Abstract

Background and purpose:

Although participation of opioids in antinociception induced by cannabinoids has been documented, there is little information regarding the participation of cannabinoids in the antinociceptive mechanisms of opioids. The aim of the present study was to determine whether endocannabinoids could be involved in peripheral antinociception induced by activation of μ-, δ- and κ-opioid receptors.

Experimental approach:

Nociceptive thresholds to mechanical stimulation of rat paws treated with intraplantar prostaglandin E2 (PGE2, 2 μg) to induce hyperalgesia were measured 3 h after injection using an algesimetric apparatus. Opioid agonists morphine (200 μg), (+)-4-[(alphaR)-alpha-((2S,5R)-4-Allyl-2,5-dimethyl-1-piperazinyl)-3-methoxybenzyl]-N,N-diethylbenzamide (SNC80) (80 μg), bremazocine (50 μg); cannabinoid receptor antagonists N-(piperidin-1-yl)-5-(4-iodophenyl)-1-(2,4-dichlorophenyl)-4-methyl-1H-pyrazole-3-carboxamide (AM251) (20–80 μg), 6-iodo-2-methyl-1-[2-(4-morpholinyl)ethyl]-1H-indol-3-yl(4-methoxyphenyl) methanone (AM630) (12.5–100 μg); and an inhibitor of methyl arachidonyl fluorophosphonate (MAFP) (1–4 μg) were also injected in the paw.

Key results:

The CB1-selective cannabinoid receptor antagonist AM251 completely reversed the peripheral antinociception induced by morphine in a dose-dependent manner. In contrast, the CB2-selective cannabinoid receptor antagonist AM630 elicited partial antagonism of this effect. In addition, the administration of the fatty acid amide hydrolase inhibitor, MAFP, enhanced the antinociception induced by morphine. The cannabinoid receptor antagonists AM251 and AM630 did not modify the antinociceptive effect of SNC80 or bremazocine. The antagonists alone did not cause any hyperalgesic or antinociceptive effect.

Conclusions and implications:

Our results provide evidence for the involvement of endocannabinoids, in the peripheral antinociception induced by the μ-opioid receptor agonist morphine. The release of cannabinoids appears not to be involved in the peripheral antinociceptive effect induced by κ- and δ-opioid receptor agonists.

Keywords: Morphine, SNC80, bremazocine, CB1 receptor, CB2 receptor, peripheral antinociception

Introduction

Opioids are the drugs of choice for treating severe pain, despite the development of tolerance and dependence (Bhargava, 1994). They produce their pharmacological effects by acting mainly through three types of opioid receptors, namely μ, δ and κ (Singh et al., 1997). Cannabinoid receptor agonists also produce pain relief in a variety of animal models (Richardson, 2000). Two types of cannabinoid receptors have been identified. CB1 receptors are expressed primarily in central and peripheral neurons and CB2 receptors, mainly in immune cells (Pertwee, 2001, 2006; Howlett et al., 2002; Alexander et al., 2008). CB2 receptor expression in rat microglial cells (Carrier et al., 2004), in cerebral granule cells (Skaper et al., 1996), in mast cells (Samson et al., 2003) and in adult rat retina (Lu et al., 2000) has also been demonstrated. In the periphery, both receptors participate in pain control (Malan et al., 2001; Rice et al., 2002). In addition, receptors for opioids and cannabinoids are coupled to similar intracellular signalling mechanisms, mainly to a decrease in cAMP production through the activation of Gi proteins (Bidaut-Russell et al., 1990; Childers, 1991).

Since the discovery that opioids and cannabinoids produce not only several similar biochemical effects but also similar pharmacological effects, the interaction between these two classes of drugs has been extensively studied (Manzaneres et al., 1999). Many studies have indicated that cannabinoids can enhance the antinociceptive property of opioids. For example, the effects of morphine have been found to be enhanced by crude cannabis extracts (Ghosh and Bhattacharya, 1979). Synergism occurs at subeffective or submaximal doses of cannabinoid or opioid agonists and these effects are blocked by cannabinoid receptor (CB1) and opioid receptor antagonists (Reche et al., 1996; Smith et al., 1998). In addition, several studies have suggested that endogenous opioids might be involved in the regulation of pain control by cannabinoids. For example, intrathecally administered Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) has been shown to release endogenous opioid peptides (Pugh et al., 1996). Additionally, the cannabinoids, Δ9-THC and levonantradol appear to enhance the antinociceptive effect of morphine by releasing dynorphin A and dynorphin B, respectively (Welch and Eads, 1999). Moreover, a number of studies have indicated that opioid receptor antagonists might block cannabinoid-induced antinociception (Cox and Welch, 2004).

Anandamide, an endocannabinoid, is produced following intracellular cleavage of N-arachidonyl-phosphatidylethanolamine by phospholipase D and shows preferential affinity for CB1 receptors (Howlett et al., 2002). It is synthesized on demand instead of being stored in synaptic vesicles and is hydrolyzed to arachidonic acid and ethanolamine by a membrane bound enzyme named fatty acid amide hydrolase (FAAH) (Hohmann and Suplita, 2006). Mice lacking the FAAH gene exhibited enhanced antinociceptive behaviour, following administration of exogenous anandamide (Cravatt et al., 2001). One inhibitor of FAAH is methyl arachidonyl fluorophosphonate (MAFP) and this compound reacts irreversibly with FAAH (Deutsch et al., 1997) and thus enhances the responses induced by endocannabinoids (Ho and Randall, 2007).

The role of opioids in antinociception induced by cannabinoids has been observed; however, no information exists regarding the participation of cannabinoids in the antinociceptive mechanisms of opioids. Therefore, the aim of the present study was to determine whether endogenous cannabinoids could be involved in peripheral antinociception induced by activation of μ-, δ- and κ-opioid receptors through the use of cannabinoid receptor antagonists and a FAAH inhibitor.

Methods

Animals

All animal procedures and protocols were approved by the Ethics Committee on Animal Experimentation (CETEA) of the Federal University of Minas Gerais (UFMG).

The experiments were performed on 180–220 g male Wistar rats (N=5 per group) from the CEBIO-UFMG (The Animal Centre of the University of Minas Gerais). The rats were housed in a temperature-controlled room (23±1 °C) on an automatic 12-h light/dark cycle (0600–1800 hours of light phase). All testing was carried out during the light phase (0800–1500 hours). Food and water were freely available until the onset of the experiments.

Measurement of the hyperalgesia

After manual restraint, rats were s.c. injected with prostaglandin E2 (PGE2, 2 μg) into the plantar surface of its hindpaw and measured by the paw pressure test described by Randall and Selitto (1957). An analgesimeter (Ugo-Basile, Comerio, Italy) with a cone-shaped paw-presser with a rounded tip was used to apply a linearly increasing force to the rat's right hindpaw. The weight in grams required to elicit nociceptive responses, such as paw flexion or struggling, was determined as the nociceptive threshold. A cutoff value of 300 g was used to prevent damage to the paws. The nociceptive threshold was measured in the right paw and determined by the average of three consecutive trials recorded before (zero time) and 3 h after PGE2 injection (peak of hyperalgesic effect). The results are presented as the difference between these two averages (Δ of nociceptive threshold) and expressed as grams. To reduce stress, the rats were habituated to the apparatus 1 day before the experiments.

Experimental protocol

(+)-4-[(alphaR)-alpha-((2S,5R)-4-Allyl-2,5-dimethyl-1-piperazinyl)-3-methoxybenzyl]-N,N-diethylbenzamide (SNC80), morphine and bremazocine were given s.c. in the right hindpaw 1.5, 2 and 2.75 h after local injection of PGE2. Dose–response curves were determined for all opioid receptor agonists to determine effective doses for this study (data not shown). In the protocol used to determine whether the drugs were acting outside the injected paw, PGE2 was injected into both hindpaws, whereas morphine, SNC80 or bremazocine were administered into the left paw (data not shown).

N-(piperidin-1-yl)-5-(4-iodophenyl)-1-(2,4-dichlorophenyl)-4-methyl-1H-pyrazole-3-carboxamide (AM251) and 6-iodo-2-methyl-1-[2-(4-morpholinyl)ethyl]-1H-indol-3-yl(4-methoxyphenyl) methanone (AM630) were given s.c. 15 min before the measurement of hyperalgesia (3 h).

The nociceptive threshold was always measured in the right hindpaw. The protocol above was assessed in pilot experiments to determine the best moment for the injection of each substance.

Statistical analysis

Data were analysed statistically by one-way ANOVA with post hoc Bonferroni's test for multiple comparisons. Probabilities less than 5% (P<0.05) were considered to be statistically significant.

Materials

The following drugs and chemicals were used: PGE2 (Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA), morphine (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany), SNC80 (Tocris, Ellisville, MO, USA), bremazocine (RBI, Natick, MA, USA), AM251 (Tocris), AM630 (Tocris) and MAFP (Tocris). The drugs were dissolved as follows: PGE2 (ethanol 2%), morphine, SNC80 (dimethyl sulphoxide (DMSO) 8%), bremazocine (saline), AM251 (DMSO 12%), AM630 (DMSO 12%), MAFP (ethanol 3.2%), and injected in a volume of 100 μl per paw, with the exception of the AM251, AM630 and MAFP, which were injected in a volume of 50 μl per paw.

Results

Antagonism of morphine-induced antinociception by AM251

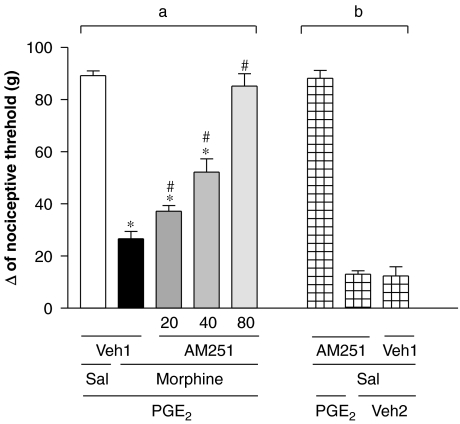

The intraplantar injection of the CB1 receptor antagonist AM251 (20, 40 and 80 μg) inhibited the morphine-induced peripheral antinociception (200 μg per paw) in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 1a). The highest dose of AM251, given without PGE2 or without morphine, did not induce hyperalgesia or antihyperalgesic effects (Figure 1b).

Figure 1.

Antagonism induced by intraplantar administration of AM251 of the peripheral antinociception produced by morphine in the hyperalgesic paw (PGE2, 2 μg). AM251 (20–80 μg) was administered 45 min after morphine (200 μg per paw) (a). This antagonist did not significantly modify the nociceptive threshold in control animals (b). Each column represents the mean±s.e.mean for five rats per group. *, #indicate significant differences compared with PGE2+Sal+Veh1- and PGE2+morphine+Veh1-injected groups, respectively (ANOVA+Bonferroni's test; F=60,9; df=4; P<0.0001). Veh1, vehicle1 (DMSO 12% in saline); Veh2, vehicle2 (ethanol 2% in saline); Sal, saline. AM251, N-(piperidin-1-yl)-5-(4-iodophenyl)-1-(2,4-dichlorophenyl)-4-methyl-1H-pyrazole-3-carboxamide; DMSO, dimethyl sulphoxide; PGE2, prostaglandin E2.

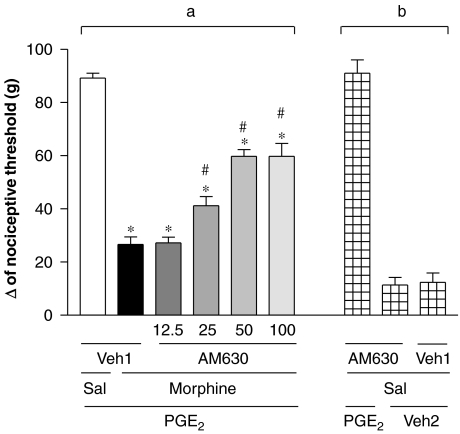

Antagonism of morphine-induced antinociception by AM630

The CB2 receptor antagonist AM630 (12.5, 25 and 50 μg) elicited partial antagonism of the peripheral antinociceptive effect of morphine (200 μg per paw; Figure 2a). Partial blockade was obtained even when using higher doses (100 μg per paw). This antagonist did not significantly modify the nociceptive threshold in control animals or induce any overt behavioural effect (Figure 2b).

Figure 2.

Antagonism induced by intraplantar administration of AM630 on the peripheral antinociception produced by morphine in the hyperalgesic paw (PGE2, 2 μg). AM630 (12.5–100 μg) was administered 45 min after morphine (200 μg per paw) (a). Given alone, this antagonist did not induce hyperalgesia or antihyperalgesic effects (b). Each column represents the mean±s.e.mean for five rats per group. *, #indicate significant differences compared with PGE2+Sal+Veh1- and PGE2+morphine+Veh1-injected groups, respectively (ANOVA+Bonferroni's test; F=60,0; df=5; P< 0.0001). Veh1, vehicle1 (DMSO 12% in saline); Veh2, vehicle2 (ethanol 2% in saline); Sal, saline. AM630, 6-iodo-2-methyl-1-[2-(4-morpholinyl)ethyl]-1H-indol-3-yl(4-methoxyphenyl) methanone; DMSO, dimethyl sulphoxide; PGE2, prostaglandin E2.

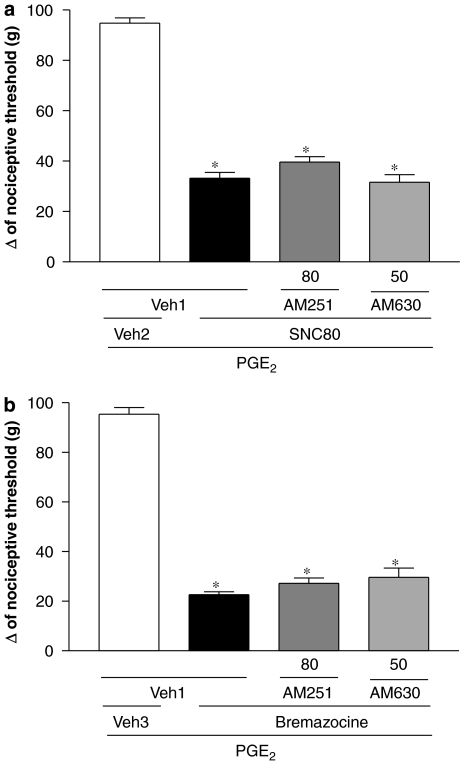

Effect of AM251 and AM630 on SNC80- or bremazocine-induced antinociception

As shown in Figure 3a, neither AM251 (80 μg per paw) nor AM630 (50 μg per paw) reduced the peripheral antinociceptive effect of SNC80 (80 μg per paw). AM251 (80 μg per paw) and AM630 (50 μg per paw) did not modify the peripheral antinociception of bremazocine (50 μg per paw; Figure 3b).

Figure 3.

Effect of intraplantar administration of AM251 and AM630 on the peripheral antinociception produced by SNC80 (a) or bremazocine (b) in the hyperalgesic paw (PGE2, 2 μg). AM251 (80 μg) or AM630 (50 μg) were administered 1:15 h after SNC80 (80 μg per paw) or at the same time as bremazocine (50 μg per paw). Each column represents the mean±s.e.mean for five rats per group. *indicate significant differences compared with PGE2+Veh1+Veh2- and PGE2+Veh1+SNC80/bremazocine-injected groups, respectively (ANOVA+Bonferroni's test; F=153,9; df=3; P<0.0001 (a) and F=176.5; df=3, P<0.0001 (b)). Veh1, vehicle1 (DMSO 12% in saline); Veh2, vehicle2 (DMSO 8% in saline); Veh 3, vehicle 3 (saline). AM251, N-(piperidin-1-yl)-5-(4-iodophenyl)-1-(2,4-dichlorophenyl)-4-methyl-1H-pyrazole-3-carboxamide; AM630, 6-iodo-2-methyl-1-[2-(4-morpholinyl)ethyl]-1H-indol-3-yl(4-methoxyphenyl) methanone; DMSO, dimethyl sulphoxide; PGE2, prostaglandin E2; SNC80, (+)-4-[(alphaR)-alpha-((2S,5R)-4-Allyl-2,5-dimethyl-1-piperazinyl)-3-methoxybenzyl]-N,N-diethylbenzamide.

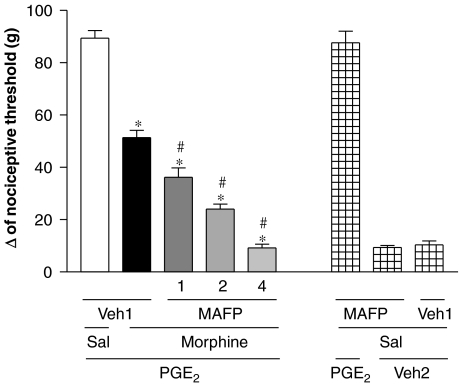

Increase of morphine-induced antinociception by MAFP

As shown in Figure 4, the administration of MAFP (1, 2 and 4 μg per paw) progressively enhanced the antinociception induced by a low dose of morphine (50 μg per paw). However, MAFP alone did not induce any effect.

Figure 4.

Potentiation of morphine-induced antinociception by MAFP in the hyperalgesic paw (PGE2, 2 μg). MAFP (1, 2 and 4 μg) was administered at the same time as morphine (50 μg per paw). MAFP given alone (4 μg) did not induce any nociceptive effect. Each column represents the mean±s.e.mean for five rats per group.*,#indicate a significant differences compared with PGE2+Veh1+Sal- and PGE2+Veh1+morphine-injected groups, respectively (ANOVA+Bonferroni's test; F=137.3; df=4; P<0.0001). Veh1, vehicle1 (DMSO 3.2% in saline); Veh2, vehicle 2 (ethanol 2% in saline); Sal, saline. DMSO, dimethyl sulphoxide; MAFP, methyl arachidonyl fluorophosphonate; PGE2, prostaglandin E2.

Discussion

The interaction between cannabinoids and opioids has been extensively studied and evidence exists that cannabinoid-induced antinociception may, to some extent, depend on the release of opioid peptides (Reche et al., 1996). Because little is known of the participation of endogenous cannabinoids in the analgesic mechanism of opioids, we have used here AM251 (a CB1 receptor antagonist) and AM630 (CB2 receptor antagonist) to characterize the role of endocannabinoids in peripheral antinociception induced by opioids.

Initially, the ability of the μ-, δ- and κ-opioid agonists, morphine (200 μg per paw), SNC80 (80 μg per paw) and bremazocine (50 μg per paw), respectively, to induce peripheral antinociception in the rat paw PGE2-induced hyperalgesia test was investigated. It is important to emphasize that these doses did not cause any central antinociceptive effect (data not shown).

Our results demonstrated that AM251 was able to prevent the peripheral antinociception induced by morphine, in a dose-dependent manner. AM251 is a potent CB1 receptor antagonist, 306-fold selective over CB2 receptors (Gatley et al., 1997; Lan et al., 1999). The participation of CB1 receptors in peripheral antinociception has been related in various studies (Rice et al., 2002). Additionally, intraplantar administration of CB1 agonist WIN55212-2 attenuated the development of carrageenan-evoked mechanical hyperalgesia and allodynia (Nackley et al., 2003). Recently, it was showed that by targeting CB1 receptors expressed on the peripheral axons of primary sensory neurons, substantial analgesia can be achieved in somatic and visceral pain, as well as in inflammatory and neuropathic pain (Agarwal et al., 2007). Moreover, one study provided strong evidence that peripheral CB1 receptors, presumed to be located on the peripheral endings of A- and C- fibre primary afferents, are able to modulate the transmission of innocuous and noxious somatosensory information from the periphery to the spinal cord (Kelly et al., 2003).

Many studies have shown that cannabinoids enhance the antinociception of morphine through the release of endogenous opioid peptides. For example, the cannabinoid Δ9-THC increased morphine antinociception by releasing dynorphin A (Welch and Eads, 1999). Another study demonstrated that naloxone blocked the synergistic antinociception produced by low oral doses of Δ9-THC and morphine, indicating the involvement of the μ-opioid receptor in this effect (Cichewicz et al., 1999). Recently, it was suggested that CB1- and μ-opioid receptors form heterodimers (Rios et al., 2006). Heterodimer formation is needed for the function of certain G-protein-coupled receptors, for example, the GABAB receptor (Ong and Kerr, 2000).

The CB2 receptor antagonist AM630 partially blocked the peripheral antinociception induced by morphine. AM630 is a CB2-selective ligand that behaves as an antagonist/inverse agonist at CB2 receptors and is 165-fold selective over CB1 receptors (Ross et al., 1999). The CB2 receptor is primarily located on immune cells in the periphery (Galiègue et al., 1995) and studies have demonstrated the presence of CB2 receptors in a number of brain regions, contrary to the prevailing view that they are restricted to peripheral tissues (Sickle et al., 2005; Gong et al., 2006; Onaivi et al., 2006). These receptors have not been found on peripheral neurons, suggesting that the activation of CB2 receptors produces antinociception indirectly, by causing the release of mediators from non-neuronal cells that alter the responsiveness of primary afferent neurons to noxious stimuli. One cell type that might mediate the actions of CB2 receptor-selective agonists is the keratinocyte, which has been reported to express CB2 receptors (Casanova et al., 2003) and to contain endogenous opioid peptides (Kauser et al., 2003). Antinociception produced by CB2 receptor-selective agonists may be mediated by the stimulation of β-endorphin release from cells with these receptors. The β-endorphin thus released appears to act at μ-opioid receptors, probably on the terminals of primary afferent neurons, to produce peripheral antinociception (Ibrahim et al., 2005). Another study has shown that intraplantar administration of the CB2 receptor agonist, AM1241, reduces thermal nociception. Moreover, the antinociceptive actions of systemic AM1241 were blocked by injection of AM630 into the paw where the thermal stimulus was applied. These findings demonstrate the local, peripheral nature of the antinociception mediated through CB2 receptors (Malan et al., 2001). Additionally, local peripheral activation of CB2 receptors attenuates innocuous and noxious mechanically evoked responses of spinal wide dynamic range neurons in models of acute inflammatory and neuropathic pain (Elmes et al., 2004). Also, inhibitory effects of anandamide in rats with hindpaw inflammation were blocked by the co-injection of the CB2 receptor antagonist SR144528. These data indicate that, under these conditions, the inhibitory effects of anandamide are mediated predominantly by peripheral CB2 receptors (Sokal et al., 2003). There are no studies demonstrating the participation of CB2 receptors in the effects of opioids.

To confirm the participation of endocannabinoids in the peripheral antinociceptive actions of morphine, we used MAFP, an irreversible inhibitor of FAAH, the enzyme responsible for hydrolysis and inactivation of the endocannabinoid anandamide. The current results demonstrated that administration of MAFP enhanced the peripheral antinociception produced by a low dose of morphine (50 μg per paw), suggesting that activation of μ-opioid receptors induced the release of endocannabinoids. Anandamide is an agonist at CB1 and CB2 receptors, but has greater affinity for CB1 receptors (Howlett et al., 2002) and the present work showed that the antinociceptive effect of morphine was completely reversed by the CB1 receptor antagonist AM251 and only partially reversed by the CB2 receptor antagonist AM630. It has been proposed that anandamide is rapidly inactivated by a re-uptake system consisting of the anandamide membrane transporter, which transports anandamide into cell where it is hydrolyzed (Di Marzo et al., 1994). Although FAAH appears to be the enzyme primarily responsible for the hydrolysis of anandamide, another acid amidase has been identified that is also capable of hydrolyzing anandamide (Ueda et al., 2001). Notably, the compound MAFP, which is often used to inhibit FAAH, has been found to be a potent inhibitor of monoacylglycerol lipase activity (Dinh et al., 2002). The crucial role of FAAH and monoacylglycerol lipase in the inactivation of anandamide suggests that inhibitors of these enzymes could be utilized to enhance endocannabinoid activity (Ho and Randall, 2007). The endocannabinoids involved in pain modulation have been identified directly using microdialysis and liquid and/or gas chromatography mass spectrometry (Cravatt et al., 2001; Cravatt and Lichtman, 2002) and indirectly by administration of pharmacological agents that regulate endocannabinoid uptake or degradation (Hohmann and Suplita, 2006). The present study focused on the indirect approach. Nevertheless, the direct measurement of endocannabinoid levels in paw tissue would have been very desirable and should be the subject of future work. Additionally, MAFP affects activities of cPLA2, iPLA2 and COX (Huang et al., 1994, 1996), but it binds irreversibly and with greater affinity to anandamide amidase than it does to other amide hydrolytic enzymes or to the cannabinoid receptor CB1 (Deutsch et al., 1997). Also, intrathecal administration of MAFP dose-dependently prevented thermal hyperalgesia induced by intraplantar carragenan, as well as formalin-induced flinching (Lucas et al., 2005). Moreover, the co-injection of AM251 with MAFP in the formalin test completely reversed the MAFP-induced antinociception, indicating that this effect is mediated by CB1 receptors (Ates et al., 2003). Our data showed that, in the experimental model utilized, MAFP alone did not alter the hyperalgesia induced by PGE2. On the other hand, the FAAH inhibitor URB597 significantly attenuated mechanically evoked responses of spinal neurons in sham-operated rats. In contrast, in neuropathic rats, the same intraplantar dose of URB597 had no effect, although a higher dose attenuated responses of spinal neurons, without increasing the levels of endocannabinoids (Jhaveri et al., 2006). These authors suggested that the contribution of FAAH to endocannabinoid metabolism is altered in models of neuropathic pain.

In contrast to morphine, AM251 and AM630 did not exert an effect on peripheral antinociception induced by SNC80 or bremazocine at effective doses. On the other hand, some studies have demonstrated that intrathecally administered cannabinoids evoke the release of endogenous opioids that stimulate δ- and κ-opioid receptors to produce antinociception (Welch, 1993; Pugh et al., 1996). Other studies have shown that μ-receptors and, preferentially, κ-receptors, but not δ-receptors, are involved in the antinociceptive action of Δ9-THC (Reche et al., 1996). There are no studies on the participation of cannabinoids in the outcome of activation of κ- and δ-opioid receptors.

In conclusion, the present data showed, for the first time, that the antinociceptive effects of agonists at the μ- but not at the κ- or δ-opioid receptors were blocked by CB1 and, at least in part, CB2 receptor antagonists, suggesting that activation of these CB receptors by endocannabinoids contributes to the analgesic effects of opioid analgesics in a model of inflammatory hyperalgesia. However, more work needs to be carried out to elucidate this new interaction between opioids and cannabinoids.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for fellowships by CAPES (Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior) and CNPq (Conselho Nacional de Pesquisa).

Abbreviations

- AM251

N-(piperidin-1-yl)-5-(4-iodophenyl)-1-(2,4-dichlorophenyl)-4-methyl-1H-pyrazole-3-carboxamide

- AM630

6-iodo-2-methyl-1-[2-(4-morpholinyl)ethyl]-1H-indol-3-yl(4-methoxyphenyl) methanone

- MAFP

methyl arachidonyl fluorophosphonate/(5Z,8Z,11Z,14Z)-5,8,11,14-eicosatetraenyl-methyl ester phosphonofluoridic acid

- PGE2

prostaglandin E2

- SNC80

(+)-4-[(alphaR)-alpha-((2S,5R)-4-Allyl-2,5-dimethyl-1-piperazinyl)-3-methoxybenzyl]-N,N-diethylbenzamide

Conflict of interest

The authors state no conflict of interest.

References

- Agarwal N, Pacher P, Tegeder I, Amaya F, Constantin CE, Brenner GJ. Cannabinoids mediate analgesia largely via peripheral type 1 cannabinoid receptors in nociceptors. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:870–879. doi: 10.1038/nn1916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander SPH, Mathie A, Peters JA. Guide to Receptors and Channels (GRAC), 3rd edn. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;153 Suppl. 2:S1–S209. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ates M, Hamza M, Seidel K, Kotalla CE, Ledent C, Guhring H. Intrathecally applied flurbiprofen produces an endocannabinoid-dependent antinociception in the rat formalin test. Eur J Neurosci. 2003;17:597–604. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02470.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhargava HN. Diversity of agents that modify opioid tolerance. Physical dependence, abstinence syndrome and self administrative behavior. Pharmacol Rev. 1994;46:293–323. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bidaut-Russell M, Devane WA, Howlett AC. Cannabinoid receptors and modulation of cyclic AMP accumulation in the rat brain. J Neurochem. 1990;55:21–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1990.tb08815.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrier EJ, Kearn CS, Barkmeier AJ, Breese NM, Yang W, Nithipatikom K, et al. Cultured rat microglial cells synthesize the endocannabinoid 2-arachidonylglycerol, which increases proliferation via a CB2 receptor-dependent mechanism. Mol Pharmacol. 2004;65:999–1007. doi: 10.1124/mol.65.4.999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casanova ML, Blázquez C, Martínez-Palacio J, Villanueva C, Fernández-Aceñero MJ, Huffman JW, et al. Inhibition of skin tumor growth and angiogenesis in vivo by activation of cannabinoid receptors. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:43–50. doi: 10.1172/JCI16116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Childers SR. Opioid receptor-coupled second messengers. Life Sci. 1991;48:1991–2003. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(91)90154-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cichewicz DL, Martin ZL, Smith FL, Welch SP. Enhancement mu opioid antinociception by oral Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol: dose–response analysis and receptor identification. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1999;289:859–867. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox ML, Welch SP. The antinociceptive effect of Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol in the arthritic rat. Eur J Pharmacol. 2004;493:65–74. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2004.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cravatt BF, Demarest K, Patricelli MP, Bracey MH, Giang DQ, Martin DR, et al. Supersensitivity to anandamide and enhanced endogenous cannabinoid signaling in mice lacking fatty acid amide hydrolase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:9371–9376. doi: 10.1073/pnas.161191698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cravatt BF, Lichtman AH. The enzymatic inactivation of the fatty acid amide class of signaling lipids. Chem Phys Lipids. 2002;121:135–148. doi: 10.1016/s0009-3084(02)00147-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deutsch DG, Omeir R, Arreaza G, Salehani D, Prestwich GD, Huang Z, et al. Methyl arachidonyl fluorophosphonate: a potent irreversible inhibitor of anandamide amidase. Biochem Pharmacol. 1997;53:255–260. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(96)00830-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Marzo V, Fontana A, Cadas H, Schinelli S, Cimino G, Swhawartz JC, et al. Formation and Inactivation of endogenous cannabinoid anandamide in central neurons. Nature. 1994;372:686–691. doi: 10.1038/372686a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinh TP, Freund TF, Piomelli D. A role for monoglyceride lipase in 2-arachidonoylglycerol inactivation. Chem and Phys of Lip. 2002;121:149–158. doi: 10.1016/s0009-3084(02)00150-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elmes SJR, Jhaveri MD, Smart D, Kendall DA, Chapman V. Cannabinoid CB2 receptor activation inhibits mechanically evoked responses of wide dynamic range dorsal horn neurons in naive and in rat models of inflammatory and neuropatic pain. Eur J Neurosci. 2004;20:2311–2320. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03690.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galiègue S, Mary S, Marchand J, Dussossoy D, Carrière D, Carayon P, et al. Expression of central and peripheral cannabinoid receptors in human immune tissues and leukocyte subpopulations. Eur J Biochem. 1995;232:54–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1995.tb20780.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gatley SJ, Lan R, Pyatt B, Gifford AN, Volkow ND, Makriyannis A. Binding of the non-classical cannabinoid CP 55,940, and the diarylpyrazole AM251 to rodent brain cannabinoid receptors. Life Sci. 1997;61:191–197. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(97)00690-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh P, Bhattacharya SK. Cannabis-induced potentiation of morphine analgesia in rat: role of brain monoamines. Ind J Med Res. 1979;70:275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong JP, Onaivi ES, Ishiguro H, Liu QR, Tagliaferro PA, Brusco A, et al. Cannabinoid CB2 receptors: immunohistochemical localization in rat brain. Brain Res. 2006;1071:10–23. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.11.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho WSV, Randall MD. Endothelium-dependent metabolism by endocannabinoid hydrolases and cyclooxygenases limits vasorelaxation to anandamide and 2-arachidonoylglycerol. Br J Pharmacol. 2007;150:641–651. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hohmann AG, Suplita RL. Endocannabinoid mechanisms of pain modulation. AAPS J. 2006;8:693–708. doi: 10.1208/aapsj080479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howlett AC, Barth F, Bonner TI, Cabral G, Casellas P, Devane WA, et al. International Union of Pharmacology XXVII. Classification of cannabinoid receptors. Pharmacol Rev. 2002;54:161–202. doi: 10.1124/pr.54.2.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Z, Liu S, Laliberte F, Quellets M, Desmaka S, Abdullah K, et al. Methyl arachidonyl fluorophosphonate, a potent irreversible cPLA2 inhibitor, blocks the mobilization of arachidonic acid in human platelets and neutrophils. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 1994;72:711–715. [Google Scholar]

- Huang Z, Payette P, Abdullah K, Cromlish WA, Kennedy BP. Functional identification of the active-site nucleophile of the human 85-kDa cytosolic phospholipase A2. Biochemistry. 1996;35:3712–3721. doi: 10.1021/bi952541k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim MM, Porreca F, Lai J, Albrecht J, Rice FL, Khodorova A, et al. CB2 cannabinoid receptor activation produces anti-nociception by stimulating peripheral release of endogenous opioids. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:3093–3098. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409888102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jhaveri MD, Richardson D, Kendall DA, Barret DA, Chapman V. Analgesic effects of fatty acid amide hydrolase inhibition in a rat model of neuropathic pain. J Neurosci. 2006;26:13318–13327. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3326-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kauser S, Schallreuter KU, Thody AJ, Gummer C, Tobin DJ. Regulation of human epidermal melanocyte biology by beta-endorphin. J Invest Dermatol. 2003;120:1073–1080. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2003.12242.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly S, Jhaveri MD, Sagar DR, Kendall DA, Chapman V. Activation of peripheral cannabinoid CB1 receptors inhibits mechanically evoked responses of spinal neurons in non inflamed rats and rats with hindpaw inflammation. Eur L Neurosci. 2003;18:2239–2243. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02957.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lan R, Liu Q, Fan P, Lin S, Fernando SR, McCallion D, et al. Structure-activity relationships of pyrazole derivatives as cannabinoid receptor antagonists. J Med Chem. 1999;42:769–776. doi: 10.1021/jm980363y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Q, Straiker A, Lu Q, Maguire G. Expression of CB2 cannabinoid receptor mRNA in adult rat retina. Vis Neurosci. 2000;17:91–95. doi: 10.1017/s0952523800171093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas KK, Svensson CI, Hua XY, Yaksh TL, Dennis EA. Spinal phospholipase A2 in inflammatory hyperalgesia: role of group IVA cPLA2. Br J Pharmacol. 2005;144:940–952. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malan TP, Ibrahim MM, Deng H, Liu Q, Mata HP, Vanderah T, et al. CB2 cannabinoid receptor-mediated peripheral antinociception. Pain. 2001;93:239–245. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(01)00321-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manzaneres J, Corchero J, Romero JJ, Fernandez-Ruiz JA, Ramos JÁ, Fuentes JA. Pharmacological and biochemical interactions between opioids and cannabinoids. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1999;20:287–294. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(99)01339-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nackley AG, Suplita RL, Hohmann AG. A peripheral cannabinoid mechanism suppresses spinal fos protein expression and pain behavior in a rat model of inflammation. Neurosci. 2003;117:659–670. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00870-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onaivi ES, Ishiguro H, Gong JP, Patel S, Perchuk A, Meozzi PA, et al. Discovery of the presence and functional expression of cannabinoid CB2 receptors in brain. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006;1074:514–536. doi: 10.1196/annals.1369.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ong J, Kerr DI. Recent advances in GABAB receptors: from pharmacology to molecular biology. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2000;21:111–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pertwee RG. Cannabinoid receptors and pain. Prog Neurobiol. 2001;63:569–611. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(00)00031-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pertwee RG. Cannabinoid pharmacology; the first 66 years. Br J Pharmacol. 2006;147:S163–S171. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pugh G, Smith PB, Dombrowski DS, Welch SP. The role of endogenous opioids in enhancing the antinociception produced by the combination of delta 9-tetrahydrocannabinol and morphine in the spinal cord. J Pharmacol Exp Therm. 1996;279:608–616. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Randall ID, Selitto JJ. A method for measurement of analgesic activity on inflamed issues. Arch Int Phar Ther. 1957;113:233–249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reche I, Fuentes JA, Ruiz-Gaio M. Potentiation of Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol-induced analgesia by morphine in mice: involvement of μ and κ opioid receptors. Eur J Pharmacol. 1996;318:11–16. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(96)00752-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice AS, Farquhar-Smith WP, Nagy I. Endocannabinoids and pain: spinal and peripheral analgesia in inflammation and neuropathy. Prostaglandin Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2002;66:243–256. doi: 10.1054/plef.2001.0362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson JD. Cannabinoids modulate pain by multiple mechanisms of action. J Pain. 2000;1:2–14. [Google Scholar]

- Rios C, Gomes I, Devi LA. mu opioid and CB1 cannabinoid receptor interactions: reciprocal inhibition of receptor signaling and neuritogenesis. Br J Pharmacol. 2006;148:387–395. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross RA, Brockie HC, Stevenson LA, Murphy VL, Templeton F, Makriyannis A, et al. Agonist-inverse agonist characterization at CB1 and CB2 cannabinoid receptors of L759633, L759656, and AM630. Br J Pharmacol. 1999;126:665–672. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samson MT, Small-Howard A, Shimoda LM, Koblan-Huberson M, Stokes AJ, Turner H. Differential roles of CB1 and CB2 cannabinoid receptors in mast cells. J Immunol. 2003;170:4953–4962. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.10.4953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sickle MDV, Duncan M, Kingsley PJ, Mouihate A, Urbani P, Mackie K, et al. Identification and functional characterization of brainstem cannabinoid CB2 receptors. Science. 2005;310:329–332. doi: 10.1126/science.1115740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh VK, Bajpai K, Biswas S, Haq W, Khan MY, Mathur KB. Molecular biology of opioid receptors: recent advances. Neuroimmunomodulation. 1997;4:285–297. doi: 10.1159/000097349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skaper SD, Buriani A, Dal Toso R, Petrelli L, Romanello S, Facci L, et al. The Aliamide palmitoylethanolamide and cannabinoids, but not anandamide, are protective in a delayed postglutamate paradigm of excitotoxic death in cerebral granule neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:3984–3989. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.9.3984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith FL, Cichewiez D, Martin ZL, Welch SP. The enhancement of morphine antinociception in mice by delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1998;60:559–566. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(98)00012-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sokal DM, Elmes SJR, Kendall DA, Chapman V. Intraplantar injection of anandamide inhibits mechanically-evoked responses of spinal neurones via activation of CB2 receptors in anaesthetised rats. Neuropharmacol. 2003;45:404–411. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(03)00195-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueda N, Yamanaka K, Yamamoto S. Purification and characterization of an acid amidase selective for N-palmitoylethanolamine, a putative endogenous anti-inflammatory substance. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:35552–35557. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106261200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welch SP. Blockade of cannabinoid-induced antinociception by norbinaltorphimine, but not N,N-diallyl-tyrosine-Aib-phenylalanine-leucine, ICI 174864 or naloxone in mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1993;265:633–640. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welch SP, Eads M. Synergistic interactions of endogenous opioids and cannabinoids systems. Brain Res. 1999;848:183–190. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)01908-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]