Abstract

Background

Nerve, nerve root and plexus disorders are common diseases, but little is known about familial clustering in these diseases. This is, to our knowledge, the first systematic family study carried out on these diseases.

Methods

Familial risks for siblings who were hospitalised for nerve, nerve root and plexus disorders in Sweden were defined. A nationwide database for neurological diseases was constructed by linking the Multigeneration Register on 0–69‐year‐old siblings to the Hospital Discharge Register covering the years 1987–2001. Standardised risk ratios (SIRs) were calculated for affected sibling pairs by comparing them with those whose siblings had no neurological disease.

Results

29 686 patients, 43% men and 57% women, were diagnosed at a mean age of 37.5 years. 191 siblings were hospitalised for these disorders, giving an overall SIR of 2.59 (95% CI 1.58 to 4.22), with no sex difference. Plantar nerve mononeuritis and carpal tunnel syndrome showed the highest familial risks: 4.82 (1.08 to 16.04) and 4.08 (2.07 to 7.84), respectively. Lateral poplitean and plantar nerve neuritis preferentially affected women, with SIRs of >8; disorders of the other cranial nerves affected only men, with an SIR of >10. Concordant trigeminal neuralgia, Bell's palsy and carpal tunnel syndrome showed familial risks, but, with the exception of Bell's palsy, they also showed correlation between spouses, implying environmental sharing of risk factors.

Conclusions

The results cannot distinguish between inheritable or shared environmental factors, or their interactions, but they clearly show familial clustering, suggestive of multifactorial aetiology and inviting for aetiological research.

According to the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) version 10, nerve, nerve root and plexus disorders cover diseases of the cranial and peripheral nerves, affecting a single nerve (mononeuropathy or mononeuritis), multiple nerves or nerves of a plexus (plexopathy).1 Polyneuropathies, such as Guillain–Barré syndrome, are not included in this subclassification. Nerve, nerve root and plexus disorders belong to some of the most common neurological diseases, and they share symptoms with even more common conditions, such as low back pain. The most commonly diagnosed diseases include trigeminal neuralgia (pain in the face),2 Bell's palsy (unilateral facial weakness),3 brachial and other plexus disorders, and mononeuropathies of the arms and legs, of which carpal tunnel syndrome of the median nerve and cubital tunnel syndrome of the ulnar nerve are the most common.4 Carpal tunnel syndrome is an important cause of work disability, and has been the subject of many studies.5,6 The aetiology of this group of neurological disease is either unknown (idiopathic) or known (symptomatic), and the symptomatic aetiology includes causes such as trauma, viral infection, vascular or ischaemic lesions, tumours, chronic disease or, in the case of entrapment neuropathies, monotonous repeated movements.1 Data on familial clustering of a disease are practically the only way to assess its inheritability, provided that environmental causes for the clustering can be excluded.7 Familial syndromes for nerve, nerve root and plexus disorders are rare, and the genetic basis has been characterised only for hereditary neuralgic amyotrophy.8,9 Familial clustering of some diseases have been described in case reports,1,10,11,12 but formal epidemiological studies on familial clustering are rare.13 Family studies are important for understanding the disease aetiology. If evidence for familial clustering is found, environmental and inheritable causes would need to be distinguished. A demonstration of an inheritable cause would give an incentive for gene mapping and identification efforts. Similarly, an environmental aetiology would need to be characterised and quantified.

In this cohort study, we systematically compared familial risks for nerve, nerve root and plexus disorders within and between the disease groups, on the basis of disease‐specific data on all hospitalisations in Sweden. We analysed risks between siblings aged 0–69 years who were hospitalised for these diseases. Nerve, nerve root and plexus disorders do not always require hospitalisation, but those that do probably belong to severe forms of the disease. The hospital data have an advantage that all patients have been seen by several doctors, including specialists. The usefulness of the Swedish family dataset has been shown previously in studies of familial migraine and aortic aneurysms.14,15 We also analysed the risks between spouses, because correlation between spouses would be an indication of environmental causes for familial clustering.

Participants and methods

The research database used for this study, the neurological database, is a subset of the national MigMed database at Karolinska Institute, Centre for Family Medicine, Huddinge, Sweden. The MigMed database was compiled using data from several national Swedish registers provided by Statistics Sweden, including the Multigeneration Register in which people (second generation) born in Sweden from 1932 onwards are registered shortly after birth and are linked to their biological parents (first generation). Sibships could only be defined for the second generation, which was this study population. National Census Data (1960–90) and the Swedish population register (1990–2001) were incorporated into the database to obtain information on individuals' socioeconomic status. Dates of hospitalisation for neurological diseases were obtained during the study period from the Swedish Hospital Discharge Register. Since 1986, complete data on all discharges, with dates of hospitalisation and diagnoses, have been recorded in this register. All patients registered for hospitalisation stayed at least one night in the hospital, usually in wards with neurology consultants or in neurology departments; the register does not include outpatients in hospitals or healthcare centres. In the hospital discharge register, diagnoses were reported according to Versions 9 (1987–96) and 10 (1997–2001) of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD), classified into six groups of diseases and by specific diagnosis, as table 1 shows, using the ICD codes. Fortunately, the classification of the studied diseases was equivalent in the two ICD versions. Only the first hospitalisation was considered when a neurological disease was given as the main diagnosis; thus, nerve, nerve root and plexus disorders secondary to another disease were not likely to be included. Another reason for considering only the first hospitalisation was an attempt to limit selection bias; once a patient has entered a hospital and medical surveillance, the likelihood of a new diagnosis is increased. All linkages were performed using the national 10‐digit civic identification number that is assigned to each person in Sweden for his or her lifetime. This number was replaced by a serial number for each person to provide anonymity and to check that each individual was entered only once for their first hospitalisation of a neurological disease. About 6.9 million individuals were included in the second generation of the neurological database.

Table 1 Description of the study population of patients hospitalised for nerve, nerve root and plexus disorders.

| Subtype (ICD9/10 codes) | Men | Women | All | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Mean (SD) age | IR | n | Mean (SD) age | IR | n | Mean (SD) age | IR | |

| Disorders of the trigeminal nerve (350/G50) | 408 | 45.2 (14.1) | 1.1 | 651 | 45.4 (12.6) | 1.9 | 1059 | 45.3 (13.2) | 1.5 |

| Trigeminal neuralgia (350.A, 350.B/G50.0) | 270 | 49.1 (12.1) | 0.9 | 394 | 48.4 (11.9) | 1.3 | 664 | 48.7 (12.0) | 1.1 |

| Facial nerve disorders (351/G51) | 1837 | 29.8 (19.8) | 4.3 | 2033 | 28.2 (19.1) | 4.6 | 3870 | 28.9 (19.5) | 4.5 |

| Bell's palsy (351.A/G51.0) | 1639 | 29.2 (19.9) | 3.8 | 1818 | 27.4 (19.1) | 4.1 | 3457 | 28.2 (19.5) | 4.0 |

| Disorders of other cranial nerves (352/G52, G53) | 193 | 38.1 (18.3) | 0.5 | 167 | 36.9 (17.5) | 0.4 | 360 | 37.5 (17.9) | 0.4 |

| Nerve root and plexus disorders (353/G54, G55) | 793 | 38.9 (14.8) | 1.7 | 939 | 38.7 (13.7) | 2.0 | 1732 | 38.8 (14.2) | 1.8 |

| Mononeuritis of the upper limb and mononeuritis multiplex (354/G56, G58) | 2312 | 41.7 (11.3) | 5.0 | 3142 | 40.9 (11.2) | 6.8 | 5454 | 41.2 (11.3) | 5.9 |

| Carpal tunnel (354.A/G56.0) | 672 | 42.2 (11.5) | 1.5 | 1578 | 41.8 (11.2) | 3.5 | 2250 | 41.9 (11.3) | 2.5 |

| Mononeuritis of the lower limb (355/G57) | 729 | 38.7 (12.3) | 1.5 | 1111 | 39.0 (13.4) | 2.4 | 1840 | 38.9 (12.9) | 2.0 |

| All types | 8853 | 37.6 (16.1) | 14.1 | 11833 | 37.4 (15.5) | 18.2 | 20686 | 37.5 (15.7) | 16.1 |

ICD, International Classification of Diseases; IR, index of response.

Statistical analysis

Person‐years were calculated from start of follow‐up on 1 January 1987 until hospitalisation for the first neurological disease, death, emigration or the closing date (31 December 2001). Age‐specific incidence rates were calculated for the whole follow‐up period, divided into five 5‐year periods. Standardised incidence ratios (SIRs) were calculated as the ratio of observed to expected number of cases. The expected number of cases was calculated for age (5‐year groups), sex, period (5‐year groups), region (three areas) and socioeconomic status‐specific (six categories: farmer, unskilled worker, skilled worker, professional, self‐employed and other) standard incidence rates among those who did not have an affected sibling; all these factors may influence the rate of hospitalisation for nerve, nerve root and plexus disorders and may thus confound the familial risk. Information on the occupational titles of the subjects was also available, and some analyses were carried out using this. Sibling risks were calculated for men and women with siblings affected with concordant (same) or discordant (different) neurological diseases, compared with men and women whose siblings were not affected by these conditions, using the cohort methods as described.16 In rare families where more than two siblings were affected, each was counted as an individual patient. Confidence intervals (95% CI) were calculated assuming a Poisson distribution, and were adjusted for dependence between the sibling pairs.16 Spouses were defined through common children. In this study and in the global literature on familial risks, the risk estimates are usually >1 because it is conceivable that even one affected family member signals the likelihood of risk compared with families with no affected individuals. However, familial cases were rare and did not contribute much to the overall risk estimates.

Results

We analysed risks for siblings aged 0–69 years who were hospitalised for nerve, nerve root and plexus disorders in Sweden between 1987 and 2001 from a population of 7 million individuals. A total of 29 686 patients, 43% men and 57% women, were diagnosed at a mean age of 37.5 years (table 1). Mononeuritis of the upper limb and mononeuritis multiplex was the largest subtype, with 5454 patients, and in this subtype, carpal tunnel syndrome was the most common diagnosis with 2250 patients, of which 70% were women. Overall, Bell's palsy with 3457 patients was the most common diagnosis; this corresponded to a hospitalisation rate of 4 per 100 000 person‐years. Nerve root and plexus disorders were one of the smallest subtypes. Female patients outnumbered male patients for all other subtypes except disorders of other cranial nerves, the rarest subtype. The overall diagnostic age was 37.5 years, and it ranged between 28.2 years for Bell's palsy and 48.7 years for trigeminal neuralgia. Similar data were also collected for familial cases (two siblings affected with nerve, nerve root and plexus disorders (data not shown)). Their mean diagnostic ages were about 3 years older than those for all patients.

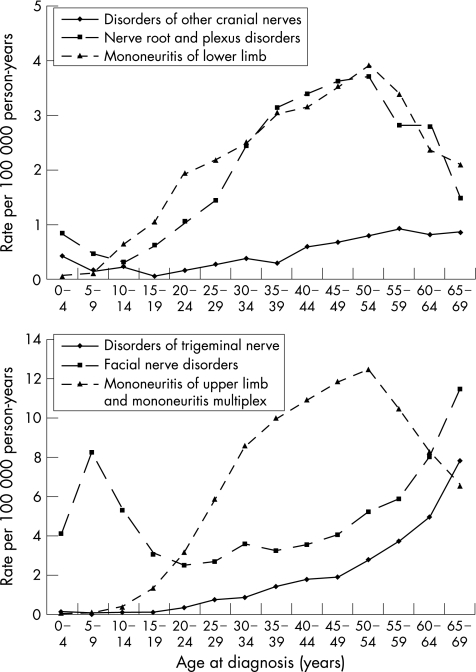

Figure 1 shows age‐specific hospitalisation rates for the different subtypes of nerve, nerve root and plexus disorders for men and women combined, because the shapes of the age–incidence curves did not differ between the sexes. Three types of patterns for the age–incidence curves were observed: facial nerve disorders showed an early‐onset maximum (5–9 years) and a late‐onset maximum (>65 years); disorders of the trigeminal nerve showed only the late‐onset maximum (>65 years); all other subtypes showed a broad middle‐age maximum (45–54 years).

Figure 1 Age‐specific hospitalisation rates for the different subtypes of nerve, nerve root and plexus disorders for men and women.

Table 2 shows sibling risks for subtypes of nerve, nerve root and plexus disorders when the co‐sibling was diagnosed with any of these diseases. A total of 191 siblings were hospitalised for nerve, nerve root and plexus disorders, giving an overall SIR of 2.59. In both sexes combined, plantar nerve mononeuritis and carpal tunnel syndrome showed the highest familial risks: 4.82 and 4.08, respectively. Lateral poplitean (posterior surface of the knee) and plantar nerve (sole) neuritis preferentially affected women with SIRs of >8.0. On the other hand, disorders of the other cranial nerves affected only men with an SIR of 10.41.

Table 2 Familial standardised incidence ratios for subtypes of nerve, nerve root and plexus disorders when sibling was diagnosed with any of these diseases.

| Subtypes in offspring | Men | Women | All | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| O | SIR (95% CI) | O | SIR (95% CI) | O | SIR (95% CI) | |

| Disorders of the trigeminal nerve | 6 | 2.78 (0.71 to 8.61) | 9 | 1.88 (0.60 to 5.07) | 15 | 2.16 (0.85 to 5.05) |

| Trigeminal neuralgia | 4 | 2.51 (0.46 to 9.20) | 7 | 2.28 (0.64 to 6.68) | 11 | 2.36 (0.83 to 5.99) |

| Facial nerve disorders | 17 | 2.48 (1.02 to 5.64) | 13 | 1.54 (0.58 to 3.73) | 30 | 1.96 (0.94 to 3.97) |

| Bell's palsy | 16 | 2.61 (1.05 to 6.01) | 13 | 1.73 (0.65 to 4.18) | 29 | 2.12 (1.00 to 4.32) |

| Disorders of other cranial nerves | 3 | 10.41 (1.39 to 43.56) | 0 | 3 | 1.97 (0.26 to 8.25) | |

| Nerve root and plexus disorders | 9 | 1.89 (0.60 to 5.09) | 12 | 2.08 (0.76 to 5.15) | 21 | 1.99 (0.87 to 4.31) |

| Disorders of the brachial plexus | 3 | 1.12 (0.15 to 4.70) | 5 | 2.30 (0.51 to 7.64) | 8 | 1.65 (0.50 to 4.62) |

| Mononeuritis of the upper limb and mononeuritis multiplex | 39 | 3.73 (1.87 to 7.21) | 55 | 3.17 (1.69 to 5.84) | 94 | 3.38 (1.93 to 5.85) |

| Carpal tunnel | 11 | 5.28 (1.85 to 13.41) | 30 | 3.77 (1.80 to 7.62) | 41 | 4.08 (2.07 to 7.84) |

| Ulnar nerve | 15 | 3.32 (1.31 to 7.76) | 11 | 2.09 (0.73 to 5.30) | 26 | 2.66 (1.23 to 5.51) |

| Radial nerve | 6 | 2.75 (0.70 to 8.52) | 8 | 3.92 (1.18 to 10.97) | 14 | 3.31 (1.28 to 7.88) |

| Mononeuritis of the lower limb | 6 | 1.14 (0.29 to 3.54) | 22 | 3.42 (1.51 to 7.32) | 28 | 2.39 (1.12 to 4.90) |

| Meralgia paresthetica | 2 | 5.51 (0.37 to 28.63) | 2 | 1.54 (0.10 to 8.02) | 4 | 2.41 (0.44 to 8.81) |

| Lateral poplitean nerve | 1 | 0.88 (0.00 to 7.10) | 5 | 8.03 (1.79 to 26.71) | 6 | 3.40 (0.87 to 10.54) |

| Plantar nerve | 1 | 1.78 (0.00 to 14.44) | 4 | 8.41 (1.55 to 30.76) | 5 | 4.82 (1.08 to 16.04) |

| All types | 80 | 2.69 (1.51 to 4.73) | 111 | 2.52 (1.47 to 4.30) | 191 | 2.59 (1.58 to 4.22) |

O, observed number of cases; SIR, standardised incidence ratio.

Bold face : 95% CI does not include 1.

Table 3 shows data for subtypes of nerve, nerve root and plexus disorders for both siblings. Most concordant SIRs were significant, and were highest for disorders of the trigeminal nerve (6.34) and mononeuritis of the upper (4.44) and lower (4.84) limbs. Only one sibling pair was diagnosed with concordant trigeminal neuralgia (SIR 6.54, 95% CI 0.41 to 43.04). For concordant Bell's palsy, the SIR was 3.94 (n = 14, 95% CI 1.52 to 9.37) and for concordant carpal tunnel syndrome, it was 9.22 (n = 16, 95% CI 3.72 to 21.22). Only two discordant associations were found: mononeuritis of the upper limb associated with both nerve root and plexus disorders (3.32) and mononeuritis of the lower limbs (3.07).

Table 3 Familial standardised incidence ratios for subtypes of nerve, nerve root and plexus disorders in siblings.

| Subtype in offspring | Disorders of the trigeminal nerve | Facial nerve disorders | Disorders of other cranial nerves | Nerve root and plexus disorders | Mononeuritis of the upper limb and mononeuritis multiplex | Mononeuritis of the lower limb | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| O | SIR (95% CI) | O | SIR (95% CI) | O | SIR (95% CI) | O | SIR (95% CI) | O | SIR (95% CI) | O | SIR (95% CI) | |

| Disorders of the trigeminal nerve | 4 | 6.34 (1.17to23.18) | 2 | 1.63 (0.11 to 8.48) | 0 | 1 | 1.09 (0.00 to 8.80) | 7 | 2.33 (0.65 to 6.83) | 1 | 1.02 (0.00 to –8.28) | |

| Facial nerve disorders | 2 | 1.75 (0.12 to 9.10) | 16 | 3.75 (1.51to8.63) | 0 | 2 | 1.08 (0.07 to 5.64) | 7 | 1.23 (0.34 to 3.60) | 3 | 1.56 (0.21 to 6.53) | |

| Bell's palsy | 2 | 1.99 (0.13 to 10.34) | 15 | 3.83 (1.51to8.96) | 0 | 2 | 1.22 (0.08 to 6.36) | 7 | 1.39 (0.39 to 4.08) | 3 | 1.75 (0.23 to 7.35) | |

| Disorders of other cranial nerves | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 3.22 (0.21 to 16.76) | 1 | 5.02 (0.00 to –40.70) | ||||

| Nerve root and plexus disorders | 1 | 1.18 (0.00 to –9.55) | 2 | 1.00 (0.07 to 5.18) | 0 | 2 | 1.42 (0.09 to 7.36) | 12 | 2.65 (0.96 to 6.58) | 4 | 2.70 (0.50 to 9.88) | |

| Mononeuritis of the upper limb and mononeuritis multiplex | 7 | 2.97 (0.83 to 8.69) | 7 | 1.41 (0.40 to 4.13) | 2 | 2.79 (0.19 to 14.52) | 12 | 3.23 (1.17to8.01) | 54 | 4.44 (2.36to8.21) | 12 | 3.07 (1.12to7.61) |

| Carpal tunnel | 1 | 1.14 (0.00 to 9.27) | 4 | 2.21 (0.41 to 8.09) | 1 | 3.81 (0.00 to 30.92) | 3 | 2.26 (0.30 to 9.45) | 27 | 6.18 (2.88to12.73) | 5 | 3.57 (0.80 to 11.86) |

| Mononeuritis of the lower limb | 1 | 1.07 (0.00 to 8.65) | 3 | 1.40 (0.19 to 5.85) | 1 | 3.58 (0.00 to 29.02) | 4 | 2.56 (0.47 to 9.37) | 11 | 2.15 (0.75 to 5.45) | 8 | 4.84 (1.46to13.56) |

| All types | 15 | 2.48 (0.98 to 5.79) | 30 | 2.01 (0.96 to 4.06) | 3 | 1.58 (0.21 to 6.62) | 21 | 2.18 (0.95 to 4.71) | 93 | 2.99 (1.71to5.18) | 29 | 2.86 (1.35to5.81) |

O, observed number of cases; SIR, standardised incidence ratio.

Boldface: 95% CI does not include 1.

Correlation of these diseases between spouses (specific subtype in one spouse compared with any nerve, nerve root and plexus disorders in the other) was analysed for 72 affected pairs (table 4). Disorders of the trigeminal nerves (2.07), specifically trigeminal neuralgia (2.21), were considerably increased for husbands whose wives were diagnosed with any nerve, nerve root and plexus disorders; however, wives were not at equally high risk. Correlation between spouses for mononeuritis of the upper limb was >2 and it was approximately equally as high for carpal tunnel syndrome as for the remaining disorders. For specific diagnoses in both spouses, trigeminal neuralgia showed an SIR of 3.96 (n = 3, 95% CI 0.75 to 11.73), Bell's palsy an SIR of 1.54 (n = 2, 95% CI 0.15 to 5.67) and carpal tunnel syndrome an SIR of 4.03 (n = 8, 95% CI 1.72 to 7.98). These SIRs are for husbands of affected wives; however, as the numbers of pairs were identical, the SIRs for wives were also almost identical. To investigate a possible environmental effect, the occupational titles of the patients diagnosed with carpal tunnel syndrome were retrieved, but none of the spouses shared occupations.

Table 4 Standardised Incidence Ratios for subtypes of nerve, nerve root and plexus disorders between spouses.

| Subtypes in spouses | Disorder in husbands | Disorders in wives | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| O | SIR (95% CI) | O | SIR (95% CI) | |

| Disorders of the trigeminal nerve | 12 | 2.07 (1.06to3.62) | 9 | 1.41 (0.64 to 2.70) |

| Trigeminal neuralgia | 11 | 2.21 (1.10to3.97) | 8 | 1.62 (0.69 to 3.21) |

| Facial nerve disorders | 11 | 1.19 (0.59 to 2.14) | 12 | 1.55 (0.80 to 2.72) |

| Bell's palsy | 10 | 1.23 (0.58 to 2.26) | 9 | 1.36 (0.62 to 2.59) |

| Disorders of other cranial nerves | 4 | 2.48 (0.64 to 6.41) | 1 | 0.92 (0.00 to 5.26) |

| Nerve root and plexus disorders | 5 | 1.00 (0.31 to 2.34) | 6 | 1.45 (0.52 to 3.18) |

| Mononeuritis of the upper limb and mononeuritis multiplex | 34 | 2.07 (1.43to2.89) | 36 | 2.04 (1.43to2.82) |

| Carpal tunnel | 14 | 2.05 (1.12to3.46) | 22 | 2.06 (1.29to3.13) |

| Mononeuritis of the lower limb | 6 | 1.40 (0.50 to 3.06) | 8 | 1.50 (0.64 to 2.97) |

| All types | 72 | 1.70 (1.33to2.14) | 72 | 1.70 (1.33to2.14) |

O, observed number of cases; SIR, standardised incidence ratio.

Boldface: 95% CI does not include 1.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic study on familial risks in nerve, nerve root and plexus disorders. The use of hospitalisations as an outcome may have advantages and disadvantages.14,17 Many of the diagnoses will not require hospitalisation and the rates would be lower than those seen in the general population. On the other hand, diagnostic accuracy was probably good overall because hospitalisation normally involved a diagnosis made by several physicians, including neurologists. An advantage of a nationwide, fully register‐based study is that selection biases are minimised and both the probands and the patients are medically diagnosed. Almost any alternative approach would require interviewing patients about similar diseases in their relatives, which has been shown to yield highly inaccurate data even for relatively well defined and life‐threatening diseases, such as cancer.18 A potential problem could be selective hospitalisation; when one sibling is hospitalised, other siblings may preferentially also seek care. Such a selection bias would be likely for conditions that do not invariably lead to hospitalisation, including many of the studied diseases in mild forms. To test for the likelihood of such bias, we calculated risks for spouses, who would be expected to show a higher level of environmental sharing than siblings for any adult‐onset diseases. We have previously estimated the potential for such a selection by comparing hospitalisation rates for migraine between spouses, and found no evidence supporting bias.14 Moreover, as this was a countrywide study, the diagnostic practices of single hospitals were unlikely to bias the results. However, for the studied diseases, correlations between spouses were observed, as discussed later. As the national Hospital Discharge Register has only been in operation since 1987, this study covered a time period of no longer than 15 years, partially contributing to the small numbers of cases for specific diagnostic groups. Overall, familial cases were rare, limiting the statistical power of the study. All family studies are prone to data on false paternity, which would bias results towards null.

The incidence of trigeminal neuralgia is given as 4.3 per 100 000 person‐years, with a female excess of 3:2.1 In our study, the hospitalisation rate in the 0–69‐year‐old population was 1.1 per 100 000, with a moderate female excess. Our lower incidence figures could reflect selection for hospitalisation or the truncated population, lacking elderly groups who have a high incidence (fig 1). The reported incidence for Bell's palsy has varied between studies from about 10 to 40 per 100 000 person‐years, equal in both sexes.3,17,19 Our study found a rate of 4 per 100 000 person‐years, equal for both sexes; however, again, part of this lower incidence would be explained by truncation of the population and lacking of the high‐risk population at ages ⩾70 years (fig 1). In the UK study, only 19% of the patients with Bell's palsy were referred to a hospital during the year after the initial onset of the disease; the hospitalisation rate in this UK study was almost exactly as ours, 4 per 100 00 person‐years.17 The incidence of carpal tunnel syndrome was found to be 88 per 100 000 for men and 193 per 100 000 for women in the UK General Practice Research Database.20 The crude rate in our study was much lower, 19 per 100 000 for men and 46 per 100 000 for women, but interestingly, the female excess was almost exactly that of the UK study. These data are consistent with the notion that our study data are lower than population morbidity, but hospitalisation rates may not bias sex‐specific rates. Thus, because of the various truncations, the hospitalisation rates should not be regarded as population incidence rates for all or any subtypes of these diseases. Hospitalisations are likely to be more preferential for severe symptoms and diseases, for which diagnostics require specialist consultation. Another explanation could be worse prognosis and preferential hospital referral in the familial cases. However, the truncations as such should not bias familial risks, the estimation of which was the novel aspect of this study.

What is already known

Nerve, nerve root and plexus disorders are common disorders, including Bell's palsy and carpal tunnel syndrome, with many types of known environmental causes.

Little is known about their possible familial clustering, which might indicate shared environmental causes or inheritable aetiology.

What this paper adds

Familial clustering between siblings was observed for all nerve, nerve root and plexus disorders and for specific subtypes.

Some concordance was also observed for spouses, probably indicating environmental sharing.

However, as the risks between siblings were higher than those between spouses, an inheritable contribution is probable.

The overall familial risk was 2.59, equal for men and women. Facial nerve disorders and mononeuritis of the limbs showed familial risk when the co‐siblings presented with any nerve, nerve root and plexus disorder (table 2). Limb mononeuritis did not include radiculopathies because these were classified under nerve root and plexus disorders, which showed no evidence on familial clustering. For men, even disorders of other cranial roots were significant (SIR 10.41). When specific subtypes were compared in both siblings, disorders of the trigeminal nerve (6.34), Bell's palsy (3.94) and carpal tunnel syndrome (9.22) showed increased risk. Only mononeuritis of the upper limbs was associated with discordant subtypes, nerve root and plexus disorders (3.32) and mononeuritis of the lower limb (3.07); this observation may imply shared disease mechanisms or aetiology. Herpes simplex infection is considered the major cause of trigeminal neuralgia and Bell's palsy, and it is thus conceivable that siblings share infection and the viral source of the disease. The correlation between spouses for trigeminal neuralgia supported this possibility, at least as a partial explanation. For Bell's palsy, no large correlation between spouses was observed, and the familial risks may reflect inheritable susceptibility to viral infection or other genetic causes. For carpal tunnel syndrome, the familial risk (9.22) exceeded correlation between spouses (4.03), and environmental factors may not fully explain the sibling risk. Known familial clusters often involve bilateral disease, and it has been suggested that carpal tunnel diameters may be inheritable and thus contribute to disease proneness.13

The results of this study should encourage an eetiological search for the causes of the familial aggregation. Although our data cannot distinguish between the contributions of inheritability or shared environmental factors, or their interactions, to the observed familial aggregation, they clearly show that familial clustering is present. Molecular genetic techniques have been successful in dissecting many monogenic neurological disease,21 but nerve, nerve root and plexus disorders seem to be multifactorial, which may require a careful selection of the population with disease for study.

Abbreviations

ICD - International Classification of Diseases

SIR - standardised incidence ratio

Footnotes

Funding: This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (Grant Number. R01‐H271084‐1), the Swedish Research Council (Grant Number. K2004‐21X‐11651‐09A to Dr JS and K2005‐27X‐15428‐01A to Dr KS), and the Swedish Council for Working Life and Social Research (Grant Number. 2001–2373).

Competing interests: None declared.

This study was approved by the ethics committee at Karolinska Institute, Stockholm.

References

- 1.Ropper A, Brown R.Adams and Victor's principles of neurology. 8th edn. New York: McGraw‐Hill, 2005

- 2.Hentschel K, Capobianco D J, Dodick D W. Facial pain. Neurologist 200511244–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gilden D. Bell's palsy. N Engl J Med 20043511323–1331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rempel D M, Diao E. Entrapment neuropathies: pathophysiology and pathogenesis. J Electromyogr Kinesiol 20041471–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Atroshi I, Gummesson C, Johnsson R.et al Prevalence of carpal tunnel syndrome in a general population. JAMA 1999282153–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bland J D, Rudolfer S M. Clinical surveillance of carpal tunnel syndrome in two areas of the United Kingdom, 1991–2001. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2003741674–1679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burton P, Tobin M, Hopper J. Key concepts in genetic epidemiology. Lancet 2005366941–951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meuleman J, Timmerman V, Van Broeckhoven C.et al Hereditary neuralgic amyotrophy. Neurogenetics 20013115–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kuhlenbaumer G, Hannibal M C, Nelis E.et al Mutations in SEPT9 cause hereditary neuralgic amyotrophy. Nat Genet 2005371044–1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smyth P, Greenough G, Stommel E. Familial trigeminal neuralgia: case reports and review of the literature. Headache 200343910–915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kondev L, Bhadelia R A, Douglass L M. Familial congenital facial palsy. Pediatr Neurol 200430367–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zaidi F H, Gregory‐Evans K, Acheson J F.et al Familial Bell's palsy in females: a phenotype with a predilection for eyelids and lacrimal gland. Orbit 200524121–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alford J W, Weiss A P, Akelman E. The familial incidence of carpal tunnel syndrome in patients with unilateral and bilateral disease. Am J Orthop 200433397–400. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hemminki K, Li X, Johansson S.et al Familial risks for migraine and other headaches among siblings based on hospitalisations in Sweden. Neurogenetics 20056217–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hemminki K, Li X, Johansson S.et al Familial risks of aortic aneurysms among siblings in a nation wide Swedish study. Genet Med 2006843–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hemminki K, Vaittinen P, Dong C.et al Sibling risks in cancer: clues to recessive or X‐linked genes? Br J Cancer 200184388–391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rowlands S, Hooper R, Hughes R.et al The epidemiology and treatment of Bell's palsy in the UK. Eur J Neurol 2002963–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Murff H J, Spigel D R, Syngal S. Does this patient have a family history of cancer? An evidence‐based analysis of the accuracy of family cancer history. JAMA 20042921480–1489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Campbell K E, Brundage J F. Effects of climate, latitude, and season on the incidence of Bell's palsy in the US Armed Forces, October 1997 to September 1999. Am J Epidemiol 200215632–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Latinovic R, Gulliford M C, Hughes R A. Incidence of common compressive neuropathies in primary care. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 200677263–265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bertram L, Tanzi R E. The genetic epidemiology of neurodegenerative disease. J Clin Invest 20051151449–1457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]