2004581147–1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Rona R J. Genetic and environmental factors in the control of growth in childhood. Br Med Bull 198137265–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Rosvall M, Ostergren P O, Hedblad B.et al Life‐course perspective on socioeconomic differences in carotid atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2002221704–1711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Kuh D, Ben‐Shlomo Y, eds. A life course approach to chronic disease epidemiology. New York: Oxford University Press, 1997

- 84.Eriksson J G, Forsen T J, Osmond C.et al Pathways of infant and childhood growth that lead to type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2003263006–3010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Brunner E J, Kivimaki M, Siegrist J.et al Is the effect of work stress on cardiovascular mortality confounded by socioeconomic factors in the Valmet study? J Epidemiol Community Health 2004581019–1020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Okasha M, McCarron P, McEwen J.et al Childhood social class and adulthood obesity: findings from the Glasgow Alumni Cohort. J Epidemiol Community Health 200357508–509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Fuchs V. Reflections on the socio‐economic correlates of health. J Health Econ 200423653–661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Blane D, Hart C, Davey Smith G.et al Association of cardiovascular disease risk factors with socioeconomic position during childhood and during adulthood. BMJ 19963131434–1438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Davey Smith G, Hart C, Blane D.et al Adverse socioeconomic conditions in childhood and cause specific adult mortality: prospective observational study. BMJ 19983161631–1635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Hart C L, Davey Smith G, Blane D. Inequalities in mortality by social class measured at 3 stages of the lifecourse. Am J Public Health 199888471–474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Heslop P, Davey Smith G, Macleod J.et al The socioeconomic position of employed women, risk factors and mortality. Soc Sci Med 200153477–485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Macleod J, Davey Smith G, Heslop P.et al Are the effects of psychosocial exposures attributable to confounding? Evidence from a prospective observational study on psychological stress and mortality. J Epidemiol Community Health 200155878–884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Hart C, Davey Smith G, Blane D. Social mobility and 21 year mortality in a cohort of Scottish men. Soc Sci Med 1998471121–1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Regidor E, Banegas J R, Gutierrez‐Fisac J L.et al Socioeconomic position in childhood and cardiovascular risk factors in older Spanish people. Int J Epidemiol 200433723–730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Rich‐Edwards J W, Colditz G A, Stampfer M J.et al Birthweight and the risk for type 2 diabetes mellitus in adult women. Ann Intern Med 1999130278–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Ebrahim S, Montaner D, Lawlor D A. Clustering of risk factors and social class in childhood and adulthood in British women's heart and health study: cross sectional analysis. BMJ 2004328861–865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Lawlor D, Davey Smith G, Ebrahim S. Life course influences on insulin resistance: findings from the British Women's Heart and Health Study. Diabetes Care 20032697–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Lawlor D A, Ebrahim S, Davey Smith G. The association of socio‐economic position across the life course and age at menopause: the British Women's Heart and Health Study. BJOG 20031101078–1087. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Lawlor D A, Davey Smith G, Ebrahim S. Association Bbetween childhood socioeconomic status and coronary heart disease risk among postmenopausal women: findings from the British Women's Heart and Health Study. Am J Public Health 2004941386–1392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Wannamethee S G, Whincup P H, Shaper G.et al Influence of fathers' social class on cardiovascular disease in middle‐aged men. Lancet 19963481259–1263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Adams J, White M, Pearce M.et al Life course measures of socioeconomic position and self reported health at age 50: prospective cohort study. J Epidemiol Community Health 2004581028–1029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Parker L, Lamont D, Unwin N.et al A lifecourse study of risk for hyperinsulinaemia, dyslipidaemia and obesity (the central metabolic syndrome) at age 49–51 years. Diabetes Med 200320406–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Lamont D, Parker L, White M.et al Risk of cardiovascular disease measured by carotid intima‐media thickness at age 49–51: lifecourse study. BMJ 2000320273–278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Hertzman C, Power C, Matthews S.et al Using an interactive framework of society and lifecourse to explain self‐rated health in early adulthood. Soc Sci Med 2001531575–1585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Parsons T J, Power C, Manor O. Fetal and early life growth and body mass index from birth to early adulthood in 1958 British cohort: longitudinal study. BMJ 20013231331–1335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Jefferis B J, Power C, Graham H.et al Changing social gradients in cigarette smoking and cessation over two decades of adult follow‐up in a British birth cohort. J Public Health (Oxford) 20042613–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Fergusson D, Swain‐Campbell N, Horwood J. How does childhood economic disadvantage lead to crime? J Child Psychol Psychiatry 200445956–966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Thomson W M, Poulton R, Milne B J.et al Socioeconomic inequalities in oral health in childhood and adulthood in a birth cohort. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 200432345–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Thomson W M, Poulton R, Kruger E.et al Socio‐economic and behavioural risk factors for tooth loss from age 18 to 26 among participants in the Dunedin Multidisciplinary Health and Development Study. Caries Res 200034361–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Langenberg C, Hardy R, Kuh D.et al Central and total obesity in middle aged men and women in relation to lifetime socioeconomic status: evidence from a national birth cohort. J Epidemiol Community Health 200357816–822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.McLaren L, Kuh D. Women's body dissatisfaction, social class, and social mobility. Soc Sci Med 2004581575–1584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Kuh D, Hardy R, Rodgers B.et al Lifetime risk factors for women's psychological distress in midlife. Soc Sci Med 2002551957–1973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Benzeval M, Dilnot A, Judge K.et al Income and health over the lifecourse: evidence and policy implications. In: Graham H, ed. Understanding health inequalities. Buckingham: Open University Press, 2000

- 114.Poulton R, Caspi A, Milne B.et al Association between children's experience of socioeconomic disadvantage and adult health: a life‐course study. Lancet 20023601640–1645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Harper S, Lynch J, Hsu W‐L.et al Life course socioeconomic conditions and adult psychosocial functioning. Int J Epidemiol 200231395–403. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Modin B. Birth order and mortality: a life‐long follow‐up of 14,200 boys and girls born in early 20th century Sweden. Soc Sci Med 2002541051–1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Pensola T, Martikainen P. Life‐course experiences and mortality by adult social class among young men. Soc Sci Med 2004582149–2170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Wamala S, Lynch J, Kaplan G. Women's exposure to early and later life socioeconomic disadvantage and coronary heart disease risk: the Stockholm Female Coronary Risk Study. Int J Epidemiol 200130275–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Schoon I, Bynner J, Joshi H.et al The influence of context, timing, and duration of risk experiences for the passage from childhood to midadulthood. Child Dev 2002731486–1504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Berney L R, Blane D B. Collecting retrospective data: accuracy of recall after 50 years judged against historical records. Soc Sci Med 1997451519–1525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Holland P, Berney L, Blane D.et al Life course accumulation of disadvantage: childhood health and hazard exposure during adulthood. Soc Sci Med 2000501285–1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Blane D, Berney L, Davey Smith G.et al Reconstructing the life course: health during early old age in a follow‐up study based on the Boyd Orr cohort. Public Health 1999113117–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Blane D, Higgs P, Hyde M.et al Life course influences on quality of life in early old age. Soc Sci Med 2004582171–2179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Blane D, Berney L, Montgomery S. Domestic labour, paid employment and women' health: analysis of life course data. Soc Sci Med 200152959–965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Naess O, Claussen B, Thelle D S.et al Cumulative deprivation and cause specific mortality. A census based study of life course influences over three decades. J Epidemiol Community Health 200458599–603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Curtis S, Southall H, Congdon P.et al Area effects on health variation over the life‐course: analysis of the longitudinal study sample in England using new data on area of residence in childhood. Soc Sci Med 20045857–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Hope S, Power C, Rodgers B. The relationship between parental separation in childhood and problem drinking in adulthood. Addiction 199893505–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Sobngwi E, Mbanya J C, Unwin N C.et al Exposure over the life course to an urban environment and its relation with obesity, diabetes, and hypertension in rural and urban Cameroon. Int J Epidemiol 200433769–776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Schooling M, Leung G M, Janus E D.et al Childhood migration and cardiovascular risk. Int J Epidemiol 2004331219–1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Susser I. Social theory and social class. IARC Scientific Publications 199713841–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Lynch J, Davey Smith G, Kaplan G.et al Income inequality and mortality: importance to health of individual income, psychosocial environment, or material conditions. BMJ 20003201200–1204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Baxter J. How much does parental education explain educational attainment of males and females in Australia? Negotiating the Life Course Discussion Paper Series. Australian National University; Canberra 2002

- 133.Harper C, Cardona M, Bright M.et alHealth determinants Queensland 2004: at a glance. Brisbane: Public Health Services and Health Information Centre, Queensland Health, 2004

- 134.Australian Bureau of Statistics Australian social trends 2005. Canberra: ABS, 2005

- 135.Ellaway A, Macintyre S, McKay L. The historical specificity of early life car ownership as an indicator of socioeconomic position. J Epidemiol Community Health 200357277–278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Oswald A.The housing market and Europe's unemployment: a non‐technical paper. Warwick, UK: Department of Economics, University of Warwick, 1999

- 137.Krieger N, Okamoto A, Selby J V. Adult female twins' recall of childhood social class and father's education: a validation study for public health research. Am J Epidemiol 1998147704–708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.van de Mheen H, Stronks K, Looman C.et al Does childhood socioeconomic status influence adult health through behavioural factors? Int J Epidemiol 199827431–437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Hayes L, Quine S, Taylor R.et al Socio‐economic mortality differentials in Sydney over a quarter of a century, 1970–94. Aust N Z J Public Health 200226311–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]