Abstract

Objective

To determine the weekly financial cost of a diet as recommended by national policy in two parents with two children, single parents with one child and single old people with low income, and begin to identify, in a rich country context, variation in food item availability, price and household purchasing capacity.

Design

Food baskets were developed based on national dietary recommendations and purchasing patterns of these household groups. National‐level prices of each food were identified, as well as pricing across a representative selection of Irish retail outlet types. Basket costs were assessed relative to the financial capacity of household type.

Results

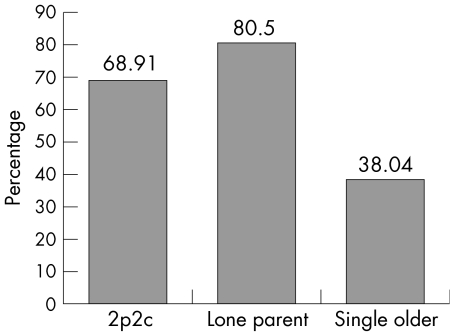

The types of retail outlets in which low‐income groups tend to shop do not carry many own brand items and is less likely to stock healthy options, but when they do, they are more expensive than in other outlets. Single parents with one child, two adults with two children and single older people would have to spend 80%, 69% and 38%, respectively, of their weekly household income to purchase the food basket based on economy‐line products.

Conclusions

Financial access to and availability of healthy food options must be considered through a national policy cognisant of basic human needs for healthy living. This research provides evidence on the direct costs of healthy eating for policy and planning to ensure not only financial capacity but also to guarantee that affordable healthy food choices are physically available to all groups in society.

As in other westernised countries, socially disadvantaged people and households have worse dietary‐related health outcomes1,2 and poorer dietary behaviour than richer members of Irish society3,4,5; documented evidence suggesting that certain groups indeed experience food poverty.6,7,8 Food poverty is a multidimensional experience, referring to the lack of a nutritionally adequate diet and the related effects on health, culture and social participation.9

Dietary choice is strongly affected by structural, material and psychosocial factors.9,10 It is generally accepted that in rich economies, the main structural barriers to healthy food choices are restricted access owing to financial and physical constraints, coupled with an excess availability of processed food.11 Studies have shown that among low‐income groups, price is the greatest motivating factor of food choice.12 The effect of food price on a person's behaviour had been observed in the US, where price reductions saw positive increases in the sales of low‐fat foods and fruits and vegetables.13 The type of retail outlet accessible to people determines the range of foodstuffs available and the prices paid.14 These factors run in parallel with the levels of disposable income and the amount of money a person or household allocates to food expenditure.

Determining the adequacy of income levels requires their evaluation against a benchmark. Such a benchmark is internationally known as a minimum income standard (MIS).15 One approach used in the development of MIS was estimation of budget standards. These are based on the prices for baskets of goods such as food, clothing, household services and leisure goods, which can represent the income required by households of different composition to reach defined living standards.16,17 Budget standards aim to capture both the normative and customary or behavioural dimensions of people's lifestyles and living conditions. The methods reflects this by adopting a sequenced approach, in which initial budgets developed by “expert” researchers are modified in light of actual expenditure patterns

Food budget standards were initiated in the UK at the start of the 20th century,18 revisited in the early 1990s,19 and more recently developed to estimate the realistic costs of a healthy diet for several population groups16,20,21 and, more generally, a healthy way of living.22,23 Irish food budget standards have not been developed to date. A recent study of food poverty in Ireland6 identified a lack of knowledge on the direct financial cost of purchasing a diet as recommended by national policy. The viability of compliance with the recommendations, on the basis of the financial capacity of low‐income households, was therefore unclear. This paper aims to provide such evidence with which future policies can be informed. The overall objective of this study is to assess the financial and structural contributors to healthy eating. The direct weekly financial cost of purchasing a healthy diet is assessed among three low‐income household types identified in national and international literature as being at risk of food poverty—that is, two parents with two children, lone parents with one child and old people living alone. In doing so, a food budget standard is set on the basis of reasonable and low‐cost prices. In addition, this study identifies issues of healthy food availability and accessibility, expressed in terms of food item availability and price variation by retail outlet type.

Methods

Food basket development

Development of the food basket is reported in detail elsewhere (http://www.cpa.ie/pub_workingpapers.htm) and follows methods developed internationally.17,21 Irish dietary recommendations are depicted graphically by a five‐shelf food pyramid. Each shelf of the pyramid recommends daily consumption of several servings of a particular food group, which on consumption are expected to provide the recommended balance of energy and nutrient intake.24 Although foodstuffs from the top shelf of the pyramid are high in fat and refined sugar and are not considered healthy, a cut‐off of less than three servings daily from this shelf is used generally as a practicable suggestion.3

Food baskets for each household type were compiled based on aggregated 7‐day menus, developed to ensure a balanced number of servings from the food pyramid shelves for each household member. However, it is important not to develop baskets that are unrepresentative and unacceptable to the concerned populations.21 For this reason, the existing 1999–2000 household budget survey data, which contain 146 food items purchased for home consumption,25 were used to identify habitual food‐purchasing patterns of the lowest‐income quintile of two parent–two children, single parent–one child and single older‐person households (total n = 1814), and this was used to inform the food basket's content.

The food baskets were constructed to contain items in purchasable quantities (eg, 1 litre of milk) and were based only on at‐home consumption. Menus were derived from a recipe book on Irish healthy eating on a low budget.26 The baskets do not include alcohol.

Retail cost of food baskets

The food baskets were costed at the national level using prices available through Tesco Ireland online database (www.tesco.ie). Both market brand and own brand prices were recorded. Each food basket was also priced across a representative selection of the four retail outlet types in Ireland. Multiples, which are the major supermarket multiples (eg, —Dunnes, Tesco); Groups/Symbols, which are independent supermarkets belonging to buying or “symbol” groups (eg, Supervalu); Foreign outlets, which are German discounters (eg, Aldi); and Independents (eg, corner shops). In the summer of 2003, two fieldworkers visited 13 of the 15 retail outlets approached in Galway city and physically documented the cost price, weight and retail price per unit weight for each food in the basket.27 Prices were noted for the leading market brand and the outlets' own brand. When own brand lines were not available, the market brand price was substituted. Where more than one brand of the same product was offered, the price of the cheaper brand was recorded. In those instances when a food item was not stocked, the multiple equivalent price was used. Where price per weight was not available, as in the case of some fruit, equivalent weights were estimated using a book of food portion sizes.28

Financial resources available to low‐income households

The total financial resource available to each household type was taken as income obtained solely through reliance on social‐welfare entitlements. Information on the 2003 social‐welfare entitlements of each household type was obtained from the Department of Social and Family Affairs29: two adults (both unemployed) with two dependent children, €241.20; single mother with one dependent child, €144.10; and people aged ⩾65 years living alone on old age contributory pension, €165.00. The cost of each food basket was expressed as a percentage of the household income available in the three household types.

Results

Direct financial cost of food baskets

At the national level, each household food basket is between 12% and 15% cheaper when low‐cost own brand options of the recommended food items are purchased compared with market brand baskets (table 1). Dairy products are almost half the price in two of the three household types if own brand items are chosen. Own brand products from the top shelf of the food pyramid are often much cheaper than the market brand equivalent.

Table 1 National‐level retail cost of recommended food basket for three household types.

| Food group | 2 Parents, 2 children | Lone parent, 1 child | Single older people | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MB (€) | OB (€) | % Diff | MB (€) | OB (€) | % Diff | MB (€) | OB (€) | % Diff | |

| Cereals, breads and potatoes | 28.45 | 24.79 | 13 | 19.47 | 14.55 | 25 | 12.02 | 7.85 | 35 |

| Fruit and vegetables | 29.61 | 26.63 | 10 | 19.72 | 20.46 | −4 | 20.99 | 20.74 | 1 |

| Dairy products | 20.16 | 12.84 | 36 | 10.16 | 5.52 | 46 | 3.04 | 2.81 | 8 |

| Meat, fish and alternatives | 44.91 | 42.49 | 5 | 34.90 | 33.02 | 5 | 19.22 | 17.55 | 9 |

| High sugar, High fat | 44.38 | 36.36 | 18 | 38.52 | 30.47 | 21 | 19.38 | 16.88 | 13 |

| Total | 167.51 | 143.11 | 15 | 122.77 | 104.02 | 15 | 74.65 | 65.83 | 12 |

MB, market brand; OB, own brand; % Diff, % difference between MB and OB, with MB as reference.

Basket price and availability by retail outlet type

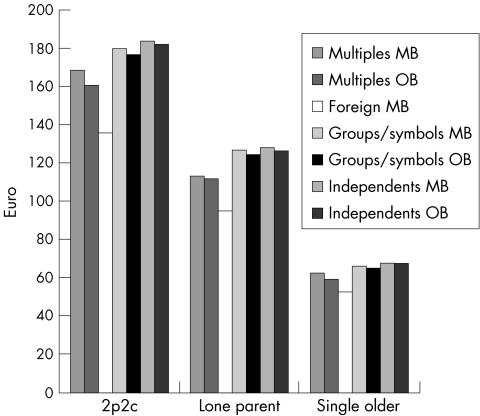

The basket costs from the 13 retail outlets are averaged under the corresponding retail category. The average cost of the two parents–two children food basket is €171.20 (market brands) and €167.60 (own brands). The own brand basket for this population group is the least expensive in the Foreign outlet (€129.65) and the most expensive outlet is the Group/Symbol where the basket costs €188 (fig 1). The average cost of the healthy food basket for a single mother with one child is €118.84 (market brands) and €116.94 when own brand options are included where available. The basket is cheapest in the Foreign retail category (€91.62) and most expensive from the Group/Symbol outlet type (€132.88). The basket designed for the older people living alone is the least expensive at €63.99 (market brands) and €62.65 (own brands). The least expensive retail outlet is again a Foreign outlet (€50.75) and the most expensive is the Independent retail category (€70.42).

Figure 1 Retail cost of market brand (MB) and own brand (OB) food basket by retail outlet type, for each household category. 2p2c, Two parents–two children household; lone parent, lone parent with one child; single older, older person living alone.

The Multiples visited stock most of the foods in the baskets. This was not the case in the Independents and Groups/Symbols, which frequently offer only a limited range of fruit and vegetables and little or no meat, fish and poultry. By contrast, almost every Independent stocks every foodstuff from the top shelf of the food pyramid in the basket.

Although not presented here, standardised prices per unit weight of all own brand and market brand items highlight that weight for weight, own brand items are generally cheaper than market brand equivalents. Own brand versions of sausages and tins of beans are substantially cheaper than major market brands, and most of the own brand lines of foods high in fat and sugar are cheaper than the market brand. However, there are two important points to note. Firstly, not all outlets stock own brand lines, and, where this was the case, the market brand equivalent price was entered into the basket costing. A wide range of own brand foods is available in the Multiples. The Foreign stores almost exclusively offer their own Foreign brand of foods and have few major market brand lines. A limited range of own brand lines is available in the Groups/Symbols or the Independents. Secondly, the own brand food prices are based on quantities that accord with foods available in the shops. Retailer own brand products vary in size and are often available only in larger sizes than their market brand equivalents. For example, fruit and vegetables are often available only in bags in the own brand lines, unlike the market brand fruit and vegetables that are usually available loose. When relatively small volumes of fruit and vegetables are required, the own brand items incur more expense than the market brand equivalent because of inappropriate availability that is larger than required.

Food pyramid recommendations and outlet price variation

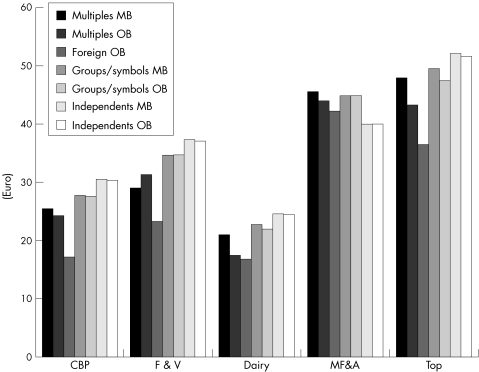

Foreign outlets are the most inexpensive place for a two parents–two children household to purchase foods recommended from all the categories except meat, fish and alternatives (fig 2). Independents are the most expensive outlet type to purchase high fat and high sugar foods (€51.69), fruit and vegetables (€36.94), dairy products (€24.35) and cereals, breads and potatoes (€30.27). Meat, fish and alternatives are the most expensive in the Groups/Symbols (€44.91) and the cheapest in the Independents (€40).

Figure 2 Cost of dietary recommendations for a two parents–two children household. CBP, cereals, breads and potatoes; Dairy, milk, cheese and yoghurt; F&V, fruit and vegetables; MB, market brand; MF&A, meat, fish and alternatives; OB, own brand; top, top shelf (foods high in fat and sugar).

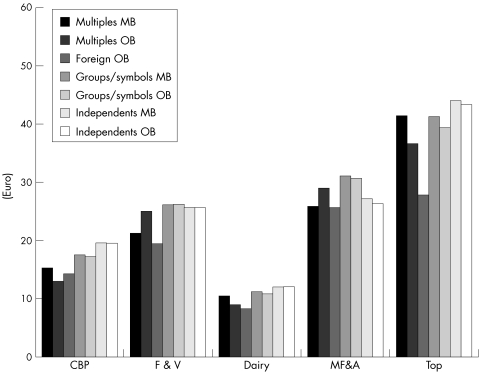

Multiples are the cheapest outlet for a lone parent–one child household to purchase foods from the cereal, bread and potatoes shelf (€12.95) compared with Independents who charge almost €20 (fig 3). The Foreign store is the cheapest place to purchase dairy items (€8.10), meat, fish and alternatives (€25.66), fruits and vegetables (€19.30), and foods from the top shelf (€27.62). Meat, fish and alternatives, and foods from the top shelf are the most expensive food categories across the different retail categories.

Figure 3 Cost of dietary recommendations for a lone parent–one child household. CBP, cereals, breads and potatoes; Dairy, milk, cheese and yoghurt; F&V, fruit and vegetables; MB, market brand; MF&A, meat, fish and alternatives; OB, own brand; top, top shelf (foods high in fat and sugar).

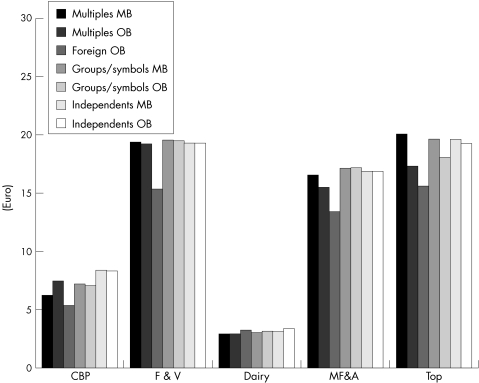

For single older households, the least expensive retail outlet type in which to purchase all food groups (except dairy products where the Multiple is the cheapest) is the Foreign retail category (fig 4). Independents are the most expensive shop in which to purchase cereals, breads and potatoes (€8.31), and dairy products (€3.08); the Groups/Symbols are the most expensive place to purchase meat, fish and alternatives (€17.09), and fruit and vegetables (€19.45); and the Multiples are the most expensive place to purchase foods from the top shelf (€20.03), although their own brand produce is almost as cheap as the Foreign outlet.

Figure 4 Cost of dietary recommendations for a single older person household. CBP, cereals, breads and potatoes; Dairy, milk, cheese and yoghurt; F&V, fruit and vegetables; MB, market brand; MF&A, meat, fish and alternatives; OB, own brand; top, top shelf (foods high in fat and sugar).

Financial capacity of low‐income households to purchase healthy food baskets

A household of two adults with two children, a single parent with one child and an older person living alone, dependent on social welfare benefits as their income, would have to spend 69%, 80% and 38%, respectively, of their weekly welfare entitlements to purchase the theoretical baskets of foodstuffs (fig 5). Although not reported here, a similar finding was observed when using a broader measure of financial capacity, that of average reported disposable income, estimated using the bottom quintile of income distribution in the 1999–2000 household budget survey adjusted to June 2003 levels.

Figure 5 Food basket cost as a proportion of weekly social‐welfare entitlements. 2p2c, two parents–two children household; lone parent, lone parent with one child; single older, old person living alone.

Discussion

This costing of food baskets, compliant with national dietary guidelines, highlights the current inequity in dietary choice in the Republic of Ireland and the underlying structural issues of financial access to and availability of healthy food among three population groups vulnerable to food poverty. An important caveat of these data is their sole relationship with home consumption and lack of recognition of the social practice of eating out.25

The type and distribution of retail outlets in Ireland has changed enormously over the past 40 years, mirroring the general trend across Europe in the closure of traditional small retailers, concentrating on bigger supermarkets and centralised distribution systems.30,31 Foreign retailers have entered the Irish market providing discount prices, and low‐cost options such as own brand labels have appeared in various types of retail outlet. Although no analysis has been reported in Ireland, the nutritional quality of economy‐line foods compared with the market brand equivalent has been shown in the UK to be similar, if not better.32 In this study, the difference in retail cost of each basket type is not as marked as those found by Cooper and Nelson,32 where baskets of foods compiled using market brand lines were more than twice the cost of those compiled using economy‐line items. However, in the UK, data are based on a complete complement of food items available at economy‐line prices, whereas in Ireland, there is limited availability of own brand choices for many of the basket items. In those cases, market brand prices were used in calculating the total basket cost hence inflating the price of the own brand basket.

Own brand products are often available only in large quantities, resulting in the compulsion to buy more of any one item than may be required. Certainly, when products are durable, there is merit in purchasing them in large quantities. However, the underlying principle of having to outlay a substantial amount of money to obtain long‐term savings is not always feasible for low‐income groups. Also, the products are not always durable. Although large volumes may suit the larger family units, a small household unit will not require such volumes and can lead to food wastage, in addition to the financial outlay. The implication is that households with smaller requirements are at a retail cost disadvantage.

As in the UK,32,33,34,35 the foods recommended in the Irish healthy eating dietary guidelines are often more expensive than the less healthy options, and in four of the five shelves of the food pyramid, the own brand lines of the less healthy choice are even cheaper. By far, the cheapest place to purchase the food basket of each population group is in the Foreign outlet, but the range of items available is not exhaustive. The second least expensive place to purchase the basket of foods is in the Multiples, where the best range of food items is available with both market brand and own label pricing options. However, the retail outlet type used most often by low‐income groups is that of Groups/Symbols, followed by the more local independent traders.6,36 Such outlets have a limited selection of fruit, vegetables and wholemeal alternatives, not many low‐fat products and little or no fresh meat, fish and poultry, and stock every item from the top shelf of the food pyramid in the food baskets. This study shows that in a region of the Republic of Ireland, the type of outlets in which socially disadvantaged people shop are less likely to carry a good range of healthy foods and, when they do, they are more expensive.

Of concern are the large discrepancies found in the amount of money that low‐income groups would need to spend to purchase a diet in line with national dietary guidelines and the amount of money they have available to spend. Low‐cost but acceptable budget standards developed in other high‐income countries identified similar major shortfalls in the financial capacity of vulnerable populations, where the cost of a basket of goods required to live in a healthy manner exceeded the levels of social welfare benefit.16,17 Dobson et al37 highlighted how financially constrained households see food as a flexible item within the controllable household budget, and when other necessary household expenditure is taken into consideration, the food budget is reduced. On the basis of our findings, at current levels of financial resource, low‐income households in Ireland are probably not in a position to allocate the high expenditure necessary for healthy eating.

Study limitations

National‐level food costs and welfare benefits were used for the comparisons of food basket costs and household financial capacity, implying that the results reflect a general picture across the whole Republic of Ireland for these household types. The consistency of our findings with those from other countries suggests coherence and generalisability of our study. However, the retail outlet price variation was conducted only in Galway city. Galway contains the spectrum of Irish retail outlet types and the population demographics is not unlike that of other Irish urban areas. It could therefore be argued that the availability issues are generalisable to other areas in Ireland. However, to ensure that compositional and contextual issues are not misrepresented nor missed in terms of policy response, a systematic assessment must be undertaken of matters such as urban rural differences and indirect costs in purchasing a healthy diet relating to factors such as transport costs. This study relates to three distinct population groups. A similar investigation is now needed for other population groups, and the relative cost of the food baskets against differing financial scenarios. The pending report of a study on the standard of healthy living in Ireland (Friel et al,38 Food Safety Promotions Board) will begin to develop this evidence base through the provision of, on a regional basis across the island of Ireland, data on direct and indirect financial costs and availability of healthy food relative to other commodities and household income. The food budget standards presented in this paper do not currently account for food waste and may underestimate the cost of compliance with dietary guidelines. The extent of household food waste should be estimated in the Irish context and factored into the food budget standards. Although this study presents a case for minimum income standards to achieve healthy dietary choice, on the basis of equity, it is now timely to assess the other financial driver, food price, and how changes to it affect on dietary choice in rich countries such as the Republic of Ireland.

What this paper adds

This paper adds to the understanding of the wider determinants of dietary choices and highlights how even in an economically vibrant country, several population groups remain at risk of poor dietary intake because of macro‐economic processes and food supply issues.

The findings from this study reflect those in other rich countries; however, Ireland has a different retail structure and social policy framework.

It is important to obtain an evidence base within different contexts—similar issues but requiring a response suitable to the context.

It strengthens the argument for policy and practice responses to have a greater concentration on the distal causes of inequalities in health and health‐related behaviours.

Policy implications

Affordability of healthy food, having the financial capacity to purchase healthy food, physical access to retail outlets and the types of foods available for purchase is determined by social planning, health and food policy. The findings from this study provide robust scientific information with which policy planning should be informed.

Conclusions

Issues of financial access to and availability of healthy food options must be dealt with through national and international policies, cognisant of basic human needs for healthy living. Inadequate availability of low‐cost healthy options and readily available higher‐cost unhealthy options are strongly driving inequality in dietary choices of people living in Ireland. Although behavioural intervention at the individual level to discourage consumption of high‐fat, high‐sugar foods is necessary, this must be supported by structural and macropolicy‐level interventions. A greater selection of appropriately sized, reasonably priced healthy foods is needed. Given the flexible priority that food occupies within financially constrained households, it unlikely that the required allocation of household income to purchase food compliant with national dietary recommendations is obtainable unless more realistic financial provisions are made. Improvements in social welfare benefits and national wage agreements are needed, explicitly linked to a standard of adequacy and recognising the heterogeneity of needs in socially disadvantaged groups. These data provide a benchmark against which minimum‐income standards should be related, reflecting actual living costs associated with national health and food policy guidelines.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Central Statistics Office, particularly Jim Dalton, for his help with queries on the Household Budget Survey. We also thank the various retail outlets in Galway city that facilitated our collection of retail prices.

Abbreviations

MIS - minimum income standard

Footnotes

Funding: The Combat Poverty Agency's Research Initiative Programme funded this research.

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Balanda K, Wilde J.Inequalities in mortality: a report on all‐Ireland mortality data, 1989–1998. Dublin: Institute for Public Health, 2001

- 2.McElduff P, Dobson A. Trends in coronary heart disease—has the socioeconomic differential changed? Aust NZ J Public Health 200024465–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Friel S, Kelleher C, Nolan G.et al Social diversity of Irish adults nutritional status. Eur J Clin Nutr 200357865–875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nelson M. Childhood nutrition and poverty. Proc Nutr Soc 200059307–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.James W, Nelson M, Ralph A.et al The contribution of nutrition to inequalities in health. BMJ 19973141545–1549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Friel S, Conlon C.Food poverty and policy. Ireland: Combat Poverty Agency, 2004

- 7.Vincentian Partnership for Social Justice One long struggle. A study by of low‐income families. Dublin: The Vincentian Partnership for Social Justice, 2001

- 8.Hickey C, Downey D.Hungry for change: social exclusion, food poverty and homelessness in Dublin. Dublin: Focus Ireland, 2004

- 9.Dowler E, Dobson B. Nutrition and poverty in Europe: an overview. Nutr Soc 19975651–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shaw M, Dorling D, Gordon D.et alThe widening gap: health inequalities and policy in Britain. Bristol: The Policy Press, 1999

- 11.Dowler E. Food poverty and food policy. IDS Bull 19982958–65. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Steptoe A, Pollard T, Wardle J. Development of a measure of the motives underlying the selection of food: the Food Choice Questionnaire. Appetite 199525267–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.French S, Story M, Jeffery R. Environmental influences on eating and physical activity. Ann Rev Public Health 200122309–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Watson A.Food poverty: policy options for the new millennium. London: Sustain, 2001

- 15.Veit‐Wilson J.Dignity not poverty: a minimum income standard for the UK. London: Institute for Public Policy Research, 1994

- 16.Parker H.Low cost but acceptable. A minimum income standard for the UK: families with young children. Bristol: Policy Press, 1998

- 17.Saunders P.Using budget standards to assess the well‐being of families. Syndey: Social Policy Research Centre, 1998

- 18.Rowntree B.Poverty: a study of town life. London: Macmillan, 1901

- 19.Stitt S, Grant D. Food poverty: Rowntree revisited. NutrHealth 19949265–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Parker H. Low cost but acceptable. A minimum income standard for households with children in London's East End. York: Family Budget Unit, 2001

- 21.Nelson M, Dick K, Holmes B. Food budget standards and dietary adequacy in low‐income families. Proc Nutr Soc 200261569–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morris J, Donkin A, Wonderling D.et alA minimum income for healthy living. J Epidemiol Community Health 200054885–889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morris J, Deeming C. Minimum incomes for healthy living (MIHL): next thrust in UK social policy? Policy Politics 200432441–454. [Google Scholar]

- 24.FSAI Recommended dietary allowances for Ireland. Dublin: Food Safety Authority of Ireland, 1999

- 25.CSO Household Budget Survey 1999–2000. Detailed results for all households. Dublin: Central Statistics Office, 2001

- 26.Limerick Money Advice and Budgeting Service 101 Square meals. Limerick: Money Advice and Budgeting Service, 1998

- 27.Friel S, Nelson M, McCormack K.et al Methodological issues using Household Budget Survey expenditure data for individual food availability estimation: Irish experience in the DAFNE pan European project. J Public Health Nutr 200141143–1148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ministry of Agriculture Fisheries and Food Food portion sizes. London: HSMO, 1991

- 29.Department of Social and Family Affairs Social welfare rates of payment 2003. Dublin: Stationary Office, 2003

- 30.Flavian C, Haberberg A, Polo Y. Food retailing strategies in the European Union. A comparative analysis in the UK and Spain. J Retail Consumer Serv 20029125–138. [Google Scholar]

- 31.RGDATA Implications of superstores for Ireland. Dublin: RGDATA, 1998

- 32.Cooper S, Nelson M. Economy line foods from four supermarkets and brand name equivalents: a comparison of their nutrient contents and costs. J Hum Nutr Dietet 200316339–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sooman A, Macintyre S, Anderson A. Scotland's health—a more difficult challenge for some? The price and availability of healthy foods in socially contrasting localities in the West of Scotland. Health Bull 199351276–283. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Barratt J. The cost and availability of health food choices in southern Derbyshire. J Hum Nutr Dietet 19971063–69. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Food Commission Healthier diet costs more than ever. Food Mag 20005517 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Robinson N, Caraher M, Lang T. Access to shops: the views of low‐income shoppers. Health Educ J 200059121–136. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dobson B, Beardsworth A, Keil T.et alDiet, choice and poverty: social, cultural and nutritional aspects of food consumption among low‐income families. London: Family Policy Studies Centre, 1994

- 38.Friel S, Harrington J, Thunhurst C.et al Standard of Healthy Living on the Island of Ireland. Ireland: Food Safety Promotion Board, 2005